Netherlands Northern Renaissance Painter and Draftsman

1435 - 1494

Hans Memling was a Flemish painter, whose art gave luster to Bruges in the period of its political and commercial decline. Though much has been written respecting the rise and fall of the school which made this city famous, it remains a moot question whether that school ever truly existed. Like Rome or Naples, Bruges absorbed the talents which were formed and developed in humbler centers. Jan Van Eyck first gained repute at Ghent and The Hague before he acquired a domicile elsewhere, and Memlinc, we have reason to think, was a skilled artist before he settled at Bruges. The annals of the city are silent as to the birth and education of a painter whose name was inaccurately spelt by different authors, and whose identity was lost under the various appellations of Hans and Hausse, or Hemling, Memling, and Memlinc. But W. H. J. Weale mentions a contemporary document discovered in 1889, according to which Memlinc "drew his origin from the ecclesiastical principality of Mayence," and died at Bruges on the 11th of August 1494. He probably served his apprenticeship at Mayence or Cologne, and later worked under Rogier van der Weyden. He did not come to Bruges until about 1467 and certainly not as a wounded fugitive from the field of Nancy. The story is fiction, as is also the report that he was sheltered and cured by the Hospitallers at Bruges, and, to show his gratitude, refused payment for a jicture he had painted. Memlinc did indeed paint for the Hospitallers, but he painted not one but many pictures, and he did so in 1479 and 1480, being probably known to his patrons of St John by many masterpieces even before the Battle of Nancy. Memlinc is only connected with military operations in a mediate and distant sense. His name appears on a list of subscribers to the loan which was raised by Maximilian of Austria to push hostilities against France in the year 1480. In 1477, when he is falsely said to have fallen, and when Charles the Bold was killed, he was under contract to furnish an altarpifce for the gild-chapel of the booksellers of Bruges; and this altarpiece, now preserved, under the name of the Seven Griefs of Mary, in the gallery of Turin, is one of the fine creations of his riper age, and not inferior in any way to those of 1479 in the Hospital of Saint John, which for their part are hardly less interesting as illustrative of the master's power than the Last Judgment in the Cathedral of Danzig. Critical opinion has been unanimous in assigning the altarpiece of Danzig to Memlinc; and by this it affirms that Memlinc was a resident and a skilled artist at Bruges in 1473; for there is no doubt that the Last Judgment was painted and sold to a merchant at Bruges, who shipped it there on board of a vessel bound to the Mediterranean, which was captured by a Danzig privateer in that very year. But, in order that Memlinc's repute should be so fair as to make his pictures purchasable, as this had been, by an agent of the Medici at Bruges, it is incumbent on us to acknowledge that he had furnished sufficient proofs before that time of the skill which excited the wonder of such highly cultivated patrons.

_1467_71.jpg)

Although it was one of Memling's first creations in Bruges, it already displays impressive mastery. The work was commissioned by Angelo Tani (1415-1492), the Florentine manager of the Medici bank in Bruges, for the altar of his newly founded chapel in the church of the Badia Fiesolana in Florence. The commission coincided with Tani's wedding in 1466 to Caterina Tanagli, with whom he is portrayed on the closed wings. The painting was completed before the birth of the couple's first daughter in 1471, and was dispatched to Porto Pisano via Southampton in 1473. But while the ship was still in Zealand waters, it was intercepted by a Polish warship operating on behalf of the Hanseatic League. The League was engaged at the time in a boycott of trade with England, the interim destination of the vessel carrying the altarpiece. The painting was taken to Danzig (Gdansk), where it was to remain.

The composition is a reformulation of Van der Weyden's Beaune altarpiece, with a number of noteworthy quotations and differences. Rogier's extremely wide, layered and hieratical image has been reduced, made narrower and clarified by diminishing the disproportionate relationship between the divine and earthly spheres. The central, monumental figures remain Christ and Saint Michael with the Scales, and the bank of cloud is also paraphrased. The archangel dressed as a priest has, however, been transformed into a soldier. The Christ figure is as good as a copy - a remarkable and unique occurrence in Memling's oeuvre. If we throw in the strongly Rogierian style of the apostles' heads, it is almost impossible not to conclude that Memling saw the Beaune altarpiece with his own eyes.

_Two_1467_71.jpg)

_Three_1467_71.jpg)

_1467_71.jpg)

Several of the male redeemed souls have clearly personalized features, as remarked by several authors, suggesting that acquaintances of the donor had their portraits included. That this is indeed the case is supported by the fact that no such figures appear amongst the damned.

_1467_71.jpg)

_Two_1467_71.jpg)

_Three_1467_71.jpg)

_Four_1467_71.jpg)

_Five_1467_71.jpg)

The rainbow separates the two worlds and their different orders; the ethereal golden space of God's Kingdom appears at the top, while the earth, represented as a wide plain bordered in the distance by a chain of mountains, is shown at the bottom. This will be the valley of Josaphat, which, according to the apocryphal authors (Honorius of Autun, James of Voragine) would be the site of the Last Judgment. The time of day is fixed by the dark blue-green night sky.

The figure of Saint Michael stands on the earth directly below Christ, on the dividing line between the green soil to the left and the barren brown plain to the right. Holding the scales in his right hand, he uses the crosier in his left to prick the flesh of the damned soul, as if to prod him towards the mouth of hell.

_Six_1467_71.jpg)

_Seven_1467_71.jpg)

_Eight_1467_71.jpg)

The man in the scale is a portrait, his features closely resembling those of Tommaso Portinari. This head is an early addition (identified as such as far back as 1781).

The care and planning expended not only on the composition, but also on the representation of natural phenomena like foreshortening, light and reflection, are striking, as in the rest of Memling's oeuvre. Saint Michael's curved breastplate and the globe reflect the unfolding events with hallucinatory precision (only here do we see clearly how the Romanesque towers loom up behind the Gothic heavenly gates). The size of the figures reduces dizzyingly depending on how close or distant they are. The colours of the rainbow are accurately reproduced.

_Nine_1467_71.jpg)

_Ten_1467_71.jpg)

_Eleven_1467_71.jpg)

_Twelve_1467_71.jpg)

_Thirteen_1467_71.jpg)

_Fourteen_1467_71.jpg)

_Fifteen_1467_71.jpg)

_Sixteen_1467_71.jpg)

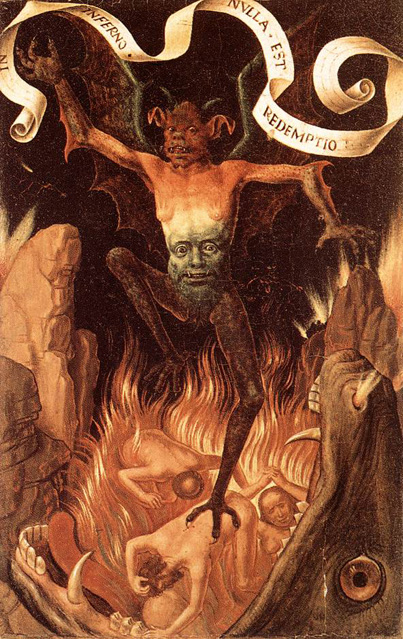

Before departing for London in December 1467, Tani founded a chapel dedicated to Saint Michael at his employer's church in Fiesole and drew up his will. He probably also made funeral arrangements in the customary manner. He will then have required an altarpiece, which he ordered from Memling some time after the end of 1467 during his stay in the north. The painting was, therefore, largely executed during his stay in London between 1467 and 1469, from where he could monitor its progress. The iconography of the altarpiece is clarified by its destination. Saint Michael has been selected here first and foremost as the saint to whom the chapel was dedicated, and only in the second place as Tani's patron. This also explains the absence of the woman's patron. Taken together, the grisailles depict the victory of St Michael over Satan, who was threatening the Virgin and Christ Child.

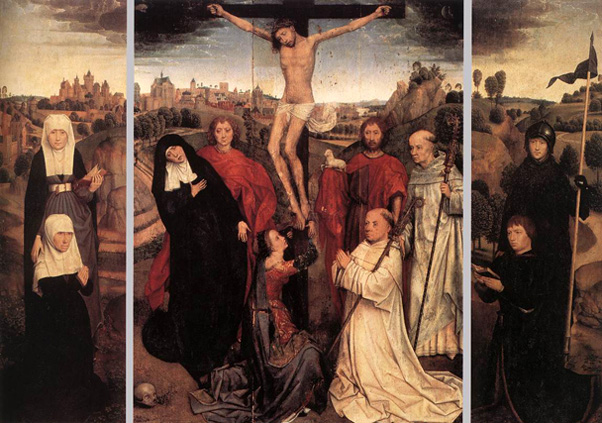

It is characteristic that the oldest allusions to pictures connected with Memlinc's name are those which point to relations with the Burgundian court. The inventories of Margaret of Austria, drawn up in 1524, allude to a triptych of the God of Pity by Rogier van der Weyden, of which the wings containing angels were by "Master Hans." But this entry is less important as affording testimony in favor of the preservation of Memlinc's work than as showing his connection with an older Flemish craftsman. For ages Rogier van der Weyden was acknowledged as an artist of the school of Bruges, until records of undisputed authenticity demonstrated that he was bred at Tournai and settled at Brussels. Nothing seems more natural than the conjunction of his name with that of Memlinc as the author of an altarpiece, since, though Memlinc's youth remains obscure, it is clear from the style of his manhood that he was taught in the painting-room of Van der Weyden. Nor is it beyond the limits of probability that it was Van der Weyden who received commissions at a distance from Brussels, and first took his pupil to Bruges, where he afterwards dwelt. The clearest evidence of the connection of the two masters is that afforded by pictures, particularly an altarpiece, which has alternately been assigned to each of them, and which may possibly be due to, their joint labors. In this altarpiece, which is a triptych ordered for a patron of the house of Sforza, we find the style of Van der Weyden in the central panel of the Crucifixion, and that of Memlinc in the episodes on the wings. Yet the whole piece was assigned to the former in the Zambeccari collection at Bologna, whilst it was attributed to the latter at the Middleton sale in London in 1872. At first, we may think, a closer resemblance might be traced between the two artists than that disclosed in later works of Memlinc, but the delicate organization of the younger painter, perhaps also a milder appreciation" of the duties of a Christian artist, may have led Memlinc to realize a sweet and perfect ideal, without losing, on that account, the feeling of his master. He certainly exchanged the asceticism of Van der Weyden for a sentiment of less energetic concentration. He softened his teacher's asperities and bitter hardness of expression.

