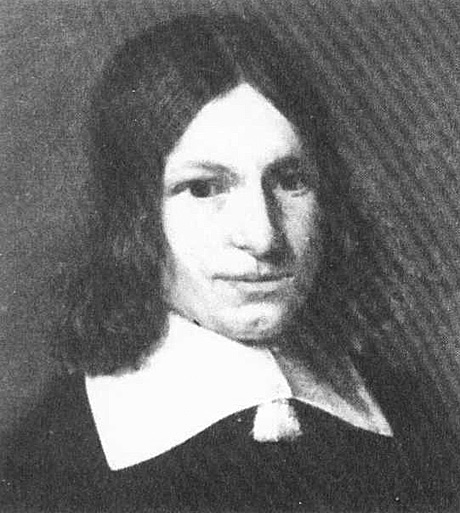

Dutch Baroque Painter and Draftsman

1629 - 1684

Senex Magister

aka 'The Hoocher Man

Pieter de Hooch, also spelled "Hoogh" or "Hooghe") was a genre painter during the Dutch Golden Age. He was a contemporary of Dutch Master Jan Vermeer, with whom his work shared themes and style.

De Hooch was born in Rotterdam to Hendrick Hendricksz de Hooch, a bricklayer, and Annetge Pieters, a midwife. He was the eldest of five children and outlived all of his siblings. He studied art in Haarlem under the landscape painter, Nicolaes Berchem. Beginning in 1650, he worked as a painter and servant for a linen-merchant and art collector named Justus de la Grange. His service for the merchant required him to accompany him on his travels to The Hague, Leiden, and Delft, to which he eventually moved. It is likely that de Hooch handed over most of his works to la Grange during this period in exchange for board and other benefits, as this was a common commercial arrangement for painters at the time, and a later inventory recorded that la Grange possessed eleven of his paintings.

De Hooch was married in Delft in 1654 to Jannetje van der Burch, by whom he fathered seven children. While in Delft, de Hooch is also believed to have learned from the painters Carel Fabritius and Nicolaes Maes, who were both early members of the Delft School. He became a member of the painters' guild of Saint Luke in 1655, and had moved to Amsterdam by 1661.

The early work of de Hooch, like most young painters of his time, was mostly composed of scenes of soldiers in stables and taverns, though he used these to develop great skill in light, color, and perspective rather than to explore an interest in the subject matter. After beginning his family in the mid-1650s, he switched his focus to domestic scenes and family portraits. His work showed astute observation of the mundane details of everyday life while also functioning as well-ordered morality tales. These paintings often exhibited a sophisticated and delicate treatment of light similar to those of Vermeer, who lived in Delft at the same time as de Hooch. Nineteenth Century art historians had assumed that Vermeer had been influenced by de Hooch's work, but the opposite is now believed.

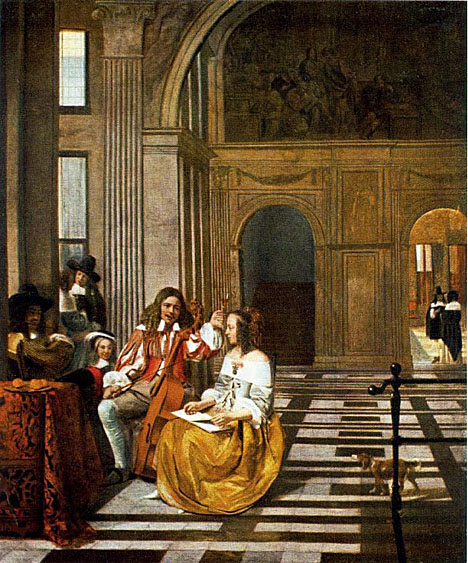

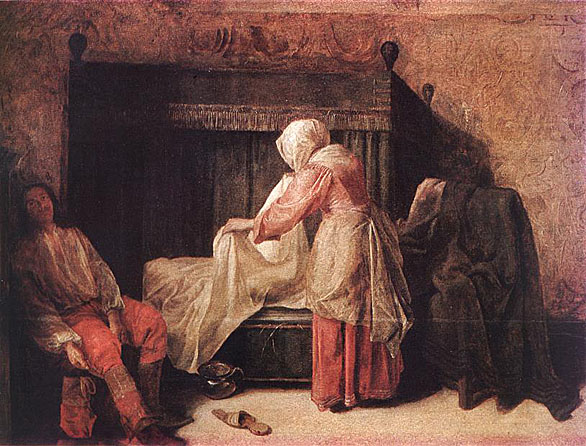

Though he began to paint for wealthier patrons in Amsterdam, he lived in the poorest areas of the city. Around this time, de Hooch's painting style became coarser and darker in color, and his simple domestic scenes were replaced by highly-decorated images set in palatial halls and country villas. Most scholars believe that de Hooch's work after around 1670 became more stylized and deteriorated in quality. It has been surmised that this was in part due to deteriorating health; de Hooch died in 1684 in an Amsterdam insane asylum, though how he came to be there is unrecorded.

