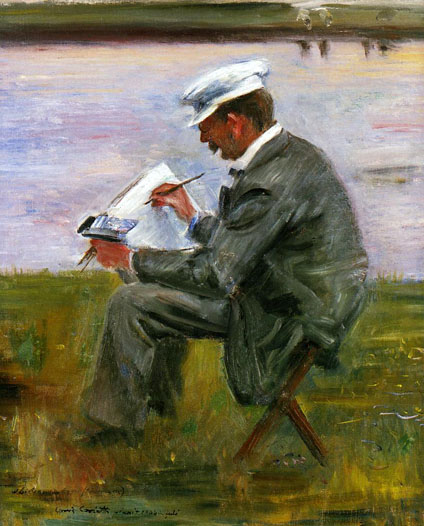

Self Portrait: 1887-88

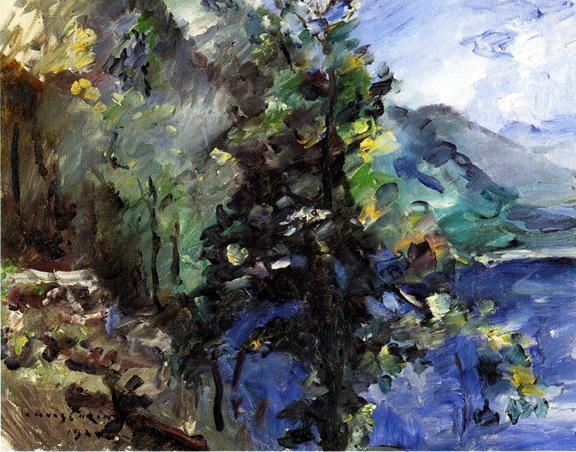

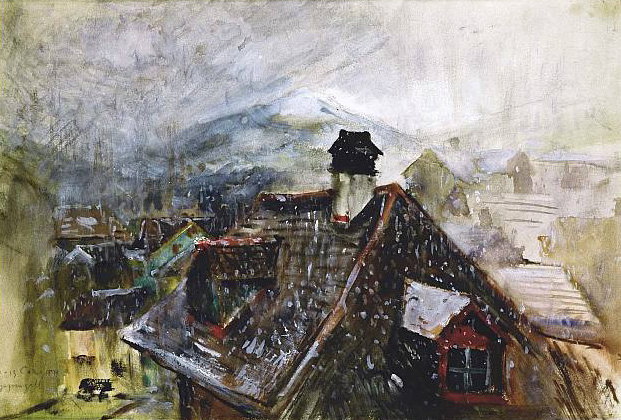

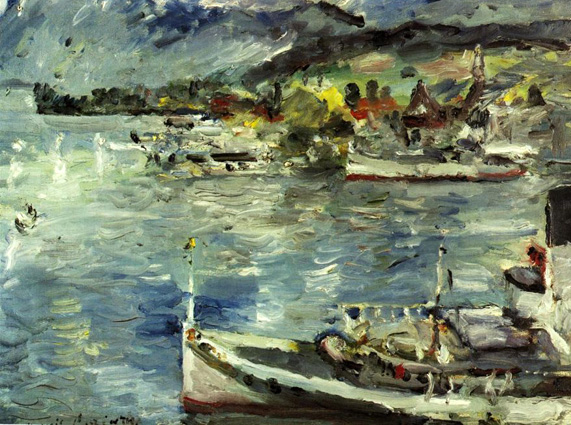

Walchensee: 1920

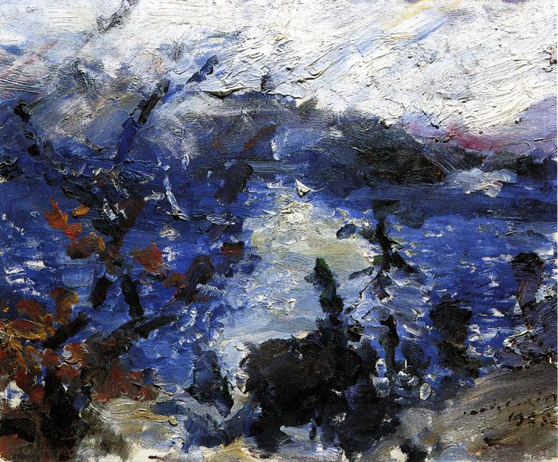

The Walchensee in the Moonlight: 1920

The Walchensee in Winter: 1923

The Walchensee on Saint John's Eve: 1920

The Walchensee with a Larch Tree: 1921

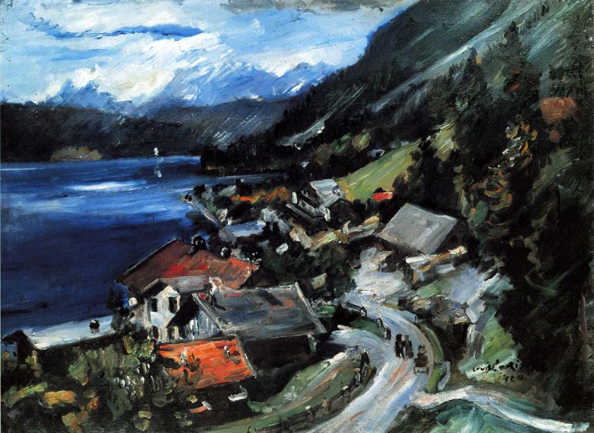

The Walchensee with Mountain Range and Shore: 1925

The Walchensee with the Slope of the Jochberg: 1924

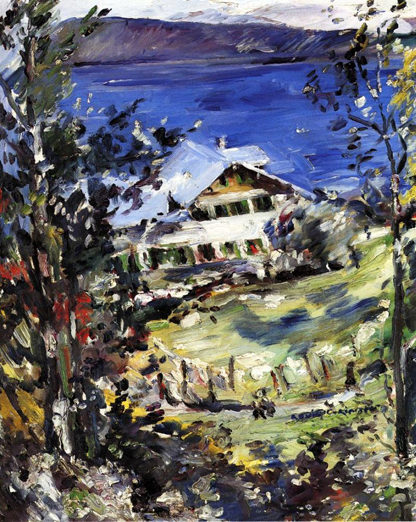

The Walchensee, Country House with Washing on the Line: 1923

The Walchensee-Mountains Wreathed in Cloud: 1925

The Walchensee, New Snow: 1922

The Walchensee, on the Terrace: 1922

The Walchensee, Serpentine: 1920

The Walchensee, Silberweg: 1923

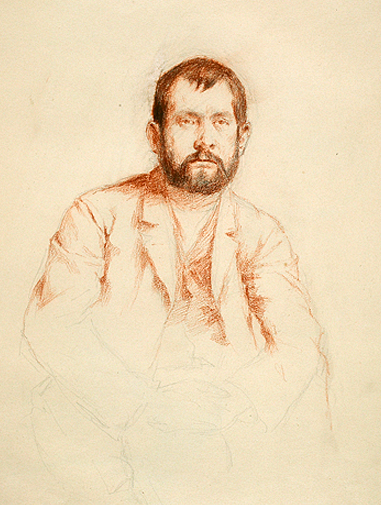

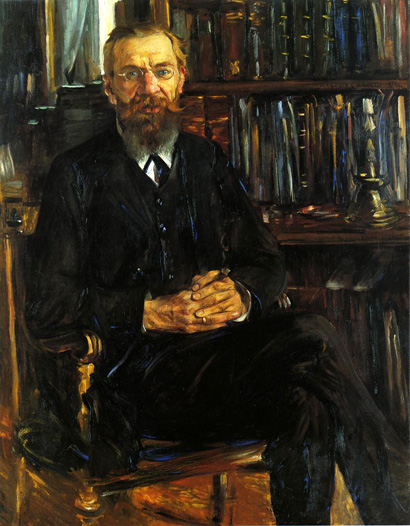

Self Portrait with Beard: 1886

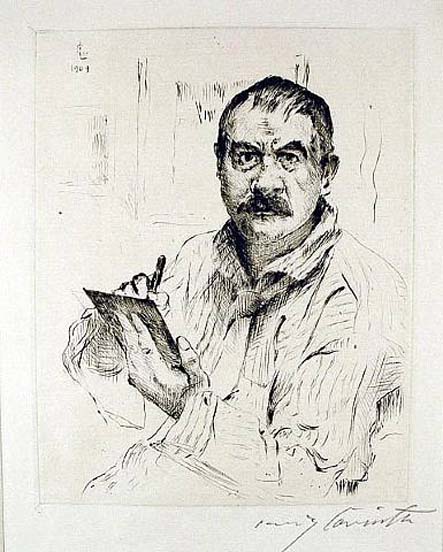

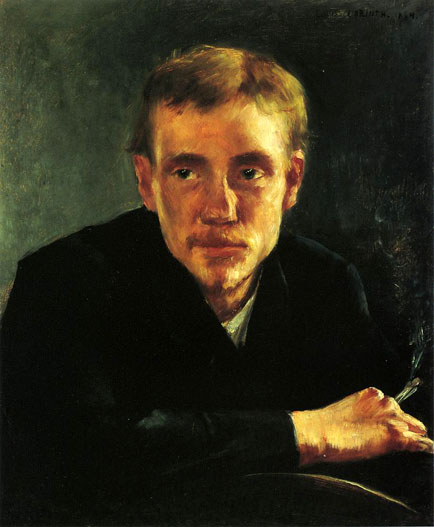

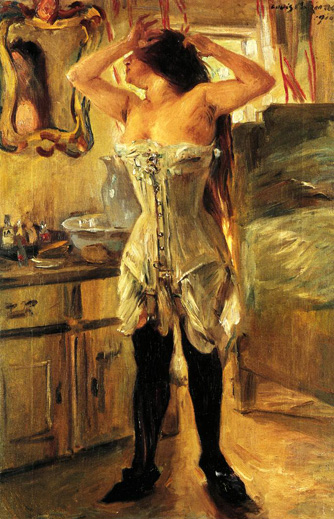

Self Portrait: 1887-88

Lovis Corinth's disciplined brushwork is seen in the 'Self-Portrait' from the winter of 1887-88. This painting projects the artist's physical presence with "startling" immediacy. Although this effect results partly from the quizzical, apprehensive gaze, it is reinforced by the tangible life-size head emerging from the undifferentiated pictorial ground.

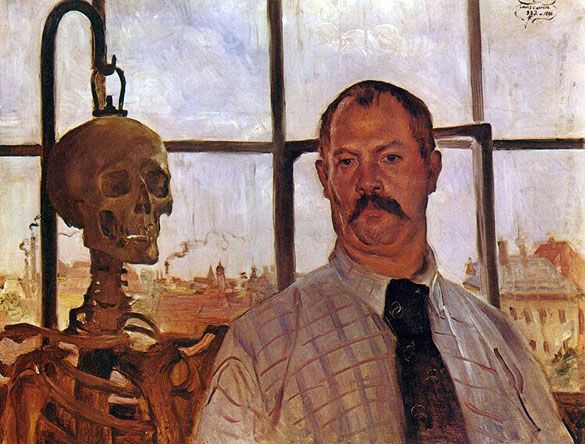

Self Portrait with Skeleton: 1896

Self Portrait without Collar: 1901

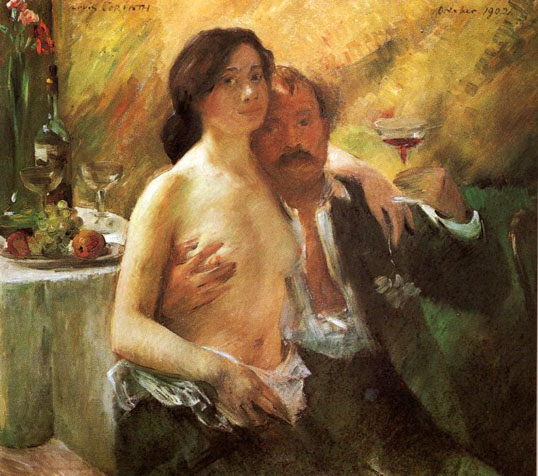

Self Portrait with his Wife and a Glass of Champagne: 1902

Charlotte Berend's expanded role in Corinth's life is documented by several paintings from 1902 for which she posed in the nude. They include the large double portrait painted in October after the lovers' return from Bavaria. An immense gulf separates this painting from the preceding double portrait in which Corinth, assured in his professional calling, had depicted himself at work in the company of a young model. Primacy of place now belongs to Charlotte Berend. Her body, naked to just below the waist, is fully illuminated, and she engages the viewer's attention with her open gaze. She holds a flower in her left hand, again most likely in symbolic allusion to her youth. Corinth himself looks younger and trimmer than in any of the self-portraits from the 1890's. Supporting Charlotte on his knee, he raises a glass in celebration of their love. According to Charlotte Berend, the idea for the double portrait originated with Corinth himself, and the execution of the painting proceeded as swiftly as the energetic brushstrokes suggest:

As he began to paint, it seemed to me that I had never known him like this. He rejoiced as he worked . . . and shouted: "How happy this makes me. . . . Just look, the picture is painting itself of its own accord. Come, let's take a short break! I'm going to have some wine, and you have some too.". . . He laughed. "Cheers, my Petermannchen, and now back to work!

Self Portrait with Model: 1903

In June 1903, about three months after his marriage to Charlotte Berend, Corinth returned to the subject of the double portrait in a considerably modified form. Although Charlotte again occupies the frontal plane of the picture, the painter dominates it, showing himself with the tools of his profession recording the image he sees before him. There is no longer any hint of apprehension about Charlotte's youth, and the intoxication of courtship has given way to a new self-assurance. Corinth has clearly regained control of his emotional life. He confronts himself boldly; Charlotte, her back toward the viewer, stands close to the painter, protected by his arms, but also shielding him, her gesture at once suppliant and supportive. The emotional equilibrium the couple has achieved is echoed in the balanced pictorial structure. The two standing figures emphasize the central vertical axis of the composition; the painter's hands accentuate the corresponding horizontal division. A few years later Corinth reproduced a photograph of this painting in his teaching manual as an example of how to distribute the structural elements in a pictorial field so as to achieve a well-thought-out, balanced composition.

Self Portrait with a Glass: 1907

Corinth's skeptical expression as he gazes at his mirror image is puzzling. He seems to be contemplating an illusion he knew he could not represent. The mood of uncertainty is further emphasized by the word ipse inscribed on the painting from 1907. In the prototypical roles of these self-portraits that could give his character a generalized dimension, Corinth continued to celebrate the Nietzsche ideal of the natural and instinctual individual who-unhampered by decorum-seeks regeneration in spontaneous actions.

Self-Portrait: 1909

The Victor: 1910

In the double portrait from 1910 Corinth places his hand on the shoulder of Charlotte Berend as if taking possession of a prize after a victorious battle. Charlotte Berend, in turn, revels in the strength of the conquering hero, nestling seductively against the gleaming armor. In the self-portrait from 1911 and the related bust-length self-portrait from the same year Corinth's expression conveys unyielding determination, the readiness to meet any challenge.

