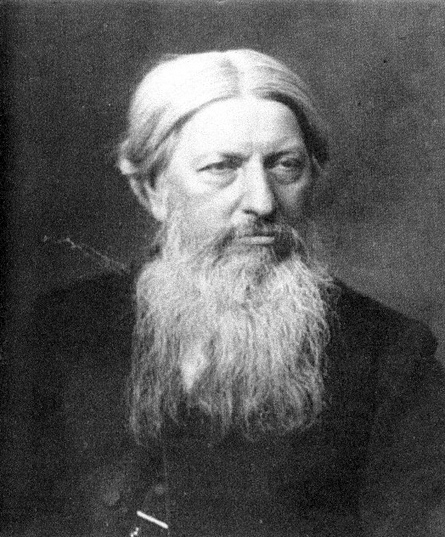

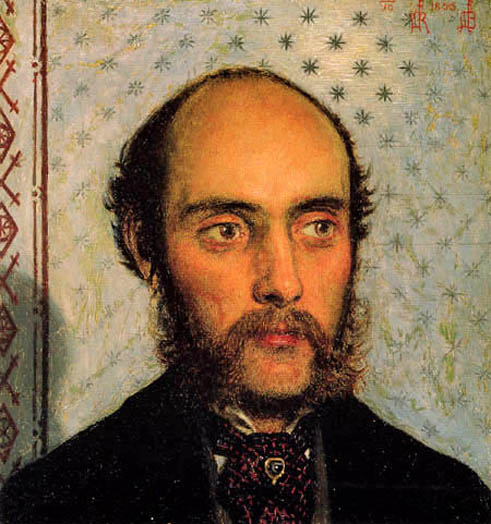

1821 - 1893

Self Portrait: 1877

The Last of England: 1852-55

This is a painting about emigration, the couple are departing for Australia. The subject itself - departure in desperate circumstances for a foreign land - has parallels with the biblical story of the Flight into Egypt. The artist himself posed for the painting, along with his partner Emma, and their children Cathy, the fair-haired girl in the background, and Oliver, the baby.

Work

The subject, of work in all its forms, was inspired by Brown seeing navvies at work laying drains. Each character or group is of symbolic significance, from the navvies representing physical work to the gentleman and his daughter on horseback who are rich enough not to have to work. The young lady giving out religious tracts is doing 'God's work', while the itinerant farm workers fall asleep under the trees are destitute for the want of work. The two gentlemen on the right were described by the artist as the 'brainworkers' who seem to be idle, but they are the source of social reform and prosperity. The potboy with his beer tray carries a copy of 'The Times' under his arm. Literacy was seen as the key to social improvement and political power for the working class. The Masonic symbols of trowel and set-square in the foreground represent another means of advancement for tradesmen.

Manchester Murals

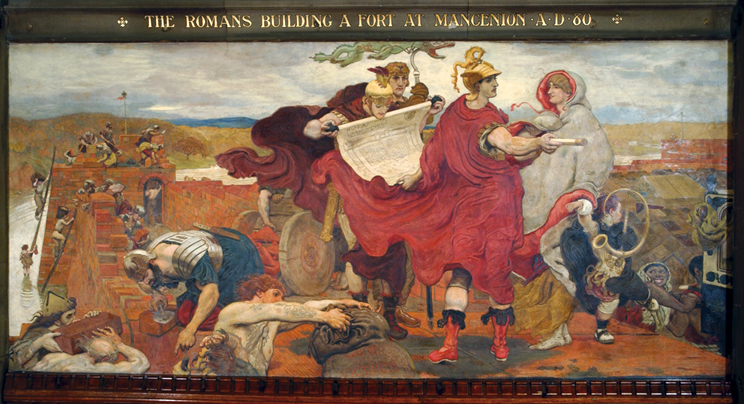

Manchester Mural: Romans

The Romans Building a Fort at Mancenion

The mural depicts the building of a Roman fort by enslaved Britons while a Roman general gives the orders. The fort, now known as Mamucium, was at what is now the area of Castlefield, near the centre of Manchester.

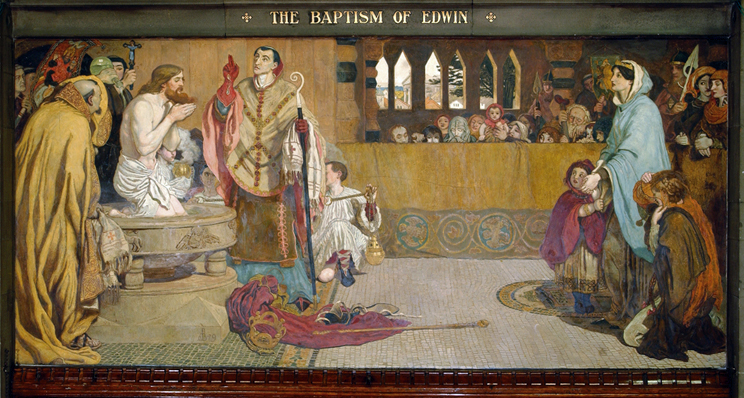

Manchester Mural: Edwin

The Baptism of Edwin

The mural depicts the Baptism of Edwin of Northumbria, who was also King of Deira which included the region where Manchester is located, at York, watched by his Christian wife Ethelburga and family.

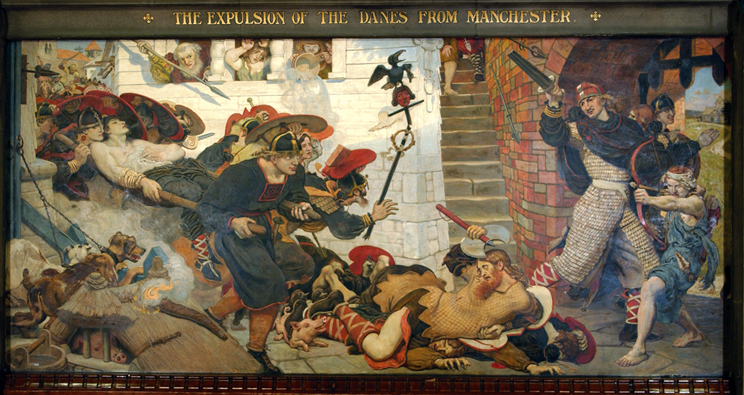

Manchester Mural: Danes

The Expulsion of the Danes from Manchester

The mural depicts the retreat of the Danes from Manchester - showing soldiers carrying their general on a stretcher.

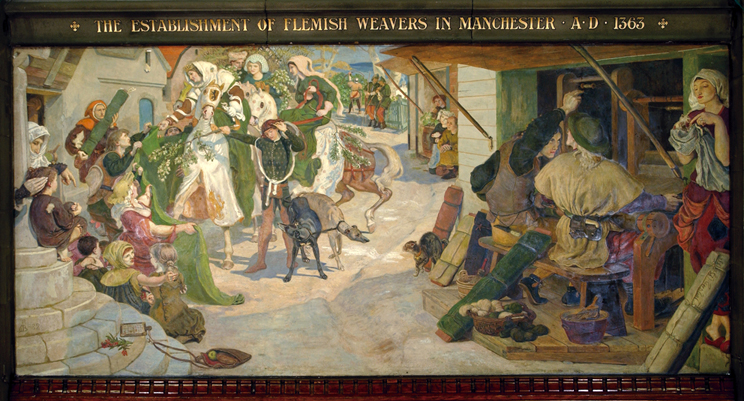

Manchester Mural: Flemish

The Establishment of Flemish Weavers in Manchester A.D. 1363

Queen Philippa of Hainault greets Flemish weavers who were invited to England under Edward III of England's act of 1337.

Manchester Mural: Wycliffe

The Trial of Wycliffe A.D. 1377

John Wycliffe is depicted on trial, defended by his patron, John of Gaunt. Geoffrey Chaucer, another protegé of Gaunt's, acts as recorder.

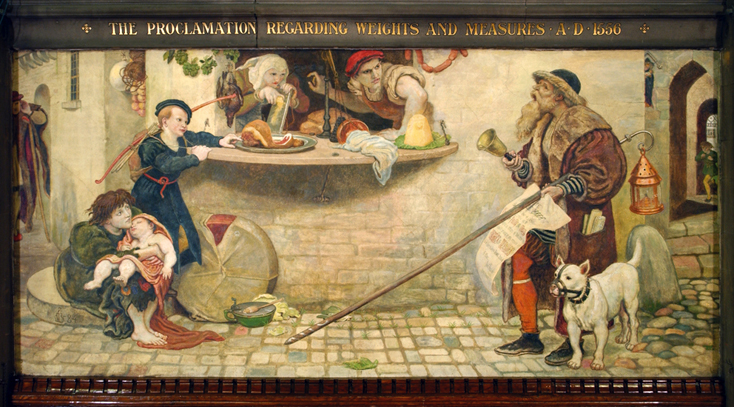

Manchester Mural: Proclamation

The Proclamation regarding Weights and Measures A.D. 1556

In 1556, Manchester's Court passed an edict directing that "The Burgess and others of the Town of Manchester shall send in all manner of Weights and Measures to be tried by their Majesties standard."

Manchester Mural: Crabtree

Crabtree watching the Transit of Venus A.D. 1639

William Crabtree, a draper who lived at Broughton, was asked by a curate friend, Jeremiah Horrocks, to observe the Transit of Venus, on 24 November 1639. Crabtree's diligence and rigor enabled him to correct Horrocks' faulty calculations and to observe the transit on 4 December.