In the oldest form in which Memlinc's style is displayed, or rather in that example which represents the Baptist in the gallery of Munich, we are supposed to contemplate an effort of the year 1470. The finish of this piece is scarcely surpassed, though the subject is more important, by that of the Last Judgment of Danzig.

Senex Magister

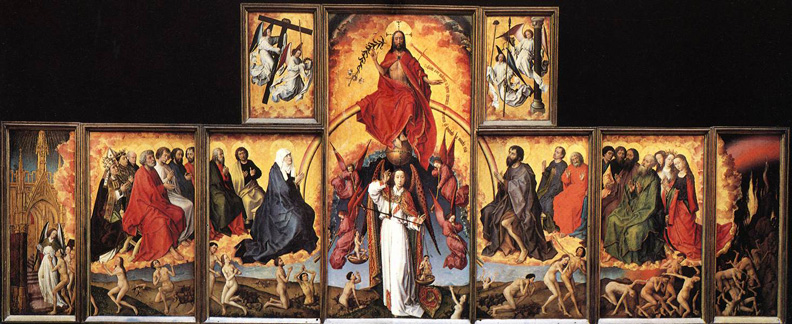

The enormous polyptych is made up of fifteen panels of different sizes. It was painted by Rogier Van der Weyden and his studio for the "great hall of the poor" in the Hôtel-Dieu in Beaune. This hospital was founded by the fabulously wealthy Chancellor Rolin, and his devout third wife, Guigonne de Salins, for the salvation of their souls and in the hope of storing up treasures in heaven. Work began in 1443. The room was a vast open nave, with a paneled barrel vault for a ceiling, and could contain thirty canopied beds along its two long walls. The polyptych was placed at one end of this space, behind the altar, in a chapel separated from the nave by an "open-work wooden partition", through which patients could follow the divine service from their sick beds.

As long as the polyptych hung in the chapel, it was traditional to open the wings on Sundays and solemn feast days. But since it has been restored, it is now kept in a neighboring room which is air-conditioned to prevent any further deterioration due to the heat generated by the three hundred thousand visitors who come to see it each year. The panels were sawn in half across the thickness of the wood a few years ago, and both front and the reverse are now exhibited simultaneously, side by side.

On either side of the central figures of Christ and the Archangel Michael, the composition is built up on two levels. Above is a cloud of gold, on which are seated the apostles, judges in the celestial tribunal, as well as a pope, a bishop, a king, a monk and three women. Below them is the earth, from which the resurrected souls emerge, to go either to damnation or to eternal bliss. The central panel is dominated by the son of God, seated on a semi-circular rainbow; with the Virgin Mary at one end of the arc and Saint John the Baptist at the other. Christ's feet rest on a sphere, symbol of the universe. With his right hand, he blesses those who are saved and with his left curses those who are damned. These two gestures are emphasized by appropriate emblems, respectively, a lily and a blazing sword. Beneath Christ stands Saint Michael, prince of the heavenly hosts. He is pictured as young, because he is immortal and as handsome, because he is the embodiment of divine justice. He holds in his hands a scale in which he weighs souls. The souls are represented by two little naked figures, whose names are "Virtues" and "Peccata". The former kneels, overcome with delight, while the latter seems horrified and screams with terror.

The lower tier depicts the elect and the damned. They are represented by two small groups of figures. They too are naked and are portrayed on a smaller, more human scale, than the saints above them. We see them propelled inexorably towards their fate. The damned are crushed beneath the weight of their sins. They have themselves painfully up out of the cracked dry earth, surrounded by sparks of fire and wisps of smoke. In contrast, on the opposite side of the polyptych, as one approaches paradise, flowers grow more and more abundant. In Van der Weyden's time, woman was regarded as a temptress and it was therefore more difficult for her to be saved than for a man - hence there are only two women in the group which, lead by an angel, are about to ascend to heaven. It was also believed that lunatics were possessed by demons. Here, the figures of the damned are tortured and deformed by hatred and their faces distorted by madness. Gripped by a collective hysteria, they are unable to weep, but instead scream and fight, as their folly draws them on towards eternal punishment. At the far left-hand side of the polyptych, paradise is represented as a gothic porch ablaze with light, the door that leads to the divine dwelling place. On the other side, hell is strangely lacking in devils. Instead, it is merely represented by a pile of dark rocks spewing flames and volcanic vapors.

But the latter is more interesting than the former, because it tells how Memlinc, long after Rogier's death and his own settlement at Bruges, preserved the traditions of sacred art which had been applied in the first part of the century by Rogier van der Weyden to the Last Judgment of Beaune. All that Memlinc did was to purge his master's manner of excessive stringency, and add to his other qualities a velvet softness of pigment, a delicate transparence of colors, and yielding grace of slender forms. That such a beautiful work as the Last Judgment of Danzig should have been bought for the Italian market is not surprising when we recollect that picture-fanciers in that country were familiar with the beauties of Memlinc's compositions, as shown in the preference given to them by such purchasers as Cardinal Grimari and Cardinal Bembo at Venice, and the heads of the house of Medici at Florence. But Memlinc's reputation was not confined to Italy or Flanders. The Madonna and Saints which passed out of the Duchatel collection into the gallery of the Louvre, the Virgin and Child painted for Sir John Donne and now at Chatsworth, and other noble specimens in English and Continental private houses, show that his work was as widely known and appreciated as it could be in the state of civilization of the 16th century. It was perhaps not their sole attraction that they gave the most tender and delicate possible impersonations of the Mother of Christ that could suit the taste of that age in any European country. But the portraits of the donors, with which they were mostly combined, were more characteristic, and probably more remarkable as likenesses, than any that Memlinc's contemporaries could produce. Nor is it unreasonable to think that his success as a portrait painter, which is manifested in isolated busts as well as in altarpieces, was of a kind to react with effect on the Venetian school, which undoubtedly was affected by the partiality of Antonello da Messina for trans-Alpine types studied in Flanders in Memlinc's time. The portraits of Sir John Donne and his Wife and Children in the Chatsworth Altarpiece are not less remarkable as models of drawing and finish than as refined presentations of persons of distinction; nor is any difference in this respect to be found in the splendid groups of father, mother, and children which fill the noble altarpiece of the Louvre. As single portraits, the busts of Burgomaster Moreel and his Wife in the museum of Brussels and their daughter the Sibyl Zambetha (according to the added description) in the hospital at Bruges, are the finest and most interesting of specimens. The Seven Griefs of Mary in the gallery of Turin, to which we may add the Seven Joys of Mary in the Pinakothek of Munich, are illustrations of the habit which clung to the art of Flanders of representing a cycle of subjects on the different planes of a single picture, where a wide expanse of ground is covered with incidents from the Passion in the form common to the action of sacred plays.

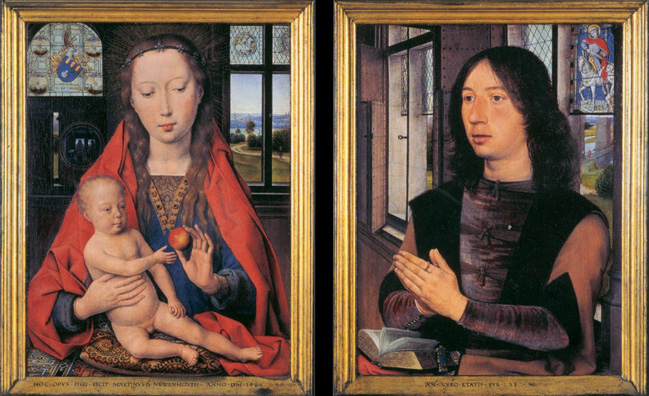

The masterpiece of Memlinc's later years, a shrine containing relics of Saint Ursula in the museum of the hospital of Bruges, is fairly supposed to have been ordered and finished in 1480. The delicacy of finish in its miniature figures, the variety of its landscapes and costume, the marvelous patience with which its details are given, are all matters of enjoyment to the spectator. There is later work of the master in the Saint Christopher and Saints of 1484 in the academy, or the Newenhoven Madonna in the hospital of Bruges, or a large Crucifixion, with scenes from the Passion, of 1491 in the Cathedral of Lubeck. But as we near the close of Memlinc's career we observe that his practice has become larger than he can compass alone; and, as usual in such cases, the labor of disciples is substituted for his own. The registers of the painter's corporation at Bruges give the names of two apprentices who served their time with Memlinc and paid dues on admission to the gild in 1480 and 1486.

Source: Entry on the artist in the 1911 Edition Encyclopedia.

From: Art Renewal Center

This is the most Rogierian Virgin ever done by Memling. The taut drawing and curved outlines within the compact triangle formed by the Virgin's head and hands and the Child do not appear in any other Memling work, except for copies after Van der Weyden, like the Brussels Virgin and Child. It is doubtful whether this too is a copy, however, as no other versions of the type exist. The overall composition is, in fact, a kind of adapted synthesis of the most famous Rogierian devices. The view between two columns, the crenellated wall and the perspective of the buildings on the left and right come from Saint Luke Painting the Virgin, the arch motif from the Miraflores altarpiece and the little dark blue angels from the Vienna Crucifixion. Memling's own vision is apparent even at this early stage in the calm, frontal position of the Virgin on her metal throne, accompanied symmetrically by musical angels. The golden sky is an interestingly archaic element that we rarely encounter even in Van der Weyden (Philadelphia Crucifixion, Frankfurt Medici Virgin). An oriental carpet is not used here either, and the Virgin sits instead on a simple, dark green floor-covering.

The triptych had been commissioned by Jan Crabbe, twenty-sixth abbot of Ter Duinen Abbey in Koksijde (1457-1488), to mark the occasion of his fifteenth anniversary as prelate in 1472. The other figures in the painting were identified as his mother Anna and his brother Willem. This identification is highly plausible in chronological terms as far as Jan Crabbe is concerned. Crabbe was the only Flemish Cistercian abbot with the first name Jan in Memling's time. The praying abbot here is indeed a Cistercian, and is protected by both Saint John the Baptist and Saint Bernard.

The Annunciation is one of the earliest examples in the Low Countries of a `natural' or `living' grisaille with figures whose bodies are 'colored'.

