Italian Mannerist Artist

1503 - 1572

"Another cultural rein was taken into the ducal hand in 1563 when Cosimo became president of the newly instituted Accademia del Designo in Florence. With a membership of some seventy painters, sculptors, and architects, with Vasari, Bronzino, and B. Ammanti among the chief organizers, this was the first academy of art to be established in Europe. It had formal rules and was governed by six consuls. It is likely that a majority of the members had already worked for Cosimo.... After the markedly divergent styles that had characterized art in Florence in the first generation of the 16th century, a fairly widely shared style emerged, relying more on gesture than anatomy, on the interrelationships of figures rather than on realization of the space that enclosed them... But once again, Cosimo did not call the academy and his headship of it into being; the initiative came from the artists themselves. When in 1564 the Academy planned an elaborate funeral service for Michelangelo, the most ferociously independent of artists, they petitioned that it should be held in the Medici church of San Lorenzo (although he was to be buried in S. Croce) and they did their utmost to identify the ceremony with the Duke whom Michelangelo had consistantly refused to serve despite repeated invitations. The rein was slipped into Cosimo's hand by painters who wanted the precise opposite of the demeaning guild system to which by law they had to belong. From this law, Cosimo released them in 1571, thus breaking one more link with the republican past from which both prince and painter wanted to escape. (J.R.Hale, "Florence and the Medici", 1977)

Source: Art Renewal Center

Agnolo di Cosimo usually known as Il Bronzino, or Agnolo Bronzino (mistaken attempts also have been made in the past to assert his name was Agnolo Tori and even Angelo (Agnolo) Allori), was an Italian Mannerist painter from Florence. The origin of his nickname, Bronzino is unknown, but could derive from his dark complexion, or from that he gave many of his portrait subjects. It has been claimed by some that he had dark skin as a symptom of Addison's disease, a condition which affects the adrenal glands and often causes excessive pigmentation of the skin.

Bronzino was born in Florence around 1503. According to his contemporary Vasari, Bronzino was a pupil first of Raffaellino del Garbo, and then of Pontormo. The latter was ultimately the primary influence on Bronzino's developing style and the young artist remained devoted to his eccentric teacher. Indeed, Pontormo is thought to have introduced a portrait of Bronzino as a child into one of his series on Joseph in Egypt now in the National Gallery, London. Bronzino's early indebtedness to Pontormo's instruction can be seen in the arresting little Capponi Chapel in Santa Felicita, Florence. During the mid 1520's, the two artists worked together on this commission, though Bronzino is believed to have mostly served as an assistant to his teacher on the masterly Annunciation and The Deposition from the Cross frescoes that adorn the main walls of the chapel. The four tondi that contain images of the evangelists above are more of a mystery: Vasari wrote that Bronzino painted two of them, but his style is so similar to Pontormo's that scholars still debate the specific attributions.

At the end of the third decade of the 16th century Pontormo intensified his formal research. This phase of the painter's artistic career is marked by the decoration of the Cappella Capponi in the church of Santa Felicità in Florence. The chapel, designed by Brunelleschi, and formerly patronized by the Barbadori family, was bought by Ludovico Capponi in 1525, the year in which Pontormo started to work with the assistance of Bronzino. According to Vasari, God the Father and Four Patriarchs, now lost, once decorated the hemispherical cupola, which was apparently replaced by a vault in the 18th century.

Four tondos with the Evangelists still adorn the pendentives that once supported the old cupola. Except for the painting of Saint John, the precise authorship of the other three portraits has posed considerable problems for scholars, who are unable to agree on the extent to which Bronzino contributed in the execution of the paintings. The figures of the Evangelists, with their distinctly Michelangiolesque flavor, have a vigor deriving from the way their heads are twisted and pushed forward. They are wrapped in ample robes, whose bold colors stand out against the dark backgrounds. This play of strong contrasts, which exalts the delicate outlines of the colored surfaces, is in keeping with the refined style of the entire decoration.

The most significant expression of Pontormo's new artistic tendency is undoubtedly the chapel's altarpiece, the painting of the famous Deposition, which can perhaps justly be described as the artist's masterpiece. It was presumably the highly singular artistic innovation of this painting that prompted Pontormo to build a kind of screen which for three years prevented anyone from entering the chapel.

The decoration of the Cappella Capponi is completed by the figure of the Annunciation frescoed on the wall of the window.

