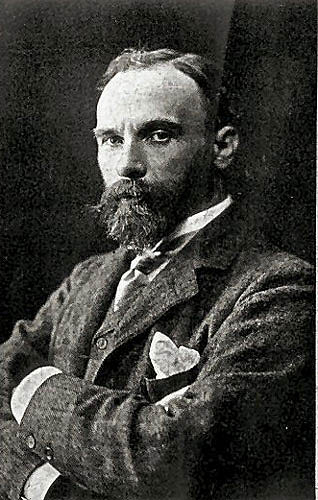

English Pre-Raphaelite Painter and Draftsman

1849 - 1917

He was born in Rome to the painters William and Isabela Waterhouse, but when he was five the family moved to South Kensington, near the newly founded Victoria and Albert Museum. He studied painting under his father before entering the Royal Academy schools in 1870. His early works were of classical themes in the spirit of Alma-Tadema and Frederic Leighton, and were exhibited at the Royal Academy, the Society of British Artists and the Dudley Gallery.

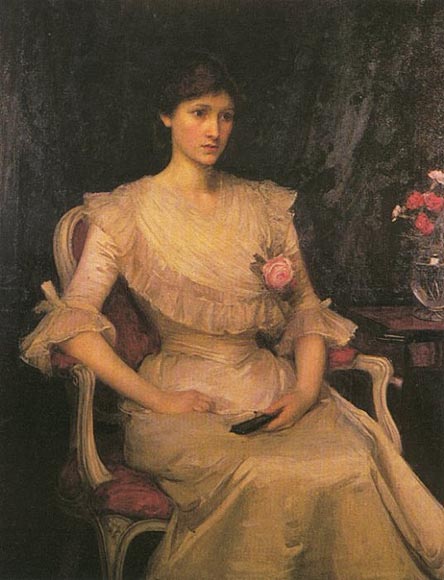

In 1874, at the age of twenty-five, Waterhouse submitted the classical allegory Sleep and His Half-Brother Death to the Royal Academy's Summer Exhibition. The painting was very well received and he exhibited at the RA almost every year afterwards until his death in 1917. In 1883 he married Esther Kenworthy, the daughter of an art schoolmaster from Ealing who had exhibited her own flower-paintings at the Royal Academy and elsewhere. They had two children, but both died in childhood.

In 1895 Waterhouse was elected to the status of full Academician. He taught at the St. John's Wood Art School, joined the St John's Wood Arts Club, and served on the Royal Academy Council.

One of Waterhouse's most famous paintings is The Lady of Shalott, a study of Elaine of Astolat, who dies of grief when Lancelot will not love her. He actually painted three different versions of this character, in 1888, 1896, and 1916.

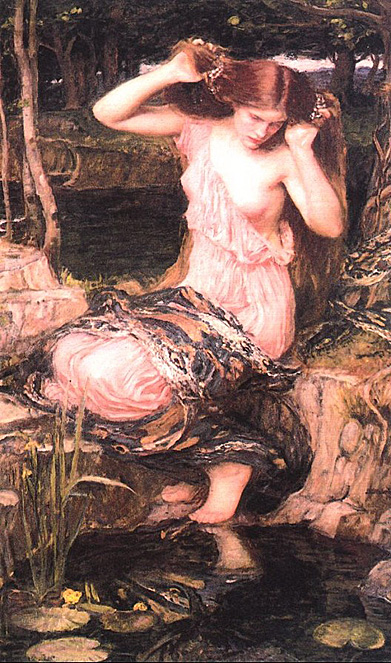

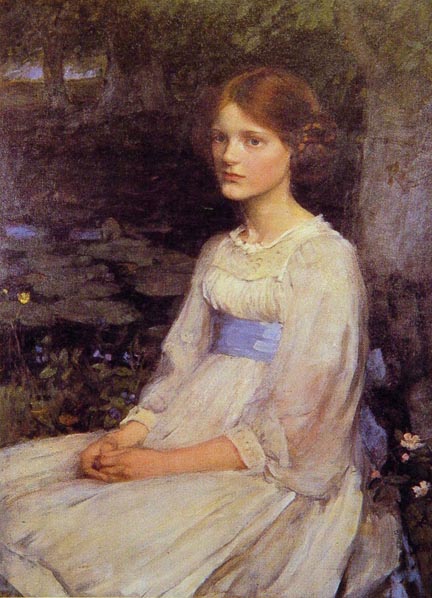

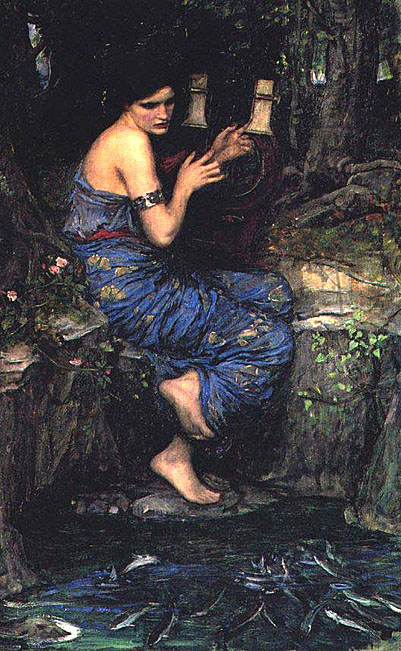

Another of Waterhouse's favorite subjects was Ophelia; the most famous of his paintings of Ophelia depicts her just before her death, putting flowers in her hair as she sits on a tree branch leaning over a lake. Like The Lady of Shallot and other Waterhouse paintings, it deals with a woman dying in or near water. He also may have been inspired by paintings of Ophelia by Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Millais. He submitted his Ophelia painting of 1888 in order to receive his diploma from the Royal Academy. (He had originally wanted to submit a painting titled "A Mermaid", but it was not completed in time.) After this, the painting was lost until the 20th century, and is now displayed in the collection of Lord Andrew Lloyd-Webber. Waterhouse would paint Ophelia again in 1894 and 1909 or 1910, and planned another painting in the series, called "Ophelia in the Churchyard."

Waterhouse could not finish the series of Ophelia paintings because he was gravely ill with cancer by 1915. He died two years later, and his grave can be found at Kensal Green Cemetery in London.

. Waterhouse fully captured the Lady in her crazed, frantic state, desperately trying to reach Camelot, dying as she goes. On the front of the boat surrounded by candles lies a cross, with the image of Jesus nailed to it, symbolizing her willingness to sacrifice her life for love. The tapestry she is sitting on is one she wove on her loom, depicting scenes of Camelot. The two images on the tapestry that can be seen are the Lady of Shalott herself riding toward Camelot in the boat, and sir Lancelot on a horse surrounded by other knights.

Part I.

On either side the river lie

Long fields of barley and of rye,

That clothe the wold and meet the sky;

And thro' the field the road runs by

To many-tower'd Camelot;

And up and down the people go,

Gazing where the lilies blow

Round an island there below,

The island of Shalott.

Willows whiten, aspens quiver,

Little breezes dusk and shiver

Thro' the wave that runs for ever

By the island in the river

Flowing down to Camelot.

Four gray walls, and four gray towers,

Overlook a space of flowers,

And the silent isle imbowers

The Lady of Shalott.

By the margin, willow-veil'd

Slide the heavy barges trail'd

By slow horses; and unhail'd

The shallop flitteth silken-sail'd

Skimming down to Camelot:

But who hath seen her wave her hand?

Or at the casement seen her stand?

Or is she known in all the land,

The Lady of Shalott?