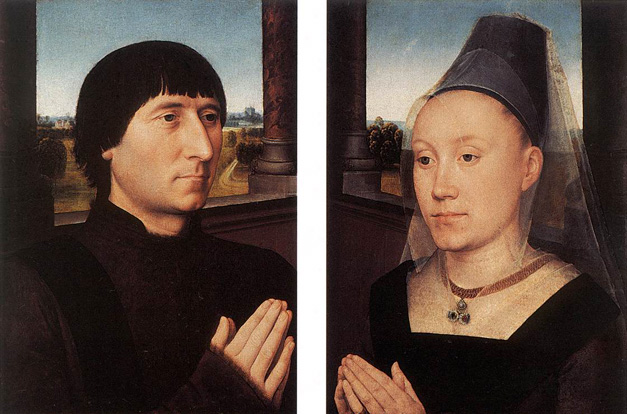

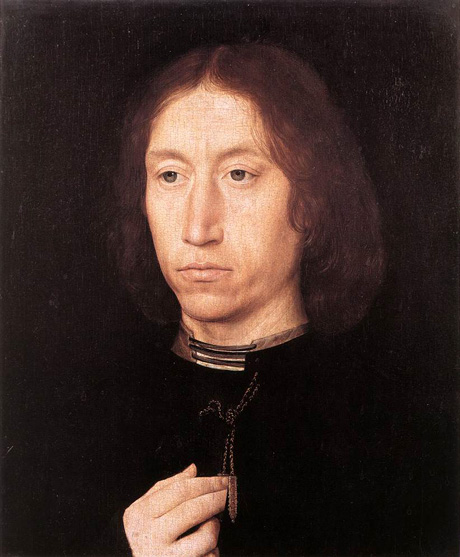

Memling's work was particularly popular with members of the large Italian community in Bruges. Tommaso Portinari, a Florentine who represented the Medici bank in Bruges, married Maria Baroncelli in 1470, when he was 38 and she was 14. It was soon after their marriage that Portinari commissioned this exquisite pair of portraits of himself and his wife, which must have originally been the wings of a triptych. Portinari, who loved Flemish art, also commissioned Hugo van der Goes to paint the famous Portinari Altarpiece (now in the Uffizi, Florence).

The triptych depicts the Nativity (left), the Adoration of the Magi (central) and the Presentation of the Temple (right).

The viewpoint is very high, as a result of which Calvary is visible above the city and a virtual bird's eye-view is given of the buildings at the bottom. Although consistent one-point perspective is rendered impossible by the varied position of the different buildings, the viewer retains a sense of perspective unity and logic, from the foreground to the level of the towers, which are ranged squarely across the horizon. In addition to perspective unity, there is also a spatial unity in the treatment of the scenes and unity of lighting. The latter, in particular, is a rare tour de force in the painting of the period, because the light source is located within the painting and is associated visually with the rising sun on the far right, so that the area located diagonally before it in the front left remains in shadow. Only the donors, who kneel in the corners before the entire spectacle, appear to be immune from this effect. The right-hand part of the architecture, down to a stretch of the crenellated wall at the front, has a pink glow and we see the first, still low rays of the sun reaching the brick gates in the left distance.

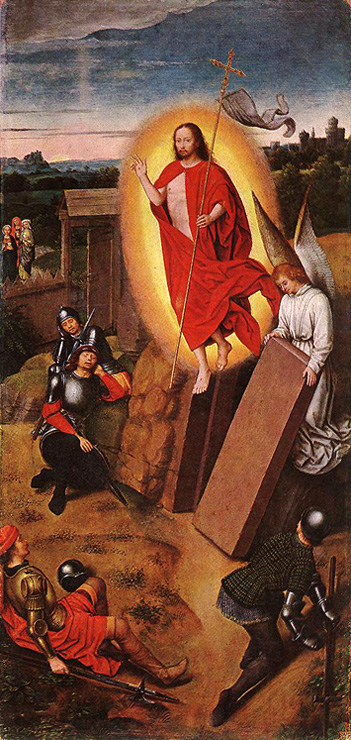

The Passion cycle is enacted in this setting with the addition of the Resurrection and several of Christ's appearances to his followers, but without the Ascension. This is the first time that Memling applied the spatial narrative structure that he was later to use on two other occasions (Munich and Lübeck) to present a Gospel cycle. The narrative meanders symmetrically from the rear left to the foreground and through the principal scene in the middle, before culminating on the right, once again in the distance. Calvary is set somewhat apart as the principal scene in the background. Christ's various appearances after his Resurrection are not particularly significant in iconographical terms, and are probably included as visual links running into the landscape. The painting enabled believers to visit the Holy Places in and around Jerusalem in their imagination. It is a kind of spiritual model of the crusaders' journey.

The donors have been identified as Tommaso Portinari, a Florentine banker in Bruges, and his wife Maria Baroncelli on the grounds of their resemblance to bust portraits of the couple painted by Memling.

It is generally accepted that the painting should be ascribed to Memling and dated to around 1470. The figures do indeed retain the rather stocky frame and rounded physiognomy of the earliest works. Mary is identical to the Ottawa Virgin, which dates from 1472. The little painting also closely resembles the Nativity in the left wing of the Prado triptych in terms of style. A date of around 1470-72 would thus appear likely.

The painting, in all probability, has been the central panel of a small triptych with donor wings on either side, or possibly an iconography that was also inspired by the Bladelin triptych. It must have been located in or around Bruges, because it was copied towards the end of the fifteenth century in a small tondo located in Saint John's Hospital in Damme.

The painting is in its original frame.

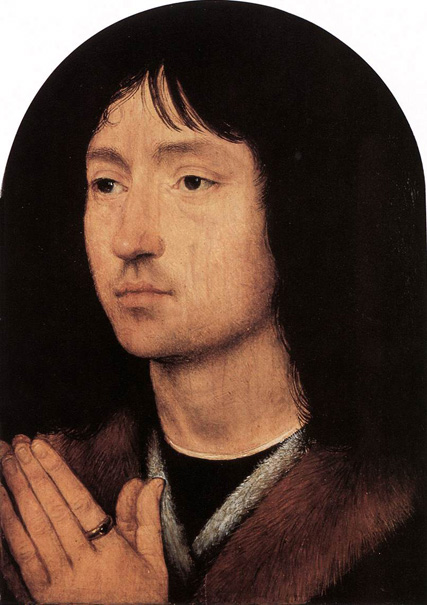

This is the earliest dated portrait by Memling and serves as a crucial milestone for the dating of other portraits from this period, including the Moreel portraits and the donors in the Last Judgment [Gdansk]. The modeling of all these portraits is highly simplified and all the subjects have long, tapering fingers with oval nails.

The subject was positively identified as Gilles Joye (1424-1483) on the basis of an old inscription on the reverse and the coat-of-arms. Joye began his career as a canon in the chapter of Our Lady in Cleves (1453-1460), before taking a similar position at Saint Donatian's in Bruges (after 1463). He later became pastor at the Oude Kerk in Delft (1465- 1469), after which he was made clerk and Kapellmeister of Philip the Good (1462- 1469). He enjoyed some fame as a composer and settled in Bruges in the early 1450's.

It is unlikely that the portrait ever belonged to a diptych, because there are no traces of hinges on the still intact frame (although this was assumed to be the case by some scholars). This hypothesis is strengthened by the fact that the sitter's coat-of-arms appears on the front and not on the reverse. The painting will ultimately have been commissioned to adorn his tomb in the sacristy of St Donatian's Church, during a period of his life when he was afflicted by illness. Perhaps the portrait was installed there immediately.

The companion-piece of the painting, Portrait of an Old Man, is in the Staatliche Museen, Berlin.

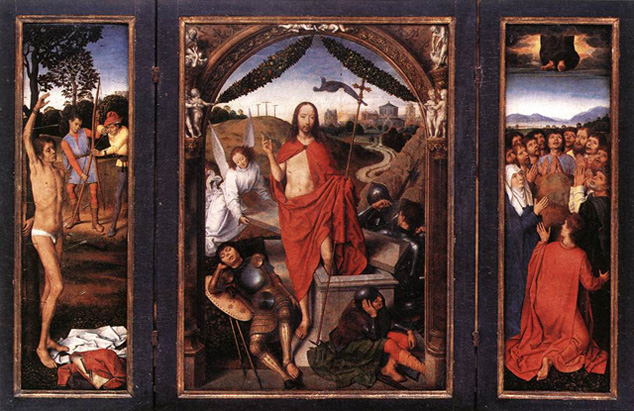

Sebastian, a young captain of the Praetorian Guard, assisted Christians during Diocletian's persecutions at the end of the third century. Unmasked, he refused to abjure his faith and was handed over to archers on the Field of Mars in Rome. Left for dead, he survived thanks to the care of a widow called Irene. When subsequently he returned to the imperial palace to protest against the cruel treatment reserved for the Christians, he was again arrested and put to death in the Coliseum.

In this high quality painting, Hans Memling concentrates on Sebastian's first confrontation with his executioners. The action takes place in a raised site, dominating a vast landscape of a port city surrounded by a medieval wall. To the right one archer has just shot his arrow, whilst the second is stretching his bow. Behind them, half hidden between two rocks, Emperor Diocletian is giving the order to execute the sentence. To the left Sebastian, chest bared, is attached to a tree, his shirt and rich brocade mantle cast at his feet. Five arrows pierce him. Despite his martyrdom, no sign of suffering marks the saint's features. This sign of the triumph of faith is typical of Memling, looking for suavity of forms. Added to this, his fine sense of detail and rendering of materials, particularly well represented by the magnificent brocade of the mantle in the foreground, place him among the great Flemish painters of the 15th century.

The arrow being the symbol of the plague, Sebastian, who survived his martyrdom, became the protector par excellence against this sickness. The saint's pose, with the right arm along his body and his left arm attached to the tree above his head, can also be related to German engravings accompanying prayers against the plague. In addition, the arrows which pierce his four limbs and his side make reference to the five wounds of the crucified Christ.

The man and woman, represented in half bust, face each other in an attitude of prayer. Both are positioned in a gallery opening onto a wide landscape. The man is wearing a purplish garment trimmed with fur under which a black doublet with a rising collar is to be seen. A black 'cornette' is hanging from his right shoulder. The woman wears a purplish dress with a low V-shaped neckline, edged with a black border typical for the 1470/80's. Around her neck she wears a transparent linen veil or 'gorgerette'. Above her drawn-back hair, her short truncated 'hennin' is covered with a fine veil which falls down over her shoulders. Her necklace consisting of a double row of chain-links is decorated with a pendant containing a pearl and two precious stones. On her left little finger she wears two rings. The top of a golden belt buckle is also visible, just under her chest.

The sitters are identified by their coats of arms and inscriptions on the back of the two panels as Willem Moreel and his wife Barbara van Vlaenderberch, alias de Herstvelde. Willem Moreel, Lord of Oostcleyhem, was one of the richest citizens of Bruges where he was a spice trader. He was also a banker for the Bruges branch of the Banco di Roma. Between 1472 and 1489 he was successively a counselor, then burgomaster, bailiff and treasurer of the city. He had five sons and thirteen daughters from Barbara van Vlaenderberch. In 1484 the couple also commissioned Hans Memling to paint a large altarpiece (Bruges, Groeningemuseum) for their chapel in the Bruges church of Saint James, on the side panels of which their entire family is represented.

