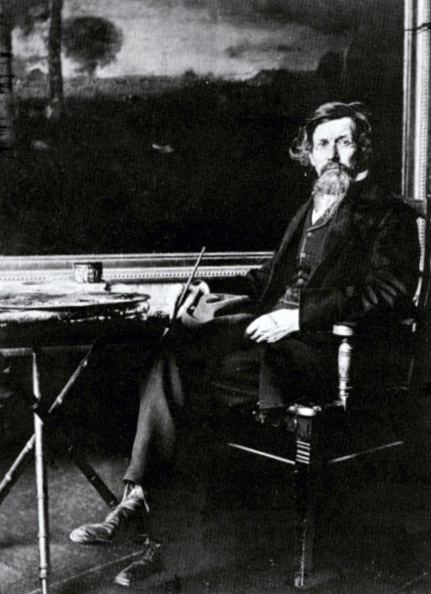

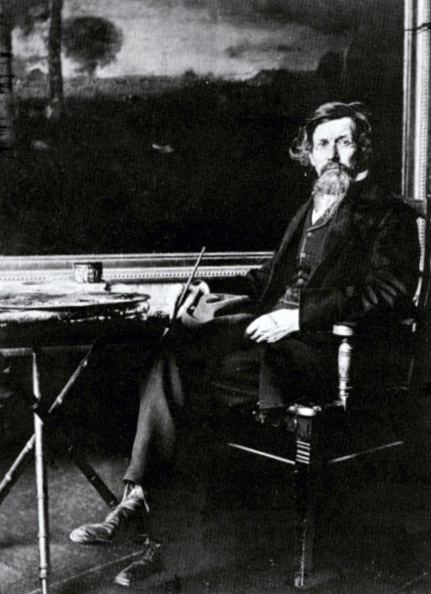

American Landscape Painter

1825 - 1894

~ George Inness

George Inness was an American landscape painter born in Newburgh, New York and died at Bridge of Allan in Scotland. His work was influenced, in turn, by that of the old masters, the Hudson River School, the Barbizon School, and, finally, by the theology of Emanuel Swedenborg, whose spiritualism found vivid expression in the work of Inness' maturity. He is best known for these mature works that helped define the Tonalist Movement.

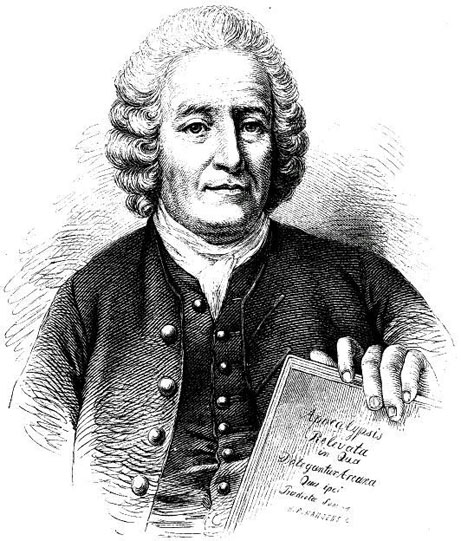

~ Emanuel Swedenborg

Inness was the fifth of thirteen children born to John Williams Inness, a farmer, and his wife, Clarissa Baldwin. His family moved to Newark, New Jersey when he was about five years of age. In 1839 he studied for several months with an itinerant painter, John Jesse Barker. In his teens, Inness worked as a map engraver in New York City. During this time he attracted the attention of French landscape painter Régis François Gignoux, with whom he subsequently studied. Throughout the mid-1840's he also attended classes at the National Academy of Design, and studied the work of Hudson River School artists Thomas Cole and Asher Durand; "If", Inness later recalled thinking, "these two can be combined, I will try."

Concurrent with these studies Inness opened his first studio in New York. In 1849 Inness married Delia Miller, who died a few months later. The next year he married Elizabeth Abigail Hart, with whom he would have six children.

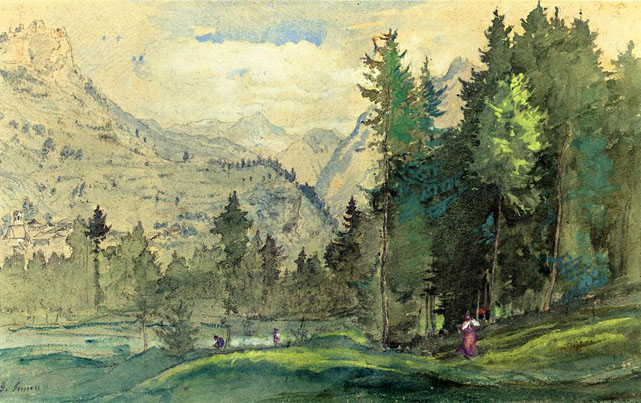

In 1851 a patron named Ogden Haggerty sponsored Inness' first trip to Europe to paint and study. Inness spent more than a year in Rome, during which time he rented a studio above that of painter William Page, who likely introduced the artist to Swedenborgianism.