When de Hooch moved to Amsterdam in I667 where he moved in high circles, his interiors became increasingly elegant, and his simple "households" were gradually replaced by palatial interiors. At the same time, the portrayal began to lose its precision and the vitality of the Dutch genre painting began to fade. His paintings also began to lose the strong color values so aptly described by Eugene Fromentin, a 19th century painter as follows: "The subtlety of Metsu and the enigma of Pieter de Hooch depend on there being much more air around the objects, shadow around the light, stability in volatile colours, blending of hues, pure invention in the portrayal of things, in a word: the most wonderful handling of light and shade there has ever been . . ."

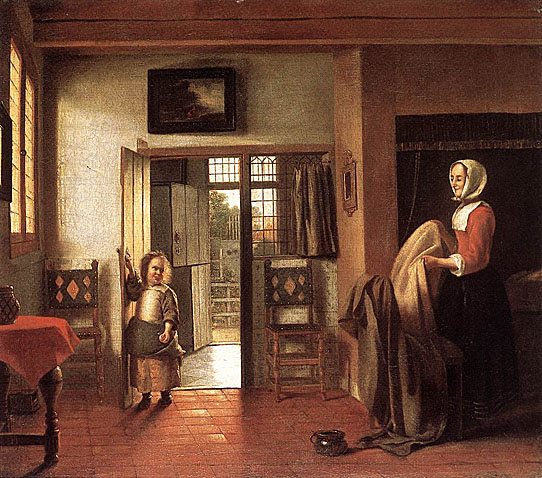

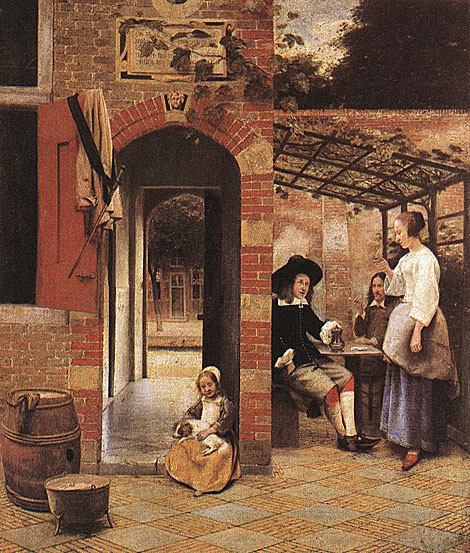

The earliest dated examples of De Hooch's Delft interiors are from 1658. He also painted a small number of closely related exterior scenes of which this painting, also from 1658, is the most outstanding example. It is unlikely to be a precisely accurate view as De Hooch used many of the same architectural elements in a second painting, also dated 1658, in which the right-hand side of the painting - where the maid and the child stand - was transformed to show a bower constructed with trellis-work beneath which two seated men and a standing woman drink and smoke. Both compositions are presumably based on quiet corners of Delft with which De Hooch was familiar. These and other paintings of De Hooch's Delft years evoke a world of quiet, domestic contentment, of pleasure taken in the performance of simple household tasks and in the appearance of well-ordered surroundings. It is an art which celebrates simple virtues, the efficient running of the home and the conscientious raising of children.

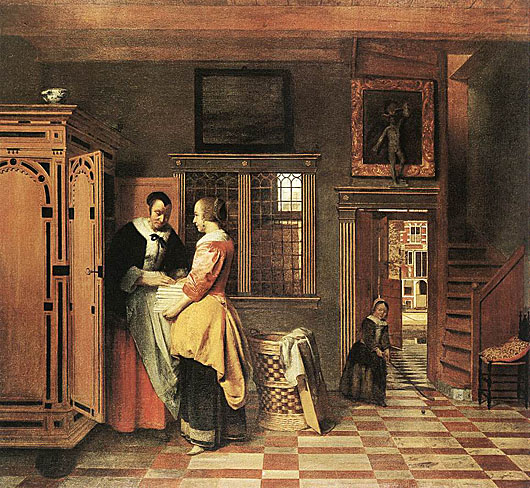

Here a classical statuette stands over the pilastered doorway and the woman and her maid take clean linen from an ornate 'kast' inlaid with ebony and surmounted by porcelain. In the background a child playfully wields a 'kolf' stick. Paintings such as these accurately show the details of Dutch interiors of the period and it is interesting to see a portrait in an elaborately carved gilt frame hanging alongside a landscape in a simple ebony frame. Through the open door, we can glimpse the buildings on the other side of the canal.

The sunlight streaming through the window suggests early afternoon. Reflected light and soft shadows are intermingled on the Oriental rug spread over the table, the leather-backed chairs, the curtain and the lead-framed window-panes. It seems as if the quiet would be hardly broken by any sounds from far or near. The act of reading by the young woman sitting in a corner of the room is just as objectively portrayed. The atmosphere of intimacy is absolute, emanating alike from the lady and the objects included in the composition.

