O'Learys Visit Virgina - 2010

My sister's family paid a return visit to Virginia after first coming here in 2006 which delighted Bobbie and I (ad aspera). After Camping and White Water Rafting, we were on the route and I think a nice respite after enjoying all that Mother Nature is so apt at providing. It was also a time to enjoy and investigate some more history of which this area has in rich abundance. Bobbie enjoyed her role as tour guide while I protected the homefront but is always a joy to have the O'Leary's in our home.

We were on the last leg of their vacation time so they were ready to begin their sojourn here which would first take them to Harpers Ferry and the to Sharpsburg,and the Battle of Antietam.

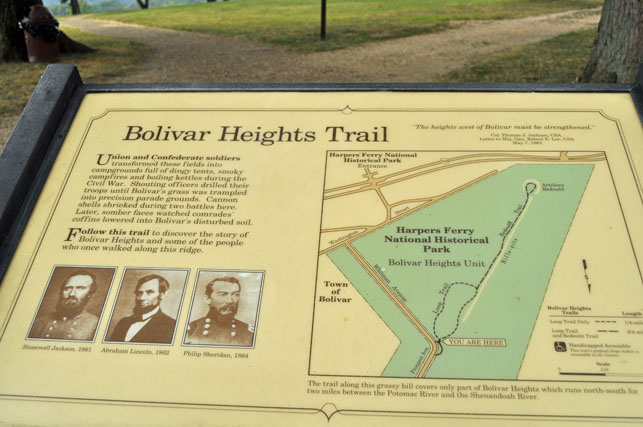

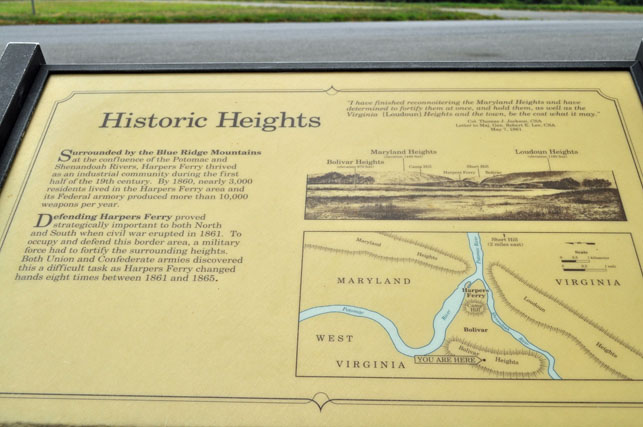

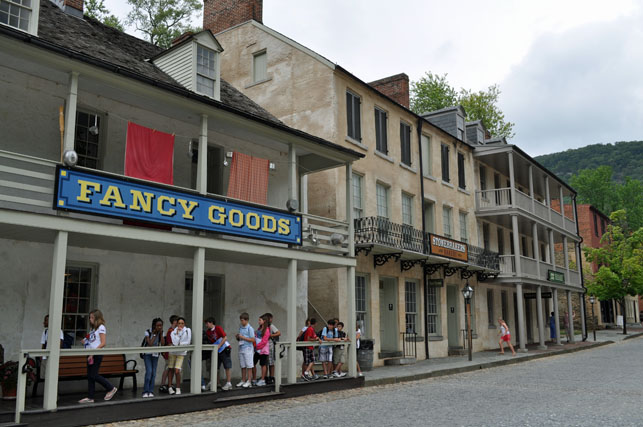

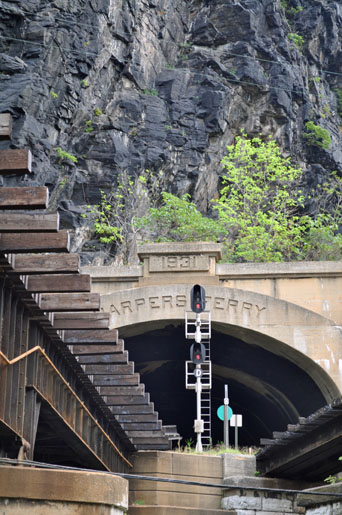

Harpers Ferry National Historical Park

After arriving at the Visitor's Center, Parks Service empoyees provide bus transportation into Historic Harpers Ferry.

