American Painter

1796 - 1872

George Catlin by William Fisk: 1849

William Fisk's portrait conveys Catlin's ideal image of his achievements. Catlin sat for this painting in London when, at the age of fifty-three, he was in the business phase of his career- staging art exhibitions and Indian performances. Nevertheless, Catlin is seen with palette and brush before a canvas- an artist at heart. Suited in buckskin, Catlin had absorbed frontier and Indian culture, even as he tried to capture those Indians fading into background shadows- a device that conveys Catlin's notions of their cultural losses. Most impressive perhaps is Catlin's intense gaze into the distance, revealing his animating vision, conviction, and persistence.

Quoted From: Campfire Stories with George Catlin

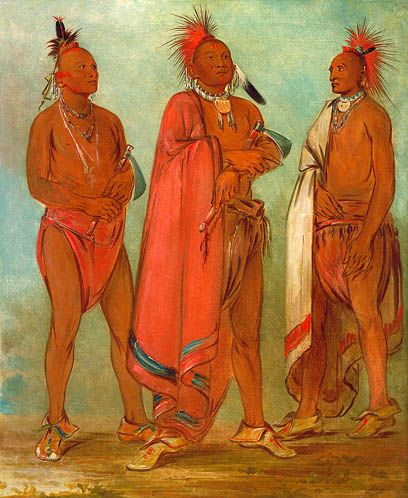

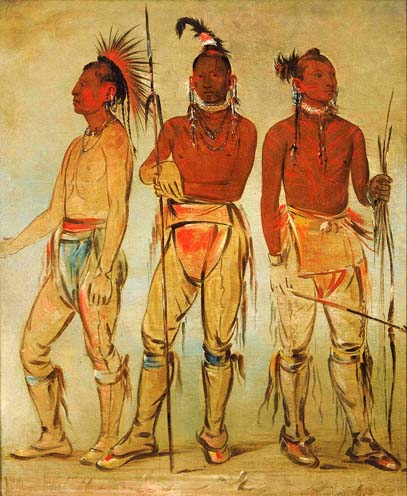

George Catlin was an American painter, author and traveler who specialized in portraits of Native Americans in the Old West.

Catlin was born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. As a child growing up in Pennsylvania, Catlin spent many hours hunting, fishing, and looking for American Indian artifacts. His fascination with Native Americans was kindled by his mother, who told him stories of the Western Frontier and how she was captured by a tribe when she was a young girl. Years later, a group of Native Americans came through Philadelphia dressed in their colorful costumes and made quite an impression on Catlin. Following a brief career as a lawyer, he produced two major collections of paintings of American Indians and published a series of books chronicling his travels among the native peoples of North, Central and South America. Claiming his interest in America's 'vanishing race' was sparked by a visiting American Indian delegation in Philadelphia, he set out to record the appearance and customs of America's native people.

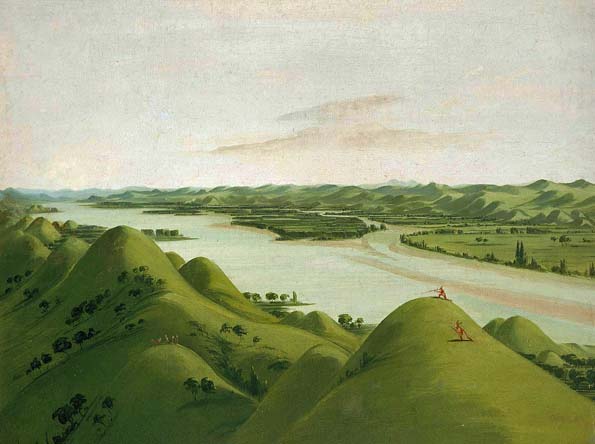

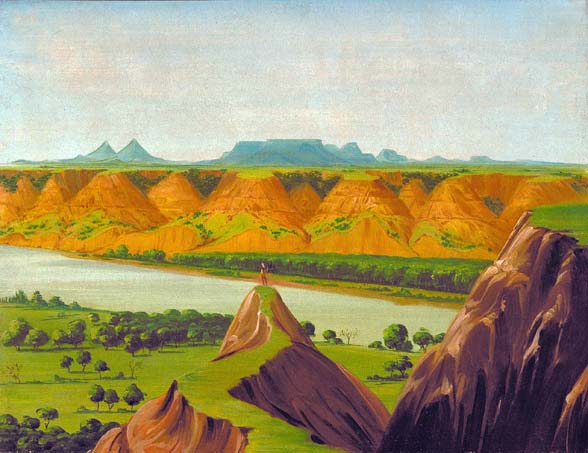

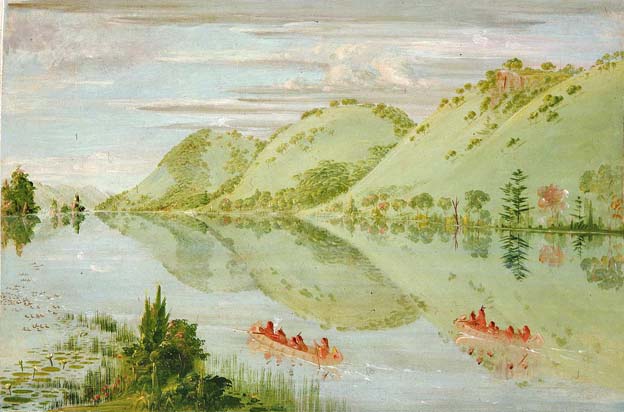

Saint Louis from the River: 1832

Catlin began his journey in 1830 when he accompanied General William Clark on a diplomatic mission up the Mississippi River into Native American territory. Saint Louis became Catlin's base of operations for five trips he took between 1830 and 1836, eventually visiting fifty tribes. Two years later he ascended the Missouri River to Fort Union, where he spent several weeks among indigenous people still relatively untouched by European civilization. He visited eighteen tribes, including the Pawnee, Omaha, and Ponca in the south and the Mandan, Hidatsa, Cheyenne, Crow, Assiniboine, and Blackfeet to the north. There, at the edge of the frontier, he produced the most vivid and penetrating portraits of his career. Later trips along the Arkansas, Red and Mississippi rivers as well as visits to Florida and the Great Lakes resulted in over 500 paintings and a substantial collection of artifacts.

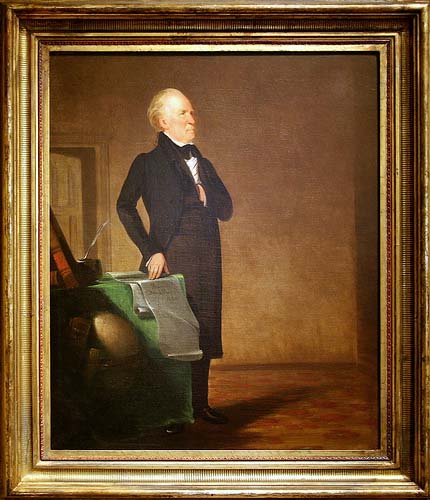

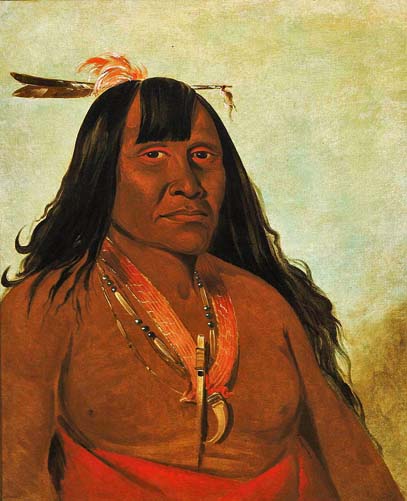

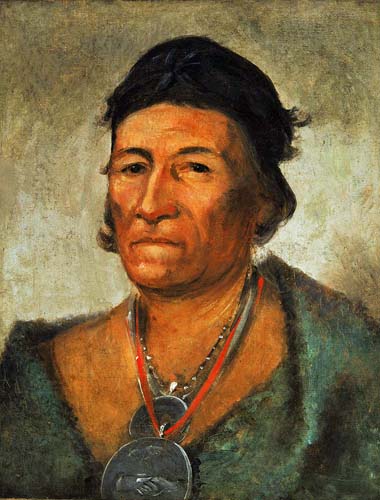

William Clark by George Catlin

When Catlin returned east in 1838, he assembled these paintings and numerous artifacts into his Indian Gallery and began delivering public lectures which drew on his personal recollections of life among the American Indians. Catlin traveled with his Indian Gallery to major cities such as Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and New York. He hung his paintings 'salon style'-side by side and one above another-to great effect. Visitors identified each painting by the number on the frame as listed in Catlin's catalogue. Soon afterwards he began a lifelong effort to sell his collection to the U.S. government. The touring Indian Gallery did not attract the paying public Catlin needed to stay financially sound, and Congress rejected his initial petition to purchase the works, so in 1839 Catlin took his collection across the Atlantic for a tour of European capitals.

Catlin the showman and entrepreneur initially attracted crowds to his Indian Gallery in London, Brussels, and Paris. The French critic Charles Baudelaire remarked on Catlin's paintings, "M. Catlin has captured the proud, free character and noble expression of these splendid fellows in a masterly way."

Catlin's dream was to sell his Indian Gallery to the U.S. government so that his life's work would be preserved intact. His continued attempts to persuade various officials in Washington, D.C. failed. He was forced to sell the original Indian Gallery, now 607 paintings, due to personal debts in 1852. Industrialist Joseph Harrison took possession of the paintings and artifacts, which he stored in a factory in Philadelphia, as security. Catlin spent the last 20 years of his life trying to re-create his collection. This second collection of paintings is known as the 'Cartoon Collection' since the works are based on the outlines he drew of the works from the 1830's.

Collection of George Catlin paintings. These are from what he called his "Cartoon Collection",

duplicates made of previous paintings that had been sold to pay debts.

In 1841 Catlin published Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians, in two volumes, with about 300 engravings. Three years later he published 25 plates, entitled Catlin's North American Indian Portfolio, and, in 1848, Eight Years' Travels and Residence in Europe. From 1852 to 1857 he traveled through South and Central America and later returned for further exploration in the Far West. The record of these later years is contained in Last Rambles among the Indians of the Rocky Mountains and the Andes (1868) and My Life among the Indians (ed. by N. G. Humphreys, 1909). In 1872, Catlin traveled to Washington, D.C. at the invitation of Joseph Henry, the first secretary of the Smithsonian. Until his death later that year in Jersey City, New Jersey, Catlin worked in a studio in the Smithsonian 'Castle'. Harrison's widow donated the original Indian Gallery-more than 500 works-to the Smithsonian in 1879.

Smithsonian Castle

The nearly complete surviving set of Catlin's first Indian Gallery painted in the 1830's is now part of the Smithsonian American Art Museum's collection. Some 700 sketches are in the American Museum of Natural History, New York City.

The accuracy of some of Catlin's observations has been questioned. He claimed to be the first white man to see the Minnesota pipestone quarries, and pipestone was named catlinite. Catlin exaggerated various features of the site, and his boastful account of his visit aroused his critics, who disputed his claim of being the first white man to investigate the quarry. Previous recorded white visitors include the Groselliers and Radisson, Father Louis Hennepin, Baron LaHonton and others. Lewis and Clark noted the pipestone quarry in their journals in 1805. Fur trader Philander Prescott had written another account of the area in 1831.

Many historians and descendants believe George Catlin had two families; his acknowledged family on the east coast of the United States, but also a family farther west, started with a Native American woman.

Two other artists of the Old West related to George Catlin by family bloodlines are Frederic Remington and Earl W. Bascom.

Quoted From: George Catlin - Wikipedia

Additional Sources:

Art Renewal Center: Museum Artist Information for George Catlin

Museum Syndicate: Art by George Catlin

Selected Works by George Catlin

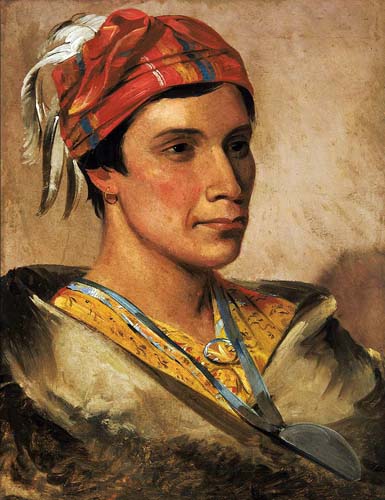

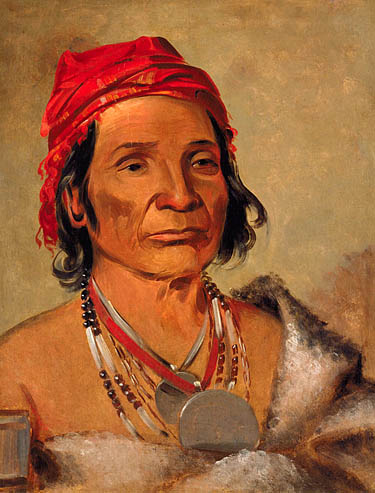

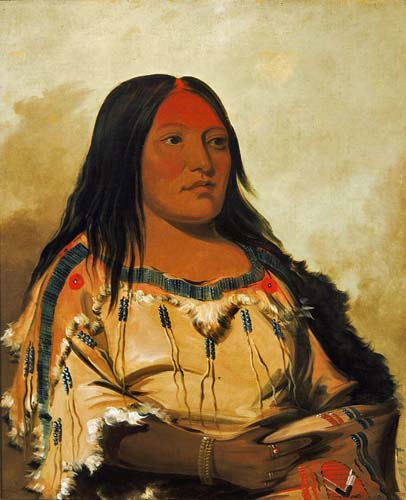

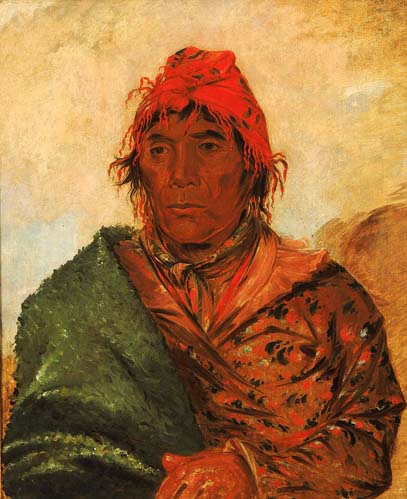

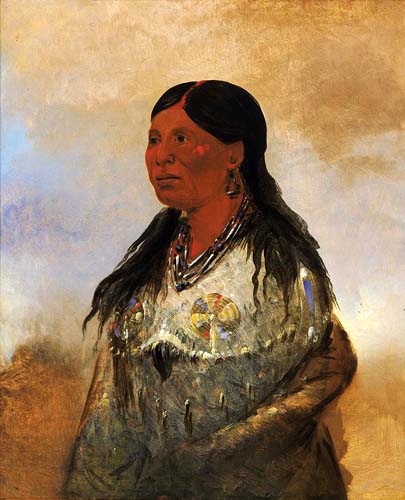

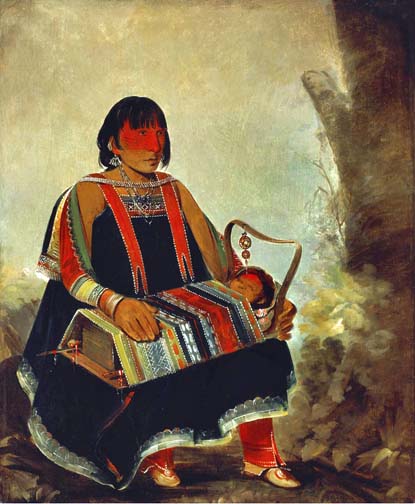

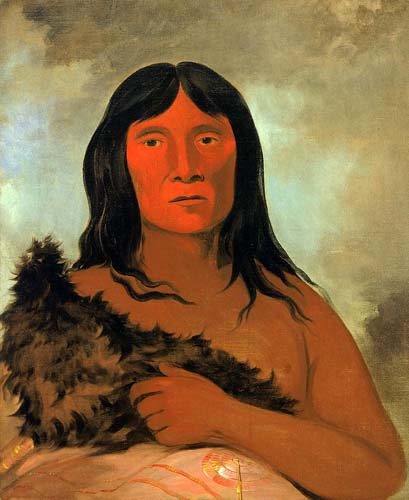

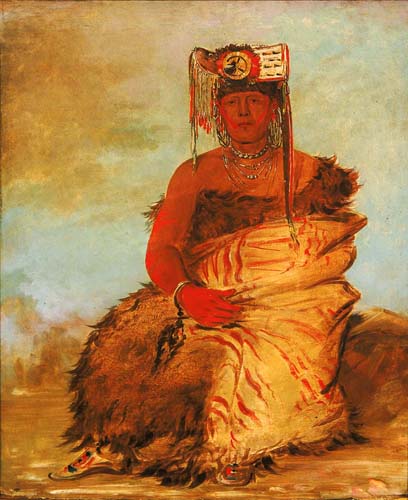

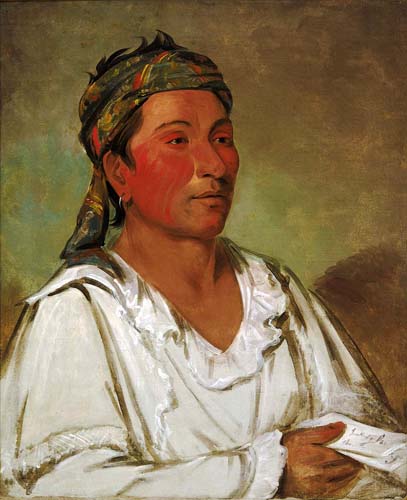

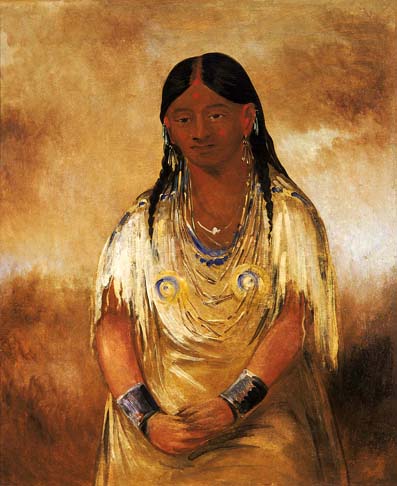

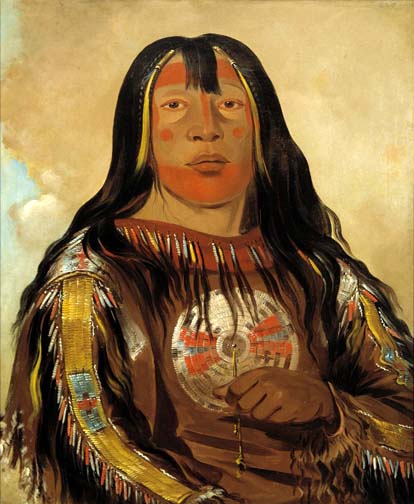

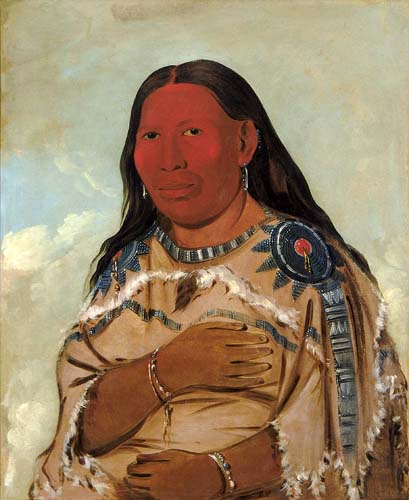

A Choctaw Woman: 1834

A Seminole Woman: 1838

George Catlin arrived at Fort Moultrie, in Charleston, South Carolina, on January 17, 1838. He painted more than ten portraits of Seminole and Yuchi Indians, including this Seminole woman, in the short time he spent at the fort. (Truettner, The Natural Man Observed, 1979)

