American Hudson River School Artist

1801 - 1848

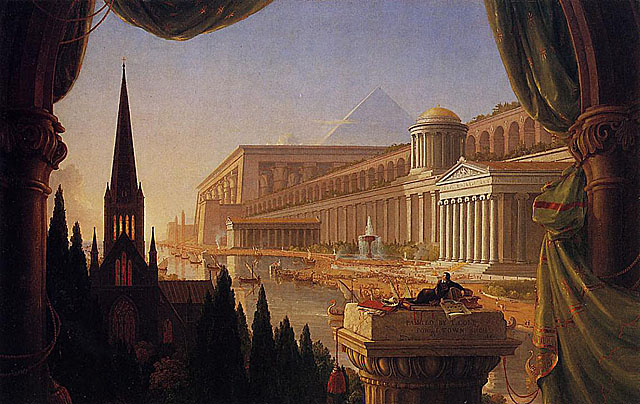

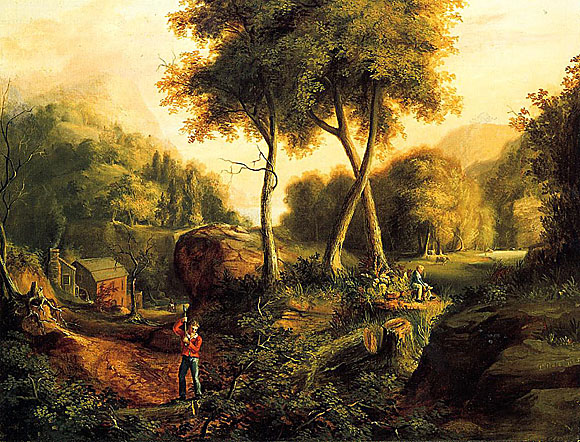

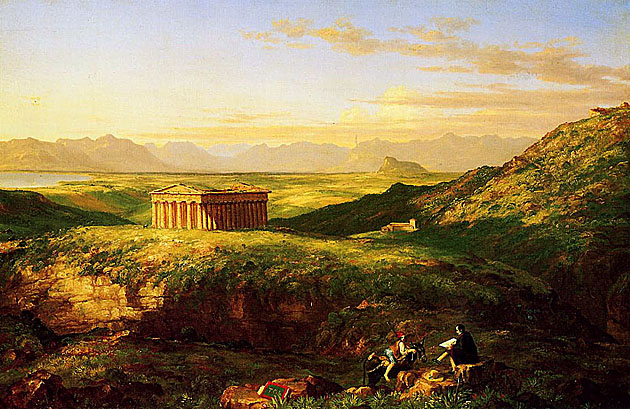

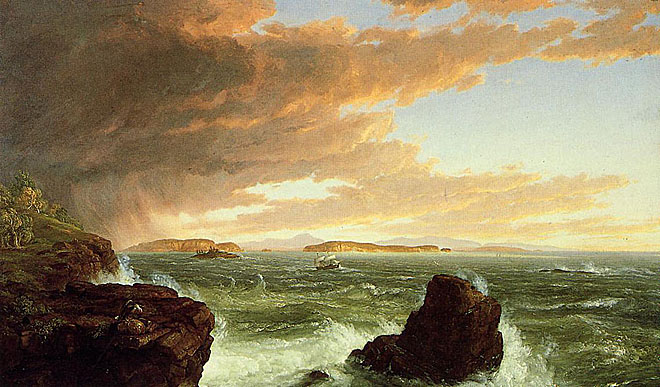

Thomas Cole was a 19th century American artist. He is regarded as the founder of the Hudson River School, an American art movement that flourished in the mid-19th century. Cole's Hudson River School, as well as his own work, was known for its realistic and detailed portrayal of American landscape and wilderness, which feature themes of Romanticism and Naturalism.

He was born in Bolton, Lancashire, England. In 1818 his family immigrated to the United States, settling in Steubenville, Ohio, where Cole learned the rudiments of his profession from a wandering portrait painter named Stein. However, he had little success painting portraits, and his interest shifted to landscape. Moving to Pittsburgh in 1823 and then to Philadelphia in 1824, where he drew from casts at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, he rejoined his parents and sister in New York City early in 1825.