Both personal aspirations and Nietzsche's notions of the warlike Übermensch who sets his own moral code underlie the conception of these paintings. Corinth's almost Darwinian view of life and his belief in the survival of the fittest are suggested by a comment in his autobiography on the faculty intrigues at the Königsberg Academy that eventually led to the resignation of his teacher Otto Edmund Günther:

Since the battle for existence forces the artist to do his best, the competition is extreme. It does not matter whether his colleagues, even his best friends, perish all around him, as long as he wins out as the strongest. As long as the strength of the victor remains decisive in this battle, nobody needs to be pitied, for it is the fate of the weak to succumb to the strong.

Self Portrait as Standard Bearer: 1911

Self Portrait in a Black Hat: 1911

Self Portrait in a Tyrolean Hat: 1913

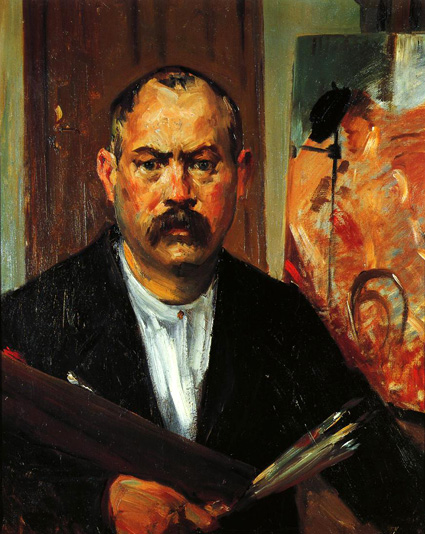

Self Portrait in the Studio: 1914

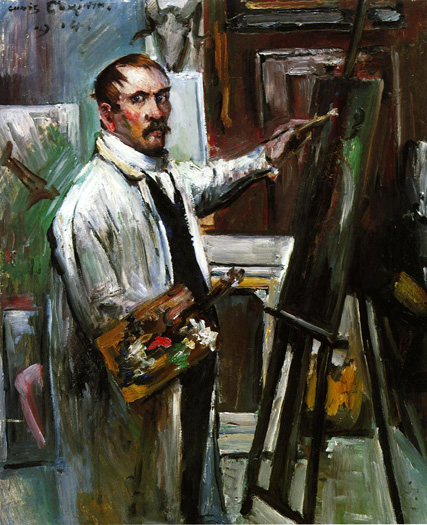

Self-Portrait at his Easel: 1914

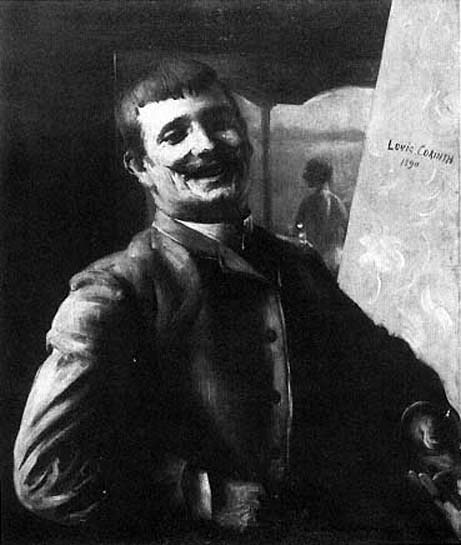

"An artist paints himself in the act of painting himself. He gazes at the person who interests him most, doing what he enjoys doing most. Nothing in art is more self-obsessed than a self-portrait of an artist at work. This is the German painter, Lovis Corinth. He is in his studio in the year 1914. Corinth is 56…"

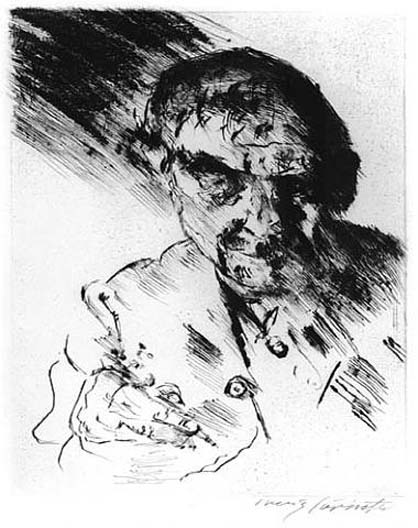

Self Portrait With Armor

Like Kathe Kollwitz, his contemporary in Germany, Corinth experimented with printmaking and could render powerful images in black and white as well as color. His 'Self Portrait With Armor' shows the artist wearing a suit of armor he kept in his studio as a prop. Corinth wore his passionate German nationalistic feelings like a suit of armor as well. He joined the Berlin Secession in 1901 and became its president in 1915, serving until his death in 1925. Upon becoming president, many of the members left the Secession, disagreeing with Corinth's nationalism and the direction he wished to take the organization. Even in the midst of the horrors of World War I, Corinth continued to stand beside his homeland.

Self-Portrait with Hat and Coat: 1915

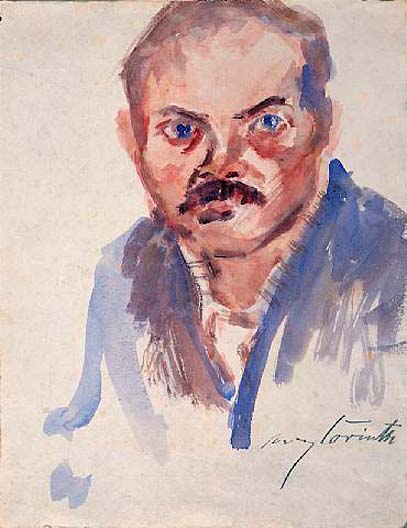

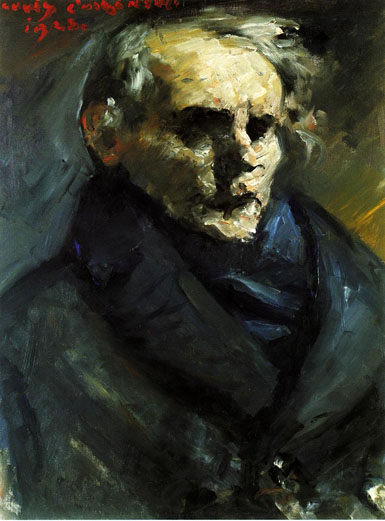

After suffering a near-fatal stroke in 1911, Corinth often turned to painting his own image to reveal insight into his emotions. This candid, expressive painting is one of his finest self-portraits from the last decade of his life. His powerful, spontaneous style influenced the development of modernist painting in Germany. From 1915 to 1925, he served as president of the Berlin Secession, a group formed in opposition against state-sponsored art and which organized its own independent exhibitions.

Self-Portrait: 1916

Self Portrait in a White Smock: 1918

Self-Portrait: 1918

Self Portrait in Fur Cap: 1918

Self-Portrait: 1919

Self Portrait at the Easel: 1919

Self Portrait at the Easel: 1922

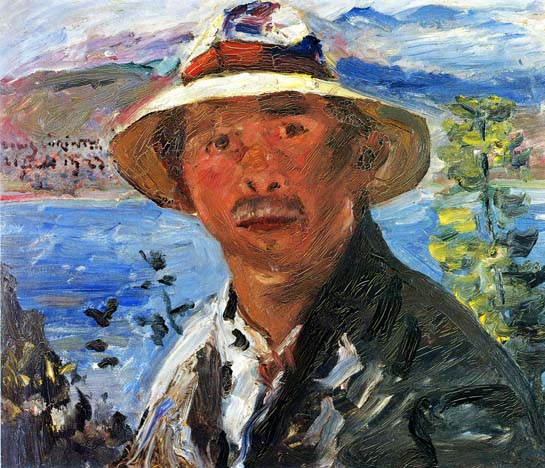

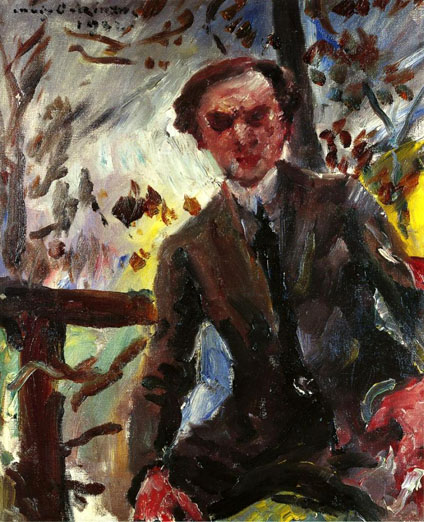

Self Portrait with Straw Hat: 1923

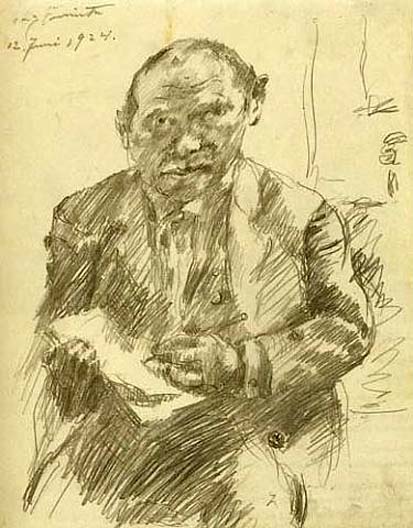

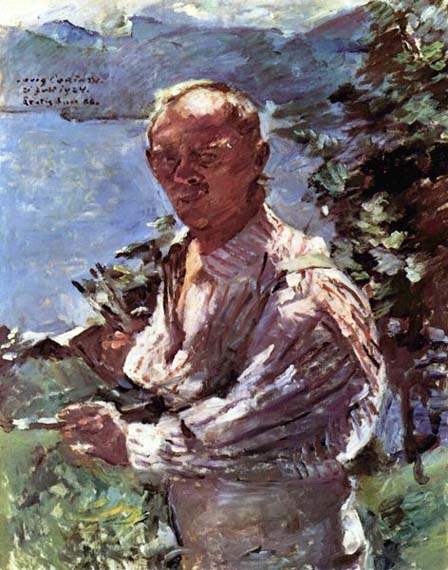

Self-Portrait: 1924

Self-Portrait: 1924

Self-Portrait: 1925

Self-Portrait: 1925

(Last Self Portrait)

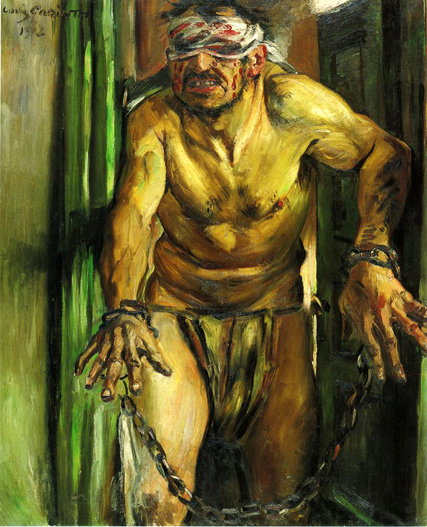

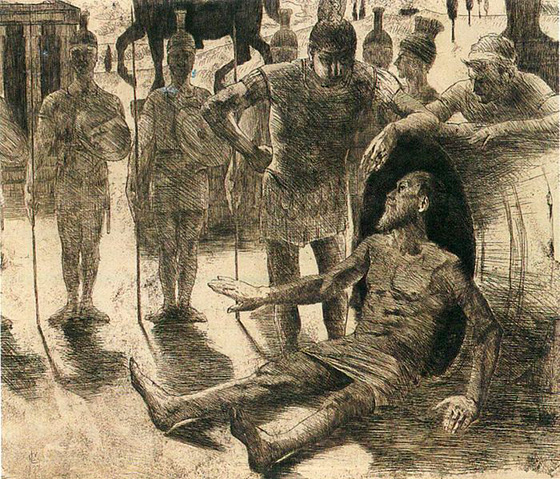

The Blinded Samson: 1912

Lovis Corinth, German Impressionist and later Expressionist (although he would have denied either label), was born on July 21, 1858. Corinth's apparent turn in style coincided with the stroke he suffered in 1911 that rendered his left side partially paralyzed. The Impressionist style he displayed with his natural left handedness soon became tortured Expressionism as he relearned how to draw and paint with his right hand. Corinth painted Samson Blinded in 1912, just a year after his paralysis. The portrait of the debilitated Biblical strongman may be a portrait of Corinth's own emotional state as he came to grips with the reality that the remarkable draftsmanship of his youth was gone.

Self Portrait: 1924

Self Portrait: 1924

(An Alternative, Maybe, but I am not sure)

Various Works of Lovis Corinth

(Potraits, Mythological & Religious Themes, and Tatesful Nudes)

Any of you who have spent much time on my Art Pages, I hope, have realized that I have no claim to expertise in the area of art. Yet, my appreciation and joy of art in all it genres never ceases to amaze me how fulfilling it is to my emotional and spiritual psyche. When I look at Corinth's work as a whole, I see an 'Impressionist' but who am I to judge when I do not see or fully understand this synthesis between impressionism and expressionism. Time has the ability to bring understanding so we will have to see how open my mind is to such an epiphany.

Senex Magister

Admiral Von Tirpitz: 1917

Lovis Corinth wanted to paint the former secretary of state of the Imperial Navy Department because he considered him to be one of "the greatest of the time". A few days previously, Germany had recommenced unlimited submarine warfare after a break of two years. From this point, war ships and trading vessels could be torpedoed without warning. This form of warfare had been broken off in 1915, because the destruction of the "Lusitania" had been responsible for the death of 1200 people. Despite this death toll, Tirpitz had continued to support the continuation of unlimited submarine warfare.

Appenzell

Ariadne auf Naxos: 1913

Synopsis

Ariadne auf Naxos

Composer: Richard Strauss

PROLOGUE: In the salon of "the richest man in Vienna," preparations are in progress for a new opera seria based on the Ariadne legend, with which the master of the house will divert his guests after a sumptuous dinner. The Music Master accosts the pompous Major-domo, having heard that a foolish comedy is to follow his pupil's opera, and warns that the Composer will never tolerate such an arrangement. The Major-domo is unimpressed. No sooner have they gone than the young Composer comes in for a final rehearsal, but an impudent lackey informs him that the violins are playing at dinner. A sudden inspiration brings him a new melody, but the Tenor is too busy arguing with the Wigmaker to listen to it. Zerbinetta, pert leader of some comedians, emerges from her dressing room with an officer just as the Prima Donna comes out asking the Music Master to send for "the Count." At first attracted to Zerbinetta, the Composer is outraged when he learns she and her troupe are to share the bill with his masterpiece. Zerbinetta and the Prima Donna lock horns while dissension spreads. As the commotion reaches its height, the Major-domo returns with a flourish to announce that because of limited time, the opera and the comedy are to be played simultaneously, succeeded by a fireworks display. At first dumbstruck, the artists try to collect themselves and plan: the Dancing Master extracts musical cuts from the despairing Composer, with the lead singers each urging that the other's parts be abridged, while the comedians are given a briefing on the opera's plot. Ariadne, they are told, after being abandoned by Theseus, has come to Naxos alone to wait for death. No, says Zerbinetta - she only wants a new lover. The comedienne decides her troupe will portray a band of travelers trapped on the island by chance. Bidding the Composer take heart, she assures him that she too longs for a lasting romance, like Ariadne, but as his interest in the actress grows, she suddenly dashes off to join her colleagues. Now the Prima Donna threatens not to go on, but the Music Master promises her a triumph, and the heartened Composer greets his teacher with a paean to music. At the last minute he catches sight of the comics in full cry and runs out in horror.

