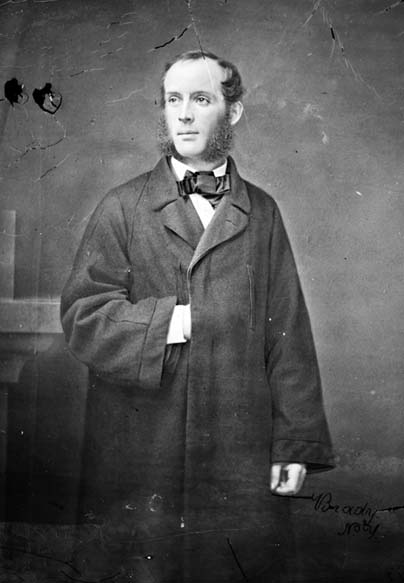

American Hudson River School Painter

1826 - 1900

American artists of the mid-nineteenth century usually went to Europe or the western frontier in order to expand their repertoire. Frederic Church went first to the tropics and volcanoes of South America. His reasons make a fascinating chapter in the history of American art and thought.

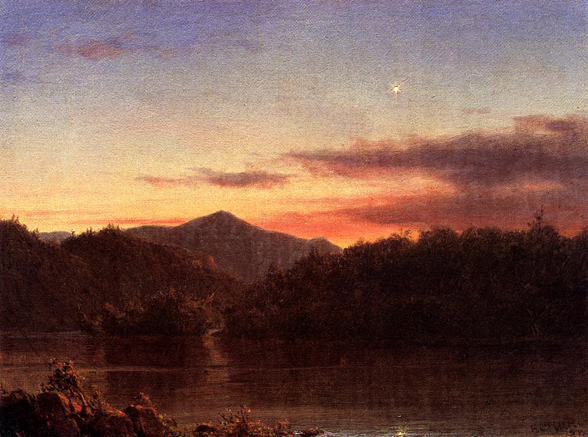

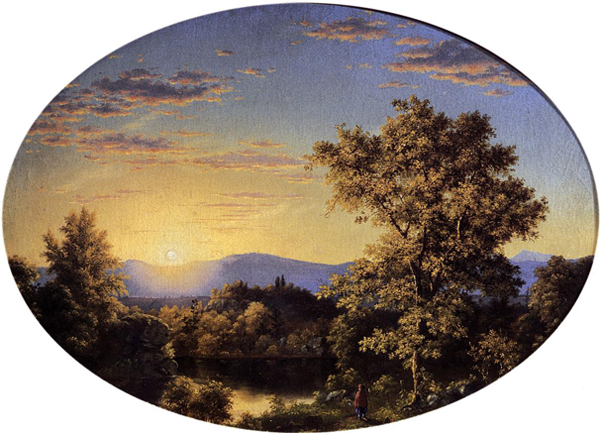

Church was the best known pupil of Thomas Cole, who recognized the singularity of American wilderness landscape and was the first to invest it with heroic grandeur. Church, like other painters of his generation, John Kensett, Sanford R. Gifford, and Jasper Cropsey, sketched and painted the Catskills and mountains of New England. In his early pictures he gave to water a reflective, burnished surface, to sunset clouds dramatic color and substance, and painted distant detail so clearly that his picture space seems filled with transparent radiance. By the early 1850's, Church was not only painting views of specific American places with topographical exactitude, he was also combining separate elements of meticulously detailed scenery into landscapes of heroic breadth and depth.