The compositional complexity is accompanied by a significant and probably deliberate ambiguity in the representation of the subject, which may be interpreted as halfway between the theme of the Deposition and that of the Pieta or Lamentation over the Dead Christ. The painting appears to represent the moment in which the body of Christ, having been taken down from the cross, has just been removed from the mother's lap. The Virgin, visibly distraught, and perhaps on the point of fainting, still glazes longingly towards her Son, and gestures with her right arm in the same direction. In the centre of the painting, the moment of the separation is underlined by the subtle contact of Mary's legs with those of Christ, now freed from his Mother's last pathetic embrace. The twisted body of Christ is reminiscent of Michelangelo's Vatican Pieta (1498).

An intense spiritual participation in the grief of the event profoundly affects the expressions and attitudes of all the figures present even that of the woman turned away from the onlooker, probably Mary Magdalene, who communicates her anguished psychological condition by reaching out sympathetically towards the swooning body of the Virgin. Some scholars have interpreted the two young figures holding up the deceased's body as angels in the act of drawing Christ away from the main group and leading him finally into the arms of his Father. The general direction of the movement is, in fact, a rising one, and is created by the ethereal quality of the weightless figures, and their slow, almost dance-like rhythm. The two presumed angelic presences, moreover, seem to be unaffected by the weight of the lifeless body, and the figure in the foreground appears to be in the act of raising himself up by lightly pressing down on the front part of his foot.

The intricately connected group of figures, involved in a highly dramatic atmosphere, takes on the appearance of a rich frieze in the harmony of highly refined color tones of pinks, blues and greens. The transparent shadows do not annul the colors, but actually become them, in the flesh tones invested with subtle shades of pink and green.

The cloaked man wearing a strange hat, almost imperceptible against the background of the painting behind the arm of the Virgin may possibly be the artist himself. Staring at something beyond the confines of the painting and looking as though he were about to leave the pictorial space, he presents us with this complex and refined decoration of colors, forms.

_1527_28.jpg)

_Two_1527_28.jpg)

The frescoed figures of the 'Annunciation' belong to the same decorative program as the Deposition. The colors are somewhat deeper than in the 'Deposition', which may be explained, however, by a severe cleaning performed on during eighteenth century. The power of the representation lies more in the form than in any psychological interpretation, which is, in fact, unusual for Pontormo anyway.

The bald Saint John with a long beard seems to share the same uneasy and sorrowful humanity lavished on the body of 'Christ in the Deposition' by Pontormo in the same chapel, this tondo can certainly be attributed to Pontormo. Saint Luke is probably also a contribution by Pontormo.

The figures of the Evangelists, with their distinctly Michelangiolesque flavor, have a vigor deriving from the way their heads are twisted and pushed forward. They are wrapped in ample robes, whose bold colors stand out against the dark backgrounds. This play of strong contrasts, which exalts the delicate outlines of the colored surfaces, is in keeping with the refined style of the entire decoration of the chapel.

Towards the end of his life, Bronzino took a prominent part in the activities of the Florentine Accademia del Disegno, of which he was a founding member in 1563.

The painter Alessandro Allori was his favorite pupil, and Bronzino was living in the Allori family house at the time of his death in Florence in 1572 (Alessandro was also the father of Cristofano Allori). Bronzino spent the majority of his career in Florence.

Bronzino first received Medici patronage in 1539, when he was one of the many artists chosen to execute the elaborate decorations for the wedding of Cosimo I de' Medici to Eleonora di Toledo, daughter of the Viceroy of Naples. It was not long before he became, and remained for most of his career, the official court painter of the Duke and his court. His portrait figures-often read as static, elegant, and stylish exemplars of unemotional haughtiness and assurance-influenced the course of European court portraiture for a century. These well known paintings exist in many workshop versions and copies. In addition to images of the Florentine elite, Bronzino also painted idealized portraits of the poets Dante (ca. 1530, now in Washington, DC) and Petrarch.

ARGUMENT - Saint James questions our Poet concerning Hope. Next Saint John appears; and, on perceiving that Dante looks intently on him, informs him that he, Saint John, had left his body resolved into earth, upon the earth, and that Christ and the Virgin alone had come with their bodies into Heaven.