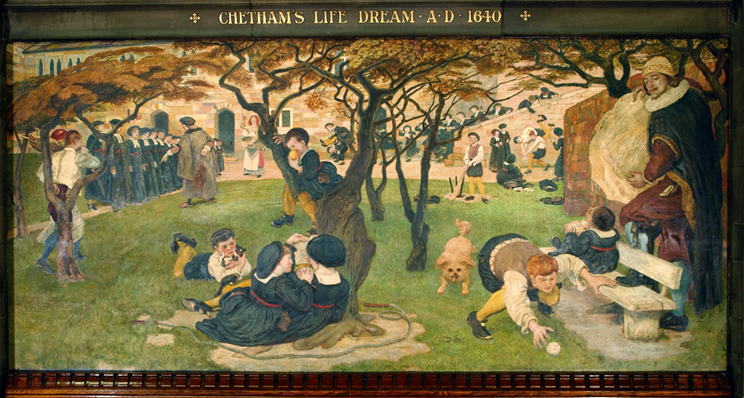

Manchester Mural: Chetham

Chetham's Life's Dream A.D. 1640

The mural depicts merchant philanthropist Humphrey Chetham's dream of the school, Chetham's School of Music, which was to be established with his legacy. Chetham is portrayed studying his will to the right of the painting.

Manchester Mural: Bradshaw

Bradshaw's Defense of Manchester A.D. 1642

During the English Civil War, Manchester was laid under siege by Royalist troops under the command of Lord Strange. It was, however, John Rosworm, not John Bradshaw as depicted, who defended the town.

This was the last of the paintings to be completed. It is not strictly a mural, since Brown was by this time too frail to work in the hall itself. It was painted on canvas and adhered to the wall.

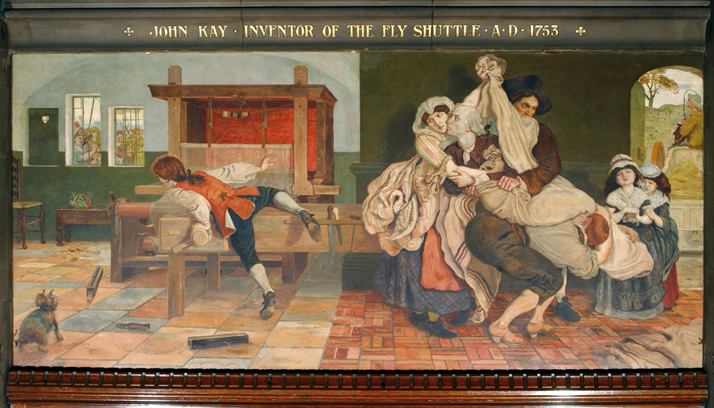

Manchester Mural: John Kay

John Kay, Inventor of the Fly Shuttle A.D. 1753

The invention, by John Kay, of the flying shuttle revolutionized weaving. The mural depicts rioters, who feared their jobs were in danger, breaking in to destroy the loom, while Kay is being smuggled to safety.

Manchester Mural: Bridgewater

The Opening of the Bridgewater Canal A.D. 1761

The 3rd Earl of Bridgewater owned coal mines in Worsley , and collaborated with engineer James Brindley to build the Bridgewater Canal to carry coal into the heart of Manchester.

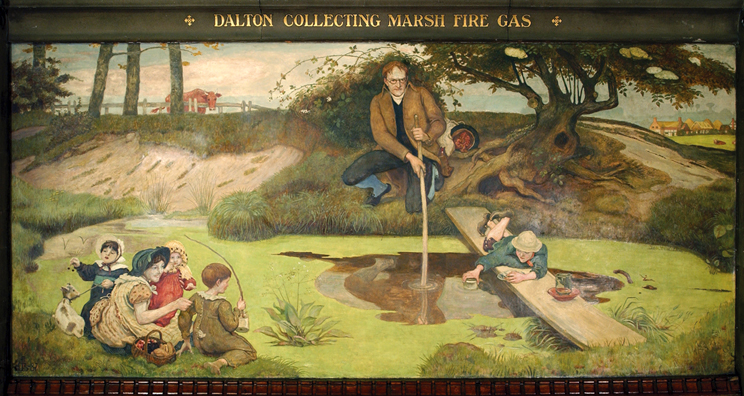

Manchester Mural: Dalton

Dalton collecting Marsh-Fire Gas

The mural depicts the scientist John Dalton collecting gases. His studies led to the development of atomic theory.

Elizabeth Bromley Brown

In 1841 Brown married Elizabeth Bromley and the couple relocated to Paris where he spent time learning the Spanish masters along with contemporary artists.

The Bromley Children

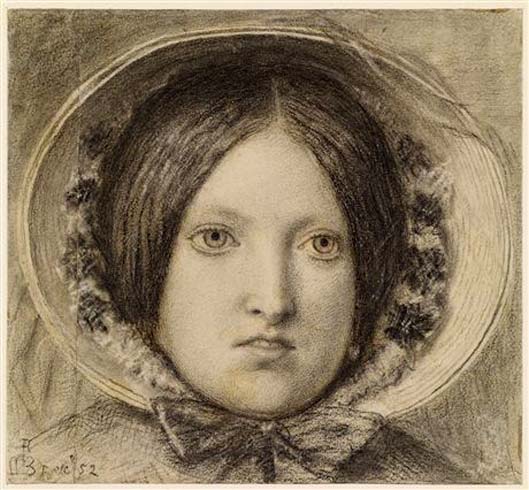

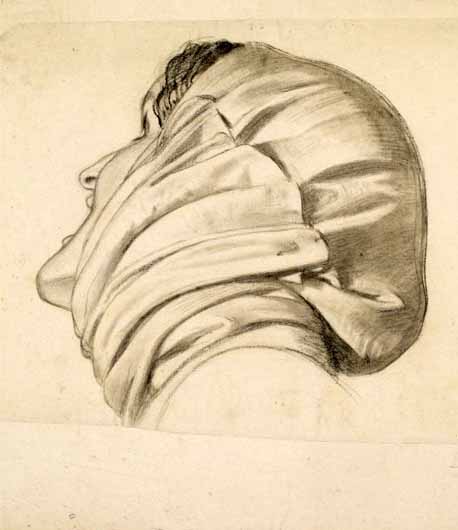

Emma Hill: 1852

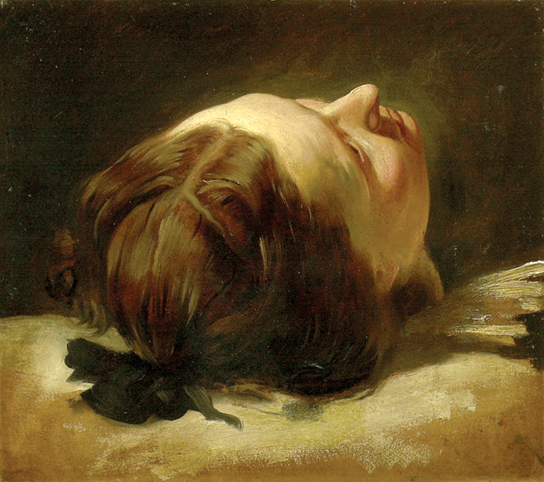

Emma Hill became Madox Brown's second wife in 1853. This portrait of her was made around Christmas in 1848. It is possibly the earliest drawing of Emma and was made soon after Brown hired her as his model. As Theresa Newman and Ray Watkinson have discovered she seems to have been using her mother's maiden name at the time, following the death of her father, and in his diary Brown refers to her as Miss Stone.

Although this is a portrait of Emma it also appears to be a head study for Brown's painting 'Lear and Cordelia' (1848-49, oil on canvas, Tate, London). On 13 January 1849 Brown first mentions 'Miss Stone' in his diary as the model sitting for Cordelia: '13th Miss Stone, began a drawing for the head of Cordelia'. The angle of the head, the downward gaze and the hairstyle are the same as in the painting. Only the slightly open mouth is different but this appears to have recorded a particular facial feature of Emma's, many of Brown's portraits of her show that her top lip naturally curled up to reveal her teeth. It is also possible that arm and hand studies for Lear and Cordelia may have been drawn from Emma.

While one is preparing a page such as this, you are constantly reminded of our 'Shared Humanity' with those who have come before us and those who will come after us. It is far too easy to praise ourselves for the 'Enlightened Tolerance' our Humanity has achieved in the Twenty-First Century as we criticize the 'Narrow Intolerance' of Nineteenth Century Victorians. I believe that we possess the possibility of 'Enlightenment' but for reasons that are still not clear to me we seem to follow the path of 'Intolerant Bigotry'. The Victorians lived during an age that was noted for its 'Gender Inequality' which we have yet to completely overcome to this very day.

As I was surfing through the net searching for more background about Ford Madox Brown, I discovered an article about him that intrigued me: 'The Secret Love of Ford Madox Brown'. It is not that I am trying to excuse bad behavior by anyone, but wonder what prevents us from seeing the humane in humanity as well as not understanding the distinction between 'Compassion' and 'Intolerance'.

Senex Magister

The Secret Love of Ford Madox Brown

The King of the Pre-Raphaelites and his Relationship with the Feminist, Shelley-worshipping Mathilde Blind

Admirers thought Madox Brown the handsomest man in London and the best conversationalist. Though he was never formally a member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, his art had been so closely associated with theirs that he was sometimes called King of the Pre-Raphaelites. During his party days he was known as a King of Hearts. The most masculine of men, his life was shaped by the sympathy - and complexities - of four women central to it: his two secret loves, the artist Marie Spartali and the author Mathilde Blind, and his two wives and models, Elizabeth Bromley and Emma Hill. All of them exploded any conventional notions about the artist's silent muse. In a sense, with their distinct talents and opinions, they represented a route towards modernity that made a sharp impact on Madox Brown's whole oeuvre, from intense private pictures to spectacular public art. He kept his beard and hair long, and his second wife Emma cut it blunt and square so that he looked like the playing card king. But as he aged, he cultivated a King Lear-like appearance. Shakespeare's tragedy had engaged him throughout his career: as a young man in Paris in the 1840's he made a series of powerful drawings to illustrate it. He loved the stage, especially Shakespeare, and blocked his pictures with the instincts of a theatre director.