THE OPERA: Ariadne is seen first at her grotto, watched over by three nymphs - Najade, Dryade and Echo - who sympathize with her grief. Enter the buffoons, who attempt to cheer her up - to no avail. As if in a trance, Ariadne resolves to await Hermes, messenger of death; he will take her to another world, undefiled - the realm of death. When the comedians still fail to divert Ariadne, Zerbinetta addresses her directly. She describes the frailty of women, the willfulness of men and the human compulsion to change an old love for a new. Insulted, Ariadne retires to her cave. When Zerbinetta concludes her address, her cronies leap on for more sport. Harlekin tries to embrace her while Scaramuccio, Truffaldin and Brighella compete for her attention, but it is Harlekin to whom she at last surrenders. The nymphs return, heralding the approach of a ship. It bears the young god Bacchus, who has escaped the enchantress Circe for Ariadne. Bacchus is heard in the distance, and Ariadne prepares to greet her visitor - surely death at last. When he appears, she thinks him Theseus come back to her, but he majestically proclaims his godhood. Entranced by her, he claims he would sooner see the stars banish than give her up. Reconciled to a new, exalted existence, Ariadne joins Bacchus in an ascent to the heavens as Zerbinetta sneaks in to have the last word: "When a new god comes along, we're dumbstruck."

Armor in the Studio: 1918

At the Muritzsee: 1915

At the Mirror:1912

Autumn Flowers: 1895-96

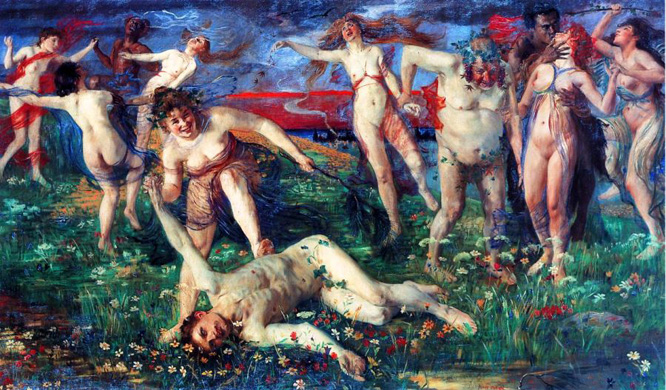

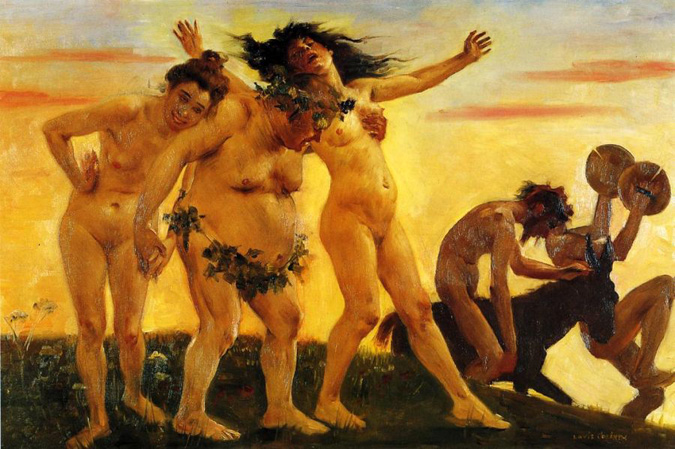

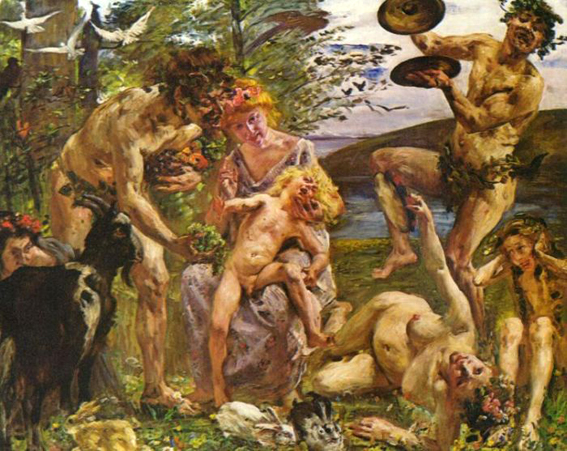

Bacchanal: 1896

Bacchanalia

The Bacchanalia were wild and mystic festivals of the Roman god Bacchus (or Dionysus). It has since come to describe any form of drunken revelry.

The bacchanalia were originally held in secret and only attended by women. The festivals occurred in the grove of Simila near the Aventine Hill on March 16 and March 17. Later, admission to the rites was extended to men, and celebrations took place five times a month. According to Livy, the extension happened in an era when the leader of the Bacchus cult was Paculla Annia - though it is now believed that some men had participated before that.

Livy informs us that the rapid spread of the cult, which he claims indulged in all kinds of crimes and political conspiracies at its nocturnal meetings, led in 186 BC to a decree of the Senate - the so-called Senatus consultum de Bacchanalibus, inscribed on a bronze tablet discovered in Apulia in Southern Italy (1640), now at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna - by which the Bacchanalia were prohibited throughout all Italy except in certain special cases which must be approved specifically by the Senate. In spite of the severe punishment inflicted on those found in violation of this decree (Livy claims there were more executions than imprisonment), the Bacchanalia survived in Southern Italy long past the repression.

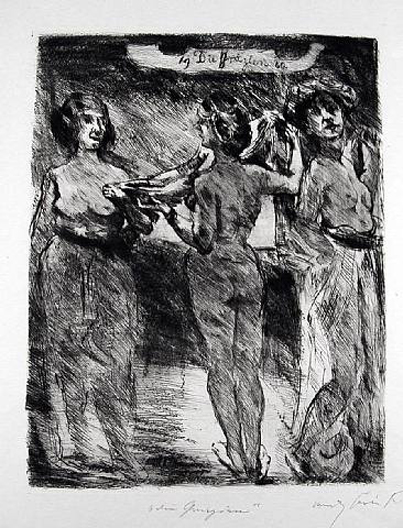

Baccants Returning Home: 1898

Maenads in Greek Mythology

Maeands (also known as Bacchantes, Bacchae, or Thyiades) played an important role in Greek mythology, literature, and art. These women worshipped the Greek god Dionysos, and, along with the notorious satyrs, formed part of the god's entourage. Indeed, Maenads frequently appear together with the frenzied deity of wine in both myth and art, where they are depicted holding Dionysian symbols such as the thyrsos, ivy, or grapes, and often shown wearing panther or fawn skins.

One of our best ancient sources for the story of Dionysos and his Maenad followers is found in the Bacchae of Euripides. In this play, the power and destructive capacity of Dionysos are emphasized. This deadly aspect of the god is conveyed primarily through the women who are drawn into his mysterious realm. These women (who, as the title indicates, are called Bacchae or Bacchantes) celebrate Dionysos by abandoning themselves to the wild, liberating energy of nature. Bacchantes, when in the trance of the deity, leave behind home and family, and haunt the forests and mountains, their roles as wives, mothers, and sisters temporarily forgotten.

The Internet Classics Archive | The Bacchantes by Euripides

Bacchantenpaar: 1908

Building under Construction in Monte Carlo: 1914

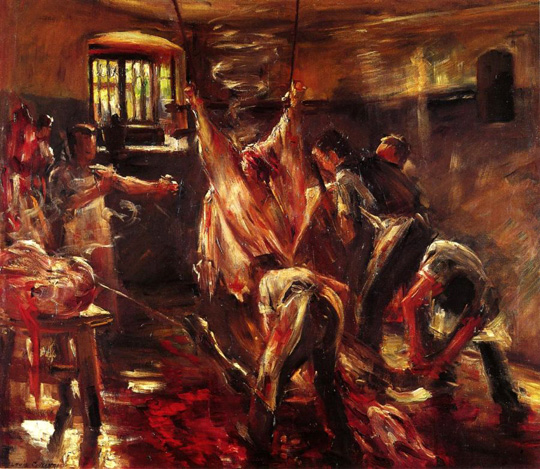

Butcher Shop: 1897

The extensive iconographic range of Corinth's works from the 1890's is a constant source of frustration to anyone seeking to bring order to the painter's varied output. Indeed, in 1897 he achieved a new level of competence in subjects that had claimed his attention previously: the light-filled interior and the portrait in the open air. In the butcher's store interior, painted in the small town of Schäftlarn in the Isar Valley, he subordinated the visceral conception of the slaughterhouse scene from 1892 to a more controlled structural logic in keeping with the less aggressive character of the subject. The vaults of the setting divide the pictorial field vertically into equal halves; the resulting equilibrium is subtly modified by the scaffolding of the meat racks. The simple ground, painted in relatively unified shades of red and green, provides an effective foil for the multicolored cuts of meat displayed on the counter and suspended from hooks above it. They derive their gleaming texture from the fatty gloss of the paint itself, applied in deft strokes of red and pink shot through with specks of white and purple. Corinth's painting has an expressive anecdotal content that ultimately allies it to the small slaughterhouse scene of 1892. The butcher's apprentice provokes the viewer's sensibilities by presenting a large dish piled high with pieces of freshly cut meat, his expression of smug self-satisfaction a mocking reminder of the grisly process just completed.

In the Slaughter House: 1893

Berta Heck in a Boat

In the portrait of Berta Heck, the sister of Max Halbe's wife, Corinth achieved a similar unity of structural logic and expressive content. The motif of the young woman seated in a boat, with a male companion just visible behind her, recalls similar paintings by the French Impressionists, in particular Manet's Boating (1874; Metropolitan Museum of Art), although it is impossible to say whether Corinth at this point actually knew these pictures. Having set up his canvas at the back of the boat, he apparently executed the painting from start to finish out of doors. But in contrast to the psychologically neutral approach of painters like Manet and Monet, Corinth was clearly unwilling to sacrifice the facial features of the model to the evanescent, form-dissolving effects of light. The brushstrokes, applied broadly to the lake and the distant shoreline and rapidly in the blouse and hat, become more differentiated in the young woman's face, making it both the structural and psychological focus of the composition. Averting her gaze, Berta Heck is absorbed in her innermost thoughts. The simple pictorial structure, dominated by three broad horizontal bands that divide the background, reinforces the picture's mood of quiet reverie. This sentiment is the result not only of considerable artistic growth but presumably also of a harmony between painter and model that prompted Corinth's empathy, allowing him to rise above a mere description of the sitter.

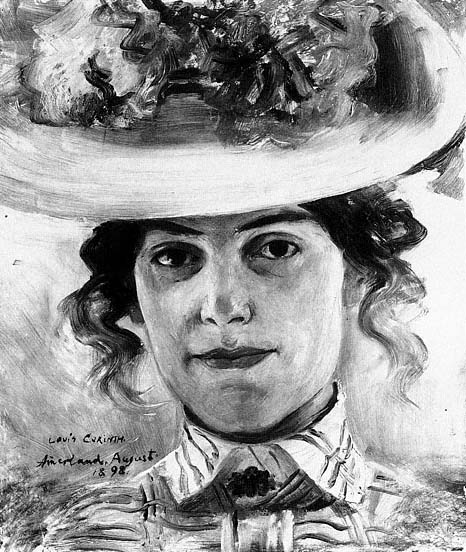

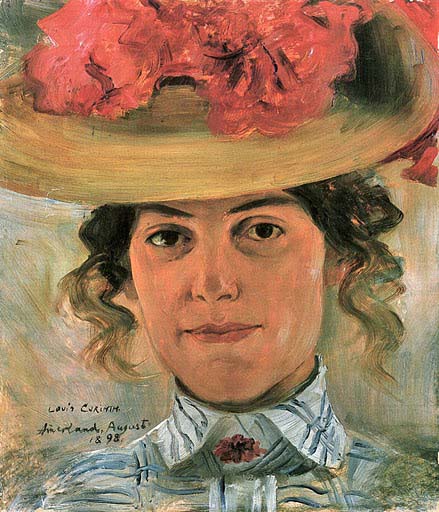

Portrait of Luise Halbe in a Straw Hat: 1898

In a similar way only considerable mutual trust can have made possible a portrait such as the one Corinth painted of Bertha Heck's sister, Luise Halbe, the following year.

Women's Half Portrait with Straw Hat

(Luise Halbe)

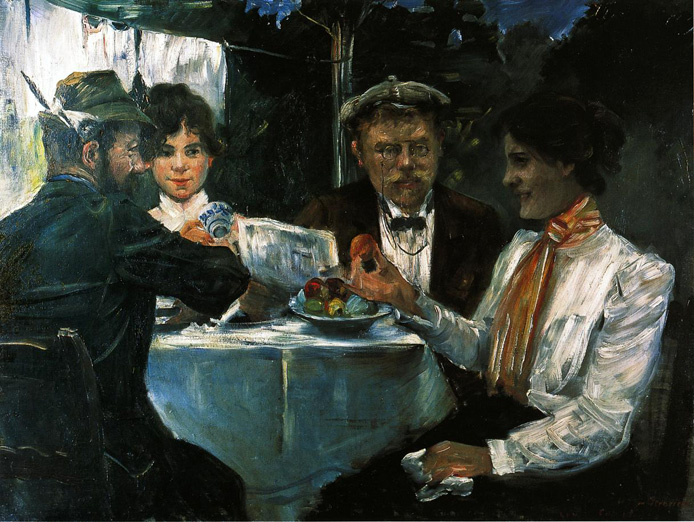

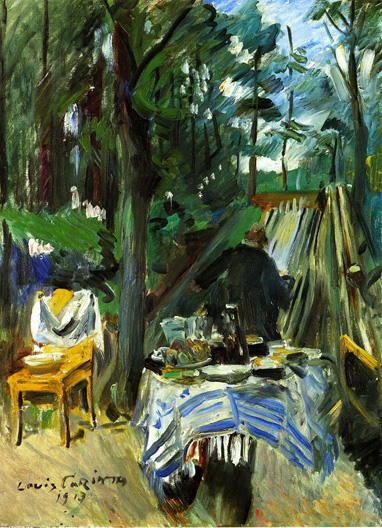

In Max Halbe's Garden: 1899

Cain: 1917

The right-handed, post-stroke Corinth began to paint in a highly Expressionist style. Although almost an entire generation older than most other Expressionist artists in Germany, especially the artists of Der Blaue Reiter and Die Brücke, Corinth felt compelled to play the younger man's game of angst and outrage. Corinth's Cain (from 1917) strikingly depicts the pain and the defiance of the Biblical character. Painted in the midst of Germany's involvement in World War I, it may also serve as a symbol of Germany's own fratricidal guilt in ginning up the war fever that soon consumed all of Europe in the flames. Corinth watched an entire generation of young men, including many of the fine young Expressionist painters, die in the war. Already manic-depressive, Corinth's natural pessimism grew even deeper during the war years.