In New York he sold three paintings to George W. Bruen, who financed a summer trip to the Hudson Valley where he visited the Catskill Mountain House and painted the ruins of Fort Putnam. Returning to New York he displayed three landscapes in the window of a bookstore; according to the New York Evening Post, this garnered Cole the attention of John Trumbull, Asher B. Durand, and William Dunlap. Trumbull was especially impressed with the work of the young artist and sought him out, bought one of his paintings, and put him into contact with a number of his wealthy friends including Robert Gilmor of Baltimore and Daniel Wadsworth of Hartford, who became important patrons of the artist.

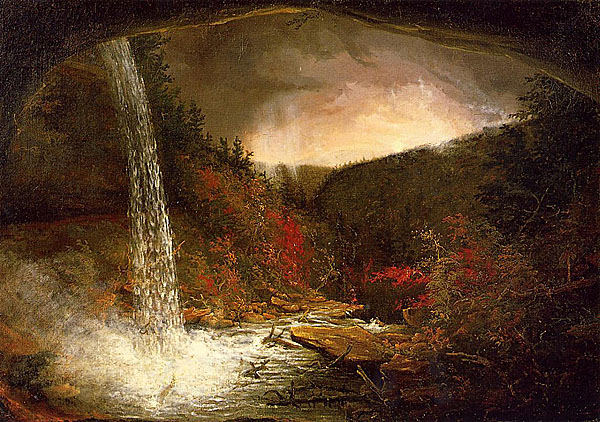

Cole was primarily a painter of landscapes, but he also painted allegorical works. The most famous of these are the five-part series, 'The Course of Empire', now in the collection of the New York Historical Society and the four-part 'The Voyage of Life'. There are two versions of the latter, one at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., the other at the Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute in Utica, New York.

Cole influenced his artistic peers, especially Asher B. Durand and Frederic Edwin Church, who studied with Cole from 1844 to 1846. Cole spent the years 1829 to 1832 and 1841-1842 abroad, mainly in England and Italy; in Florence he lived with the sculptor Horatio Greenough.

After 1827 he maintained a studio at the farm called Cedar Grove in the town of Catskill, New York. He painted a significant portion of his work in this studio. In 1836 he married Maria Bartow of Catskill, a niece of the owner, and became a year-round resident. He died at Catskill on February 11, 1848. The fourth highest peak in the Catskills is named Thomas Cole Mountain in his honor. Cedar Grove, also known as the Thomas Cole House, was declared a National Historic Site in 1999.

From: The Art Renewal Center

Often considered the father of American landscape painting as well as the founder of the Hudson River School, Thomas Cole immigrated to America from Lancashire, England, when he was age eighteen. After spending a year in Philadelphia, Cole joined his family in the town of Steubenville, Ohio. While in England, Cole had been an apprentice to a designer of calico prints, and in Steubenville, he found work drawing patterns and possibly engraving woodblocks for his father's paper-hanging business. In Steubenville, Cole also began to explore landscape painting after gaining some rudimentary instruction in oil painting from a portrait painter named Stein. In 1823, Cole went with his family to Pittsburgh, where he again became an assistant in his father's business and made landscape sketches in his free time.

Inspired by the landscapes of Thomas Doughty and Thomas Birch which he saw at the Pennsylvania Academy during a stay in Philadelphia from 1823 to 1825, Cole became dedicated to a career as a landscape painter. In Philadelphia, he began to consider the distinctive characteristics of American scenery, but it was not until he moved to New York in 1825 that he turned his thoughts to his art. The works he produced after a sketching trip up the Hudson River in the summer of 1825 attracted the attention of New York's prominent artists and patrons. From this time until the end of his career, Cole enjoyed fame as a pre-eminent American landscape painter, and created works that influenced a generation of native artists who followed his lead in focusing on the sublime beauty and grandeur of the country's wilderness scenery. In 1829, Cole became one of the founding members of the National Academy of Design, and departed on a trip to Europe. Traveling through England, France, and Italy, he viewed works by the Old Masters and contemporary artists and explored European landscape sites. A second trip to Italy, from 1831 to 1832, inspired Cole with ideas of exploring high-minded and grand themes. In landscape paintings he created on his return, he expressed the moral issues and lofty ideals that were usually the exclusive domain of history painters.