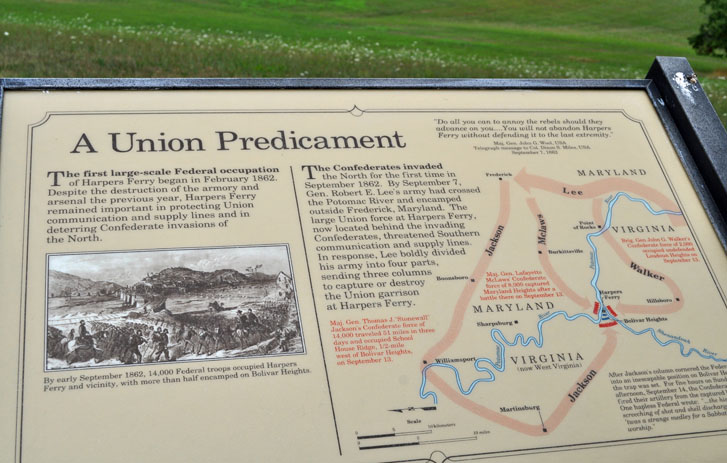

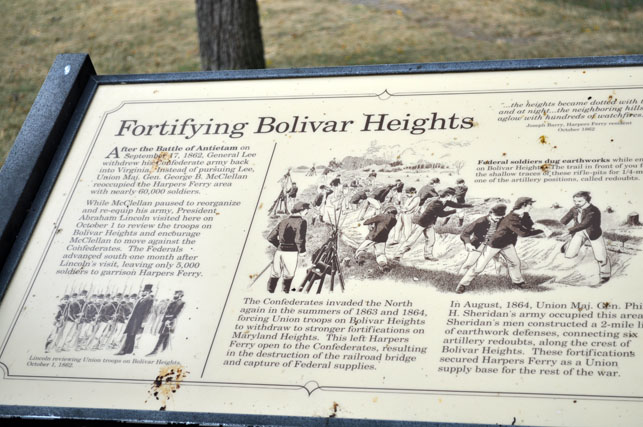

The Battle of Harpers Ferry was fought September 12-15, 1862, as part of the Maryland Campaign of the American Civil War. As General Robert E. Lee's Confederate Army invaded Maryland, a portion of his army under Major General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson surrounded, bombarded, and captured the Union garrison at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia), a major victory at relatively minor cost.

As Lee's Army of Northern Virginia advanced down the Shenandoah Valley into Maryland, he planned to capture the garrison and arsenal at Harpers Ferry, not only to seize its supplies of rifles and ammunition, but to secure his line of supply back to Virginia. Although he was being pursued at a leisurely pace by Major General George B. McClellan's Army of the Potomac, outnumbering him more than two to one, Lee chose the risky strategy of dividing his army and sent one portion to converge and attack Harpers Ferry from three directions. Colonel Dixon S. Miles, Union commander at Harpers Ferry, insisted on keeping most of the troops near the town instead of taking up commanding positions on the surrounding heights. The slim defenses of the most important position, Maryland Heights, first encountered the approaching Confederate on September 12, but only brief skirmishing ensued. Strong attacks by two Confederate brigades on September 13 drove the Union troops from the heights.

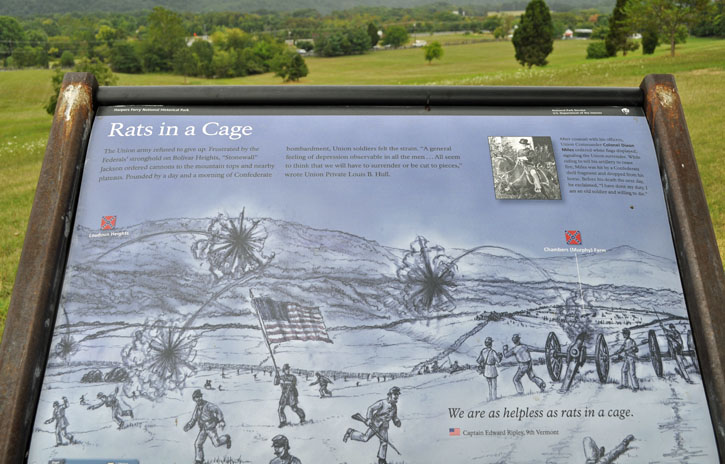

During the fighting on Maryland Heights, the other Confederate columns arrived and were astonished to see that critical positions to the west and south of town were not defended. Jackson methodically positioned his artillery around Harpers Ferry and ordered Major General A.P. Hill to move down the west bank of the Shenandoah River in preparation for a flank attack on the Federal left the next morning. By the morning of September 15, Jackson had positioned nearly 50 guns on Maryland Heights and at the base of Loudoun Heights. He began a fierce artillery barrage from all sides and ordered an infantry assault. Miles realized that the situation was hopeless and agreed with his subordinates to raise the white flag of surrender. Before he could surrender personally, he was mortally wounded by an artillery shell and died the next day. After processing more than 12,000 Union prisoners, Jackson's men then rushed to Sharpsburg, Maryland, to rejoin Lee for the Battle of Antietam.

