1400 - 1464

Rogier van der Weyden, also known as Rogier de le Pasture is, with Jan van Eyck, considered one of the greatest exponents of the school of Early Netherlandish painting.

Rogier van der Weyden was born in Tournai as 'Rogier de le Pasture' (Roger of the Pasture) in 1399 or 1400. His parents were Henri de le Pasture and Agnes de Watrelos. The family had settled before in the city of Tournai where Rogiers father worked as a 'maitre-coutelier' (knife manufacturer). In 1426 Rogier married to Elisabeth, the daughter of the Brussels shoemaker Jan Goffaert and his wife Cathelyne van Stockem. Rogier and Elisabeth had four children: Cornelius who became a carthusian monk was born in 1427, a daughter Margaretha in 1432. Before 21 October 1435 the family settled in Brussels where the two younger children were born: Pieter in 1437 and Jan the next year. From the second of March 1436 onwards held the title of 'painter to the town of Brussels' (stadsschilder) a very prestigious post because Brussels was at that time the most important residence of the splendid court of the Dukes of Burgundy. It was at the occasion of his move to the Dutch-speaking town of Brussels that Rogier began using the Dutch version of his name: 'Rogier van der Weyden'.

Less is certain about Rogier's training as a painter. The archival sources from Tournai (completely destroyed during World War II, but luckily partly transcribed in the 19th and early 20th century) are somewhat confusing and have led to different interpretations by scholars. From a document it is known that the City Council of Tournai offered wine in honor of a certain 'Maistre Rogier de le Pasture' on March the 17th 1427. However, on the 5th of March of the following year the records of the painters' guild show a certain 'Rogelet de le Pasture' entered the workshop of Robert Campin together with Jacques Daret. Only five years later, on the first of August 1432, Rogier de le Pasture obtains the title of 'Master' (Maistre) as a painter. Many have doubted whether Campin's apprentice 'Rogelet' was the same as the master 'Rogier' that was offered the wine back in 1426. The fact that in 1426-1427 Rogier was a married man in his late twenties, and well over the normal age of apprenticeship has been used as an argument to consider 'Rogelet' as a younger painter with the same name. In the 1420's however the city of Tournai was in crisis and as a result the guilds were not functioning normally. The late apprenticeship of Rogier/Rogelet may have been a legal formality. Also Jacques Daret was then in his twenties and had been living and working in Campin's household for at least a decade. It is also possible that Rogier obtained an academic title (Master) before he became a painter and that he was awarded the wine of honor on the occasion of his graduation. The sophisticated and 'learned' iconographical and compositional qualities of the paintings attributed to him are sometimes used as an argument in favor of this supposition. The social and intellectual status of Rogier in his later life surpassed largely that of a mere craftsman at that time. In general the close stylistic link between the documented works of Jacques Daret, and the paintings attributed to Robert Campin and Rogier van der Weyden is considered as the main argument to consider Rogier van der Weyden as a pupil of Robert Campin.

After he settled in Brussels Rogier began a prosperous career that would make him the most famous painter in Europe at the time he died in 1464. Different properties and investments are documented and witness his material prosperity. The portraits he painted of the Burgundian Dukes, their relatives and courtiers, point to his good relations with the richest and most powerful sovereigns in Europe.

The Miraflores Altarpiece was probably commissioned by King Juan II of Castile, since Juan II donated it to the Monastery of Miraflores in 1445. In the holy year 1450 Rogier quite possibly made a pilgrimage to Rome which brought him in contact with Italian artists and patrons. The Este and Medici family commissioned paintings from him. The Duchess of Milan, Bianca Maria Visconti, sent her court painter Zanetto Bugatto to Brussels to become an apprentice in Rogier's workshop. Rogier's international reputation had increased progressively. In the 1450's and 1460's scholars like Cusanus, Filarete and Facius referred to him in superlatives: 'the greatest', 'the most noble' of painters.

Not a single work that can be attributed with certainty (on the basis of documentary evidence) to Rogier van der Weyden survives. Rogier's most famous paintings were the four vast panels with the 'Justice of Trajan' and the 'Justice of Herkenbald', painted for the 'Gulden Camere' (Golden Chamber) of the Brussels Town Hall. The first and third panels were signed, and the first dated 1439. All four were finished before 1450. They were destroyed in the French bombardment of Brussels in 1695, but are known from many old descriptions, from a free partial copy in tapestry (Bern, Historisches Museum) and from other free and partial copies in drawing and painting. The paintings probably measured ca. 4,5 m. each, which was an enormous scale for a painting on panel at that time. They served as 'examples of justice' for the aldermen of the city who had to speak justice in this room. According to the praising descriptions (by Albrecht Durer, Calvete de Estrella and Isaac Bullart) the paintings had a strong emotional impact on the beholder. As can be seen in still extant paintings attributable to him, Rogier van der Weyden was a master in the depiction of emotions and grief.

This aspect of his style is also apparent in the Deposition (Madrid, Museo del Prado) that has been attributed to Rogier since the 16th century. It was probably commissioned by the 'Saint Georges Guild of the crossbowmen' for the church of 'Onze-Lieve-Vrouw van Ginderbuiten' in Leuven. Although the pedigree of this work is known it cannot be related to Rogier on a documentary basis with certainty. Some authors like Max J. Friedlander or more recently Felix Thurlemann consider it as a work of Robert Campin on the basis of stylistic comparison.

His vigorous, subtle, expressive painting and popular religious conceptions had considerable influence on European painting, not only in France and Germany but also in Italy and in Spain. Hans Memling was his greatest follower, although it is not proven that he was a direct pupil of Rogier. Van der Weyden had also great influence on the German painter and engraver Martin Schongauer whose prints were distributed all over Europe since the last decades of the 15th century. Indirectly Schongauer's prints helped to disseminate Van der Weyden's style.

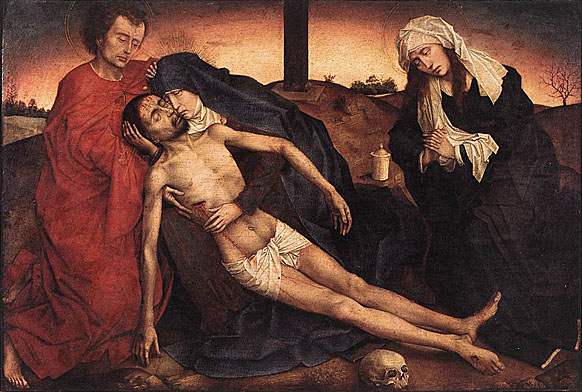

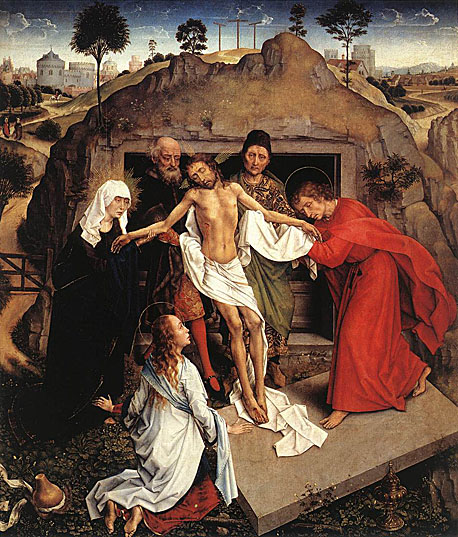

The earliest painting that can be ascribed to Rogier van der Weyden with any certainty is also the artist's greatest and most influential extant work: the great Deposition. It was an altarpiece, intended for the chapel of the Confraternity of the Archers of Leuven, who commissioned it.

The Deposition was an altarpiece, intended for the Chapel of the Confraternity of the Archers of Leuven, who commissioned it. (The two small crossbows in the lower spandrels of the tracery in the picture refer to the Confraternity.) Mary of Hungary (1505-1558), Regent of the Netherlands, acquired the painting from the Archers of Leuven before 1548. Later it came into the possession of her nephew King Philip II of Spain (1527-1598; king from 1556), who finally placed it in the monastery fortress of the Escorial he had founded near Madrid. At that time the Deposition formed the centre of a triptych, but there is no indication that the side wings were originally part of the work, it is more likely that the Deposition was originally a single panel.

At about 2.2 meters high and 2.6 meters wide, the painting is very large by the usual standards of Early Netherlands' pictures; in terms of concept it is truly monumental. Ten figures in all cover the painted surface almost entirely, with their heads close to the upper edge of the panel. The body of Jesus has already been removed from the Cross, and is received by two elderly men, the bearded Joseph of Arimathaea and Nicodemus. Surrounded by Jesus' mourning friends they are holding His dead body for a moment before setting it down. Mary is sinking to the ground in a faint beside her son, and is supported by John, the favorite disciple of Jesus, and by one of the holy women. On the extreme right, the despairing Mary Magdalene seems on the brink of collapse.

The scene shown would have lasted for only a moment, but there is nothing momentary about its depiction, which is quite detached from the historical event. Rogier achieves this effect principally by placing the group in a painted niche like an altar shrine; the hill of Golgotha, the Place of Skulls where the Cross stood, is suggested only by skulls and arm bones on the narrow strip of stone floor. A connection is thus established with those gilded shrines holding painted statues that were a particularly costly and lavish form of retable. However, Rogier was not imitating a carved altar. He shows "live" figures rather than statues, and the life-like effect is emphasized by their appearance, almost life-size, in the place where mere wooden statues would be expected in an altar. Using such methods, Rogier gives them the three-dimensionality of statues but the look of a painting, which is much more life-like than sculpture.

However, such considerations would have played only a minor part in Rogier's decision to set the scene in the painted altar niche. His primary concern was to emphasize the forcefulness of the depiction. Rogier even departs deliberately from what can be rationally imagined, and so breaks with the manner of realistic spatial depiction that had only recently been achieved in painting. The niche he paints is deep enough at the bottom of the picture to accommodate several figures, the upright of the Cross, and the ladder leaning against it; but in some areas at the top it seems to come close to the surface of the picture - the helper on the ladder is pressed tightly into the shallow upper space of the shrine, while the head of the bearded Joseph of Arimathaea just below seems to protrude from the picture. All the figures are brought forward by the golden back wall so that the space surrounds them closely: convincing as their actions may look individually, there would never really have been room for them all. The result is a sense of timelessness and an almost oppressive intensity.

The painted niche offered Rogier another advantage: he could retain the gold background usual in medieval painting without offending against the demands of naturalistic depiction. The background of the painting is, in fact, a real gilded surface and also a pictorial representation of one - the back of the shrine.

Rogier relates the figures to each other in a masterly composition, yet he emphasizes a number of different accents. The limp body of Christ is at the centre, and appears to be held quite naturally by the two men so that it is almost facing the observer, with hardly anything else encroaching on it. This is the part of the picture intended to inspire the greatest reverence, referring to the sacrament in which, in the Catholic faith, the host and the wine become the body and blood of Christ. During divine service the bread and wine would have stood on the altar below this picture, and when the priest raised the host above his head during the ceremony, the congregation would have seen him doing so directly in front of the painted body of Christ.

The almost radiant body is immaculate and beautiful, not disfigured by the marks of scourging, and its delicate but almost swelling form has a distinctly sensuous softness. Only the marks of the five wounds are ugly gashes running with blood. However, the long trickle from the wound in Christ's side passes over the body like a delicate line that traces the curve of the stomach.