Only reapers, reaping early

In among the bearded barley,

Hear a song that echoes cheerly

From the river winding clearly,

Down to tower'd Camelot:

And by the moon the reaper weary,

Piling sheaves in uplands airy,

Listening, whispers "'Tis the fairy

Lady of Shalott."

Part II.

There she weaves by night and day

A magic web with colours gay.

She has heard a whisper say,

A curse is on her if she stay

To look down to Camelot.

She knows not what the curse may be,

And so she weaveth steadily,

And little other care hath she,

The Lady of Shalott.

And moving thro' a mirror clear

That hangs before her all the year,

Shadows of the world appear.

There she sees the highway near

Winding down to Camelot:

There the river eddy whirls,

And there the surly village-churls,

And the red cloaks of market girls,

Pass onward from Shalott.

Sometimes a troop of damsels glad,

An abbot on an ambling pad,

Sometimes a curly shepherd-lad,

Or long-hair'd page in crimson clad,

Goes by to tower'd Camelot;

And sometimes thro' the mirror blue

The knights come riding two and two:

She hath no loyal knight and true,

The Lady of Shalott.

But in her web she still delights

To weave the mirror's magic sights,

For often thro' the silent nights

A funeral, with plumes and lights

And music, went to Camelot:

Or when the moon was overhead,

Came two young lovers lately wed;

"I am half-sick of shadows," said

The Lady of Shalott.

Part III.

A bow-shot from her bower-eaves,

He rode between the barley-sheaves,

The sun came dazzling thro' the leaves,

And flamed upon the brazen greaves

Of bold Sir Lancelot.

A redcross knight for ever kneel'd

To a lady in his shield,

That sparkled on the yellow field,

Beside remote Shalott.

The gemmy bridle glitter'd free,

Like to some branch of stars we see

Hung in the golden Galaxy.

The bridle-bells rang merrily

As he rode down to Camelot:

And from his blazon'd baldric slung

A mighty silver bugle hung,

And as he rode his armour rung,

Beside remote Shalott.

All in the blue unclouded weather

Thick-jewell'd shone the saddle-leather,

The helmet and the helmet-feather

Burn'd like one burning flame together,

As he rode down to Camelot.

As often thro' the purple night,

Below the starry clusters bright,

Some bearded meteor, trailing light,

Moves over still Shalott.

His broad clear brow in sunlight glow'd;

On burnish'd hooves his war-horse trode;

From underneath his helmet flow'd

His coal-black curls as on he rode,

As he rode down to Camelot.

From the bank and from the river

He flash'd into the crystal mirror,

"Tirra lirra," by the river

Sang Sir Lancelot.

She left the web, she left the loom,

She made three paces thro' the room,

She saw the water-lily bloom,

She saw the helmet and the plume,

She look'd down to Camelot.

Out flew the web and floated wide;

The mirror crack'd from side to side;

"The curse is come upon me," cried

The Lady of Shalott.

Part IV.

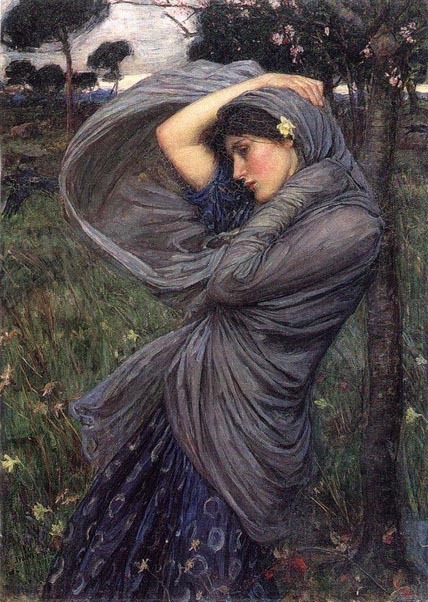

In the stormy east-wind straining,

The pale-yellow woods were waning,

The broad stream in his banks complaining,

Heavily the low sky raining

Over tower'd Camelot;

Down she came and found a boat

Beneath a willow left afloat,

And round about the prow she wrote

The Lady of Shalott.

And down the river's dim expanse--

Like some bold seër in a trance,

Seeing all his own mischance--

With a glassy countenance

Did she look to Camelot

.

And at the closing of the day

She loosed the chain, and down she lay;

The broad stream bore her far away,

The Lady of Shalott.

Lying, robed in snowy white

That loosely flew to left and right--

The leaves upon her falling light--

Thro' the noises of the night

She floated down to Camelot:

And as the boat-head wound along

The willowy hills and fields among,

They heard her singing her last song,

The Lady of Shalott.

Heard a carol, mournful, holy,

Chanted loudly, chanted lowly,

Till her blood was frozen slowly,

And her eyes were darken'd wholly,

Turn'd to tower'd Camelot;

For ere she reach'd upon the tide

The first house by the water-side,

Singing in her song she died,

The Lady of Shalott.

Under tower and balcony,

By garden-wall and gallery,

A gleaming shape she floated by,

A corse between the houses high,

Silent into Camelot.

Out upon the wharfs they came,

Knight and burgher, lord and dame,

And round the prow they read her name,

The Lady of Shalott.

Who is this? and what is here?

And in the lighted palace near

Died the sound of royal cheer;

And they cross'd themselves for fear,

All the knights at Camelot:

But Lancelot mused a little space;

He said, "She has a lovely face;

God in his mercy lend her grace,

The Lady of Shalott."

Karya (Nut tree)

Balanos (Acorn tree)

Kraneia (Cornel tree)

Morea (Mulberry tree)

Aigeiros (Black Poplar tree)

Ptelea (Elm tree)

Ampelos (Vines)

Syke (Fig tree)

Much like sirens, mermaids in stories would sometimes sing to sailors and enchant them, distracting them from their work and causing them to walk off the deck or cause shipwrecks. Other stories would have them squeeze the life out of drowning men while trying to rescue them. They are also said to take them down to their underwater kingdoms. In Hans Christian Andersen's The Little Mermaid it is said that they forget that humans cannot breathe underwater, while others say they drown men out of spite.

The Sirens of Greek mythology are sometimes portrayed in later folklore as mermaid-like; in fact, some languages use the same word for both creatures. Other related types of mythical or legendary creature are water fairies and selkies, animals that can transform themselves from seals to humans.

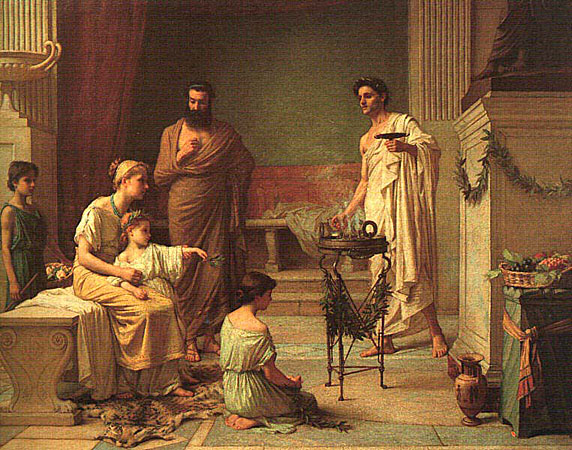

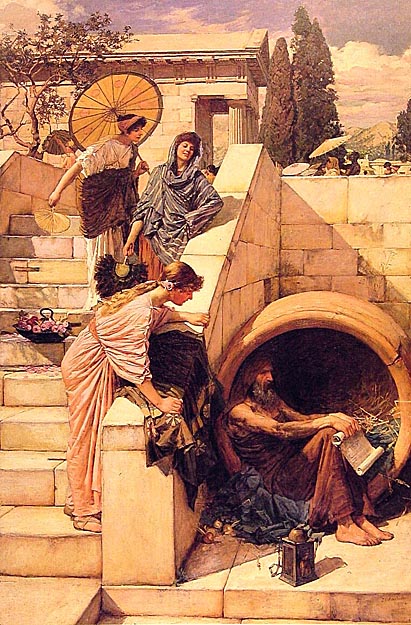

Coronis (or Arsinoe) became pregnant with Asclepius by Apollo but fell in love with Ischys, son of Elatus. A crow informed Apollo of the affair and he sent his sister, Artemis, to kill Coronis. Her body was burned on a funeral pyre, staining the white feathers of the crows permanently black. Apollo rescued the baby by performing the first caesarean section and gave it to the centaur Chiron to raise. Enraged by his grief, Coronis' father Phlegyas torched the Apollonian temple at Delphi, for which Apollo promptly killed him.