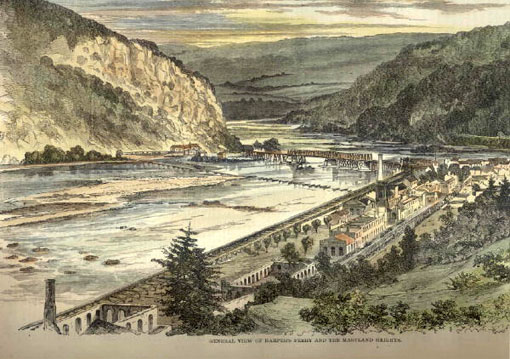

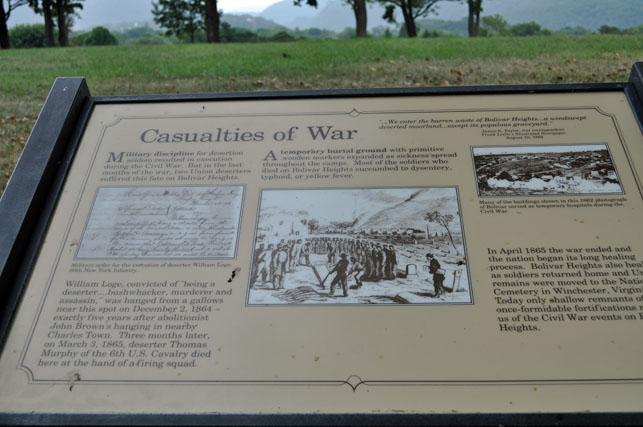

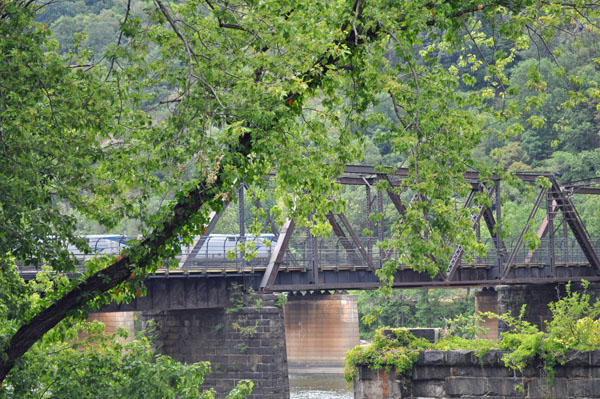

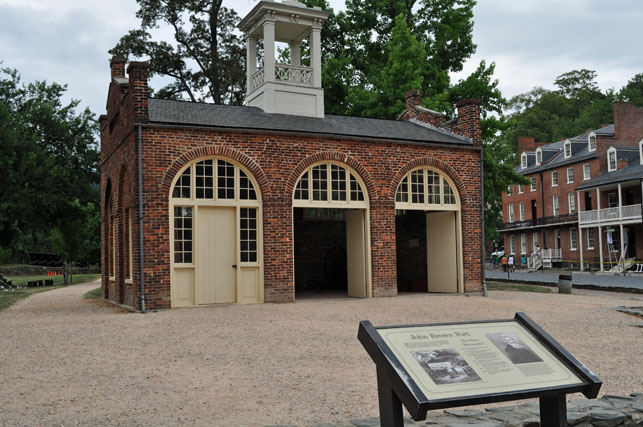

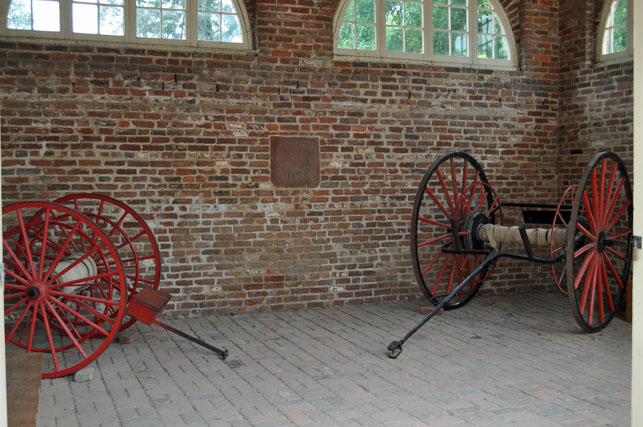

Harpers Ferry (originally Harper's Ferry) is a small town at the confluence of the Potomac River and the Shenandoah River, the site of a historic Federal arsenal (founded by President George Washington in 1799) and a bridge for the critical Baltimore and Ohio Railroad across the Potomac. It was earlier the site of the abolitionist John Brown's attack on the Federal arsenal there in 1859.