The other main character in the picture is Mary. The Mother of God, sinking to the ground as if dead, forms a parallel to Christ, allowing the artist to create a link between the two main groups in a bold effect of composition, since they are moving in different directions: Christ is being carried away to the right, while Mary is falling to the left. At the same time, the correspondence between the figures illustrates an important theological idea of the time Mary's own compassionate suffering and her part in Christ's act of redemption. On the right of the picture not directly involved in the action, stands Mary Magdalene. Her magnificent, worldly garments, with the low-necked dress showing her full, sensuous breasts, indicate that she is the "great sinner" who has abandoned her depraved way of life and turned to Christ in repentance. In terms of composition, the Magdalene's figure closes off the picture on the right like a large bracket, matching the similarly bowed figure of John on the left. The curve of Mary Magdalene's cloak, sweeping forward into the picture, is echoed by the hem of the brocade robe worn by Nicodemus, and is continued in the left half of the picture by the folds in the Virgin Mary's blue dress. Such overlapping forms and lines determine the structure of the whole picture: the curve of Christ's body is continued in the Magdalene's left arm, and is crossed by the diagonal running in the opposite direction from the eyes of Nicodemus, through the hands of Christ and Mary, to the eye sockets of the skull. Christ's left arm too echoes the movements that seem to curve and turn on each other at the centre of the picture.

The Deposition is among the outstanding masterpieces of Netherlands' art, and one of the mainstays of Rogier's fame. As the work of a painter aged 35 to 40, it can hardly be described as a youthful production, yet only with this painting can we begin to see Rogier more clearly as an artistic personality. Most important of all, the picture shows unmistakable similarities with some of the major works of the Master of Flemalle.

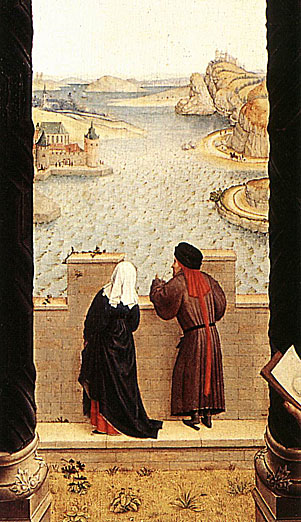

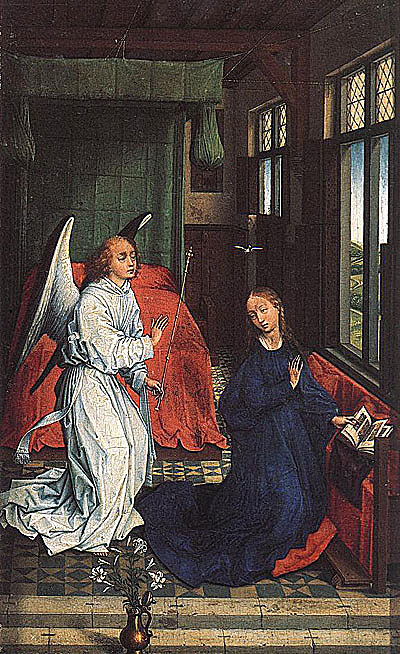

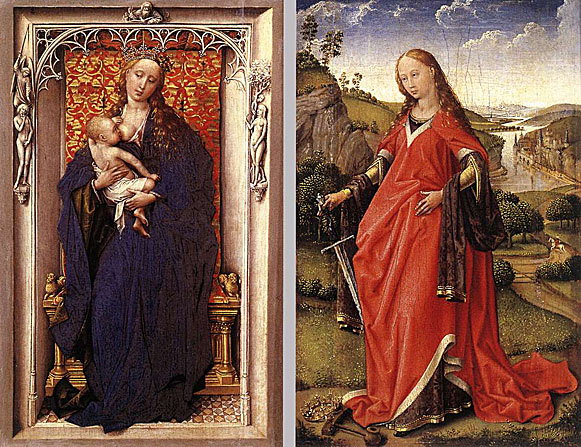

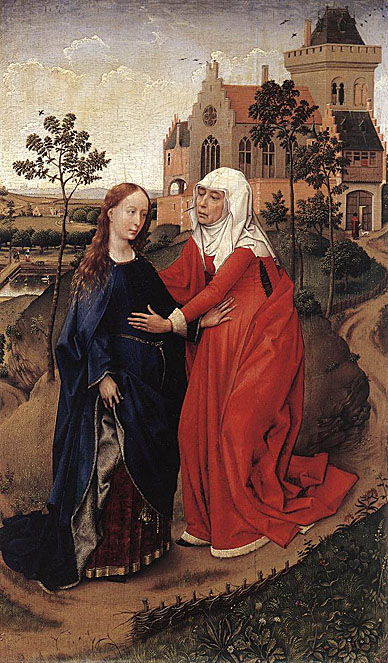

Rogier created another great work during his early period in Brussels, roughly between the middle of the 1430's and the beginning of the 1440's: the painting of Saint Luke Drawing a Portrait of the Virgin, known as the Saint Luke Madonna. Saint Luke the Evangelist was also the first Christian painter, and had painted the Virgin Mary from life. As a consequence he was the patron saint of painters and in many towns and cities was regarded as patron of their guilds. As a result, most of the major pictures of Saint Luke were destined for the altars of these communities; Rogier's painting was probably an altarpiece for the Brussels guild.

There exist several examples of this composition, identical apart from a few details, of which the one in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, since its restoration in 1932-33, is regarded by most art historians as the original (other examples in Munich, Alte Pinakothek, St Petersburg, Hermitage, and Bruges, Groeninge Museum).

These similarities of color and light show that Rogier must have seen the original version of the Rolin Madonna, and he can have done so only in Jan van Eyck's studio in Bruges before Chancellor Rolin collected the picture, which was for his private enjoyment only and so was not accessible to the public thereafter. The meeting in Bruges between the two men who were by now the greatest and most famous painters north of the Alps - perhaps they were already acquainted - cannot have taken place very long after 1435, and may well have been accompanied by a lively exchange of ideas. At any rate, Rogier as town painter of Brussels not only profited by his knowledge of the Rolin Madonna, he also obviously came away from Jan van Eyck with new ideas and sketches of other motifs, soon to be used in his own workshop.

In spite of the inspiration Rogier had gained from Jan van Eyck, his Saint Luke Madonna is an entirely independent depiction of the subject, and was to establish a new tradition. In a departure from earlier paintings of the subject, Rogier's saint is not himself painting the Mother of God but recording the silverpoint drawing. This corresponds to the practice of contemporary portraiture, and also emphasizes the spiritual significance of the picture more than the long, craftsman like activity involved in painting itself.

By comparison with other works by Rogier, the extremely picturesque qualities of the chiaroscuro in the Saint Luke Madonna are particularly marked. Perhaps the artist, impressed by this effect in the pictures of Jan van Eyck, used it here because the painting not only honored the saint but also stood for the painter's craft. In addition, Rogier was demonstrating another modern artistic achievement, and thus - whether in homage or in a spirit of rivalry - was referring explicitly to the other famous Flemish painter of his time. On the whole, however, he interpreted his model very much in his own way: where Jan's figures are embedded in a world of light and shade, Rogier's figures clearly claim more attention than the rest of the picture. The landscape in the Rolin Madonna seems to stretch backward forever, suggesting in its countless details the whole teeming fullness of the world. In Rogier's picture it goes no further than its immediately visible part, and is cut off by architectural features at the sides; similarly the inner room, open to the elements in Jan's painting, has acquired a ceiling in Rogier's painting. The small town in the background is animated by little figures (including a man urinating outside the town walls) but it is possible to count them all - what is a whole universe in Jan's painting here becomes a comparatively flat background for the figures, one that can be completely surveyed.

In those figures themselves, however, Rogier shows himself far superior to Jan van Eyck as an innovator. His Virgin is the quintessence of tender maternal love, simultaneously humble and proud; she is presented to the observer in such a way that (unlike Jan's Madonna) she is effective even without the context of the picture, and may be seen as typical of representations of the Virgin by herself. Instead of the masses of folds in Jan's painting, her garment in Rogier's version of the scene forms attractive calligraphic patterns. Saint Luke is not kneeling motionless before her, absorbed in his work, but is approaching gently like the angel of the Annunciation. Although he is seen in the act of kneeling, it does not jar on the viewer that he could hardly execute a portrait sketch in that attitude, since his activity is not emphasized for its own sake. Instead, his mobile, sensitive hands express both veneration of the Virgin and the intellectual aspect of portraiture. The saint is deliberately captured in a state between movement and repose, which could be the reason why, by comparison with those in the Rolin Madonna, the figures have changed sides: the direction of the saint's movement runs counter to the usual way of "reading" a picture (from left to right) and is thus inhibited - if Saint Luke were seen approaching from the left his movement would appear too emphatic.

There exist three other examples of this composition, identical apart from a few details, of which the one in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, since its restoration in 1932-33, is regarded by most art historians as the original (other examples in Saint Petersburg, Hermitage, and Bruges, Groeningemuseum).

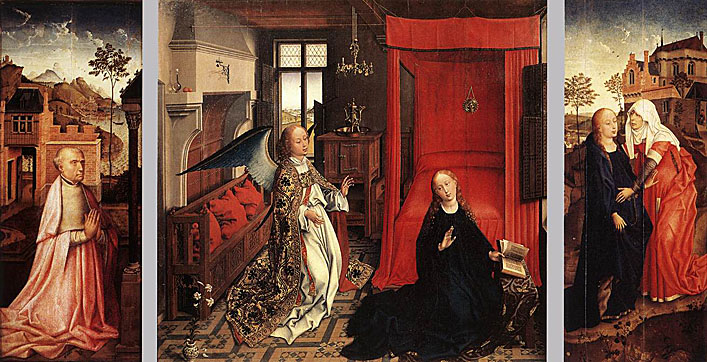

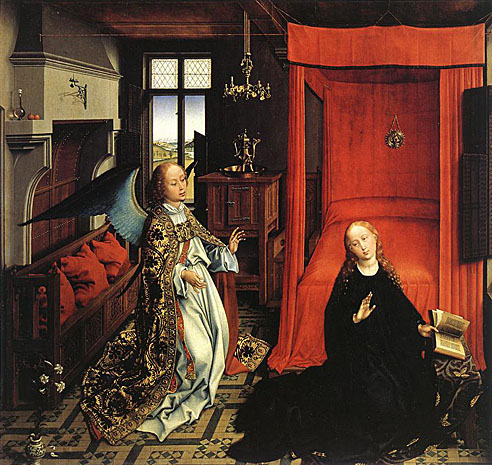

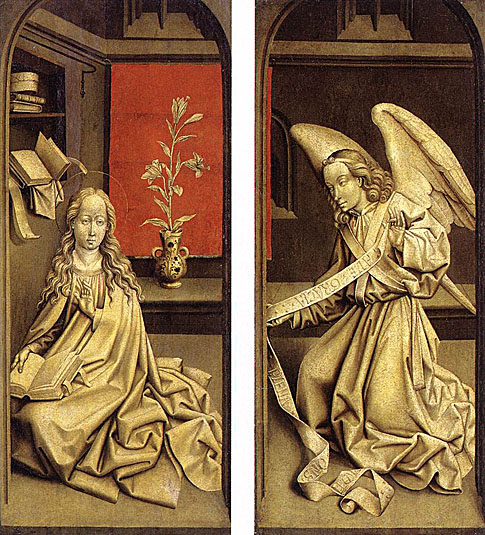

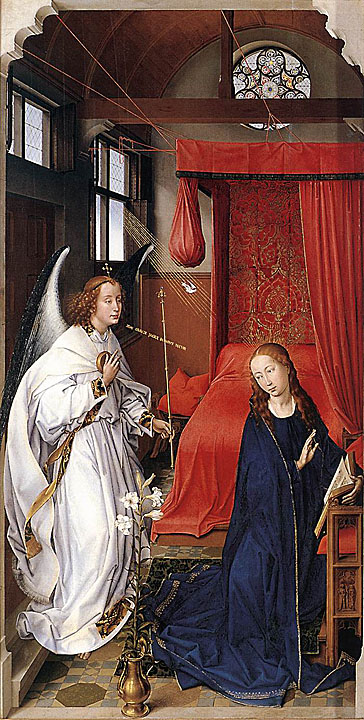

Chiaroscuro in the manner of Jan van Eyck is a prominent feature of the Annunciation that was originally the central panel of a triptych. Although the two wings of the altarpiece are not by the painter of the central panel, they try to achieve the atmospheric effects of light and shade seen in van Eyck's paintings.