Quoted From: Luce Foundation Center for American Art

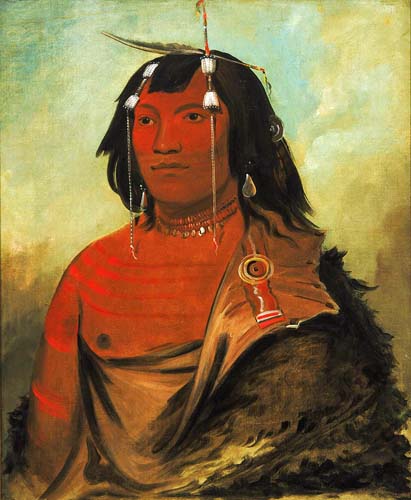

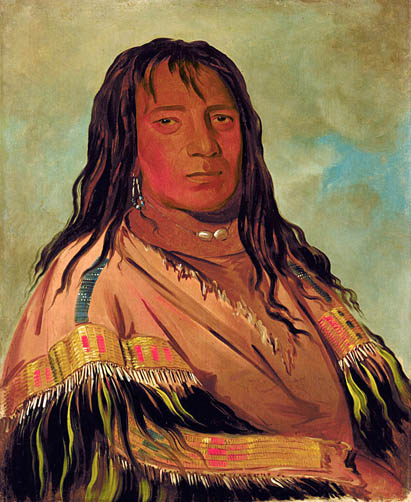

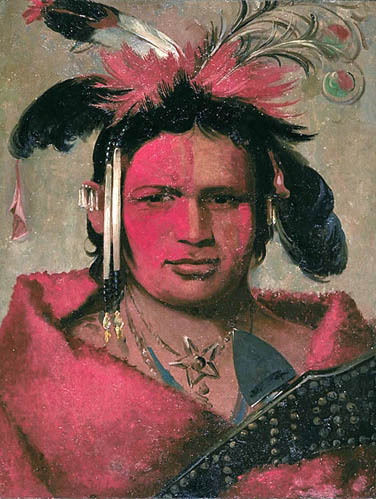

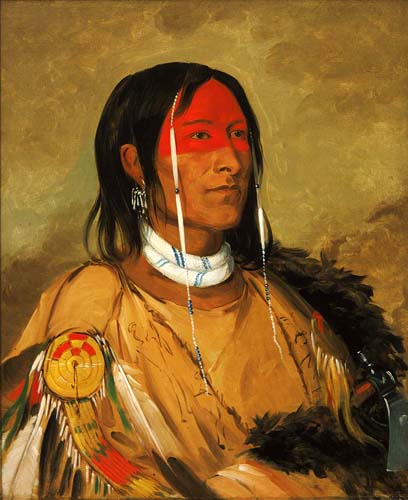

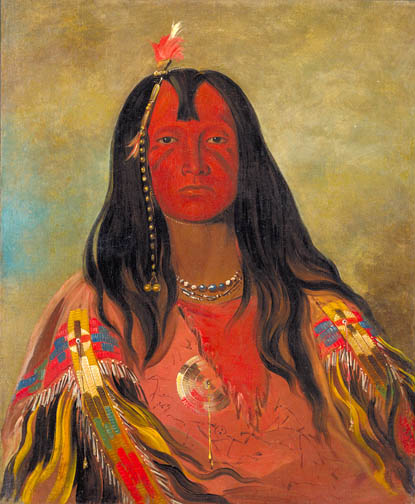

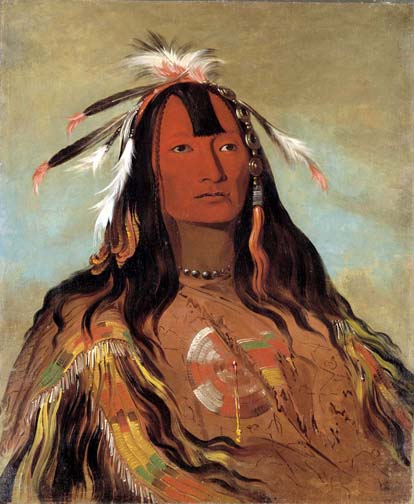

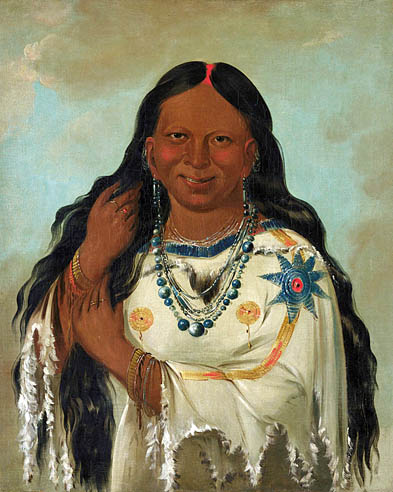

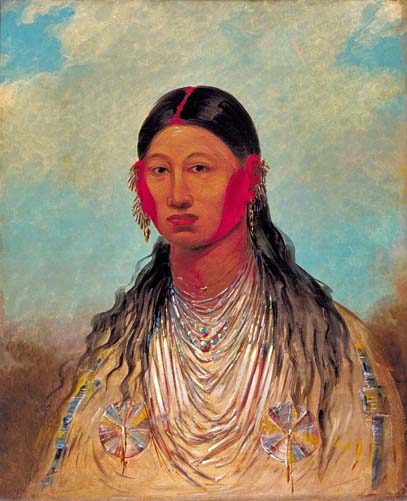

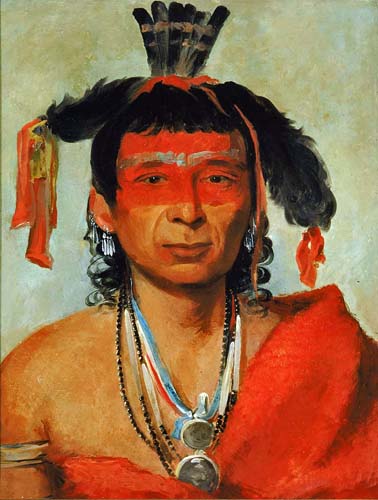

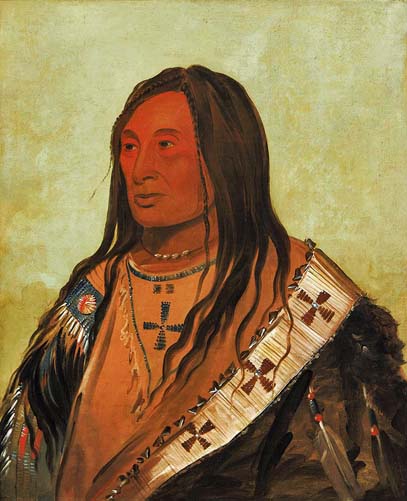

Ah'-kay-ee-pix-en

Woman Who Strikes Many: 1832

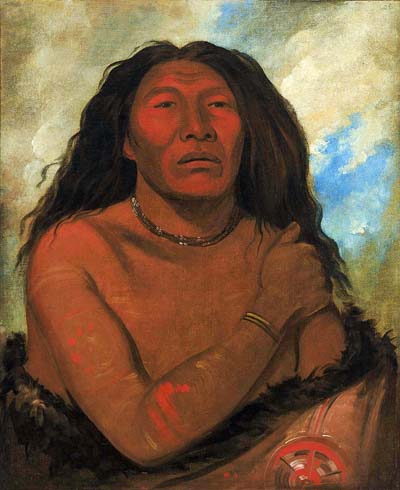

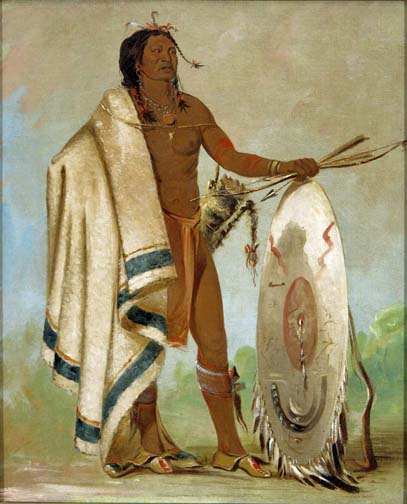

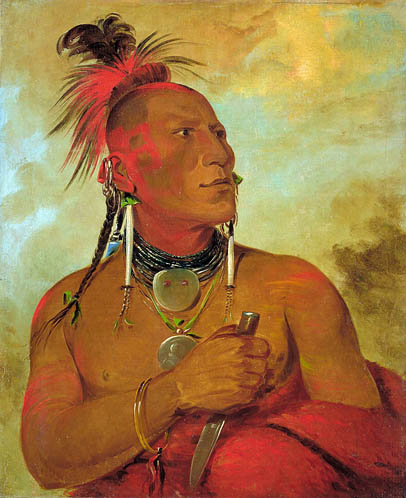

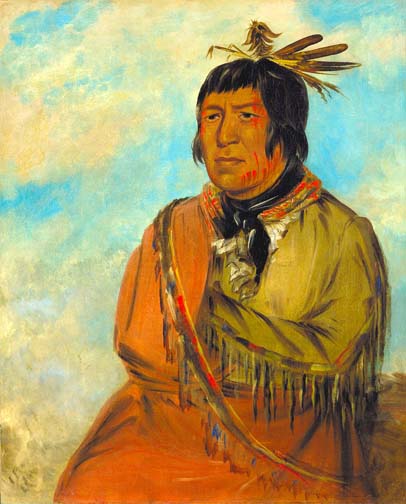

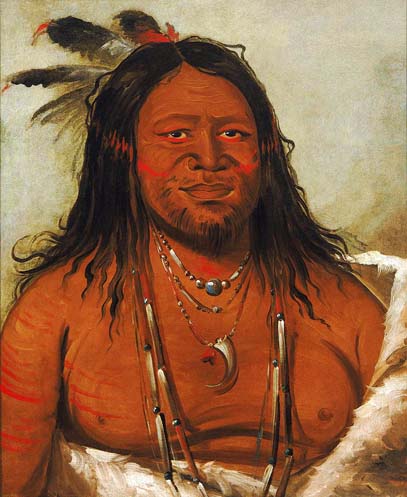

A-h'sha-la-coots-ah

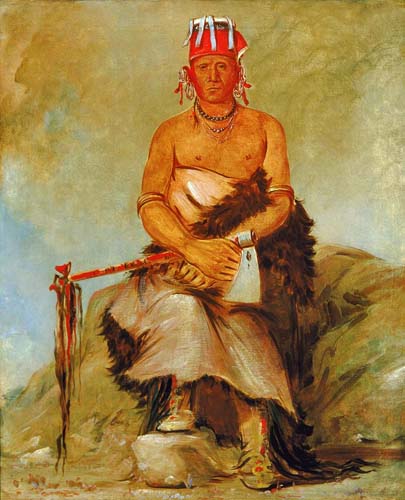

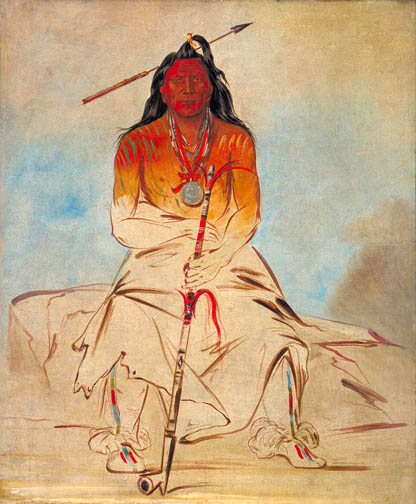

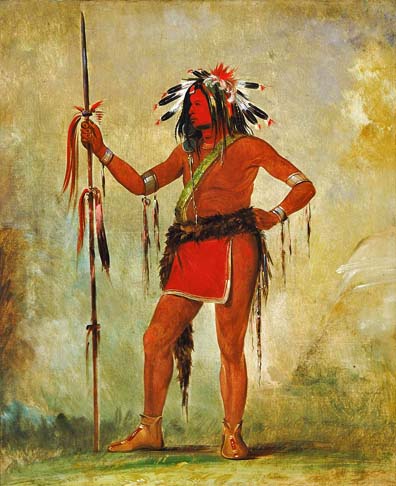

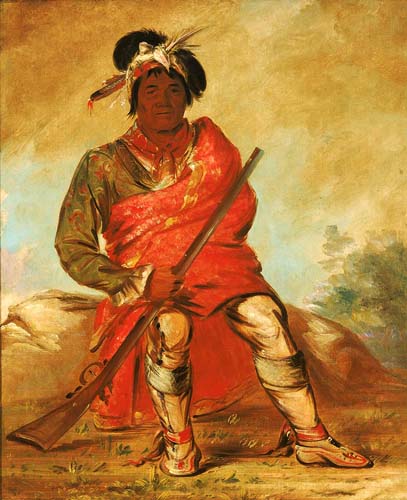

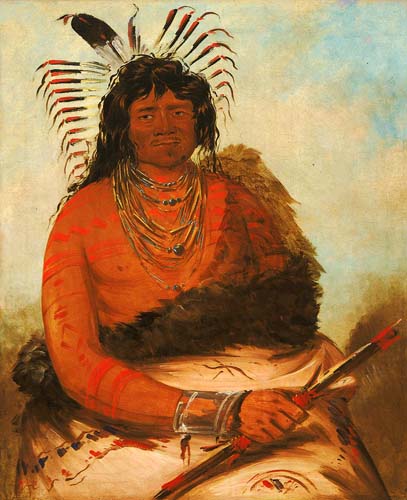

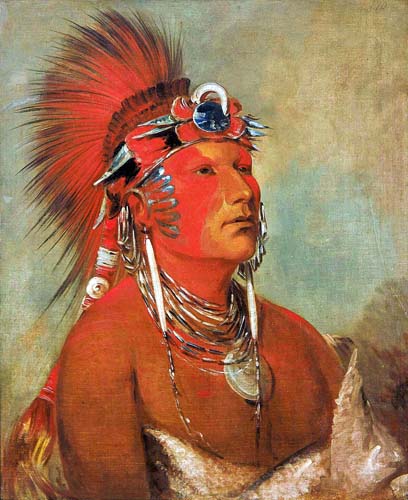

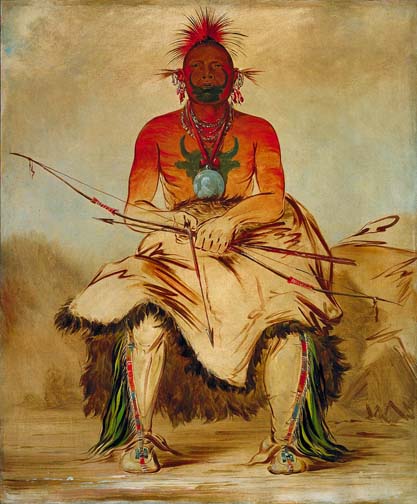

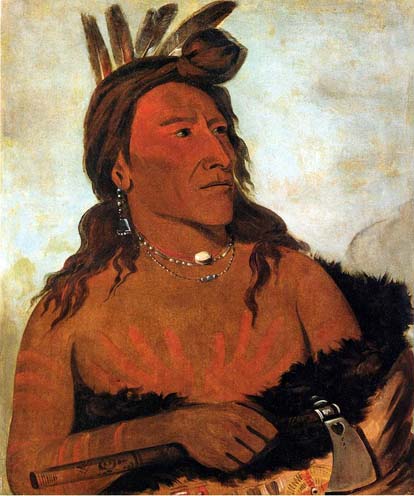

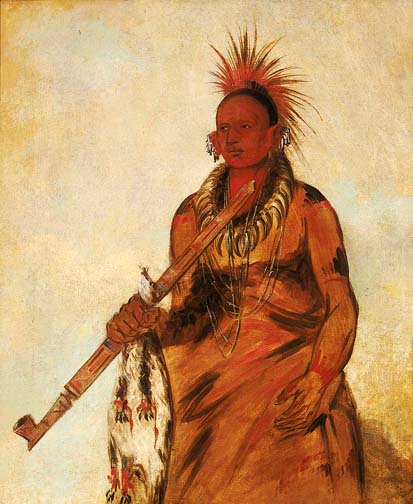

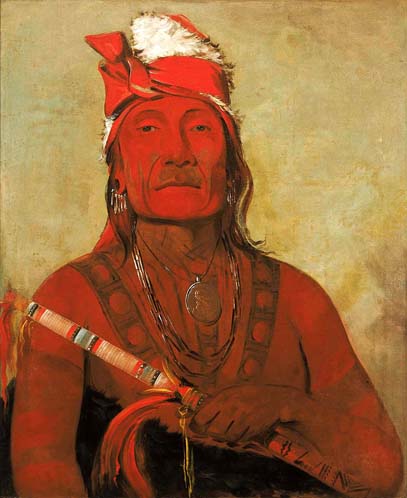

Chief of the Republican Pawnee: 1832

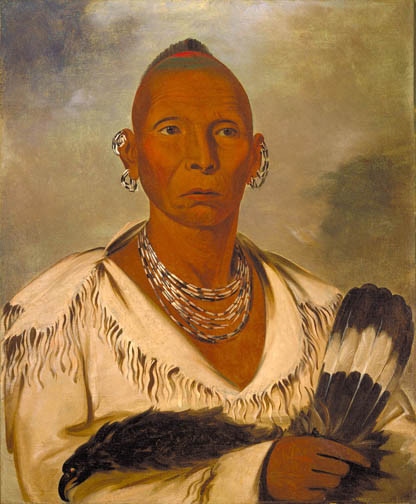

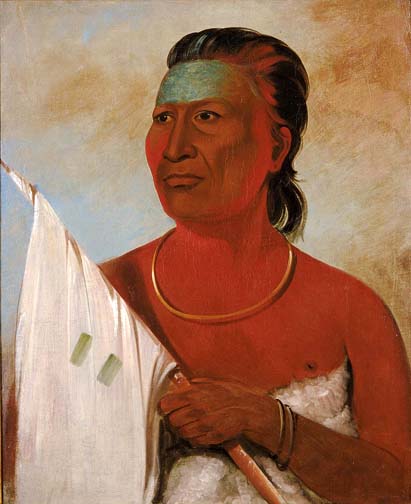

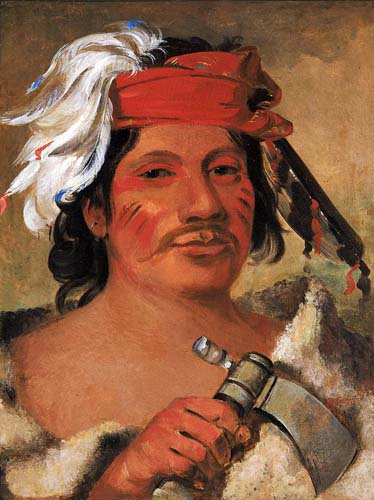

Ah'-sho-cole,

Rotten Foot, a Noted Warrior: 1834

A-h'tee-wat-o-mee-a Woman: 1830

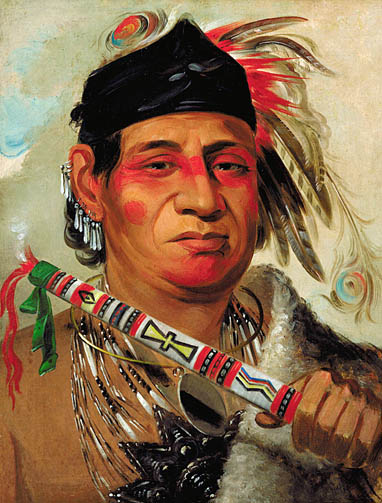

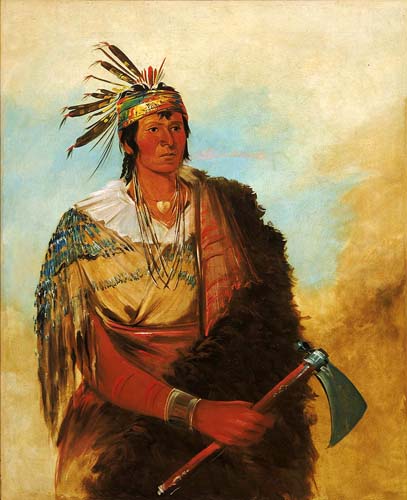

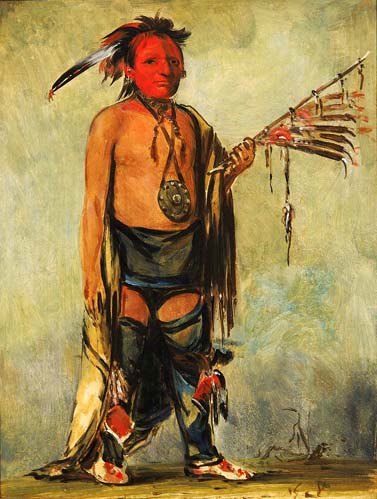

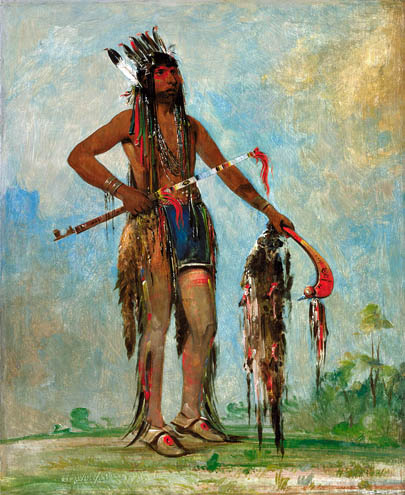

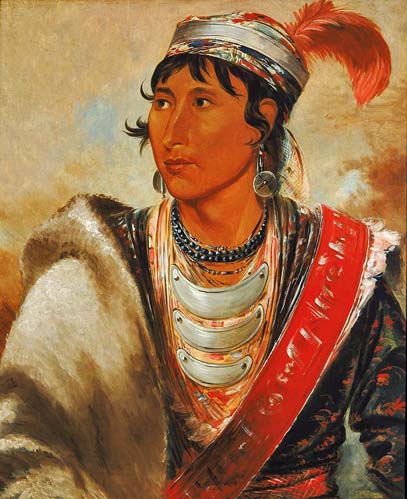

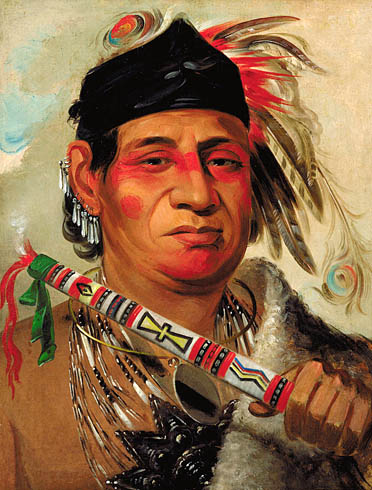

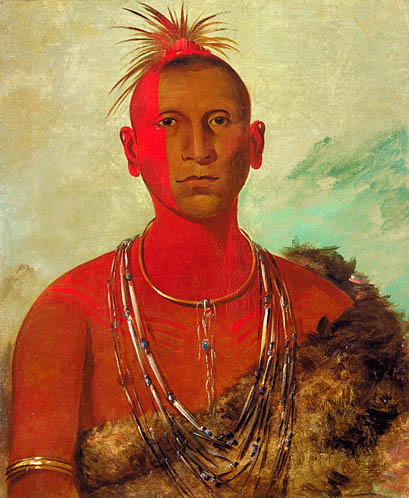

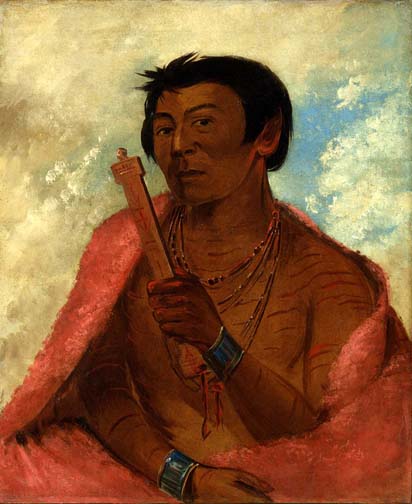

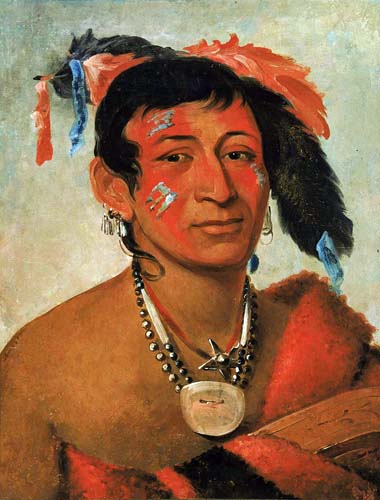

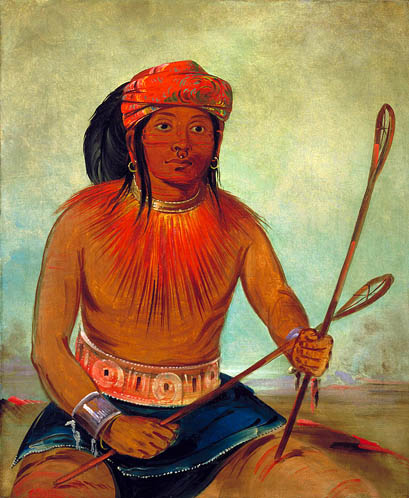

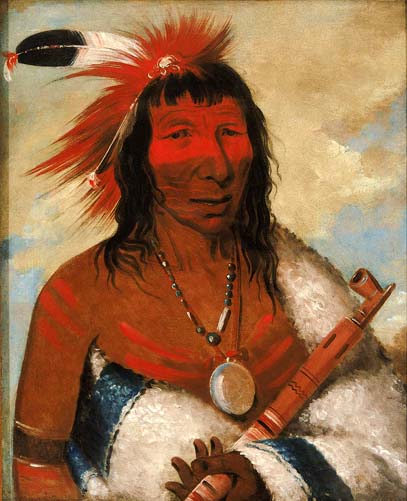

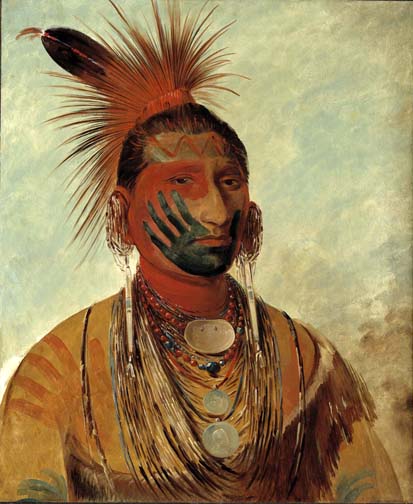

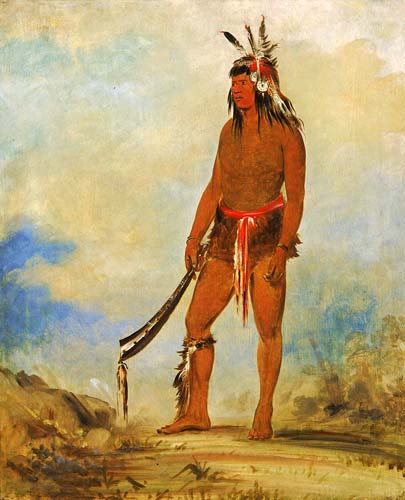

Ah-móu-a, The Whale,

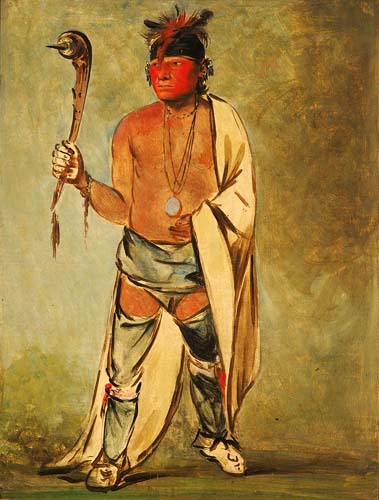

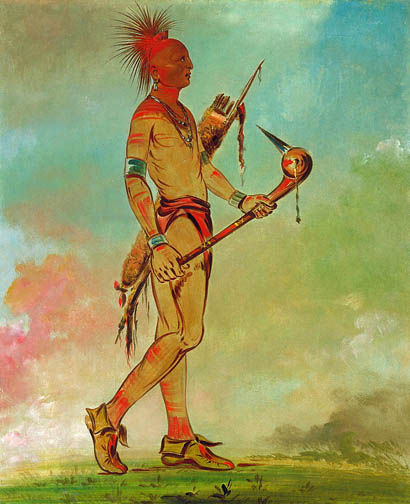

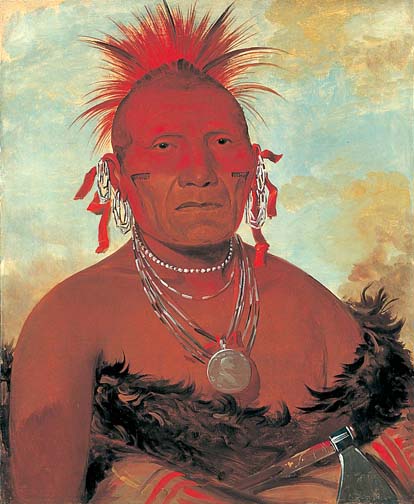

One of Kee-o-kuk's Principal Braves: 1845

Catlin describes the subject as "holding a handsome war-club in his hand" (1848 catalogue, p. 9).

Painted at the Sauk and Fox village in 1835. The Whale's display of costume accessories and weapons rivals that of Keokuk. The subject, holding the same war club, appears again in cartoon 13, with his wife.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Another Biography of George Catlin from About.com

George Catlin Painted American Indians in the Early 1800's

Artist and Writer Documented Indian Life Across North America

By Robert McNamara

Niagara Falls: 1827

The American artist George Catlin became fascinated with Indians in the early 1800's and traveled extensively throughout North America so he could document them on canvas. In his paintings and writings Catlin portrayed Indian life in great detail.

"Catlin's Indian Gallery," an exhibit which opened in New York City in 1837, was an early opportunity for people living in an eastern city to appreciate the lives of the Indians still living on the western frontier. It was, in a sense, the first "western."

Catlin is also credited with first proposing the idea of National Parks. Catlin's proposal came decades before the US government would create the first National Park.

Early Life of George Catlin

George Catlin was born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania on July 26, 1796. His mother and grandmother had been held hostage during an Indian uprising in Pennsylvania known as the Wyoming Valley Massacre some 20 years earlier, and Catlin would have heard many stories about Indians as a child. He spent much of his childhood wandering in the woods and searching for Indian artifacts.

As a young man Catlin trained to be a lawyer, and he briefly practiced law in Wilkes-Barre. But he developed a passion for painting. By 1821, at the age of 25, Catlin was living in Philadelphia and trying to pursue a career as a portrait painter.