Chiron taught Asclepius the art of surgery, teaching him to be the most well-respected doctor of his day. According to the Pythian Odes of Pindar, Chiron also taught him the use of drugs, incantations and love potions. In The Library, Apollodorus claimed that Athena gave him a vial of blood from the Gorgons. Gorgon blood had magical properties: if taken from the left side of the Gorgon, it was a fatal poison; from the right side, the blood was capable of bringing the dead back to life. According to some, Asclepius fought alongside the Achaeans in the Trojan War, and cured Philoctetes of his famous snake bite. However, others have attributed this to either Machaon or Podalirius, Asclepius' sons, who Homer mentions repeatedly in his Iliad as talented healers. Asclepius, on the other hand, is only referred to by Homer in relation to Machaon and Podalirius.

Asclepius' powers were not appreciated by all, and his ability to revive the dead soon drew the ire of Zeus, who struck him down with a thunderbolt. According to some, Zeus was angered, specifically, by Asclepius' acceptance of money in exchange for resurrection. Another story says Asclepius healed people and may have even made them immortal. This was unacceptable to the god of the Underworld, Hades, who considered these souls his rightful property. Hades prevailed upon Zeus, his brother and king of the gods, to hurl a lightning bolt through Asclepius's head. Zeus proclaimed that all of medicine thereafter could only be palliative -- make the person more comfortable while they either die or get well on their own -- but cures were not allowed. Others say that Zeus killed Asclepius after he agreed to resurrect Hippolytus at the behest of Artemis. Zeus may or may not have smitten Hippolytus with the same bolt. Either way, Asclepius' death at the hands of Zeus may symbolize man's inability to challenge the natural order that separates mortal men from the gods.

Zeus, saddened at the loss of the original three Cyclops, decided to return them from Hades. Apollo also persuaded him to bring Asclepius back. Zeus consented after much begging and made Asclepius and his daughters, deities of medicine, after bringing them to Olympus, much to Apollo's joy.

After he realized Asclepius' importance to the world of men, Zeus placed him in the sky as the constellation Ophiuchus. The name, "serpent-bearer," refers to the Rod of Asclepius, which was entwined with a single serpent. This symbol has now become a symbol for physicians across the globe. However, one should be careful not to confuse the Staff of Asclepius, which features a single serpent wrapped around a roughhewn branch, with the Caduceus of Mercury (Roman), or Karykeion of Hermes (Greek). The Caduceus which features two intertwined serpents (rather than the single serpent in Asclepius' wand as well as a pair of wings has long been a symbol of commerce. It is thought that the two were first confused in the seventh century A.D., when alchemists often used the caduceus to symbolize their association with magical or "hermetic" arts.

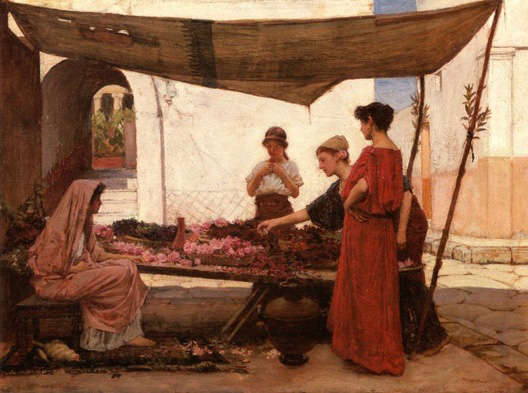

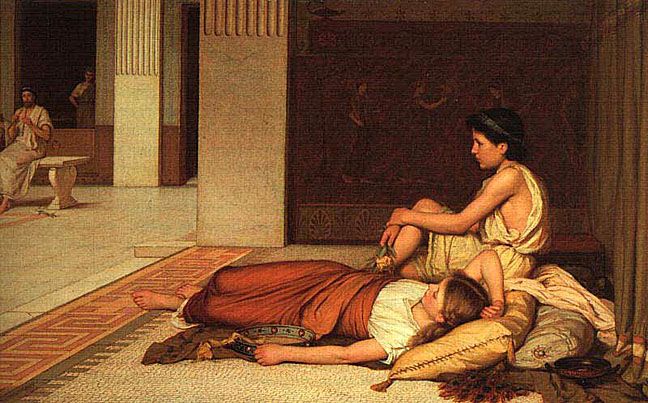

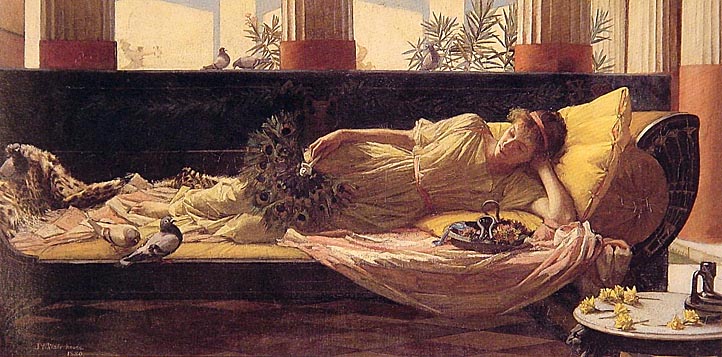

'...two Greek girls, gracefully draped, resting themselves in the atrium of the house wherein they have been dancing. The coloring is quiet, and yet not without a certain richness, the prevailing tints being yellow, green, brown and grey. One girl lies on her back, the other sits at her side...'

Geoffrey Chaucer (c.1343-1400), 'The Legend of Good Women'

Each year, as payment for the slaughter of Minos' son, the Athenians offered a tribute of youths and maidens to the monstrous Minotaur that dwelt in the Cretan labyrinth. Designed by Dedalus, the labyrinth was built of such complexity that nobody had ever escaped from its confines. Ariadne's father, Minos, the King of Crete, selected Theseus as part of the offering, but on his arrival at the island Ariadne fell in love with him and, loath to see him die, secretly gave him a spool of thread by which he could trace his way from the maze. Theseus slew the Minotaur and fled from Crete, carrying Ariadne away as his wife, but when they arrived at the island of Naxos the Olympic gods shrouded his mind with forgetfulness and he deserted her while she lay asleep.

The painting was sold for £848,500 ($1,293,962) - the record price for a Waterhouse at the time.