The painting seems to have been designed to suit the Flemish taste for intimate domestic scenes, according to which painters were expected to portray religious themes in familiar bourgeois interiors. Yet, this does not derive from any concern for the minutiae of realist detail, but from properly theological reasons.

The new religious tendency in Flanders at that time was the "devotio moderna". This doctrine urged the believer to meditate on Christ's humanity, by representing it to himself in the context of his present life. In Rogier's painting, the contemporary setting, underlined by the absence of haloes, is meant to draw the viewer in so that he effectively participates in the scene before him. This is why the angel Gabriel appears before Mary dressed in an immaculate alb and magnificent brocade cope, as if he had come to celebrate mass, rather than deliver a message.

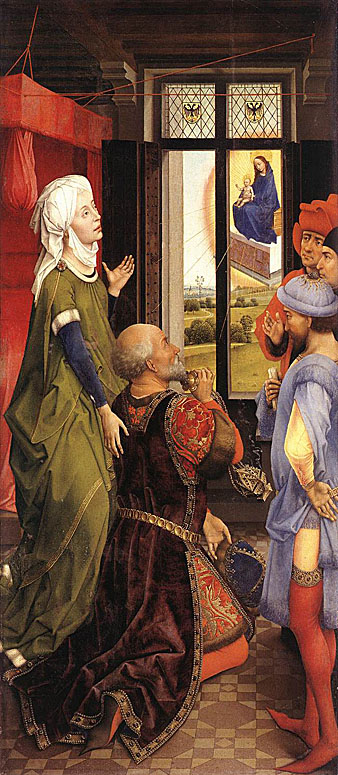

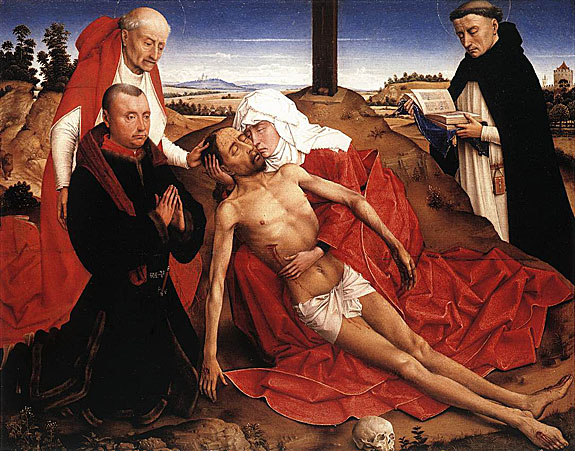

Rogier's position as town painter left him and his workshop at liberty to supply paintings to many other clients, both in Brussels and further afield. Around 1440 his fame had already spread well beyond the borders of the Netherlands. His name was known as far away as Spain, where King Juan II of Castile had founded the Carthusian monastery of Miraflores near Burgos in 1442, donating an altarpiece on the subject of the Virgin Mary by the hand "of Master Rogier, the great and famous Fleming." These details are mentioned in what is probably a contemporary record from the monastery, extant not in the original but in what seems to be a reliable copy made in the late 18th century. Fortunately, the Miraflores Altarpiece itself has been preserved as well as the record mentioning it.

_ca_1440.jpg)

In the Miraflores Altarpiece the painted architectural frames represent portals, and with their sculptural construction and tripartite form they are reminiscent of the portals of Gothic church architecture. Convincingly designed as they are in detail, they are not a realistic reproduction of any actual place, but are settings for scenes representing important elements in the relationship between the Virgin Mary and Christ rather than historical events.

On the left, the Virgin Mary is praying to the son on her lap; the central panel is a Pieta in which, Christ's body on her lap, she mourns His death and suffering; to the right, the risen Christ appears to her in order to end her grief. The reliefs in the archivolts, showing other events from the lives of the Virgin Mary and Christ, accompany and comment on these scenes. They provide much more extensive narrative than the main scenes, showing their context in chronological order, running counter-clockwise and beginning at the apex of each archivolt.

Color contributes a great deal to the complex programmatic content of the altarpiece. In contemporary painting of the time, and therefore in the work of Rogier, the colors of garments often convey meaning, but seldom so cogently as in the Miraflores Altarpiece. The color of Mary's clothing, which differs from one panel to the next, is not only aesthetically effective and diversified, but also makes a fundamental symbolic statement: white is for the purity of the Virgin, red for her pain, blue for her faith - virtues for which the angels hovering above, as the text on their scrolls indicate, are bringing her crowns.

The figures in the Miraflores Altarpiece are slightly more delicate and less powerful than those of the Deposition (Prado, Madrid), an impression reinforced even by comparison of the spandrels in the tracery. This difference may be to do with the much smaller size of the Mary altarpiece, but it corresponds to a general tendency in Rogier's development. Its change in figure style is accompanied by a change in the depiction of faces, which have become slightly more abstract and less lifelike. It seems probable, then, that the Miraflores Altarpiece was painted later than the Deposition. Art historians long assumed that it had been painted before the Werl Altarpiece by the Master of Flemalle, dated 1438, because the gesture of the right hand of John the Baptist in the left-hand wing of that work (Prado, Madrid) was assumed to derive from the depiction of the risen Christ in the Miraflores altarpiece. However, the under drawing clearly shows that the position of the hands was much altered in both figures during work on the paintings. Consequently, the artists must have been drawing on a common stock of workshop models to come up with their eventual solutions, and no chronological conclusions can be drawn. It seems most probable that King Juan commissioned the Mary altarpiece especially for his foundation of Miraflores, which would suggest that it was painted in the early 1440's.

_ca_1440.jpg)

_ca_1440.jpg)

_ca_1440.jpg)

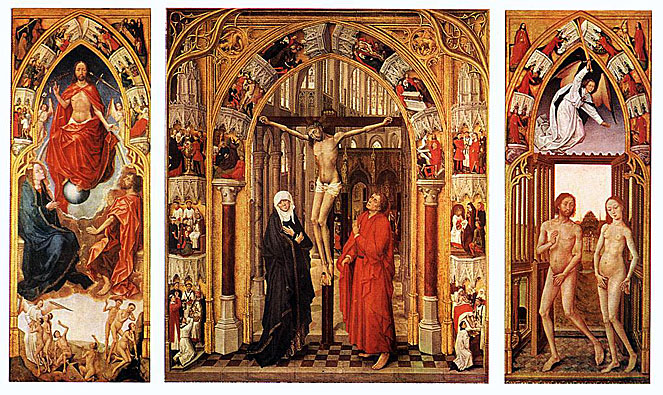

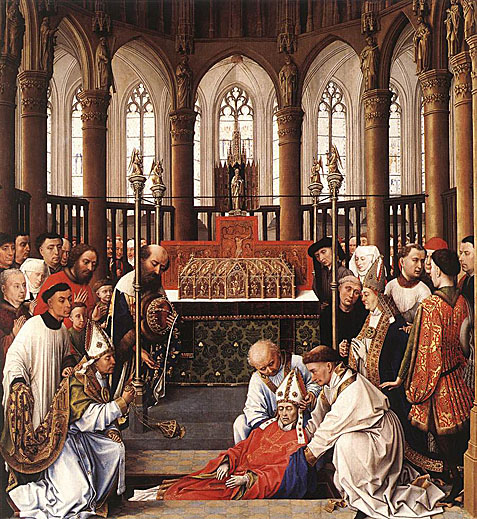

The Seven Sacraments Altarpiece was commissioned by Jean Chevrot, Bishop of Tournai (1436-1460) and one of the most important advisers of Duke Philip the Good. This powerful man is himself portrayed in the figure of the bishop performing the sacrament of confirmation to the left of the picture, and here looks very similar to his portrait in a miniature of 1448. Judging by the male fashions it shows, the Seven Sacraments Altarpiece may have been painted at about the same time.

Rogier's task was to show both the seven sacraments and also the Crucifixion, the fundamental act of redemption. He solved the problem by moving the separate actions into a basilica with three naves. The side aisles provide room for the sacraments, shown simultaneously; only the most important sacrament, the Eucharist, is taking place in the central section at the rood screen altar, which means that it is directly related to the sacrificial death of Christ.

We see an acuteness of observation in the Altar of the Sacraments. The Calvary sequence takes place in the interior of a light, spacious church, whose carefully executed details immediately catch the viewer's eye. The seven sacraments are presented around the central crucifixion group accompanied by an angel with a banderole. The importance of the action in the central panel is emphasized by the size of the depicted personages compared to the figures in the side panels. The emotion of the central characters - Saint John and the three Marys - who are overcome with grief, is a characteristic feature of Van der Weyden's art. It is thought that the triptych was commissioned in 1441 by the Bishop of Tournai, Jean Chevrot, for the altar of his private chapel. Van der Weyden portrays him on the left of the painting, as the bishop administering Confirmation.

Van der Weyden was probably helped by his assistants during the execution of the Altar of the Sacraments.

_1445_50.jpg)

_1445_50.jpg)

The sacrament of confirmation can be administered only by a Bishop and here it is being performed by the donor, Jean Chevrot himself. Several heads, obviously also portraits, were executed on small pieces of metallic foil or parchment, then stuck to the picture; they are, however, original. Possibly these portraits were done somewhere else, and then sent to the Brussels workshop to be added to the altarpiece.

_1445_50.jpg)

While the actions of the sacraments are accommodated in a church with some degree of plausibility - though a dying man's bed would not, of course, have been moved to a chapel for extreme unction - the Crucifixion group belongs to a different plane of reality, as is made abundantly clear by its much larger proportions, suitable to its significance.

At the same time, the artist tries not to make the difference seem disruptive, and with that end in view confines the large figures mainly to the central panel. If we look past them to the priest at the altar in the background, the difference of scale could be taken as perspective reduction. It is only to the left, where the cloak of the large figure of a female saint almost touches the priest performing the sacrament of baptism, that the problem seems not to have been entirely solved.

The church building with the sacraments here represents the church as an institution, but in its architectural details it echoes Saint Gudule's, Brussels' main church. The idea for the view into the depths at the back, seen at a slight angle through the central nave, came from a work by Jan van Eyck, his Church Madonna, probably painted around 1440 and now in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin. Working from this model, Rogier produced one of the most lofty and convincing church interiors of Early Netherlands' painting.