While in Philadelphia Catlin enjoyed visiting the museum administered by Charles Willson Peale, which contained numerous items related to Indians and also to the expedition of Lewis and Clark. When a delegation of western Indians visited Philadelphia, Catlin painted them and decided to learn all he could of their history.

In the late 1820's Catlin painted portraits, including one of New York Governor DeWitt Clinton. At one point Clinton gave him a commission to create lithographs of scenes from the newly opened Erie Canal, for a commemorative booklet.

Dewitt Clinton

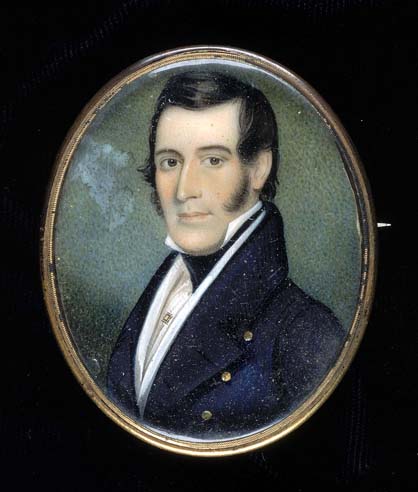

Captain Henry P. Fleischman: 1825

Mr. Fred H. Robertson: 1824

Mrs. Putnam Catlin: 1825

Portrait of a Gentleman: 1830

Portrait of a Woman: 1825

Portrait of Mary Catlin: 1827

In 1828 Catlin married Clara Gregory, who was from a prosperous family of merchants in Albany, New York. Despite his happy marriage, Catlin desired to venture off and see the west.

_1828.jpg)

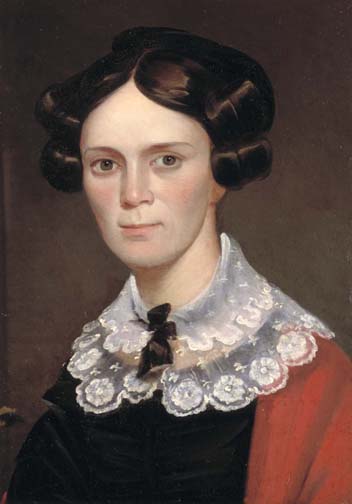

Mrs George Catlin

(Clara Bartlett Gregory): 1828

In the first of many daring decisions, George Catlin left a law career and moved to Philadelphia in 1821 to earn his living as an artist. There he became an accomplished miniature painter. He moved again in 1827 to New York City, where he began painting portraits and met the woman who would become his wife. This depiction of Clara Gregory Catlin was executed the same year they were married, 1828.

Quoted From: Campfire Stories with George Catlin

George Catlin Travels In the Western United States

In 1830, Catlin realized his ambition to visit the west, and arrived in Saint Louis, which was then the edge of the American frontier. He met William Clark, who, a quarter-century earlier, had led the famed Lewis and Clark Expedition to the Pacific Ocean and back.

Clark held an official position as the superintendent of Indian affairs. He was impressed by Catlin's desire to document Indian life, and provided him with passes so he could visit Indian reservations.

The aging explorer shared with Catlin an extremely valuable piece of knowledge, Clark's map of the west. It was, at the time, the most detailed map of North America west of the Mississippi.

Throughout the 1830's Catlin traveled extensively, often living among the Indians. In 1832 he began to paint the Sioux, who were at first highly suspicious of his ability to record detailed images on paper. However, one of the chiefs declared that Catlin's 'medicine' was good, and he was allowed to paint the tribe extensively.

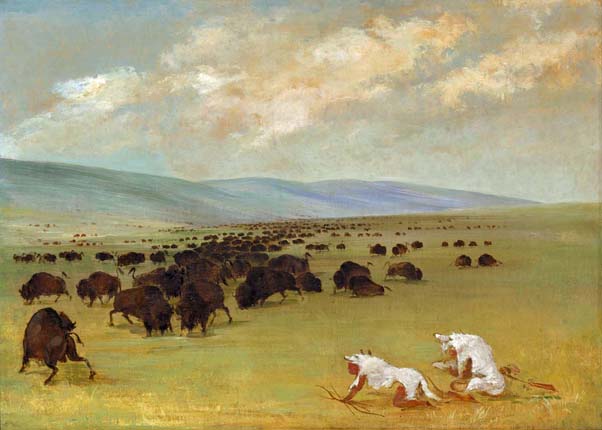

Catlin often painted portraits of individual Indians, but he also depicted daily life, recording scenes of rituals and even sports. In one painting Catlin depicts himself and an Indian guide wearing the pelts of wolves while crawling in the prairie grass to closely observe a herd of buffalo.

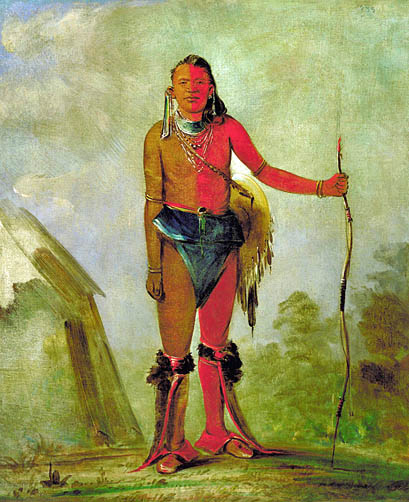

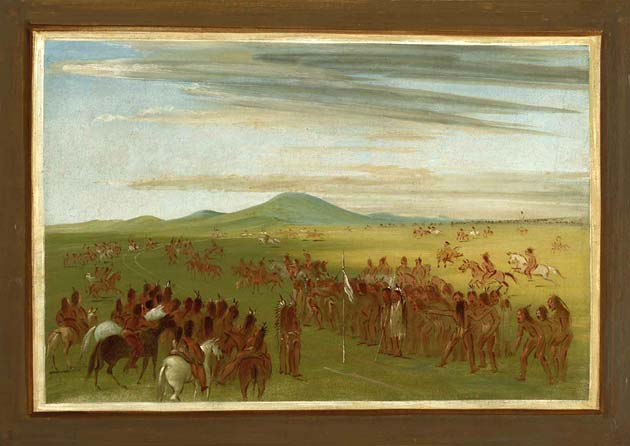

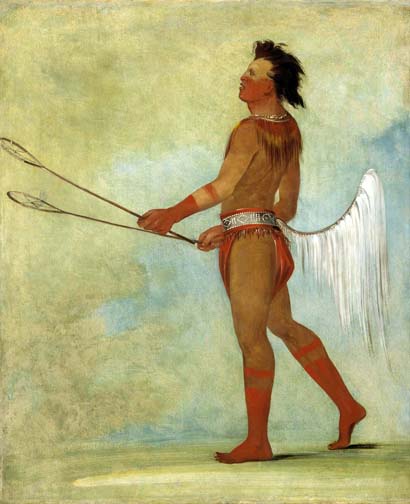

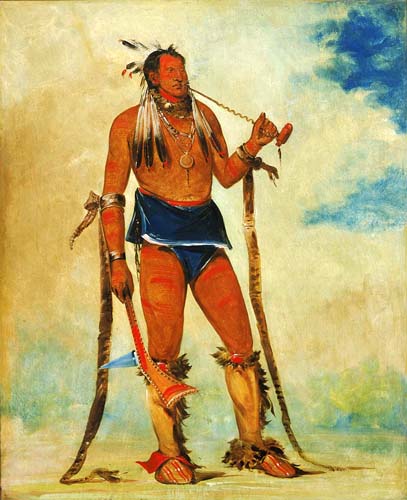

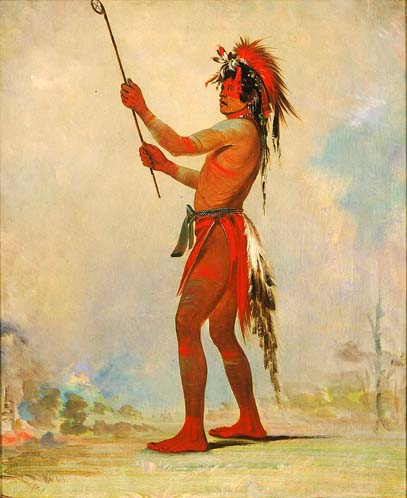

An-nó-je-nahge,

He Who Stands on Both Sides, a Distinguished Ball Player: 1835

"The two most distinguished ballplayers in the Sioux tribe. (acc. nos. 1985.66.74 and 1985.66.75) … Both of these young men stood to me for their portraits, in the dresses precisely in which they are painted; with their ball-sticks in their hands, and in the attitudes of the play. We have had several very spirited plays here within the past few days; and each of these young men came from the ball-play ground to my painting-room, in the dress in which they had just struggled in the play" (Letters and Notes, vol. 2, p. 134, pls. 235, 236).

Painted at Fort Snelling in 1835. The structure and movement of the two figures represent some improvement over the Osage series (see White Hair, the Younger, a Band Chief, Handsome Bird, and Little Chief.

Both subjects appear again in plate 21 of Catlin's North American Indian Portfolio, first published in 1844, and in carton 82 (National Gallery of Art, 2085). The cartoon is based on a watercolor (pl. 50) in the Gilcrease Souvenir album.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