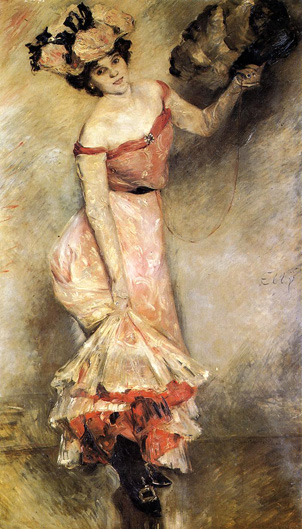

Carmencita: 1924

"The painting was done after a jolly evening. The party at the Secession was called 'A Southern Night'. I had gone as a Spanish woman", writes Charlotte Berend-Corinth shortly after her husband's death. Painted in 1924, shortly before he died, the almost life-size Carmencita concludes the long series of some eighty portraits that Corinth made of his wife, who was twenty-three years his junior. More important to him than the figure is the quick and vigorous application of the paint, pushed almost to the point of making the subject unrecognizable. Here, painting becomes its own subject. The viewer must see "into" the painting before gradually recognizing details like the headdress, the fan and the chandelier in the background. In his textbook on painting of 1907, Corinth points to the importance of "squinting", which he compares to an out-of-focus camera and which permits one to perceive the figure as the main event and its surroundings as soft masses of color. Together with Max Liebermann and Max Slevogt, Corinth is one of the most influential exponents of German Impressionism, whose idiosyncratic practice of modeling in shades of black and grey characterizes the Carmencita.

Cat's Breakfast:1913

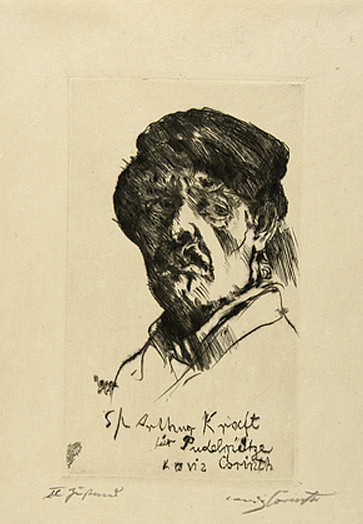

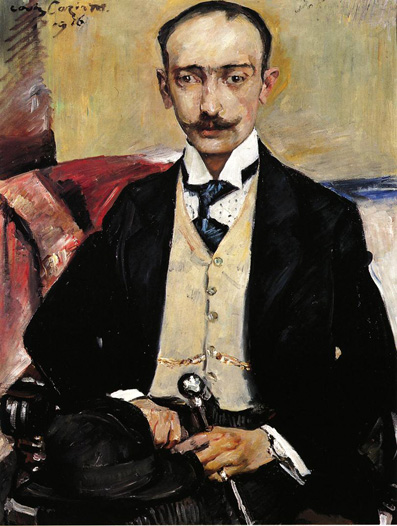

Cesare Borgia (Arthur Kraft): 1914

_1914.jpg)

Cowshed: 1912

Crucified Thief: 1883

Another of his paintings is Crucified Thief, a painting he produced in 1883. This is a very strong image of the human body. Corinth clearly was an artist who knew how to draw and paint, and to do so beautifully. He also did anatomical drawings with brilliant clarity. At the same time, though his work was technically brilliant, it did seem that he was doing it again and again and again.

The Conspiracy: 1884

Corinth painted 'The Conspiracy' in 1884, emphasizing the descriptive and expressive function of the light that enters the dusky room through cracks in the shutter. The painting is highly ambitious not only in scale but also in Corinth's mastery of the pictorial space. Unlike the figures in Corinth's earlier portraits, the three men in the 1884 painting occupy a defined interior. Corinth's sense that one of his chief tasks in painting the picture was to articulate the interior space is evident from the calculated means he used to achieve this goal: reinforced by the repoussoir (i.e. a figure or object in the extreme foreground: used as a contrast and to increase the illusion of depth) of the large dog in the foreground, the four chairs, standing at right angles to each other, serve as the primary space-defining elements. Apparently Corinth invested the painting with a specific anecdotal content only after completing it. In short, like the 'Crucified Thief' of the preceding year,' The Conspiracy' , originally entitled 'The Black Plot', is still a typical student work. Nonetheless, Corinth was sufficiently satisfied with it to send it to London for exhibition.

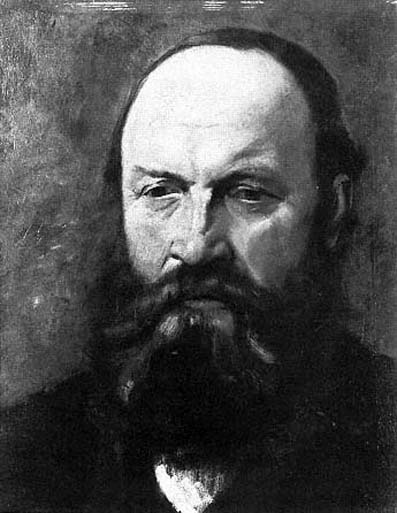

Portrait of the Painter: 1884

Paul Eugène Gorge

In the portrait of Paul Eugène Gorge Corinth juxtaposed the grayish blue of the background with the sitter's ruddy complexion and blond hair. The paint has been applied in fluid strokes, accentuating the contrasts of light and shade engendered by a strong source of illumination just outside the picture to the sitter's left. Gorge's posture is casual and relaxed. His gentle gaze gives credence to the purity of character Corinth admired in him, which helped to forge a lasting friendship between the two men.

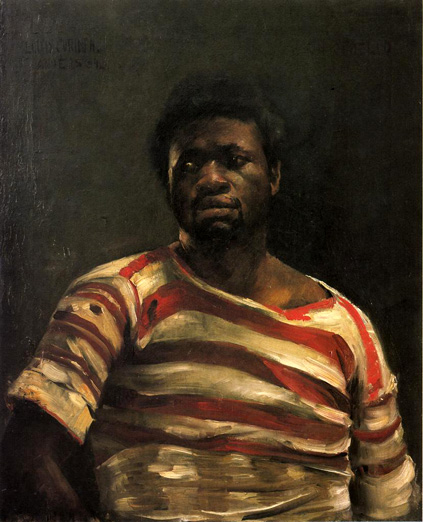

Still more vigorous, in both execution and expression, is Corinth's painting of a black man, poetically inscribed 'Un Othello' in the upper right. The shirt, painted with a broad, loaded brush in stripes of red and white, stands out boldly against the grayish black ground. The subtle turn of the torso and the figure's close proximity to the picture frame reinforce the impression of immediacy conveyed by the energetic brushstrokes. Despite the literary allusion of the title, the portrait is no more than a character study, possibly of a sailor from the Antwerp harbor; it compares favorably with Rubens's similarly sympathetic studies of foreign sailors.

Un Othello: 1884

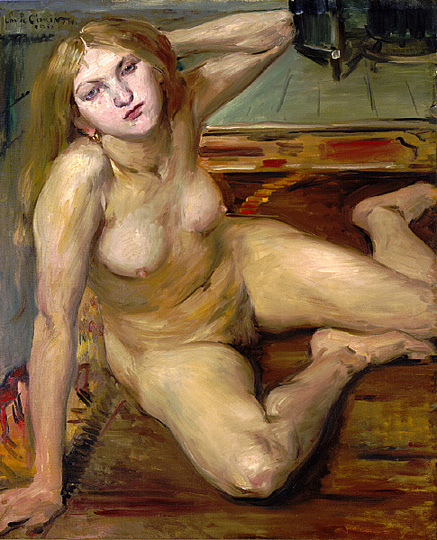

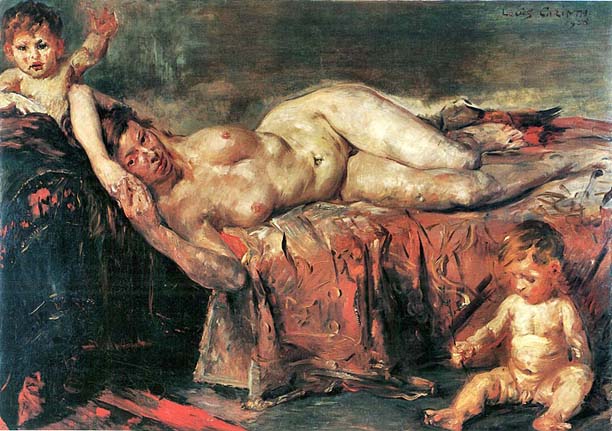

Reclining Female Nude: 1887

This 1887 painting is an ambitious effort. The model is shown life-size, reclining on a bed of silky cushions and sheets, her back turned seductively toward the viewer.

Portrait of Franz Heinrich Corinth

(Unfinished): 1888

_1888.jpg)

The portrait Corinth painted of his father when he returned home in May 1888, however, gives no indication of Franz Heinrich's illness. On the contrary, the upright posture and alert gaze convey undiminished physical and mental vigor. The sitter is seen from up close and slightly below, his head turned, almost abruptly, toward the viewer. The raised eyebrows and firm mouth give the face a look of quiet resolve. The resulting effect of controlled tension differs considerably from the calm mood of Corinth's earlier portraits of his father. Psychic energy emanates from the unfinished work, in which only the face has been given definition. The rest of the portrait is barely sketched out.

Franz Heinrich Corinth on his Sickbed: 1888

Portrait of the Painter Carl Bublitz: 1890

Bold contrasts of light and shade, induced by the bright illumination from the left, play a major part in the compositional structure of the Bublitz portrait. And the broad, energetic application of the paint itself suggests palpitating life.

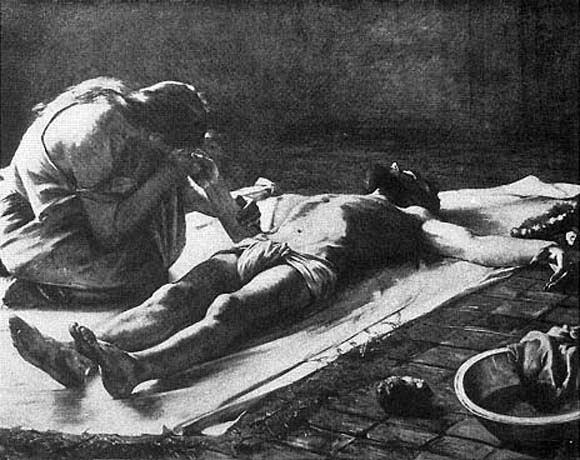

Pietà: 1889

The pictorial space in the Pietà is coextensive with the viewer's own, setting the stage for an empathic experience. The naturalistic figures, illuminated by the bright light from the upper left, lend the scene a startling and unsentimental immediacy. Indeed, a closer examination of Corinth's conception reveals less concern for emotive content than for pictorial structure. The complex pose of the Magdalene and the foreshortened figure of Jesus-set off against the white cloth and the pattern of the tiled floor-are too carefully staged to be convincing in more than formal terms. Yet the contrived composition fulfilled Corinth's highest hopes. Having exhibited the painting in Bruno Guttzeit's gallery in 1889, he sent it to the Paris Salon in 1890, where it was not only accepted but awarded the "so ardently desired" mention honorable .

Susanna in her Bath: 1890

'Susanna in Her Bath' of 1890, best known today through the somewhat more freely painted but contemporary second version of the picture in the Museum Folkwang, was also conceived with the typical Salon public in mind and, like the Pietà , can be traced to Corinth's student years in Paris. The composition depends on Henner's painting of the same subject, which Corinth knew from the collection in the Musée du Luxembourg. Like Henner's painting, the Susanna is a standard academic study from life that has been given a biblical meaning with the addition of a few anecdotal accessories. The wall in the background and the curtain through which the lecherous bearded elder peeks sets the limits of the pictorial space and provide an effective foil for the nude body of the model.

Emboldened by the favorable reception of the 'Pietà' and possibly hoping to repeat or even improve on his earlier success, Corinth sent the Susanna to the Paris Salon in 1891. This time, however, he was less fortunate, although the painting was accepted-in itself no mean achievement considering the large number of works usually rejected by the jury. No doubt the very acceptance of the painting further convinced Corinth that public approval of his work depended on his producing compositions that demonstrated his technical abilities in the context of a "significant" theme.

Das Trojanische Pferd

(The Trojan Horse): 1924

_1924.jpg)

The Trojan Horse

The Trojan Horse was a tale from the Trojan War, as told in Virgil's Latin epic poem 'The Aeneid'. The events in this story from the Bronze Age took place after Homer's Iliad, and before Homer's Odyssey. It was the stratagem that allowed the Greeks finally to enter the city of Troy and end the conflict. In the best-known version, after a fruitless 10-year siege of Troy the Greeks built a huge figure of a horse inside which a select force of men hid. The Greeks pretended to sail away, and the Trojans pulled the Horse into their city as a victory trophy. That night the Greek force crept out of the Horse and opened the gates for the rest of the Greek army, which had sailed back under cover of night. The Greek army entered and destroyed the city of Troy, decisively ending the war.

The priest Laocoön guessed the plot and warned the Trojans, in Virgil's famous line "Timeo Danaos et dona ferentes" (I fear Greeks even those bearing gifts), but the God Poseidon sent two sea serpents to strangle him, and his sons Antiphantes and Thymbraeus, before he could be believed. King Priam's daughter Cassandra, the soothsayer of Troy, insisted that the horse would be the downfall of the city and its royal family but she too was ignored, hence their doom and loss of the war.

A "Trojan Horse" has come to mean any trick that causes a target to invite a foe into a securely protected bastion or place, now often associated with "malware" computer programs presented as useful or harmless in order to induce the user to install and run them.