During trips to Paris in the early 1850's, Inness came under the influence of artists working in the Barbizon School of France. Barbizon landscapes were noted for their looser brushwork, darker palette, and emphasis on mood. Inness quickly became the leading American exponent of Barbizon-style painting, which he developed into a highly personal style. In 1854 his son George Inness, Jr., who also became a landscape painter of note, was born in Paris.

In the mid-1850's, Inness was commissioned by the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad to create paintings which documented the progress of DLWRR's growth in early Industrial America. The Lackawanna Valley, painted ca. 1855, represents the railroad's first roundhouse at Scranton, Pennsylvania, and integrates technology and wilderness within an observed landscape; in time, not only would Inness shun the industrial presence in favor of bucolic or agrarian subjects, but he would produce much of his mature work in the studio, drawing on his visual memory to produce scenes that were often inspired by specific places, yet increasingly concerned with formal considerations.

This painting was commissioned by the Lackawanna Railway Company. At first, the painter, George Inness, was repelled by the idea since he did not regard technology as a suitable subject for landscape painting.

In the end, Inness undertook the project to see if he could produce a pleasant result, despite the distasteful subject matter.

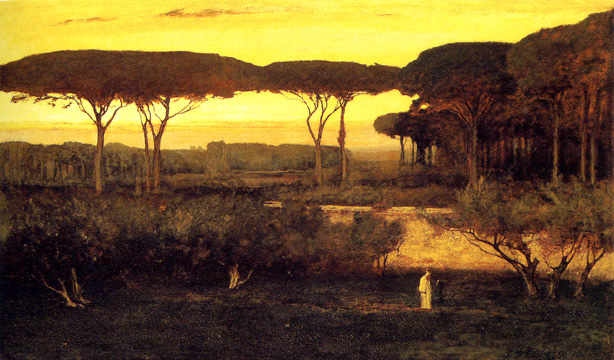

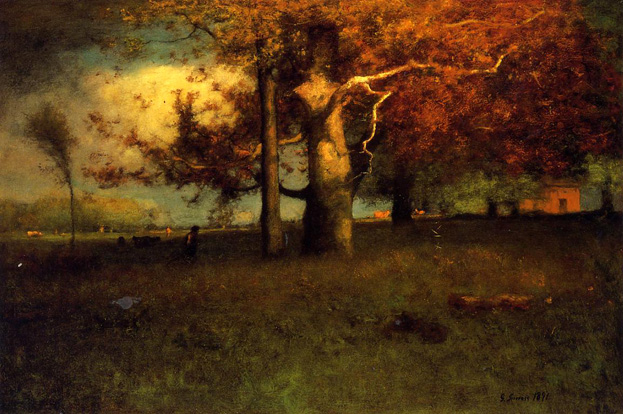

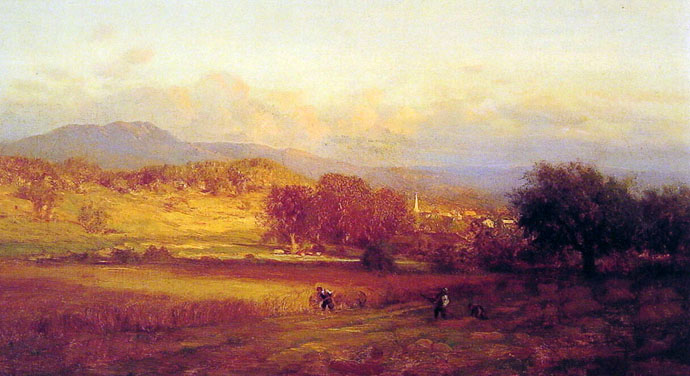

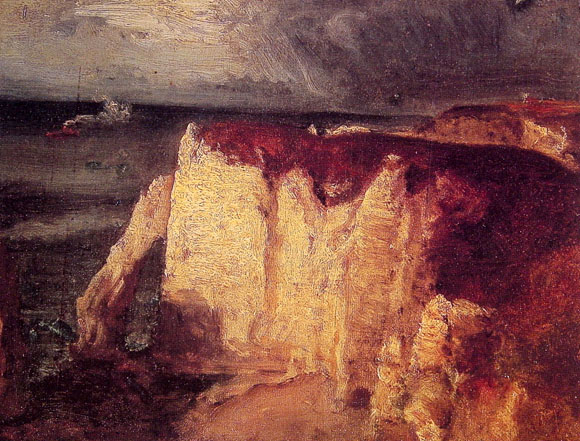

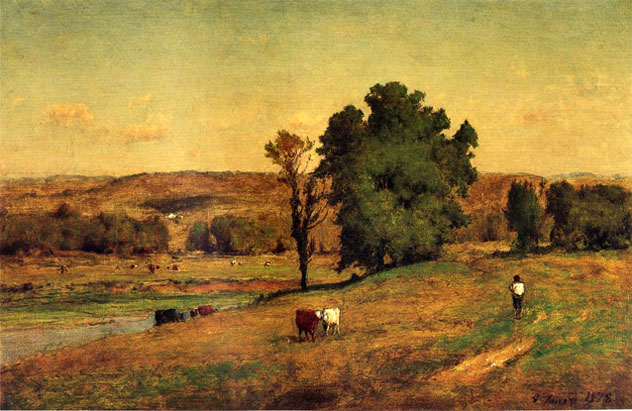

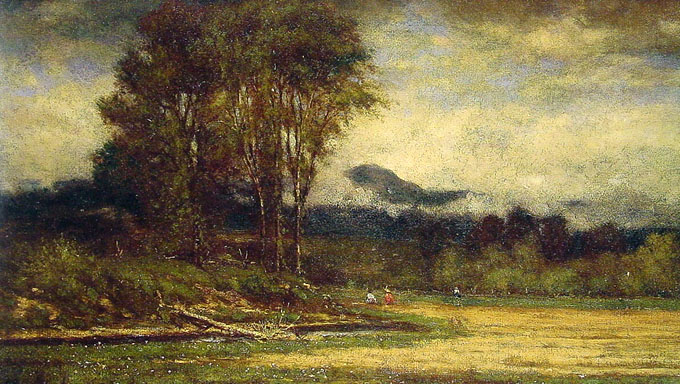

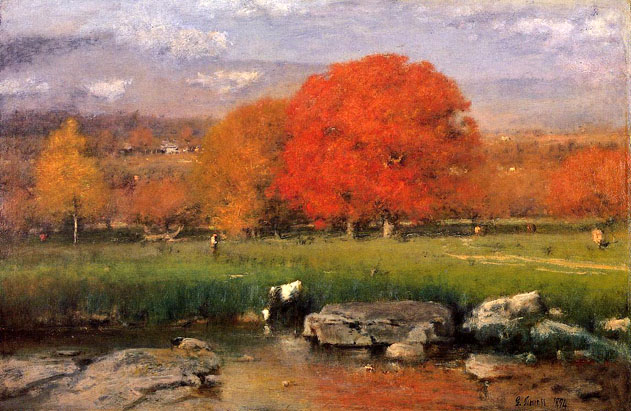

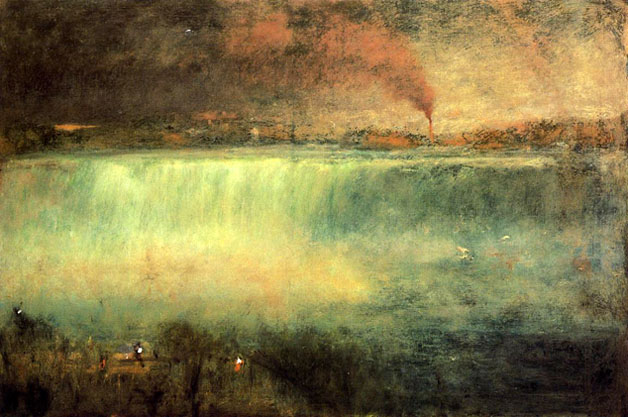