Originally these two portraits were part of a triptych, of a type intended for meditation and private devotion, the central element of which was a religious subject, probably here a Virgin and Child. The painting probably folded flat and had three equally sized panels. The man's coat-of-arms is featured on the rear of the woman's portrait, and will thus have been visible on the outside of the closed case. The exchange of escutcheons will, however, have been intended primarily as a kind of eternal link between the two portraits. Memling applied a similar procedure to the wings of the Last Judgment.

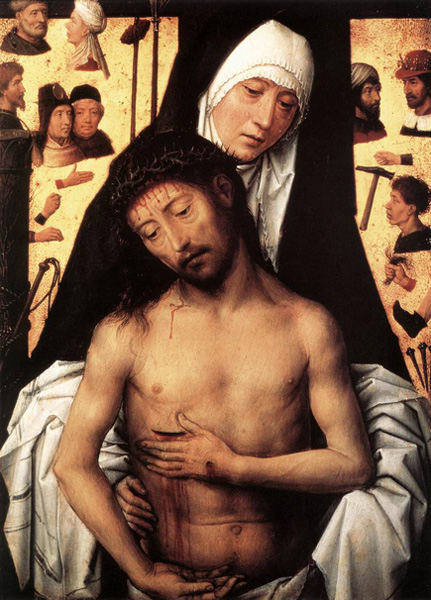

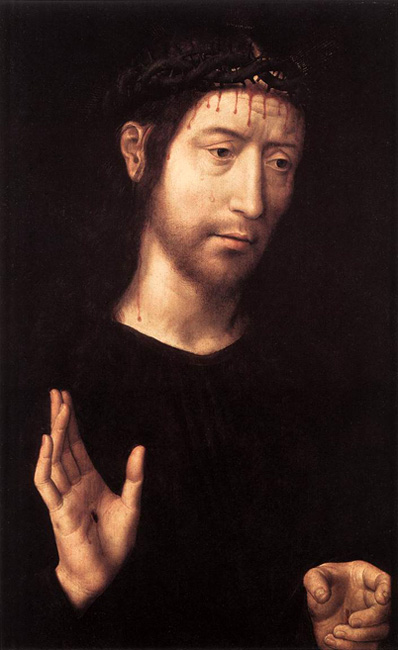

Apart from a few copies, there is one larger version that is worthy of particular note (Granada, Capilla Real). This might be a copy of a second version of the same theme, also designed by Memling. A third Memling Man of Sorrows is also known, in which the figure of Christ makes the same gesture with his right arm as the Granada type.

It is assumed that the painting belonged to a triptych. It has been established with near certainty that the Angel with a sword in London's Wallace Collection is the right wing of this triptych, and that the recently discovered Angel with an olive branch in the Louvre is a fragment of the left wing.

The date on the column capital is no longer clearly legible. The last numeral is particularly badly abraded, which gave rise to a variety of readings in the past.

Attempts have been made to link the donor figure with that in the Bucharest wing and to identify it as the perfect likeness of Willem Moreel. The man in Bucharest certainly cannot be Willem Moreel, because his wife does not resemble Barbara van Vlaenderberch and only one son is present. If the donor in Rome is, indeed, the same as the one in Bucharest, then he must be younger in the Rome painting (no wife or child) - a point which does not conflict with his features.

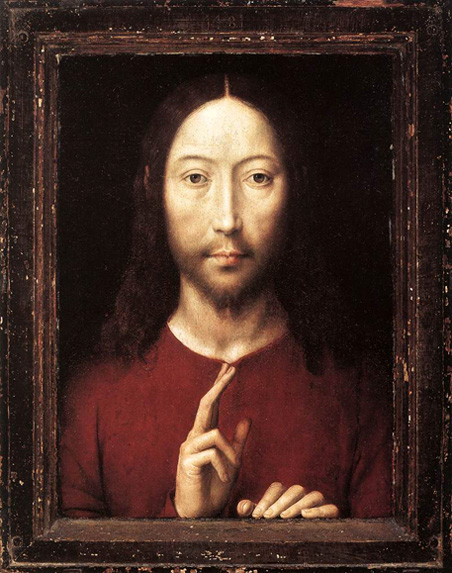

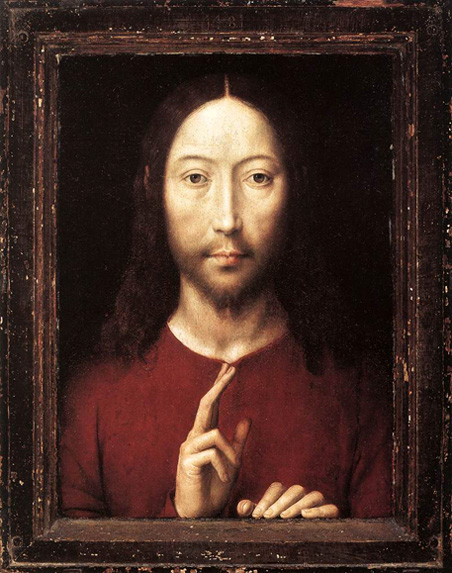

The immediate typological precursor of this presentation is the Master of Flémalle's 'Salvator Mundi' (Philadelphia, John G. Johnson Collection) in which the fingers of the left hand are also just visible above the edge. Christ himself, the form of his robe and the position of the hand with which he gives his blessing are a development on the Jean de Braque Triptych by Rogier van der Weyden. Although created at a much earlier date and less robust and more transparent in its execution, the Pasadena version is readily comparable with Memling's Christ with musical angels in Antwerp. The rounded, almost sculptural features, the softly flowing hair of the beard and moustache, the fingers with their round tips in almost the same position of blessing, are all very similar. The under drawing of the Pasadena work reveals that the hand making the blessing was designed on the panel itself. Several of its contours do not match the painted form at all, and the latter was itself corrected several times, even after the dark brown color of the robe had already been painted around the fingers. The ring and little finger were originally drawn closer together, and the forefinger and index finger were more bent. Christ's hand in Antwerp is more or less the finished result of the Pasadena version, though in a more elongated form.

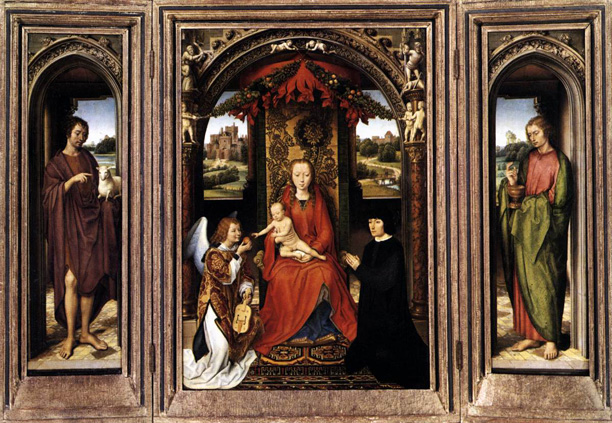

The central panel focuses upon a Sacra Conversazione, a gathering of saints around the Virgin. However, the narrow vertical openings between the columns reveal a continuous landscape with ruins and buildings in which small episodes from the lives of the two male saints are enacted. The two wings each depict episodes from the lives of the standing figures of the Two Saint Johns on either side of the Virgin. The left wing features the 'Beheading of Saint John the Baptist' and the right wing 'Saint John the Evangelist on the Island of Patmos'. In addition to these realistic portrayals, the carved groups on the two capitals above each saint also depict key moments from their lives.

The composition of the Triptych as a whole is not only ingenious in narrative terms, with the different components interlocking spatially and thematically; it is also new in many respects as far as the portrayal of the Virgin Mary in heaven and the Apocalypse are concerned. The iconographical forebears of such a grouping of saints sitting and standing around an Enthroned Virgin are few and far between. The only extant examples are, in fact, the Virgo inter Virgines from the circle of the Master of Flémalle in Washington and a similar composition, this time set in a room, by Rogier van der Weyden, several fragments of which have survive. They are not, however, comparable in formal terms. This clear monumental composition, with two symmetrical standing male saints and two sitting female saints, forming a tetramorph around the Virgin, must have seemed very new. As is the case with the architecture, Memling appears to have developed here upon Jan van Eyck's Virgin with Canon van der Paele. The Apocalypse is new too. There is no sign of any other representation prior to Memling in which the Book of Revelation is played out before Saint John's eyes in its entirety in a single, undivided painting. Only in the Beheading of Saint John the Baptist did Memling prefer to paraphrase a Van der Weyden composition (Saint John altarpiece, Berlin, Staatliche Museen). However, the stylized terseness and enclosed character of the latter give way here to dramatic action in the open air, with a high degree of realism.

In view of the historical circumstances and iconography, there can be no doubt whatsoever that this Triptych was painted for the High Altar of the chapel of Saint John's Hospital. An old inscription on the bottom member of the frame gives the date 1479 and the name of the artist Johannes Memling. With the exception of the Floreins triptych in the same hospital, this is the only work by Memling to be authenticated by an original (in this case subsequently over painted) inscription. The donors were also identified. Jacob de Ceuninc was initially recorded as a monk at the hospital in 1469-70, and later as bursar from 1488 until his death in 1490. Antheunis Seghers was first mentioned in 1455-56 and appears to have been master from 1461 to 1465, bursar from 1466 to 1468, and then master again from 1469 until his death in 1475. Agnes Casembrood was first recorded in 1445-46, and subsequently appears as prioress from 1459 to 1463, and again from 1469 until her death in 1489. Clara van Hulsen makes her initial appearance in the records in 1427-1428, and died in 1479. Given that these are evidently intended as portraits, the altarpiece must have been ordered before the death of Antheunis Seghers in 1475, which means that its production may logically be linked with the expansion of the chapel's apse in 1473- 74 though we lack details of Jacob de Ceuninc and Clara van Hulsen in those years.

The altarpiece is, of course, dedicated to the patron saints of Saint John's Hospital. The central portrayal of the Virgin might relate to the hospital chapel's long-standing and close links with the chapter of the almost adjacent Church of Our Lady. The two female Saints, Catherine and Barbara, were frequently invoked in adversity. Their presence in the hospital context has frequently been explained in terms of their symbolizing respectively the contemplative and active life of the hospital's monastic community.

_1474_79.jpg)

The scenes in the Triptych dealing with Saint John the Baptist are the following (in chronological order).