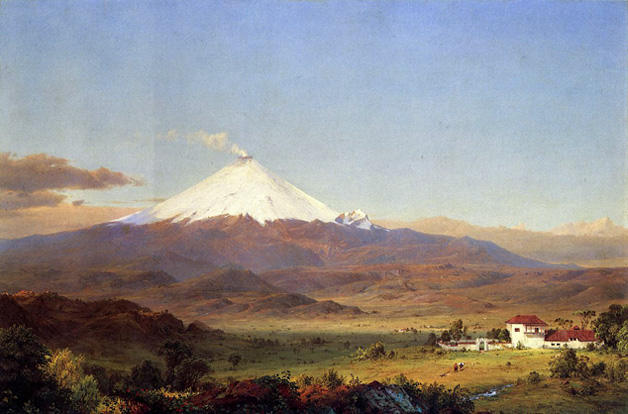

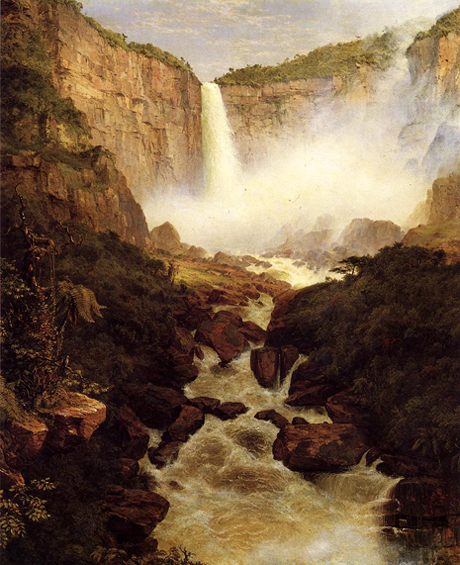

Church was inspired by the fascinating variety and complexity of nature as extolled by John Ruskin, the English writer, critic, and champion of J. M. W. Turner. Church also believed, like his contemporaries, that close study of nature was essential to grasp unique underlying truths which had moral implications. Thus, he was very impressed by the writings of the German naturalist, Alexander von Humboldt, whose influential Cosmos: Sketch of a Physical Description of the Universe first appeared in English in 1849. Von Humboldt's goal was to synthesize existing scientific knowledge into a theoretical system proving that nature was one great whole animated by internal forces which tended towards harmonious unity. He sought to prove that behind the complexity of the natural world was a divine order and he recognized the importance of landscape art in revealing this order. Von Humboldt specifically encouraged landscape painters to travel to those parts of the world having the greatest botanical and geological variety. Von Humboldt, who had set off for the tropics of South America in 1799, so inspired Church that in 1853 he retraced Humboldt's 1802 route from Barranquilla, in what is now Colombia, to Guayaquil, Ecuador, through the northern Andes where he made sketches of rivers, waterfalls, and volcanoes. One result was The Andes of Ecuador 1855, Church's largest painting to date. Seen from a lofty viewpoint, amid rich, tropical vegetation, a river tumbles into a lake which empties into a deep, misty gorge. The gorge leads into the distance and range after range of mountains suffused with a sunlit haze. The depth and breadth are so vast that it may be more accurately called, rather than landscape, earthscape.

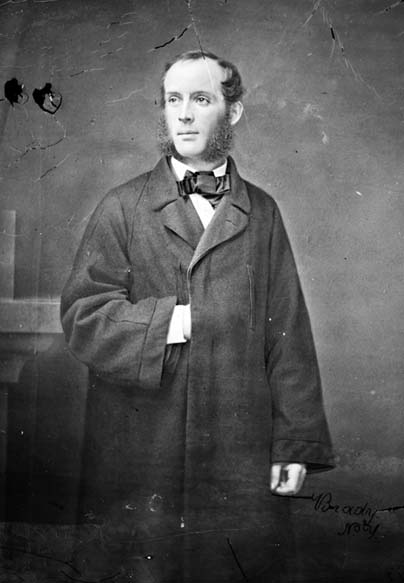

With his reputation firmly established by such tropical scenes, Church returned to the tropics in 1857 accompanied by Charles Remy Mignot (1831-1870), a fellow landscape painter from the United States. He landed this time on the coast of Ecuador at Guayaquil and pushed east into the interior to sketch the volcanoes Chimborazo, Cotopaxi, and Sangay.

In this panoramic view, Church combined scientific exploration and artistic license (altering the shape of the volcano and the terrain surrounding it) to create a symbolic and evocative portrayal of the vast New World. The artist produced at least 10 finished paintings of the dramatic volcanic mountain. He was inspired by the writings of German natural historian Alexander von Humboldt, who interpreted the wonders of the natural world as evidence of God's role as Creator.

Church's paintings, such as Cotopaxi, have been linked as well to the idea of "Manifest Destiny," a term used during this period by those Americans who not only wished to extend the boundaries of the United States to include Western territories but also favored intervention in the affairs of South America.

By January, 1858, he had begun his most ambitious, complex, and largest tropical scene, Heart of the Andes, 1858. Technically brilliant in its detailed rendering of an immensely wide and deep vista, the painting was seen on payment of twenty-five cents by more than twelve thousand people during three weeks in Church's New York studio. The artist brought together into one scene a tropical river flanked by lush dense vegetation, upland plains, and towering mountains, snowcapped at their highest elevation-geographically and climatically more than one region could possibly contain-dazzling in grandeur and mesmerizing in detail.