With its view into the main nave and side aisles, its great depth, and the more or less appropriate proportions of the smaller figures, it was the inspiration behind countless later Netherlands' church interiors, in particular those painted around 1600 in Antwerp. In dividing up the areas of the painting, Rogier - again following Jan van Eyck, in this case his Madonna Triptych now in Dresden used the triptych formula, but made some unusual changes to it: the lower side panels can no longer be folded over the central panel, and instead the outline of the entire altarpiece matches the building it portrays, with the inverted T shape also echoing a common feature of Netherlands' altarpieces, the raised center panel. Perhaps this idea came from carved retables, which are frequently raised in the middle and employ motifs of sacral architecture in their structural design.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Each sacrament has a side chapel to itself in this panel, so that the architecture a Gothic church ingeniously lies at the heart of the pictorial structure. The range of sacraments begins with the first to be performed in life, baptism, in the foreground of the left panel, and moves on to the last, seen here in the foreground. While the dying man receives extreme unction, his wife stands beside the bed with a candle to place it in his hand at the moment of death.

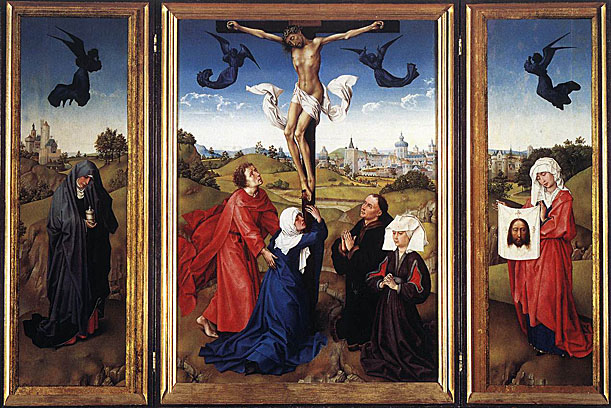

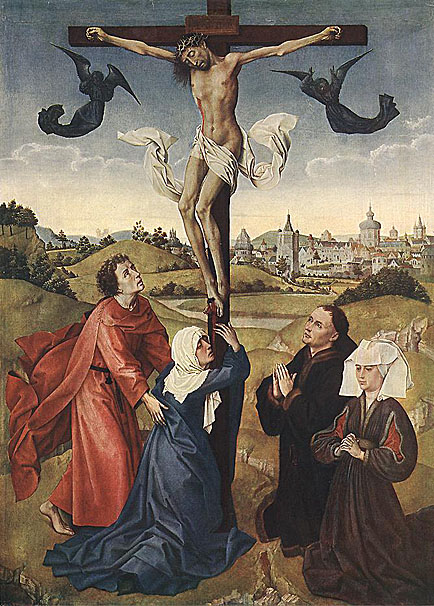

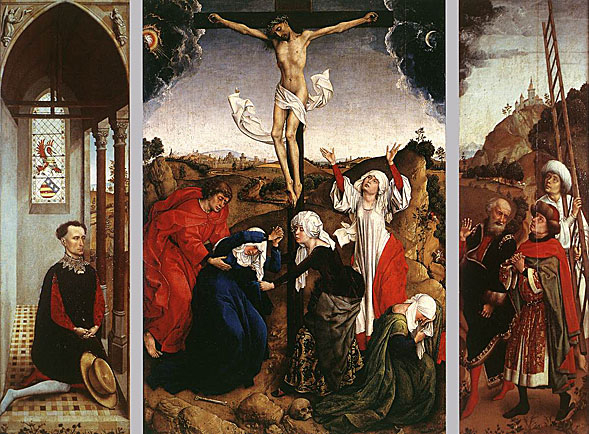

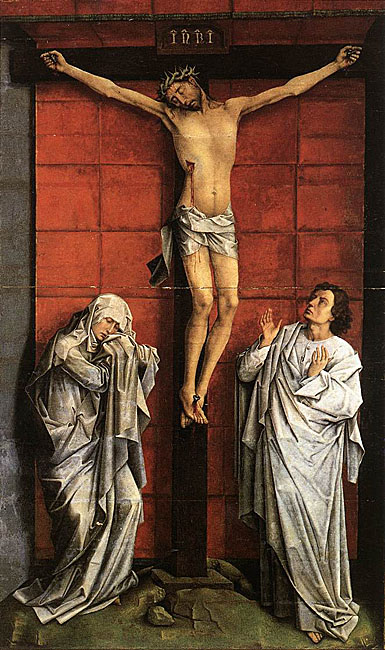

The Crucifixion Triptych, like the Seven Sacraments Altarpiece, is impressive in its composition. The two are linked not only by the use of a painted golden frame structure in the picture (not found, or not yet found, in any other surviving works by Rogier), but also in the style of the under drawing. Both works may have been created at roughly the same time, and the dating of the triptych to around 1445, on dendrochronological evidence, would support that theory. Certainly the designs of both pictures derive from Rogier himself, but his assistants seem to have been involved in the execution, and perhaps did some of the preparatory under drawing as well. The figures of the triptych are executed to a very high standard.

The Crucifixion Triptych, like the Seven Sacraments Altarpiece, is impressive in its composition. The two are linked not only by the use of a painted golden frame structure in the picture (not found, or not yet found, in any other surviving works by Rogier), but also in the style of the under drawing. Both works may have been created at roughly the same time, and the dating of the triptych to around 1445, on dendrochronological evidence, would support that theory. Certainly the designs of both pictures derive from Rogier himself, but his assistants seem to have been involved in the execution, and perhaps did some of the preparatory under drawing as well. T he figures of the triptych are executed to a very high standard. However, they seem more abstract and graphic and less three-dimensional than those in the great Deposition (Prado, Madrid), the Madonna in Red (Prado, Madrid), and the Miraflores Altarpiece (Staatliche Museen, Berlin). There is less play of light and shade, and although the landscape is crisscrossed by many rocky crevices and paths, it seems rather empty. Not a single blade of grass enlivens the foreground, and the view into the distance, with the town, also seems dry and lacking in atmosphere, in marked contrast to the artist's other landscapes.

The very emotional motif of the Virgin Mary embracing the cross is seldom shown; this dramatic reaction is usually reserved for Mary Magdalene. The Magdalene, however, has assumed a different role here: she stands to the left, entirely withdrawn into herself, more a separate figure than a participant in the event depicted. Curiously, she appears as a matron of fairly advanced years, while Veronica, also isolated in the other wing of the altarpiece, looks more like a Magdalene.

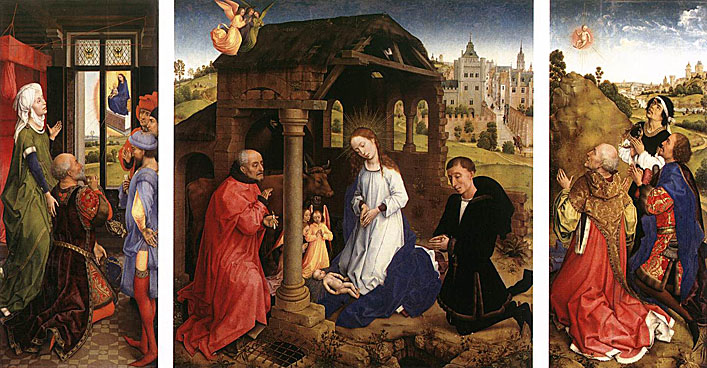

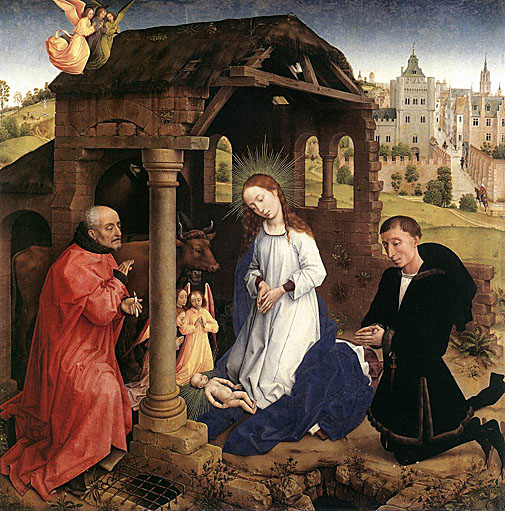

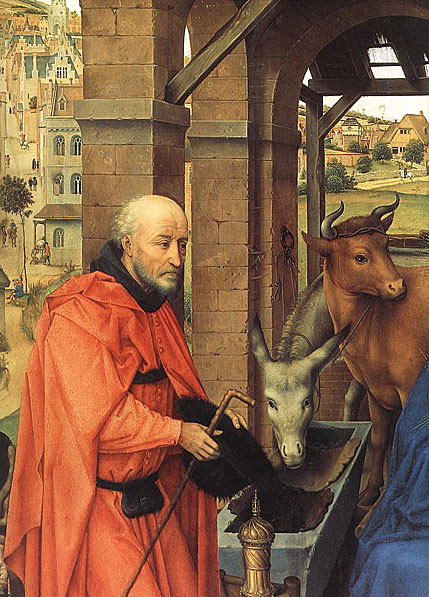

In the middle of the 17th century this triptych, known as the Middelburg Altarpiece, was in the Flemish city of Middelburg, founded by the rich Bruges burgher Pieter Bladelin and his wife around 1444. The donor of the work, also known as the Bladelin Altarpiece, is therefore usually thought to have been the founder of the city himself. On the other hand, Middelburg passed into other hands after the death of the Bladelins, who had no children, and there is no evidence that the altarpiece did not arrive there at a later date. Furthermore, it shows only one donor, although Bladelin's wife was cofounder with him of the new city. The donor depicted, wearing the same fashions as the Duke of Burgundy and obviously a member of the upper classes, must therefore be considered unidentified.

In the center panel the donor is shown kneeling in an attitude of prayer beside the Virgin and Joseph, adoring the naked Child. In the background is a town, perhaps representing Middelburg, near Bruges. The stable of Bethlehem resembles the ruin of a Romanesque chapel. The painter may have had in mind the remains of the palace of King David, who was reckoned among the forbears of Jesus. In the foreground the building is supported by a single pillar which bulks so large beside the tiny figure of the Child that it must obviously be regarded as symbolic. It can be interpreted both as a symbol of sublime power and of the place where Christ was later scourged.

The message of the center panel alone would be incomplete without the scenes portrayed on the two wings. The three panels together are an allegory of the world dominion of Christ and show not only the ruler of Middelburg and Brabant but also kings in both west and east paying homage to the Child. Tradition has it that, on the day of Christ's birth, a prophetess, the Sibyl of Tibur, showed the Emperor Augustus a vision of the Child and his Mother in the heavens. Here the ruler of the West (the Duke of Burgundy) falls humbly on his knees, removes his crown and swings a censer as a token of sacrifice. In the right-hand wing the three kings of the Orient are depicted; deeply moved and fearful, also kneeling before the vision in the heavens; this is the star of Bethlehem, which appears in the clouds with the embodiment of the Child, to guide them on their journey.

Not only in terms of the subject matter but also in the formal composition of the work, the painter has related the side-wings to the central scene. In so doing, he abandoned the uncoordinated scheme of the multipartite altarpiece familiar throughout the Middle Ages. One need only compare earlier works by Rogier van der Weyden such as the tripartite Altarpiece of Saint John the Baptist - to realize the extent of his advance. The bold use of space which the painter makes in each individual scene of the Saint John triptych becomes even more marked in the Bladelin Altarpiece, where the compass of the picture extends over all three panels, and this is also reflected in the abandonment of any dividing architectonic framework.