Marie Spartali Stillman: 1868

.jpg)

Mathilde Blind

One day, two years after the death of his first wife in 1846, "a girl as loves me came in and disturbed me". With un-Victorian directness Emma Hill simply walked into Madox Brown's life - and his art. There was a recurrence of the artist's involvement with King Lear when he made his first extant portrait of Emma, a delicate profile head, dated Christmas 1848, a preliminary study for his painting "Cordelia at the Bedside of Lear". With its ideal regularity, Emma's face could become a princess's but also represent Everywoman - as the emigrant wife in "The Last of England". Emma was no longer the uneducated girl she had been when she and Madox Brown first met. But she could never match the intellectual rapport that Mathilde Blind, another of their party guests, could offer him.

Emma Hill: ca 1848

Emma Hill became Madox Brown's second wife in 1853. This portrait of her was made around Christmas in 1848. It is possibly the earliest drawing of Emma and was made soon after Brown hired her as his model. As Theresa Newman and Ray Watkinson have discovered she seems to have been using her mother's maiden name at the time, following the death of her father, and in his diary Brown refers to her as Miss Stone.

Although this is a portrait of Emma it also appears to be a head study for Brown's painting 'Lear and Cordelia' (1848-49, oil on canvas, Tate, London). On 13 January 1849 Brown first mentions 'Miss Stone' in his diary as the model sitting for Cordelia: '13th Miss Stone, began a drawing for the head of Cordelia'. The angle of the head, the downward gaze and the hairstyle are the same as in the painting. Only the slightly open mouth is different but this appears to have recorded a particular facial feature of Emma's, many of Brown's portraits of her show that her top lip naturally curled up to reveal her teeth. It is also possible that arm and hand studies for Lear and Cordelia may have been drawn from Emma.

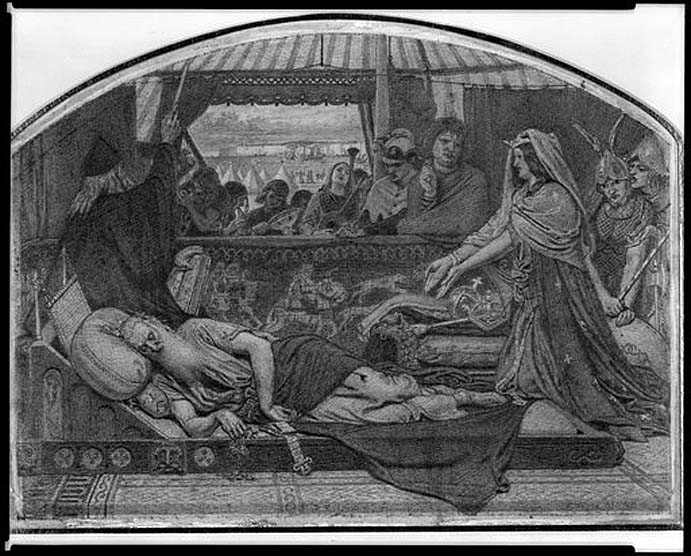

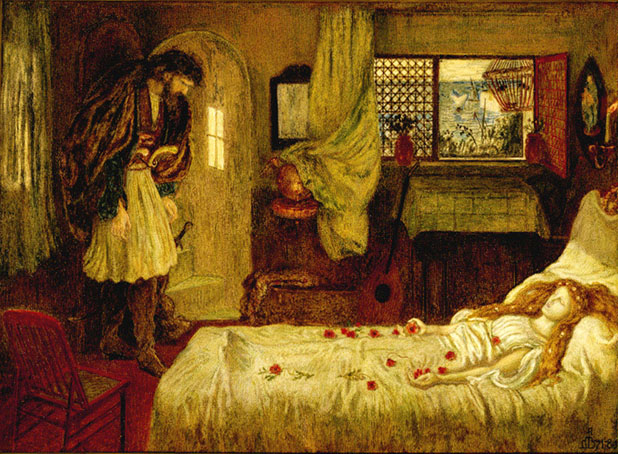

Cordelia at the Bedside of Lear

Lear and Cordelia 1849-54

This is one of three paintings by Ford Madox Brown illustrating Shakespeare's play King Lear. This scene shows Lear with his youngest daughter, Cordelia, on the right. Lear's doctor orders the musicians to play more loudly and awaken him. But Cordelia is anxious that her ailing father should sleep and she speaks the lament inscribed on the painting's frame. In the play Lear divides his kingdom between his other two daughters and their husbands. But, after a painful period of self-discovery, he realizes that Cordelia is his only true loving child.

Lear and Cordelia: 1849-54

Mathilde Blind, née Cohen, a young German-Jewish writer, committed feminist and agnostic, published her Poems in 1867, under the androgynous pseudonym of Claude Lake. She arrived in England, aged eleven, in 1852 as an asylum seeker, along with her mother, Friederike Cohen, and her (Protestant) stepfather, Karl Blind, a leader of German Revolution in 1848. The Blinds' home near Swiss Cottage became a focus for Continental exiles. Marx had been an early associate, Mazzini a frequent visitor and Mathilde's special hero. In 1866, Mathilde's brother, Ferdinand, shot but failed to assassinate Bismarck, killing himself in despair at the police station. Mathilde came from an unconventional European background of rational freethinking and practical action. She had radical credentials.

Her education had been an academically distinguished one, in Germany, Belgium and England. But it was her passion for Shelley which linked her to Pre-Raphaelite circles in bohemian London. After losing his beloved art student, Marie Spartali, to marriage in 1871, Madox Brown lamented that "everyone was somewhere else". Within weeks he chose Lynmouth, the Devon resort with Shelley connections, for his summer holiday and invited Mathilde to join the family. Petite, dark and intense in vivid striped silks, Mathilde whirled in on them with a storm of talk and German argument, driven by a literary quest. She tracked down an old woman, Mary Blackmore, who remembered Shelley. "I am going to draw her", wrote Madox Brown, and "Miss Blind is to make an article about her." Artist and poet were drawn together in the excitement of a shared project.

In her late twenties, twelve years younger than Brown's corn-blonde wife Emma, and twenty years junior to the artist, Mathilde was mesmerizing. For Richard Garnett, superintendent of the British Museum Reading Room, she was "one of the most magnetic young women in London" and he fell in love with her. Joaquin Miller, an American poet and adventurer, proposed to her, and it was rumored that even Swinburne might marry her. Mathilde had many friends and admirers - of both sexes - but she gravitated towards married men: Garnett, William Michael Rossetti, and, most enduringly and passionately, Ford Madox Brown. From now on, she lived intermittently but persistently in the Madox Browns' London home.

In September 1877, Manchester's new Town Hall, designed by Alfred Waterhouse, received its ceremonial opening. However, it lacked the historical murals envisaged by the architect for its Great Hall. The councilors were nervous about appointing Madox Brown, whose paintings were simply "too outré" for them. A Manchester city councilor, Charles Rowley, explained that his art was "not pitched in a key popular enough for most of us but I think we could get him to compromise a little in that line". Compromise was not an element in Madox Brown's personality, but by 1878 mediation brought him the commission. He and Emma moved to Manchester in 1880 - where Mathilde soon joined them. The ménage à trois was no more tenable in the North than it had proved to be in London, so Mathilde moved out to nearby lodgings. This was a pattern repeated, with variations, throughout their friendship.

As the Madox Browns and Mathilde tried to acclimatize to "cold and boisterous" Manchester, they all teetered on the tightrope of their awkward threesome. Mathilde and Madox Brown were recovering from overwork and ill health. Emma was often unwell. The painter was working punishing days at Manchester Town Hall, "10 a.m. to 10 p.m. and 7 days per week - consequently no dinner, or little trips to friends". At the same time, Mathilde was reading Shelley and Darwin, and researching for her biographies of George Eliot and Madame Roland, "transgressive" female subjects who reflected her personal philosophy. In a similar way, although the murals were, on the face of it, a visual history for the people of Manchester to read, a modern equivalent to the Bayeux Tapestry, they provided an opportunity for the artist to embed his own values in them.

George Eliot at 30, Painted

by Francois D'Albert Durade

Portrait of Madame Roland

by Adelaide Labille-Guiard: 1787

One of the most dramatic panels was "The Trial of Wycliffe". Madox Brown, by now a confirmed agnostic, if not an atheist, nevertheless recognized the power of religious subjects in art. The Nonconformist figure of Wycliffe sorted well with the post-Darwinian, secular philosophy Madox Brown shared with Mathilde. Her poem "The Prophecy of Saint Oran" was so shocking in its challenge to conventional Christianity that the publisher, Newman and Co, took fright and withdrew it from circulation because of its "atheistic character". Oran was one of Columba's most devoted monks but "his pulses thrilled" with love for Mona, a beautiful pagan. He tries to convert her to Christianity but she simply cannot understand "his joy-killing creed", nor fathom "of what she should repent". Oran fights to keep faith with chastity, until neither he nor Mona can restrain their love:

"What boots it thus to struggle with his sin,

So much more sweet than all his virtues were?