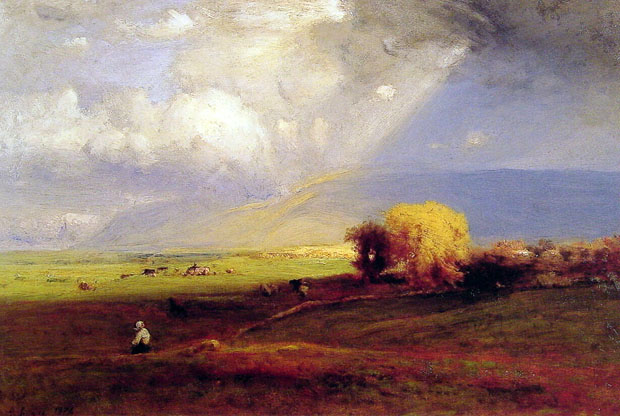

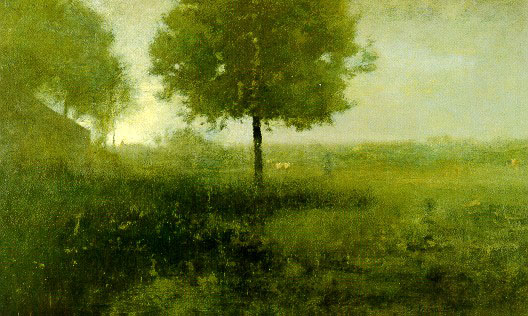

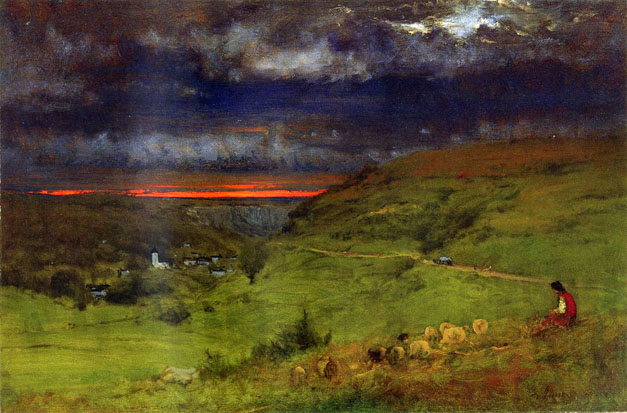

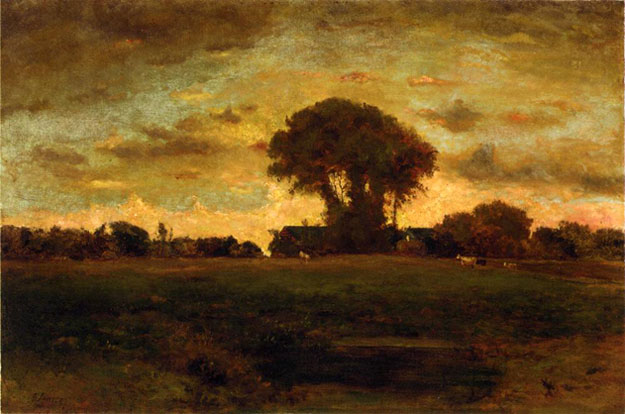

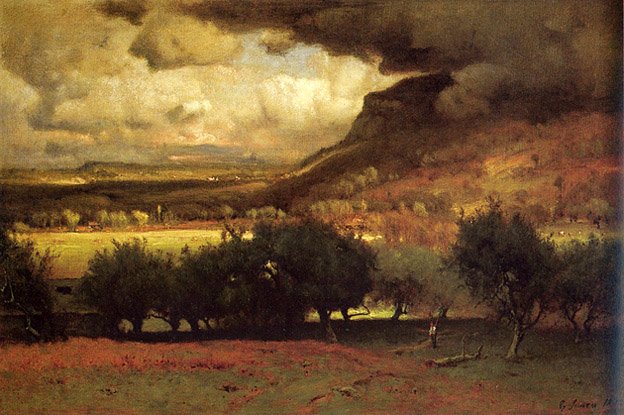

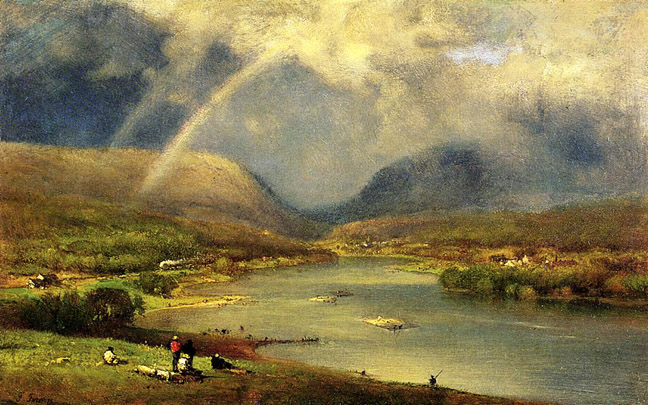

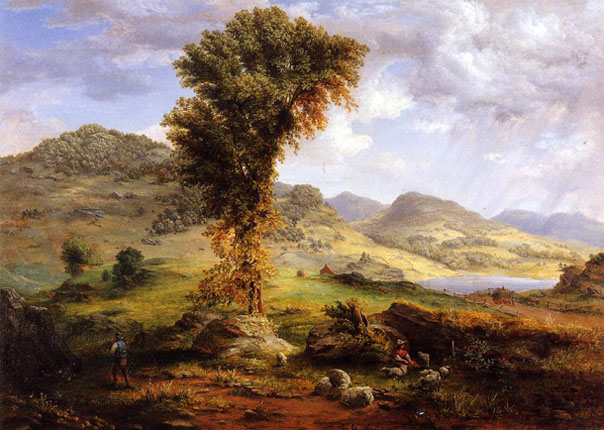

The work of the 1860's and 1870's often tended toward the panoramic and picturesque, topped by cloud-laden and threatening skies, and included views of his native country (Autumn Oaks, 1878, Metropolitan Museum of Art ; Catskill Mountains, 1870, Art Institute of Chicago), as well as scenes inspired by numerous travels overseas, especially to Italy and France (The Monk, 1873, Addison Gallery of American Art ; Etretat, 1875, Wadsworth Atheneum). In terms of composition, precision of drawing, and the emotive use of color, these paintings placed Inness among the best and most successful landscape painters in America.