The first capital above the Baptist's head (central panel) represents the announcement of his birth to Zacharias. The birth itself is shown in the second capital. His life story commences in the far left background of the central panel, before meandering across the left wing and back into the middle. The evangelical episodes comprise a synthesis of all four Gospels, although some derive solely from the Gospel of Saint John. From rear to front in the central panel, we see Saint John the Baptist praying in the wilderness (the forest) and the Sermon. In the left wing, from left to right: Saint John the Baptist answering the questions of the priests and Levites, the Baptism of Christ and the Ecce Agnus Dei enacted before John's first two disciples on the opposite bank of the Jordan. The Arrest of Saint John the Baptist by Herod is once again portrayed in the central panel. John is led away to the left towards the prison tower in the left wing, opposite which Salome's dance takes place in an open chamber of the palace. Sculpted figures in niches above this scene represent a naked man between two naked women. We are meant to understand these as pagan images, possibly alluding to Herod's immoral behavior.

The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist in the foreground takes place on the high, barren execution yard of the prison, which is reached by a staircase from the courtyard of the palace. The two disciples of John the Baptist, Andrew and Saint John the Apostle, are seen standing to the right of this courtyard. Behind and to the right of the figure of the Baptist in the central panel, his body is exhumed at the command of Emperor Julian the Apostate in Sebaste, and burned. His semi-decomposed head, which according to legend was hidden by Herodias, or buried separately by the apostles, can be seen in an opening in the wall, behind a stone that has been pushed aside.

_1474_79.jpg)

_Two_1474_79.jpg)

_Three_1474_79.jpg)

_Four_1474_79.jpg)

_Five_1474_79.jpg)

The standing figures of the Two Saint Johns on either side of the Virgin in the middle ground personify aspects of the Eucharist. Saint John the Baptist with the lamb at his side points with his right hand to the incarnated Jesus, the true sacrificial Lamb, who holds an apple in his hand to indicate that he is the new Adam. Saint John the Evangelist blesses his poisoned chalice in the manner of the priest during Mass. The sacral nature of the scene heightens the significance of the book held up to the Virgin by the angel kneeling like an acolyte on the right, and the music played by the angel with the portative organ on the left. Mary functions as a kind of divine, consecratory altar. The overall scene is thus a vision of the Eucharist. The composition of the group is perfectly symmetrical, as is the architectural construction to the rear that encloses them. It is a kind of apse, with an ambulatory, without walls or windows.

Memling was doubtlessly influenced by the architecture in Jan van Eyck's Virgin with Canon van der Paele, which he opened up and elongated to form a series of light columns, thus taking the setting a stage further. Six brownish-red, round marble columns stand in a semi-circle on a tile floor. They are surrounded by a second crescent of dark-grey composite piers, whose bases are linked by the straight edges of the floor, which thus forms a polygonal footing for the architecture. A simplified version of this construction is to be found in Memling's Granada Virgin. The floor-pattern is repeated several times in his work. Allowing for the aberrations arising from manual execution, the perspective is systematic and geometrically correct. The narrow vertical openings between the columns reveal a continuous landscape with ruins and buildings in which small episodes from the lives of the two male saints are enacted. The two wings each depict one such incident in enlarged form in the foreground. In addition to these realistic portrayals, the carved groups on the two capitals above each saint also depict key moments from their lives. The scenes connected with the altarpiece's principal figures are not, however, the only action going on in the landscape. There is a third background scene which, though interwoven spatially with the others, actually relates to the donors, namely the clerics of Saint John's Hospital in Bruges. It depicts the measuring of imported wine at the city crane by a monk from the hospital (behind Saint John the Baptist), and another monk on the far right, half obscured by a column. This striking and detailed little figure was once taken erroneously for a self-portrait of the artist. However, close examination reveals his features to be those of Jacob de Ceuninc. Saint John's Church, which no longer exists, can be made out next to the column to the right of the wooden crane, from where it could be seen. It forms yet another allusion to the Saint John theme.

_Six_1474_79.jpg)

_Seven_1474_79.jpg)

_Eight_1474_79.jpg)

_Nine_1474_79.jpg)

_Ten_1474_79.jpg)

The scenes in the Triptych dealing with Saint John the Evangelist are the following (in chronological order).

Memling intended to dedicate the entire Right Wing to the apocalyptic vision of Saint John the Evangelist, which meant that there was hardly any space left in the Central Panel to depict episodes from the life of the saint chronologically. The small scenes are thus shown one above the other, in no particular order.

According to his legend, Saint John was first immersed in boiling oil and then banished to the island of Patmos (we see him embarking on the boat). Upon his return to Ephesus, he raised Drusiana from the dead (first capital), baptized the converted philosopher Crato (in the domed building at the very back) and drank unharmed from the poisoned chalice (second capital). These scenes are given a Roman setting with the Coliseum in the background.

The vision of the Revelation or Apocalypse is presented in the Right Wing with a spatial and dynamic unity that precisely follows the key moments of the text. Banished to the island of Patmos in the Aegean Sea, Saint John sits with a book on his lap, and dips a pen into an ink-pot, his pen-knife at the ready. He stares upwards, where his visions take shape in the air, on the water and on the adjoining land, in what was for its time a new and unique total spectacle. God appears beneath a stone canopy supported by columns, wearing a red and green robe. He has a greenish glow about his face and hands and is surrounded by a rainbow. Seven lamps burn around the canopy and flames shoot from the rainbow. The twenty-four elders (only thirteen of whom are visible) are seated around the throne wearing golden crowns and dressed in white robes. The throne stands on a crystal surface in which everything is reflected. God is accompanied by four beasts covered with eyes and with six wings: one like a lion, one like an ox, one like a man and one like an eagle. The vision of heaven as a whole is enclosed in a second circular rainbow.

The subsequent vision of the Lamb and the sealed book is incorporated in the first. God's right hand rests on a book with seven seals. An angel at the front of the scene points to it and addresses John. A lamb with seven horns and eyes holds the book between its front paws. Memling took another detail - 'Each of the elders had a harp. .. and they were singing a new song' (Rev. 5:8-9) - and adjusted it slightly, giving them a variety of musical instruments. The Lamb then breaks six seals, one after the other, causing the four horsemen to appear arid unleashing cosmic disasters. The sequence of the horsemen, each on a little island, reads from left to right: a white rider with a crown on a white horse who looses off an arrow to his rear; a knight in black armor armed with a sword on a light brown horse (the text refers to a red horse); a figure with a long robe on a black horse, carrying a pair of scales; and a pale brown horse ridden by Death, followed by a burning monster's head, in whose mouth human bodies shrivel. Memling did not include the breaking of the fifth seal. The breaking of the sixth seal causes an eclipse of the sun and the stars to fall from the sky. Rich and poor flee into caves. The natural phenomena can be witnessed high above in the sky, while to Death's right we see the figures of a slave, a king and a freeman hiding in rocky crags. When the seventh seal is broken, seven angels are given seven trumpets. Memling included this episode at the top of the circular rainbow. The trumpets are handed out by an arm that emerges from behind a cloud in the topmost corner. Another angel kneels before an altar at the bottom of this mandorla. He spreads incense from a golden censer towards the figure of God. Glowing coals lie on the altar, which he will shortly throw to the earth, causing peals of thunder and earthquakes.

Memling also included the following events, each announced by one of the trumpets, in a series of increasingly distant and small scenes: hail and fire rain upon the land, and the grass burns, the burning mountain is hurled into the sea and destroys the ships, and a star falls like a torch from the heavens into the rivers and springs, poisoning them. The latter can be seen on the right-hand edge. A corpse lies alongside a rectangular well. An eagle soars high in the sky. The peninsula to the right features the star with the key of the shaft of the abyss, from which smoke rises and locusts emerge in the form of winged horses with crowned human heads, women's hair, lions' teeth, scorpions' tails and iron breastplates. One of the horses is ridden by a black, demonic figure with the fool's crown. This is Abaddon, the angel of the abyss. A group of cavalrymen wreak death and destruction opposite. The soldiers wear red and grey armor, and ride animals with fire-breathing lions' heads and tails with serpents' heads. They are led by four angels in armor who stand on the bank. Behind them appears a gigantic angel, one foot on the water, the other on the land, his legs like fire, his body wrapped in cloud, his face as yellow as the sun, with a rainbow above his head and a small book in his hand. Memling also followed the biblical text word-for-word for the remainder of the portrayal: the seven thunders are represented as explosions above the angel, who lifts his right arm to heaven to hand over John's book, while the author stands a small distance away, his hands raised. The final scenes relate to the Woman and the Dragon and the creation of the blasphemous Beast. The Virgin Mary appears high in the sky, holding her Child beyond the reach of the red, seven-headed dragon. The latter's tail sweeps the stars from the heavens (the same falling stars from previous disasters in Memling's portrayal). The Dragon is vanquished by Michael to the right, and below pursues Mary, who now has wings. Finally, on the horizon of the sea, the Dragon confers its authority on a seven-headed beast with the body of a leopard that rises from the waters.

_Eleven_1474_79.jpg)

_Twelve_1474_79.jpg)

_1474_79.jpg)

The donors were identified. Jacob de Ceuninc was initially recorded as a monk at the hospital in 1469-70, and later as bursar from 1488 until his death in 1490. Antheunis Seghers was first mentioned in 1455-56 and appears to have been master from 1461 to 1465, bursar from 1466 to 1468, and then master again from 1469 until his death in 1475. Agnes Casembrood was first recorded in 1445-46, and subsequently appears as prioress from 1459 to 1463, and again from 1469 until her death in 1489. Clara van Hulsen makes her initial appearance in the records in 1427-1428, and died in 1479. Given that these are evidently intended as portraits, the altarpiece must have been ordered before the death of Antheunis Seghers in 1475, which means that its production may logically be linked with the expansion of the chapel's apse in 1473- 74 though we lack details of Jacob de Ceuninc and Clara van Hulsen in those years.

_Thirteen_1474_79.jpg)

The left panel of the diptych represents the Betrothal of Saint Catherine of Alexandria.

Sir John and Lady Donne are shown wearing Yorkish collars of gilt roses and suns from which hangs the Lion of March pendant of King Edward IV. The altarpiece may have been commissioned when Sir John was in Bruges in 1468 for the marriage of Margaret of York, Edward's sister, to Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, or possibly on a later trip to nearby Ghent.

The reverses of the shutters depict Saint Christopher and Saint Anthony Abbot painted in tones of grey to resemble stone statues.