In 1859, however, Charles Darwin's The Origin of Species turned on its head Humboldt's concept that nature evolved toward harmony as the result of a guiding divine force. According to Darwin the state of nature was competition and struggle, not harmony. Thus was shattered a basic American concept of nature and landscape painting, namely, that man could turn to nature for moral guidance. By the late 1870's, the very ability to detail miles of scenery had become less admired than the creation of poetic visions.

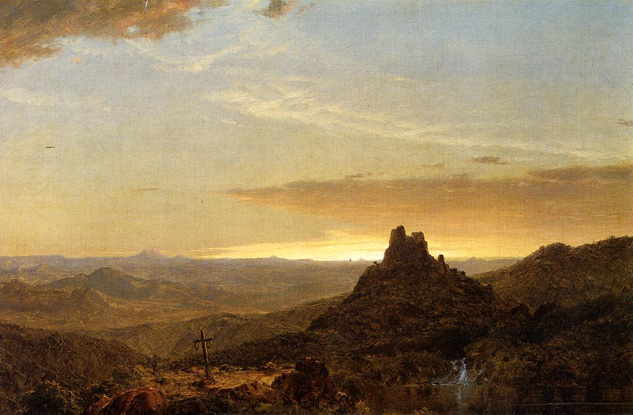

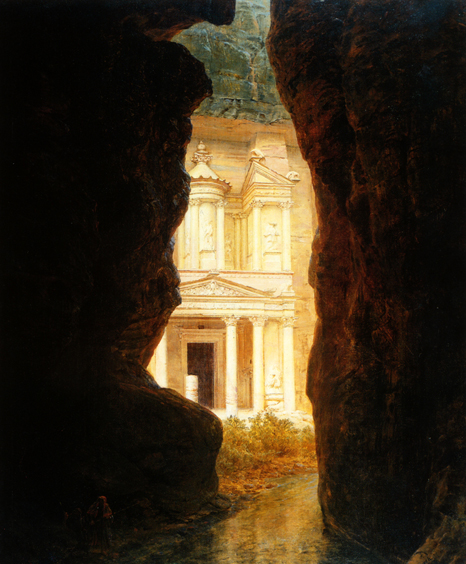

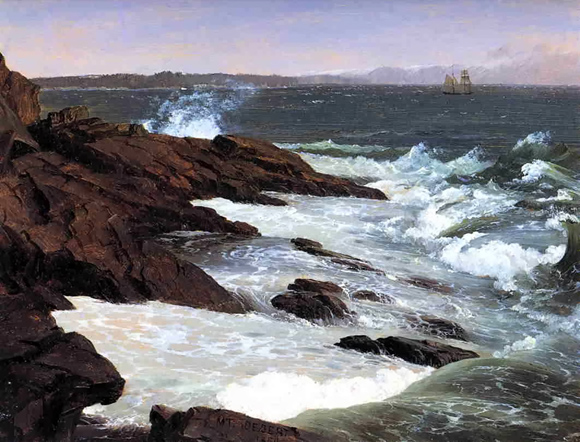

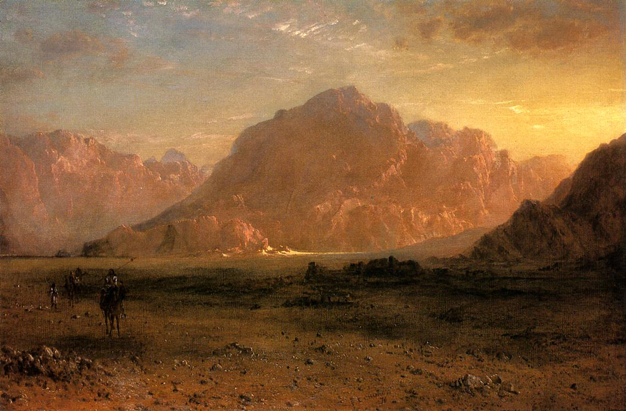

In the 1860's and early 1870's, Church turned away from the crystal clear, meticulously detailed views of vast expanses of the tropics in favor of sunlit landscapes of America, icebergs of the far North, and the coast of Maine. In 1867 he made his first trip to Europe and visited the Middle East, which provided exotic subjects for paintings of the Old World. When he did paint scenes of the tropics in the 1870's, they were quite different in both style and mood, as we see in the Butler Institutes In the Andes of 1878.