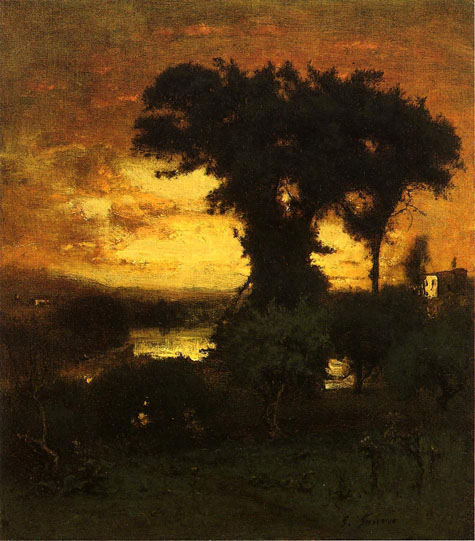

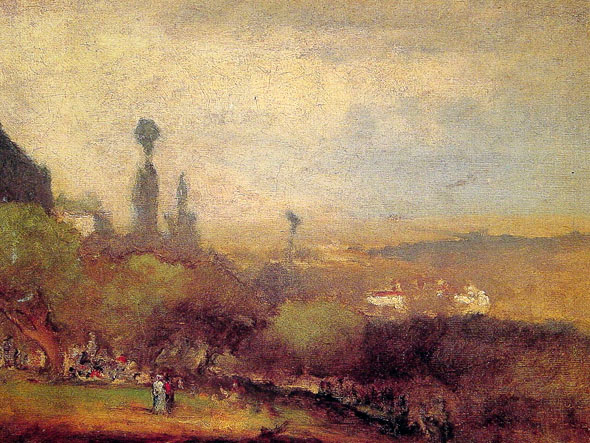

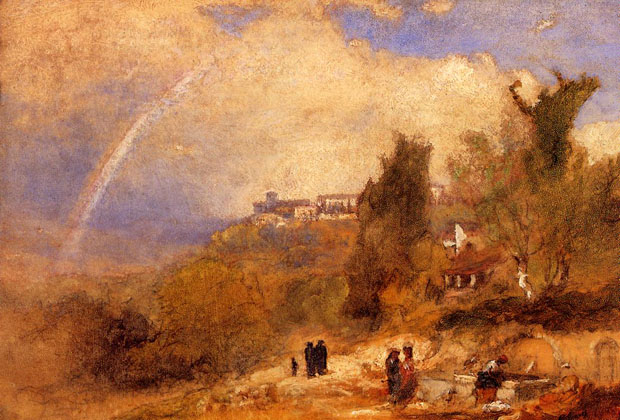

Inness chose one of the outstanding prospects of Lake Nemi from which to take his view. As early as the eighteenth century, artists such as Richard Wilson ("Lake Nemi," 1760, private collection) and Joseph Wright of Derby ("Lake Nemi, Sunset," 1790, Musée du Louvre) had painted the scene from nearly the same spot. Inness created a strong composition by portraying the scene in the morning light and filling the foreground with the dark, strong silhouette of the near side of the steeply sloped lake shore. He rendered the far side of the lake and sky in lighter colors, producing the effect of a hazy distant view.

Eventually Inness' art evidenced the influence of the theology of Emanuel Swedenborg. Of particular interest to Inness was the notion that everything in nature had a in a sense a correspondence relationship with something spiritual and so received an "influx" from God in order to continually exist.

Another influence upon Inness' thinking was William James, also an adherent to Swedenborgianism. In particular, Inness was inspired by James' idea of consciousness as a "stream of thought", as well as his ideas concerning how mystical experience shapes one's perspective toward nature.