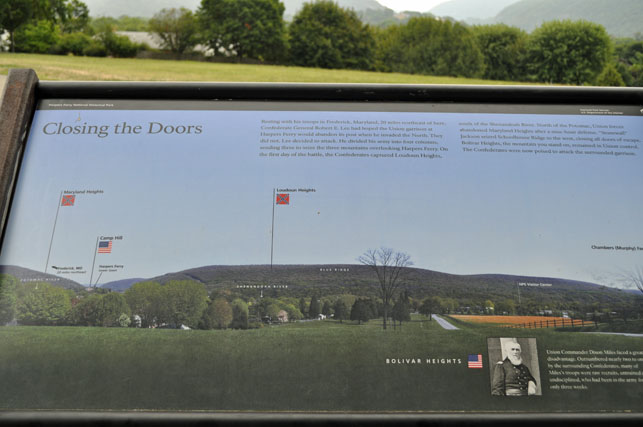

The town was virtually indefensible, dominated on all sides by higher ground. To the west, the ground rose gradually for about a mile and a half to Bolivar Heights, a plateau 668 feet high, that stretches from the Potomac to the Shenandoah. To the south, across the Shenandoah, Loudoun Heights overlooks from 1,180 feet. And to the northeast, across the Potomac, the southernmost extremity of Elk Ridge forms the 1,476-foot-high crest of Maryland Heights. A Federal soldier wrote that if these three heights could not be held, Harpers Ferry would be "no more defensible than a well bottom."

As General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia advanced into Maryland, Lee expected that the Union garrisons that potentially blocked his supply line in the Shenandoah Valley, at Winchester, Martinsburg, and Harpers Ferry, would be cut off and abandoned without firing a shot (and, in fact, both Winchester and Martinsburg were evacuated). But the Harpers Ferry garrison had not retreated. Lee planned to capture the garrison and the arsenal, not only to seize its supplies of rifles and ammunition, but to secure his line of supply back to Virginia.

Although he was being pursued at a leisurely pace by Major General George B. McClellan and the Union Army of the Potomac, outnumbering him more than two to one, Lee chose the risky strategy of dividing his army to seize the prize of Harpers Ferry. While the corps of Major General James Longstreet drove north in the direction of Hagerstown, Lee sent columns of troops to converge and attack Harpers Ferry from three directions. The largest column, 11,500 men under Jackson, was to re-cross the Potomac and circle around to the west of Harpers Ferry and attack it from Bolivar Heights, while the other two columns, under Major General Lafayette McLaws (8,000 men) and Brigadier Gen. John G. Walker (3,400), were to capture Maryland Heights and Loudoun Heights, commanding the town from the east and south.

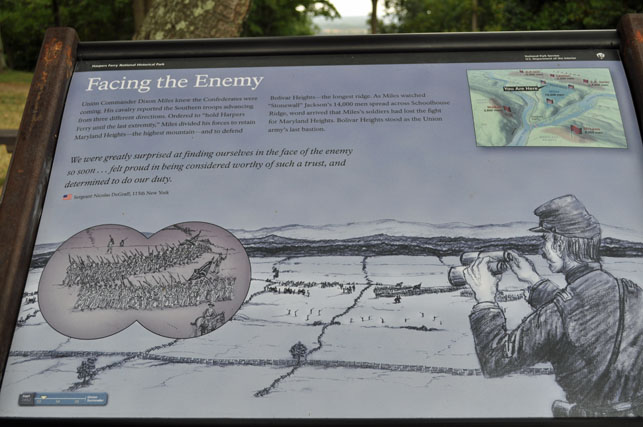

McClellan had wanted to add the Harpers Ferry garrison to his field army, but general-in-chief Henry W. Halleck had refused, saying that the movement would be too difficult and that the garrison had to defend itself "until the latest moment," or until McClellan could relieve it. Halleck had probably expected its commander, Colonel Dixon S. Miles, to show some military knowledge and courage. Miles was a 38-year veteran of the U.S. Army and the Mexican-American War, but who had been disgraced after the First Battle of Bull Run when a court of inquiry held that he had been drunk during the battle. Miles swore off liquor and was sent to the supposedly quiet post at Harpers Ferry. His garrison comprised 14,000 men, many inexperienced, including 2,500 who had been forced out of Martinsburg by the approach of Jackson's men on September 11.