Rogier was one of the first great painters of the north to visit Italy. Around 1449/50 he must have been in Ferrara, Florence and Rome; and it would have been soon after his return from the south that he received Peter Bladelin's commission. There are few indications of Italian influence in the Middelburg Altarpiece. It is perhaps to be traced in the left wing, where the attendants, standing stern-faced and silent at the picture's edge, recall Quattrocento portraits in Florence.

Peter Bladelin (d. 1472), Treasurer to the Duke of Burgundy and founder of Middelburg, donated the altar triptych to the town church. It has been replaced by an early copy; the Berlin Gallery bought the original panels in 1834 from Nieuwenhuis in Brussels, who had previously purchased them in Middelburg.

The visions seen by these rulers are taken from a text popular at the time, but never previously illustrated in this form: the chapter on the Nativity in the Legenda Aurea (Golden Legend, a collection of tales of the saints written around 1270 by the Dominican monk Jacobus de Voragine (1228/29-1298). However, there were certain problems involved in illustrating it in realistic detail. It was particularly difficult to present Octavian's vision of the Madonna on an altar hovering in the sky, not borne up by angels or similar figures. Rogier solved this problem by seating the Virgin on an obviously heavy altar, so closely framed by the opening that she looks almost like a picture within the picture, providing an optical focus. The donor clearly wanted the text of the legend illustrated literally, and he must at first have asked for actual quotations too, although they were eventually omitted, to the benefit of the work as a whole: infrared photography shows that all the scenes originally contained scrolls to hold wording. The left-hand picture, for instance, was to quote the words miraculously heard by Octavian, according to the legend, on seeing the vision: Haec est ara coeli ("This is the altar of Heaven"). However, during the execution of the triptych it obviously became clear that the pictures would make their point even without any explanatory text, and the wording was over painted. Such a decision cannot have been taken without the consent of the patron who commissioned the altarpiece, and perhaps it may have been made during a conversation between Rogier and his client when the latter visited the artist's studio.

The donor of the Middleburg Altarpiece is more closely integrated with the scene than in almost any other Early Netherlands' painting. In his position and attitude he takes the place, within the Nativity narrative, of a shepherd praying, a motif frequent in pictorial tradition. Even in Rogier's Crucifixion Triptych (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), the married couple who commissioned the work are much more obviously outside the events shown, because their attitude of prayer cannot be seen as part of the narrative. But the donor of the Middelburg Altarpiece too is present only in spirit, witnessing the incarnation of God in his meditations. In order to put sufficient distance between him and the Virgin, the artist has resorted to a device already found in the Deposition (Prado, Madrid): the contours of his figure come very close to other items in the pictorial area, but overlap them to a minimal extent. The donor's head comes short of the ruined wall confining the area containing the Virgin, his hands are close to the outline of her dress but do not quite touch it, and the outline of his coat runs past Mary's robe with only a very slight overlap. The man is kept within a vertical area of the painting (an effect reinforced by the black he wears), an area also containing the fine town with its worldly bustle that is his real environment, although here, of course, it represents Bethlehem. The gap in the little wall behind the donor on the right denotes the road he has taken away from everyday life in his piety, an idea also suggested by the end of his head-dress lying on the ground.

A carefully calculated equilibrium is perceptible in the composition. There are three large figures on each panel - even the left-hand panel, where the emperor's two advisers at the back are in fact almost hidden by the one in front. The group around the Christ Child describes an upward-pointing triangle, balanced by a downward-pointing triangle created by the outline of the diagonally placed ruin and the two holes in the foreground, which are set on a slant. This surface pattern in the shape of a horizontal rhomboid, however, also creates depth, since the corner of the ruin projecting forward and the figures graduated in a sequence moving backward interlock spatially. But as usual, Rogier restricts the back part of the stage on which his main figures are set: the back wall of the ruin, the wall of Octavian's apartment, and the hill behind the Magi all act as visual barriers at about the same depth.

The main purpose of the triangular composition, however, is to emphasize the Virgin Mary, particularly since she is placed approximately on the central axis of the picture. This position might seem natural, but is in fact unusual in depictions of the Nativity, where Mary is generally placed to one side, next to the Child. The dark wall also acts as a contrasting background and forms a kind of baldachin over Mary. This manner of depicting the Virgin was another of Rogier's successful ideas, imitated by many other artists.

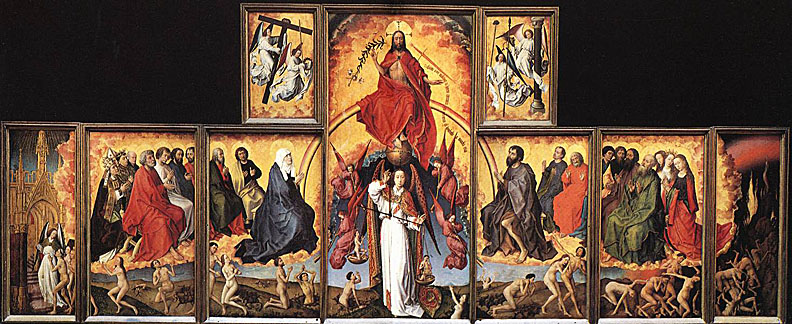

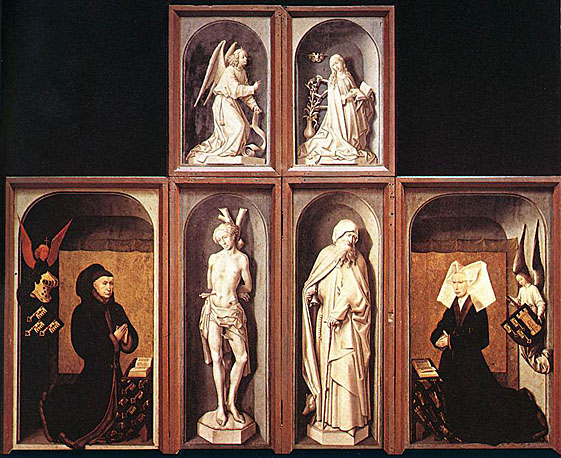

The Burgundian Chancellor Nicolas Rolin (ca. 1376-1462), one of the richest and most powerful men of the period, commissioned the Beaune Altarpiece for the hospital he had founded to care for the poor as well as the sick in 1443 in Beaune in the old Duchy of Burgundy, where the work can still be seen today. The altarpiece was intended for the chapel that stood at the end of the 72-meter-long hospital ward. The patients were to be able to see it across a partition, and its considerable dimensions and composition, clearly distributed over the entire surface of the picture and easily surveyed even from some way off, helped it to meet that requirement. Opened out, the retable shows the Last Judgment, a clear admonition to the sick to remember their own mortality and turn their minds to God. This is easily understandable, since the spiritual care of the sick was as important as their bodily care, and in the thinking of the time only those in a state of spiritual grace could be restored to health.

The enormous polyptych is made up of fifteen panels of different sizes. It was painted by Rogier Van der Weyden and his studio for the "great hall of the poor" in the Hotel-Dieu in Beaune. This hospital was founded by the fabulously wealthy Chancellor Rolin, and his devout third wife, Guigonne de Salins, for the salvation of their souls and in the hope of storing up treasures in heaven. Work began in 1443. The room was a vast open nave, with a paneled barrel vault for a ceiling, and could contain thirty canopied beds along its two long walls. The polyptych was placed at one end of this space, behind the altar, in a chapel separated from the nave by an "open-work wooden partition", through which patients could follow the divine service from their sick beds.

As long as the polyptych hung in the chapel, it was traditional to open the wings on Sundays and solemn feast days. But since it has been restored, it is now kept in a neighboring room which is air-conditioned to prevent any further deterioration due to the heat generated by the three hundred thousand visitors who come to see it each year. The panels were sawn in half across the thickness of the wood a few years ago, and both front and the reverse are now exhibited simultaneously, side by side.

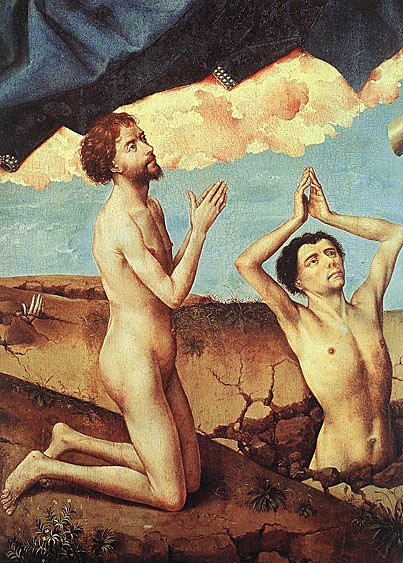

On either side of the central figures of Christ and the archangel Michael, the composition is built up on two levels. Above is a cloud of gold, on which are seated the apostles, judges in the celestial tribunal, as well as a pope, a bishop, a king, a monk and three women. Below them is the earth, from which the resurrected souls emerge, to go either to damnation or to eternal bliss. The central panel is dominated by the son of God, seated on a semi-circular rainbow; with the Virgin Mary at one end of the arc and Saint John the Baptist at the other. Christ's feet rest on a sphere, symbol of the universe. With his right hand, he blesses those who are saved and with his left curses those who are damned. These two gestures are emphasized by appropriate emblems, respectively, a lily and a blazing sword. Beneath Christ stands St Michael, prince of the heavenly hosts. He is pictured as young, because he is immortal and as handsome, because he is the embodiment of divine justice. He holds in his hands a scale in which he weighs souls. The souls are represented by two little naked figures, whose names are "Virtutes" and "Peccata". The former kneels, overcome with delight, while the latter seems horrified and screams with terror.

The lower tier depicts the elect and the damned. They are represented by two small groups of figures. They too are naked and are portrayed on a smaller, more human scale, than the saints above them. We see them propelled inexorably towards their fate. The damned are crushed beneath the weight of their sins. They have themselves painfully up out of the cracked dry earth, surrounded by sparks of fire and wisps of smoke. In contrast, on the opposite side of the polyptych, as one approaches paradise, flowers grow more and more abundant. In Van der Weyden's time, woman was regarded as a temptress and it was therefore more difficult for her to be saved than for a man - hence there are only two women in the group which, lead by an angel, are about to ascend to heaven. It was also believed that lunatics were possessed by demons. Here, the figures of the damned are tortured and deformed by hatred and their faces distorted by madness. Gripped by a collective hysteria, they are unable to weep, but instead scream and fight, as their folly draws them on towards eternal punishment. At the far left-hand side of the polyptych, paradise is represented as a gothic porch ablaze with light, the door that leads to the divine dwelling place. On the other side, hell is strangely lacking in devils. Instead, it is merely represented by a pile of dark rocks spewing flames and volcanic vapors.

The reverse of the panels of the polyptych depict the donors. Nicolas Rolin is an old man, whose nose is too long and whose hair has been cut short. Guigonne de Salins lowers her eyes and gestures with her joined hands towards her book of hours; on her head she wears a starched net veil. Behind each of them, an angel is carrying a shield emblazoned with their respective coats-of-arms. Rolin is facing towards an elegant imitation statue of Saint Sebastian executed in grey tint, as if carved from marble. His wife is looking towards another imitation statue, this time of Saint Anthony, who is accompanied by a young pig.