Bronzino's best known works comprise the above-mentioned series of the Duke and Duchess, Cosimo and Eleonora, and figures of their court such as Bartolomeo Panciatichi and his wife Lucrezia. These paintings, especially those of the Duchess, are known for their minute attention to the detail of her costume, which almost takes on a personality of its own in the image at right. Here the Duchess is pictured with her second son Giovanni, (who died of malaria in 1562, along with his mother); however it is the sumptuous fabric of the dress that takes up more space on the canvas than either of the sitters. Indeed, the dress itself has been the object of some scholarly debate. The elaborate gown has been rumored to be so beloved by the duchess that she was ultimately buried in it; when this myth was debunked, others suggested that perhaps the garment never existed at all and Bronzino invented the entire thing, perhaps working only from a fabric swatch. In any case, this picture was reproduced over and over by Bronzino and his shop, becoming one of the most iconic images of the Duchess.

Bronzino was the best portrayer of the frozen, rigid etiquette of the Grand Duke's court in Florence. His career is interwoven with the history of Mannerism. On which he left his own mark. He happily established himself as the official painter of the Grand Duchy and as the enigmatic stylist of a small circle of cultured aristocrats. Bronzino was first Pontormo's pupil and then for many years his close assistant. With his master he took part in many important jobs in Florence in the 1520's (frescos in the Galluzzo Charter House and decorating the Capponi Chapel in S. Felicita). In 1530 he was summoned to the della Rovere court in the Marches and it was there that he began to paint portraits. It was not long before his outstanding talent in this direction became clear and he started to develop his own style, quite distinct from that of Pontormo. In fact, in addition to his master's almost maniacal insistence on accurate drawing, Bronzino added his own very personal use of color which he applied in a clear and compact fashion that almost gave the effect of varnish.

The firm and glacial way that Bronzino draws outline and detail makes his portraits quite unmistakable. At the same time they possess an almost arrogant grandeur. This leads to a sense of immobile and timeless refinement.

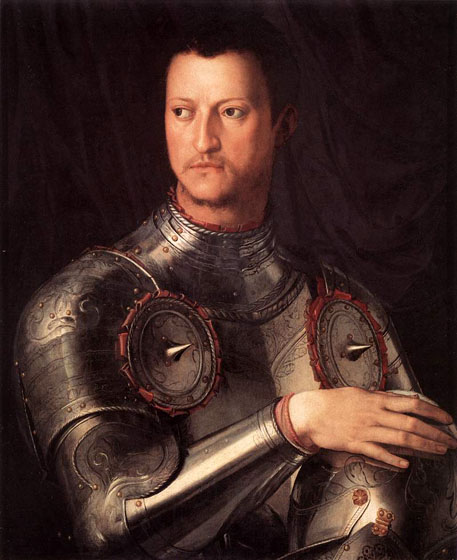

This painting, slightly wooden and less polished than all the other portraits with which Bronzino consigned the members of the Medici family to posterity, must now be regarded as the original of a long series of replicas. (There are less inspired replicas in the Galleria Palatina, the gallery of Kassel and the Metropolitan Museum in New York.) Perhaps the most noteworthy aspect of the painting is the skilful rendering of the armor, the flashing reflections of the metal and the hand resting languidly on the helmet. It is very beautiful in the firm drawing and the hard polish of the planes to an almost metaphysical effect.

It was painted towards 1545, at the happiest moment of Bronzino's activity as a portrait painter. The diligent and frankly enjoyed description of the details of the costume are transfigured, through the geometrical simplification and the calm fixity of the light, into a vision of an almost ecstatic detachment.

Archeological work in the tomb of Eleanora, the wife of Cosimo I de' Medici, has revealed fragments of the dress worn in this portrait.

The boy is dressed in a sumptuous red satin tunic with gold trimmings. His smile reveals two small teeth and in his chubby hands, portrayed with striking naturalism, he holds a colorful little bird. The sphere pendant and the amulet he wears suggested some critics to recognize this child as his younger brother Garzia, born in 1547, to whom could maybe belongs these jewels.

Official portraitist at the Medici court of Cosimo I, Bronzino painted also many portraits of members of Florentine aristocracy or upper middle class.

Colonna, though a Roman, served Duke Cosimo I de' Medici as lieutenant general of the Tuscan army. He was, moreover, a member (as was Bronzino himself) of the Florentine Academy. Colonna died in Pisa in March of 1548, and on the twentieth of that month he received the tribute of an honorary funeral in the Church of San Lorenzo in Florence. The written accounts of this ceremony record that a portrait of the deceased was present: it must have been the one executed by Bronzino. The beautiful frame carries carved symbols that pertain to the art of war and allude to the sitter's qualities as a military commander.