The left foreground suggests the generally rich abundance of tropical flora, while the two palm trees convey individual and specific natural histories. This we would expect from Church, but the shadowed foothills and distant violet-gray mountains separated by a layer of yellow cloud and a hazy atmosphere which blurs distant detail reveals a new and different vision. The scope of this view is expansive, but great distance is implied rather than described, and we must draw on our imagination to complete the landscape. In the absence of a single mountain protagonist the wake of a riverboat catches our attention. We feel linked to this human element, which is not lost in a superabundance of botanical and geological detail as in earlier pictures. Light has now become a major concern, and we look into a sun whose dazzle unifies the water of the river, the distant mountains, and the sky into a shimmering whole. The painting has a quiet rather than an epic mood. The setting is exotic, but the mood is pensive. Darwin had injected randomness into nature, hitherto seen as tending toward unity. Church, at the end of his active painting career, like many American painters in the last decades of the nineteenth century, sought through light a poetic unity in place of a scientific one based on a painstaking detailing of the physical world.

From: FREDERIC EDWIN CHURCH 1826-1900

Frederic Edwin Church was an American landscape painter born in Hartford, Connecticut. He was a central figure in the Hudson River School of American landscape painters. While committed to the natural sciences, he was "always concerned with including a spiritual dimension in his works".

The family wealth came from Church's father, Joseph Church, a silversmith and watchmaker in Hartford, Connecticut. (Joseph subsequently also became an official and a director of The Aetna Life Insurance Company) Joseph, in turn, was the son of Samuel Church, who founded the first paper mill in Lee, Massachusetts in the Berkshires, and this allowed him (Frederic) to pursue his interest in art from a very early age. At eighteen years of age, Church became the pupil of Thomas Cole in Catskill, New York after Daniel Wadsworth, a family neighbor and founder of the Wadsworth Atheneum, introduced the two. In May 1848, Church was elected as the youngest Associate of the National Academy of Design and was promoted to Academician the following year. Soon after, he sold his first major work to Hartford's Wadsworth Atheneum.

Church settled in New York where he taught his first pupil, William James Stillman. From the spring to autumn each year Church would travel, often by foot, sketching. He returned each winter to paint and to sell his work.

Between 1853 and 1857, Church traveled in South America, financed by businessman Cyrus West Field, who wished to use Church's paintings to lure investors to his South American ventures. Church was inspired by the Prussian explorer Alexander von Humboldt's Cosmos and his exploration of the continent; Humboldt had challenged artists to portray the "physiognomy" of the Andes.

Two years after returning to America, Church painted The Heart of the Andes (1859), now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, at the Tenth Street Studio in New York City. It is more than five feet high and nearly ten feet in length. Church unveiled the painting to an astonished public in New York City in 1859. The painting's frame had drawn curtains fitted to it, creating the illusion of a view out a window. The audience sat on benches to view the piece and Church strategically darkened the room, but spotlighted the landscape painting. Church also brought plants from a past trip to South America to heighten the viewers' experience. The public were charged admission and provided with opera glasses to examine the painting's details. The work was an instant success. Church eventually sold it for $10,000, at that time the highest price ever paid for a work by a living American artist.

Church showed his paintings at the annual exhibitions of the National Academy of Design, the American Art Union, and at the Boston Art Club, alongside Thomas Cole, Asher Brown Durand, John F. Kensett, and Jasper F. Cropsey. Critics and collectors appreciated the new art of landscape on display, and its progenitors came to be called the Hudson River School.

In 1860 Church bought a farm in Hudson, New York and married Isabel Carnes. Both Church's first son and daughter died in March, 1865 of diphtheria, but he and his wife started a new family with the birth of Frederic Joseph in 1866. When he and his wife had a family of four children, they began to travel together. In 1867 they visited Europe and the Middle East, allowing Church to return to painting larger works.

Before leaving on that trip, Church purchased the eighteen acres on the hilltop above his Hudson farm-land he had long wanted because of its magnificent views of the Hudson River and the Catskills. In 1870 he began the construction of a Persian-inspired mansion on the hilltop and the family moved into the home in the summer of 1872. Richard Morris Hunt was the architect for Cosy Cottage at Olana, and was consulted early on in the plans for the mansion, but after the Church's trip to Europe and what is now Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, Syria, Jordan and Egypt, the English architect Calvert Vaux was hired to complete the project. Church was deeply involved in the process, even completing his own architectural sketches for its design. This highly personal and eclectic castle incorporated many of the design ideas that he had acquired during his travels.

Olana State Historic Site is now owned and operated by the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation, Taconic Region and receives extensive support from The Olana Partnership, a private, non-profit organization.