The donor of the Hospices de Beaune must have been an extremely powerful and wealthy man to finance such an undertaking. Nicolas Rolin spent nearly sixty of his eighty-one years in the service of the Dukes of Burgundy. For twenty years he was their legal advisor; he spent the remaining years as chancellor. A chancellor in the Middle Ages was a "super minister" combining the functions of Minister of Finance, Home and Foreign Affairs and others.

It is not surprising that a capable and intelligent man holding so much power and with more than half a century in the favor of one master, should amass considerable wealth.

And that master was no ordinary man. Philippe-le-Bon (Philip the Good), Duc de Bourgogne, Grand Duc d'Occident, could say without exaggeration that "I could be king if I so wished". He was a vassal of the King of France, but infinitely richer and more powerful than the unfortunate Charles VII.

Through a series of judicious marriages and annexation of lands after victories, the Dukes of Burgundy, from the days of Jean-Sans-Peur (Fearless John), built up vast spheres of influence, a patchwork of regions and races extending around the Kingdom of France in a crescent from just north of Lyons to just south of Amiens and from there to northern modern Holland.

Philippe-le-Bon entrusted the management of this vast domain to Nicolas Rolin. Certain chroniclers contend that his management was not entirely disinterested and that the magnificence of the Hospices directly reflects the degree of his remorse for his actions.

Nevertheless, it has been recorded that, assailed by criticism and reproaches and accused of misappropriation of funds, Nicolas Rolin, in order to silence envious tongues, appeared before Philippe-le-Bon dressed in the humble robes of a lawyer with a list in his hand and offered to return all the gifts which the Duke had showered upon him. The Duke refused this offer and was pleased that there was still room on this list for further gifts!

There was nothing to indicate that the Rolins, a modest family from Autun, were destined for such greatness. Nicolas needed unrelenting determination and persistence to successfully ascend the social ladder. As Councillor to Jean-Sans-Peur and, after 1422, Chancellor to Phillipe-le-Bon, Nicolas Rolin showed himself to be not only an able administrator but also a canny politician who succeeded in extricating the Duchy of Burgundy from an alliance with the English which became onerous after the glorious progression of Joan of Arc and the change in fortune of Charles VII. He was also one of the authors of the Treaty of Arras, the instrument which reconciled France and Burgundy and ended the Hundred Years' War.

Nicolas Rolin's pride and authoritarian nature are clearly reflected in the first words of the charter creating the Hospices, "I wish and hereby order... I wish and hereby devise that... ". In 1443, desirous of helping Beaune, the city of his mother's birth, recover from the devastation of the Hundred Years' War, Nicolas Rolin decided to build a hospital, "ignoring all worldly concerns and in the interests of my salvation ".

After the main outlines of his project were established, Rolin, enamored of the richness of Flemish architecture, imported an artist - thought to have been Jean Wiscrere - from the "flat country" to construct the Hospices in the image of the Hôpital Saint-Jacques in Valenciennes.

The Chancellor had initially calculated that the work begun in 1443 would take five years. In fact, the building was not dedicated until December 31, 1451. Nicolas and his wife, Guigone de Salins, welcomed six nuns from Flanders the next day and the first patient was admitted several hours later.

The last patient left the Hospices in 1971, 520 years later.

_1446_52.jpg)

_1446_52.jpg)

_1446_52.jpg)

One cannot fail to admire the delicate brushwork and coloring of the brooch holding the Archangel's cloak.

_1446_52.jpg)

_1446_52.jpg)

_1446_52.jpg)

_1446_52.jpg)

_1446_52.jpg)

_1446_52.jpg)

In line with traditional thinking, the dead have all risen at the age of 33, Christ's age when he died. The damned souls among them, crying out in despair, move of their own accord toward the fiery mouth of Hell. The limbs of the angular nude figures, still very Gothic in concept, create a complex interlocking pattern.

_1446_52.jpg)

_1446_52.jpg)

In Van der Weyden's time it was believed that lunatics were possessed by demons. Here, the figures of the damned are tortured and deformed by hatred and their faces distorted by madness. Gripped by a collective hysteria, they are unable to weep, but instead scream and fight, as their folly draws them on towards eternal punishment.

_1446_52.jpg)

_1446_52.jpg)

Rogier was at the height of his artistic powers when, in around 1455, he painted this altarpiece for the church of St Columba in Cologne. The Netherlands' artist not only created this work for a patron in Cologne, but also drew inspiration from an outstanding painting done in Cologne at this period, Stefan Lochner's Altarpiece of the Patron Saints of Cologne, sometimes known as the Cathedral Altarpiece.

The central Adoration of the Magi, the only depiction of this kind in Rogier's extant work, was a particularly popular subject in Cologne, for since the 12th century the city had kept relics of the Magi, its most treasured possessions, in the cathedral. The Netherlands' artist not only created this work for a patron in Cologne, but also drew inspiration from an outstanding painting done in Cologne at this period, Stefan Lochner's Altarpiece of the Patron Saints of Cologne, sometimes known as the Cathedral Altarpiece. This large retable, painted in the 1440's for the chapel of Cologne town council, unites the patron saints of the city in a magnificent, monumental work from which any trace of historical narrative has been eliminated. Rogier, perhaps at the special wish of his patron, adopted the almost central position of the Virgin Mary in the depiction of the Adoration; this was an unusual situation for her in Netherlands' art. He also echoed other motifs, including the figure of a woman seen in profile, dressed in green and with a plait of hair, who appeared on the left wing of Lochner's altarpiece and again in Rogier's Presentation; details like the sword and fluttering hatband of the youngest king; and, behind the Magi, the figure of a bearded man holding a hat in front of his chest. Traces of the late Romanesque church of St. Gereon in Cologne seem to have entered into the architecture of the temple on the right wing - the polygonal rotunda, the gallery, and the small buttresses on the outside.

Other than the adoption of motifs, however, there is little to link the Saint Columba Altarpiece to Lochner. As in the Middelburg Altarpiece, the panels are linked not by the background scene but by the lively sequence of figures all to the same scale, although the rotunda of the temple on the right does reach a little way into the central panel, where part of its exterior is visible. Compared with the earlier triptych, the figures are arranged in a shallower composition, not staggered back into the depths of the picture, an effect particularly clear in the second king. He looks two-dimensional, fitted in as he is between the other two, and although he is really further back the insistent red of his cloak brings him optically to the fore of the painting. The youngest king's white-clad page shows both how Rogier was composing his picture in two-dimensional terms, and how the narrow stage on which his protagonists are set is isolated from the background, which is crowded with motifs: the page is handing his master a magnificent vessel, but seems to be standing much too far back to perform the action. The page belongs to the background, which is not supposed to intrude into the foreground. Rogier clearly emphasizes the main figures inhabiting their own area at the front of the picture, an area inaccessible to the others.

Rogier developed many of these figures from older designs of his own. In the course of time Rogier must have designed a whole world of easily remembered figures and motifs, to be kept in the workshop's stock of models. He did not, however, use them mechanically, but always suited them to their new environments, so that without knowing the older pictures no one would take them for stock figures - something that is frequently not the case with his successors and imitators. However, the figures in the Saint Columba Altarpiece also differ from their predecessors in their nature. Their solidity and striking physicality has gone, they are more delicate and the slenderness of the figures makes their movements appear even more graceful and elaborate than in earlier works.

The workshop's participation in its execution did not affect the quality of this very successful altarpiece adversely. Rogier's second son Pieter (ca. 1437-after 1514), also a painter, was probably working in the studio at this time, and so perhaps was the young Hans Memling. Even the under drawing seems to have been done by an assistant working to the master's design, and several hands obviously took part in the painting; particularly striking is the face of the young woman on the right behind the scene of the Presentation, which deviates from Rogier's standard figures in type and in the more open, less enamel-like style of painting. The heads of the red-robed Saint Joseph on the central and right wings are different in both expression and formal structure, though they are almost entirely identical in their details; the two painters responsible must have been using a very precise drawing.

The impressive compositions of the Saint Columba Altarpiece, the grave and aristocratic figures, their slender delicacy, echoing the ideals of the time, and the many finely worked details made a great impression on Rogier's contemporaries. In the following period, his Adoration of the Magi was regarded almost as the only correct version of the theme, and not only the painters of Cologne but also other German and Netherlands' artists drew their inspiration from it almost entirely when tackling the subject.

The angel has entered Mary's chamber through a closed door and is speaking the words "Hail, thou that art highly favored, the Lord is with thee" in Latin, coming out of his mouth in gold lettering. With its tiled floor, stained-glass window, and the magnificent bed covered with extremely expensive gold brocade, the room is far from a humble dwelling, and seems more suited to a palace.

The composition of the central panel demonstrates a masterly balance between freedom and discipline. The Virgin and Child are shifted slightly to the left of the middle axis, which appears to run through the central pillar and down into the hat of the kneeling king. In fact, however, even these two details lie slightly left of centre. This left-hand bias is compensated by the figures of the second kneeling king and the third, youngest king, visually strongly accented by his expansively angled pose. The asymmetrical ruins of the stable correspond precisely to the composition of the main group. Insofar as Rogier arranges his figures from left to right in the style of a relief and orients his architecture parallel to the pictorial plane, he remains true to the principles underlying his Descent from the Cross. Here, however, he displays a more sovereign mastery of the organic structuring of the human figure and the partial creation of spatial depth.

The anachronistic little crucifix at the centre of the picture anticipates the purpose of Christ's life on earth, His act of redemption. The donor, with a rosary, kneels on the extreme left, divided from the rest of the scene by a small wall.

Traditionally, the three Magi represent the three ages of man: a youth, a mature man, and an old man. The youngest king is visually strongly accented by his expansively angled pose.

According to Mosaic Law, all firstborn sons had to be presented to God in the temple. When Mary and Joseph carried out this duty, the pious old Simeon recognized the child as the Redeemer whom, according to a prophecy, he was to see before he died. He thanks God with the words, "Lord, now let thou servant depart in peace, according to thy word." The old prophetess Anna, who also recognizes the Christ, is standing behind Simeon. The servant behind Mary is holding two doves for the sacrifice of purification that followed childbirth.