Like a great flood let all her love roll in

And his soul stifle mid her golden hair!

And so he barters his eternal bliss

For the divine delirium of her kiss!"

As they labor to build God's holy house on Iona, Columba's monks are thwarted by violent storms, and local people revert to their pagan gods. Suspecting a curse on their work, Columba asks "what man among you all / Living in deadly sin, yet wears the mask / Of sanctity?". Oran denies his sin but is flushed out by the arrival of Mona, like the ghost of a Druid princess, wildly searching for her lover. Columba sentences Oran to be buried alive. Three days later, Oran's bloodless face breaks out of the clay and speaks: "Lo, I come back from the grave, - / Behold, there is no God to smite or save". He reports there is no devil, no heaven, no hell. Instead, he tells them, "Ye can have Eden here! . . . Cast down the crucifix, take up the plough!". There is indeed a God: "that God is Love", the "tender human tie" that Oran knows with Mona. Although Columba orders his instant re-burial, Oran's voice is stronger and reverberates after the grave is shut and the poem ended.

Study of a Monk Representing the Catholic Faith: 1848

Cromwell on his Farm by Ford Madox Brown

The central figure in this painting is Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658). After his death Cromwell gained a highly negative reputation as a ruthless tyrant. It was not until the publication of Thomas Carlyle's 'The Letters and Speeches of Oliver Cromwell' in 1845 that this image of him began to change. Carlyle (1795-1881) was one of the most influential essayists and historians of the nineteenth century. He focused on Cromwell's positive achievements and portrayed him as a self-made man and a reformer of passionate moral conviction. Cromwell became the hero of the reformers, liberals and new men of nineteenth-century England.

Ford Madox Brown (1821-1893) was enormously impressed by Carlyle's books. In 1855 he referred enthusiastically to Carlyle as a 'glorious kind hearted old chap' and 'sage teacher.' From this time onwards the historian's name appears several times in Brown's diary and he included a portrait of him in 'Work' (1852-1863, Manchester City Art Gallery), one of his most important paintings. Brown read 'The Letters and Speeches of Oliver Cromwell' in the early 1850's when he was suffering from severe melancholy. Inspired by Carlyle's reassessment of Cromwell Brown began composing this painting in 1853. He first made a small watercolor of the subject (now in Manchester City Art Gallery) choosing to show Cromwell on his farm in Saint Ives in 1630 before the first Civil War when he too was suffering from low spirits. In fact, Brown so revered Cromwell that he named his first born son Oliver.

However, it was not until 1873 that William Brockbank, a Mancunian Pre-Raphaelite patron commissioned Brown to complete the picture for £400. Cromwell is shown sitting on his horse. In one hand he holds an oak sapling, symbolic of moral strength and his future power, and in the other he holds a Book of Common Prayer. In the distance behind him stands his wife and child while all around him farm activities are taking place. However, he is lost in a religious trance pondering over the Bible passages: 'Lord, how long? Wilt thou hide Thyself forever?' 'And shall thy wrath burn like fire?' after coming across a patch of burning stubble. He is oblivious to the noise around him including the maid shouting him for dinner, the squealing pigs and the large herd of cows behind him. Carlyle and Brown were both interested in exploring the lives of ordinary people in the past. For this reason Brown made sure to include farm workers and a domestic servant in the painting as well as the future Lord Protector.

Brown liked to research his paintings thoroughly. He used the latest sourcebooks to find the correct historical costumes and accessories. He even made a trip to Saint Ives using Carlyle's work as a guide book. In June 1873 he stayed with his close friend Dante Gabriel Rossetti in Kelmscott Manor, Oxfordshire. The countryside was similar to that around Saint Ives and allowed him to paint directly on to the canvas from nature. The artist designed the frame and included the two related Bible passages as part of the decoration. The painting was completed in a year and first shown at the Royal Manchester Institution in 1874 where it was enthusiastically received by the critics.

Mathilde's extraordinary poem could be read as a blasphemous reworking of the Resurrection or as an expression of nineteenth-century humanism. Madox Brown's Wycliffe and Mathilde Blind's Oran were both modernizing voices. Their bodies could be buried alive or burned - as Wycliffe's was after his death - but they could not be silenced. Artist and poet also shared democratic principles. Madox Brown's long identification with Oliver Cromwell was still apparent, after earlier works depicting Cromwell, in the final mural he made for Manchester, "Bradshaw's Defense of Manchester". It was a heroic subject, heroically undertaken after his painting hand was paralyzed by a stroke, in honor of his Cromwellian principles. Mathilde, too, championed democratic rights, particularly those of uprooted Highland crofters in her protest poem "The Heather on Fire".

By August 1882, Mathilde was exhausted. She had just finished her Biography of George Eliot. In the author, who also lived in an irregular union with a married man, Mathilde found a modern, literary heroine with special relevance to her own relationship with Madox Brown and their erotic ménage. But biography was not Mathilde's natural genre. It had been hard labor to corral facts in "luminous arrangement". At last she felt she could lay down her pen, "go out and actually stay out as long as ever I liked". Perhaps her independent wandering over the hills was partly the cause of a serious "tiff" between her and Madox Brown. For in spite of uplifting views from their holiday cottage at Chapel-en-le-Frith in Derbyshire, it was here that Mathilde and Madox Brown had a cantankerous falling-out.

They walked out on each other in turn, and the breach was still not healed by September when the Madox Browns returned to Manchester. The artist attempted to appease Mathilde's "soreness" by letter but Mathilde did not relent. "Stiff and unyielding", she regarded "their intimate friendship as at an end". William Rossetti found the stand-off "certainly very ungrateful and foolish on Mathilde's part, as Brown has for some years past made her practically a member of his family, housing and supporting her". What sort of family role did William, or other observers, consider Mathilde played in relation to Madox Brown? Two years senior to his eldest child, was she an "adopted" extra daughter, resented by Lucy and Cathy? Or was she a live-in competitor to Emma, a mistress in the head if not in the bed? It seems probable that she slipped between both roles at different times. The intensity of the row between Mathilde and Madox Brown betrayed the complexity of their emotional relationship.

Mathilde seized an opportunity to mend the quarrel some months later when Madox Brown fell seriously ill and, though warily and not immediately, she took the train to be at his side. But this time she stayed outside the family home. The artist recovered slowly, reporting that Emma and Mathilde "keep well on the whole". They had established a domestic truce and a diurnal rhythm. "Mathilde works in her lodgings all the early part of the day and walks here usually by 4 or 5 and then reads us what she may have done - or else poetry of some kind and we chat".

After the virtual completion of the Manchester Murals and Emma's death in 1890, Madox Brown was again living in London, with Mathilde close by. Contemporary speculation murmured that the two planned to marry - or had already married. In these years Madox Brown's mind was brought back to Shakespeare when Henry Irving commissioned him to design three majestic sets for his King Lear in 1892. Irving's Lear and Ellen Terry's Cordelia wore the same combination of "Roman-pagan-British" costumes that Madox Brown had shown in his earlier Lear pictures. Reviewers found the settings "gorgeous throughout". Mathilde saw the production and told Irving how "extraordinarily moved" she had been by his performance.

Henry Irving: 1883

by John Everett Millais

Dame (Alice) Ellen Terry

as Cordelia in King Lear

_Ellen_Terry_as_Cordelia_in_King_Lear.jpg)

On Sunday October 1, 1893, Ford Madox Brown worked for an hour or two on his replica of the Wycliffe cartoon. He felt inexplicably tired. As Cathy Hueffer, his widowed younger daughter, helped him upstairs to bed, he said to her, "Well, my dear, my work's done now". On Monday he stayed in bed, at his home hung with golden wallpaper at 1 Saint Edmund's Terrace, adjacent to Primrose Hill, in north London. Later Lucy Rossetti, his eldest daughter, visited for a painful farewell - wasted by tuberculosis, she was leaving the next day to winter in Italy. At this point, either Cathy or her son, the young Ford Madox Hueffer (Ford), decided to summon Mathilde back from her writing holiday at Wendover with Mona Caird. Lucy was implacably opposed to Mathilde's liaison with her father and no one wanted to take the risk of the two women colliding on the stairs. However, Cathy was less intransigent than her half-sister on the subject of Mathilde. Although his talent was for fiction rather than biography, Ford Madox Ford later maintained that his grandfather's "last quite coherent words" were spoken either to Lucy on the eve of her departure, or to Mathilde "while advising some alterations" to her work in progress. Madox Brown's partisanship of Mathilde's work had always fuelled their relationship. "He listened with his usual vivid sympathy", she said, "to some poems I had lately written" (while on holiday with Mona Caird). Mathilde's love poems were partly disguised autobiography, and fused her tumultuous feelings for various people and places.

Catherine (Madox Brown) Hueffer: 1869

_Hueffer_1869.jpg)

Her earliest memories were of modeling for her father as a babe in arms, and visits by the Rossetti brothers. She attended Queen's College and was trained in art by her father, Ford Madox Brown. She also worked as his model and studio assistant. Her first exhibition was in 1869 and thereafter chiefly painted in watercolors. In 1872 she married musicologist, Franz Hueffer. Her husband's death in 1889 left her in financial straits and she was denied a Civil List pension.

Ford Madox Brown at the Easel

by Catherine Madox Brown

Lucy Madox Brown: 1874

by Rossetti

Born in Paris 1843, she was the eldest of Ford Madox Brown's three surviving children. Lucy posed for her father from an early age and later acted as his secretary and studio assistant. She began painting herself in 1868 under the guidance of her father. Her first exhibit was in 1869 and during her career, she appeared largely as a watercolorist with figure compositions drawn from modern life, literature and history. In 1874 she married William Rossetti and had four children in the next seven years. After becoming a mother she painted little and from 1885 showed signs of respiratory disease. Radical in her political and cultural interests, she was a signatory of the national petition for women's suffrage and wrote an unpublished biography of her father.