On the night of September 11, McLaws arrived at Brownsville, 6 miles northeast of Harpers Ferry. He left 3,000 men near Brownsville Gap to protect his rear and moved 3,000 others toward the Potomac River to seal off any eastern escape route from Harpers Ferry. He dispatched the veteran brigades of Brigadier Generals Joseph B. Kershaw and William Barksdale to seize Maryland Heights on September 12. The other Confederate columns were making slow progress and were behind schedule. Jackson's men were delayed at Martinsburg. Walker's men were ordered to destroy the aqueduct carrying the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal across the Monocacy River where it empties into the Potomac, but his engineers had difficulty demolishing the stone structure and the attempt was eventually abandoned.

Walker reentered Virginia, in Loudoun County on the 9th, across from Point of Rocks. Walker was escorted by Colonel E.V. White, Loudoun native, and his 35th Battalion of Virginia Cavalry. White was unhappy with the assignment and preferred to be with the rest of the army. Unfortunately White had gotten into an altercation with Major General J.E.B. Stuart in Frederick and was subsequently ordered back to Virginia by Lee. Whether or not his disposition was to blame, White led Walker on a meandering route around the Short Hill Mountain to reach the base of Loudoun Heights four days later on September 13. So the attack on Harpers Ferry that had been planned for September 11 was delayed, increasing the risk that McClellan might engage and destroy a portion of Lee's army while it was divided.

Miles insisted on keeping most of the troops near the town instead of taking up commanding positions on the surrounding heights. He apparently was interpreting literally his orders to hold the town. The defenses of the most important position, Maryland Heights, were designed to fight off raiders, but not to hold the heights themselves. There was a powerful artillery battery halfway up the heights: two 9-inch naval Dahlgren rifles, one 50-pounder Parrott rifle, and four 12-pounder smoothbores. On the crest, Miles assigned Colonel Thomas H. Ford of the 32nd Ohio Infantry to command parts of four regiments, 1,600 men. Some of these men, including those of the 126th New York, had been in the Army only 21 days and lacked basic combat skills. They erected primitive breastworks and sent skirmishers a quarter-mile in the direction of the Confederates. On September 12 they encountered the approaching men from Kershaw's South Carolina brigade, who had been moving slowly through the very difficult terrain on Elk Ridge. Rifle volleys from behind abatis caused the Confederates to stop for the night.

Kershaw began his attack at about 6:30 a.m., September 13. He planned to push his own brigade directly against the Union breastworks while Barksdale's Mississippians flanked the Federal right. Kershaw's men charged into the abatis twice and were driven back with heavy losses. The inexperienced New York troops were holding their own. Their commander, Colonel Ford, felt ill that morning and stayed back two miles behind the lines, leaving the fighting to Colonel Eliakim Sherrill, the second-ranking officer. Sherrill was wounded by a bullet through the cheek and tongue while rallying his men and had to be carried from the field, making the green troops grow panicky. As Barksdale's Mississippians approached on the flank, the New Yorkers broke and fled rearward. Although Major Sylvester Hewitt ordered the remaining units to reform farther along the ridge, orders came at 3:30 p.m. from Colonel Ford to retreat. (In doing so, he apparently neglected to send for the 900 men of the 115th New York, waiting in reserve midway up the slope.) His men destroyed their artillery pieces and crossed a pontoon bridge back to Harpers Ferry. Ford later insisted he had the authority from Miles to order the withdrawal, but a court of inquiry concluded that he had "abandoned his position without sufficient cause," and recommended his dismissal from the Army.

During the fighting on Maryland Heights, the other Confederate columns arrived - Walker to the base of Loudoun Heights at 10 a.m. and Jackson's three divisions (Brigadier Genweal John R. Jones to the north, Brigadier General Alexander R. Lawton in the center, and Major General A.P. Hill to the south) to the west of Bolivar Heights at 11 AM - and were astonished to see that these positions were not defended. Inside the town, the Union officers realized they were surrounded and pleaded with Miles to attempt to recapture Maryland Heights, but he refused, insisting that his forces on Bolivar Heights would defend the town from the west. He exclaimed, "I am ordered to hold this place and God damn my soul to hell if I don't." In fact, Jackson's and Miles's forces to the west of town were roughly equal, but Miles was ignoring the threat from the artillery massing to his northeast and south.