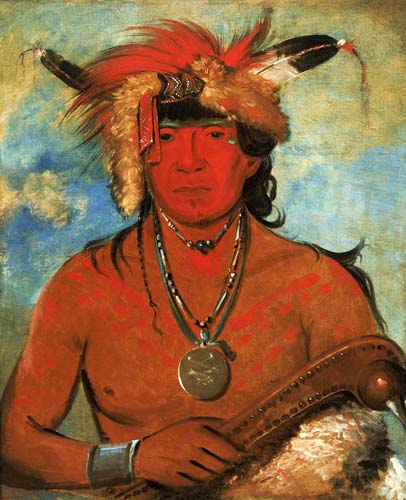

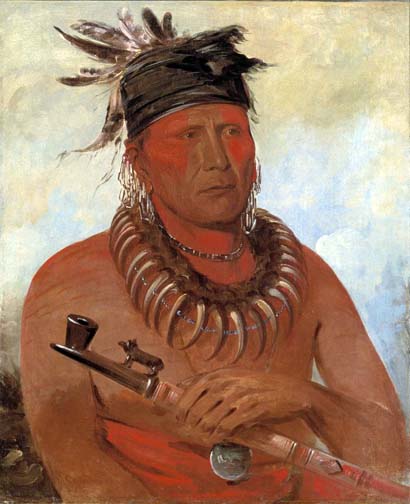

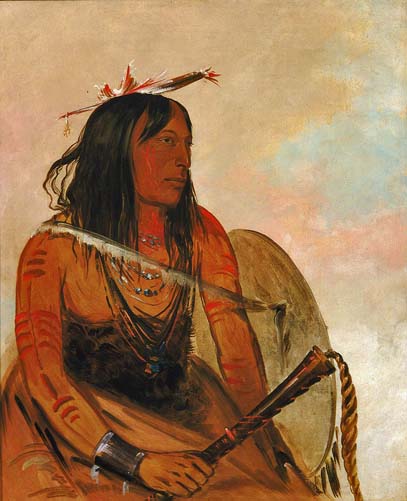

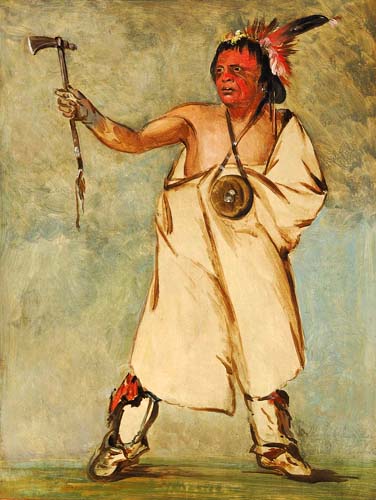

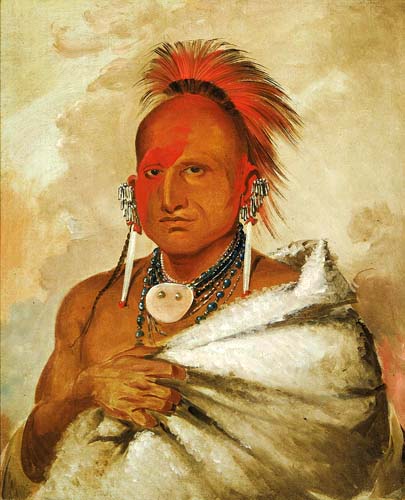

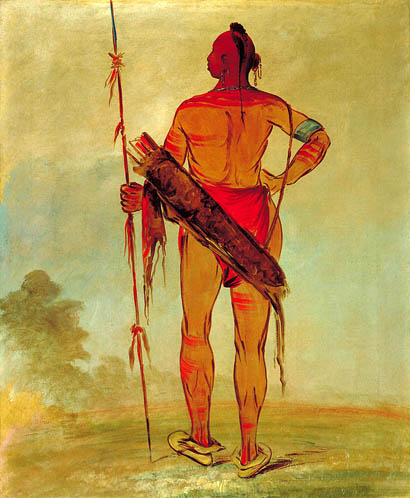

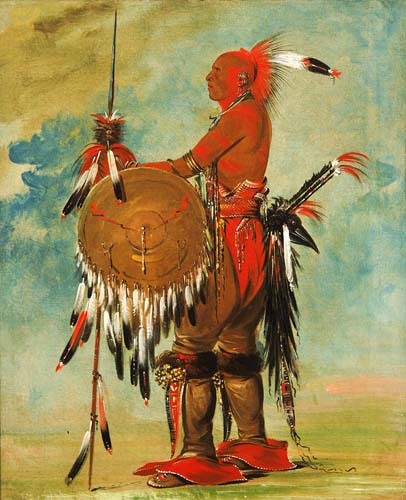

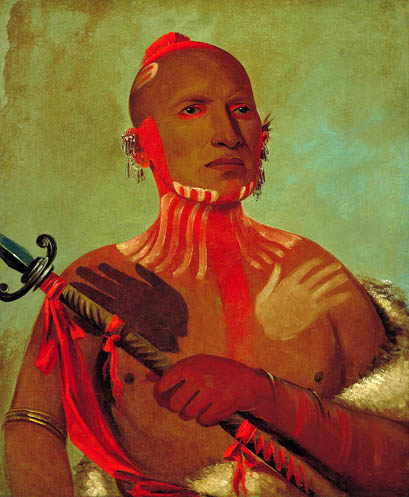

Ah-shaw-wah-rooks-te,

Medicine Horse, a Grand Pawnee Brave: 1832

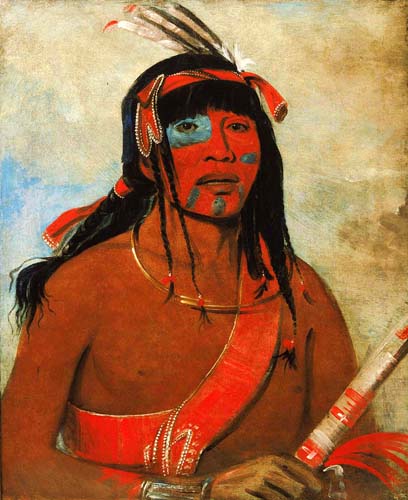

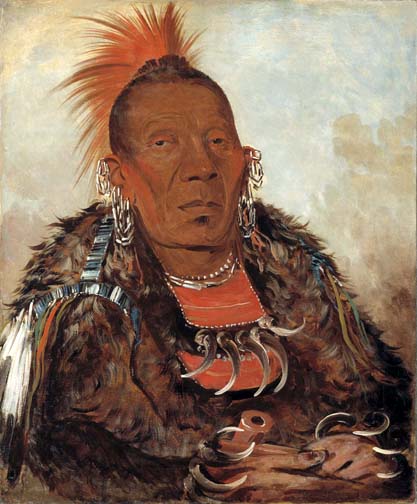

Ah-tón-we-tuck,

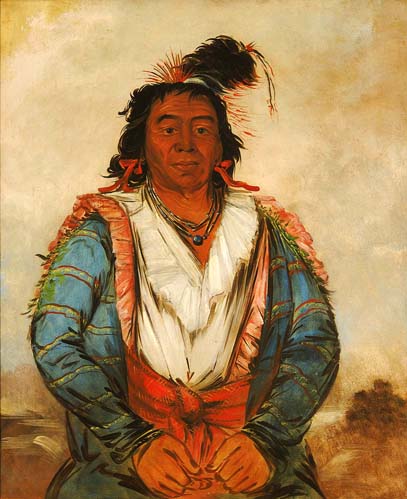

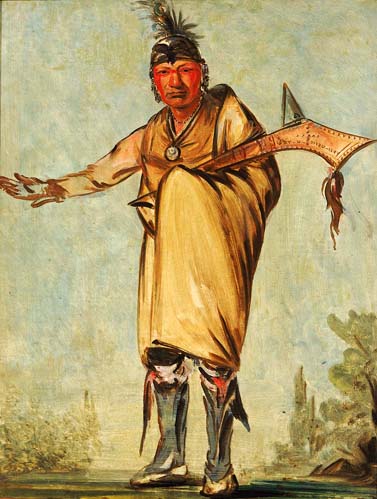

Cock Turkey-Repeating His Prayer: 1830

Described by Catlin as "another Kickapoo of some distinction, and a disciple of the Prophet; in the attitude of prayer also, which he is reading off from characters cut upon a stick that he holds in his hands" (Letters and Notes, vol. 2).

Probably painted at Fort Leavenworth in 1830. The portrait of Cock Turkey is either one of Catlin's best efforts at the fort that year, or it was mostly finished at a later date. The motif of the prayer stick, repeated in other Potawatomi and Kickapoo portraits, would probably indicate a date of 1830, but the hands are so skillfully articulated that one wonders why those of the Prophet came off so badly. The head is modeled with broad, flowing strokes that gracefully define the skull structure and facial features, a technique not often used by the artist before 1832, and the decorative tufts on the dress of the subject have been painted with astonishing speed and facility.

Cock Turkey's costume in the Gilcrease watercolor lacks many of the details that enliven the Smithsonian portrait. He appears again, full length, in cartoon 72.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Ah-yaw-ne-tak-oar-ron,

a Warrior: 1831

Aih-no-wa,

The Fire, a Fox Medicine Man: 1835

An Osage Indian Lancing a Buffalo: 1847

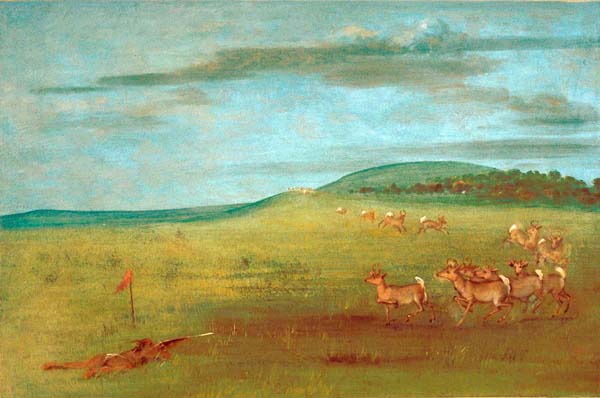

Antelope Shooting,

Decoyed Up: 1832

Catlin described antelope as another variety of game already wary of a possible hunter. "The antelope of this country, I believe to be different from all other known varieties, and forms one of the most pleasing, living ornaments to this western world. They are seen in some places in great numbers sporting and playing about the hills and dales; and often, in flocks of fifty or a hundred, will follow the boat of the descending voyageur, or the travelling caravan, for hours together; keeping off at a safe distance, on the right or left, galloping up and down the hills, snuffing their noses and stamping their feet; as if they were endeavoring to remind the traveler of the wicked trespass he was making on their own hallowed ground" (Letters and Notes, Letter No. 10).

Quoted From: Campfire Stories with George Catlin

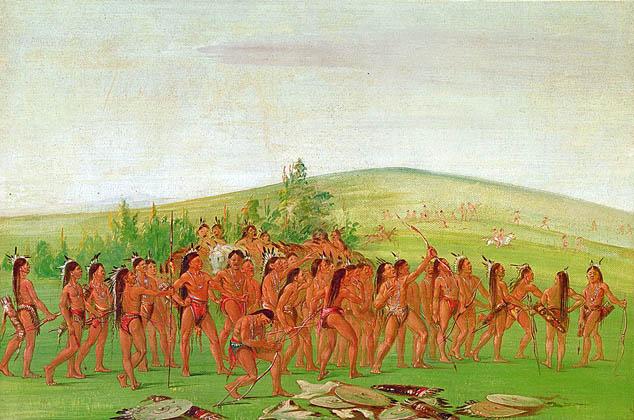

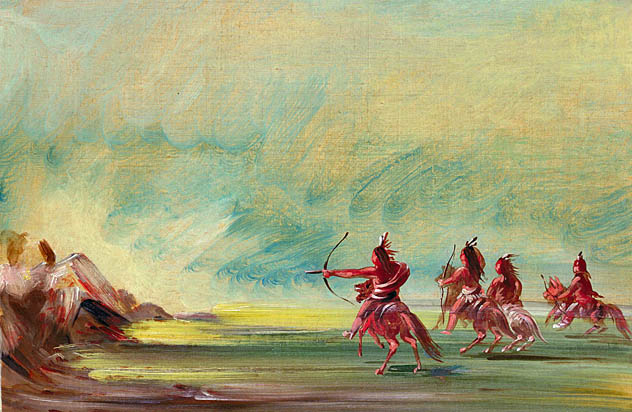

Archery of the Mandan: 1836

"I have seen a fair exhibition of their archery this day, in a favorite amusement which they call the 'game of the arrow,' where the young men who are the most distinguished in this exercise, assemble on the prairie at a little distance from the village, and having paid, each one, his 'entrance-fee,' such as a shield, a robe, a pipe, or other article, step forward in turn, shooting their arrows into the air, endeavoring to see who can get the greatest number flying in the air at one time, thrown from the same bow" (Letters and Notes, vol. 1).

Probably sketched in 1832 at the Mandan village, but the style of the painting is closer to the dance scenes. Catlin has turned the game into a major anatomy demonstration. The frieze of contestants, all looking like young Apollos, is the most carefully arranged and balanced group to be found in any of the artist's paintings.

The scene is repeated in plate 24 of Catlin's North American Indian Portfolio, first published in 1844, and in cartoon 174, with a less formal arrangement of figures.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

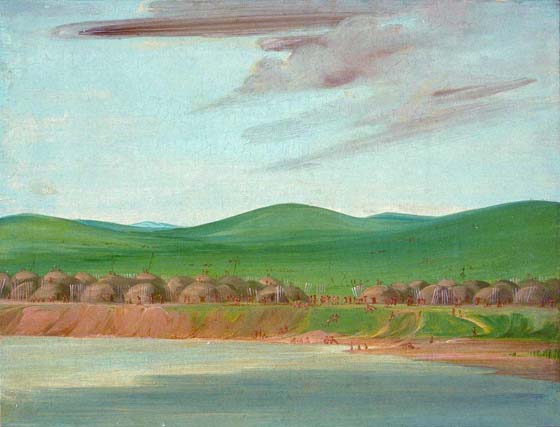

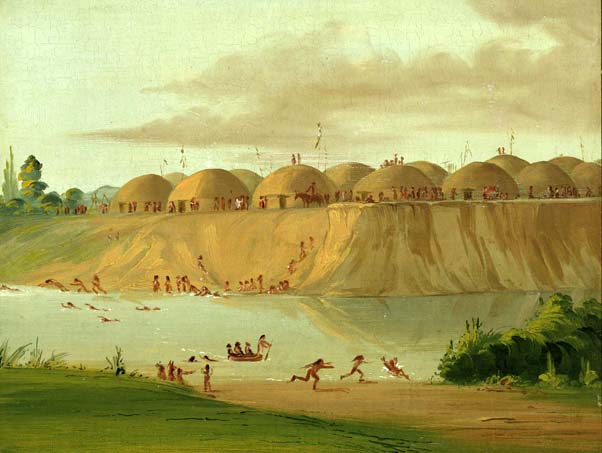

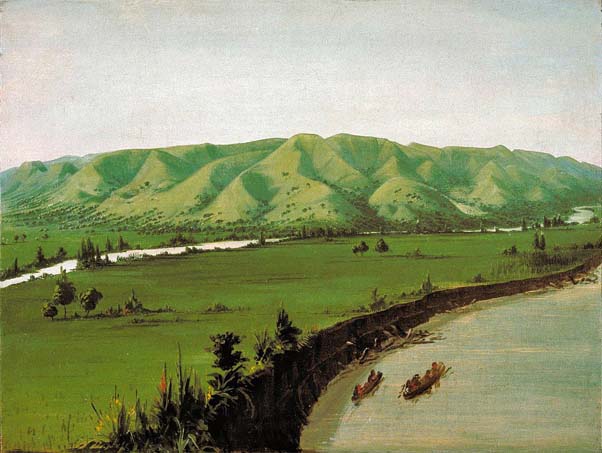

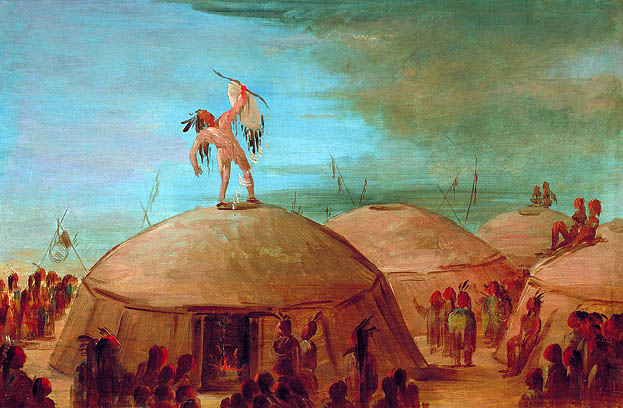

Arikara Village of Earth, Covered Lodges,

1600 Miles above Saint Louis: 1832

"Plate 80 gives a view of the Ricaree village, which is beautifully situated on the west bank of the river, 200 miles below the Mandans; and built very much in the same manner; being constituted of 150 earth-covered lodges, which are in part surrounded by an imperfect and open barrier of pickets set firmly in the ground, and ten or twelve feet in height.

"This village is built upon an open prairie, and the gracefully undulating hills that rise in the distance behind it are everywhere covered with a verdant green turf, without a tree or a bush anywhere to be seen. This view was taken from the deck of the steamer when I was on my way up the river" (Letters and Notes, vol. 1, p. 204, pl. 80).

Painted in 1832 on Catlin's Missouri River voyage.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

George Catlin Exhibits "Catlin's Indian Gallery"

In 1837 Catlin opened a gallery of his paintings in New York City, billing it as "Catlin's Indian Gallery." It could be considered the first "Wild West" show, as it revealed the exotic life of the Indians of the west to city dwellers.

Catlin wanted his exhibit to be taken seriously as historic documentation of Indian life, and he endeavored to sell his collected paintings to the US Congress. One of his great hopes was that his paintings would be the centerpiece of a national museum devoted to Indian life.

The Congress was not interested in purchasing Catlin's paintings, and when he exhibited them in other eastern cities they were not as popular as they had been in New York. Frustrated, Catlin left for England, where he found success showing his paintings in London.

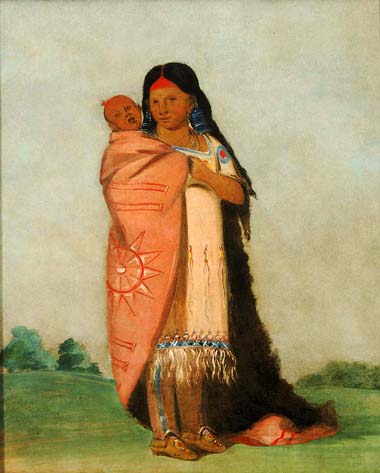

Assiniboin Woman and Child: 1832

"The women of this tribe are often comely, and sometimes pretty; in plate 34, will be seen a fair illustration of the dresses of the women and children, which are usually made of the skins of the mountain-goat, and ornamented with porcupine's quills and rows of elk's teeth" (Letters and Notes, vol. 1, p. 57, pl. 34).

Painted at Fort Union in 1832. Although number 159 is a notable exception, Catlin's small children often look like shrunken adults. The Field Museum and Smithsonian portraits are alike, except for the seated child and skin lodges in the background of the latter. That same background is repeated in plate 34 of Letters and Notes.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

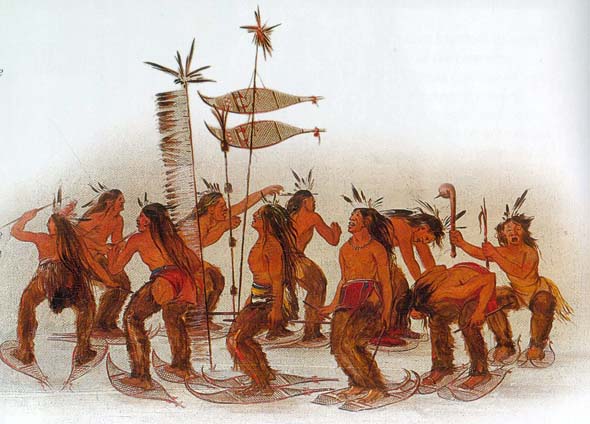

Assiniboine Indians Pursuing Buffalo on Snowshoes: 1847

Painted in Paris 1846-1848. Catlin must have produced over 100 pictures between 1846 and early 1848. Those intended for Louis Philippe were finished with great care (see no. 449), but others are little more than hasty sketches he painted to round out his collection for European audiences. Even at high speed, however, Catlin had a surprisingly delicate and sure touch, giving to his figures the animated presence of actors on a miniature stage. The setting is not the Great Plains or the Upper Missouri, but a land of fantastic foliage and bright pastel tones shaped by the artist's beguiling and fanciful memory.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Auh-ka-nah-paw-wah,

Earth Standing, an Old and Valiant Warrior: 1831

Au-nah-kwet-to-hau-pay-o,

One Sitting in the Clouds, a Boy: 1831

Au-nim-muck-kwa-um,

Tempest Bird: 1845

A-wun-ne-wa-be,

Bird of Thunder: 1845

Painted in Paris in 1845. Catlin lists another portrait of Bird of Thunder among those commissioned by Louis Philippe in 1845 and the subject appears again in cartoon 61 (National Gallery of Art).

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

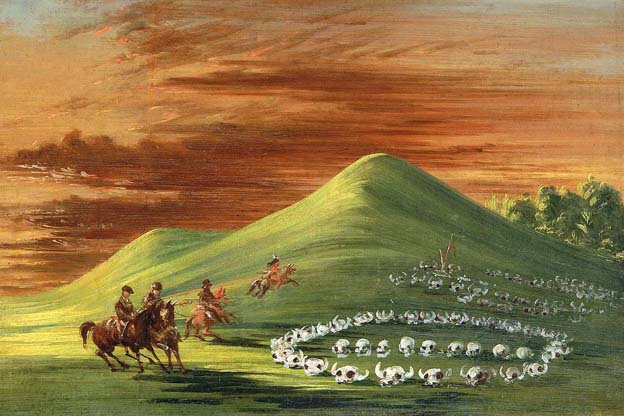

Back View of Mandan Village,

Showing the Cemetery: 1832

"These people never bury the dead, but place the bodies on slight scaffolds just above the reach of human hands, and out of the way of wolves and dogs; and they are there left to mould and decay. This cemetery, or place of deposit for the dead, is just back of the village, on a level prairie; and with all its appearances, history, forms, ceremonies, is one of the strangest and most interesting objects to be described in the vicinity of this peculiar race.…"

"When the scaffolds on which the bodies rest, decay and fall to the ground, the nearest relations having buried the rest of the bones, take the skulls, which are perfectly bleached and purified, and place them in circles of an hundred or more on the prairie-placed at equal distances apart (some eight or nine inches from each other), with the faces all looking to the center; where they are religiously protected and preserved in their precise positions from year to year.…"

"There are several of these 'Golgothas' or circles of twenty or thirty feet in diameter, and in the centre of each ring or circle is a little mound of three feet high, on which uniformly rest two buffalo skulls (a male and female); and in the centre of the little mound is erected a 'medicine pole,' about twenty feet high, supporting many curious articles of mystery and superstition, which they suppose have the power of guarding and protecting this sacred arrangement" (Letters and Notes, vol. 1).

Sketched and perhaps painted at the Mandan village in 1832. A drawing of several scaffolds and a circle of skulls appears in the SI sketchbook. Catlin's description of the cemetery represents a curious blend of anthropological and romantic interests.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Ball Players: Date Unknown

Catlin's Classic Book on Indian Life

In 1841 Catlin published, in London, a book titled Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Conditions of the North American Indians. The book, more than 800 pages in two volumes, contained a vast wealth of material gathered during Catlin's travels among the Indians. The book went through a number of editions.

At one point in the book Catlin detailed how the enormous herds of buffalo on the western plains were being destroyed because robes made of their fur had become so popular in eastern cities.

Perceptively noting what today we would recognize as an ecological disaster, Catlin made a startling proposal. He suggested that the government should set aside enormous tracts of western lands to preserve them in their natural state.

George Catlin can thus be credited with first suggesting the creation of National Parks.