Margaret Roper Rescuing the Head of her Father

by Lucy Madox Brown-Rossetti

No one wanted to believe the artist was on his deathbed: they were planning for the future. "At his express wish", Mathilde "went to Tunbridge Wells", one of her favorite health retreats, "to look for rooms for himself, Mrs. Hueffer, and her daughter (Juliet). The idea of going there seemed to please him greatly". However, on Tuesday, Madox Brown suffered an attack of apoplexy (stroke or cerebral event) and remained comatose for three days. Cathy called in Dr Gill of Russell Square and Dr Roberts of Harley Street. On the morning of Friday October 6, the seventy-two-year-old artist regained consciousness briefly, had breakfast, relapsed into a coma and died at 4.30 pm. Mathilde went into mourning, alone, in Tunbridge Wells, at one of the dozens of lodgings she used throughout her peripatetic life.

The funeral took place in the unconsecrated part of Saint Pancras Cemetery at East Finchley five days later. Many members of the family, friends and representatives from Manchester Corporation convened at the graveside. The Daily Graphic reported the unusual procedure. "As soon as the mourners had gathered round under the shadow of a fine sycamore, of which the leaves have just faded into a beautiful golden brown, the coffin was lowered." Then Moncure Conway, the American freethinker in whose honor Conway Hall in London was later named, delivered a moving and entirely secular address. Many newspapers described Mathilde Blind's beautiful foliage wreath with a "line from Blake woven in gold on a ribbon of black silk: - 'Death is the mercy of eternity'". In fact, Mathilde had deliberately revised Blake's gnomic words from Milton. The original line reads "Time is the mercy of eternity". Mathilde's reworking, while still ambiguous, presumably hints at the agnosticism she shared with the artist. Neither Mathilde nor Madox Brown envisaged an afterlife. In a curious slip, several newspapers reported Mathilde's name incorrectly and called her "Mathilde Brown".

Today Madox Brown's grave is hidden from view in a remote section of the cemetery. A few steps away, in a more accessible position, stands an elegant monument to Mathilde Blind in Carrara marble carved by Edouard Lanteri. It shows Mathilde as a classical goddess, presiding over two graceful female figures, Philosophy and Poetry. Cut beneath her name is the same line she had chosen for Madox Brown's wreath - DEATH IS THE MERCY OF ETERNITY.

Mathilde's own summary of her nomadic life can be found in her unpublished Commonplace Book, in the Bodleian Library. "I have been an exile in this world. Without a God, without a country, without a family." This was the force that impelled the passionate attachments of her life. Her liaison with Madox Brown had been her most meaningful, sustained relationship. "The death of a friend is a grievous affliction but the death of a friendship 'works like madness in the brain'", she thought. "Dear Mathilde", wrote Richard Garnett, "I can very well enter into the sorrow you so touchingly express in your letter, knowing what an incomparable friend you have lost in Madox Brown, and how much you have mutually been to each other." When he published his Memoir of Mathilde, Garnett tactfully categorized Mr. and Mrs. Ford Madox Brown "above all" in a list of her intimate friends. But in careful code he gestured towards the relationship between Mathilde and the painter as "singularly beautiful".

From: Times Literary Supplement (TLS)| Times OnlineI think you should give it some thought and consider how you might feel, if you were Ford Madox Brown on your death-bed, while someone was trimming your beard to look like the 'King of Hearts'. I am not sure I would be pleased, but if I were hooched - I guess it wouldn't make any difference.

Senex Magister

Various Works of Ford Madox Brown

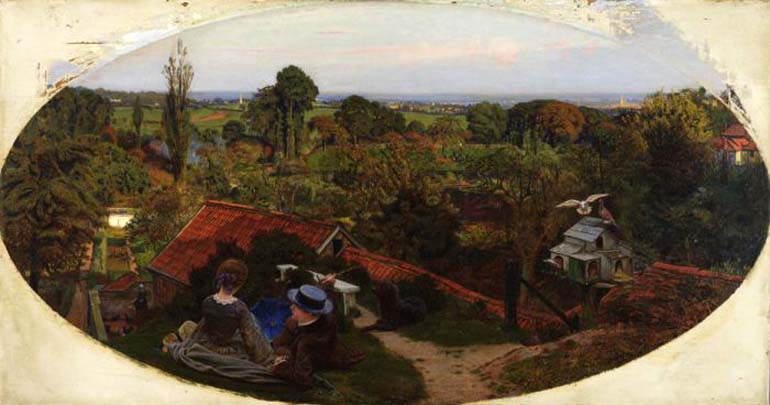

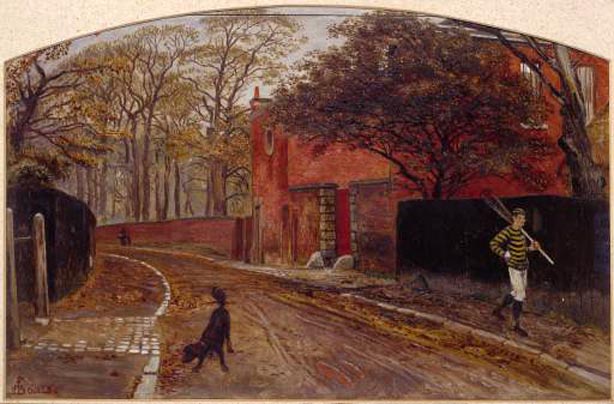

An English Autumn Afternoon: 1852-1853

An English Autumn Afternoon, 1852-1853

After seeing this painting exhibited at the British Institute in 1855 Ruskin commented: 'What made you take such a very ugly subject? It was a pity, for there was some nice painting in it.' Brown replied: 'Because it lay out of a back window.'

Many of the 'modern' subjects Brown chose to paint were inspired by places and events from his own life. This scene is a view of Hampstead from the window of Brown's lodgings and reveals Brown's interest in capturing the light on an autumn afternoon. It was begun in October 1852 but took two years to complete. There are relatively few existing studies for Brown's landscapes and though there are several landscape paintings in Birmingham's collections there is only one drawing relating to landscapes in the collection.

English Autumn

Beata Beatrix: 1877

One of several versions of this subject, this painting was unfinished at the time of Rossetti's death and the background was completed by Ford Madox Brown. The painting is a personal expression of Rossetti's love for his deceased wife, Elizabeth Siddal, seen through the writings of Dante (the subject is taken from 'La Vita Nuova'). In this version, the poppies are red, perhaps an explicit reference to opium-derived laudanum. Another version of the painting is in the Tate collection. There are also numerous related pencil studies in the Birmingham collection, as well as a large ornamental maijolica dish painted with a scene of Rossetti's 'Dante's Dream'.

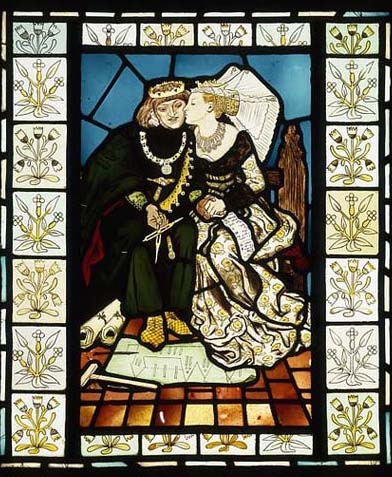

Death of Sir Tristram: 1864

The subject was taken from the story of Sir Tristram and La Belle Iseult as told by Malory in the 'Morte d'Arthur.' The design was originally conceived in September 1862 for a stained glass window produced by Morris, Marshall, Faulkner and Co. The window was one of thirteen illustrating the story for the entrance hall of Harden Grange, near Bingley, the home of Walter Dunlop, a Bradford merchant. In 1863 Brown used the composition for a watercolor and in 1864 he produced this version in oil for George Rae.

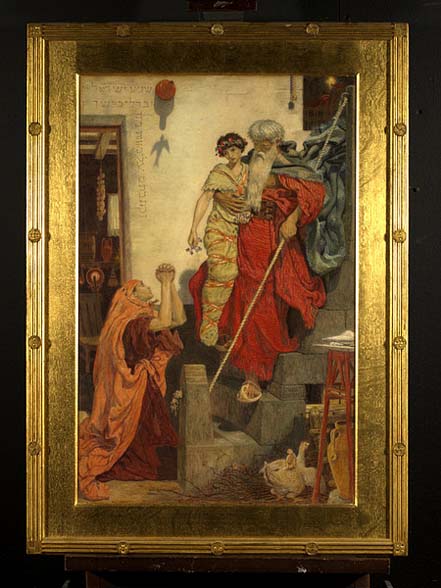

Elijah and the Widow's Son: 1864

In 1863 Brown was commissioned by the Brothers Dalziel to produce three illustrations for a Bible to which many other famous artists of the day were also contributing. This story of a mother whose son is raised from the dead by the prophet Elijah was one of the subjects selected by Brown from a list of possible themes submitted to him by the Brothers.

Having designed the illustration 'Elijah and the Widow's Son' Brown worked up the composition into three paintings. The dealer Gambart bought a small watercolor version, which he later sold to Frederick Leyland (present owner unknown). Frederick Craven of Manchester, a watercolor collector, commissioned a larger version in 1868 (V&A). The painting in the Birmingham collection is the only one in oil and was commissioned in 1864 by a Brighton wine merchant, James Trist, for 100gns. Trist was so pleased with it that he later sent Brown a case of wine.