_1825.jpg)

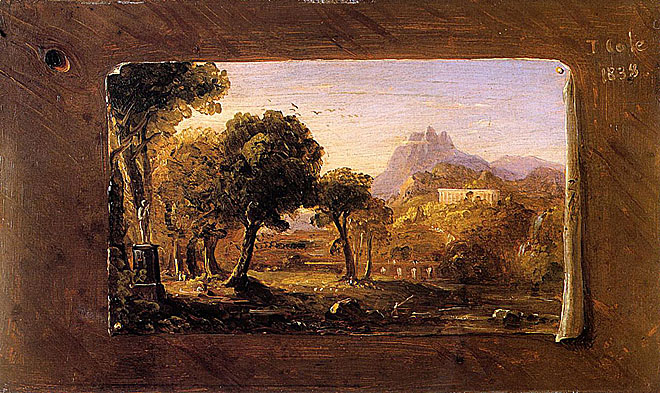

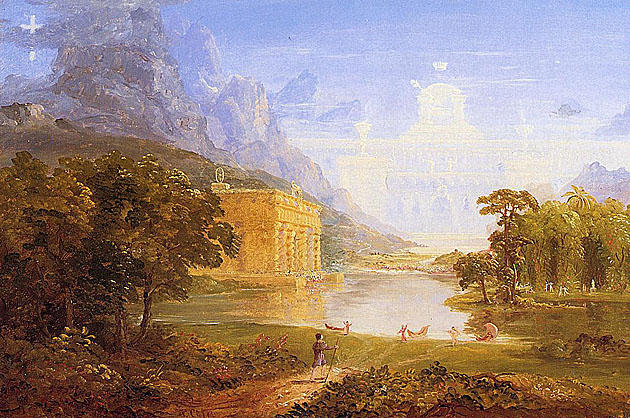

After his return to America, Cole settled in the town of Catskill, New York, but he remained active in the art scene of New York City, keeping ties with fellow artists and collectors. Among his acquaintances was the New York merchant, Luman Reed, who commissioned him to create The Course of Empire, (1836; New-York Historical Society), a five-canvas epic that depicts the cyclical development of a society from a savage wilderness to a grand and luxurious state, to a condition of corruption and destruction, and finally to dissolution. In the years that followed, Cole created both naturalistic views and imaginary scenes invested with moral or literary meaning. He rendered the two-canvas Gothic fantasy, The Departure and The Return (Corcoran Gallery, Washington, D.C.) in 1837 and the four-canvas religious allegory, The Voyage of Life (two versions, Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute, Utica, New York; and National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.) in 1840. Other allegorical landscapes include Dream of Arcadia, (1838; Denver Art Museum) and The Architect's Dream, (1840; Toledo Museum of Art).

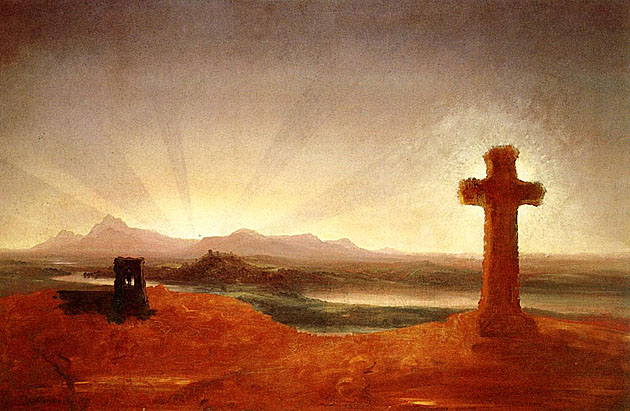

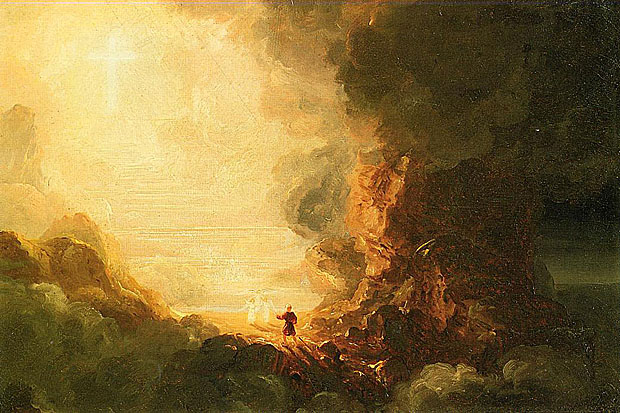

From the innocence of childhood, to the flush of youthful overconfidence, through the trials and tribulations of middle age, to the hero's triumphant salvation, 'The Voyage of Life' seems intrinsically linked to the Christian doctrine of death and resurrection. Cole's intrepid voyager also may be read as a personification of America, itself at an adolescent stage of development. The artist may have been issuing a dire warning to those caught up in the feverish quest for Manifest Destiny: that unbridled westward expansion and industrialization would have tragic consequences for both man and nature.