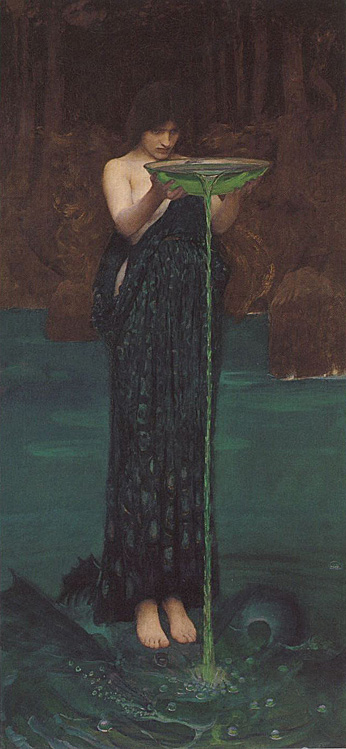

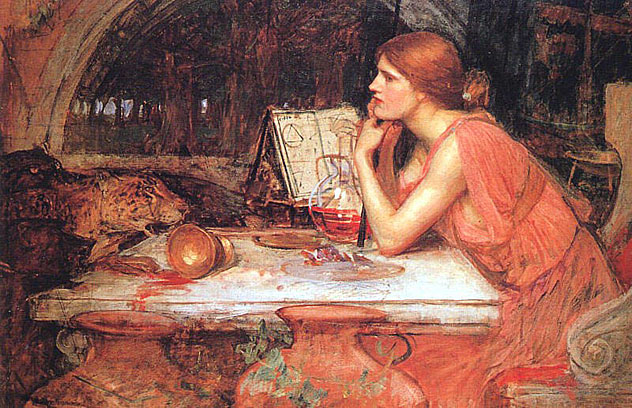

Waterhouse portrays Circë, cup in one hand, wand in the other, surrounded by purple flowers, the color of royalty, offering the potion to Ulysses. She thinks herself a queen. She sits on a golden throne, roaring lions depicted on each arm. By her side lies a pig, perhaps one of Ulysses' men. There are other animals portrayed in the painting depicting other mortals who fell into Circë's grasp, including a toad in the foreground and a duck which can be seen reflected in the left side of the mirror behind her. Also in the mirror, Ulysses himself can be seen fists clenched, ready to attack.

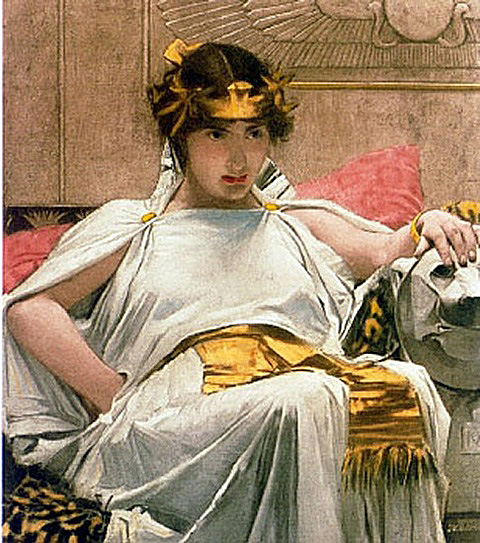

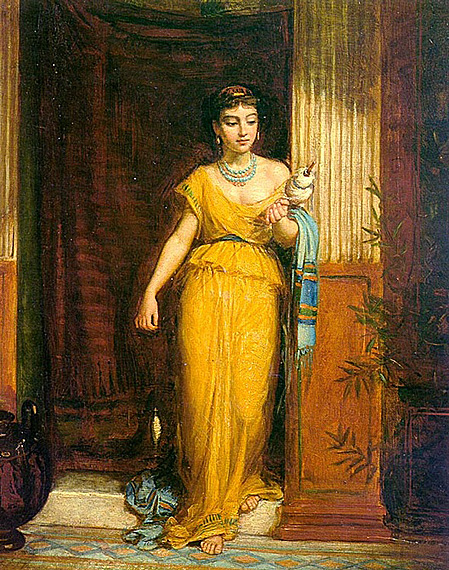

She is the Egyptian queen famous in history and drama who was the lover of Julius Caesar and later the wife of Mark Antony. She became queen on the death of her father, Ptolemy XII, in 51 BC, ruling successively with her two brothers Ptolemy XIII (51-47) and Ptolemy XIV (47-44) and her son Ptolemy XV Caesar (44-30). After the Roman armies of Octavian (the future Emperor Augustus) defeated their combined forces, Antony and Cleopatra committed suicide, and Egypt fell under Roman domination. Her ambition no less than her charm actively influenced Roman politics at a crucial period, and she came to represent, as did no other woman of antiquity, the prototype of the romantic femme fatale

.

Durante degli Alighieri better known as Dante was an Italian Florentine poet. His greatest work, La Divina Commedia (The Divine Comedy), is considered the greatest literary statement produced in Europe in the medieval period, and the basis of the modern Italian language.

Dante was nearly nine years old when he first set eyes on Beatrice Portinari, in a gathering at her father's palazzo in Florence. She was a few months younger than Dante and dressed in a crimson dress. She captivated him completely. As he later wrote, "From that time forward love fully ruled my soul." For the next nine years he remained absolutely besotted with her but only from a distance and it was only in 1283, when he was 18, that she spoke to him as they passed each other in the street.

In 13th century Florence arranged marriages were the norm, especially amongst the uppers classes, to which both Dante and Beatrice belonged. So, at the age of 21 Dante was married off to Gemma Donati, to whom he had been betrothed since the age of 12 and Beatrice married a year later too, only to die three years after that, at the tender age of 24. Dante was devastated. He remained devoted to Beatrice for the rest of his life and she was his principal inspiration for much of his well known work, such as La Vita Nuova (The New Life) and La Divina Commedia (The Divine Comedy).

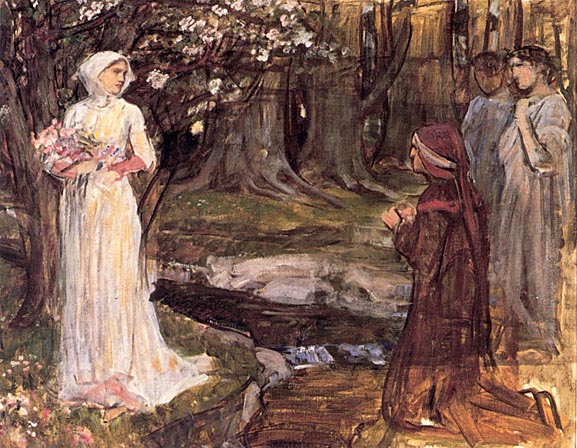

When Dante first saw Beatrice, he tells us she was dressed in soft crimson and wore a girdle about her waist. He fell in love with her at first sight and thought of her as angelic with divine and noble qualities. He frequented places where he could catch a glimpse of her, but she never spoke to him until nine years later. Then one afternoon he saw her dressed in white, walking down a street in Florence. Accompanied by two older women, Beatrice turned and greeted him. Her greeting filled him with such joy that he retreated to his room to think about her. Falling asleep, he had a dream that became the subject of the first sonnet in his La Vita Nuova, one of the world's greatest romantic poems. Two chapters from La Vita Nuova are quoted below:

When exactly nine years had passed since this gracious being appeared to me, as I have described, it happened that on the last day of this intervening period this marvel appeared before me again, dressed in purest white, walking between two other women of distinguished bearing, both older than herself. As they walked down the street she turned her eyes toward me where I stood in fear and trembling, and with her ineffable courtesy, which is now rewarded in eternal life, she greeted me; and such was the virtue of her greeting that I seemed to experience the height of bliss. It was exactly the ninth hour of day when she gave me her sweet greeting. As this was the first time she had ever spoken to me, I was filled with such joy that, my senses reeling, I had to withdraw from the sight of others. So I returned to the loneliness of my room and began to think about this gracious person. (La Vita Nuova III)