Finding of Don Juan by Haidee: 1873

This painting developed out of Brown's illustration for 'The Poetical Works of Lord Byron,' published by Moxon in 1870 and edited by William Michael Rossetti. It depicts a scene from the poem 'Don Juan' in which Haidee, the daughter of a Greek pirate, and her nurse Zoe discover the seemingly lifeless body of Don Juan on a beach. There are three other versions of the same composition: an oil at the Musée D'Orsay, Paris, a watercolor at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, and a pastel study at the Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester.

Head of a Page Boy: ca 1837

This is one of Brown's earliest works and is a good example of his youthful style. The palette is somber and dark but the chiaroscuro effect reveals his interest as a student with the old masters, notably Rembrandt and Velasquez. The work is most likely to have been produced between 1835, when Brown began his art training in Belgium and 1845, when he left Paris to move to England. Another picture of the 'Head of a Girl', at Tate, has the same minimal background, dark palette and strong light from the right, and may well have painted at a similar date.

This painting is likely to be the picture listed as 'Head of a Page Boy' and dated 1837 in the list of Brown's major works drawn up by Ford Madox Hueffer, his grandson, in 1896 but from the style and interest in light this date seems a little too early (Ford Madox Brown: A Record of his Life.

Pretty Baa-Lambs: 1851-59

Having successfully experimented with depicting women in eighteenth-century costume in previous compositions such as 'The Infant's Repast,' (1848, Wightwick Manor) Brown chose to continue this theme for his first 'en plein air painting', 'Pretty Baa-lambs' . In earlier paintings he had, like other Pre-Raphaelite artists, painted the landscape outdoors but the figures in the studio. In 'Pretty Baa-lambs' Brown went further and posed his models outdoors, wanting to depict on canvas the effect of bright sunlight exactly as he found it in nature. He described working on the painting in his diary noting that:

"The baa lamb picture was painted almost entirely in sunlight which twice gave me a fever while painting. I used to take the lay figure out every morning and bring it in at night or if it rained. Emma sat for the lady and Kate for the child. The lambs & sheep used to be brought every morning from Clappam common in a truck. One of them eat up all the flowers one morning in the garden where they used to behave very ill. The background was painted on the common."

The landscape was later retouched but a smaller version at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, gives an idea of its original appearance. The meaning of the painting remains ambiguous, Brown insisted that 'this picture was painted out in the sunlight; the only intention being to render the effect as well as my powers in a first attempt of this kind would allow,' however, it also combined the theme of motherhood with an interest in the eighteenth-century, both of which had preoccupied him for the previous two years.

His second wife Emma and their daughter Cathy posed for the mother and child, and Brown hired the sheep from a local farmer.

Walton on the Naze: 1860

The artist and his family stayed in Walton-on-the-Naze, a small town on the Essex coast, in August 1859. The gentleman on the left discussing the beauty of the scene is undoubtedly a self-portrait of Brown. The lady and the little girl, drying their hair after bathing, are his wife Emma and their daughter Catherine. The scene is concerned with the theme of leisure, and the developing mid-nineteenth century interest in tourism. Londoners could reach the resort by steamer - visible on the horizon. The tourists are contrasted against the world of work represented by the stacks of wheat in the foreground, the smoking factory in the background and the ships in the estuary.

Chaucer at the Court of Edward III: 1856-68

Though never officially a member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, this colleague of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Morris was, by inclination and practice, sympathetic to the realist ambitions of the movement. Born in Calais, Madox Brown studied in Belgium and was influenced by the German Nazarene painters in Rome before his first liaison with Pre-Raphaelitism. Working with pure colors and clear contours on a dazzling white ground, and carefully composing his subjects from well-lit life, Brown achieved a sense of pageantry in this tableau. Its lower portions are especially immediate, an extensive cleaning having revealed the glorious condition of the original paintwork. Though Brown began his original composition in Rome, the final canvas was begun in London in 1847, and completed in 1851. Rosetti modeled for Chaucer, while others of the Pre-Raphaelite circle appear as supernumeraries. It was Brown's desire in this, surely one of the greatest modern British paintings in Australia, to encapsulate an historical moment: the birth of the English language in the person of Chaucer. The Tate Gallery in London possesses a study for the work, exact in detail but much reduced in scale

The Seeds and Fruits of English Poetry

Devised to illustrate the ennobling of the English language by Chaucer, this painting was planned in London and composed in Rome in 1845 and completed after Brown's return to England. The central panel shows Geoffrey Chaucer reading at the court of Edward III, with his patron, the Black Prince, on his left. The 'fruits' of English poetry appear in the wings: Milton, Spencer and Shakespeare on the left; Byron, Pope and Burns on the right; Goldsmith and Thomson in the roundels; and, inscribed in the cartouches beneath (held by the children), the names of Campbell, Moore, Shelley, Keats, Chatterton, Kirke White, Coleridge and Wordsworth. Although designed as a sketch for a larger work, Brown omitted the two wings and the Gothic details when he painted his monumental Geoffrey Chaucer reading, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1851.

Mrs. James Madox: 1840

This portrait of the artist's maternal aunt was painted at her home at Foot's Cray, Kent, towards the end of March 1840. It was one of a series of small family portraits made on this visit.

Study for the Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots

The finished painting was begun in Antwerp 1840 and finished in Paris in 1841, where it was exhibited at the Salon (untraced); a smaller version is in the Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester. The sitter for this study of a swooning attendant was the artist's cousin, Elizabeth Bromley, whom he married in 1841.

Lady Rivers and her Children

Elizabeth Woodville, daughter of Earl Rivers and later wife of Edward IV, pleading before the king for the restitution of her dower.

Cromwell Dictating Dispatches to Milton: 1877

In Brown's depiction of Oliver Cromwell he champions the Protestant cause in Catholic Europe. We see him dictating a letter to the Duke of Savoy to protest at his massacre of Swiss Protestants.

The blind man on the left is the poet John Milton, who was then Latin Secretary to Cromwell. The scribe is Andrew Marvell, then Joint Secretary but now better known for his poetry. Brown carefully researched each of these portraits.

Cromwell's role was reassessed by Victorian historians. His legacy of democratic government was appreciated when Victorian England remained politically stable while disruption and revolution rocked much of Europe.

Henry Fawcett and Dame Millicent Garrett Fawcett, nee Garrett

Henry Fawcett, who was blinded in a shooting accident in 1858, had a distinguished career as professor of political economy at Cambridge, (1863-84), and as a Member of Parliament. He was active in the passing of the 1867 Reform Bill and was particularly concerned with the position of women in employment. In this intimate portrait by Ford Madox Brown, Fawcett is seen together with his wife Millicent Garrett Fawcett, and appears to be dictating to her. A leading feminist, she was an active campaigner for women's suffrage and joined the first women's suffrage committee in 1867, the year of her marriage. In 1897 she became president of the influential National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies, which opposed the more militant suffragettes active in the early 1900's. She retired from the presidency after women gained their first, restricted, voting rights in 1918.

Take your Son, Sir: 1851-92

This enigmatic picture shows the artist's second wife, Emma, and their new-born son. The pose is reminiscent of a traditional Madonna and child but the mother's strained expression suggests that this is not a celebration of marriage and motherhood. The domestic details of the room are indicative of a contemporary-life subject in which this could be a kept woman offering her illegitimate child to its father, the figure reflected in the mirror. Ford Madox Brown began this picture in 1851 and although he worked on it over a number of years it remained unfinished at his death.

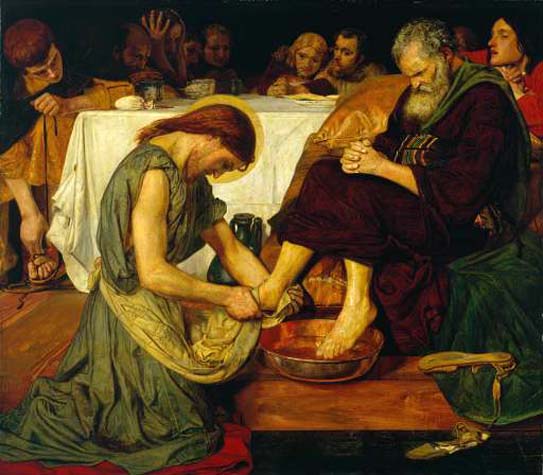

Jesus Washing Peter's Feet: 1852-56

This picture illustrates the biblical story of Christ washing his disciples' feet at the Last Supper. It has an unusually low viewpoint and compressed space. Critics objected to the picture's coarseness - it originally depicted Jesus only semi-clad. This caused an outcry when it was first exhibited and it remained unsold for several years until Ford Madox Brown reworked the figure in robes. Brown was never invited to join the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood but he was a close associate of the group. Several members modeled for the disciples in this picture and the critic F G Stephens sat for Christ.

Portrait of Dykes Barry as a Child: 1853

This portrait was painted in Cheyne Walk in Chelsea, overlooking the River Thames. We know very little more about it. Some under-drawing on the left, of a higher frill and a lower shoulder, suggests that it was painted from life. Ford Madox Brown was a pioneer in seeking objectivity in child portraiture. His pictures emphasized individuality above sentimentality and idealization.

The Brent at Hendon: 1854-55

Brown was born at Calais and studied in Antwerp and Paris before settling in London in 1844. A growing interest in painting subjects in daylight was reinforced by a visit to Italy in 1845-46. Brown was close to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood though never a member of it. Millais' example inspired him to try his hand at painting small landscapes outdoors. This one and 'Carrying Corn' were worked on at the same time, one in the mornings and the other in the afternoons. The Brent picture, the morning work, took Brown most of September 1854 and was then finished in the studio.