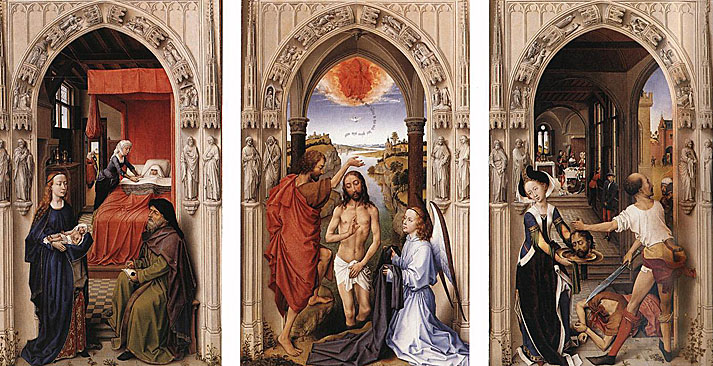

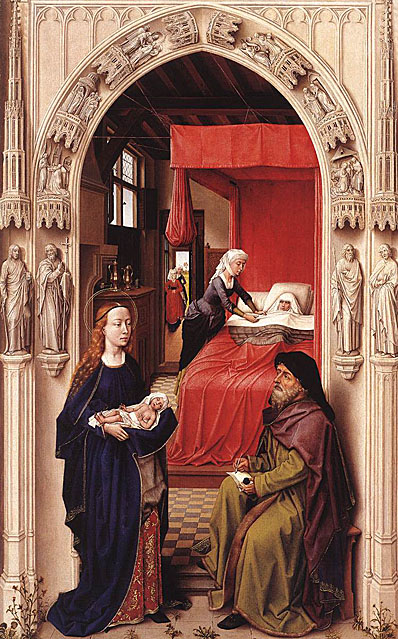

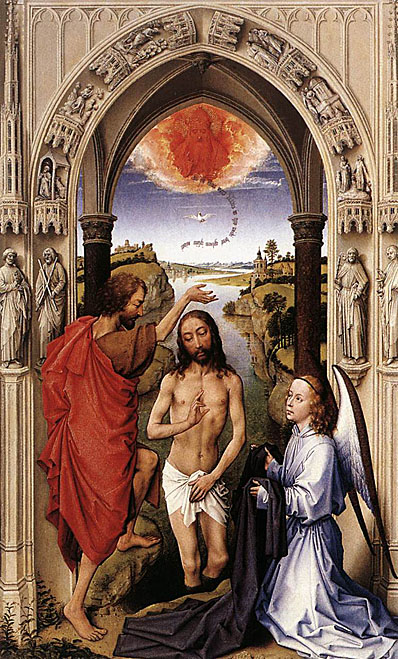

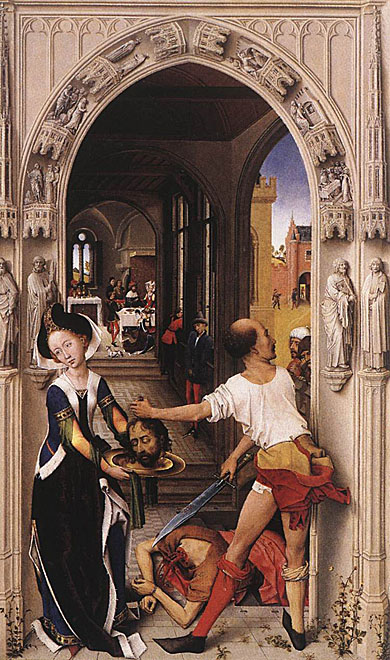

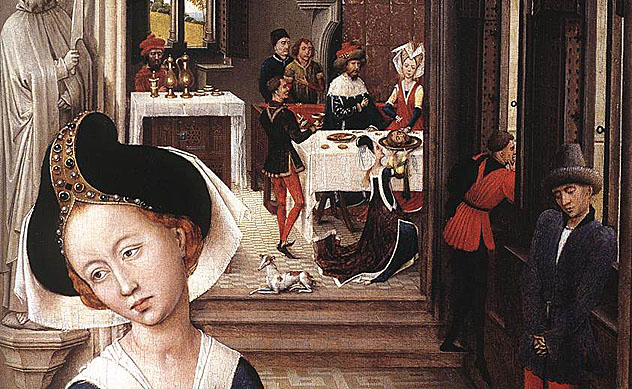

In the second half of the 1450's, not long after the execution of the Saint Columba Altarpiece, Rogier painted a smaller retable, probably intended for a side altar or a private chapel, the St John Altarpiece. It may be identical with an altarpiece by Rogier dedicated to John the Baptist and said to have been given to the church of Saint James, Bruges, by the merchant Battista Agnelli, a native of Pisa. The center of the retable shows John the Baptist baptizing Christ in the Jordan, with the naming of John to the left. In the scene of the beheading of John to the right, Salome is receiving the decapitated head after performing a seductive dance before her father - at her mother's instigation - to persuade him to order John's execution.

The altarpiece, like the much older Miraflores Altarpiece (also in the Staatliche Museen, Berlin), consists of three panels of the same size firmly mounted together in a frame. The work is not therefore a triptych, but an altarpiece that cannot be folded.

Van der Weyden constructed the portal to look like that of a real church. The grisaille paintings portray archivolt figures as well as saints in scenes which parallel the main motifs. The church facade is therefore not only a holy place, but also a pictorial element that sets the event firmly in a biblical context. At the same time, the spiritual world becomes accessible to the secular world: scenes appear from everyday life and the view gives on to a vista that includes a landscape and a town in the distance. It is here that van der Weyden's concept of art meets van Eyck's. The sacred fuses with the everyday and it is towards the latter that the holy events are oriented. The differences between the two artists cannot of course be ignored: while van Eyck's treatment of the contact between the sacred and the secular was free and light, van der Weyden insisted on a strict separation. The Saint John Altarpiece represents a new version of the Miraflores Altarpiece (Staatliche Museen, Berlin) in its pictorial construction. As in the Miraflores Altarpiece, three portals are decorated with relief and sculptural ornamentation, complementing the narrative content. Interestingly, however, parts of the real frame no longer run three-dimensionally across the panels, enhancing the plasticity of the painted architecture; instead, the impression is of a relatively shallow façade set slightly back. The main figures are on the same level as the portals, while in the Miraflores Altarpiece the space farther back is also opened up.

The shallow zone of the foreground is set off by the strong effects of depth in the side panels, where the rooms are almost like tunnels. This makes the narrative backgrounds of the left and right panels subordinate. The foreground and background areas are entirely separate in perspective too: as in the Miraflores Altarpiece, we have a full frontal view of the individual portals with the main figures at the front of them, so that the viewer might be standing directly in front of each panel. The backgrounds, on the other hand, are seen as if from a single viewpoint in front of the central panel, with the areas at the sides converging toward the middle and emphasizing the significance of the central event.

Elisabeth lies in bed in the background after giving birth, while the pregnant Mary, the future mother of Jesus, brings the newborn child to his father Zacharias. Zacharias had been struck dumb for his doubts when an angel told him, during service in the temple, that he was to be the father of a son (this scene is shown in the lowest archivolt relief on the left). He therefore has to write down the name of the child. Mary, as the more important saint, is distinguished from Zacharias and Elisabeth by her aureole.

The side panels of the Saint John Altarpiece do not merely show the beginning and end of the Baptist's earthly life. The parallels between the pictorial motifs also express moral conflict. On the left, the chaste Virgin Mary holds the newborn baby in her arms; she and Zacharias are looking at one another gravely, aware of the significance of the event.

In the central scene, Christ, hierarchically the most important figure in the whole altarpiece is brought as far forward as John the Baptist and the angels by the flatness of the painting, though he should be further back. The overlapping of figures is carefully avoided. Rogier paints an image of Christ, radiant and facing full front, which almost resembles an icon, while the figures to the side are set back from him. John, who is actually leaning to one side like the risen Christ in the right-hand panel of the Miraflores Altarpiece, appears much less three-dimensional than that figure, and his limbs are entirely two-dimensional. However, this attitude illustrates his action symbolically, and he is in harmony with the two-dimensional Christ, framed by the dark river as if in a mandorla.

As a lascivious worldly beauty, Salome wears a magnificent dress in the fashion of French princesses, with exotic decorative items including the pointed head-dress. The background shows the scene of the banquet in which Salome's mother, Herodias, stabs the decapitated head of the Baptist in her hatred for him.

The shallow zone of the foreground is set off by the strong effects of depth in the side panels, where the rooms are almost like tunnels. This makes the narrative backgrounds of the left and right panels subordinate. In the beheading of the Baptist, the body of the executed man is part of the foreground group, and the executioner can set his sword against John's right shoulder, shown in a flat plane. At the same time, however, two mourners who belong to the background are placed directly above the cellar stairs where the dead man is lying, and a figure diminished to about one-third of the size of the foreground figures appears to be standing only a little farther back from them.

The side panels of the Saint John Altarpiece do not merely show the beginning and end of the Baptist's earthly life. The parallels between the pictorial motifs also express moral conflict. On the right, the unchaste Salome, in magnificent and seductive clothing, holds the Baptist's head. She and the executioner are turning away from each other and from their victim, as if painfully conscious of the crime that has been committed.

Interestingly, however, the figure of Salome looks like a variant on the Virgin Mary in the Annunciation scene of the St. Columba Altarpiece (Alte Pinakothek, Munich), where the figure's knees are placed apart in an even more balletic position. Rogier was obviously able to make effective use of this elaborate and artificial pose in various circumstances, and only the worldly magnificence of Salome's dress and the context cause the viewer to assess it differently here. In addition, Salome's grave and melancholy face does not in fact differ much from the face of the Virgin Mary in that Annunciation, although in this later version it is leaning at rather too pronounced an angle to express grace. The artist has not set out simply to make the figure of Salome merely despicable; indeed, in the context of this scene, her noble features give her a touch of complex ambivalence.

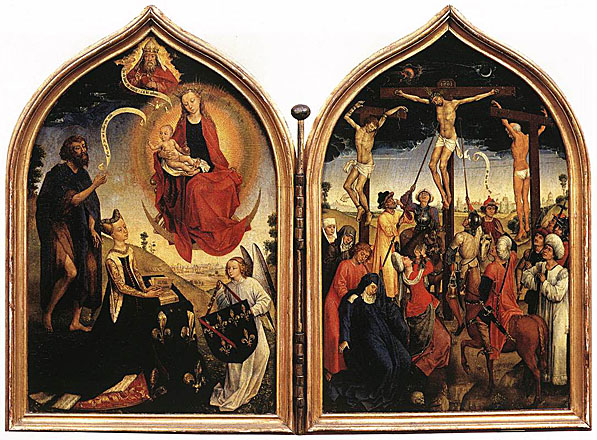

The busts of prophets on the outside of the Ghent Altarpiece by Jan van Eyck were the model for the bust of God the Father at the top of the left panel. The figures of Adam and Eve were from the same source. The picture is usually regarded as an early work by Rogier himself from the years 1432-35, but the figure of the Madonna is probably after Jan van Eyck's Madonna of the Fountain, dated 1439, in Antwerp.

The right panel is rather weaker, and is not by the same painter as the Madonna. As a king's daughter, Catherine has a crown, but she has taken it off, perhaps a sign of humility and reverence before the Madonna, and has placed it on the ground to lie there ignored. The wheel, her attribute, refers to the failure of the attempt to break her on the wheel; the martyr was finally beheaded with a sword.

Once again, the design of the triptych must have been by an assistant in Rogier's workshop. The figure of the red-robed Saint John to the left of the Cross shows how he reworked the master's figural types to suit his own ideas. The model is Saint John in Rogier's Deposition (Prado, Madrid), and it is followed faithfully in such details as the right foot. The folds of the robe, however, are more strongly modeled.

The cloak in particular, very dynamically draped and with a large fold flung backward over the shoulder, gives the figure a sense of agitation that is in tune with the character of this painting as a whole, but not with its model. Similarly, Mary Magdalene's cloak slipping down from her hips picks up a motif from the Deposition, but combines it with an extrovert gesture foreign to that picture, with the saint suddenly flinging up her arms.

The series of the three panels follows a chronological sequence: the sculptural Annunciation group in the donor's loggia refers to Christ's becoming man; in the central panel Christ has just died, and the sun and moon turn dark as His companions break into loud lamentations; on the right Joseph of Arimathaea, Nicodemus, and a servant are approaching with a ladder to take the dead body down from the Cross.

The left wing represents the Last Judgment, with the seven acts of mercy (six on the Gothic arch, the seventh in two parts at the upper left and right corners.

The right wing represents the Expulsion from the Paradise with the Temptation in the background. On the Gothic arch scenes of the Genesis are depicted. At the upper left and right corners are depicted God and the Creation of Eve, respectively.