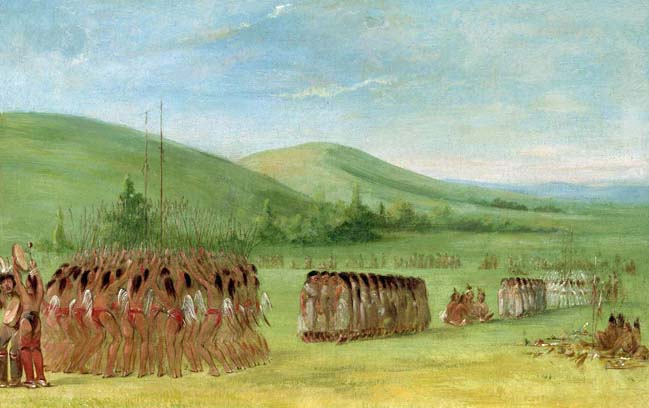

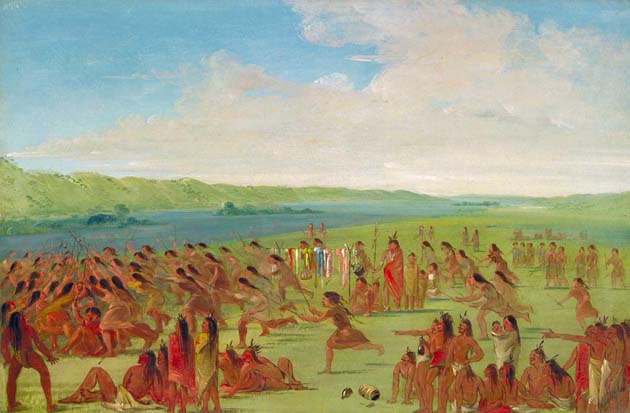

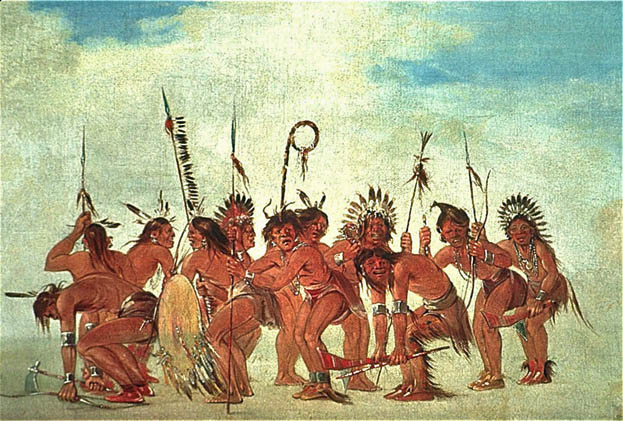

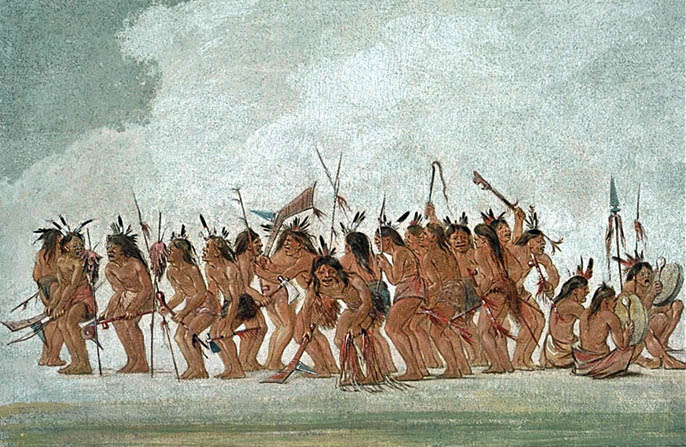

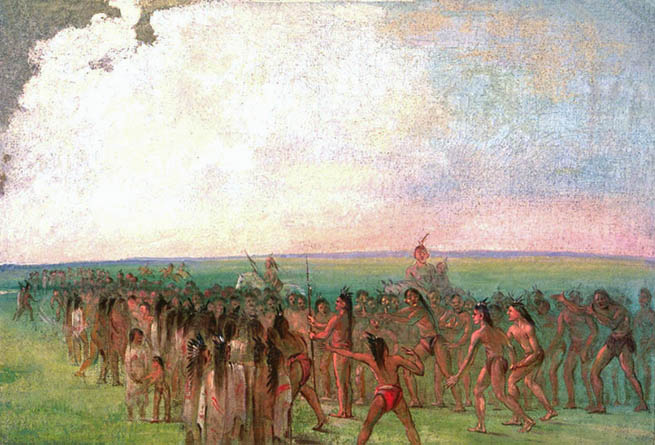

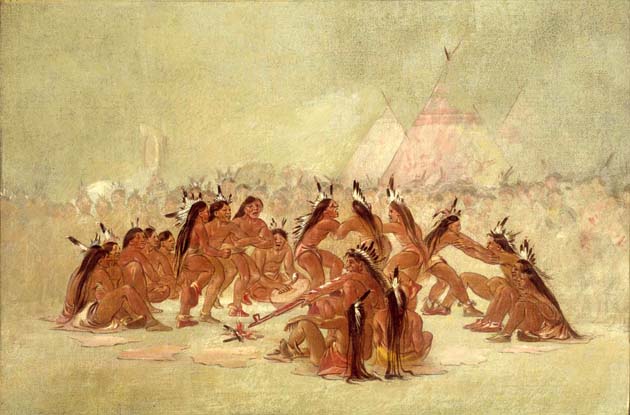

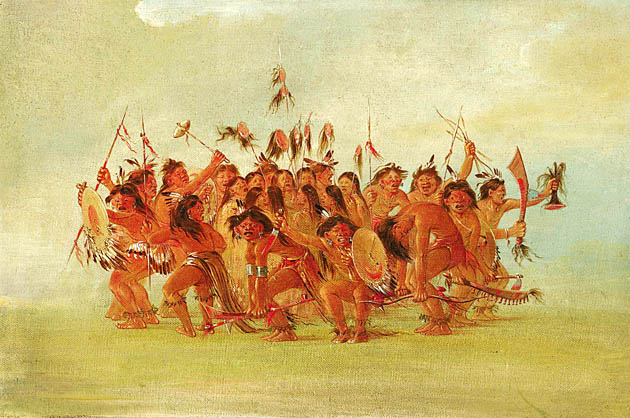

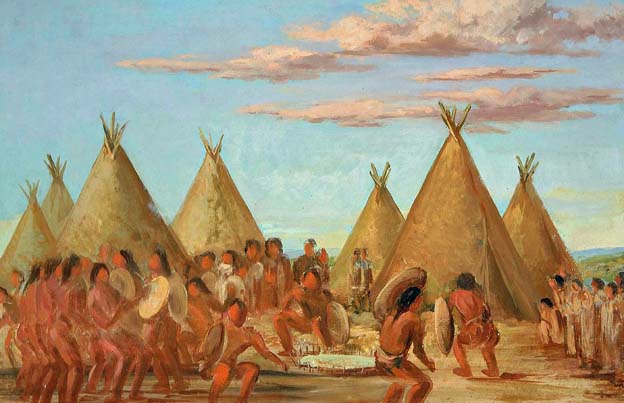

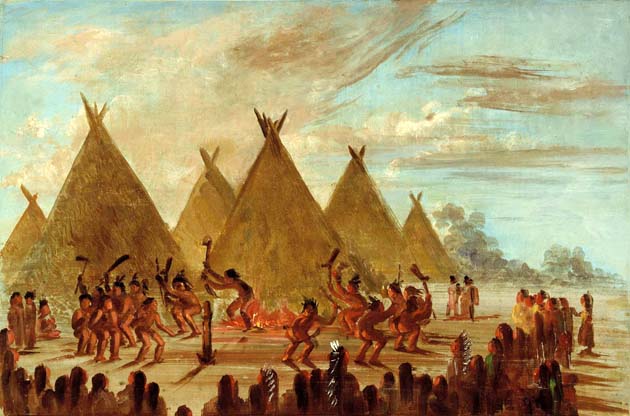

Ball-play Dance, Choctaw: 1834

"The ground having been all prepared and preliminaries of the game all settled, and the betting all made, and the goods all 'staked' night came on … a procession of lighted flambeaux was seen coming from each encampment, to the ground where the players assembled around their respective byes; and at the beat of the drums and chants of the women, each party of players commenced the 'ball-play dance.' Each party danced for a quarter of an hour around their respective byes, in their ball-play dress; rattling their ball-sticks together in the most violent manner, and all singing as loud as they could raise their voices; while the women of each party, who had their goods at stake, formed into two rows on the line between the two parties of players, and danced also, in an uniform step, and all their voices joined in chants to the Great Spirit; in which they were soliciting his favor in deciding the game to their advantage; and also encouraging the players to exert every power they possessed, in the struggle that was to ensue. In the mean time, four old medicine-men, who were to have the starting of the ball, and who were to be judges of the play, were seated at the point where the ball was to be started; and busily smoking to the Great Spirit for their success in judging rightly, and impartially, between the parties in so important an affair" (Letters and Notes, vol. 2, p. 125, pl. 224).

Sketched near Fort Gibson in 1834. Catlin produced a lively rhythm in the ball-play scenes by repeating the pose of figures engaged in a similar action.

The subject is repeated in plate 22 of Catlin's North American Indian Portfolio, first published in 1844, and in cartoon 175. The Schweitzer copy lacks Catlin's animated touch.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

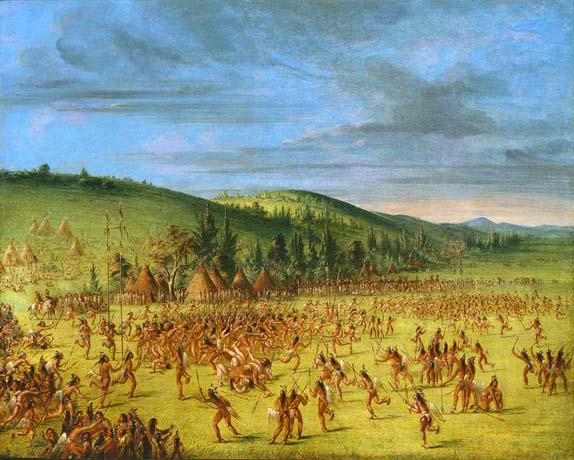

Ball-play of the Choctaw,

Ball Up: 1848

Ball-play of the Choctaw,

Ball Down: 1834

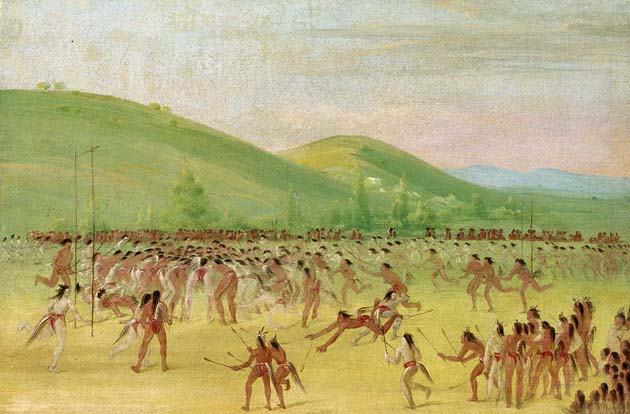

Ball-play of the Women,

Prairie du Chien: 1835

"In the ball-play of the women, they have two balls attached to the ends of a string, about a foot and half long; and each woman has a short stick in each hand, on which she catches the string with the two balls, and throws them, endeavoring to force them over the goal of her own party. The men are more than half drunk, when they feel liberal enough to indulge the women in such an amusement; and take infinite pleasure in rolling about on the ground and laughing to excess, while the women are tumbling about in all attitudes, and scuffling for the ball" (Letters and Notes, vol. 2, p. 146, pl. 252).

Sketched at Prairie du Chien in 1835. The subject is repeated in cartoon 177.

Seth Eastman recorded a similar scene while stationed at Fort Snelling.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Band of Sioux Moving Camp: 1838

"For this strange cavalcade, preparation is made in the following manner: the poles of a lodge are divided into two bunches, and the little ends of each bunch fastened upon the shoulder or withers of a horse, leaving the butt ends to drag behind on the ground on either side. Just behind the horse, a brace or pole is tied across, which keeps the poles in their respective places; and then upon that and the poles behind the horse, is placed the lodge or tent, which is rolled up, and also numerous other articles of household and domestic furniture, and on the top of all, two, three, and even (sometimes) four our women and children! Each one of these horses has a conductress, who sometimes walks before and leads it, with a tremendous pack upon her own back; and at others she sits astride of its back, with a child, perhaps, at her breast, and another astride of the horse's back behind her, clinging to her waist with one arm, while it affectionately embraces a sneaking dog-pup in the other."

"In this way five or six hundred wigwams, with all their furniture, may be seen drawn out for miles, creeping over the grass-covered plains of this country; and three times that number of men, on good horses, strolling along in front or on the flank and every cur who is large enough, and not too cunning to be enslaved, is encumbered with a car or sled on which he patiently drags his load (Letters and Notes, vol. I).

Drawings of a horse and dog dragging poles supporting baggage are in the SI sketchbook (1832), but the painting is not included in the 1837 catalogue. The cursory technique is similar to other examples from the late 1830's.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

George Catlin's Later Life

Catlin returned to the United States, and again tried to get the Congress to buy his paintings. He was unsuccessful. He was swindled in some land investments and was in financial distress. He decided to return to Europe.

In Paris, Catlin managed to settle his debts by selling the bulk of his collection of paintings to an American businessman, who stored them in a locomotive factory in Philadelphia. Catlin's wife died in Paris, and Catlin himself moved on to Brussels, where he would live until returning to America in 1870.

Catlin died in Jersey City, New Jersey in late 1872. His obituary in the New York Times lauded him for his work documenting Indian life, and criticized the Congress for not buying his collection of paintings.

The collection of Catlin paintings stored in the factory in Philadelphia was eventually acquired by the Smithsonian Institution, where it resides today. Other Catlin works are in museums around the United States and Europe.

George Catlin's Indian Gallery/American Art

Remaining Selected Works of George Catlin's Collection

Batiste, Bogard, and I

Approaching Buffalo on the Missouri: 1838

Batiste and I Running Buffalo,

Mouth of the Yellowstone: 1832

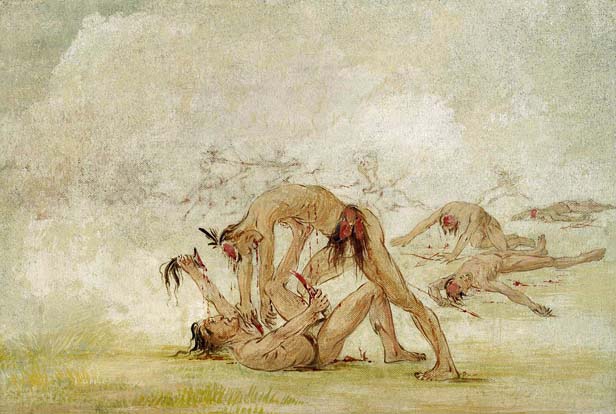

Battle Between Sioux and Sac and Fox: 1847

"The Sioux chief killed and scalped on his horse's back. An historical fact" (1848 catalogue, p. 50).

Painted in Paris 1846-1848. The style is similar to the series commissioned by Louis Philippe, but the subject does not appear on the Travels in Europe list.

A simplified version of the scene is repeated as cartoon 273.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

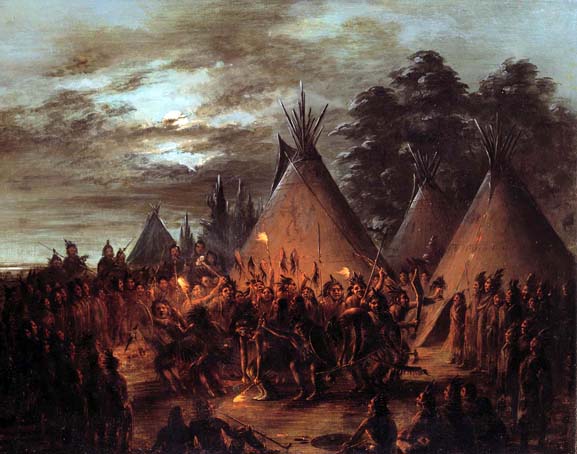

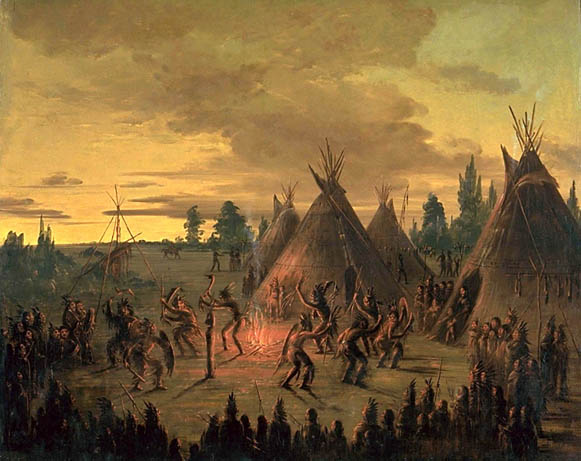

Bear Dance,

Preparing for a Bear Hunt: 1836

"The Sioux, like all the others of these western tribes, are fond of bear's meat, and must have good stores of the 'bear's-grease' laid in, to oil their long and glossy locks, as well as the surface of their bodies. And they all like the fine pleasure of a bear hunt, and also a participation in the bear dance, which is given several days in succession, previous to their starting out, and in which they all join in a song to the Bear Spirit; which they think holds somewhere an invisible existence, and must be consulted and conciliated before they can enter upon their excursion with any prospect of success. For this grotesque and amusing scene, one of the chief medicine-men, placed over his body the entire skin of a bear, with a war-eagle's quill on his head, taking the lead in the dance, and looking through the skin which formed a masque that hung over his face. Many others in the dance wore masques on their faces, made of the skin from the bear's head; and all, with the motions of their hands, closely imitated the movements of that animal; some representing its motion in running, and others the peculiar attitude and hanging of the paws, when it is sitting upon its hind feet, and looking out for the approach of an enemy" (Letters and Notes, vol. I).