The main house is open to the public for guided tours. A visitor center offers a film and panel exhibit as well as a Museum Shop, operated by The Olana Partnership, offering books and many items inspired by the exotic locales of Church's travels and paintings. The grounds are open year-round, 8am-sunset, for hiking, picnicking, snowshoeing or just enjoying the view.

From: Wikipedia

_1882.jpg)

_1877.jpg)

El Rio de Luz (The River of Light) is a fanciful pastiche based on numerous sketches and notations that Church had made during an 1857 trip to South America. Despite the time-lapse of twenty years, the tightly focused realism, the overall tonal harmony and restrained coloration, and the compositional unity all lend a remarkable cohesiveness to the work. Church rendered the verdant foliage with exquisite attention to detail, and his virtuoso treatment of tropical sunlight diffused by morning mist makes the atmosphere seem tangible. Red-breasted hummingbirds, a flock of waterfowl, and a distant canoeist occupy the scene, but they do not disturb the overall mood of tranquility. Confronted with the glowing light and heavy vapors of this raw landscape, the viewer is invited to liken daybreak in the tropical rainforest to the dawn of creation itself.

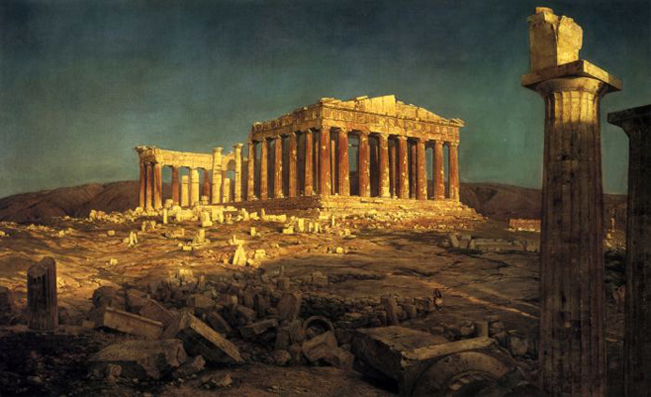

Church maintained that Jerusalem was the best picture he ever painted. When the painting was given a solo showing at Goupil's Gallery in New York in 1871, spectators flocked to see it, often forming six rows of people at a time and using opera glasses to see the astonishing details more clearly. Church published a pictorial key so that the painting's admirers could locate sacred sites as well as appreciate Jerusalem's accuracy.

In 1844, Church was the first formal pupil accepted by Thomas Cole, America's leading landscape painter. From Cole, Church learned both a reverence for nature as a subject and a commitment to making his art express noble and lofty ideas. Church made his professional debut at the National Academy of Design in 1845. By 1848, when Morning and three other of his works were exhibited at the American Art-Union, he had already gained a significant reputation.

The image was inspired by a sunrise Church saw during the first weeks of the Civil War. It is significant that Church does not depict a physical flag but one that appears as a wondrous apparition in the sky. Church's manipulation of the sky suggests that the Union has God and nature on its side and that the Union is in harmony with the natural order of things. The symbolism of the image is potent and patriotic. Church's flag appears torn but vibrant, suggesting the enduring strength of the Union. He was a strong believer in the Union cause and was undoubtedly pleased when the image was used as the basis for a lithograph made for wide distribution.

_1869.jpg)

Church's interest in South American scenery was inspired by the writings of Alexander von Humboldt, a German naturalist. During his travels to South America, Humboldt was struck by the tremendous range of climates in Ecuador: icy mountaintops, grassy plains, and steamy jungles. Humboldt saw this diversity as evidence of the divine presence in the creation of the world. South America was a kind of Garden of Eden to which all other climates of the world -- and thus life itself -- could be linked.

Church was rigorous in his attempts to achieve truth to nature. The foreground is wet and glistening because it has risen from under the water; the changing level of the sea has left horizontal stains on the main iceberg. The brilliant blue veins in the iceberg are caused by water frozen in the cracks of a glacier.

Perhaps the artist intended twilight to suggest the end of a cosmic cycle---a meaning that coincides with the feeling that the Civil War (imminent in 1860 when this picture was made) would change American civilization forever. The panoramic splendor created by brilliant clouds floating above a tranquil landscape also suggests the divine authority of "manifest destiny," the idea that Americans of European stock had a right to the continent. Seen by large numbers of Americans in a touring exhibition organized by Church himself, this picture was marketed as essentially "American"---a comforting, patriotic image of the American wilderness.

Source: Art Renewal Center

Source: Frederic Edwin Church Online

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.