Jeanne of France (c. 1435-1482), here being recommended by her patron Saint John the Baptist, was a daughter of King Charles VII of France (1403 -1461, king from 1422). The coat of arms shows her own crest with that of John of Bourbon, whom she married in 1452. The combination of the Crucifixion with the Apocalyptic Madonna (showing the Virgin Mary as the woman of the Apocalypse) is very rare. The work has some stylistic similarity to the Sforza Triptych (Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels).

_ca_1460.jpg)

_ca_1460.jpg)

Alessandro Sforza is kneeling before the Crucifixion at the centre - his head was painted on a separate piece of foil and then stuck into the picture - with two members of his family who cannot be identified for certain. On the same level, the wings of the triptych show Saint Bavo and Saint Francis on the left, and Saint Catherine and Saint Barbara on the right. The division of the altarpiece into two zones is very unusual: it makes the Nativity of Christ and John the Baptist in the upper area of the wings appear to be above rather than behind the figures in the foreground of the lower area.

_ca_1460.jpg)

The altar was donated by Michel de Chaugy, a Counselor of Philip the Good. The shrine in the retable shows carved scenes of the Passion; the donor's family, with its patron saints, occupies the wings. Stone figures of saints are depicted in niches on the exterior. In its construction, this work reflects the exterior of the Beaune Altarpiece.

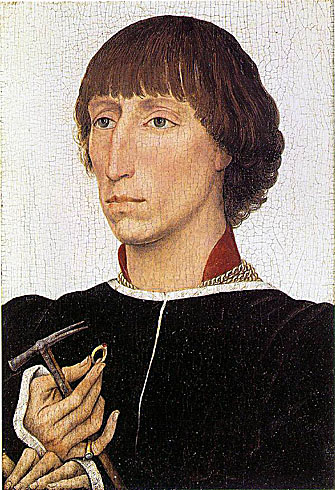

Among Rogier's portrait panels, those combined with a depiction of the Madonna to form a diptych constitute a group on their own. The subjects of the portraits are always on the right-hand panel of the diptych - which in the heraldic sense is the left-hand and therefore subordinate side. Consequently they are always turning left, toward the Madonna, and have their hands folded in prayer.

These portraits are constructed like the portraits of individuals except that their faces wear gentle and pious expressions as they gaze at the Virgin. None of these diptychs has been preserved as an entire unit, but two can be reconstructed with certainty (Portrait of Laurent Froimont in Brussels with the Madonna at Caen, and Portrait of Jean de Gros in Chicago with the Madonna at Tournai), and one experimentally (Portrait of Philippe de Croy in Antwerp with the Madonna in California).

The type of diptych consisting of half length figures of the Virgin Mary and the donor of the work seems in fact to have been developed by Rogier van der Weyden. Double panels on the same subject had already existed in the 14th century, but they always showed the figures full length. The new formula was based on head and shoulder depictions of Christ with Mary as intercessor, and they too had a long tradition behind them.

Rogier now replaced Mary by the donor of the diptych engaged in prayer, and in turn replaced Christ by his mother as the recipient of the donor's devotions. The result was to create a particular sense of closeness between the donor and the Virgin Mary with her Child, combining the large and ostentatious portrait with the theme of eternal prayer. This pictorial form proved very successful, and continued into the 16th century.

_1450_s.jpg)

This panel of the Madonna formed a diptych with the portrait of Jean de Gros; both have the donor's motto and emblem on the back. The painting has suffered from its poor state of preservation, and may perhaps be by a workshop assistant.

_1450_s.jpg)

_ca_1460.jpg)

A drawing (now in the Musee du Louvre, Paris) that was intended as the model for a painting is very closely related to the head of this Madonna that may have belonged to the Portrait of Philip de Croy (Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp); but as a whole she does not have the shape typical of Rogier, with its very high, domed forehead. Since the eyes are also very lifeless, and the dark, earthy color is not found in any of Rogier's works, this panel could be by another painter.

_ca_1460.jpg)

This painting is the right wing of a diptych. The left wing - now in the Henry E. Huntington Library, San Marino - represents the Virgin with Child.

Philippe de Croy (1435-1511) was a member of the most distinguished Burgundian nobility; in 1457 he was chamberlain to Philip the Good, he was administrator of Hainault in 1456-1465, and finally, in 1473, he became a Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece. He would have been about 25 in this portrait. Van der Weyden portrayed him as a refined and pious man. The fact that he is depicted at prayer supports the notion that this male portrait originally formed the right-hand part of a diptych.

_ca_1460.jpg)

_1460_s.jpg)

_1460_s.jpg)

_1460_s.jpg)

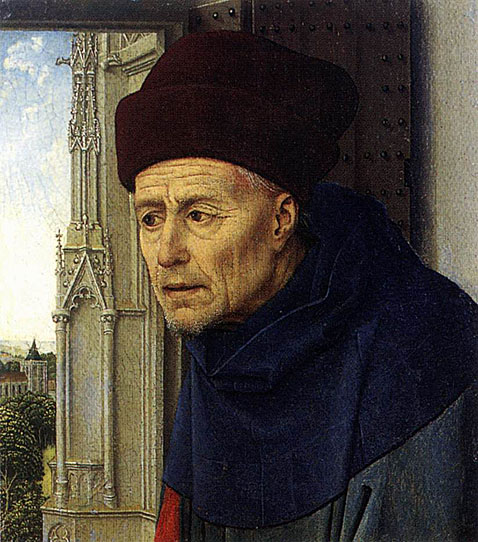

Rogier van der Weyden excelled in the genre of portrait. Unlike Jan van Eyck, he was no realist. He did not seek to capture the particular character of his model, but instead tried to create an ideal image. This approach was very popular with his contemporaries, and brought him considerable success in this genre. He was sought after by the grandest aristocrats and prelates, as well as by the wealthy bourgeoisie, who wanted him to record and embellish their features for posterity. Yet, depending on which historian you believe in, there are only between five and fourteen authenticated portraits by Rogier that have survived to this day.

Although he painted portraits throughout his entire career, many of them integrated into wider contexts and larger scenes, those of his individual portraits that have come down to us show a clear imbalance in their periods: the great majority were not done until the 1450's, and most of them were probably even as late as around 1460 and later.

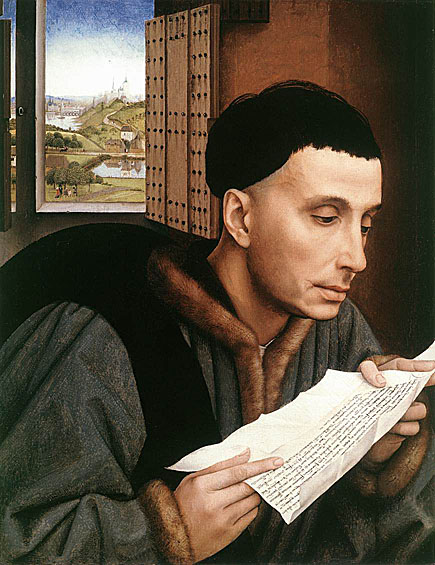

_1440_s.jpg)

_1440_s.jpg)

The young woman, with her expansive Flemish winged or horned coif of fine linen, through which the forehead remains visible, fills almost the entire panel. The 'nakedness' of the face and the softness of the features form an attractive contrast to the firm outlines of the stiffly folded linen and the dark background. The sitter's hands with ringed fingers are laid firmly on one another and rest on an invisible sill, support being provided visually by the frame.

While in his twenties the artist married Elisabeth Goffaerts, a native of Brussels and it has been generally assumed that she is the subject of the Berlin portrait. Although there is no real foundation for it, this is not an unreasonable assumption; the open, warmhearted expression seems to preclude an official portrait and to suggest someone close to the artist.

It was undoubtedly this impression of intimacy created in this portrait - it occurs nowhere else in the painter's work - which seemed to call for some explanation. To portray the subject looking directly at the viewer was something quite new when this painting was executed; in the Netherlands this technique occurs for the first time in van Eyck's portraits. The resemblance to the portrait of a woman by the Master of Flemalle (now in the National Gallery, London) is worth noting. The artist has modeled his subject with sympathy and sensitivity, while avoiding contact with the observer.

Several writers have drawn attention to Van der Weyden's treatment of his sitter's hands, which he almost always painted joined together, discreetly, so as not to distract from their faces, yet quietly present, always serving to underline their serenity.

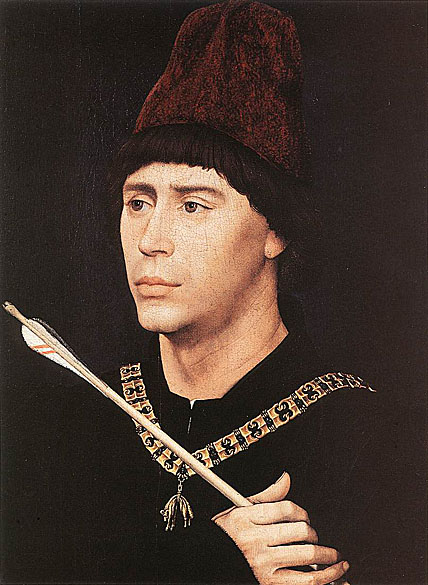

This painting is one of the several versions and copies of the portrait of Philip the Good executed by Rogier van der Weyden and his workshop.

The upright figure is enclosed in a diamond-shaped structure of diagonals, probably even clearer originally, when the slender body would have stood out in rather more contrast to the deep, greenish blue background, which has now darkened.

On the left, the wing of her head-dress forms a large diagonal line, continued in the patterned head-dress itself; on the right a rather shorter but broader wing of the head-dress balances the line, going the other way. Rogier has raised the woman's ear to allow a continuation of the line formed by the inner edge of this wing and her chin line. The effect is also to elongate her throat and neck, and the elegant line of the neck echoes the contour of her face on the left.

Another diagonal runs from the lower and narrower edge of the left-hand wing of the head-dress, over the outline of the woman's right breast - which hardly stands out at all from the background today - then to her left thumb, and on along her sleeve; the opening of this sleeve, in turn, lies along the same line as the plunging neckline of her dress.

These geometrical relationships do not merely provide pictorial structure; at the same time they lend the sitter a touch of austere dignity. They also emphasize an ideal expressed in the fashions that she wears: their slender, elongated elegance, the high forehead shaved at the hairline, the tall head-dress, and the low-necked, close-fitting dress pulled in below the breasts with a broad belt are all suited to that ideal. The large diagonals emphasize the slender upper body and the pointed culmination of the structure of the figure at the head, while the clear outline of the veil over her forehead makes her skull seem even taller by continuing the left-hand contour of her face, and finally sweeping elegantly upward into the head-dress. Beauty of line determines the features themselves, which are portrayed with fine, lifelike modeling. Their regular and immaculate structure, and the emphasis on such details as the sitter's large eyes and full, very sensuous lips, shows that although her portrait may well have resembled her, it is still an idealization.

The lighting, in contrast to the light of Jan van Eyck's portraits, is diffuse, and does not create the impression of a concrete spatial and temporal situation in which the subject of the portrait exists. This again is a kind of idealization, removing the woman in the portrait from all that is momentary and transitory. With the austere background, and her collected, deliberate attitude, which is complemented by the way her hands are placed together and her demurely lowered but alert gaze, she too expresses an aristocratic ideal of high rank - but this aspect of the portrait appears to be part of the woman's character rather than merely a pose. Rogier was probably faithfully reproducing the image that his sitter projected of herself.