_ca_1475.jpg)

_ca_1475.jpg)

_ca_1475.jpg)

_ca_1475_Two.jpg)

_ca_1475_Three.jpg)

_ca_1475.jpg)

Here too, the donor kneels on the far left behind a low wall. The stereo metric planning and consistency with which Memling sets down his architectural features is characteristic. As in the Prado triptych, he locates the Nativity and the Adoration of the Magi in the same building, but this time at a totally different angle and in another room, as if he had used a model that he could simply change around. In both paintings, the Child is born in the back room of the stable, with the ox and the ass. The stable of the Magi scene is shown from the rear in the left wing of the Floreins triptych. Every element tallies: the pilasters, the corbels, the beams, the little transverse roof and the hole in the thatching. The perspective of the left wing has two vanishing points with a viewpoint shifted to the right. That of the central panel is frontal, with a viewpoint moved slightly to the left, as is the case in the Columba altarpiece. Despite this, Memling placed the Virgin in the middle, directly in front of a column.

His architectural interest is also apparent from the right wing. This Presentation in the Temple is set in the southern part of the crossing of the former Cathedral of Saint Donatian. The line-of-sight is directed towards the portal of the north transept, with the beginning of the ambulatory on the right. Bruges' Romanesque principal church would indeed have been an ideal choice for the part of the biblical Temple. Like the Prado triptych, the Adoration of the Magi is constructed symmetrically in the older Cologne style with the Virgin at its centre. Scholars rightly emphasized the heightened humanism of this scene, and its greater intimacy with the viewer in comparison to the Prado altarpiece. This Joseph is an affected witness to the Nativity, while the formal, prayerful pose of the Madrid Virgin and angels has given way to a joyful, hand-spreading gesture, expressive of surprise and wonder. The Christ Child in the Adoration of the Magi roguishly seeks eye contact with the viewer. One end of the eldest king's cloak is painted over the frame.

The triptych is authenticated, dated and identified by an original inscription, on the original frame, and thus forms a key element (more so even than the St John altarpiece) in the reconstruction of Memling's oeuvre, and knowledge of his name and signature. The patron is Jan Floreins, also known as Van der Rijst, a member of the monastic community of Bruges' Saint John's Hospital. He is dressed in a black habit, and kneels behind a low wall of the ramshackle stable in Bethlehem reading a book, most likely the passage dealing with the Wise Men from the East in Saint Matthew's Gospel. The figure 36 (his age) is carved into the stone alongside his head. A youth in worldly costume stands behind him.

Jan Floreins belonged to the de Silly family, who were known as the lords of Rijst thanks to an alliance with the Brabant Van der Rijst family. He was born in 1443, and joined the religious community of Saint John's Hospital in 1472, before becoming master in 1488. He apparently held that position until 1497, and probably died in 1504 or 1505. His initials and the arms of his family appear on the frame of the reverse of the wings. The presence of the youth behind Jan Floreins has not yet been explained.

The myth of the sick Memling who portrayed himself wearing a patient's bonnet and peering through the window on the right of the central panel arose during the eighteenth century. The prophetess Anna who looks at the viewer in the right wing seems to be intended as a portrait. The boy on the far right of the central panel, next to the Moorish king, who looks directly at us, and who can have no iconographical function in that position, also appears to be a portrait.

The Three Kings were invoked, amongst other things, against falling sickness and death without benefit of the last sacraments. They were also the protectors of pilgrims. Their portrayal was thus a natural theme for a hospital. St Veronica too was the protectress of those who died suddenly. The destination of the altarpiece is unknown, but Jan Floreins is likely to have installed it on a side altar of the hospital chapel. The detailed inscription with the donor's name is, after all, intended to be read by everyone.

_1479.jpg)

The myth of the sick Memling who portrayed himself wearing a patient's bonnet and peering through the window on the right of the central panel arose during the eighteenth century.

As in the Saint John altarpiece, the name of the artist and the date are included in an inscription in classical Roman capitals on the original frame. Memling used this classical typography - no different from that of Bellini or Mantegna - in several of his works. It is a very early, if not the earliest, example of humanist script in the Low Countries.

_1479.jpg)

The figure of Saint John on the reverse of the left wing was held around that period to be a self-portrait of the artist, because Jacob van Oost the Elder made an engraving of it, which he identified in that way.

The figure of Saint John on the reverse of the left wing was held around that period to be a self-portrait of the artist, because Jacob van Oost the Elder made an engraving of it, which he identified in that way.

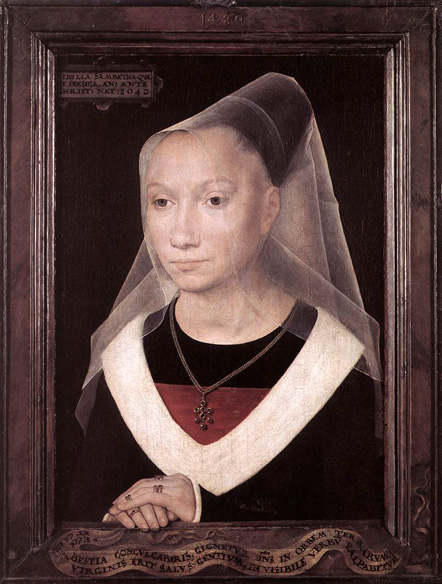

An earlier example of this type of portrait, with the same background, frame and date is the Portrait of Gilles Joye, dating from 1472. The Portrait of Jacob Obrecht also has this type of marbling on its frame. The portrait is somewhat disfigured by a painted metal cartouche top left and a banderole with an inscription on the frame at the bottom, which identify the woman as the Sibyl of Persia (SIBYLLA SAMBETHA QUAE / EST PERSICA). Judging from the style, these were added in the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century. The fingertips painted over the frame are original. This trompe-l'oeil technique is an example of a process frequently applied by Memling with the aim of breaking through into the real space beyond the picture plane. The painted strip on which the sitter's hands rest is not a window-sill, but is seemingly intended as a continuation of the frame.

The sitter of this celebrated portrait was identified in the 19th century as Maria, the second daughter of Willem and Barbara Moreel. However, later this identification was not generally accepted. The painting is also known as the Sibyl of Sambetha on account of an inscription on the scroll.

The painting was destined for the altar of the Tanners' guild in the most easterly chapel of Our Lady's Church in Bruges. It was donated by Pieter Bultinc, 'tanner and merchant', and his wife Katelyne van Ryebeke, as recorded on the old frame, which survived until the end of the eighteenth century.

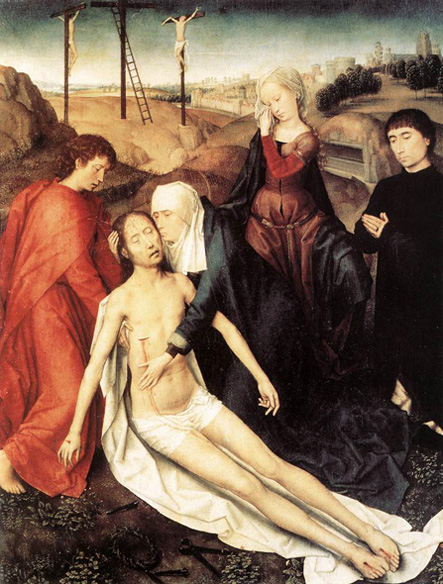

The principal scene is a Lamentation on Golgotha beneath a glowering evening sky. The left wing represents the donor with his patron saint, while the right wing features Saint Barbara, the hospital saint par excellence.

The composition is a development on an idea of Rogier van der Weyden, who was the first to reduce the Lamentation to its three principal protagonists (apart from Christ) in a number of smaller compositions. The body with its stiff, open arms and closed legs, knelt over by the praying Virgin, first appears in another work by the same master, namely the Lamentation in The Hague (Mauritshuis). The scene as a whole is portrayed in deep and somber tones. The predominance of purple - including the marbling of the frame - means that the altarpiece is literally enveloped in the color of the Passion.

Two versions of this Lamentation are known: the central panel of the Kaufmann triptych in Rotterdam and the Rome Lamentation, both of which were probably painted at an earlier date. The former in particular may be seen as the immediate compositional predecessor of the Reins triptych.

Doubts as to the authorship of the work were expressed from an early stage, probably because the figures of Saint John and Mary Magdalene did not meet the idealized Memling image that had been formed by the nineteenth century, and because of the lack of an inscription with the artist's signature. Despite these doubts, this little triptych is a masterpiece, executed with the utmost delicacy.

The central panel was partially copied (landscape, Christ and St John) in the Santa Barbara Lamentation by a follower of Memling from the late fifteenth century.

_1480.jpg)

_1480.jpg)

_1480_Two.jpg)

_1480.jpg)

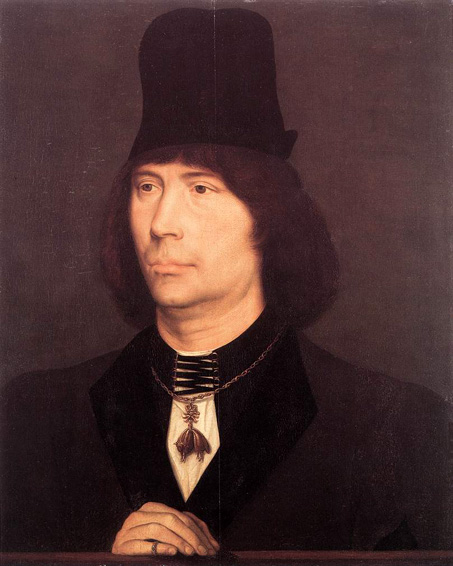

When closed, this diptych would have displayed the coat-of-arms that is still to be found on the reverse. The man probably belonged to the Lespinette family (Franche-Comte). Since its auction (as a work by Antonello da Messina) in 1894, the painting has been accepted as a Memling. It is generally compared with his portraits from the 1480s, and shows a particular similarity in its modeling to the Bruges Portrait of a young woman of 1480.

It is understandable that some people should have been inclined to attribute this admirable portrait to Antonello, such is its precision and assurance of drawing and modeling of the face; but in the features, which are as though engraved, and the pointed steeple visible in the background, give a Flemish character of this picture.

When closed, this diptych would have displayed the coat-of-arms that is still to be found on the reverse. The man probably belonged to the Lespinette family (Franche-Comte). Since its auction (as a work by Antonello da Messina) in 1894, the painting has been accepted as a Memling. It is generally compared with his portraits from the 1480s, and shows a particular similarity in its modeling to the Bruges Portrait of a young woman of 1480.

It is understandable that some people should have been inclined to attribute this admirable portrait to Antonello, such is its precision and assurance of drawing and modeling of the face; but in the features, which are as though engraved, and the pointed steeple visible in the background, give a Flemish character of this picture.