Diogenes: 1891

Diogenes

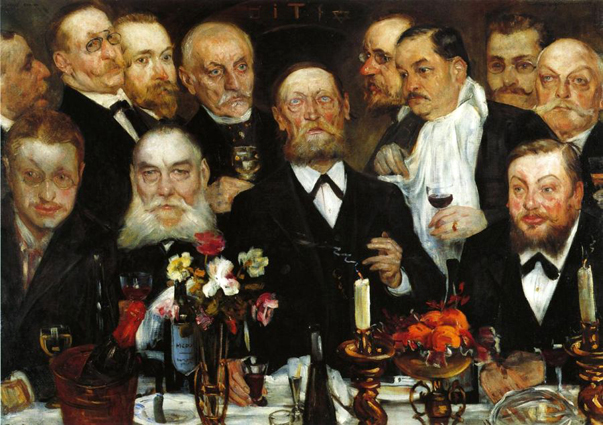

Corinth's first major painting from Munich, 'Diogenes', was the most ambitious composition he had ever attempted, with no fewer than twelve almost-life-size figures. Although the canvas bears the date 1892, Corinth must have begun work on it soon after his arrival from Königsberg, for the picture was being exhibited at the Munich Glass Palace by the end of 1891. The painting depicts the Cynic in the Athenian marketplace, his lamp lit in daylight, as he searches "for an honest man." The subject was especially popular in seventeenth-century Flemish painting. Jordaens depicted it several times, most notably in the large canvas now in Dresden. Corinth's version, however, recalls a lost composition by Rubens, a workshop copy of which is preserved in the Louvre. Diogenes stands alone, holding up his lamp; the reactions of the eight figures before him range from amused curiosity to outright derision. The postures and gestures of the two naked urchins in the left foreground are sequential, the one leaning forward, supporting his hands on his knees, the other standing upright with arms upraised. The young woman in the center continues the movement, leaning back as she shields her mocking expression with her forearm. The picture opposes old faces to young ones, clothed figures to nudes. Diogenes' weathered old skin contrasts with the youthful skin of the two boys before him. The simplified figures of the nude children in the background similarly correspond to one another. Rejecting the idealism with which subjects like this one were traditionally rendered, Corinth, moreover, went so far as to introduce figure types that might have been found in a Munich market square in the 1890's: the old woman with the basket and the couple standing at the far left. In recasting the subject in a naturalistic form, Corinth did not hesitate to translate the heroic into the commonplace. And Corinth's Diogenes was not accorded an entirely favorable reception.

Diogenes and Alexander

(An Etching)

There were many stories invented about Alexander's behavior on certain occasions; these anecdotes were all intended to show the greatness of the man. In his Life of Alexander, the Greek author Plutarch of Chaeronea has added the following story, which served to show that Alexander has some philosophical inclinations. The anecdote may well be true:

Soon after, the Greeks, being assembled at the Isthmus, declared their resolution of joining with Alexander in the war against the Persians, and proclaimed him their general.

While he stayed here, many public ministers and philosophers came from all parts to visit him and congratulated him on his election, but contrary to his expectation, Diogenes of Sinope, who then was living at Corinth, thought so little of him, that instead of coming to compliment him, he never so much as stirred out of the suburb called the Cranium, where Alexander found him lying along in the sun.

When he saw so much company near him, he raised himself a little, and permitted himself to look upon Alexander; and when he kindly asked him whether he wanted anything, 'Yes,' said he, 'I would have you stand from between me and the sun.'

Alexander was so struck at this answer, and surprised at the greatness of the man, who had taken so little notice of him, that as he went away he told his followers, who were laughing at the moroseness of the philosopher, that if he were not Alexander, he would choose to be Diogenes.

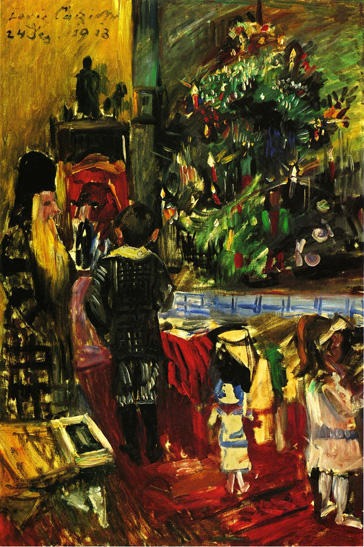

Later, having abandoned the hierarchy of genres, Corinth decided to look at scenes of daily life at the time, notably in 'Bowling Alley', 'Distributing Christmas Presents' (1913) and 'On the Beach at Forte dei Marmi' (1914).

Bowling Alley: 1913

Distributing Christmas Presents: 1913

On the Beach at Forte dei Marmi: 1914

.gif)

Donna Gravida: 1909

The portrait depicts a woman who is pregnant sitting with her left hand resting on her stomach.

Ecce Homo: 1925

Ecce Homo

After the stroke in 1911, Corinth discovered an entire new way of using color to express emotion. The pathos of his 'Ecce Homo', painted in 1925, shortly before Corinth's death, strikes even more penetratingly with the blood red garment of Jesus. The figure on the right wearing the same armor in Corinth's self portrait above bears a world-weary look on his face, in contrast to the defiance in Corinth's eyes of the self portrait. Perhaps 'Ecce Homo' hints at some remorse in Corinth at the end, a reevaluation of his nationalism in light of the human cost exacted in its name. Corinth didn't live to see the rise of Nazi Germany, but his works survived. Despite his faith in the German state and military might, Corinth's post-stroke works were deemed "degenerate art," while his pre-stroke works continued to be praised as "truly" German-an odd splitting of this deeply fractured artist.

Farmyard in Bloom: 1904

Fishermen's Cemetery at Nidden: 1893

Garden in the West End of Berlin: 1925

Goetz von Berlichingen: 1917

Grandmother and Granddaughter: 1919

Hell Fragment: ca 1901

Also known as 'The Fall', this represents a fragment of a much larger composition. Corinth seems to have been unhappy with the rest of the painting and has retained only this section. This dramatic and terrifying scene of figures tumbling towards the flames of Hell shows the sensuous paint handling and bold brushstrokes for which the artist was renowned. A disembodied claw swipes at the thigh of the man on the right, as he screams in terror. Beneath the two women at the top, a grey demon can just be seen, emerging from the darkness.

Homeric Laughter-First Version: 1909

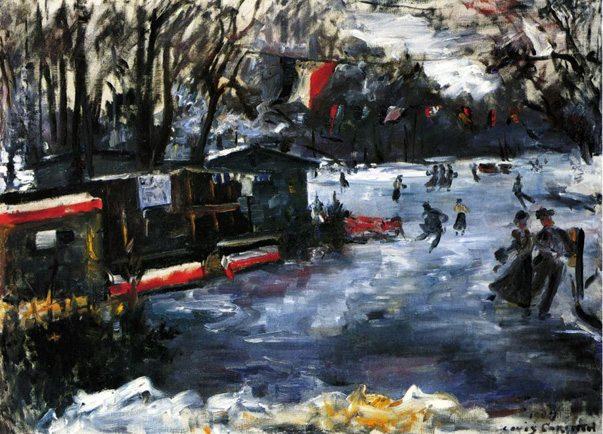

Ice Skating Rink in The Tiergarten-Berlin: 1909

In a Black Coat: 1908

In a Corset: 1910

In a Silk Robe: 1904

In the Fisherman's House: 1886

In the Woods near Bernried: 1892

Inn Valley Landscape: 1910

Flora: 1923

Lake Lucerne-Afternoon: 1924

Lake Lucerne-Morning: 1924

Large Landscape with Ravens: 1893

Luneberger Heide: 1908

Meat and Fish at Hiller's Berlin: 1923

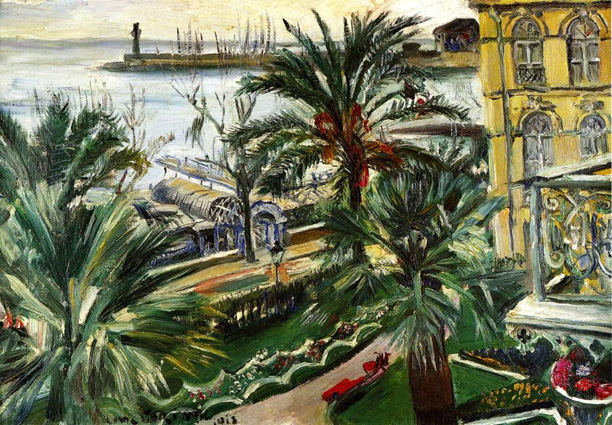

Menton: 1913

October Show at the Walchensee: 1919

Beneath the Shield of Arms: 1915

Old Man in Armor: 1915

In 1915 he responded to the news that German troops had once again freed East Prussia from Russian occupation by painting a knight as a woman's stalwart protector , inscribing the canvas "In Memory of the Assault on Memel." Two other works from 1915 commemorate German heroes-Death Mask of Frederick the Great and Martin Luther and a third depicts an Old Man in Armor; the model's feeble posture and dim gaze contrast sharply with the rigid strength of the weapons, testimony to a brave spirit seeking to defy the infirmities of old age.

On the Balcony in Bordighera: 1912

Different ambiguities mark the plein air portrait Corinth painted of Charlotte Berend on the balcony of their hotel in Bordighera . Here the problem is primarily one of pictorial structure. Despite the pronounced diagonal of the balcony railing, the painting essentially lacks perspective, resulting in abrupt transitions from the figure to the surrounding space. The vertical lines of the hotel's facade do not match, and the building appears to be leaning toward the left. The resulting impression of instability is reinforced by the diagonal shadow that falls across Charlotte's dress and by the position of her parasol, while the intense blue that dominates the color scheme adds an unexpectedly strident tone. In the landscape view at the left, the pigments are applied in predominantly parallel strokes that do not convey the varied texture of the terrain.

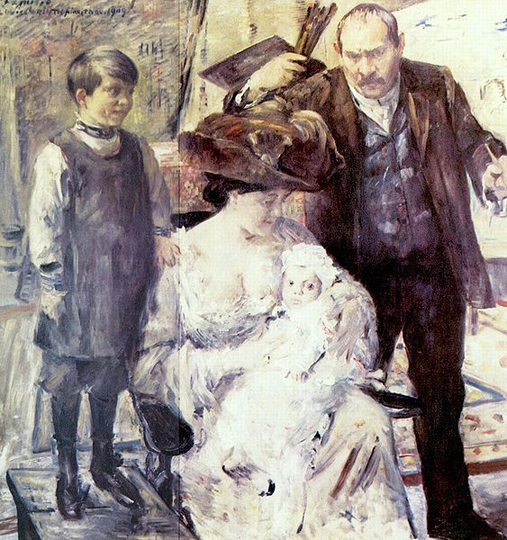

The Artist and his Family: 1909

Corinth's pictures of his young family culminated in the group portrait he painted in November 1909. According to Charlotte Berend, he prepared the painting with great care. He selected a canvas that had exactly the same dimensions as the large mirror he was using for the occasion, and he insisted that the four figures pose together as a group rather than individually. While painting, Corinth kept moving back and forth between the canvas and his place in the composition. The arrangement of the figures parallel to the picture plane might easily have resulted in a monotonous grouping had Corinth not enlivened the background with a variety of colors, textures, and shapes and allowed each figure a considerable measure of independence. The painting is indeed a study in contrasts skillfully reconciled. Thomas, who had just turned five, stands on a stool at the left and places one hand on his mother's shoulder. His attention is focused on the canvas on which Corinth is at work. Charlotte Berend, wearing a luxurious dress and a large hat, is seated in the middle, looking down at five-month-old Wilhelmine in her lap. Charlotte is the physical and psychological center of the painting, her role as mother underscored by her intimate contact with both children. Corinth shows himself in the act of painting and thus partakes of the family idyll primarily as an observer. The scattered attention of the various figures finally comes to rest on Wilhelmine, the only one in the group to look straight into the mirror. Corinth also emphasized the relationship of the figures in a coloristic fashion. White is distributed so as to predominate in Charlotte and Wilhelmine. Shades of brown link the painter and his son. Charlotte, however, shares in both colors to a significant degree and thus further unifies the family gathered around her.

The Deposition: 1895

As with the painstakingly composed Pietà in 1890, Corinth's efforts were rewarded. 'The Deposition' won a gold medal at the Munich Glass Palace in 1895 and was well received when shown at the international exhibition in Berlin the following year. A reviewer of the Berlin exhibition noted the truth and sincerity of the religious feeling he felt the painting expressed. Corinth, however, seems to have maintained a casual attitude toward the subject, for in a caricature preserved in the Lenbachhaus, he transposed the painting into a ludicrous farce. Self-irony may have led him to mock his own ambition in this way, especially since the Deposition turned out to be more than a fleeting success. Soon after the painting was shown in Berlin, Corinth sold it to Martin Feuerstein for the substantial sum of 1,350 marks. Feuerstein was himself a painter of religious subjects and later taught this genre at the Munich Academy. With this sale Corinth, then thirty-eight years old, made money from his art for the first time. As he confided to Paul Eipper many years later, hence-forth he superstitiously made the purchase price of the 'Deposition' the basis of all his price calculations, dividing or multiplying it as the occasion demanded.

The Deposition: 1906

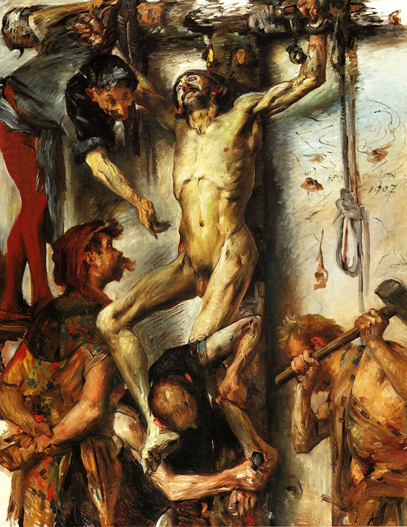

The Large Martyrdom: 1907

Susanna and the Elders: 1923

Susanna and the Elders

The Nietzsche cult of vitalism rampant in Munich in the 1890's seems to have had a liberating effect on Corinth, for his themes of conflict between man and woman mark the onset of a steamy sensuality that was to inform his works with growing frequency, particularly his depictions of the female nude. Having drawn and painted the nude for years as if it were but another form of still life, he now began to see woman both as the catalyst for man's passion and as a being capable herself of strong physical sensations. The voluptuous nude in 'Witches' is fully conscious of her charm. Her bath completed, she prepares to dress for a costume ball while several old women looking on suggestively. In the 'Temptation of Saint Anthony' the devil and the three nudes from the same episode in 'Tragicomedies' are surrounded by a considerable following, and the hermit saint finds himself not merely tempted but set upon by seductive females. Gone is the blasphemous allusion to the crucifix. Instead, the central nude spreads her arms to raise her long strands of hair as if about to descend on the saint like a bird of prey. Some of the nudes offer gifts; others seek to arouse the saint's desire or to satisfy their own. Devils and human skeletons in the background increase both the pictorial congestion and the saint's despair. Corinth's painting of the Crucifixion, Witches, Temptation of Saint Anthony and Susanna and the Elders all in the same year, and seemingly in random order, suggests something of his casual attitude toward any one theme.