Late that night, Miles sent Captain Charles Russell of the 1st Maryland Cavalry with nine troopers to slip through the enemy lines and take a message to McClellan, or any other general he could find, informing them that the besieged town could hold out only for 48 hours. Otherwise, he would be forced to surrender. Russell's men slipped across South Mountain and reached McClellan's headquarters at Frederick. The general was surprised and dismayed to receive the news. He wrote a message to Miles that a relief force was on the way and told him, "Hold out to the last extremity. If it is possible, re-occupy the Maryland Heights with your whole force." McClellan ordered Major General William B. Franklin and his VI Corps to march from Crampton's Gap to relieve Miles. Although three couriers were sent with this information on different routes, none of them reached Harpers Ferry in time.

While battles raged at the passes on South Mountain, Jackson had methodically positioned his artillery around Harpers Ferry. This included four Parrott rifles to the summit of Maryland Heights, a task that required 200 men wrestling the ropes of each gun. Although Jackson wanted all of his guns to open fire simultaneously, Walker on Loudoun Heights grew impatient and began an ineffectual bombardment with five guns shortly after 1 PM. Jackson ordered A.P. Hill to move down the west bank of the Shenandoah in preparation for a flank attack on the Federal left the next morning.

That night, the Union officers realized they had less than 24 hours left, but they made no attempt to recapture Maryland Heights. Unbeknownst to Miles, only a single Confederate Regiment now occupied the crest, after McLaws had withdrawn the remainder to meet the Union assault at Crampton's Gap.

Colonel Benjamin F. "Grimes" Davis proposed to Miles that his troopers of the 12th Illinois Cavalry, the Loudoun Rangers, and some smaller units from Maryland and Rhode Island, attempt to break out. Cavalry forces were essentially useless in the defense of the town. Miles dismissed the idea as "wild and impractical," but Davis was adamant and Miles relented when he saw that the fiery Mississippian intended to break out, with or without permission. Davis and Colonel Amos Voss led their 1,400 cavalrymen out of Harpers Ferry on a pontoon bridge across the Potomac, turning left onto a narrow road that wound to the west around the base of Maryland Heights in the north toward Sharpsburg. Despite a number of close calls with returning Confederates from South Mountain, the cavalry column encountered a wagon train approaching from Hagerstown with James Longstreet's reserve supply of ammunition. They were able to trick the wagoneers into following them in another direction and they repulsed the Confederate cavalry escort in the rear of the column. Capturing more than 40 enemy ordnance wagons, Davis had lost not a single man in combat, the first great cavalry exploit of the war for the Army of the Potomac.

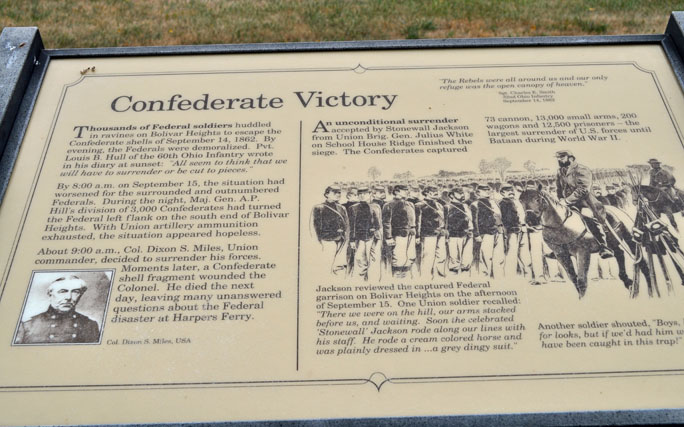

By the morning of September 15, Jackson had positioned nearly 50 guns on Maryland Heights and at the base of Loudoun Heights, prepared to enfilade the rear of the Federal line on Bolivar Heights. Jackson began a fierce artillery barrage from all sides and ordered an infantry assault for 8 a.m. Miles realized that the situation was hopeless. He had no expectation that relief would arrive from McClellan in time and his artillery ammunition was in short supply. At a council of war with his brigade commanders, he agreed to raise the white flag of surrender. But he would not be personally present at any ceremony. He was confronted by a captain of the 126th New York Infantry, who said, "For Christ's sake, Colonel, don't surrender us. Don't you hear the signal guns? Our forces are near us. Let us cut our way out and join them." But Miles replied, "Impossible. They will blow us out of this place in half an hour." As the captain turned away in disdain, a shell exploded, shattering Miles's left leg. So disgusted were the men of the garrison with Miles's behavior, which some claimed involved being drunk again, it was difficult to find a man who would take him to the hospital. He was mortally wounded and died the next day. Some historians have speculated that Miles was struck deliberately by fire from his own men.