The dreaming architect reclines on huge books of building designs atop a monumental column inscribed with the artist's name and the name of the patron; architect Ithiel Town (1784-1844). Town was instrumental in popularizing the Greek and Gothic Revival architectural styles in America.

Despite the esteem with which Cole's allegorical works were regarded, some patrons preferred his identifiably American scenes. Cole was disappointed at this preference, but over the course of his career, he had steadily improved his landscape technique as may be seen especially in the works he created following his return from his second European sojourn, which demonstrated the impact of his exposure to European sources. Cole's pure landscapes demonstrate many of the principles and intellectual ideas reflected in his allegorical works. He expressed a romantic viewpoint, finding symbolic meaning in nature. As he wrote: "A scene is rather an index to feelings and associations."

In addition to his activities as a painter, Cole was a prolific poet, writer, and theorist. He kept many journals and wrote poetry and essays, including his well known tract on American scenery of 1835. Although his only student was the painter Frederic Church, Cole had an influential role in the New York art community, and fostered the careers of many Hudson River School artists. He was especially close to Asher B. Durand. Cole's unexpected death in 1848 at the young age of forty-seven was deeply mourned in New York art and literary circles. Both his art and his legacy provided the foundation for the native landscape school that dominated American painting until the late 1860's.

_1832.jpg)

_ca_1827_28.jpg)

_1832.jpg)

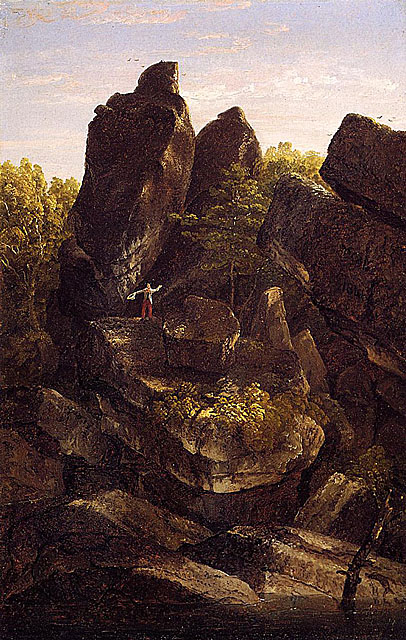

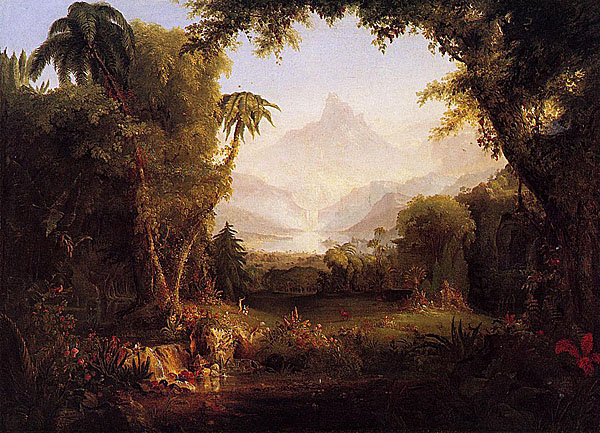

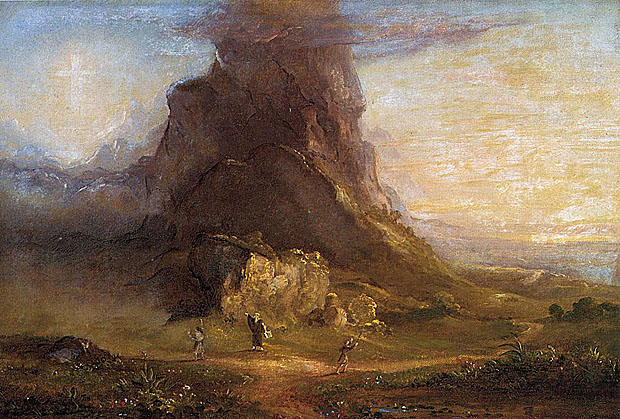

Immigrating to the United States from England at the age of eighteen, Cole was likely inspired by contemporary British art when he conceived his scene of the 'Expulsion'. He had relied upon British drawing books and prints for the rudiments of his artistic education, and his scene of Adam and Eve dwarfed by promontories of terrifying proportions recalls British painter and printmaker John Martin's illustrations for John Milton's Paradise Lost, which was popular on both sides of the Atlantic. Cole's dramatic use of light streaming through the rocky portal to Paradise is clearly reminiscent of Martin's history paintings.