Witches: 1897

The Temptation of Saint Anthony: 1897

The Temptation of Saint Anthony after Gustave Flaubert: 1908

Still Life Paintings by Lovis Corinth

Chrysanthemums and Roses in a Jug: 1917

Cala Lilies and Lilacs with a Bronze Figurine: 1920

Chrysanthemums and Calla: 1920

Autumn Flowers: 1923

Floral Still Life: 1916

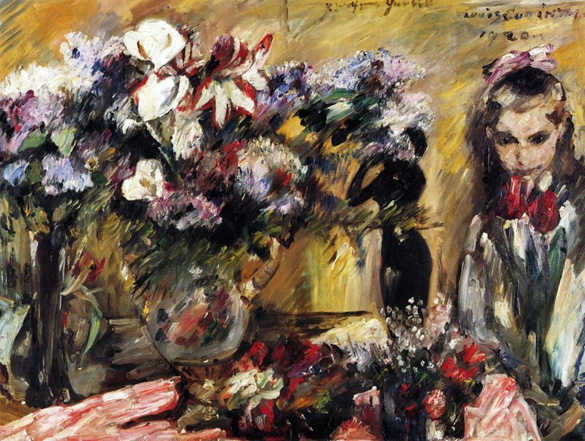

Flowers and Wilhelmine: 1920

Large Still Life with Figure: 1911

Larkspur: 1924

Lilac and Tulips: 1922

Orchids: 1923

Pink Roses: 1924

Red and Yellow Tulips: 1918

Roman Flowers in a Jug: 1914

Roses: 1910

Roses: 1911

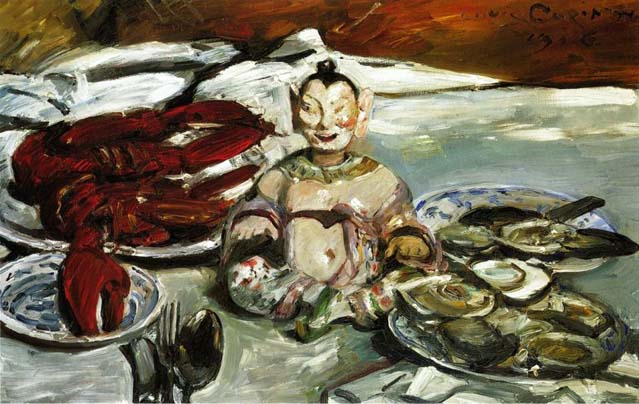

Still Life with Buddha-Lobsters and Oysters: 1916

Still Life with Chrysanthemums and Amaryllis: 1922

Still Life with Flowers, Skull, and Oak Leaves: 1915

The Hare: 1921

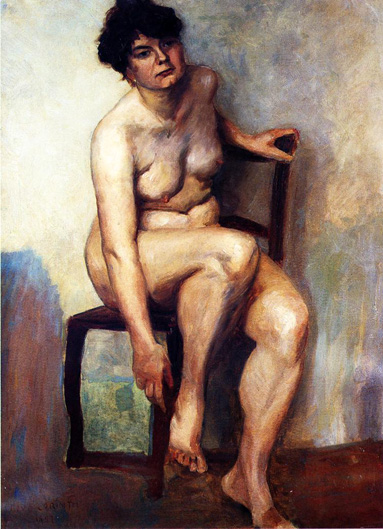

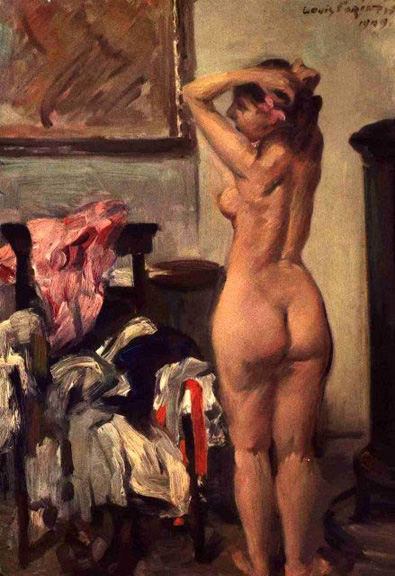

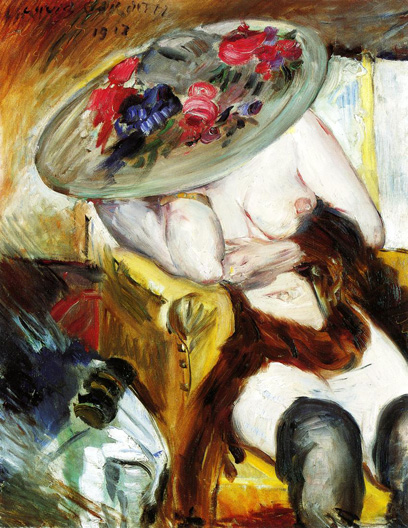

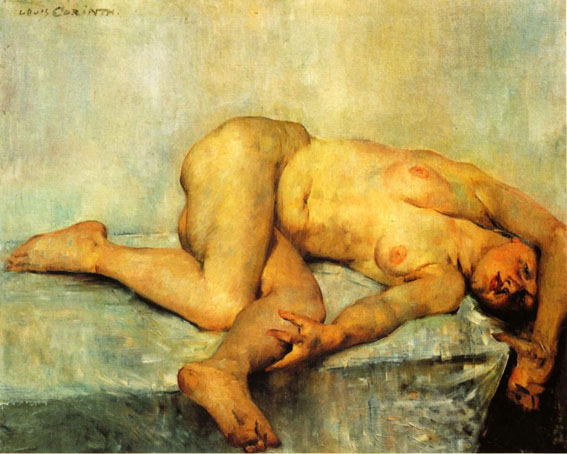

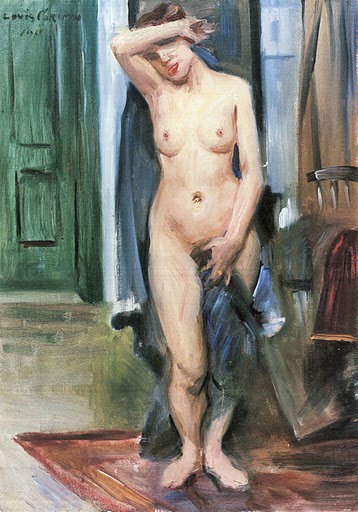

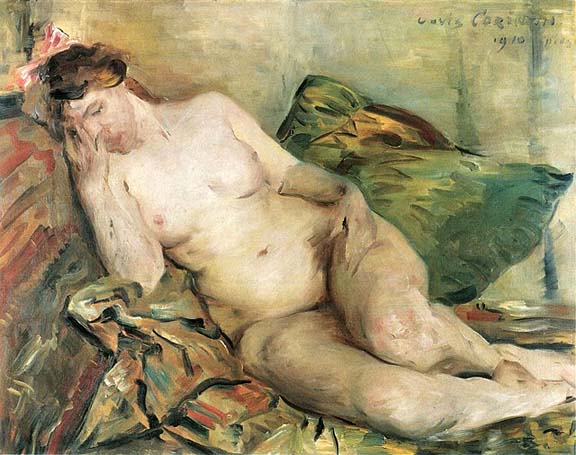

Nudes by Lovis Corinth

Corinth studied nude painting at the Académie Julian in Paris, in the 1880's. He considered this genre to be the "Latin of painting". His nude paintings became more prolific after 1904. Faithful to the Expressionist idea of blending art and life, the artist rarely selected a professional model. More often than not it was a friend, his wife or his family.

Although many of his allegorical paintings celebrated nudity, Corinth eventually removed all mythological or religious references from them. Some paintings resulted from spontaneous observations of daily life, like 'Morning' (1905) and 'After the Bath' (1906), these two compositions show his wife, his preferred model, going about her toilette.

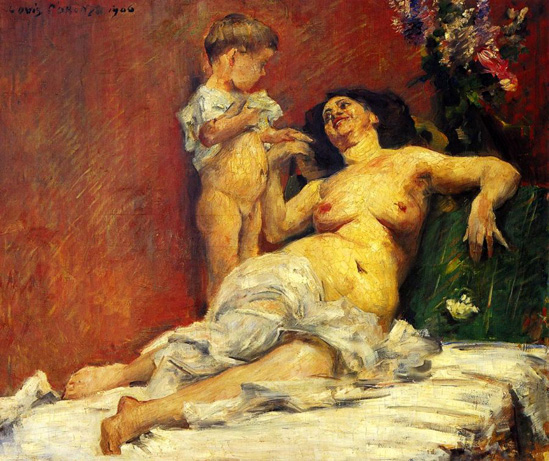

Mother and Child: 1906

In addition to several portraits of young Thomas and three more double portraits of Charlotte with Wilhelmina, Thomas, and again Wilhelmina, there are several works that invest the subject of mother and child with a more general meaning. In a painting of 1906 both Charlotte and Thomas are shown in prototypical nudity. Charlotte reclines on a couch and turns, smiling toward the boy. The flower she holds and the bouquet in the upper right corner of the composition underscore the allusion to fecundity and new life. Unfortunately, the painting is burdened by the implicit erotic appeal typical of Corinth's mature depictions of the female nude and remains much too close to the model to be convincing in generalized terms. The same facial veracity and forced expression greatly diminish the effect of 'Motherly Love', another painting of Charlotte and Thomas, from 1911.

A Mother's Love: 1911

Morning: 1900

After the Bath: 1906

Female from the Back-Nude

Female Nude: 1897

Frau bei der Toilette: 1909

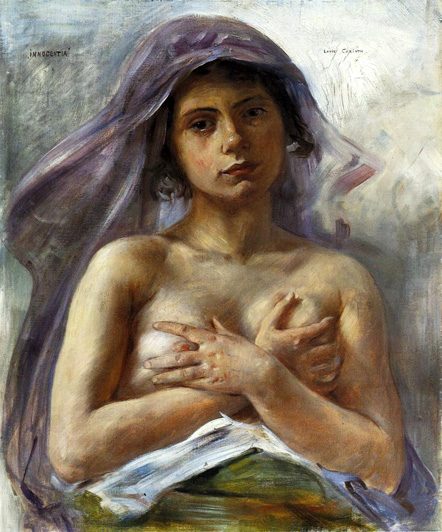

Innocentia: 1890

Italian Woman in a Yellow Chair: 1912

Matinee: 1905

Morning Sun: 1910

Nana-Female Nude: 1911

This nude was no doubt painted before Corinth's stroke in 1911.

Nude Girl on a Rug: 1912

Odysseus Fighting with the Beggar: 1903

Odysseus, disguised as a beggar, is challenged by Iros:

And now there arrived a public beggar, who used to go begging

through the town of Ithaka, known to fame for his ravenous belly

and appetite for eating and drinking. There was no real strength

in him, nor any force, but his build was big to look at.

He had the name Arnaios, for thus the lady his mother

called him from his birth, but all the young men used to call him Iros,

because he would run and give messages when anyone told him.

This man had come to chase Odysseus out of his own house

and now he spoke, insulting him, and addressed him in winged words:

"Give way, old sir, from the forecourt, before you are taken and dragged out

by the foot. Do you see how all of them are giving the signal

and telling me to drag you. Still, I am ashamed to do it.

So up, before it comes to a battle of hands between us."

Then looking at him darkly resourceful Odysseus answered:

"Strange man, I am doing you no harm, nor speaking any,

nor am I jealous, if someone takes plenty and gives it to you.

This doorsill is big enough for both of us, nor have you any

need to be jealous of others. I think you are a vagabond

as I am too. Prosperity is in the gods' giving.

Leave blows alone, do not press me too hard, or you may make me

angry so that, old as I am, I may give you a bloody

chest and mouth. Then I could have peace, and still more of it

tomorrow, for I do not think you will make your way back here

a second time to the house of Odysseus, son of Laertes."

Then in anger Iros the vagabond said to him:

"Shame on how the old hulk rolls along in his speech, like

an old woman at the oven. I have some bad plans for him:

hit him with both hands, and spatter all of the teeth out

from his jaws on the ground, as if he were a wild pig rooting

the crops. Come, tuck up, so all these people can see us

do battle. But how can you fight against a man who is younger?"

From: The Odyssey

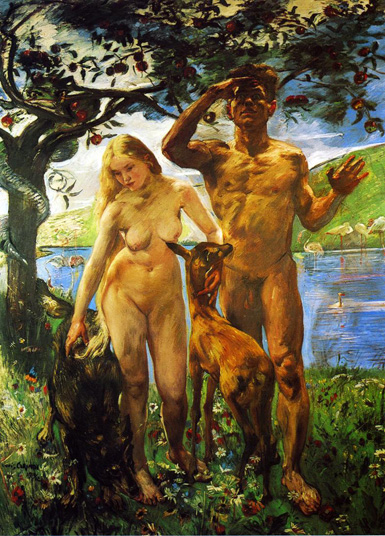

Paradise: 1911

Mia, a Corinth Nude

Nudity is and will probably always be disputed, so the effect of this painting would make no difference. Perhaps even having a few live nudes, I doubt, would be of dispute though.

My Opinion - Senex

A quote by William Blake could also be tactfully displayed and appreciated.

"Art can never exist without naked beauty displayed."

Reclining Female Nude: 1907

Reclining Nude: 1899

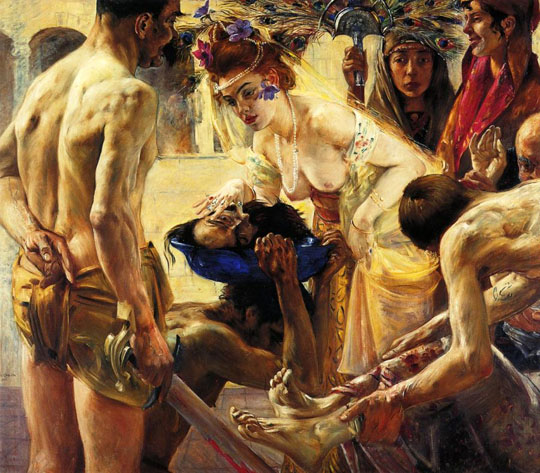

Salome-First Version: 1899

Salome-Second Version: 1900

Standing Nude

The Children of Zeus: 1905

The Fair Imperia: 1925

The Magdalen with Pearls in her Hair: 1919

Mary Magdalen is a Biblical figure who is frequently portrayed as a prostitute. The subject provided Corinth with an opportunity for a powerful depiction of the female body. Her bare torso fills the composition, her splayed hand emphasizing her breasts. The pose implies a dangerous sexuality. The introduction of the skull, however, is a reminder of passing beauty and, ultimately, of mortality.

The Harem

Several of Corinth's figure compositions are actually no more than expanded studies of the nude model, a number of figures having been grouped together in some fashion. These paintings usually bear rather perfunctory titles that more or less describe what is shown. They include 'The Graces', a depiction of three standing female nudes in almost sequential and complementary front, back, and side views, and Girl Friends, two pictures in which four nude models in a variety of postures crowd around a chaise lounge. In Harem Corinth modified this subject only slightly by adding the figure of a black eunuch. The delightful little cat in the foreground gazes attentively out of the picture and by its prim composure accentuates the languid sensuality of the four women. No wonder pictures like this helped to establish Corinth as one of the great modern painters of the female nude and gained him the reputation of a man himself possessed of a robust libido. It is impossible to say to what extent this reputation was justified. Apparently, however, Corinth believed that the sensual life of artists was intimately bound up with their creative activity, and he is said to have insisted that artists not deprive themselves of sexual gratification, since erotic experiences are wont to increase their creative energy. In his autobiography Corinth expressed a similar opinion when he spoke of his belief that sexual contact enhances an individual's emotional life.