Jackson had won a great victory at minor expense. The Confederate Army sustained 286 casualties (39 killed, 247 wounded), mostly from the fighting on Maryland Heights, while the Union Army sustained 217 (44 killed, 173 wounded). The Union garrison also surrendered 12,419 men, 13,000 small arms, 200 wagons, and 73 artillery pieces. It was the largest surrender of Federal forces during the Civil War.

Confederate soldiers feasted on Union food supplies and helped themselves to fresh blue Federal uniforms, which would cause some confusion in the coming days. About the only unhappy men in Jackson's force were the cavalrymen, who had hoped to replenish their exhausted mounts.

Jackson sent off a courier to Lee with the news. "Through God's blessing, Harper's Ferry and its garrison are to be surrendered." As he rode into town to supervise his men, Union soldiers lined the roadside, eager for a look at the famous Stonewall. One of them observed Jackson's dirty, seedy uniform and remarked, "Boys, he isn't much for looks, but if we'd had him we wouldn't have been caught in this trap." By early afternoon, Jackson received an urgent message from General Lee: Get your troops to Sharpsburg as quickly as possible. Jackson left A.P. Hill at Harpers Ferry to manage the parole of Federal prisoners and began marching to join the Battle of Antietam.

Quoted From: Battle of Harpers Ferry - Wikipedia

Chesapeake and Ohio Canal - Wikipedia

Abandoned Maryland: the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal - SkyscraperCity

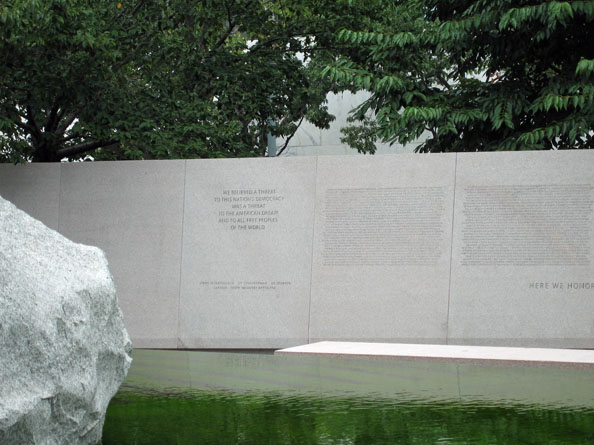

New York State Monument

Excelsior

The State of New York in commemoration of the Services of its officers and soldiers in

the Battle of Antietam, Sept. 17, 1862

Record of New York State at Antietam

67 Regiments of Infantry

5 Regiments of Cavalry

14 Batteries of Artillery

2 Regiments of Engineers

New York's losses on this field were 65 officers and 624 enlisted men killed or mortally

wounded; 110 officers and 2687 enlisted men wounded and 2 officers and 277 men

captured or missing, making a total of 3765.

Erected A. D. 1919

Under the auspices of the New York Monument Commission Co. Lewis R. Stegman,

Chairman; Col. Clinton Beckwith, Charles A. Shaw, U.S.C.; Brig. Gen. Charles W. Berry,

Adj. Gen. S.N.Y.

Quoted From: Antietam National Battlefield - New York State Monument (U.S. National Park Service)

Maryland State Monument

Ohio Monument

These three regiments became engaged about 7:30 A.M., September 17, 1862, advanced

and drove the enemy from the woods near the Dunkard Church and were in action until

1:30 P.M. Their combined loss was 17 men killed, 4 officers and 87 men wounded,

2 men missing, total 110.