In his 1835 Essay on American Scenery, Cole would describe the beauties of the American wilderness and its capacity to reveal God's creation as a metaphoric Eden. He considered European scenery to reflect the ravages of civilization, for which extensive forests had been felled, rugged mountains, had been smoothed, and impetuous rivers had been turned from their courses. In contrast, Cole believed the American wilderness to embody a state of divine grace and lamented that the signs of progress were rapidly encroaching. In his Expulsion, Cole vividly portrays both Paradise and a hostile world replete with the consequences of earthly knowledge. These opposing realms meet near the center of the canvas. The profusion of flora and fauna evokes the beauty and harmony of 'Eden'. Outside the gate to Paradise, Adam and Eve are cast into an abyss marked by blasted trees, desolate rocks, and an ominous wolf.

Hence, vain deluding joys,

The brood of folly without father bred,

How little you bestead,

Or fill the fixed mind with all your toys!

Dwell in some idle brain,

And fancies fond with gaudy shapes possess,

As thick and numberless

As the gay motes that people the sunbeams,

Or likest hovering dreams,

The fickle pensioners of Morpheus' train.

But hail thou Goddess sage and holy,

Hail divinest Melancholy,

Whose saintly visage is too bright

To hit the sense of human sight,

And therefore to our weaker view

O'erlaid with black, staid Wisdom's hue;

Black, but such as in esteem

Prince Memnon's sister might beseem,

Or that starred Ethiop queen that strove

To set her beauty's praise above

The Sea-Nymphs, and their pow'rs offended.

Yet thou art higher far descended;

Thee bright-haired Vesta long of yore

To solitary Saturn bore;

His daughter she (in Saturn's reign

Such mixture was not held a stain).

Oft in glimmering bow'rs and glades

He met her, and in secret shades

Of woody Ida's inmost grove,

While yet there was no fear of Jove.

Come, pensive Nun, devout and pure,

Sober, steadfast, and demure,

All in a robe of darkest grain,

Flowing with majestic train,

And sable stole of cypres lawn,

Over thy decent shoulders drawn:

Come, but keep thy wonted state,

With even step, and musing gait,

And looks commercing with the skies,

Thy rapt soul sitting in thine eyes:

There held in holy passion still,

Forget thyself to marble, till

With a sad leaden downward cast

Thou fix them on the earth as fast.

And join with thee calm Peace, and Quiet,

Spare Fast, that oft with gods doth diet,

And hears the Muses in a ring

Aye round about Jove's altar sing.

And add to these retired Leisure,

That in trim gardens takes his pleasure;

But first, and chiefest, with thee bring

Him that yon soars on golden wing,

Guiding the fiery-wheeled throne,

The Cherub Contemplation;

And the mute Silence hist along,

'Less Philomel will deign a song,

In her sweetest, saddest plight,

Smoothing the rugged brow of Night,

While Cynthia checks her dragon yoke,

Gently o'er th' accustomed oak;

Sweet bird, that shunn'st the noise of folly,

Most musical, most melancholy!

Thee, chauntress, oft the woods among

I woo, to hear thy even-song;

And missing thee, I walk unseen

On the dry smooth-shaven green,

To behold the wandering Moon

Riding near her highest noon,

Like one that had been led astray

Through the heav'n's wide pathless way;

And oft, as if her head she bowed,

Stooping through a fleecy cloud.

Oft on a plat of rising ground,

I hear the far-off curfew sound,

Over some wide-watered shore,

Swinging slow with sullen roar;

Or if the air will not permit,

Some still removed place will fit,

Where glowing embers through the room

Teach light to counterfeit a gloom;

Far from all resort of mirth,

Save the cricket on the hearth,

Or the bellman's drowsy charm,

To bless the doors from nightly harm:

Or let my lamp at midnight hour

Be seen in some high lonely tow'r,

Where I may oft out-watch the Bear,

With thrice-great Hermes, or unsphere

The spirit of Plato, to unfold

What worlds, or what vast regions hold

The immortal mind, that hath forsook

Her mansion in this fleshly nook:

And of those Demons that are found

In fire, air, flood, or under ground,

Whose power hath a true consent

With planet, or with element.

Sometime let gorgeous Tragedy

In sceptered pall come sweeping by,

Presenting Thebes, or Pelops' line,

Or the tale of Troy divine,

Or what (though rare) of later age

Ennobled hath the buskined stage.