Sketched near Fort Pierre in 1832. In the Gilcrease version, the dance takes place in a Sioux village, with members of the tribe looking on and skin lodges in the background. Although the subject does not appear on the Travels in Europe list, this version closely resembles other Paintings commissioned by Louis Philippe. The Smithsonian original matches plate 102 in Letters and Notes.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

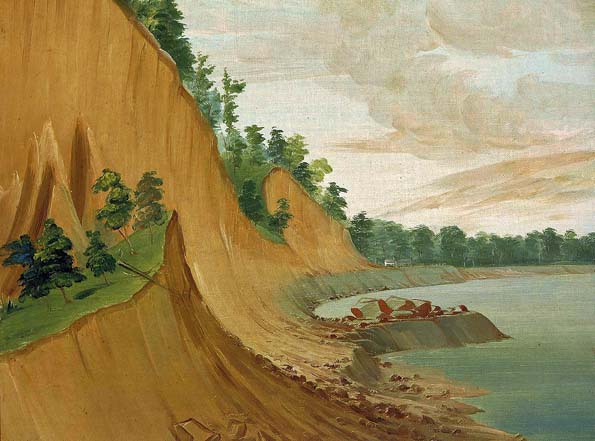

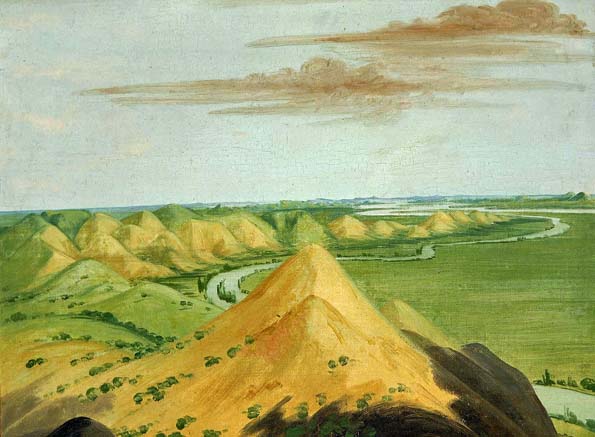

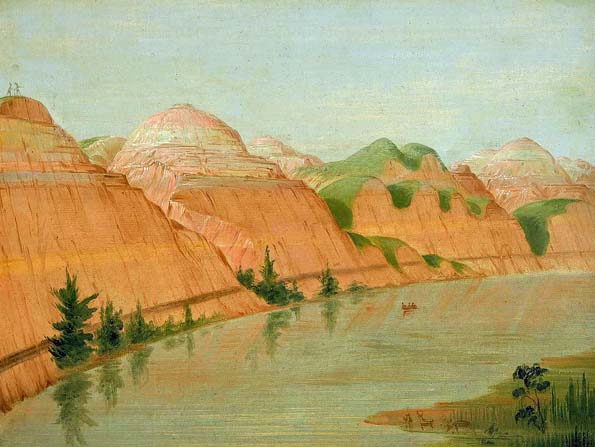

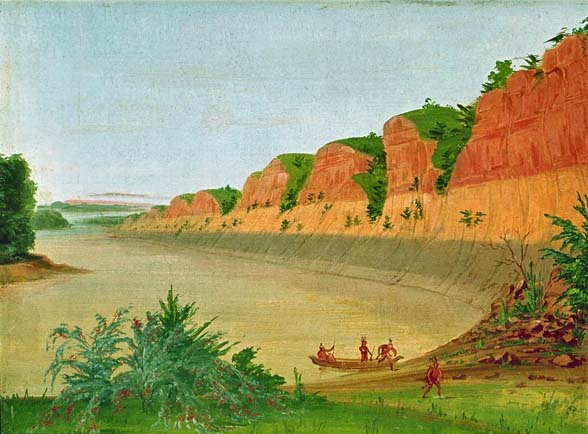

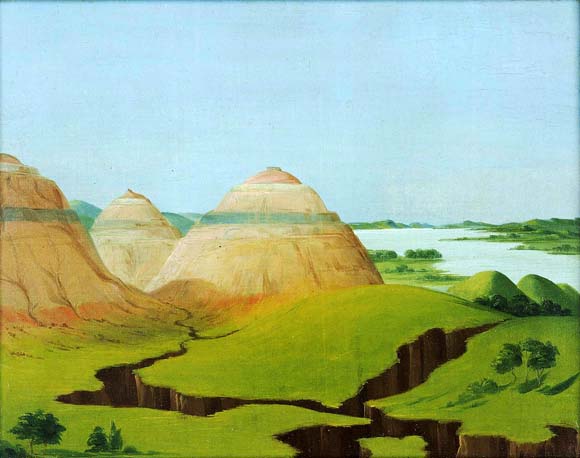

Beautiful Clay Bluffs,

1900 Miles above Saint Louis: 1832

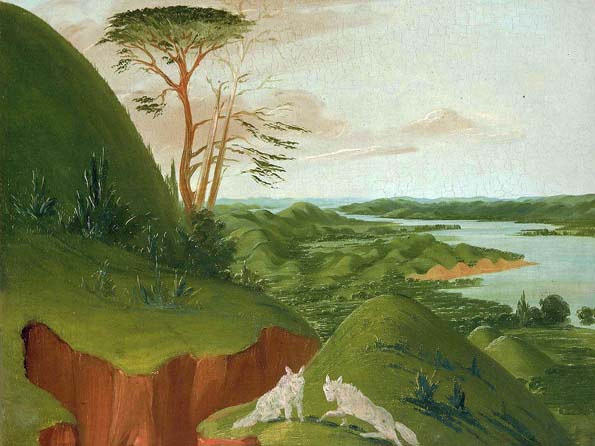

Beautiful Grassy Bluffs,

110 Miles above Saint Louis: 1832

Beautiful Prairie Bluffs above the Poncas,

1050 Miles Above Saint Louis: 1832

"The summit level of the great prairies stretching off to the west and the east from the river, to an almost boundless extent, is from two to three hundred feet above the level of the river; which has formed a bed or valley for its course, varying in width from two to twenty miles. This channel or valley has been evidently produced by the force of the current, which has gradually excavated, in its floods and gorges, this immense space, and sent its debris into the ocean. By the continual overflowing of the river, its deposits have been lodged and left with a horizontal surface, spreading the deepest and richest alluvium over the surface of its meadows on either side; through which the river winds its serpentine course, alternately running from one bluff to the other, which present themselves to its shores in all the most picturesque and beautiful shapes and colors imaginable-some with their green sides gracefully slope down in the most lovely groups to the water's edge" (Letters and Notes, vol. I).

Painted in 1832 on the Missouri River voyage. Catlin's geological interests often determined his selection of subject matter. Matthews says the conformation of the hills is characteristic of that stretch of the river.

The Gilcrease version lacks the number and variety of hills in the Smithsonian original. The latter matches plate 5 in Letters and Notes. The scene is repeated in cartoon 246.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Beautiful Savannah in the Pine Woods of Florida: 1834

Beggar's Dance,

Mouth of Teton River: 1836

"This spirited dance was given, not by a set of beggars but by the first and most independent young men in the tribe, beautifully dressed, (i.e., not dressed at all, except with their breech clouts or kelts, made of eagles' and ravens' quills) with their lances, and pipes, and rattles in their hands, and a medicine-man beating the drum, and joining in the song at the highest key of his voice. In this dance every one sings as loud as he can halloo; uniting his voice with the others, in an appeal to the Great Spirit, to open the hearts of the bystanders to give to the poor, and not to themselves; assuring them that the Great Spirit will be kind to those who are kind to the helpless and poor" (Letters and Notes, vol. I).

Sketched near Fort Pierre in 1832. The scene is repeated in a cartoon incorrectly labeled Chief's Dance-Sioux in the National Gallery catalogue.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Begging Dance,

Sauk and Fox: 1836

Belle Vue, Indian Agency of Major Dougherty,

870 Miles above Saint Louis: 1832

Bi-eets-ee-cure,

Very Sweet Man: 1832

Big Bend on the Upper Missouri,

1900 Miles above Saint Louis: 1832

Bird's eye View of the Mandan Village,

1800 Miles above Saint Louis: 1838

"I have this morning, perched myself upon the top of one of the earth-covered lodges … and having the whole village beneath and about me, with its sachems-its warriors-its dogs-and its horses in motion-its medicines (or mysteries) and scalp-poles waving over my head-its piquets-its green fields and prairies, and river in full view, with the din and bustle of the thrilling panorama that is about me. I shall be able, I hope, to give some sketches more to the life than I could have done from any effort of recollection."

"The groups of lodges around me present a very curious and pleasing appearance, resembling in shape (more nearly than anything else I can compare them to) so many potash-kettles inverted. On the tops of these are to be seen groups standing and reclining, whose wild and picturesque appearance it would be difficult to describe. Stern warriors, like statues, standing in dignified groups, wrapped in their painted robes, with their heads decked and plumed with quills of the war-eagle. … In another direction, the wooing lover. … On other lodges, and beyond these, groups are engaged in games of the 'moccasin,' or the 'platter.' Some are to be seen manufacturing robes and dresses, and others, fatigued with amusements or occupations, have stretched their limbs to enjoy the luxury of sleep, while basking in the sun."

Catlin continues the description of the village over several pages of Letters and Notes (vol. 1) noting, in addition, the drum-like shrine in the center of the open area, the medicine lodge, the paraphernalia and trophies of Indian life, and the scaffolds of the Mandan cemetery in the distance.

The subject is not included in the 1837 catalogue, but does appear in the Egyptian Hall catalogue of January 1840, indicating that it was painted in the interval. Audubon thought Catlin had represented the earth lodges as too regular in size and shape; otherwise, the scene appears to be a unique and vivid account of Mandan village life. The painting is unusually detailed for the late 1830's, and apparently unrelated to a brief drawing of Mandan lodges in the SI sketchbook. The scene is repeated in cartoon 129.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Blackbird's Grave, a Back View,

Prairies Enameled with Flowers: 1832

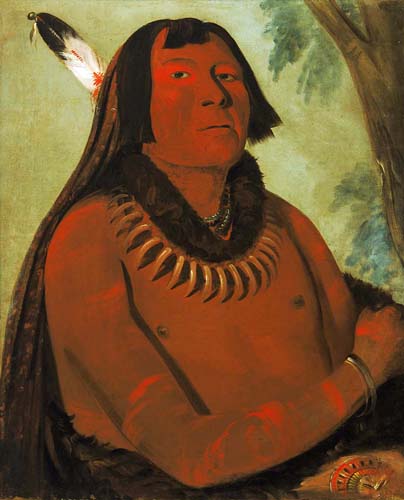

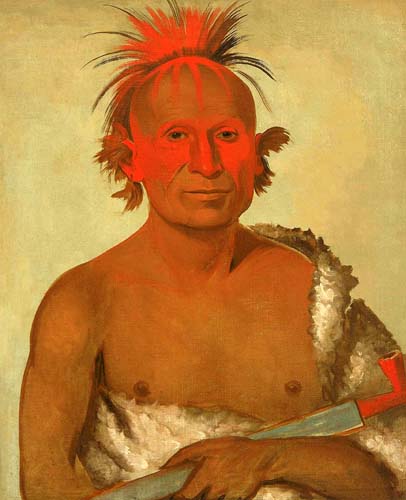

Bód-a-sin,

Chief of the Tribe: 1830

Probably painted at Fort Leavenworth in 1830. The broad, open brushwork has much in common with the technique of the Potawatomi and Kickapoo portraits.

Bód-a-sin appears again in cartoon 63, with his wife and another Delaware chief.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Bogard, Batiste, and I,

Traveling through a Missouri Bottom: 1838

Bogard, Batiste, and I

Chasing Buffalo in High Grass on a Missouri Bottom: 1838

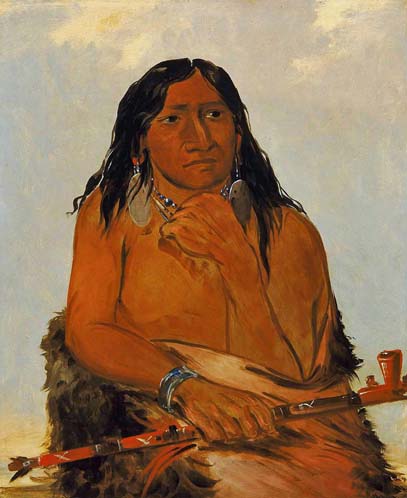

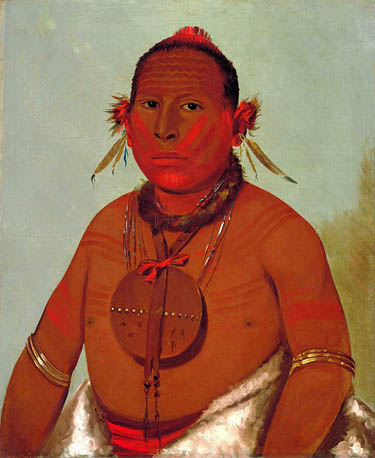

Bón-són-gee,

New Fire, a Band Chief: 1834

Catlin calls New Fire "a very good man" and describes the ornaments hanging on his breast as a boar's tusk and a war whistle (Letters and Notes, vol. 2).

Painted at the Comanche village in 1834. The subject's broadly brushed features have much in common with number 62 and several Comanche portraits.

In the Gilcrease watercolor, New Fire is shown three-quarter length, seated in a landscape. He appears again, full length, in cartoon 69.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Braves Dance, Ojibwa: 1836

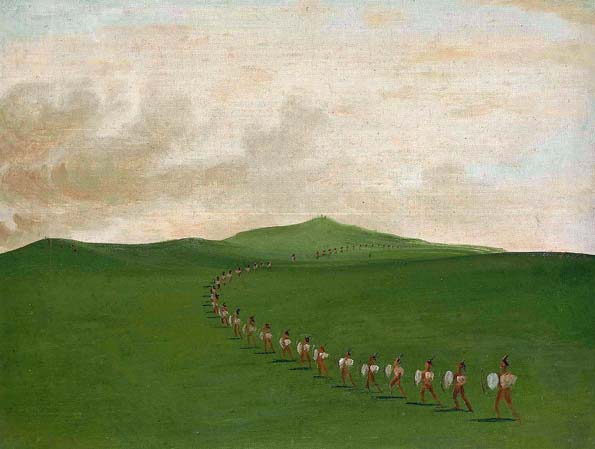

Braves' Dance at Fort Snelling: 1836

The Brave's Dance is peculiarly beautiful, and exciting to the feelings in the highest degree.

At intervals they stop, and one of them steps into the ring, and vociferates as loud as possible, with the most significant gesticulations, the feats of bravery which he has performed during his life-he boasts of the scalps he has taken-of the enemies he has vanquished, and at the same time carries his body through all the motions and gestures, which have been used during these scenes when they were transacted. At the end of his boasting, all assent to the truth of his story, and give in their approbation by the guttural 'waugh!' and the dance again commences. At the next interval, another makes his boasts, and another, and another, and so on" (Letters and Notes, vol. 2, pp. 130-36).

Sketched at Fort Snelling in 1835. The scene is repeated as a War Dance in plate 29 of Catlin's North American Indian Portfolio, first published in 1844.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Bread, Chief of the Tribe: 1831

"He is a shrewd and talented man, well educated-speaking good English-is handsome, and a polite and gentlemanly man in his deportment" (Letters and Notes, vol. II). Catlin also describes Bread as "half-blood" (1848 catalogue, p. 29).

Probably painted in Washington in early 1831, as the size and style of the portrait so closely match the Seneca and Menominee series. Moreover, Bread's name appears on a treaty signed in Washington January 20, 1831, to determine the removal of certain New York tribes to land west of Green Bay, where Catlin locates the chief in the 1837 catalogue.

The artist apparently devoted some time to painting Bread, as the portrait is one of the most perceptive and carefully finished of the period. The subject also appears, full length, in cartoon 62, with his sister and a Tuscarora missionary.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Breaking Down the Wild Horse: 1834

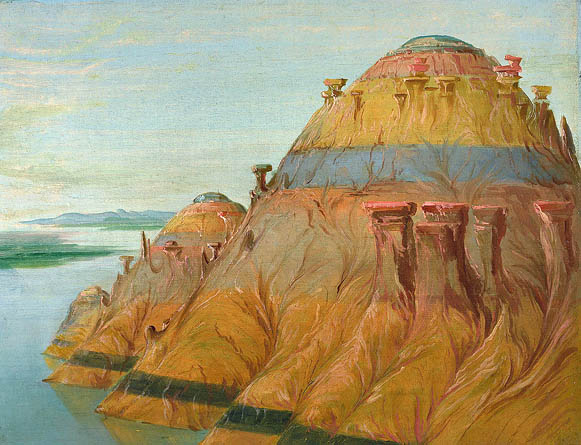

Brick Kilns, Clay Bluffs

1900 Miles above Saint Louis: 1832

As he traveled up the Missouri River, Catlin encountered novel land forms, never seen east of the Mississippi. Among these were the "Brick Kilns", visible from miles away because of their striking red color. They had been named by trappers, who had first seen these clay banks, which the river eroded into a series of tall, fantastically shaped, colorfully striated bluffs. Catlin was an amateur geologist, and when he found a layer of red pumice on top of the formations, decided they were volcanic in origin.

"By the action of water, or other power, the country seems to have been graded away; leaving occasionally a solitary mound or bluff, rising in a conical form to the height of two or three hundred feet, generally pointed or rounded at the top, and in some places grouped together in great numbers . . . the sides of these conical bluffs (which are composed of strata of different colored clays), are continually washing down by the effect of the rains and melting of the frost; and the superincumbent masses of pumice and basalt are crumbling off, and falling down to their bases; and from thence, in vast quantities, by the force of the gorges of water which are often cutting their channels between them-carried into the river, which is close by" (Letters and Notes, Letter No. 10).

Awed by the visual beauty before him, Catlin cannot suppress his scientific curiosity about how it evolved.

Quoted From: Campfire Stories with George Catlin

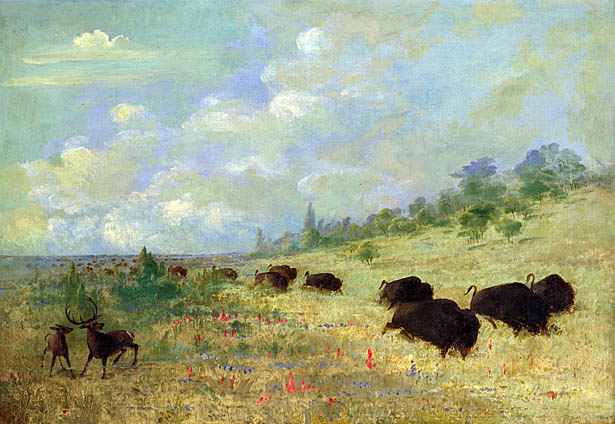

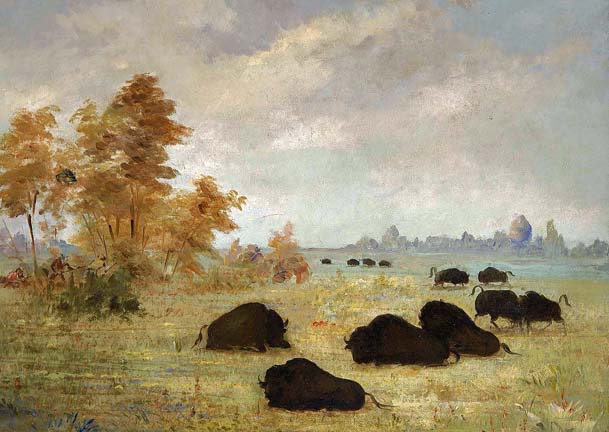

Buffalo Bull Grazing: 1845

Buffalo Bull, Grazing on the Prairie: 1832

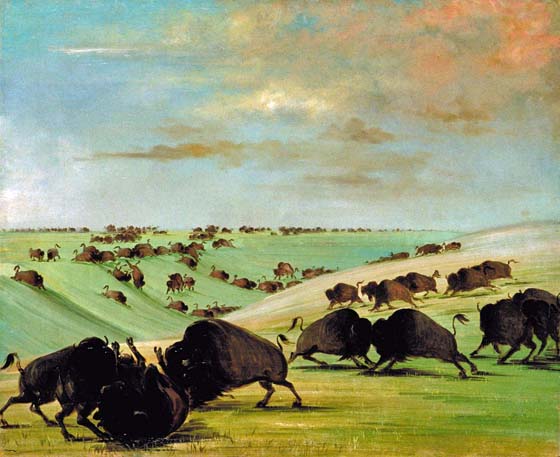

Buffalo Bulls Fighting in Running Season,

Upper Missouri: 1837

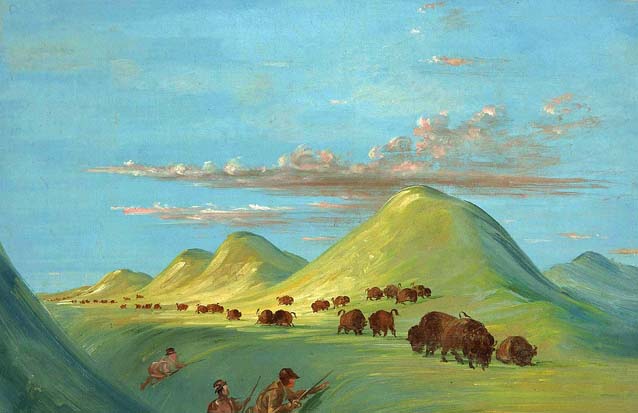

Catlin recounted that the "buffalo graze in immense and almost incredible numbers at times, and roam about and over vast tracts of country, from East to West, and from West to East, as often as from North to South" with the seasons, following the sweetest and most abundant grass. The Plains tribes, dependent on them for food, shelter, tools, and every other necessity of existence, migrated with them.

Quoted From: Campfire Stories with George Catlin

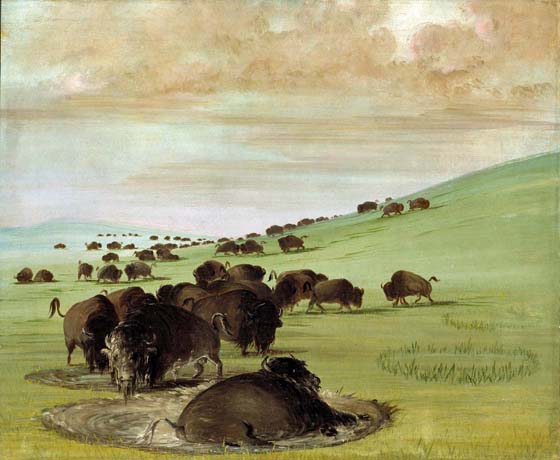

Buffalo Bulls in a Wallow: 1837

Catlin certainly enjoyed hunting with the Indians, and described his own exploits in bringing down buffalo with gusto and graphic detail. He observed, with equally minute attention, that the buffalo provided everything the Plains Indian needed: "There are, by a fair calculation, more than 300,000 Indians, who are now subsisted on the flesh of the buffaloes, and by those animals supplied with all the luxuries of life. The great variety of uses to which they convert the body and other parts of that animal, are almost incredible to the person who has not actually dwelt among these people, and closely studied their modes and customs. Every part of their flesh is converted into food, in one shape or another, and on it they entirely subsist. The robes of the animals are worn by the Indians instead of blankets-their skins when tanned, are used as coverings for their lodges, and for their beds; undressed, they are used for constructing canoes-for saddles, for bridles-lariats, lassos, and thongs. The horns are shaped into ladles and spoons-the brains are used for dressing the skins -their bones are used for saddle trees - for war clubs, and scrapers for graining the robes-and others are broken up for the marrow-fat which is contained in them. Their sinews are used for strings and backs to their bows-for thread to string their beads and sew their dresses. The feet of the animals are boiled, with their hoofs, for the glue they contain, for fastening their arrow points, and many other uses. The hair from the head and shoulders, which is long, is twisted and braided into halters, and the tail is used for a fly brush. In this wise do these people convert and use the various parts of this useful animal, and with all these luxuries of life about them, and their numerous games, they are happy (God bless them) in the ignorance of the disastrous fate that awaits them" (Letters and Notes, Letter No. 31).