Here the influence of Parmigianino may be obvious, in the elongated figure and the vigorous line which creates broken surfaces on the sleeves of Bartolomeo Panciatichi. The imposing, idealized structure behind the portrait refers to fifteenth-century styles, while the lucid surfaces of color define once again all the ideal and intellectual splendor of this man of the court: a work, therefore, totally in keeping with the taste and mentality of the Florentine painter.

As is typical of Bronzino's art, the lady is dressed sumptuously in warm pink satin and dark velvet. A book is held between her aristocratic hands and her severe, pure face is utterly devoid of any naturalistic beauty. The artist makes this lady of a refined and cultured Florentine society an idealized symbol of chaste beauty (note the delicately, but also chastely gathered hair) and high spirituality.

The portraits of Bartolomeo and Lucrezia Panciatichi mark the transition between the youthful style under the influence of Pontormo and that of the maturity of Bronzino as exemplified in his Medici portraits.

An attribution to Bronzino has not been universally accepted and some scholars have favored an artist from north Italy, specifically from Emilia or Lombardy. The mitigating factor in such an argument lies in the costume which is not Central Italian in style. If the portrait is by Bronzino, then it must be early in date, between the 'Portrait of a Lady with a Lap-dog' (Frankfurt, Stadelsches Kunstinstitut) or the 'Portrait of a Boy with a Book', dating from the early 1530's (Milan, Castello Sforzesca, Trivulzio collection), and the 'Portrait of a Young Man with a Lute' (Florence, Uffizi) or the 'Portrait of Ugolino Martelli', dating from the mid-1530's (Berlin, Staatliche Museen). It was at the beginning of this decade that Bronzino worked in Pesaro for the court of Urbino (1530-2) and it is possible that he took the opportunity to travel in Emilia, to places like Bologna, Ferrara or Modena. Alternatively, north Italian fashions could have been seen in the Marches, either at Urbino itself or in Pesaro, owing to the strong dynastic connections between Italian courts.

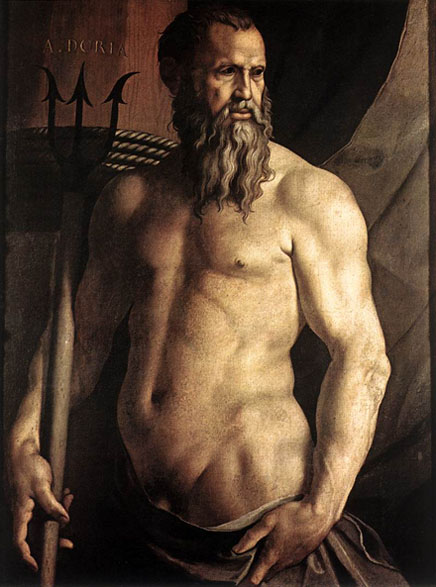

Bronzino's so-called 'allegorical portraits,' such as that of a Genoese admiral, Andrea Doria as Neptune, is less typical but possibly even more fascinating due to the peculiarity of placing a publicly recognized personality in the nude as a mythical figure. Finally, in addition to being a painter, Bronzino was also a poet, and his most personal portraits are perhaps those of other literary figures such as that of his friend Laura Battiferri, wife of sculptor/architect Bartolommeo Ammanati.

This complex allegory represents Happiness (in the centre) with Cupid, flanked by Justice and Prudence. At her feet are Time and Fortune, with the wheel of destiny and the enemies of peace lying humiliated on the ground. Above the head of Happiness is Fame sounding a trumpet, and Glory holding a laurel garland. This Happiness, with the cornucopia, is a triumph of pink and blue; the naked bodies of the figures are smooth, almost stroked by the color as if they were precious stones - round and well-defined those of the young women, haggard and leaden that of the old man.

_1540_45.jpg)

The goddess of love and beauty identified by the golden apple given to her by Paris and by her doves, has drawn Cupid's arrow. At her feet, masks, perhaps the symbols of sensual nymph and satyr seem to gaze up at the lovers. Foolish Pleasure, the laughing child, throws rose petals at them, heedless of the thorn piercing his right foot. Behind him Deceit, fair of face, but foul of body, proffers a sweet honeycomb in one hand, concealing the sting in her tail with the other. On the other side of the lovers is a dark figure, formerly called Jealousy but recently plausibly identified as the personification of Syphilis, a disease probably introduced to Europe from the New World and reaching epidemic proportions by 1500.