Whenever and wherever she appeared, in the hope of receiving her miraculous salutation I felt I had not an enemy in the world. Indeed, I glowed with a flame of charity which moved me to forgive all who had ever injured me; and if at that moment someone had asked me a question, about anything, my only reply would have been: 'Love', with a countenance clothed with humility. When she was on the point of bestowing her greeting, a spirit of love, destroying all the other spirits of the senses, drove away the frail spirits of vision and said: 'Go and pay homage to your lady'; and Love himself remained in their place. Anyone wanting to behold Love could have done so then by watching the quivering of my eyes. And when this most gracious being actually bestowed the saving power of her salutation, I do not say that Love as an intermediary could dim for me such unendurable bliss but, almost by excess of sweetness, his influence was such that my body, which was then utterly given over to his governance, often moved like a heavy, inanimate object. So it is plain that in her greeting resided all my joy, which often exceeded and overflowed my capacity. (La Vita Nuova XI)

John Milton (1608-1674), 'Comus'

Punished by a goddess for her constant chatter, Echo was confined to repeating the words of others. Enamoured of Narcissus, the son of the river god Cephisus and the nymph Liriope, she tried to win his love using fragments of his own speech but he spurned her attentions. Passing by a stream, the beautiful youth caught a glimpse of his reflection is a stream and became transfixed by the lovely image. Believing it to be the form of a nymph, he vainly courted the watery mirage and wasted away through unrequited love. He was transformed into the flower that bears his name and Echo pined away until nothing but her voice remained.

Rosamond was a mistress of Henry II of England. She was the subject of many legends and stories.

Rosamond is believed to have been the daughter of Walter de Clifford of the family of Fitz-Ponce (the ruins of the castle where she was born are located just outside the book town of Hay-on-Wye, Wales). She is said to have been Henry's mistress secretly for several years but was openly acknowledged by him only when he imprisoned his wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine, as a punishment for encouraging her sons in the rebellion of 1173-74. Rosamond died in or about 1176 and was buried in the nunnery church of Godstow before the high altar. The body was removed by order of St. Hugh, bishop of Lincoln, in 1191 and was, seemingly, reinterred in the chapter house.

The story that she was poisoned by Queen Eleanor first appears in the French Chronicle of London in the 14th century. The romantic details of the labyrinth at Woodstock, including the clue that guided King Henry II to her bower, were the inventions of storywriters of later times. There is no evidence to support the popular belief that she was the mother of Henry's natural son William Longsword, Earl of Salisbury.

Robert Herrick

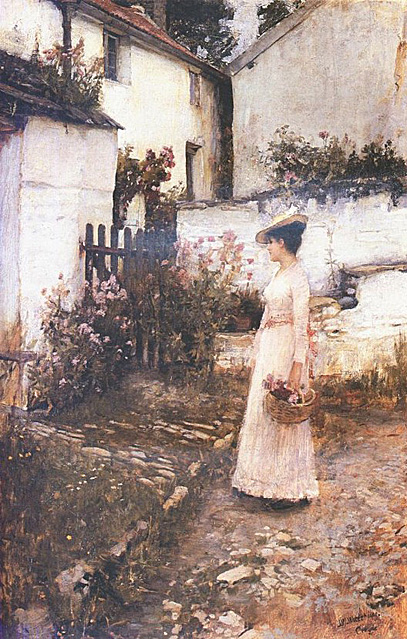

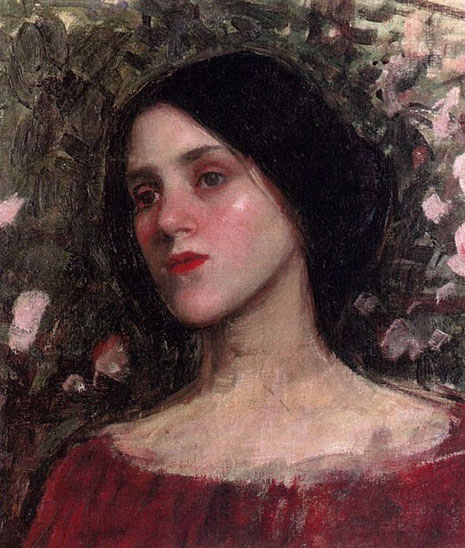

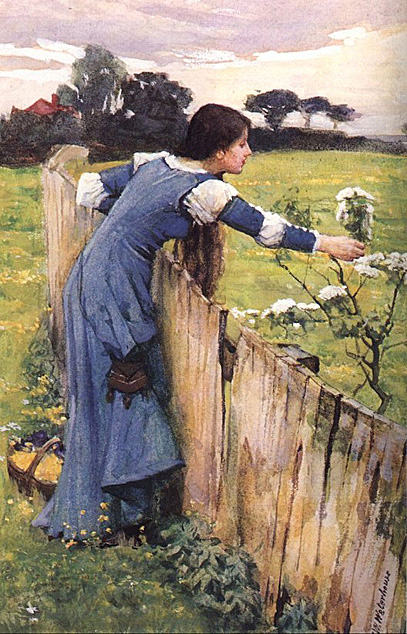

Celebrating the splendor of youth and the joys of spring, this important rediscovery was made by Odon Wagner. The work has never been exhibited in public and was reproduced only once during the artist's lifetime. The painting is signed and dated 1909 and has been established as the first picture in the Symbolist 'Persephone' series that engrossed Waterhouse from 1909 to 1914.

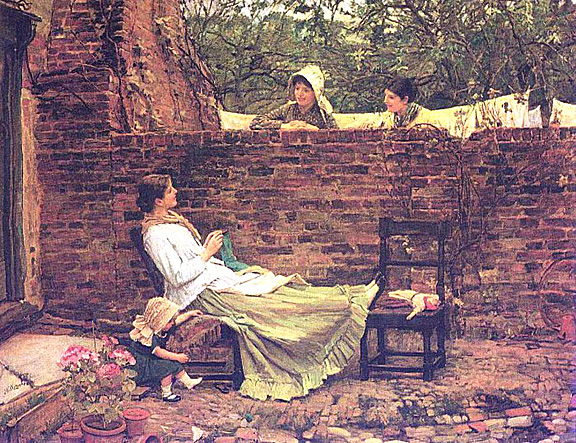

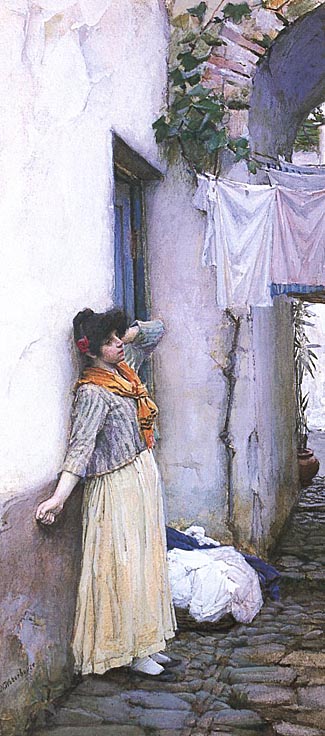

Waterhouse's sister-in-law Emily, married the landscape painter Peregrine Feeney, who built a house at Baggy Point, Croyde in Devon, after leaving Primrose Hill in 1892. The present picture can be dated between 1893 and 1910 when both Waterhouse and his wife, Esther, were frequent visitors to the cottage in Croyde. Few examples of his work from this period are in existence today.

The lady depicted in the rose filled garden may be the artist's wife. She bears a resemblance to the portrait of Esther that Waterhouse completed in 1894 which is now in the Sheffield City Art Gallery. It seems feasible that she may have posed for the picture on one of their visits to Devon, although the exact identity of the figure is difficult to ascertain from her features alone.