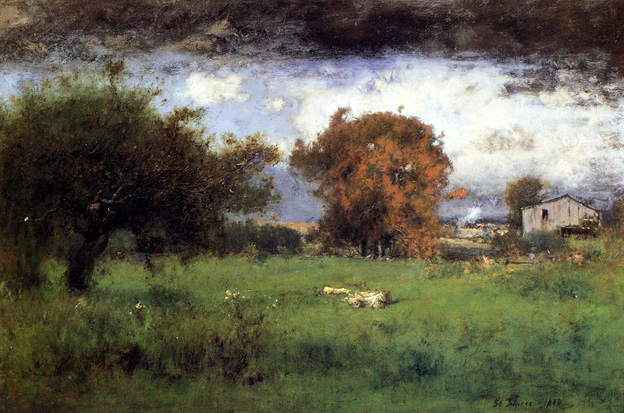

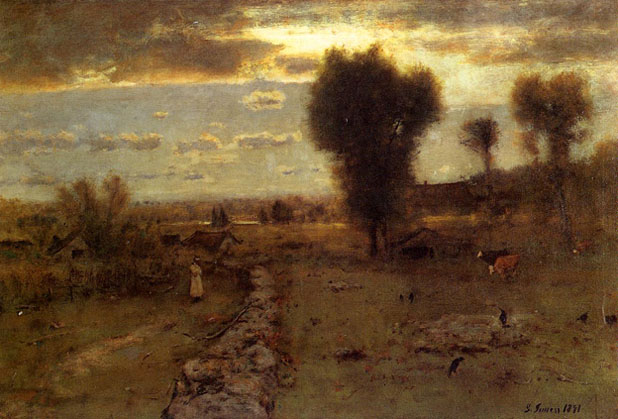

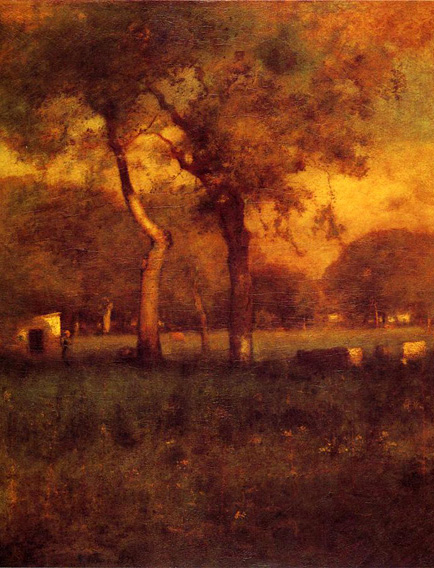

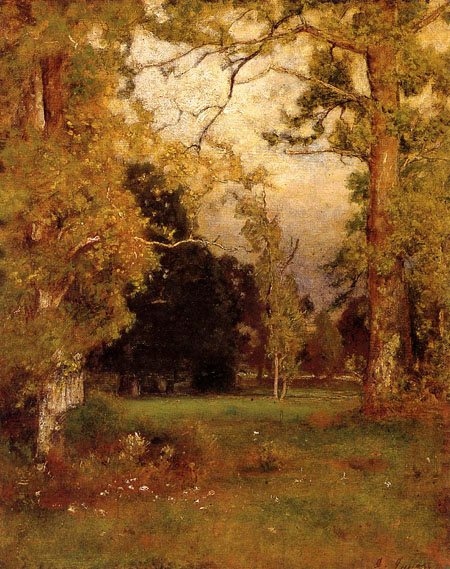

After Inness settled in Montclair, New Jersey in 1885, and particularly in the last decade of his life, this mystical component manifested in his art through a more abstracted handling of shapes, softened edges, and saturated color (October, 1886, a profound and dramatic juxtaposition of sky and earth (Early Autumn, Montclair, 1888), an emphasis on the intimate landscape view (Sunset in the Woods, 1891), and an increasingly personal, spontaneous, and often violent handling of paint.

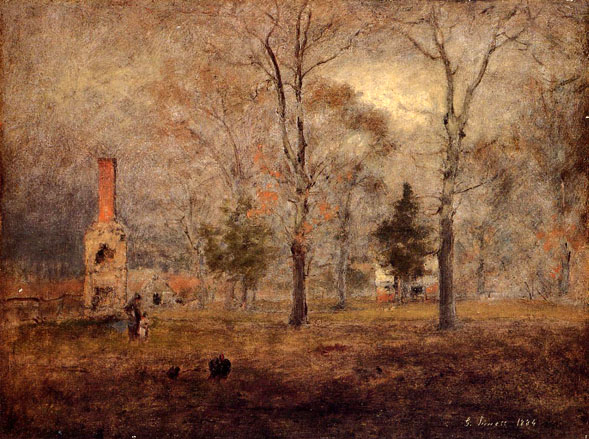

When listed in the catalogue of the executor's sale, this painting was entitled Near My Studio, Milton and dated 1882. Its similarity in technique and motif to paintings of 1882, such as June (Brooklyn Museum), does seem greater than its resemblance to most paintings of 1886.

The painting's most striking feature, its firm structure of horizontal and vertical elements and their careful balance, might on the one hand seem to favor the later dating, since this principle of synthetic composition is strongest in the works of the artist's final ten years. On the other hand, this concept first seems to emerge as a governing principle in his paintings of 1882.

The painting's very deliberate structure was advanced for 1882 and even 1886 and may be considered among the earliest works organized according to such a conspicuously geometrical scheme. It is cut into equal quadrants by the horizon halfway up the picture surface and the central vertical line of the gap in the trees and its corresponding reflection halfway across the surface. The trees are arranged at measured intervals to add a rhythm to this balance. It is noteworthy; however, that Inness shortened the tall tree above, perhaps to avoid the monotony of too close a symmetry.

It is this last quality in particular which distinguishes Inness from those painters of like sympathies who are characterized as Luminists.

In a published interview, Inness maintained that "The true use of art is, first, to cultivate the artist's own spiritual nature." His abiding interest in spiritual and emotional considerations did not preclude Inness from undertaking a scientific study of color, nor a mathematical, structural approach to composition: "The poetic quality is not obtained by eschewing any truths of fact or of Nature...Poetry is the vision of reality."