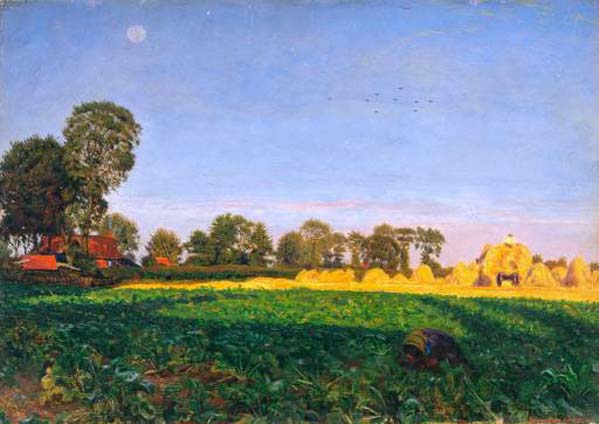

Carrying Corn: 1854-55

This intensely colored painting captures a harvest field just before sunset. Each landscape element is faithfully recorded in jewel-like colors. This is a nostalgic view of rural England, untouched by industrialization and modern city life. Ford Madox Brown's view is typical of idealists of the time who believed that an engagement with nature offered spiritual redemption from urban corruption. Brown and his family were facing financial hardship at the time this picture was painted. It was one of a number of 'potboilers', modest and straightforward landscapes he hoped would sell easily.

The Hayfield: 1855-56

Brown painted this landscape directly from nature. The setting is the Tenterden estate at Hendon, in north London, looking east at twilight. He worked on the picture regularly from July until October 1855, finishing the details of the foreground in his studio, including the self-portrait of an artist relaxing in the lower left corner. The effect he particularly sought to capture was the way in which the brown hay was made to appear almost pink by contrast with the dense green grass. After it was finished his dealer rejected it on the grounds that he had never seen hay of this color. Brown later retouched the painting before selling it to his friend and fellow artist William Morris.

Chaucer at the Court of Edward III: 1856-68

This picture is a replica of Ford Madox Brown's largest and most ambitious painting, exhibited in 1851. It is significant for its portrayal of natural sunlight and reveals his first attempt 'to carry out the notion ...of treating the light and shade absolutely, as it exists at any one moment, instead of approximately or in generalized style'. This pursuit of 'truth to nature' was consistent with Pre-Raphaelite ideals, as was his careful workmanship. The picture's subject, Geoffrey Chaucer, reflects the growing popularity with artists of English literature instead of more conventional classical myths and biblical tales.

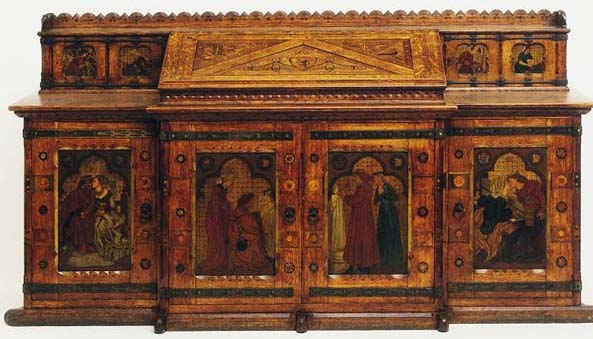

King Rene's Honeymoon: 1864

This watercolor is a replica of the subject Brown painted to decorate a cabinet designed by John Pritchard Seddon, which was made by Morris, Marshall, Faulkner and Company, and is now in the Victoria and Albert Museum. At Brown's suggestion, the painted panels were based on imagined incidents in the honeymoon of King Rene of Anjou, as recounted by Walter Scott in his novel 'Anna von Geierstein'. The four panels on the front of the cabinet illustrate King Rene's renowned interest in the arts. Brown chose to evoke Architecture, showing the King considering the plans for his castle. The other three panels were painted by Rossetti (Music) and Burne-Jones (Painting and Sculpture).

King Rene's Honeymoon: 1864

King Rene's Honeymoon - Architecture

King Rene's Honeymoon Cabinet

J.P. Seddon (1827-1906) designed this architect's desk, including the metalwork and inlay, in 1861 for his own use. Seddon had the desk made at his father's cabinet-making firm. He also commissioned ten painted panels depicting the Fine and Applied Arts from Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co.

Ford Madox Brown (1821-1893), who also designed the panel representing 'Architecture', suggested the overall theme. The 'Painting' and 'Sculpture' panels were by Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898), while Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882) was responsible for 'Music' and 'Gardening'. The other small panels were by Val Prinsep (1838-1904). 'Pottery', 'Weaving', 'Ironwork' (showing William Morris (1834-1896) as a smith) and 'Glass Blowing' are unattributed. Morris designed the decorative background for each panel.

The cabinet depicts scenes from the life of the Medieval King René of Anjou, a notable patron of the arts, as imagined in Sir Walter Scott's novel 'Anne of Geierstein' (Edinburgh, 1829).

Seddon displayed the cabinet in the International Exhibition of 1862, where it received mixed reviews. The South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert) recognized its importance and attempted unsuccessfully to purchase it from the exhibition. The Museum finally acquired it from Seddon's daughter in 1927.

Italian Fisherboy: 1836-1858

This early painting by Madox Brown dates from 1836 and was variously referred to as Fish Boy (account book), Italian Fisher Boy (1858) and The Fisher Boy (1865).

The subject is not listed by Hueffer but is noted in the extant copy of part of the artist's account book (private collection) when the background was finished at Kentish Town in 1858 for exhibition at Liverpool that year.

At the Liverpool Academy, 1858, number 666 was titled Italian Fisher Boy and it was bought by W.D. Holt of the shipping family for 15 guineas (Liverpool Academy Purchase Books). Holt lent it to the artist's own exhibition in Piccadilly in 1865, number 40, where it appeared under the title of The Fisher Boy and the catalogue reads: 'The head and shoulders were painted in 1836 and not retouched. The background added in 1858.'

Other early works dating from 1836 include Head of Flemish Fish Wife, which is untraced, and Blind Beggar and his Child for which a photograph exists.

Portrait of Miss Louie Jones: 1862

Louie Jones, seen in this portrait in evening dress and holding a posy of flowers, was the daughter of Ford Madox Brown's cousin by marriage, William Jones, a solicitor in the City of London, who lived in Greenwich. His wife and the mother of the sitter, Anna, was born a Miss Madox but had died in 1855. According to Ford Madox Brown's Account Book the portrait was begun at Fortess Terrace, Kentish Town, where Brown was living in 1859; he is further recorded as working on it in 1860 and it was finally presented to the sitter in 1862, which is the date given to it in Brown's 1865 Exhibition catalogue.

The portrait reflects Brown's affectionate, almost playful, feelings for his beautiful and elegant cousin. It is quite different in mood to the highly serious, occasionally tragic, themes of the figurative paintings of modern-life subjects by Ford Madox Brown, which were contemporaneous with it.

Cathy Madox Brown: 1853

Cordelia's Portion

The subject is based upon Act 1, Scene 1 of Shakespeare's 'King Lear'. Lear had dispossessed his youngest and favorite daughter Cordelia. Her honesty in answering that she loved her father 'according to her bond' rather than vying with her sisters to suggest that she loved them the most, had led to Lear depriving her of the third of his kingdom that was rightfully hers. Her sisters Goneril and Regan, and their respective husbands, the Dukes of Albany and Cornwall , are shown grasping the crown that Lear has passed to them.

Madox Brown suggests the malevolent intent of these sisters by their mutual gaze. On the right, the King of France looks heavenward and swears love for his future wife, the dowerless Cordelia. The Duke of Burgundy, who will no longer press his suit for Cordelia now that she has been disinherited, stands pensively biting his finger beside Lear's throne. Lear is shown in the grip of vain rage and already appears slightly crazed.

Behind the throne stands the Duke of Gloucester, Lear's fool and three spearmen. To the far left, a small figure gazes back into the room with an arm extended downwards in a distraught gesture. It is likely that he is the Duke of Kent who has suffered banishment for trying to persuade Lear to revoke his foolhardy plans.

Madox Brown's approach to historical probability in this picture is rather fanciful. The King of France wears vaguely fourteenth-century costume, Lear is dressed in a druidical toga, while Cornwall and Albany have some of the stock accompaniments of stage banditti. The mistletoe above Lear's head strikes an authentically ancient British note as do the curiously placed oak leaves in the helmets of Lear's soldiers. Rather less in keeping are the Greek honeysuckle motifs and the imperial griffins on the throne. The tripod table is Roman and the censer, orb and scepter might well have emanated from the workshop of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner and Company. On the foreground map is marked Dover, where the play ends with the death of Lear, Cordelia and her sisters.

La Rose de l'Infante (Effie Stillman): 1876

_1876.jpg)

Mauvais Sujet: 1863

May Memories: 1869-84

Ford Madox Brown began this painting of his second wife, Emma, at his house in Fitzroy Square, London in 1869, retouching and finally working it up for sale in Manchester in May 1884. The year 1870 began as one of some depression does, and held on its course rather languidly. No pictures new in subject were commenced, but designs for pictures, subsequently executed, had their origin in the already referred to illustrations of Moxon's 'Byron'. The early part of the year was occupied by the painting of a fancy portrait' of Mrs. Madox Brown, May Memories, of a lady of sumptuous charms sitting amongst a wealth of may-blossoms, meditating on the glories of her may-days in the 'temps jadis'. This picture was, however, not finished until long subsequently.