But, O sad Virgin, that thy power

Might raise Musaeus from his bower,

Or bid the soul of Orpheus sing

Such notes as warbled to the string

Drew iron tears down Pluto's cheek,

And made Hell grant what Love did seek.

Or call up him that left half told

The story of Cambuscan bold,

Of Camball, and of Algarsife,

And who had Canace to wife,

That owned the virtuous ring and glass,

And of the wondrous horse of brass

On which the Tartar king did ride;

And if aught else great bards beside

In sage and solemn tunes have sung,

Of turneys and of trophies hung,

Of forests, and enchantments drear,

Where more is meant than meets the ear.

Thus, Night, oft see me in thy pale career,

Till civil-suited Morn appear,

Not tricked and frounced as she was wont

With the Attic Boy to hunt,

But kerchiefed in a comely cloud,

While rocking winds are piping loud,

Or ushered with a shower still,

When the gust hath blown his fill,

Ending on the rustling leaves

With minute drops from off the eaves.

And when the sun begins to fling

His flaring beams, me, Goddess, bring

To arched walks of twilight groves,

And shadows brown that Sylvan loves

Of pine, or monumental oak,

Where the rude axe with heaved stroke

Was never heard the Nymphs to daunt,

Or fright them from their hallowed haunt.

There in close covert by some brook,

Where no profaner eye may look,

Hide me from day's garish eye,

While the bee with honeyed thigh,

That at her flowery work doth sing,

And the waters murmuring

With such consort as they keep,

Entice the dewy-feathered Sleep;

And let some strange mysterious dream

Wave at his wings in airy stream

Of lively portraiture displayed,

Softly on my eyelids laid.

And as I wake, sweet music breathe

Above, about, or underneath,

Sent by some Spirit to mortals good,

Or the unseen Genius of the wood.

But let my due feet never fail

To walk the studious cloister's pale,

And love the high embowed roof,

With antique pillars massy proof,

And storied windows richly dight,

Casting a dim religious light:

There let the pealing organ blow

To the full voiced choir below,

In service high, and anthems clear,

As may with sweetness, through mine ear,

Dissolve me into ecstasies,

And bring all Heav'n before mine eyes.

And may at last my weary age

Find out the peaceful hermitage,

The hairy gown and mossy cell

Where I may sit and rightly spell

Of every star that heav'n doth show,

And every herb that sips the dew;

Till old experience do attain

To something like prophetic strain.

These pleasures, Melancholy, give,

And I with thee will choose to live.

_1845.jpg)

_ca_1830.jpg)

Mount Etna is one of the most active volcanoes in the world and is in an almost constant state of eruption. The fertile volcanic soils support extensive agriculture, with vineyards and orchards spread across the lower slopes of the mountain and the broad Plain of Catania to the south.

Niagara Falls are renowned both for their beauty and as a valuable source of hydroelectric power. Managing the balance between recreational, commercial, and industrial uses has been a challenge for the stewards of the falls since the 1800's.

Prometheus Bound was one of several large paintings Cole produced in the mid-1840's. He entered Prometheus Bound in a competition at Westminster Hall, London, for the selection of paintings to hang in the new British Houses of Parliament. It was not selected, however.