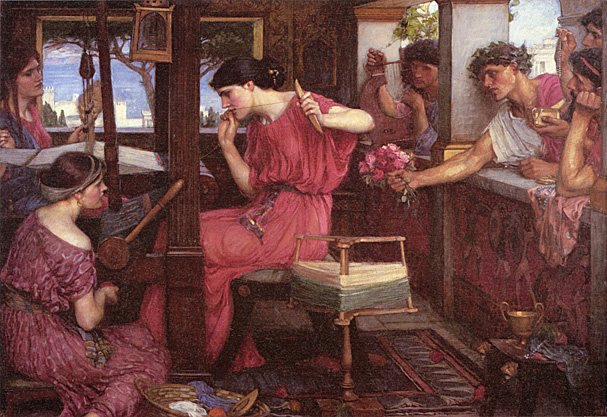

It illustrates the lines:

There she weaves by night and day

A magic web with colours gay.

She has heard a whisper say,

A curse is on her if she stay

To look down to Camelot.

She knows not what the curse may be,

And so she weaveth steadily,

And little other care hath she,

The Lady of Shalott.

It was this latter incarnation of Lamia as a beautiful woman that inspired John Keats to write his poem Lamia, published in 1820. Waterhouse bases his portrayal of Lamia upon Keats' poem:

She was a gordian shape of dazzling hue,

Vermilion-spotted, golden, green, and blue;

Striped like a zebra, freckled like a pard,

Eyed like a peacock, and all crimson barr'd;

And full of silver moons, that, as she breathed,

Dissolv'd, or brighter shone, or interwreathed

Their lustres with the gloomier tapestries--

So rainbow-sided, touch'd with miseries,

She seem'd, at once, some penanced lady elf,

Some demon's mistress, or the demon's self.

With one black shadow at its feet,

The house thro' all the level shines,

Close-latticed to the brooding heat,

And silent in its dusty vines:

A faint-blue ridge upon the right,

An empty river-bed before,

And shallows on a distant shore,

In glaring sand and inlets bright.

But 'Ave Mary,' made she moan,

And 'Ave Mary,' night and morn,

And 'Ah,' she sang, 'to be all alone,

To live forgotten, and love forlorn.'

She, as her carol sadder grew,

From brow and bosom slowly down

Thro' rosy taper fingers drew

Her streaming curls of deepest brown

To left and right, and made appear

Still-lighted in a secret shrine,

Her melancholy eyes divine,

The home of woe without a tear.

And 'Ave Mary,' was her moan,

'Madonna, sad is night and morn,'

And 'Ah,' she sang, 'to be all alone,

To live forgotten, and love forlorn.'

Till all the crimson changed, and past

Into deep orange o'er the sea,

Low on her knees herself she cast,

Before Our Lady murmur'd she;

Complaining, 'Mother, give me grace

To help me of my weary load.'

And on the liquid mirror glow'd

The clear perfection of her face.

'Is this the form,' she made her moan,

'That won his praises night and morn?'

And 'Ah,' she said, 'but I wake alone,

I sleep forgotten, I wake forlorn.'

Nor bird would sing, nor lamb would bleat,

Nor any cloud would cross the vault,

But day increased from heat to heat,

On stony drought and steaming salt;

Till now at noon she slept again,

And seem'd knee-deep in mountain grass,

And heard her native breezes pass,

And runlets babbling down the glen.

She breathed in sleep a lower moan,

And murmuring, as at night and morn,

She thought, 'My spirit is here alone,

Walks forgotten, and is forlorn.'

Dreaming, she knew it was a dream:

She felt he was and was not there.

She woke: the babble of the stream

Fell, and, without, the steady glare

Shrank one sick willow sere and small.

The river-bed was dusty-white;

And all the furnace of the light

Struck up against the blinding wall.

She whisper'd, with a stifled moan

More inward than at night or morn,

'Sweet Mother, let me not here alone

Live forgotten and die forlorn.'

And, rising, from her bosom drew

Old letters, breathing of her worth,

For 'Love,' they said, 'must needs be true,

To what is loveliest upon earth.'

An image seem'd to pass the door,

To look at her with slight, and say

'But now thy beauty flows away,

So be alone for evermore.'

'O cruel heart,' she changed her tone,

'And cruel love, whose end is scorn,

Is this the end to be left alone,

To live forgotten, and die forlorn?'

But sometimes in the falling day

An image seem'd to pass the door,

To look into her eyes and say,

'But thou shalt be alone no more.'

And flaming downward over all

From heat to heat the day decreased,

And slowly rounded to the east

The one black shadow from the wall.

'The day to night,' she made her moan,

'The day to night, the night to morn,

And day and night I am left alone

To live forgotten, and love forlorn.'

At eve a dry cicala sung,

There came a sound as of the sea;

Backward the lattice-blind she flung,

And lean'd upon the balcony.

There all in spaces rosy-bright

Large Hesper glitter'd on her tears,

And deepening thro' the silent spheres

Heaven over Heaven rose the night.

And weeping then she made her moan,

'The night comes on that knows not morn,

When I shall cease to be all alone,

To live forgotten, and love forlorn.'

Those cherries fairly do enclose

Of orient pearl a double row,

Which when her lovely laughter shows,

They look like rosebuds filled with snow.

Yet them nor peer nor prince can buy,

Till "Cherry-ripe" themselves do cry.

Her eyes like angels watch them still;

Her brows like bended bows do stand,

Threatening with piercing frowns to kill

All that attempt with eye or hand

Those sacred cherries to come nigh,

Till "Cherry-ripe" themselves do cry.

Thomas Campion

Orpheus joined the expedition of the Argonauts, saving them from the music of the Sirens by playing his own, more powerful music. On his return, he married Eurydice, who was soon killed by a snakebite. Overcome with grief, Orpheus ventured himself to the land of the dead to attempt to bring Eurydice back to life. With his singing and playing he charmed the ferryman Charon and the dog Cerberus, guardians of the River Styx. His music and grief so moved Hades, king of the underworld, that Orpheus was allowed to take Eurydice with him back to the world of life and light. Hades set one condition, however: upon leaving the land of death, both Orpheus and Eurydice were forbidden to look back. The couple climbed up toward the opening into the land of the living, and Orpheus, seeing the Sun again, turned back to share his delight with Eurydice. In that moment, she disappeared.

Orpheus himself was later killed by the women of Thrace. The motive and manner of his death vary in different accounts, but the earliest known, that of Aeschylus, says that they were Maenads urged by Dionysus to tear him to pieces in a Bacchic orgy because he preferred the worship of the rival god Apollo. His head, still singing, with his lyre, floated to Lesbos, where an oracle of Orpheus was established. The head prophesied until the oracle became more famous than that of Apollo at Delphi, at which time Apollo himself bade the Orphic oracle stop. The dismembered limbs of Orpheus were gathered up and buried by the Muses. His lyre they had placed in the heavens as a constellation.

This painting was auctioned at Sotheby's, London in November 2001. Prior to this auction this painting has only been known to us in black & white. Waterhouse kept the painting in his studio for his entire life and made several alterations to it over the years.

'The two figures recline side by side on a low couch, beyond which are the columns of a colonnade open to the night and touched with moonlight. The interior is lit by a lamp, whose light streams on the foremost figure, Sleep, whose head hangs in heavy stupor on his breast, and his right hand grasps some poppies. By his side lies Death in dusky shadow, with head thrown back, and the lines of the figure expressive of easeful lassitude. At his feet is an antique lyre, while immediately in the foreground is a low round table? The two figures are both young, and the beauty of youth belongs to one as much as to the other? the strange likeness and unlikeness of the recumbent figures.'