The Three Graces: 1920

Potiphar's Wife: 1914

Resting

The Nudity

Paintings and Portraits

Paddel-Petermannchen: 1902

Charlotte Berend-Corinth, wife of Lovis Corinth

Charlotte Berend on a Stool

Charlotte Corinth at her Dressing Table: 1911

Paraphrase: 1907

Paul Bach: 1919

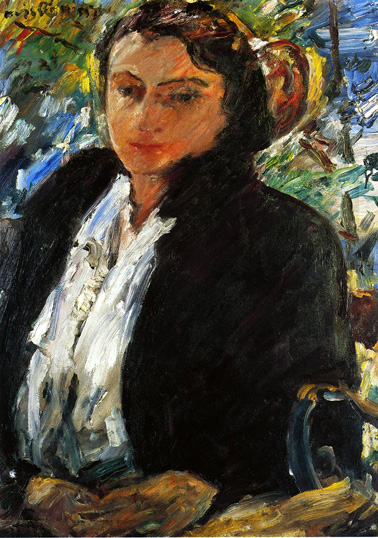

Petermannchen: 1902

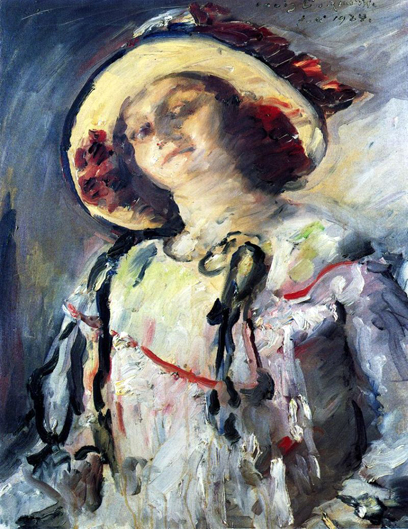

Lovis Corinth painted this portrait of a young woman during a holiday together on the Baltic coast. The portrait subject, Charlotte Berend, was daughter to a Jewish merchant family and took lessons with the well-known painter as an escape from bourgeois constraints. She became one of his favorite pupils and the couple were engaged later in 1902, the same year that this picture was painted.

Corinth was already exploring the limits of convention through the subject's casual stance, with head back and shoulders uncovered, suggestive of the sensual, erotic portraits he went on to paint of Charlotte Berend in the years that followed. Hidden in the picture is a dedication from the artist to his lover: Barely visible on the back of the chair "Mein Petermannchen" is written. She herself traced this nickname back to a harmless, amusing story. But Corinth was probably aware of the other meaning: The "Petermannchen" is a fish that can suddenly bristle and injure badly.

Lovis Corinth had many Jewish commissioners, as numerous portraits prove. This one of his future wife is evidence of the dialog between two artists and at the same time evocative of the picture of a "beautiful Jew." It tells of the tension between the Jewish identities around and beyond religion and bourgeoisie.

Following her marriage, Charlotte Berend increasingly put her own artistic work behind that of her husband, although she continued to belong to and exhibit at the Secession. In 1939, she emigrated to New York where she opened an art school.

Portrait of a Man: 1879

The small painting in Hamburg of an unidentified man exemplifies these early studies in oil. The averted gaze and inanimate expression indicate that Corinth grasped the sitter's image primarily in its characteristic form and appearance; the extreme close-up view allowed him to explore facial details fully. The modeling is smooth and reveals a thorough understanding of the interaction of facial muscles and bone structure.

Portrait Frau Behn: 1886

Portrait of a Lady: 1886

Portrait of a Woman in a Purple Hat: 1912

Portrait of Alfred Kerr: 1907

Alfred Kerr, born Alfred Kempner, was an influential German-Jewish theatre critic and essayist, nicknamed the Kulturpapst ("Culture Pope").

Kerr was born into a prosperous family in Breslau, Silesia, taking the surname Kerr in 1887, and making the change officially in 1909. He studied literature in Berlin with Erich Schmidt. He subsequently was a reviewer for numerous newspapers and magazines. With the publisher Paul Cassirer he founded the artistic review Pan in 1910.

Kerr was noted for his treatment of drama criticism as another branch of literary criticism. As his fame grew he engaged in polemics, with the critics Maximilian Harden and Herbert Ihering in particular. In the 1920's he was hostile to Bertolt Brecht, and attacked him with accusations of plagiarism. In 1933 Kerr and his family fled Germany for London via Czechoslovakia, Switzerland, and France. These years of exile were described, from a child's perspective, by Kerr's daughter in her book 'When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit'. His books were amongst those burnt in May 1933 by the Nazis when they came to power; Kerr had attacked the Nazi Party publicly, and he had already gone into exile with his family. After visiting Prague, Vienna, Switzerland, and France, he came to London in 1935 where he settled, in penury. He was a founder of the Freier Deutschen Kulturbund, and worked for the German PEN club. An old feud with Karl Kraus worked against him in some quarters.

Kerr took British citizenship in 1947. In 1948 he visited Hamburg at the start of a planned tour of several German cities but suffered a stroke, and then decided to end his own life (overdose of sleeping pills procured by wife).

The Alfred-Kerr-Preis für Literaturkritik was established in 1977. As of 2004 his works are once more available and widely read in Germany.

His son Michael Kerr was a prominent British jurist. His daughter Judith Kerr wrote a three-volume autobiography; the writer Matthew Kneale is her son with Nigel Kneale, the writer of Quatermass scripts.

Portrait of Charlotte Berend in a White Dress: 1902

Charlotte Berend studied fine arts at the Berliner Kunstgewerbe museum taught by Eva Stort and Max Schäfer. From 1901 she was the first student at the private art school of the painter Lovis Corinth, who fell in love with her. She became his model for a number of paintings, including 'Portrait of Charlotte Berend in a White Dress'. On March 26, 1903, she married Lovis Corinth and changed her name to Berend-Corinth. On October 13 the same year their son Thomas Corinth was born, and their daughter Wilhelmina Corinth followed six years later on June 13, 1909.

Beginning in 1906, Charlotte Berend-Corinth showed her paintings at the Berliner Secession, and she joined the Secession in 1912 and did not leave it after the separation of the new Freie Secession led by Max Liebermann when Lovis Corinth became the new head of it. She draw painted book illustrations for Max Pallenberg, Fritzi Massary, and Valeska Gert and painted portraits of Michael Bohnen, Werner Krauss, Paul Bildt, and Paul Graetz. In the 1920's she supported young artists from the theatres in Berlin. In 1919 Lovis Corinth bought a house in Urfeld at Walchensee were he and his wife could retire from the life in Berlin. Corinth here painted landscapes, portraits and still-lifes and more and more retired from the active arts scene. He died in 1925 during a journey to the Netherlands.

Charlotte Berend-Corinth emigrated in 1933 with her children to the United States of America and lived in New York. 1958 she published the book of the complete paintings of her husband Lovis Corinth, which became a standard and was in use until today in a new version of Béatrice Hernad from 1992. Charlotte Berendt-Corinth died in 1969.

Portrait of Charlotte Berened-Corinth in a Green Velvet Jacket: 1921

Portrait of Dr. Karl Schwarz: 1916

Portrait of Eduard, Count Keyserling: 1900

Eduard Graf von Keyserling was a Baltic German fiction writer and dramatist and an exponent of literary Impressionism.

Keyserling was born at Schloss Tels-Paddern, Courland Governorate, within the Russian Empire, now Kalvene parish, Liepaja District in Latvia. He belonged to an ancient family of Baltic German nobility and was a cousin of the philosopher Hermann Keyserling. He died in Munich, Bavaria.

Keyserling's early novels Fräulein Rosa Herz. Eine Kleinstadtliebe (1887) and Die dritte Stiege (1892) were influenced by Naturalism. His essays on general and cultural questions, like his theater plays, are forgotten. His narrative, novellas and novels, after 1902, place Keyserling at the forefront of German literary Impressionism.

A subtle and elegant stylist, Keyserling's narrative is unforgettable for its evocative ambience and "feel". His most emblematic work is perhaps Fürstinnen (Princesses), only superficially related to the typical German 19th century Schlossroman. Somehow midway between Ivan Turgenev and Franz Kafka, there is a certain pessimistic kinship between Keyserling and Anton Chekhov.

Portrait of Eleonore von Wilke, Countess Finkh: 1907

Portrait of Elly: 1889

Portrait of Franz Heinrich Corinth with a Glass of Wine: 1883

Portrait of Frau Hedwig Berend, Rosa Matinee: 1916

Portrait of Frau Luther: 1911

Portrait of Friedrich Ebert: 1924

Portrait of Georg Brandes: 1925

Portrait of Gerhart Hauptmann: 1900

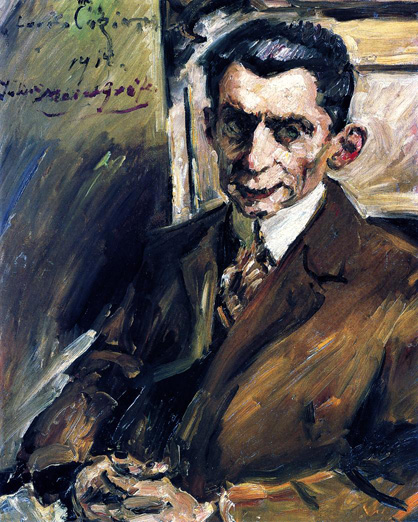

Portrait of Julius Meier-Graefe: 1917

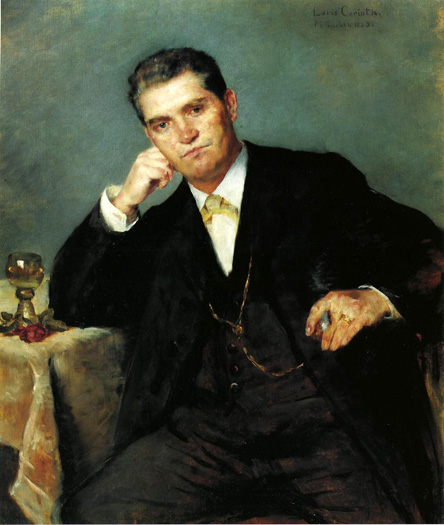

This painting brings together two major figures in German art in the early 20th century: the artist Lovis Corinth and the writer and art critic Julius Meïer-Graefe. The former, born in East Prussia in 1858, received a cosmopolitan education. Until 1911, he produced symbolist painting with a post-romantic tinge. His technique revealed the influence of French Naturalists such as Dagnan-Bouveret, who was one of Corinth's teachers in Paris. After 1911 and an apoplectic fit which radically upset his life, his brushstrokes and palette changed, sometimes achieving a spirited style which prefigured expressionism. From then on, his long brushstrokes modeled or fragmented forms which were lit up with a subtle range of colors as in this portrait.

The model, Julius Meïer-Graefe, was born in Hungary in 1867 and had been a major figure in Berlin society since 1895, when he founded the magazine Pan. Meïer-Graefe's cosmopolitism and his magazine kept German artists and art lovers up-to-date on the arts in Europe; he also introduced them to Impressionism and its later developments, which became the ferment of new ideas and new approaches to art.

Portrait of Max Halbe: 1917

Max Halbe was a German dramatist and main exponent of Naturalism.

Halbe was born at the manor of Güttland near Danzig (Gdansk), where he grew up. In 1883 he started to study law at the University of Heidelberg and obtained his Doctorate at the University of Munich in 1888. After that he moved to Berlin, where he published his primary work "Jugend" (youth) in 1893, which was next to Gerhart Hauptmann´s "Die Weber" the most successful contemporary stage play in Germany. 1895 Halbe went to Munich again, where he founded the "Intime Theater für dramatische Experimente" (intimate theater of dramatic experiments) and was a co-founder of "Münchner Volksbühne" - theater. He was an important member of the Munich artist society and a friend of Frank Wedekind and Ludwig Thoma.

In 1933 and 1935 his biography "Scholle und Schicksal" and "Jahrhundertwende" were published.

Halbe died when he was 79 at his manor house in Neuötting, Bavaria.

Today Halbe as a dramatist is almost forgotten and his works are rarely acted at theaters.

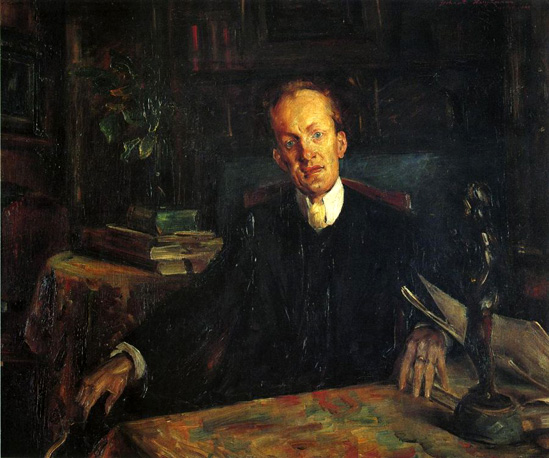

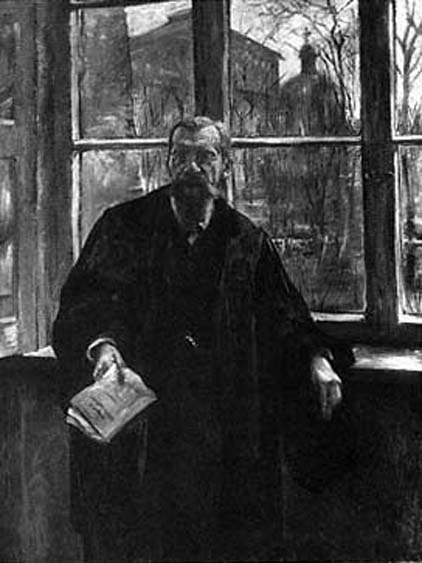

Portrait of Professor Eduard Meyer: 1910

Alfred Lichtwark, who was keenly interested in the history of portraiture in the Hanseatic city-state and had published a book on the subject in 1899, urging that the tradition be encouraged and continued. Lichtwark also personally commissioned from Corinth a portrait of Eduard Meyer for the Hamburg Kunsthalle. Meyer was a professor of history at the University of Berlin and a native of Hamburg. For Corinth this commission was particularly important since by 1910 the Hamburg museum owned twenty-nine paintings by Liebermann and one by Slevogt but none by Corinth himself. Correspondence about this commission shows the extent to which Lichtwark's own views influenced the painter.