Catlin came to believe that the buffalo would be wiped out, which raised another question in his mind: "When the buffaloes shall have disappeared in his country, which will be within eight or ten years, I would ask, who is to supply [the Indian] with the necessaries of life then? and I would ask, further, (and leave the question to be answered ten years hence), when the skin shall have been stripped from the back of the last animal, who is to resist the ravages of 300,000 starving savages; and in their trains, 1,500,000 wolves, whom direst necessity will have driven from their desolate and game-less plains, to seek for the means of subsistence along our exposed frontier? God has everywhere supplied man in a State of Nature, with the necessaries of life, and before we destroy the game of his country, or teach him new desires, he has no wants that are not satisfied" (Letters and Notes, Letter No. 31). The end was not exactly as Catlin predicted, but he was nearly correct about the fate of the buffalo. Modern experts estimate that the buffalo herds in the 1830's were between forty and sixty million head; it is almost inconceivable that within fifty years, that number would be reduced to less than five thousand.

Quoted From: Campfire Stories with George Catlin

Buffalo Chase in Snowdrifts,

Indians Pursuing on Snowshoes: 1832

Buffalo Chase in Winter,

Indians on Snowshoes: 1832

Buffalo Chase over Prairie Bluffs: 1832

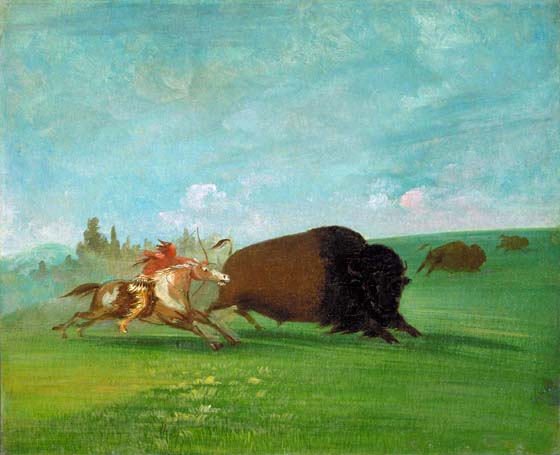

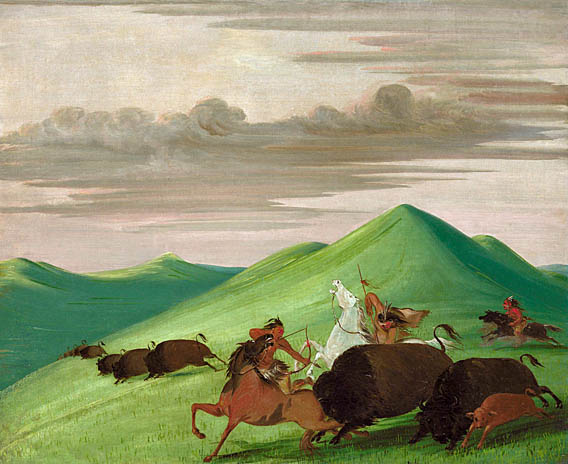

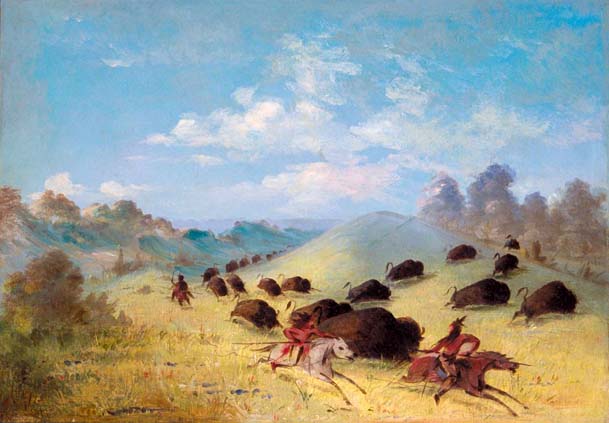

Buffalo Chase with Bows and Lances: 1832

When Catlin went West in the 1830's, he encountered peoples still living on their homelands. He was thrilled to see their freedom and praised their grace and beauty. "No man's imagination, with all the aids of description that can be given to it, can ever picture the beauty and wildness of scenes that may be daily witnessed in this romantic country; of hundreds of these graceful youths, without a care to wrinkle, or a fear to disturb the full expression of pleasure and enjoyment that beams upon their faces - their long black hair mingling with their horses' tails, floating in the wind, while they are flying over the carpeted prairie, and dealing death with their spears and arrows, to a band of infuriated buffaloes; or their splendid procession in a war parade, arrayed in all their gorgeous colors and trappings, moving with most exquisite grace and manly beauty, added to that bold defiance which man carries on his front, who acknowledges no superior on earth, and who is amenable to no laws except the laws of God and honor."

Source: Letters and Notes, No. 2.

Quoted From: Campfire Stories with George Catlin

Buffalo Chase, a Single Death: 1832

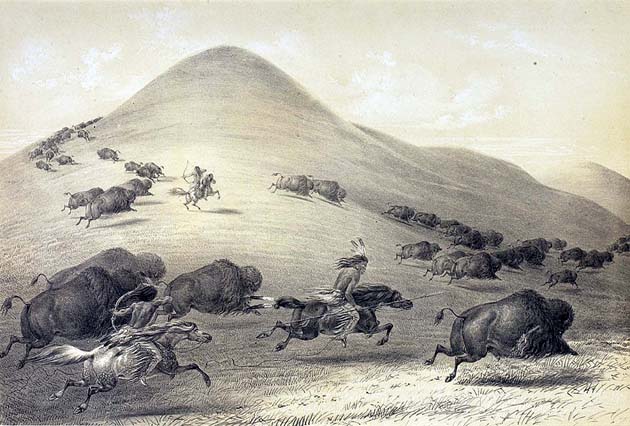

Buffalo Chase, Surrounded by the Hidatsa: 1832

We soon descried at a distance, a fine herd of buffaloes grazing, when a halt and a council were ordered and the mode of attack was agreed upon. I had armed myself with my pencil and my sketchbook only, and consequently took my position generally in the rear, where I could see and appreciate every maneuver.

The plan of attack, which in this country is familiarly called a 'surround,' was explicitly agreed upon, and the hunters who were all mounted on their 'buffalo horses' and armed with bows and arrows or long lances, divided into two columns, taking opposite directions, and drew themselves gradually around the herd at a mile or more distance from them; thus forming a circle of horsemen at equal distances apart, who gradually closed in upon them with a moderate pace, at a signal given. The unsuspecting herd at length 'got the wind' of the approaching enemy and fled in a mass in the greatest confusion. … I had rode up in the rear and occupied an elevated position at a few rods distance, from which I could … survey from my horse's back, the nature and the progress of the grand meleé … a cloud of dust was soon raised, which in parts obscured the throng where the hunters were galloping their horses around and driving the whizzing arrows or their long lances to the hearts of these noble animals; which in many instances, becoming infuriated with deadly wounds in their sides, erected their shaggy manes over their blood-shot eyes and furiously plunged forwards at the sides of their assailants' horses, sometimes goring them to death at a lunge, and putting their dismounted riders to flight for their lives; sometimes their dense crowd was opened, and the blinded horsemen, too intent on their prey amidst the cloud of dust, were hemmed and wedged in amidst the crowding beasts, over whose backs they were obliged to leap for security, leaving their horses to the fate that might await them" (Letters and Notes, vol. 1, pp. 199-200, pl. 79).

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Buffalo Chase, Bull Protecting a Cow and Calf: 1832

Buffalo Chase, Bulls Making Battle with Men and Horses: 1832

Buffalo Chase, Mouth of the Yellowstone: 1832

Buffalo Cow Grazing on the Prairie: 1832

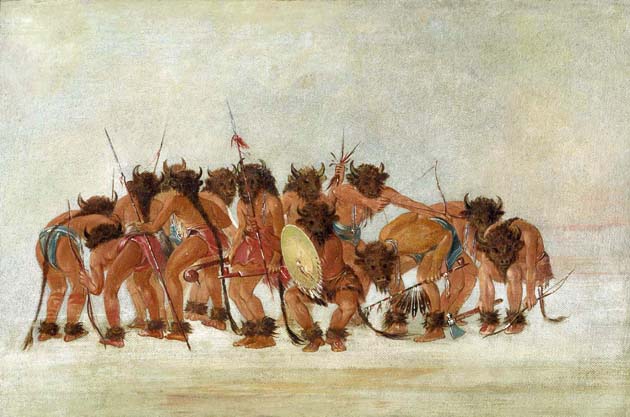

Buffalo Dance, Mandan: 1836

"The (buffalo) mask is put over the head, and generally has a strip of the skin hanging to it, of the whole length of the animal, with the tail attached to it, which, passing down over the back of the dancer, is dragging on the ground. When one becomes fatigued of the exercise, he signifies it by bending quite forward, and sinking his body towards the ground; when another draws a bow upon him and hits him with a blunt arrow, and he falls like a buffalo-is seized by the bye-standers, who drag him out of the ring by the heels, brandishing their knives about him; and having gone through the motions of skinning and cutting him up, they let him off, and his place is at once supplied by another, who dances into the ring with his mask on; and by this taking of places, the scene is easily kept up night and day, until the desired effect has been produced, that of 'making buffalo come' " (Letters and Notes, vol. I).

Sketched in 1832 at the Mandan village. The scene is repeated in plate 8 of Catlin's North American Indian Portfolio, first published in 1844; in plate 70 of the Gilcrease Souvenir album; and in cartoon 171.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Buffalo Herds Crossing the Upper Missouri: 1832

The prairie ecosystem supported flocks of birds, extensive prairie dog towns, and vast herds of game, including elk, antelope, deer, and especially buffalo. Over and over, Catlin describes the size of the herds and the strength and power of the beasts themselves. "Near the mouth of White River, we met the most immense herd crossing the Missouri River-and from an imprudence got our boat into imminent danger among them, from which we were highly delighted to make our escape. It was in the midst of the 'running season', and we had heard the 'roaring' (as it is called) of the herd, when we were several miles from them. When we came in sight, we were actually terrified at the immense numbers that were streaming down the green hills on one side of the river, and galloping up and over the bluffs on the other. The river was filled, and in parts blackened, with their heads and horns, as they were swimming about . . . furiously hooking and climbing on to each other. I rose in my canoe, and by my gestures and hallooing, kept them from coming in contact with us, until we were out of their reach." (Letters and Notes, Letter No. 32)

Quoted From: Campfire Stories with George Catlin

Buffalo Hunt Surround no 9: Date Unknown

Buffalo Hunt under the Wolf-Skin Mask: 1832

Buffalo Hunt, Chase no 6: Date Unknown

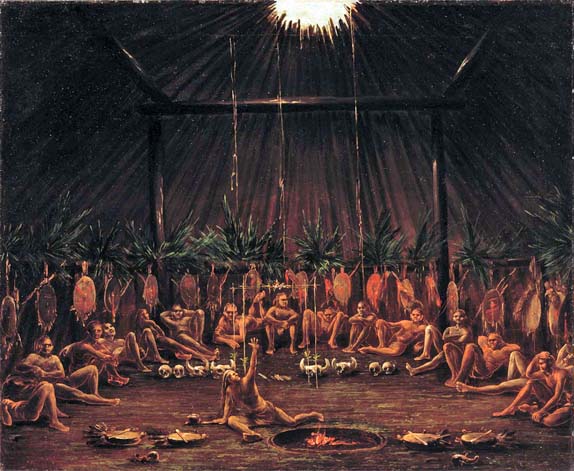

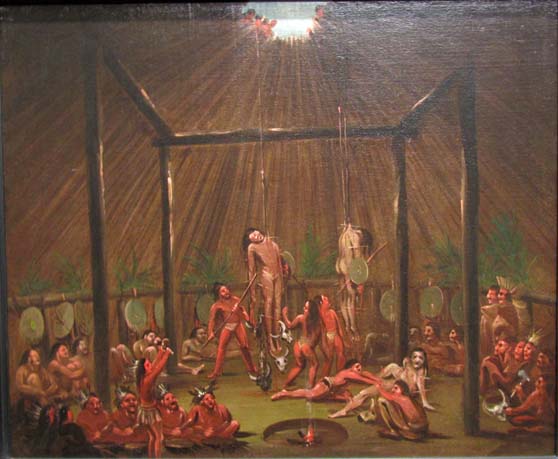

Bull Dance, Mandan O-kee-pa Ceremony: 1832

"During the first three days of this solemn conclave," Catlin continues, "there were many very curious forms and amusements enacted in the open area in the middle of the village, and in front of the medicine-lodge, by other members of the community, one of which formed a material part or link of these strange ceremonials. This very curious and exceedingly grotesque part of their performance, which they denominated … the bull-dance, of which I have before spoken, as one of the avowed objects for which they held this annual féte; and to the strictest observance of which they attribute the coming of buffaloes to supply them with food during the season-is repeated four times during the first day, and sixteen times on the fourth day; and always around the curb, or 'big canoe' (the drum-like shrine in the center of the open area)."

"This subject I have selected for my second picture, and the principal actors in it were eight men, with the entire skins of buffaloes thrown over their backs, with the horns and hoofs and tails remaining on; their bodies in a horizontal position, enabling them to imitate the actions of the buffalo, while they were looking out of its eyes as through a mask."

"The bodies of these men were chiefly naked and all painted in the most extraordinary manner, with the nicest adherence to exact similarity; their limbs, bodies and faces, being in every part covered, either with black, red, or white paint. Each one of these strange characters had also a lock of buffalo's hair tied around his ankles-in his right hand a rattle, and a slender white rod or staff, six feet long, in the other; and carried on his back, a bunch of green willow boughs about the usual size of a bundle of straw. These eight men, being divided into four pairs, took their positions on the four different sides of the curb or big canoe, representing thereby the four cardinal points; and between each group of them, with the back turned to the big canoe, was another figure, engaged in the same dance, keeping step with them, with a similar staff or wand in one hand and a rattle in the other, and (being four in number) answering again to the four cardinal points. The bodies of these four young men were chiefly naked, with no other dress upon them than a beautiful kelt (or quartz-quaw), around the waist, made of eagles quills and ermine, and very splendid headdresses made of the same materials. Two of these figures were painted entirely black with pounded charcoal and grease, whom they called the 'firmament or night,' and the numerous white spots which were dotted all over their bodies, they called 'stars.' The other two were painted from head to foot as red as vermilion could make them; these they said represented the day, and the white streaks which were painted up and down over their bodies, were 'ghosts which the morning rays were chasing away' " (Letters and Notes, vol. I).

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Butte de Mort, Sioux Burial Ground,

Upper Missouri: 1838

Cabane's Trading House, 930 Miles above Saint Louis: 1832

Caddo Indians Chasing Buffalo, Cross Timbers, Texas: 1847

Painted in Paris 1846-1848. The Cross Timbers area extends into southern Oklahoma, where Catlin saw many such chases. Cartoon 360 is a similar or related view.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Cah-be-mub-bee,

He Who Sits Everywhere, a Brave: 1845

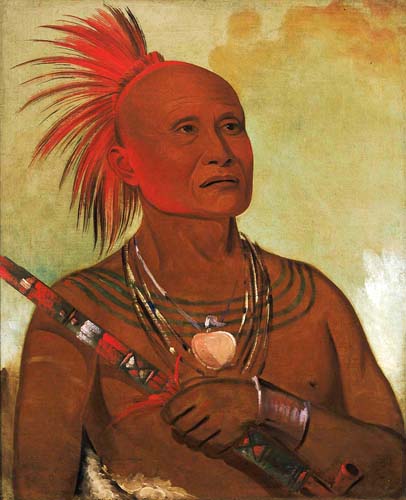

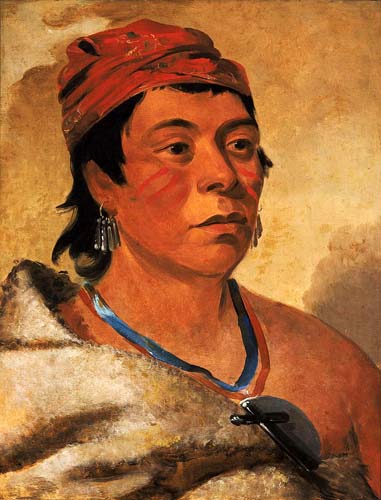

Cah-he-ga-shín-ga,

Little Chief: 1834

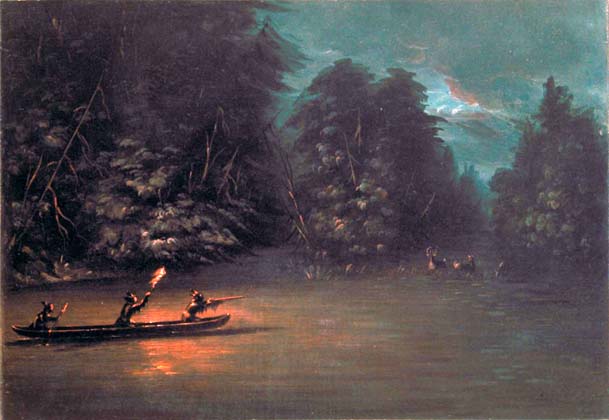

Canoe Race Near Sault Ste. Marie: 1836

"In plate 267 is seen one of their favorite amusements at this place, which I was lucky enough to witness a few miles below the Sault, when high betting had been made, and a great concourse of Indians had assembled to witness an Indian regatta or canoe race, which went off with great excitement, firing of guns, yelping. The Indians in this vicinity are all Chippewa, and their canoes all made of birch bark, and chiefly of one model; they are exceedingly light, as I have before described, and propelled with wonderful velocity" (Letters and Notes, vol. II).

Sketched on Catlin's journey to the Pipestone Quarry in 1836. The scene is repeated in cartoon 335.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Catlin and His Indian Guide

Approaching Buffalo under White Wolf Skins: 1847

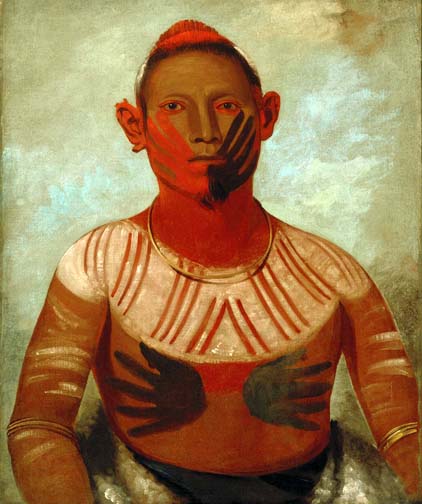

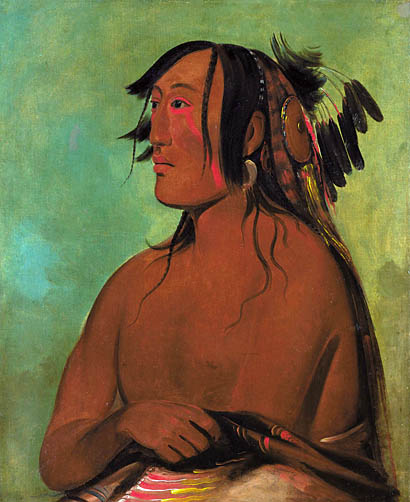

Chah-ee-chopes,

Four Wolves, a Chief in Mourning: 1832

"The grandson also of this sachem, a boy of six years of age, and too young as yet to have acquired a name, has stood forth like a tried warrior; and I have painted him at full length, with his bow and quiver slung, and his robe made of a raccoon skin. The history of this child is somewhat curious and interesting; his father is dead, and in case of the death of the chief … he becomes hereditary chief of the tribe. This boy has been twice stolen away by the Crows by ingenious stratagems, and twice re-captured by the Blackfeet, at considerable sacrifice of life, and at present he is lodged with Mr. M'Kenzie, for safekeeping and protection, until he shall arrive at the proper age to take the office to which he is to succeed" (Letters and Notes, vol. 1, p. 30, pl. 12).

Painted at Fort Union in 1832. The true proportions of such a diminutive figure were still beyond Catlin's reach, but the appealing roundness of the little boy effectively conveys his age. The face and figure in the Gilcrease portrait are only a stylized approximation of the original.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Cha-tee-wah-nee-che, No Heart,

Chief of the Wah-ne-watch-to-nee-nah Band: 1832

Chee-a-ex-e-co,

Daughter of Deer without a Heart: 1838

Chee-ah-ka-tchee,

Wife of Not-to-way: 1835

Chee-me-nah-na-quet,

Great Cloud, son of Grizzly Bear: 1831

Chee-me-nah-na-quet,

Great Cloud, son of Grizzly Bear: 1831

Chin-cha-pee,

Fire Bug That Creeps, Wife of Pigeon's Egg Head: 1832

"A fine looking squaw, in a handsome dress of the mountain-sheep skin, holding in her hand a stick curiously carved, with which every woman in this country is supplied; for the purpose of digging up the … prairie turnip" (Letters and Notes, vol. 1, p. 56, pl. 29).