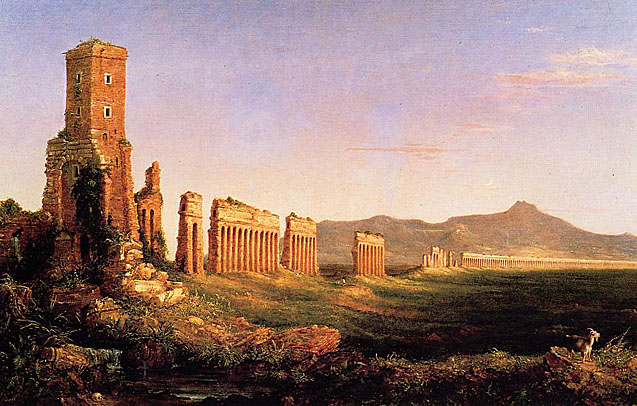

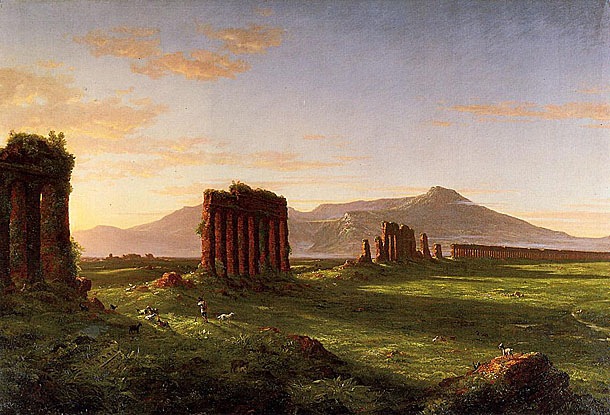

During the Ancient Roman period, it was a popular residential area, but it was abandoned during the Middle Ages due to malaria and insufficient water supplies for farming needs. The region was reclaimed in the 19th and 20th centuries for use in mixed farming and new settlements have been built. Starting with the fifties of last century, the expansion of Rome destroyed large parts of the Campagna, especially east and south of the city.