Inness died while in Scotland in 1894. According to his son, he was viewing the sunset, when he threw up his hands into the air and exclaimed, "My God! oh, how beautiful!", fell to the ground, and died minutes later.

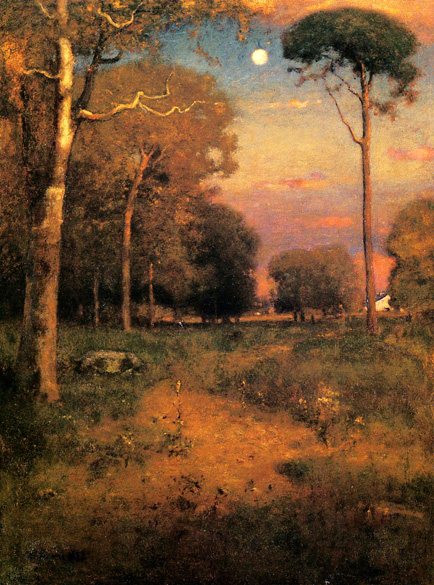

Between 1891 and 1894, Inness and his wife Elizabeth spent winters in Tarpon Springs, Florida. Shortly before his death, he produced a number of important works, among them Early Moonrise, Florida. The Museum's painting was created on his third visit to the state. It depicts the passage of the season and the movement of time through moisture-laden mists and vapors. The evening sky is filled with clouds of pink, blue, and mauve, which cluster low on the horizon and reflect the last pastel hues of the setting sun. A luminous moon shines from a bare patch of sky framed by tall, thin trees. Inness's works in general are the fullest expression of his devotion to the religious teachings of Emanuel Swedenborg, who believed that the earthly realm is a conduit for the heavenly one. In his late paintings, nature is suffused with spirituality.

If Catskill Mountains represents the early stages of Inness's integration of Swedenborgian Theological Themes into his art through the spare use of symbolic color, The Home of the Heron exhibits his spirituality and artistic style. Inness's use of atmospheric devices such as haze and mist to blur boundaries between earth and sky, treetops and clouds, unites the various landscape elements. Although he did not use any explicit Swedenborgian symbols in this painting, the seamless blending of the composition does suggest one of the religion's basic tenets: the unity and harmony of the universe reflects God's presence. By adopting modes of abstraction to convey spiritual associations, Inness successfully conveyed the otherworldliness of the Florida marsh at sunset.

The Home of the Heron appears to be influenced by Asian sources as well, although Inness, unlike many of his contemporaries, did not collect Japanese prints or ink paintings. Inness balked when critics grouped him with the Impressionists, the group of artists most closely associated with the influence of Asian art, but he may have absorbed Eastern sources through his religious experiences. Swedenborg borrowed from eastern religions, particularly Buddhism and Daoism, when conceiving his theological philosophy and assimilated into his doctrine their ideas about the relationships between man, nature, and deity. The artist's use of thin, black washes of paint that resemble ink and spacious, spare compositions punctuated by a deeply sensitive feeling toward nature certainly correspond to Asian brush painting. They may also correlate with Swedenborg's theological teachings.

Inness's musical sensibilities are also apparent in this work. As Nicolai Cikovsky has suggested: "In paintings like The Home of the Heron, proportion and measure, size and interval, seem carefully determined and exactly plotted. . . . Although we know that Inness was interested in mathematics and numerology, this was mathematics internalized as an instinctive, almost musical sense of rhythmic relationship, cadenced order, and melodic line." Early modernist painters such as Wassily Kandinsky and Georgia O'Keefe would incorporate such musical correspondences and inspiration into their work as well; Inness is not so much their progenitor as their distant and fondly remembered cousin. Early Morning, Tarpon Springs, another late Florida painting, exhibits similar religious and musical qualities. This painting, however, is oriented vertically rather than horizontally, and the landscape clearly is one touched by humans. Inness accommodated and accentuated the tall, gangly trees in his composition and allowed them to dwarf the houses built in their shadows. The lone figure dwindles in comparison to nature, yet, like the trees that surround him, he is not overcome by his marshy surroundings. The overarching tone of the painting is serene and contemplative; the landscape strange and sublime, but not threatening.

Florida was a place Inness visited during the last years of his life, and the experience of aging may have inspired the wistful poetry of his works done there. Sunset and sunrise seem to have preoccupied the artist during these years, and these subjects suit the suffused tone of the paintings. By painting exotic landscapes during his final years, Inness may have been preparing himself for death and its mystery; indeed, aptly, The Home of the Heron was re-titled The Sun's Last Reflection in an 1895 memorial exhibition of Inness's late work. A less romantic, more pragmatic interpretation is that because the artist was under contract to produce paintings up to the time of his death, he was forced to keep hard at work. Whatever the case, Inness's body of late work exemplifies both his need to apprehend the spiritual through painting and his continued desire to succeed professionally.