Prudentius says that the body of St Eulalia was shrouded by a miraculous fall of snow when lying exposed in the forum after her martyrdom.

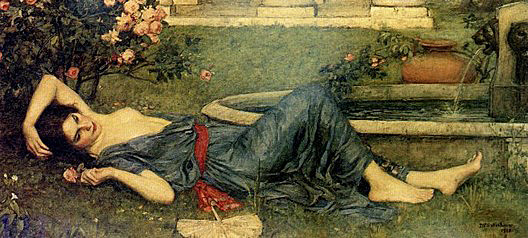

'This lovely painting of a girl lying on a lawn beside a pool is of the loosely classical but essentially subjectless type that John William Waterhouse, along with other Romantic artists of his generation, turned to in the early years of the present century. The ancient world is suggested to the spectator by the fountain - which consists of lion heads from the mouth of each of which a jet of water flows - and the marble pavement and column bases of a temple, seen at the top edge of the composition. Sweet Summer represents the ongoing Aesthetic tradition, pioneered by artists such as Edward Burne-Jones and Albert Moore in the 1860s. The senses are used to evoke the mood of the model. She is shown holding in her right hand a rose, the scent of which seems to pervade the scene; likewise the plash of water from the fountain fills the air with its gentle sound. Cast down on the grass is a fan, which indicates the warmth and oppressive stillness of a summer's day. In fact the heat is such that the girl has partially removed her dress, exposing her left arm and her breasts, and thus lending a sensuous character to the image. All of these elements of sight, sound and smell seem to contribute to a feeling of distraction and restlessness on the part of the girl, and as her gaze is far away and she is quite unconscious of the spectator, one must assume that the artist has sought to describe the emotions of unfulfilled love.

This picture was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1914: Summer Exhibition

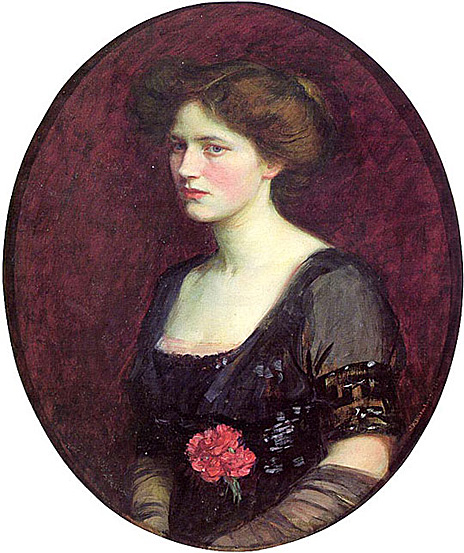

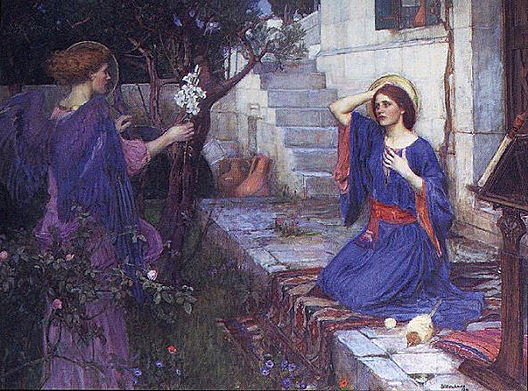

"Mr Waterhouse does himself full justice with his delicately treated Annunciation..." "It is certain however, from a drawing that this figure was studied from life. The composition of the picture divides it between nature (and super-nature) and architecture, and separates effectively the angel and the Virgin, whose figure is not surprisingly treated with skill and some imagination."

The central idea of the myth is that of the death and resurrection of Adonis, which represent the decay of nature every winter and its revival in spring. He is thus viewed by modern scholars as having originated as an ancient spirit of vegetation. Annual festivals called Adonia were held at Byblos and elsewhere to commemorate Adonis for the purpose of promoting the growth of vegetation and the falling of rain. The name Adonis is believed to be of Phoenician origin (from 'adon, "lord"), Adonis himself being identified with the Babylonian god Tammuz.

'He created this haven of warmth in the winter of his life, but almost unwittingly imbued it with a deeper meaning. Past the Dantesque guardian at the entrance, the snow is falling on the steps: it gathers on the entablature above the rounded Renaissance arches which evoke the Italy of his birth, and a few flakes are seen against the shadows of the arcade. But in the garden the roses bloom; one of the girls bends to inhale their scent, and the poppies presage a quiet oblivion. Roses and snow together sum up the duality of desire and restraint in all his work, and because poetry was ever-present in his life, he must also have had Tennyson's Arthur in mind, and 'the island-valley of Avilion, where falls not hail, or rain, or any snow. Nor ever wind blows loudly'.

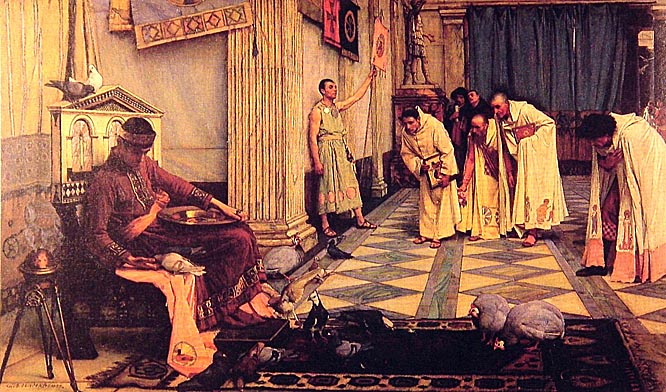

The 12th of January is dedicated to the Lares, the Roman household goddesses.

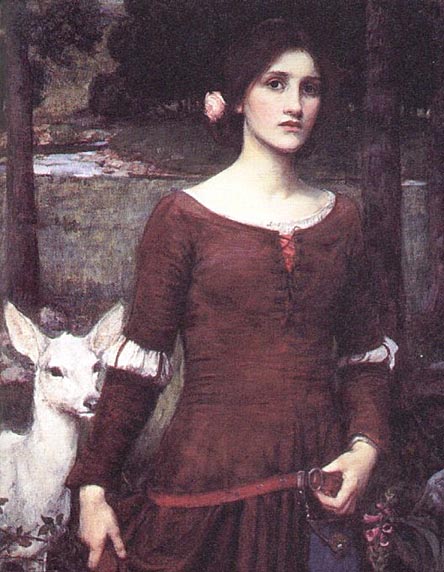

It was the time when lilies blow,

And clouds are highest up in air.

Lord Ronald brought a lily-white doe

To give his cousin, Lady Clare.

I trow they did not part in scorn:

Lovers long betrothed were they;

They two will wed the morrow morn;

God's blessing on the day!

"He does not love me for my birth

Nor for my lands so broad and fair;

He loves me for my own true worth,

And that is well," said Lady Clare.

In there came old Alice the nurse,

Said, "Who was this that went from thee?"

"It was my cousin," said Lady Clare;

"To-morrow he weds with me."

"Oh, God be thanked!" said Alice the nurse,

"That all comes round so just and fair:

Lord Ronald is heir of all your lands,

And you are not the Lady Clare."

"Are ye out of your mind, my nurse, my nurse,"

Said Lady Clare, "that ye speak so wild?"

"As God's above," said Alice the nurse,

"I speak the truth: you are my child.