Originally purchased as an Antonello da Messina, the painting has been definitively ascribed to Memling since 1896.

The doubt that is sometimes expressed as to Memling's own execution of this painting is entirely unwarranted. It is true that the dotted contours of the oval trees in the left background are inserted rather mechanically, and the perspective of the round column bases is rather forced, but none of this is sufficient reason to attribute such a refined and daintily executed painting to the workshop.

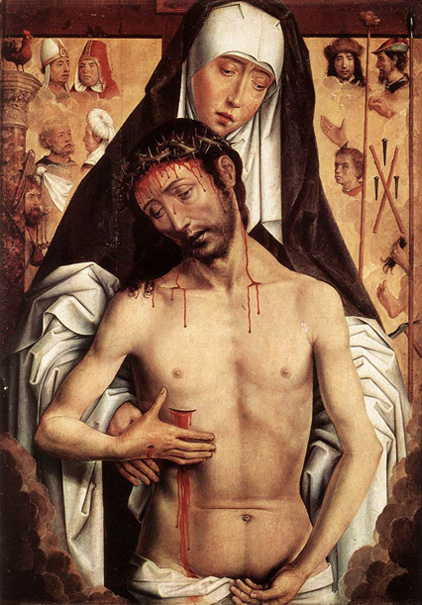

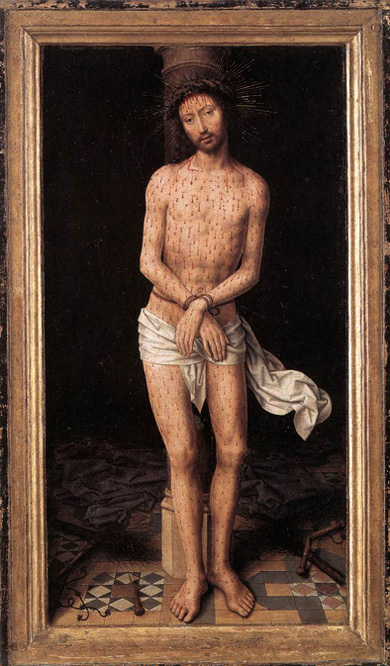

It was not until the Genoa panel came to attention at the 1947 exhibition in Florence that it was accepted by most art-historians as a Memling of high quality. The work does, indeed, exhibit the highly polished finish, anatomical definition and soft lighting of Memling's portraits. Christ wears a dark, purple-brown robe, and turns sorrowfully towards his mother, in the original right wing, to show his wounds. The droplets of blood, mixed with sweat, are rendered in a highly refined, transparent manner. Similar portrayals, albeit more frontal, are to be found in the circle of Dieric Bouts, especially in the work of Albert Bouts, where the type probably first arose. Memling's version is one of the most 'human' interpretations, because it presents Christ not as a terrible emblem of the Passion (with the king's cloak or cane from immediately after the Flagellation and the Crowning with Thorns), but as a sorrowful man who still bears the marks of his torture.

This is one of the variants in the series of Virgins accompanied by one or more angels that proved to be such a successful part of Memling's oeuvre. The Child's pose is the typological match of the Virgin Enthroned in Berlin, with both examples deriving from a prototype of Rogier van der Weyden. The angels hold musical instruments - a partially hidden lute on the left, and a fiddle on the right. Their albs and wings are painted in refined hues, in Memling's characteristic fashion: the angel on the left in white with grey wings, and the one on the right with a delicate lilac sheen and light purple wings, blending into yellow around the edges. The Virgin sits in a small, enclosed garden, as in the Munich diptych, before a hedge of white and red roses, with a white lily in their midst. The Marian symbolism of this is clear, as is the fact that the spot is sealed off from the remainder of the landscape by a reinforced wall to the rear. Mary is allegorically represented as a fortress.

The little work must have been executed in the 1480s, given its stylistic similarities with the Diptych of Jean du Cellier.

The work was not reported until 1937 and the original date 1481 on the frame has been overlooked until now. It is painted in trompe-l'oeil gilded numbers. The date 1480 on the Portrait of a Young Woman (Memlingmuseum, Bruges) and that on the Reins triptych are executed in precisely the same way.

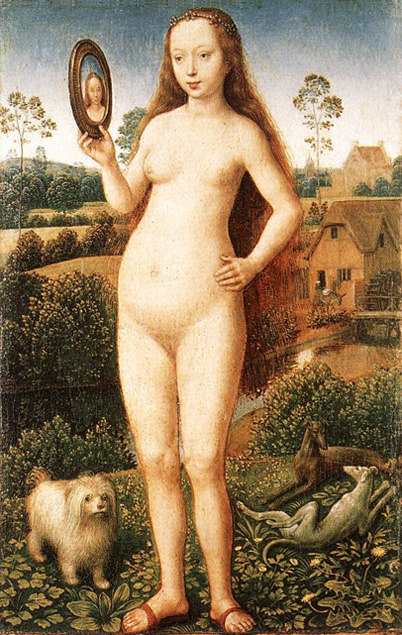

Memling constructed a narrative space in this work which is exemplary for northern European painting. On the back wall of the bathroom a window is open, revealing a roof terrace: "And it came to pass in an eveningtide, that David arose from off his bed, and walked upon the roof of the king's house: and from the roof he saw a woman washing herself; and the woman was very beautiful to look upon. " This is the description of events in the Second Book of Samuel (chapter 11), prior to the king committing adultery and murder. Below the palace is a portal leading into a church on which a wall relief can be seen depicting the death of Bathsheba's husband, the Hittite Uriah, whom David sent to certain death in battle. Beside the portal projects an apse on whose wall can be seen painted sculptures of Moses and Abraham as representatives of law.

The painting is divided into a dominant scene in the foreground and a secondary scene, subordinate to this, in the background. This background narrative is of the traditional pattern that of painted church sculpture. Memling was not so much concerned with the biblical story - which may have served as justification of a nude figure - as with the translation of a biblical motif into a domestic setting in 15yh-century Flanders. Moreover, the upper left-hand corner has been added at a later date, probably in the 17th century. The original corner piece, now in the Chicago Art Institute, shows David giving a messenger a ring for Bathsheba.

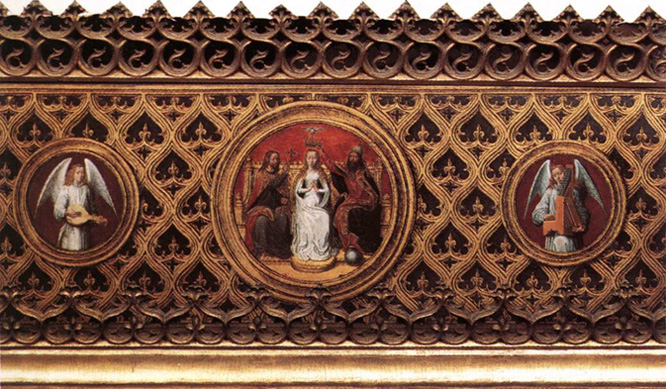

For the first time the painting includes the Italianate motif of putti stretching festoons across the scene at the top. Similar figures appear on a couple of other occasions in Memling, including the Resurrection triptych (Paris, Musee du Louvre) and the Virgin Enthroned in Florence.

_ca_1483.jpg)

_ca_1483.jpg)

_ca_1483.jpg)

On the reverse the gold chalice with a serpent can be seen. It refers to the legend of Saint John the Evangelist.

The left wing of the diptych representing Saint John the Evangelist is in the Alte Pinakothek, Munich.

_ca_1483.jpg)

The inner side of the panel represents Saint Veronica.

The Groeninge Museum has an important Memling, the Moreel triptych, painted in 1484 for the prominent Bruges family Moreel. It was designed for an altar in Saint James' Church dedicated to Saints Maurus and Giles. The ethereal, paradisiacal space that encompasses the three panels, in which slim, well-proportioned figures - motionless and expressionless - participate in a sort of communal salvation, is characteristic of Memling's idealizing mode of expression. It is also one of the first occasions on which a complete family is portrayed and thus marks the birth of the group portrait. The central panel depicts Saints Christopher, Maurus and Giles. The donors and their children are shown kneeling in the wings, in a landscape that extends from the central panel. The man is protected by Saint William of Maleval, the woman by Saint Barbara. The couple is Willem Moreel (who died in 1501), a prominent Bruges politician, and his wife Barbara van Vlaenderberch, or van Hertsvelde (died 1499). Willem Moreel, lord of Oostcleyhem, was burgomaster in 1478 and 1483, bailiff in 1488 and municipal treasurer in 1489. He was also active for a time in the grocers' guild and as a banker for the Banco di Roma. The couple was granted permission in 1484 to set up an altar dedicated to Saint Maurus and Saint Giles at Saint James' Church, and to prepare their tomb nearby. The donors' resemblance to authenticated portraits of the same couple in Brussels, and the fact that the painting is dated 1484 and clearly portrays Saint Giles with a monk identifiable as Saint Maurus, a follower of Saint Benedict, demonstrates beyond doubt that this was once the Moreel family altarpiece in Saint James' Church, and that it was specifically produced for this purpose. The couple had five sons and thirteen daughters.

The reverse side of the wings shows Saint John the Baptist (left wing) and Saint George (Right Wing).

The triptych is shown in its original frame.

_1484.jpg)

_1484.jpg)

Saint Maurus and Saint Giles were probably selected on the basis of the surnames Moreel and Hertsvelde. `Maurus' and `Moreel' share the same etymology (`Maurus' = `Moor' - the Moreel coat-of arms includes Moors' heads) and the hind (`hert') of Saint Giles can be linked to the name of Hertsvelde. The same saints appear in an illuminated Book of Hours that belonged to the couple. The forenames and surnames of the donors are thus represented by the linkage of the patron saints in the wings with the saints depicted alongside them in the central panel.

Saint Christopher was invoked against sudden death. It was believed that whoever looked upon him would not die that same day without benefit of the last sacraments. This might be one reason for his highly unusual selection as the principal figure of a major altarpiece. Saint Christopher's head might have been inspired by that of Longinus in the right wing of the Master of Flémalle's Passion altarpiece, which was to be found in Saint James' Church at that time. A spring rises from the rocks on the far right, next to Saint Giles. This symbolizes the proclamation of the Good News to refresh the faithful, and is thus a direct allusion to the presence of the Christ Child.