During the early part of the year following (1884) the exigencies of his pocket and the prospect of possible sales caused Madox Brown to recur to his old device of retouching and finishing up old pictures, a kind of work that the months of April and May were devoted. The works treated in this way were the pictures of the 'Traveler', an oil replica of that work of sixteen years' standing, and the portrait of Mrs. Madox Brown, called May Memories.

Mercy: ca 1865-70

Our Lady of Good Children: 1847-61

Platt Lane: 1884

A lacrosse player in a shady lane.

Romeo and Juliet: 1870

Saint Elizabeth and Saint John the Baptist

Stages of Cruelty: ca 1856

The composition depicts a young woman spurning her lover, while a little girl in the foreground whips her dog with a bunch of Love-lies-bleeding. Brown used his second daughter Cathy as the model for the young girl, noting in his diary for 1857:

'as Hunt held out some prospect of Fairburn's coming to buy the Lilac leaves, I set at it and painted the convolvulus out in the open air, composed and drew in the child, painted in the Love-lies-Bleeding, worked at the lovers head and at the girls, in all I suppose three weeks.

No commission came and the painting was worked on only intermittently during the 1860's. It was eventually finished in 1890 for Brown's Manchester patron Henry Boddington (and is currently in Manchester Art Gallery). By this time Cathy had children of her own and her daughter Juliet became the model for the girl in the completed canvas.

Study of a Man Painting: 1839

The Coat of Many Colors: 1867

This watercolor illustrates the Old Testament story of Joseph and his coat of many colors. His brothers, jealous of the preference shown towards him by their father, have sold Joseph as a slave. Here we see them duping their father into believing that Joseph has been killed, using the blood-stained coat as evidence.

Unlike other members of the Pre-Raphaelite circle, Brown did not travel to the Near East. However, to give authenticity to the biblical subject matter, he used a watercolor painted by Thomas Seddon in Palestine as inspiration for the background landscape.

The Corsair's Return: ca 1870-81

The Dream of Sardanapalus: 1871

Sardanapalus, a Drama by George Gordon, Lord Byron

The Expulsion from Eden

The Nosegay

Catherine, the artist's daughter, sat for the girl. Unusually for Madox Brown, this picture of a young girl gathering flowers accompanied by her tortoiseshell cat contains no literary or historical meaning and is closer in spirit to the solitary female figure with narrative trappings that Rossetti and Millais worked on.

This is the smaller of two versions (the other is in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) which Madox Brown painted to attract 'Patrons who wanted something pretty'.

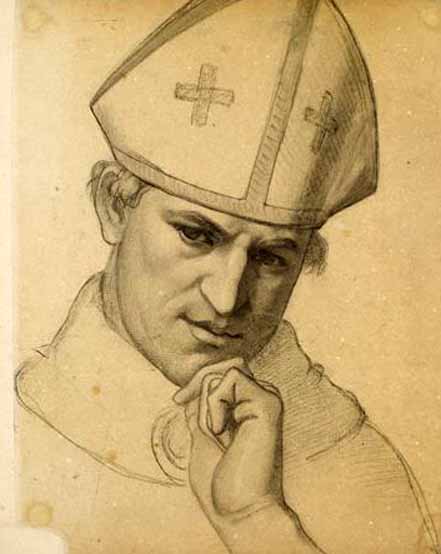

The Spirit of Justice - Study for the Head of a Bishop: 1843-44

This is a study for the Bishop on the right in Ford Madox Brown's cartoon 'The Spirit of Justice.' Brown designed the cartoon in Paris and submitted it to the 1845 Parliament fresco competition. In the allegorical design Justice listens to the case of an impoverished widow wronged by a powerful Baron. She sits on the top tier of the composition with figures symbolizing Mercy, Erudition, Truth and Wisdom. Below her is a row of Kings, noblemen and clergy, the temporal and spiritual advisors. These figures are guarded by a row of knights representing the armed servants of Justice.

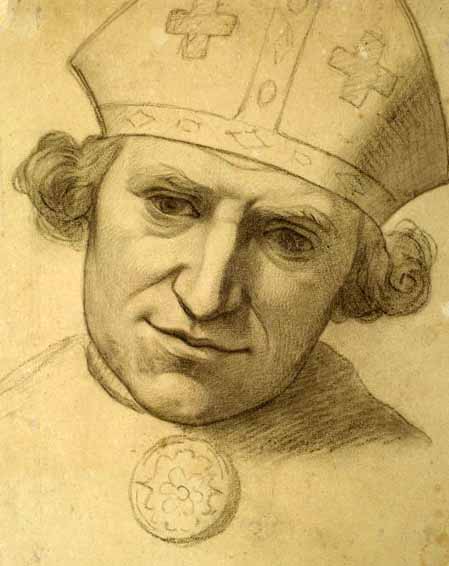

The Spirit of Justice Study for the Head of a Counsellor: ca 1844-45

The Spirit of Justice - Study for Wisdom

The Spirit of Justice Drapery Study for Erudition

The Spirit of Justice - Drapery Study for a Female Figure

The pose of the figure matches that of the central bishop in the finished cartoon but in this drawing it is unclear if the figure is male or female and Brown may have had a slightly different design in mind at the beginning of the project.

The Spirit of Justice - Study for Head of a Bishop: 1843-44

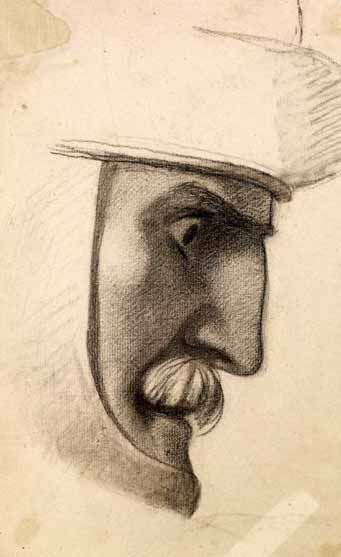

The Spirit of Justice - Study for Head of the Baron

In this allegory Justice is seated in the centre surrounded by counselors who help her preside over the case of a baron accused of murdering a poor widow's husband. This drawing is a study for the face of the baron. The large cartoon now only exists in fragments but a smaller study can be seen in at the Manchester City Art Gallery.

The Spirit of Justice - Study for the Head of a Counsellor

This is a study for the man on the left of Ford Madox Brown's cartoon 'The Spirit of Justice,' wearing a medieval hat.

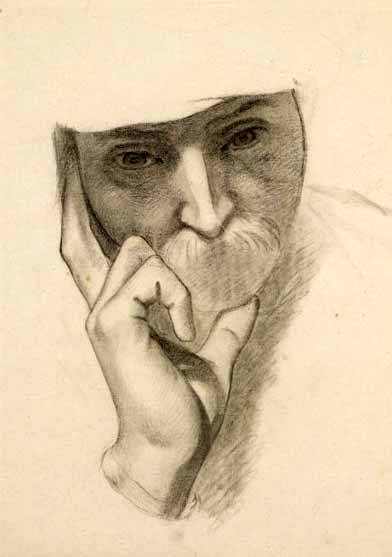

The Spirit of Justice - Study for the Head of the Widow

This is a study for the head of the widow in Brown's cartoon 'The Spirit of Justice'. The allegorical subject depicted a widow, whose husband has been murdered by a baron, appealing to Justice, who is depicted seated on high and surrounded by her counselors. Brown completed most of the cartoon in Paris in 1844 and entered it in the 1845 competition to decorate six arched spaces in the House of Lords. The committee limited the subjects to three allegorical subjects, Religion, Justice and the Spirit of Chivalry, and three histories illustrating these themes: the Baptism of Ethelbert, Prince Henry acknowledging the authority of Chief Justice Gascoigne, and Edward the Black Prince receiving the Order of the Garter from Edward III. These subjects were chosen to reflect the functions of the House of Lords and the relation in which it stands to the Sovereign.

In this drawing Brown has studied the light and shade of each fold of the widow's head scarf and the foreshortening needed to portray her head as she looks up to the assembled figures pleading for justice. On the back of a study for one of the apostles in 'The Ascension' is a sketch of a young child, standing upright and looking up. This appears to be the Widow's child who is depicted clinging to her skirts in the final cartoon.

The Spirit of Justice - Study of the Uplifted Left Arm of the Figure of Justice

This is an anatomical study for the uplifted left arm of the figure of Justice in Ford Madox Brown's cartoon 'The Spirit of Justice.' He designed the cartoon in Paris and submitted it to the 1845 competition to decorate the Houses of Parliament. In the design a widow has brought the baron who murdered her husband before the figure of Justice. Justice is blind and strains to listen cupping her ear to hear the case. Justice's left ear can be seen between the thumb and forefinger in this study.

The Traveller: 1868

View from Shorn Ridgway, Kent

Waiting an English Fireside of 1854-55

This painting started life as an ordinary fireside study and Madox Brown converted it into a topical painting about the Crimean War of 1854 when he took the picture up again in 1855.

This woman is waiting for her soldier husband to return from the Crimea. His miniature portrait can be seen on the table. The woman's shadow, looming behind her also suggests another person missing from this scene.

Ford Madox Brown's wife and daughter posed for the picture. This everyday scene in an ordinary middle-class room lit by lamplight and firelight has been painted with a quiet intensity, suggesting a Madonna and child in contemporary dress.

William Rossetti: 1856

William Michael Rossetti

(1829-1919)

William Michael Rossetti - Wikipedia

Wycliffe Reading his Translation of the Bible

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.