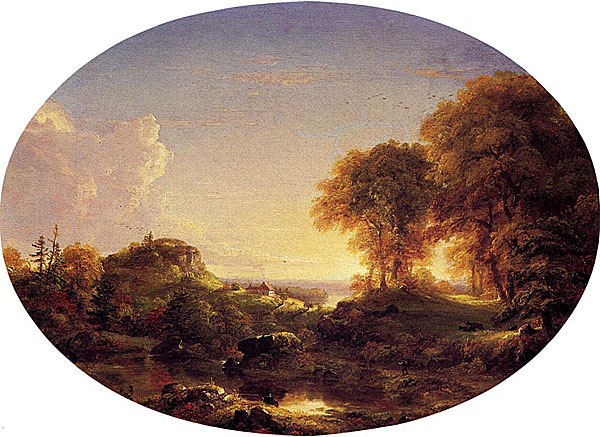

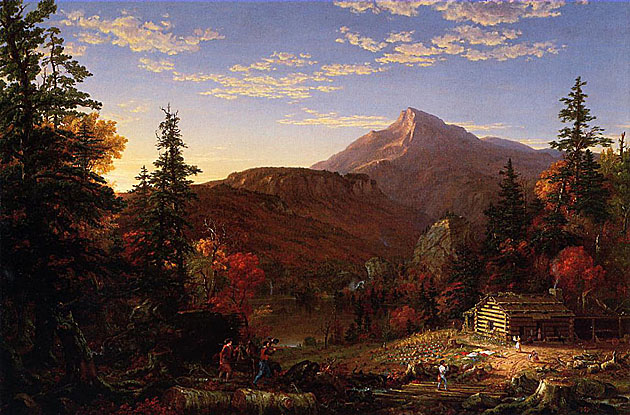

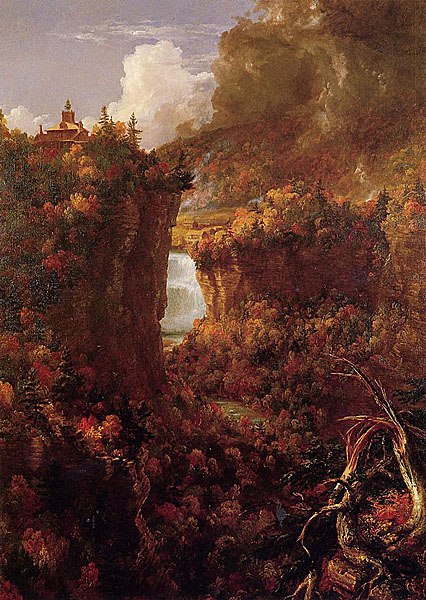

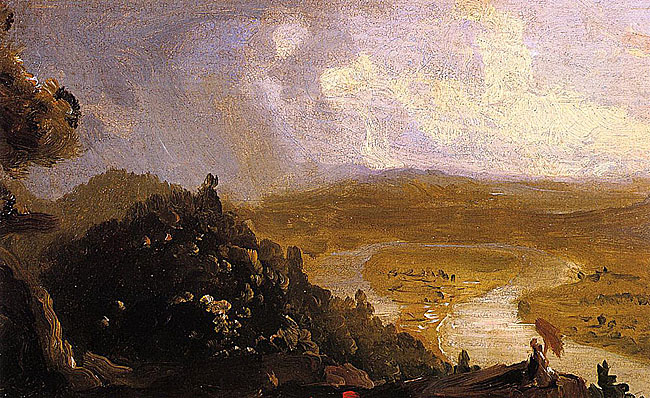

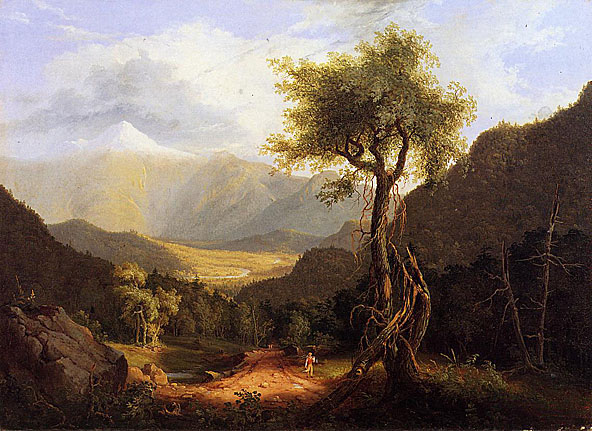

Thomas Cole first saw and sketched this view of the Adirondacks during a summer walking tour, but to dramatize the painting, he turned the scene into a blaze of autumn colors. He also elevated the vantage point to include a glimpse of the lake from which the mountain rises, thereby enhancing its height. The Native Americans hidden in the foliage prove that this is a wild, distinctly American land.

Celebrated in his day as the founder of the American landscape tradition, Cole here appears to have represented each of the four elements: earth (the massive, silhouette mountain), air (which sweeps clouds around the peak), water (the lake and the rain at right), and fire (in the blasted trunks and crimson leaves).

_1839.jpg)

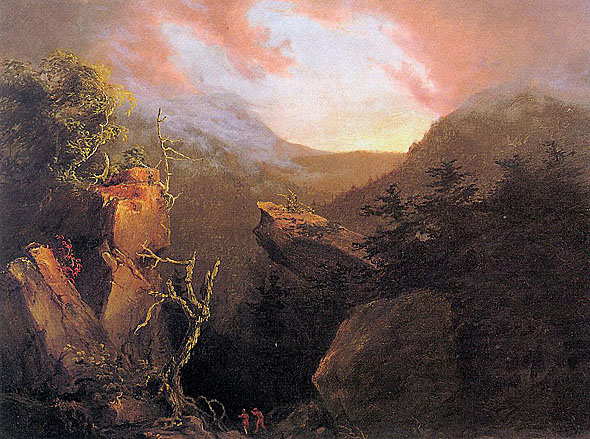

The notch is at the upper or northern end of this gorge (constituting the extreme southern end of a panhandle at the southeastern corner of the town of Carroll), where the land descends both to north and south, and ascends both to east and west. However, the steepness of the south-flowing Saco's gorge (in contrast to the leisurely descent of the northward drainage into the watershed of Crawford Brook and eventually the Ammonoosuc River) makes it natural to attach the name to the gorge.

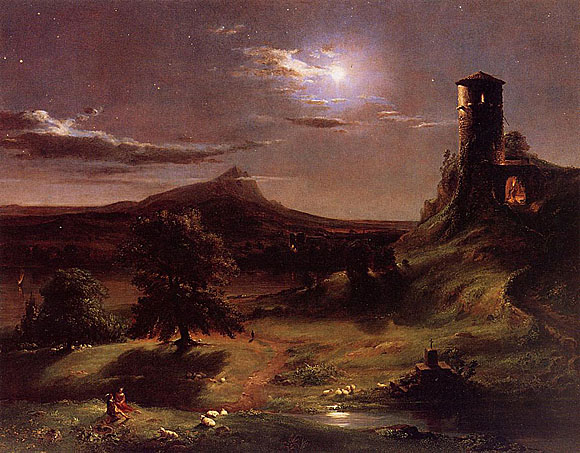

"The Past" depicts a courtly jousting contest on a summer day. From the colorful throng of spectators to the travelers on the distant road, the landscape teems with people. In contrast, the same scene in "The Present" contains only a lonely goatherd tending his flock. Now long abandoned, the castle lies in ivy-covered ruins, and water covers the fairground. Nature reclaims the land that humans overran in "The Past."

The father of the Hudson River School, Cole grew up in an industrial area in England and moved to America as a teenager. According to Sarah Burns, he feared democracy and believed in the cyclical rise and fall of empires. Perhaps these two paintings are an allegorical warning that even America cannot escape this pattern.

_1842.jpg)

These images reflect Cole's beliefs that America was a place in the world were life could begin again on a clean slate, previously uninvolved in the destructive ways of the old world. Cole stated that, "The subject of art should be pure and lofty, ... an impressive lesson must be taught, an important scene illustrated--amoral, religious or poetic effect (must) be produced on the mind."

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.