This genre scene was painted in the artist's Amsterdam period but it has its origin in the interiors that De Hooch began to paint in Delft in the mid-1650's.

This painting shows some influence of the Rembrandt School, in the warmth and depth of the coloring, in the golden tonality, in the broad treatment of the figures, and in the impasto passage on the white fur. The intense reddish-orange of the woman's bodice, of the skirt hanging on the wall, and of the cradle cover are contrasted with the blue and grey in her coat, the bed curtain, the floor tiles, and the jug on the right.

De Hooch's use of the 'doorkijkje', the device also employed by Nicolaes Maes of opening the vista from one room to another, and then again from there into the street is not a mere play with perspective; in his paintings it adds a pictorial and psychological note of some significance. De Hooch sensed that in daily life one often experiences a pleasant relief when a relationship between indoor and outdoor space is established by the widened outlook and by the enrichment of light and atmosphere which it brings. In his refinement of the 'doorkijkje' device, as well as in other respects, de Hooch shows his own character.

These new developments in De Hooch's oeuvre were most probably inspired by local artists in Delft such as Carel Fabritius, Gerard Houckgeest and Emanuel de Witte, who were principally architectural painters interested in creating new illusionistic effects through the application of perspective. The View of Delft by Fabritius (National Gallery, London) stands as testimony to the form these early experiments took, just as A Lady at the Virginals by Vermeer shows the style brought to an unrivalled degree of perfection. De Hooch played a prominent part in the creation of the Delft school of painting. No earlier works had so successfully applied a cogent perspective system to the naturalistic representation of genre themes in secular spaces.

Several other paintings, also of outstanding quality, date from the same year as Card Players in a Sunlit Room including A Girl drinking with Two Soldiers (Paris, Louvre), A Soldier paying a Hostess (Marquess of Bute's collection) and The Courtyard of a House in Delft with a Woman and a Child (London, National Gallery). The mood of these pictures is calm and reflective, the actions of the figures restrained, and the rhythms languorous. There is a concentration on detail, as, for example, in the depiction of the playing cards, the raised glass and the broken pipe on the floor, in the lower right corner, which clearly absorbed the artist and enthralls the viewer. Such details help to create an atmosphere that is almost palpable in its freshness. The mother-of-pearl tone of the picture is enhanced by the use of pale colors against a grey ground, assisted by blending them with white.

The view through from the shadowy interior to the sunlit courtyard in the middle distance allows De Hooch to exploit his skill in the handling of light as it falls over the different surfaces. This is particularly apparent in the rendering of the translucent curtains and the panes of glass, as well as the way in which light helps to define the forms of the figures.

If the overall visual effect of the picture is one of a highly wrought finish, this is to some extent belied by the surprisingly broad handling of paint, particularly in the figures, and the almost matter-of-fact laying in of the squares on the tiled floor. Under-drawing is visible for the layout of the floor, and several compositional changes can be detected: for instance, the man drinking to the left of the group playing cards was originally given a hat. Unlike certain Dutch paintings of this type, De Hooch seems to have made no use of symbolism. The painting hung high on the wall on the right surely does not have a hidden meaning, but the broken pipe and the playing cards are perhaps open to interpretation.

The painting remained in Holland until the early nineteenth century. In 1823 the dealer, C. J. Nieuwenhuys, stated that 'its novelty awakened the attention of collectors both in France and England.' Two years later it is first recorded in England. Finally, it was acquired by Lord Farnborough for George IV in 1827.

Pieter de Hooch has gone down in art history as a painter who rendered Dutch domestic life with great precision. The private everyday life of the bourgeoisie in all its ordered tranquility, a world whose calm is never shattered by any sensational event, is the subject of his works. De Hooch opens a window on narrow alleyways, small gardens and courtyards, and gives us a glimpse into the antechambers and living-rooms of the Dutch citizens. Like Jan Vermeer, de Hooch specialized in the portrayal of interiors.

Yet, whereas the paintings of Vermeer tend to be dominated by a self-absorbed figure pausing momentarily in some activity, de Hooch's paintings are dominated by the room itself, by its perspectives and views through doors and windows where people become an integral part of the interior. Light is an important factor, especially daylight, as in the work of Vermeer, with its refractions and reflections adding vitality to the rooms. Whereas people and animals interpose in their activities, light itself becomes the active element, permeating and moving over walls, floors and tiles, illuminating objects or casting them in shadow.

Like Vermeer, de Hooch also draws upon religious paintings, translating them into scenes of everyday life. His painting of the housewife and her maid cleaning fish in a neat backyard, for example, recalls the topos of the Virgin Mary in the hortus conclusus. Rooms flooded with light take on aspects of the Annunciation or recall Jan van Eyck's Madonna in a Church Interior, lit by stained glass windows.

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.