Painted at Fort Union in 1832. The subject appears again, full length, in cartoon 75, with her husband.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Clay Bluffs, Twenty Miles above the Mandans: 1832

Cler-mont, First Chief of the Tribe: 1834

Co-ee-ha-jo,

a Chief: 1838

Cól-lee, a Band Chief: 1834

"An aged and dignified chief. … This man … as well as a very great proportion of the Cherokee population, has a mixture of red and white blood in his veins, of which, in this instance, the first seems decidedly to predominate" (Letters and Notes, vol. 2, p. 119, pl. 217).

Painted at Fort Gibson in 1834. Catlin refers to the subject as Jol-lee in Letters and Notes.

The oil portrait has been modeled with a vivacity and assurance that almost equals number 284, but the Gilcrease watercolor, for once, also looks much like a life study (fig. 146). The subject is half-length in the latter, and a chair back is visible behind his right shoulder. The Smithsonian portrait more closely resembles plate 217 in Letters and Notes.

Cól-lee appears again, full length, in cartoon 71.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Comanche Feats of Horsemanship: 1834

Comanche Giving Arrows to the Medicine Rock: 1838

"A curious superstition of the Comanche: going to war, they have no faith in their success, unless they pass a celebrated painted rock, where they appease the spirit of war (who resides there), by riding by it at full gallop, and sacrificing their best arrow by throwing it against the side of the ledge" (1848 catalogue, pp. 40-44).

The painting is not included in the 1837 catalogue, and the brushwork is the same as in number 471, indicating a similar date of execution. Catlin used a wide range of techniques in the late 1830's, depending on the subject and the time he wished to devote to an individual painting.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Comanche Indians Chasing Buffalo with Lances and Bows: 1846

Catlin enjoyed and documented buffalo hunts with various tribes, describing methods such as the exhilarating but dangerous chase on horseback, the surround, and the ambush, in which hunters crept among the unsuspecting herds disguised under the skin of a white wolf for a close and easy shot. While many Indians still used the ambush in the 1830's, the acquisition of the horse shaped both hunting methods and the larger Plains culture. Not only could they hunt with less danger to themselves and greater hope of success, they were able to keep and transport far larger volumes of possessions. Catlin noted that contact with white traders and settlers created 'artificial' needs, which were satisfied by trading buffalo robes for whiskey and other goods. He remarked that "the Sioux are a bold and desperate set of horsemen, and great hunters; and in the heart of their country is one of the most extensive assortments of goods, of whiskey, and other saleable commodities, as well as a party of the most indefatigable men, who are constantly calling for every robe that can be stripped from the buffalos' backs" (Letters and Notes, Letter No. 31). Already in Catlin's time, Plains Indians were killing bison in increasing numbers (and taking extra wives to prepare the hides) to take advantage of new trading opportunities.

Quoted From: Campfire Stories with George Catlin

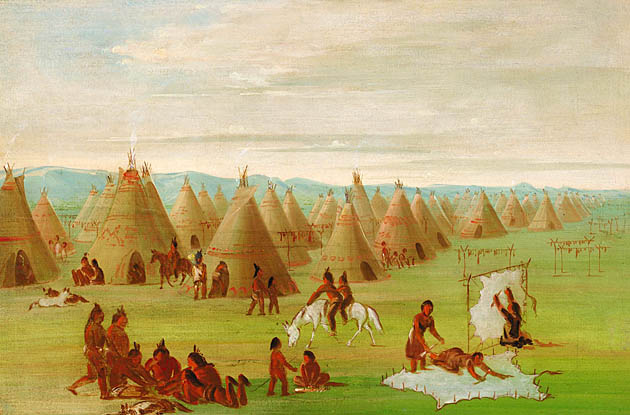

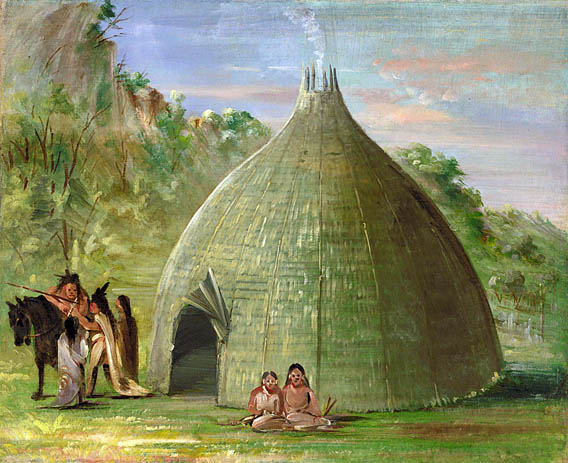

Comanche Lodge of Buffalo Skins: 1834

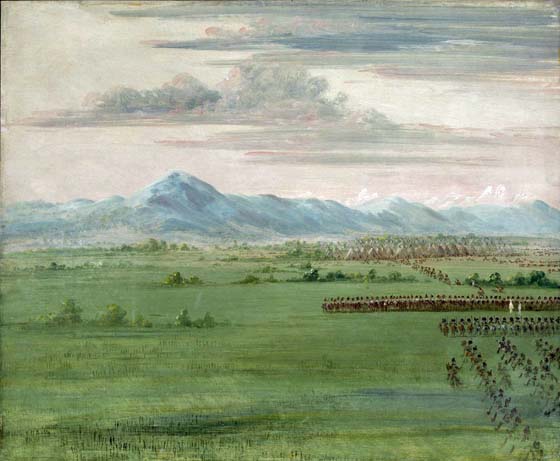

Comanche Meeting the Dragoons: 1834

"Colonel Dodge ordered the command to halt, while he rode forward with a few of his staff, and an ensign carrying a white flag. I joined this advance, and the Indians stood their ground until we had come within half a mile of them, and could distinctly observe all their numbers and movements. We then came to a halt, and the white flag was sent a little in advance, and waved as a signal for them to approach; at which one of their party galloped out in advance of the war-party, on a milk white horse, carrying a piece of white buffalo skin on the point of his long lance in reply to our flag.

"This moment was the commencement of one of the most thrilling and beautiful scenes I ever witnessed. All eyes, both from his own party and ours, were fixed upon the maneuvers of this gallant little fellow, and he well knew it.

"The distance between the two parties was perhaps half a mile, and that a beautiful and gently sloping prairie; over which he was for the space of a quarter of an hour, reining and spurring his maddened horse, and gradually approaching us by tacking to the right and the left, like a vessel beating against the wind. He at length came prancing and leaping along till he met the flag of the regiment, when he leaned his spear for a moment against it, looking the bearer full in the face, when he wheeled his horse, and dashed up to Colonel Dodge with his extended hand, which was instantly grasped and shaken. We all had him by the hand in a moment, and the rest of the party seeing him received in this friendly manner, instead of being sacrificed, as they undoubtedly expected, started under 'full whip' in a direct line toward us" (Letters and Notes, vol. 2, pp. 50-56, pl. 157).

Sketched on the dragoon expedition in 1834. Catlin often communicated the visual impact of such events more effectively in his written descriptions than in his paintings.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Comanche Moving Camp, Dog Fight Enroute: 1834

Catlin wrote that the Indians would move their camp six or eight times in a summer to follow the buffalo herds. He admired the efficiency of their methods, as he depicted a routine that had been in place for generations. "The poles of a lodge are divided into two bunches, and the little ends of each bunch fastened upon the shoulder or withers of a horse, leaving the butt ends to drag behind on the ground on either side. Just behind the horse, a brace or pole is tied across, which keeps the poles in their respective places; and then upon that and the poles behind the horse, is placed the lodge or tent, which is rolled up, and also numerous other articles of household and domestic furniture, and on the top of all, two, three, and even (sometimes) four our women and children! Each one of these horses has a conductress, who sometimes walks before and leads it, with a tremendous pack upon her own back" (Letters and Notes, Letter No. 7).

Catlin often described the Indians' affectionate family relationships and admirable qualities such as nobility or humor. "Each horse drags his load, and each dog, i.e. each dog that will do it (and there are many that will not), also dragging his wallet on a couple of poles; and each squaw with her load, and all together cherishing their pugnacious feelings, which often bring them into general conflict, commencing usually among the dogs, and sure to result in fisticuffs of the women; while the men, riding leisurely on the right or the left, take infinite pleasure in overlooking these desperate conflicts, at which they are sure to have a laugh, and in which, as sure never to lend a hand" (Letters and Notes, Letter No. 42). The horse plays an important role in this scene; his ability to pull larger burdens meant that the migration could be accomplished with larger teepee and less human labor.

Quoted From: Campfire Stories with George Catlin

Comanche Village, Women Dressing Robes and Drying Meat: 1834

Comanche War Party, Chief Discovering the

Enemy and Urging his Men at Sunrise: 1834

Comanche War Party, Mounted on Wild Horses: 1835

Probably painted in Catlin's studio between 1835 and 1837. The sketchy figures are unlike other examples from the dragoon expedition, and the foliage is similar to number 495.

The scene is repeated in cartoon 286, with the riders in a somewhat different formation.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Comanche War Party on the March, Fully Equipped: 1847

Painted in Paris 1846-1848. In spite of Catlin's haste, the technique and palette are astonishingly delicate.

The scene is repeated in cartoon 300 (Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon), with the line of warriors moving in the opposite direction.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Comanche Warrior Lancing an Osage,

at Full Speed: 1838

Comanche Warriors, with White Flag,

Receiving the Dragoons: 1834

"In the midst of this lovely valley, we could just discern among the scattering shrubbery that lined the banks of the watercourses, the tops of the Comanche wigwams, and the smoke curling above them. The valley, for a mile distant about the village, seemed speckled with horses and mules that were grazing in it. The chiefs of the war-party requested the regiment to halt, until they could ride in, and inform their people who were coming. We then dismounted for an hour or so; when we could see them busily running and catching their horses; and at length, several hundreds of their braves and warriors came out at full speed to welcome us, and forming in a line in front of us, as we were again mounted, presented a formidable and pleasing appearance. As they wheeled their horses, they very rapidly formed in a line, and 'dressed' like well-disciplined cavalry. The regiment was drawn up in three columns, with a line formed in front, by Colonel Dodge and his staff, in which rank my friend Chadwick and I were also paraded; when we had a fine view of the whole maneuver, which was picturesque and thrilling in the extreme" (Letters and Notes, vol. 2, p. 61, pl. 163).

Sketched in 1834 at the Comanche village. Note the dashes of pigment used to indicate the formations of dragoons and Comanche.

Catlin probably reserved his few healthy hours at the village for portraits. Landscapes of such detail must have been painted after his return to St. Louis and the East.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Coo-coo-coo, The Owl,

an Aged Chief: 1836

Described by Catlin as "a very aged and emaciated chief, whom I painted at Green Bay, in Fort Howard. He had been a distinguished man, but now in his dotage, being more than 100 years old-and a great pet of the surgeon and officers of the post" (Letters and Notes, vol. II).

Painted in 1836 when Catlin stopped at Green Bay on his way to the Pipestone Quarry. Donaldson's date is incorrect. Like the Eastern Sioux and Ojibwa portraits of 1830-1836, in the Menominee series have standard dimensions, and the subjects are shown in quiet, relaxed attitudes. The careful draftsmanship of this painting is less typical of the series than the hasty contours of the numbers that follow.

The Gilcrease and Smithsonian portraits are almost identical, but the face in the latter, as befits the original, is handled with greater conviction. The Owl also appears in cartoon 18, with two young men of the tribe.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Crow Lodge of Twenty-Five Buffalo Skins: 1832

"The Crows, of all the tribes in this region … make the most beautiful lodge … they of ten times dress the skins of which they are composed almost as white as linen, and beautifully garnish them with porcupine quills, and paint and ornament them in such a variety of ways, as renders them exceedingly picturesque and agreeable to the eye. I have procured a very beautiful one of this description, highly-ornamented, and fringed with scalp-locks, and sufficiently large for forty men to dine under. The poles which support it are about thirty in number, of pine, and all cut in the Rocky Mountains, having been some hundred years, perhaps, in use. This tent, when erected, is about twenty-five feet high, and has a very pleasing effect" (Letters and Notes, vol. 1, pp. 40-44, pl. 20).

Sketched, or perhaps painted, at Fort Union in 1832. No figures appear in the Gilcrease version, and the designs on the lodge are different. The Smithsonian original matches plate 20 in Letters and Notes, and the scene is repeated in cartoon 349.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Cú-sick,

Son of the Chief: 1838

Described by Catlin as "a very talented man-has been educated for the pulpit in some one of our public institutions, and is now a Baptist preacher, and I am told a very eloquent speaker" (Letters and Notes, vol. II).

The portrait is not included in the 1837 catalogue, but does appear in the Egyptian Hall catalogue of January 1840, indicating that it may have been painted in the interval. judging from Cú-sick's dress and manner, Catlin did not necessarily encounter him on the Tuscarora reservation near Buffalo, as Donaldson and others have suggested. Cú-sick's features are modeled with a fine, light touch that one sees in Catlin's portraits of white men of the late 1830's.

The subject has no arm bands, necklaces, or sash in plate 202 of Letters and Notes. He appears again, full length, in cartoon 62.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Dance of the Chiefs,

Mouth of the Teton River: 1832

Dance to the Berdash: 1836

"Dance to the Berdashe is a very funny and amusing scene, which happens once a year or more often, as they choose, when a feast is given to the 'Berdashe,' as he is called in French … who is a man dressed in woman's clothes, as he is known to be all his life, and for extraordinary privileges which he is known to possess, he is driven to the most servile and degrading duties, which he is not allowed to escape; and he being the only one of the tribe submitting to this disgraceful degradation, is looked upon as medicine and sacred, and a feast is given to him annually" (Letters and Notes, vol. II).

Sketched at the Sauk and Fox village in 1835. The scene is repeated in cartoon 162.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Dance to the Medicine Bag of the Brave: 1836

"This is a custom well worth recording, for the beautiful moral which is contained in it. In this plate is represented a party of Sac warriors who have returned victorious from battle, with scalps they have taken from their enemies, but having lost one of their party, they appear and dance in front of his wigwam, fifteen days in succession, about an hour on each day, when the widow hangs his medicine-bag on a green bush which she erects before her door, under which she sits and cries, while the warriors dance and brandish the scalps they have taken, and at the same time recount the deeds of bravery of their deceased comrade in arms, while they are throwing presents to the widow to heal her grief and afford her the means of a living" (Letters and Notes, vol. II).

Sketched at the Sauk and Fox village in 1835. The scene is repeated in cartoon 160.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Deep Lake, an Old Chief: 1831

Deer Hunting by Torchlight in Bark Canoes: 1847

Discovery Dance,

Sac and Fox: 1836

"The Discovery Dance has been given here, among various others, and pleased the bystanders very much; it was exceedingly droll and picturesque, and acted out with a great deal of pantomimic effect-without music, or any other noise than the patting of their feet, which all came simultaneously on the ground, in perfect time, while they were dancing forward two or four at a time, in a skulking posture, overlooking the country, and professing to announce the approach of animals or enemies which they have discovered, by giving the signals back to the leader of the dance" (Letters and Notes, vol. II).

Sketched at the Sauk and Fox village in 1835. The scene is repeated in cartoon 167.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

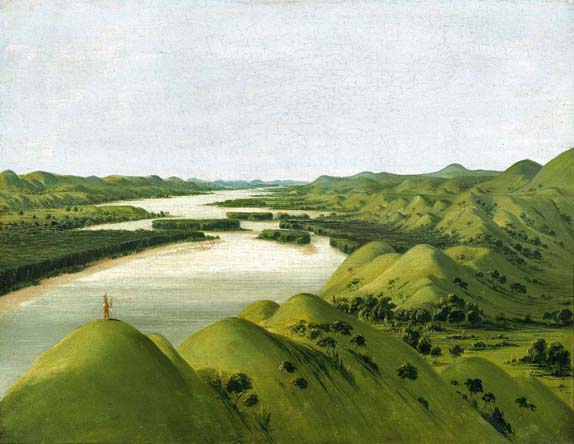

Distant View of the Mandan Village: 1832

"This tribe is at present located on the west bank of the Missouri, about 1800 miles above Saint Louis, and 200 below the Mouth of Yellow Stone river. … The site of the lower (or principal) town … is one of the most beautiful and pleasing that can be seen in the world, and even more beautiful than imagination could ever create. In the very midst of an extensive valley (embraced within a thousand graceful swells and parapets or mounds of interminable green, changing to blue, as they vanish in distance) … on an extensive plain … without tree or bush … are to be seen rising from the ground, and towards the heavens, domes-(not 'of gold,' but) of dirt-and the thousand spears (not 'spires') and scalp-poles, of the semi-subterraneous village of the hospitable and gentlemanly Mandans" (Letters and Notes, vol. I).

Fort Clark, the American Fur Company outpost, is at the left of the village.

Painted in 1832 on Catlin's Missouri River voyage. The landscape details are remarkably close to Karl Bodmer's watercolor of the Mandan village in the winter of 1830-34.

Cartoon 130 is a later edition of the Smithsonian painting, and cartoon 131 (Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon) is a related view.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Dog Dance at Fort Snelling: 1836

Considerable preparation was made for the occasion, and the Indians informed me, that if they could get a couple of dogs that were of no use about the garrison, they would give us their favorite, the 'dog dance'. The two dogs were soon produced by the officers, and in presence of the whole assemblage of spectators, they butchered them and placed their two hearts and livers entire and uncooked, on a couple of crotches about as high as a man's face. These were then cut into strips, about an inch in width, and left hanging in this condition, with the blood and smoke upon them. A spirited dance then ensued; and, in a confused manner, every one sung forth his own deeds of bravery in ejaculatory gutturals, which were almost deafening; and they danced up, two at a time to the stakes, and after spitting several times upon the liver and hearts, caught a piece in their mouths, bit it off and swallowed it. This was all done without losing the step (which was in time to their music), or interrupting the times of their voices" (Letters and Notes, vol. 2, pp. 130-37, pl. 237).

Sketched at Fort Snelling in 1835. Most figures in Catlin's dance groups assume a similar half-crouching position that is repeated at various angles and with different gestures, as the dancers move around a loosely defined circle. The individual figures often have a fixed or static appearance, but the repetition of similar poses does generate a lively rhythm in the groups that becomes a substitute for motion. A corresponding effect may be observed in Catlin's hunting and sporting scenes.

Individual figures and ritual details are described in the dance scenes with a thinly painted, linear clarity unusual for the artist at this period. The technique is much the same throughout the series, indicating a date of execution after 1835, when Catlin saw the dances at Fort Snelling and the Sauk and Fox village. The cartoons that he began painting in the 1850s are of a somewhat similar style.

The Dog Dance is repeated in cartoon 170. Seth Eastman sketched the same dance while stationed at Fort Snelling several years later.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Du-cór-re-a,

Chief of the Tribe, and His Family: 1830

Probably painted at Prairie du Chien in 1830, as the size and style are noticeably different from the earlier Winnebago portraits. The chief died in 1834 so Catlin could not have seen him on one of his later visits to the Upper Mississippi.

This hastily sketched group may have been one of Catlin's first attempts at Indian portraiture in the West. Later that summer he apparently worked in the neighborhood of Fort Leavenworth, with more encouraging results.

Quoted From: The Catlin Collection

Dubuque's Grave,

Upper Mississippi: 1835

Duhk-gits-o-o-see,

Red Bear, a Distinguished Warrior: 1832

Dying Buffalo Bull in a Snowdrift: 1838

Dying Buffalo,

Shot with an Arrow: 1832

Eagle Dance, Choctaw: 1836

"The Eagle Dance, a very pretty scene … [was] got up by their young men, in honor of that bird, for which they seem to have a religious regard. This picturesque dance was given by twelve or sixteen men, whose bodies were chiefly naked and painted white, with white clay, and each one holding in his hand the tail of the eagle, while his head was also decorated with an eagle's quill. Spears were stuck in the ground, around which the dance was performed by four men at a time, who had simultaneously, at the beat of the drum, jumped up from the ground where they. had all sat in rows of four, one row immediately behind the other, and ready to take the place of the first four when they left the ground fatigued.…

"In this dance, the steps or rather jumps, were different from anything I had ever witnessed before, as the dancers were squat down, with their bodies almost to the ground, in a severe and most difficult posture, as will have been seen in the drawing" (Letters and Notes, vol. 2, pp. 120-27, pl. 227).

Sketched near Fort Gibson in 1834. The scene is repeated in cartoon 161.

In the Smithsonian Catlin collection is a Sauk and Fox or Iowa dance scene in which each Indian holds an eagle feather and wears another in his headdress. Their bodies are not painted white, however, nor is the position and arrangement of the dancers at all similar to number (this scene).