Lichtwark first approached Corinth about the Meyer portrait in November 1910. Since at the time Meyer was dean of the Philosophical Faculty at Berlin, Lichtwark suggested that the professor be depicted in academic dress standing by a large window in the dean's office, a suggestion that was not at all frivolous. Lichtwark clearly envisioned a portrait of some official character that would blend with other paintings already in the Kunsthalle collection, such as Liebermann's portrait of Mayor Carl Friedrich Petersen (1891) and Slevogt's portrait of Mayor William Henry O'Swald (1905), in both of which the sitters are depicted in their robes of office. As it turned out, Meyer rejected the idea as too pretentious and persuaded Corinth to paint him wearing an ordinary suit and in the privacy of his study. Eduard Meyer (1855-1930) is seated nearly full-length before shelves filled with books, with what appears to be the corner of a window in an adjacent room at the upper left; the bright light entering from the right is reflected off the floor. Corinth made no effort to diminish the coarseness of Meyer's features, carefully emphasizing the facial characteristics, just as he attentively modeled the sitter's hands. Although the portrait ostensibly captures Meyer's habitual pose in casual conversation, there is a stiffness about the sitter that is reinforced by the restricted space and the well-ordered division of the background.

Corinth had completed the portrait by January 10, 1911, and a few weeks later sent it to Hamburg. Lichtwark was shocked when he first saw the painting and in a letter dated February 14 informed Corinth of his reaction. He was especially taken aback by the intensity of Meyer's gaze, and it seemed to him that the bright spot beneath the chair, in conjunction with the wall of books, virtually forced the sitter outside the picture frame. Although he acknowledged that he was gradually getting used to the portrait, he suggested that since Corinth now knew Eduard Meyer better, perhaps he could paint him a second time, but-as a pendant to the informal first portrait-wearing academic dress and standing by the large window in the dean's office, as first suggested. As an added inducement, it seems, Lichtwark in the same letter mentioned commissioning from Corinth a Hamburg landscape, a project that soon materialized.

Meyer finally consented to Lichtwark's wish for a more "official" portrait, and Corinth began work on the second painting in late March. The portrait follows Lichtwark's suggestions in virtually every respect. Meyer now wears a dark ultramarine academic robe; but his posture is relaxed, informal. Holding a velvet cap in one hand and a manuscript in the other, he leans on the windowsill in a moment of quiet concentration and reflection. The pages he holds add brightness to the lower left of the composition, balancing the bright expanse of the window. Because window and wall no longer run parallel to the picture plane, as they do in the first portrait, the interior space seems more ample, and the large window extends the view out to a spring day enlivened only by a few specks of green and the pink of a bed of hyacinths. Knobelsdorff's elegant opera house on Unter den Linden and the cupola of Saint Hedwig's Cathedral can be seen through the still-barren trees. Since the figure is illuminated from the back, Corinth was able to dispense with the details of individual forms, except for Meyer's head. With the summary treatment of the robe and the hands, however, the head acquires a spiritual strength that transfigures Meyer's countenance, lending him the dignity appropriate to his station in life.

Portrait of Eduard Meyer as Dean: 1911

Portrait of Rosenhagen's Mother: 1899

Portrait of Sophie Cassirer: 1906

Portrait of the Artist's Uncle Friedrich Corinth: 1900

Portrait of the Painter Benno Becker: 1892

Portrait of the Painter Bernt Gronvold: 1923

Portrait of the Painter Karl Strathmann: 1895

Portrait of the Painter Leo Michelson: 1922

Portrait of the Painter Leonid Pasternak: 1923

Portrait of the Painter Otto Eckmann: 1897

Otto Eckmann was a German painter and graphic artist. He was a prominent member of the "floral" branch of Jugendstil. He created the Eckmann typeface, which was based on Japanese calligraphy.

Otto Eckmann was born in Hamburg, Germany in 1865. He studied at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Hamburg and Nuremberg and at the academy in Munich. In 1894, Eckmann gave up painting (and auctioned off his works) in order to concentrate on applied design. He began producing graphic work for the magazines Pan in 1895 and Jugend in 1896. He also designed book covers for the publishers Cotta, Diederichs, Scherl and Seemann, as well as the logo for the publishing house S. Fischer Verlag. In 1897 he taught ornamental painting at the Unterrichtsanstalt des Königlichen Kunstgewerbemuseums in Berlin. In 1899, he designed the logo for the magazine Die Woche. From 1900 to 1902, Eckmann did graphic work for the Allgemeine Elektrizitätsgesellschaft (AEG). During this time, he designed the fonts Eckmann (in 1900) and Fette Eckmann (in 1902), probably the most common Jugendstil fonts still in use today.

Eckmann died on June 11, 1902 in Badenweiler, Germany.

Portrait of the Painter Paul Eugene Gorge: 1908

Portrait of the Painter Walter Leistikow: 1900

Portrait of the Painter Walter Leistilow: 1893

Portrait of the Pianist Conrad Ansorge: 1903

This very different portrait of the pianist Conrad Ansorge (1862-1930) is also perceptive. Here again Corinth set out to fathom the enigmatic inner life of a creative individual, and his approach to the task is as unconventional as it is successful. One might expect, for instance, to see Ansorge at the piano or, possibly, in the privacy of his study. Instead Corinth painted the musician outdoors, seated in the garden as if relaxing after a walk. What is more, Corinth divided the pictorial field so as to give equal physical weight to the sitter and the landscape. Coloristically, too, these parts of the composition balance, the white of Ansorge's suit holding its own against the green and earth tones of the garden. From an expressive point of view, however, the musician's spiritual presence dominates the painting. The fence in the background and the vertical axis of the chair lead resolutely to Ansorge's head, which forms the psychological, if not the physical, center of the composition. Even the outdoor light is not allowed to interfere with the modeling of the thoughtful face, encroaching on the sitter only in the quick brush-strokes with which Corinth accented the folds of the suit. Whereas the portraits of Keyserling and Hille bear witness to precarious physical and emotional states, the portrait of Ansorge is the very image of equanimity.

Ansorge, who looks older than his forty-one years, was just beginning his great international career. A native of Silesia, he had studied with Franz Liszt and in 1887 completed a successful first tour of the North American continent. He made his home in Berlin in 1895 but traveled all over Europe and South America giving concerts and recitals. He was especially acclaimed for his interpretation of the great Romantics, Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, and Chopin; but he was also a keen champion of the works of contemporary composers and himself set to music texts by Stefan George, Alfred Mombert, and Stanislaw Przybyzewski. Though famous for his command of the keyboard, Ansorge despised the pursuit of virtuosity for its own sake and distinguished himself among the pianists of his generation by faithfully adhering to a composer's intentions. Sensitivity and intelligence were the hallmarks of his playing and earned him the love and respect of his many students. Corinth, too, perceived the spiritual side of Ansorge as his very essence and underscored it in the portrait.

Portrait of the Poet Herbert Eulenberg: 1924

Portrait of the Poet Peter Hille: 1902

When he painted the portrait of the poet Peter Hille (1854-1904), Corinth found himself face-to-face with an incorrigible eccentric, and he responded with a character study that, while less subtle, equals in perception the portrait of Eduard von Keyserling. Hille's shabby appearance and unconventional demeanor made him a curious sight in the bourgeois milieu of the German capital. Yet he was tolerated in the city's intellectual and artistic circles, where he showed up unannounced, carrying a large satchel filled with voided streetcar tickets and the other scraps of paper on which he scribbled his poems and epigrams. Aversion to discipline and disregard for bourgeois conventions were among Hille's character traits, along with an almost childlike innocence that accounted for much of his popularity. Hille, a native of Erwitzen, near Paderborn, rebelled early against the strictures of family life. After working briefly in the late 1870's in Bremen, on the editorial staff of the Deutsche Monatsblätter and the Bremen Tageblatt , he tried to establish himself as an independent writer in Leipzig. When this effort failed, he went to London to study in the library of the British Museum but spent most of his time from 1880 to 1882 in the slums of Whitechapel. He subsequently traveled, mostly on foot, as far as Italy and Hungary. While serving as the manager of a small troupe of itinerant actors in Holland, he squandered what remained of a small inheritance from his mother. Although Hille gained recognition in the late 1880's for his novel Der Sozialist (1887), he is remembered now more for his Bohemian life-style than his literary output. Always neglectful of his health, he died of a lung hemorrhage in Berlin at the age of forty-nine.

Corinth has spoken of the circumstances that led to the Hille portrait. When he mentioned to Peter Behrens that he was in search of an interesting-looking model, Behrens called Hille to his attention, warning him that the talkative poet was wont to make interminable visits. When Hille came to call on Corinth and began to remove his outer garments, the painter, remembering Behrens's words of caution, quickly told him: "Don't bother. I'll paint you just the way you are." In the large, life-size portrait Peter Hille is indeed still dressed in his overcoat, his hat on his knee. But the anecdote alone hardly explains the painter's conception; only deliberate artistic decisions could have produced so apt a characterization. Everything about the sitter speaks of his restless nature-his fidgety posture, the folds of his coat, and the crumpled hat and sheets of newspaper-and Hille imparts this restlessness to his immediate surroundings, as in the squashed-down pillow at the left. He hovers on the edge of the sofa, his feet hardly seeming to touch the floor, and his gaze is turned upward as if something had suddenly caught his attention. The unusually well-ordered pictorial structure accentuates the disquiet of his bearing. The lines of the sofa and the shelf above it divide the canvas horizontally into parallel planes, providing a sense of stability at odds with the poet's restive figure. The conch shell and the small bust-perennial appurtenances of bourgeois culture-on the shelf above him further signify a world in which Peter Hille is no more than a itinerant guest.

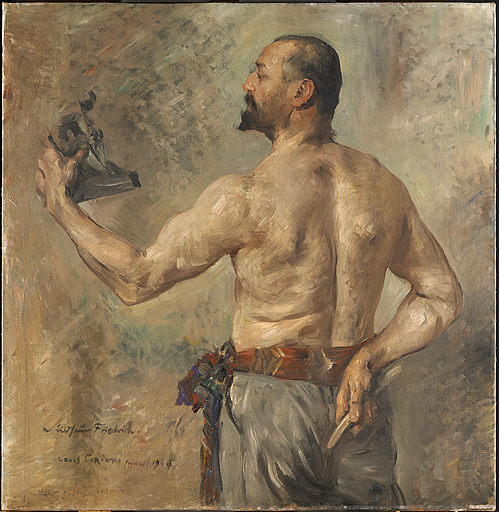

Portrait of the Sculptor Friedrich: 1904

Portrait of Wilhelmine with her Hair in Braids: 1922

Portrait of Wolfgang Gurlitt: 1917

Punt in the Reeds at Muritzsee: 1915

Red Christ: 1922

Rudolph Rittner as Florian Geyer - First Version: 1906

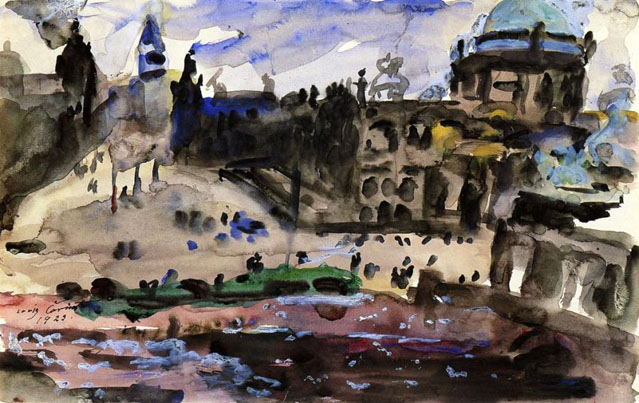

Schlossfreiheit-Berlin: 1923

Schlossfreiheit-Berlin: 1923

The Abduction: 1918

The Black Mask: 1908

The Family of the Painter Fritz Rumpf: 1901

The Freemasons: 1899

The Jochberg and the Walchensee: 1924

The New Pond in the Tiergarten, Berlin: 1908

The Sea near La Spezia: 1914

Thomas and Wilhelmine: 1916

Thomas Corinth in Sailor Suit: 1920

Thomas in Armor: 1925

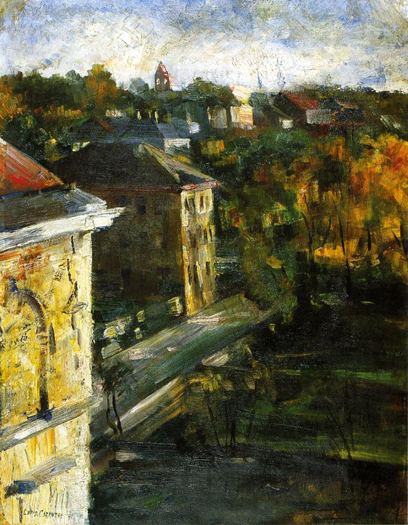

View from the Studio: 1890

View from the Studio Window: 1891

View from the Studio, Schwabing: 1896

View of the Kohlbrand, Hamburg: 1911

Walchensee: 1920

Wilhelmine in a Yellow Hat: 1924

Wilhelmine in the Green Dress: 1924

The Violinist: 1900

The Walchensee in the Moonlight: 1920

Wilhelmine with a Ball: 1915

Woman by a Goldfish Tank: 1911

Woman in a Deck Chair by the Window: 1913

Woman with a Glass of Wine: 1908

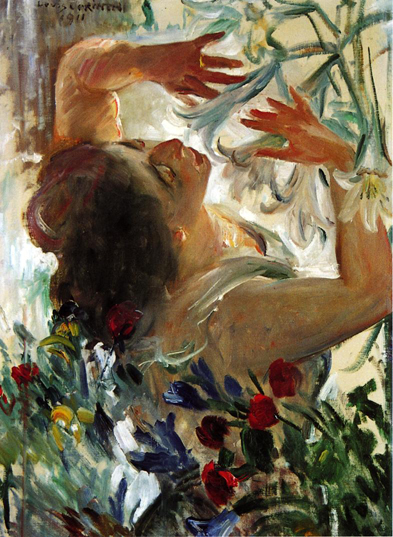

Woman with Lilies in a Greenhouse: 1911

Woman with Rose Hat: 1912

Corinth's recovery in Bordighera of his ability to communicate a visual impression in a commensurately evocative form is seen in yet another portrait of Charlotte Berend. The portrait was prompted, as so often in the past, by Charlotte's habit of striking an artful pose, this time with a white fur cape draped casually over her shoulder. The couple had just returned to their hotel room from a ride in the town's annual spring flower parade, and the lingering joy of the shared experience seemingly allowed both painter and model to dispel the tensions that might otherwise have interfered with the felicitous conception. In this painting Corinth managed to recapture the intimacy that characterizes his earlier portraits of Charlotte. The fashionable dress and hat reinforce her vivacity and charm, while the extreme close-up view allows for a maximum of psychological rapport. Corinth set himself here the challenging task of painting against the light, and any lack of detail follows logically from the strong contrasts in illumination. Only in Charlotte's face, shielded by the brim of her hat and thus less susceptible to the form-dissolving effects of the enveloping light, do the brushstrokes delineate the familiar traits with greater precision.

Source: Art Renewal Center

Source: Lovis Corinth Online

Source: Lovis Corinth by Horst Uhr

Berkeley: University of California Press

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.