Inness's southern sojourns coincided with the last phase of his career and his achievement of a mature style. His paintings from the mid 1880's until his death are characterized by an expressive, loose transcription of nature through broad paint application and subtle color and tonal effects. In Gray Day, Goochland, pearly grays and molten pinks warm what would otherwise be a bleak winter scene of an adult and child walking across a field toward a farmhouse nestled in a thin cluster of barren trees. On the one hand, the painting perfectly captures the cool, muted light and the damp but nippy atmosphere of a Virginia winter. Yet, at the same time, the blurred forms and deep, yet paradoxically indefinite space convey a sense of the ethereal.

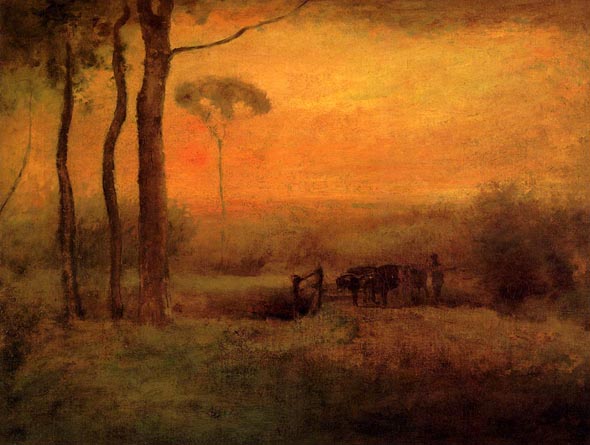

The Italian countryside held a special attraction for Inness. Preferring what he later called "civilized landscape" to the wilderness, as a young artist he painted landscapes reflecting the classical tradition. As his style matured, tight drawing and idealized scenes gave way to broader handling and a greater sense of atmosphere, light, and the expressive qualities of nature.

Because of its feeling of vivid, first-hand observation, Lake Albano relates more closely to Inness's Italian paintings of the 1870's than to his earlier American scenes. Some of his most daring color effects and pictorial compositions are found in his Italian landscapes. Lake Albano also shares with the later paintings a smooth, polished surface achieved through luminous glazes, as well as some picturesque elements and experimental pictorial effects, for example, the open spaces on the left side of the composition. While retaining the tranquility and deep space of the classical tradition, Inness abandoned the enclosing framing devices he used in his early works. Though classical landscapes usually included a few figures, Inness expanded this formula here, enlarging the figure grouping to a large gathering of contemporary figures engaged in a variety of activities.

In Moonlight, Tarpon Springs and a number of related paintings, Inness avoided the sights most frequently sought out by artists visiting Florida-alligators, palm trees, and lush flowers. Instead, he focused on the subtler flavor and atmosphere of the northern Gulf Coast, which is known for its tall pine trees, causeways, and short, flat vistas. Moonlight, Tarpon Springs reverberates with spiritual intensity. In the painting, the moon and glow of a distant bonfire pick out details in an otherwise dark and shadowy landscape that Duncan Phillips poetically described as having "the warm sweet gloom of our fragrant pine groves of the south." A lone woman in a white kerchief, who serves as both a compositional anchor and poetic accent, enhances the mystery and magic of the night. The figure and atmospheric effects are also reminiscent of the work of the French Barbizon School, an early influence for Inness. As Phillips observed, Inness was "inspired by [his] themes…possessed and acted upon by his subjects." And, in his late works, painted during the travels of his last years, he reached new heights of expressive interpretation of nature through the sensitive manipulation of color, composition, and paint.

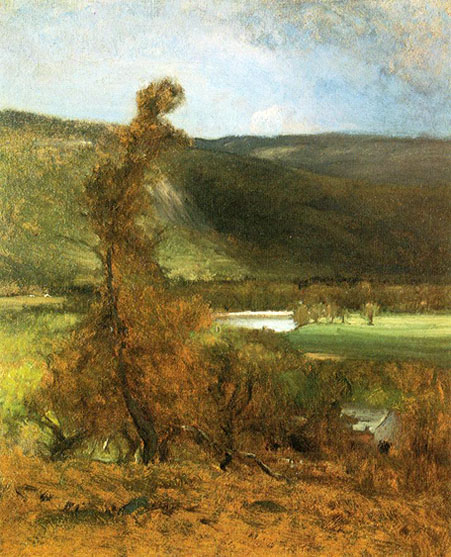

The train on the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western railroad, completed in 1855, steams towards us, in contrast to the raft moving slowly upstream. The view is from the Pennsylvania shore of the Delaware River. The further shore is in New Jersey. In the distance is the Gap, through which the Delaware cuts into the Kittatinny Mountains. This picture is the first of several versions of this subject by the artist.

Source: Art Renewal Center

Source: George Inness Online

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.