The symbolic meaning of the central scene is thus revealed to be unchaste love, presided over by Pleasure and abetted by Deceit, and its painful consequences. Oblivion, the figure on the upper left who is shown without physical capacity for remembering, attempts to draw a veil over all, but is prevented by Father Time - possibly alluding to the delayed effects of syphilis. Cold as marble or enamel, the nudes are deployed against the costliest ultramarine blue, and the whole composition, flattened against the picture plane, recalls Bronzino's contemporaneous designs for the duke's new tapestry factories.

In 1540/41, Bronzino began work on the fresco decoration of the Chapel of Eleanora di Toledo in the Palazzo Vecchio. Elegant and classicizing, these religious works are excellent illustrations of the mid-16th-century aesthetics of the Florentine court, traditionally interpreted as highly-stylized and non-personal or emotive. The Crossing the Red Sea is typical of Bronzino's approach at this time, though it should not be claimed that Bronzino or the court was lacking in religious fervor on the basis of the preferred court fashion. Indeed, the Duchess Eleanora was a generous patron to the recently founded Jesuit order.

The bald Saint John with a long beard seems to share the same uneasy and sorrowful humanity lavished on the body of 'Christ in the Deposition' by Pontormo in the same chapel, this tondo can certainly be attributed to Pontormo. Saint Luke is probably also a contribution by Pontormo.

The figures of the Evangelists, with their distinctly Michelangiolesque flavor, have a vigor deriving from the way their heads are twisted and pushed forward. They are wrapped in ample robes, whose bold colors stand out against the dark backgrounds. This play of strong contrasts, which exalts the delicate outlines of the colored surfaces, is in keeping with the refined style of the entire decoration of the chapel.

This altarpiece was executed for the Chapel of Eleanora in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. The chapel is located on the second floor of the palace and it served as the private chapel of the Duchess, Eleanora of Toledo, daughter of the Viceroy of Naples, and wife of Cosimo I de' Medici. The painting occupied the end wall of the small chapel flanked by Saint John the Baptist and Saint Cosmas.

The painting was finished in 1545 and was sent in the same year to Besancon to the private secretary of Emperor Charles V with whom Cosimo had important negotiations. Since 1553 a replica by Bronzino replaces the altarpiece. Later the two side panels were also replaced by the figures of an Annunciation.

The state of preservation of the painting is very poor. The decline of the aging artist, who relied increasingly on assistants, can be seen in the complex composition.

The painting has a structure which is dynamic, abstract, yet at the same time frozen by sharp outlines, typical of Bronzino. Everything is harmoniously arranged in a great compositional balance, albeit of considerable complexity. In the foreground the group of the Virgin and Saint Joseph is built up with revolving movements, which are restrained below by the extremely smooth bodies of the two children. The delicate face of the Madonna, her almost chiseled hair, and the pose and form of her hands, closely resemble elements in Bronzino's famous portrait of Lucrezia Panciatichi.

The grandiose and tormented plasticity of Michelangelo is here interpreted, by means of the smooth polish of the planes under a motionless, marble light, in pseudo-classic taste.

The painting is named the 'Stroganoff Holy Family' after its former owner.

For the decoration of the chapel Bronzino applied an unusual technique: the under painting was true fresco and the finished layer in tempera. The combination of complex figural compositions, rich colors, and elaborate decorative motifs within the chapel's small space create a bejeweled effect typical of Mannerism as practiced at the court of Cosimo and Eleanora.

The altarpiece currently in the chapel, depicting the Lamentation, is a replica Bronzino made in 1553 of his 1545 original (which was sent to France as a diplomatic gift). Bronzino also removed the original flanking panels of Saint John the Baptist and Saint Cosmas and replaced them with side panels depicting the Annunciation.

Bronzino's work tends to include sophisticated references to earlier painters, as in The Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence (1569), in which almost every one of the extraordinarily contorted poses can be traced back to Raphael or to Michelangelo, who Bronzino idolized. Bronzino's skill with the nude was even more enigmatically deployed in the celebrated Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time, which conveys strong feelings of eroticism under the pretext of a moralizing allegory. His other major works include the design of a series of tapestries on The Story of Joseph, for the Palazzo Vecchio.

Many of Bronzino's works are still in Florence but other examples can be found in the National Gallery, London, and elsewhere.

_1560.jpg)

Source: Wikipedia

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.