_1484.jpg)

_1484.jpg)

The accurate rendering of the numerous players may create the impression that the painter wanted to present an ensemble of contemporary musical instruments. In fact, however, the composition reveals an arrangement of strict symmetry, partly suggested by the hierarchical order of angels and the related symbolism of instruments, although the classification is not as clear as in the works of Giotto or Geertgen. In the central panel depicting Christ, six singing angels represent music of the highest order. On each side of Him (on the right of the first panel, and on the left of the second), in a mirror arrangement, are two wind instruments: one trumpet on each side and a zink and busine, representing the order of "trumpeting" herald angels. Moving further away from the centre, on the left we see stringed instruments: a lute, a tromba marina and a psaltery, while on the right the mellower, quieter instruments, a portative organ, a harp and a fiddle. The psaltery, for example, was used exclusively to accompany psalms and beseeching prayers.

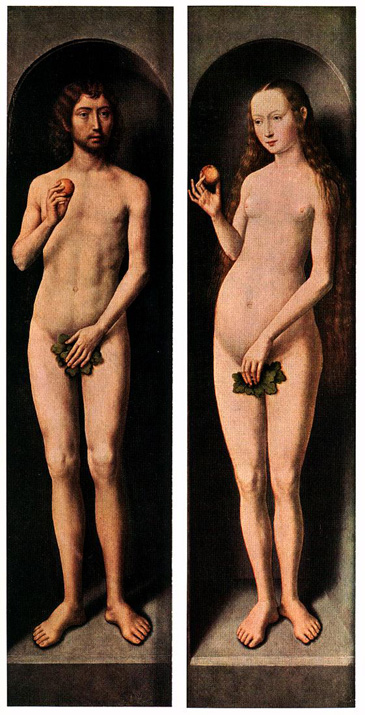

_1480_s.jpg)

_ca_1485.jpg)

The purely erotic character of the nude is indeed exceptional for its time. This is the only example in which the female genitals are shown uncovered. This woman, with a diadem in her long hair, who looks in the mirror and unashamedly shows off her nakedness but for the sandals on her feet, simultaneously represents Vanity and Lust. She is the antithesis of the virgin in the little painting in the Musée Jacquemart-André. To her left there is a griffon, a breed of dog that is customarily included in paintings whose subject is marriage or physical love. The significance of the amorous greyhounds on the right is also clear. The watermill, which constantly alludes in Memling to the Incarnation and which is once again placed prominently in the landscape, might be intended here as a contrast with the sinful ways of the flesh portrayed in the foreground. The woman's genitals in the Vanity scene correspond with the toad - the demonic creature to be seen over the genitals of Death. It is not possible to determine from any physical clues whether this panel was originally located to the left or right of the central panel.

In terms of composition (poses and the positioning of the banderoles) the layout presented here - with Death and Hell to the left and right respectively - would appear most satisfactory. The glowing reflection of the flames on the bodies in the jaws of hell recalls the Gdansk Last Judgment.

_ca_1485.jpg)

Although the image might appear familiar, this representation is rare, if not unique. Christ is, indeed, depicted as a kind of Ecce Homo, but he is shown at the point before he is dressed in the imitation king's cloak, the cane is placed in his chained hands and he is exposed to the mockery of the mob. He is shown naked apart from a loin-cloth, after the Flagellation but nevertheless with the Crown of Thorns on his head. He is thus presented in a kind of compassionate conflation of the Flagellation and Ecce Homo themes: a Man of Sorrows with the arma Christi portrayed shortly before the Crucifixion. The slight asymmetry of the column, which stands a little to the left of center, and of Christ's feet, which are located somewhat to the right of the centre line, creates a visual balance between the figure and the architecture on a floor pattern that is nonetheless perfectly symmetrical. Memling applied a similar procedure on several occasions.

The painting was not discovered until late (exhibition Bruges 1958). It is an autonomous devotional work which has survived all but intact in its original frame. Its attribution to Memling cannot be doubted. The slim, elongated figure is comparable stylistically with later works such as the Stuttgart Bathsheba, the Basle St Jerome and the Greverade triptych. The somewhat rigid modeling and the simplified, direct brushwork also point in that direction

This fairly large panel is not very well known, and is sometimes treated with a degree of caution. Nevertheless, it is a fine example in every respect of Memling's vision and technique. Monumentally conceived, yet executed with an undramatically fresh and guileless realism, this Saint Jerome is one of the most elegant large figures in the artist's oeuvre. The spatial character of the slim, half-naked saint is comparable with the Stuttgart Bathsheba. The extremely free under drawing, the elongated body shapes and a physiognomy that seems to prefigure that of Van Cleve or Massys suggest that both paintings were executed fairly late, although additional evidence would be required for more precise dating. A characteristic Memling trait is the way the emblematic attributes such as the crucifix, the lion and the cardinal's clothes are included in a natural manner. Taken together, it is like a moment from a story, despite the fact that the depicted elements refer to different periods of the saint's life. Furthermore, the crucifix consists of a genuine flesh-and-blood little body, put to death in miniature, with no attempt on the artist's part to portray it as a vision.

We do not know whether the panel was autonomous, or whether it had wings or a companion piece. The small fragment depicting Saint Jerome and the Lion might have formed part of the left wing (private collection).

The odd way the image is cropped to the left and right is not the result of its having been narrowed at some stage, but is in fact deliberate. The angled position of the arch might indicate that this was once a left wing. The panel has been cut off at the top and bottom. Considering the size of the figure and the wooded landscape, it could be a side panel for the Saint Jerome in Basle.

In providing a glimpse of landscape in the right-hand corner, Memling obeys a convention which was common in early Renaissance portraiture and which would remain popular even into the 16th-century. In keeping our view into the outdoors narrow, he neither distracts our attention from the sitter nor influences the mood of the scene.

The panel is the left wing of a triptych. We have to assume that the young man is worshipping a holy figure, probably a Virgin and Child, located in the middle of the loggia. In view of his position on the left, there must have been a young woman in the right wing of what will have been a folding devotional triptych with matching panels of the classic type.

The reverse of the portrait is an exquisite still-life. A small Italian maiolica vase stands on an Oriental carpet in a niche. It holds a bouquet of lilies, irises and columbines, symbolizing Mary's virginity, her suffering and Christ's birth and death. The vase also bears Christ's monogram. This flower piece not only argues in favor of a central panel depicting a Virgin and Child, it must also be viewed as a kind of emblem of the donor's personal Christian vocation.

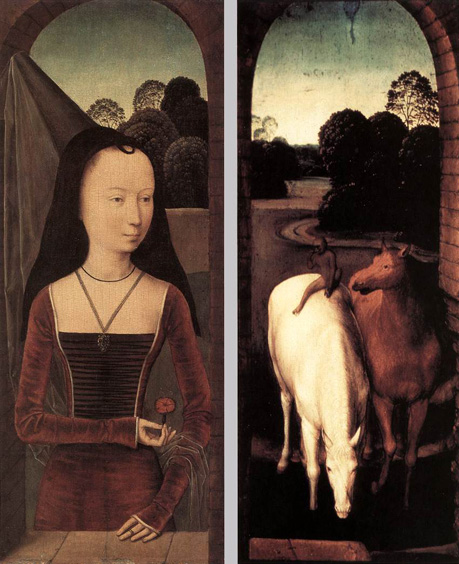

The vanishing point for the perspective construction of both paintings is located on the line separating them. That means, taking account of Memling's consistent logic in this respect, that they cannot have been intended as the wings of a triptych, but were conceived as continuous scenes, separated only by their frames. We can no longer determine whether the diptych was fixed or folding. The panels are very thin, which might indicate that they had a painted rear which was subsequently sawn off. The woman holds a carnation in her hand, which is a long-established symbol of marriage. The white horse, on which a grinning monkey sits, bends down to drink, while the brown horse turns its head towards the woman. The horse, which is often used in both art and literature as a symbol of love, appears here in a double role. The white one with the monkey - the symbol par excellence of sinfulness, lust and selfishness - is the bad lover who is concerned only with self-gratification (slaking its thirst), while the brown horse gazes faithfully and unselfishly at its mistress.

The physiognomy of the woman corresponds with Memling's anonymous female type, which is to be found in both saints and angels. This fact alone indicates the purely emblematic character of the representation. What is more, if this figure had had a male portrait as a companion piece it could not have appeared in a left wing. The young woman is dressed in the manner of the Burgundian Court in the 1470s with a high hennin or `steeple' headdress and long train, which might place the allegory even more clearly in the realm of chivalry and courtly love.

In the Virgin of the left wing, the features of the Virgin in van der Weyden's Columba Altarpiece can be seen, with her slightly tilted head and soft facial features almost frozen in gentle humility. In Memling's picture the Virgin and Child seem more animated, their gestures more natural. Christ, depicted in a pose similar to the same figure in van der Weyden's work, reaches eagerly for the apple held by his mother. This gesture expresses the acceptance of his later Passion, which was necessary to redeem humanity from original sin (symbolized by the apple).

This panel shows Memling's mastery of a rich vocabulary of allusions in the Flemish tradition of a van Eyck. As in the Arnolfini Marriage, a convex mirror hangs on the wall behind the Virgin and captures the entire scene. We can see the nobleman at prayer and the Virgin at his side. His holy vision has become a reality through the painter's art, which, in a metaphorical sense, is a witness to the event. The form of the diptych separates the levels of meaning: the sacred images of the Virgin and Child are on one side and a secular portrait of the donor on the other. However, these levels of meaning are embedded in a unified and domestic space which envelops both panels - a real room in the house of a prosperous nobleman. The divine sphere has been shown to enter the sphere of this Bruges nobleman's everyday world.

The original frame states the name and age of the donor, together with the date. He is Maarten van Nieuwenhove, portrayed in 1487 when he was 23. He was born on 11 November 1463 to a prominent Bruges family, several members of which held important civic posts (burgomaster, councilor, municipal treasurer) or worked for Maximilian of Austria. Links with the latter were to cost Maarten's brother Jan his head in 1488. Maarten was a councilor in 1492 and 1494, captain of the civic guard in 1495 and 1498 and burgomaster in 1497. He died on 16 August 1500, as recorded by his tombstone in the family chapel in the Church of Our Lady. He was evidently still unmarried at the time the painting was commissioned. His future bride, Margareta Haultain, was to outlive him by twenty years. His coat-of-arms and motto IL YA CAVSE are incorporated in the stained-glass window behind the Virgin. The window also features four medallions containing a vivid emblem that illustrates his family name: a hand sowing seeds over a garden of flowers (Nieuwenhove = new garden). Maarten's patron saint, Saint Martin, is represented behind him, again in the form of a stained-glass window. The medallions showing Saint George and Saint Christopher to the Virgin's right might be personally chosen protectors. The view through the window to the rear of the portrait appears to show the Minnewater Bridge in Bruges.