The old earl's daughter died at my breast;

I speak the truth, as I live by bread!

I buried her like my own sweet child,

And put my child in her stead."

"Falsely, falsely have ye done,

O mother," she said, "if this be true,

To keep the best man under the sun

So many years from his due."

"Nay now, my child," said Alice the nurse,

"But keep the secret for your life,

And all you have will be Lord Ronald's,

When you are man and wife."

"If I'm a beggar born," she said

"I will speak out, for I dare not lie,

Pull off, pull off the brooch of gold,

And fling the diamond necklace by."

"Nay now, my child," said Alice the nurse,

"But keep the secret all you can."

She said, "Not so; but I will know

If there be any faith in man."

"Nay now, what faith?" said Alice the nurse,

"The man will cleave unto his right."

"And he shall have it," the lady replied,

"Though I should die to-night."

"Yet give one kiss to your mother, dear!

Alas, my child! I sinned for thee."

"O mother, mother, mother," she said,

"So strange it seems to me!

"Yet here's a kiss for my mother dear,

My mother dear, if this be so,

And lay your hand upon my head,

And bless me, mother, ere I go."

She clad herself in a russen gown,

She was no longer Lady Clare:

She went by dale, and she went by down,

With a single rose in her hair.

The lily-white doe Lord Ronald had brought

Leapt up from where she lay.

Dropped her head in the maiden's hand.

And followed her all the way.

Down stepped Lord Ronald from his tower:

"O Lady Clare, you shame your worth!

Why come you dressed like a village maid,

That are the flower of the earth?"

"If I come dressed like a village maid,

I am but as my fortunes are:

I am a begger born," she said,

"And not the Lady Clare."

"Play me no tricks," said Lord Ronald,

"For I am yours in word and in deed;

Play me no tricks," said Lord Ronald,

"Your riddle is hard to read."

Oh, and proudly stood she up!

Her heart within her did not fail:

She looked into Lord Ronald's eyes,

And told him all her nurse's tale.

He laughed a laugh of merry scorn:

He turned and kissed her where she stood;

"If you are not the heiress born,

And I," said he, "the next in blood--

"If you are not the heiress born,

And I," said he, "the lawful heir,

We two will wed to-morrow morn,

And you shall still be Lady Clare."

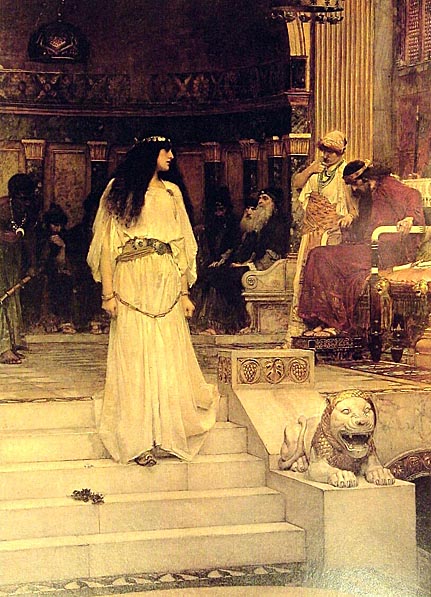

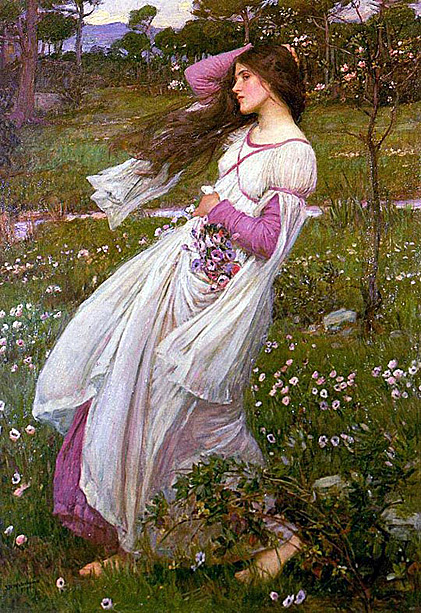

The painting illustrates lines from the poem The Lady of Shalott by Alfred Lord Tennyson:

"She left the web, she left the loom,

She made three paces thro' the room,

She saw the water-lily bloom,

She saw the helmet and the plume,

She look'd down to Camelot.

Out flew the web and floated wide;

The mirror crack'd from side to side;

"The curse is come upon me," cried

The Lady of Shalott."

A witch would cast a magic circle by turning clockwise, beginning at East, following the revolution of the sun. The magic circle was drawn with either a a magic wand or an anthame (a black-handled ceremonial dagger). A charm or spell was recited as the witch cast the circle, asking the presence of friendly or helpful spirits to attend."

Quoted from 'Witches: A Book of Magic and Wisdom'

'The sea-nymphs chant their accents shrill;

And the Sirens, taught to kill

With their sweet voice,

Make every echoing rock reply,

Unto their gentle murmuring noise'.

Thomas Campion (1567-1620), 'In Praise of Neptune'

A siren in Greek mythology was a creature half bird and half woman who lured sailors to destruction by the sweetness of her song. According to Homer there were two Sirens on an island in the western sea between Aeaea and the rocks of Scylla. Later the number was usually increased to three, and they were located on the west coast of Italy, near Naples. They were variously said to be the daughters of the sea god Phorcys or of the river god Achelous.

The Greek hero Odysseus (English: Ulysses), advised by the sorceress Circe, escaped the danger of their song by stopping the ears of his crew with wax so that they were deaf to the Sirens; yet he was able to hear the music and had himself tied to the mast so that he could not steer the ship out of course. Another story relates that when the Argonauts sailed that way, Orpheus sang so divinely that none of them listened to the Sirens. In later legend, after one or other of these failures the Sirens committed suicide. In art they appeared first as birds with the heads of women, later as women, sometimes winged, with bird legs.

The Sirens seem to have evolved from a primitive tale of the perils of early exploration combined with an Oriental image of a bird-woman. Anthropologists explain the Oriental image as a soul-bird--i.e., a winged ghost that stole the living to share its fate. In that respect the Sirens had affinities with the Harpies.

Waterhouse captures the two lovers together on the boat just before drinking the potion, thinking they are about to die. The desperation in Isolde's face can be clearly seen as she clutches the goblet with both hands. In Tristram we see a distinct look of resignation as he accepts it. Waterhouse also points out the separation that has been forced between them. They stand on either side of the painting with the cup and the bottle of potion between them. On Tristram's side lies his helmet and sword with a rope coiled underneath. In the background the castle can be seen illustrating a tie to his duty in bringing Isolde safely to the king. On Isolde's side sits a throne like chair symbolizing her duty to marry the king once she gets there. Also, there is a very distinct line representing a plank which runs between them, directly under the goblet, further emphasizing their separation. As Tristram accepts the cup his foot "steps over the line", foreshadowing that the separation between them is about to end.

Waterhouse painted a second version of this painting entitled Tristram and Isolde, which has the bottle of potion behind Tristram and less of the castle visible. There is also a crown on Isolde's head and a book which lies open at her feet. The edge of the plank separating the two is even more pronounced with Isolde actually appearing to be slightly elevated.

Waterhouse uses this myth to create an inspirational and compelling composition. The Sirens, as birds, flock around the ship singing with their melodic voices, the men gazing at them with awe. Ulysses himself, arms and legs tense, leans towards the mythical creatures with curious longing. The ship itself is beautifully designed with the oars protruding out of lions' heads on the sides, deep rich red sails, and its arching prow. On either side of the ship, the tall mountains force them down their path.

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.