5th Infantry

Commanded by

Major John Collins

7th Infantry

Commanded by

Col. Eugene Powell

66th Infantry

Commanded by

Lieut. Major Orrin J. Crane

Tyndale's (1st) Brigade

Greene's (2d) Division

Twelfth Army Corps Army of the Potomac

5th 66th 7th

Quoted From: Antietam National Battlefield - 5th, 7th, and 66th Ohio Infantry Monument (U.S. National Park Service)

The Dunker Church

The Battle of Antietam, fought September 17, 1862, was one of the bloodiest battles in the history of this nation. Yet, one of the most noted landmarks on this great field of combat is a house of worship associated with peace and love. Indeed, the Dunker Church ranks as perhaps one of the most famous churches in American military history. This historic structure began as a humble country house of worship constructed by local Dunker farmers in 1852. It was Mr. Samuel Mumma, owner of the nearby farm that bears his name, that donated land in 1851 for the Dunkers to build their church. During its early history the congregation consisted of about half a dozen-farm families from the local area.

On the eve of the Battle of Antietam, the members of the Dunker congregation, as well as their neighbors in the surrounding community, received a portent of things to come. That Sunday, September 14, 1862, the sound of cannons booming at the Battle of South Mountain seven miles to the east was plainly heard as the Dunkers attended church. By September 16 Confederate infantry and artillery was being positioned around the church in anticipation of the battle that was fought the next day.

During the battle of Antietam the church was the focal point of a number of Union attacks against the Confederate left flank. Most after action reports by commanders of both sides, including Union General Hooker and Confederate Stonewall Jackson, make references to the church.

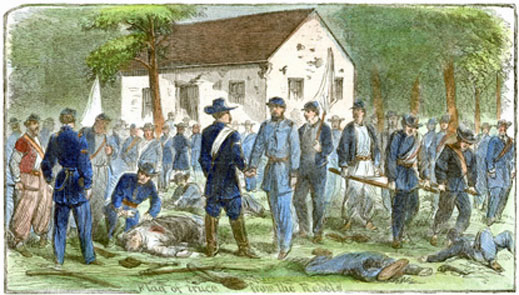

At battles end the Confederates used the church as a temporary medical aid station. A sketch by well known Civil War artist Alfred Waud depicts a truce between the opposing sides being held in front of the church on September 18, in order to exchange wounded and bury the dead. At least one account states that after the battle the Union Army used the Dunker Church as an embalming station. One tradition persists that Lincoln may have visited the site during his visit to the Army of the Potomac in October 1862.

As for the old church, it was heavily battle scarred with hundreds of marks from bullets in its white washed walls. Likewise artillery had rendered serious damage to the roof and walls. By 1864 the Church was repaired, rededicated and regular services were held there until the turn of the century.

Quoted From: Antietam National Battlefield - The Dunker Church at Antietam (U.S. National Park Service)

"The Lost Order"

From

"Manassas to Appomattox" By James Longstreet

THE strange losing and stranger finding of Lee's "General Order No. 191," commonly referred to as "the lost dispatch," which he had issued September 9 for the movement of his army, made a difference in our Maryland campaign for better or for worse.

Before this tell-tale slip of paper found its way to McClellan's head-quarters he was well advised by his cavalry, and by dispatches wired him from east and west, of the movements of Lee's army, and later, on that eventful 13th day of September, he received more valuable information, even to a complete revelation of his adversary's plans and purpose, such as no other commander, in the history of war, has had at a time so momentous. So well satisfied was he that he was master of the military zodiac that he dispatched the Washington authorities of Lee's "gross mistake" and exposure to severe penalties. There was not a point upon which he wanted further information nor a plea for a moment of delay. His army was moving rapidly; all that he wished for was that the plans of the enemy would not be changed. The only change that occurred in the plans was the delay of their execution, which worked to his greater advantage. By following the operations of the armies through the complications of the campaign we may form better judgment of the work of the commanders in finding ways through its intricacies: of the efforts of one to grasp the envied crown so haplessly tendered; of the other in seeking refuge that might cover catastrophe involved in the complexity of misconceived plans.

The copy of the order that was lost was sent by General Jackson to General D. H. Hill under the impression that Hill's division was part of his command, but the division had not been so assigned, and that copy of the order was not delivered at Hill's headquarters, but had been put to other use. The order sent to General Hill from general headquarters was carefully preserved.

When the Federals marched into Frederick, just left by the Confederates, General Sumner's column went into camp about noon, and it was then that the dispatch was found by Colonel Silas Colgrove, who took it to division head-quarters, whence it was quickly sent to the Federal commander.

General McClellan reported to General Halleck that the lost order had been handed him in the evening, but it is evident that he had it at the time of his noonday dispatch to the President, from his reference to the facts it exposed.

It is possible that it was at first suspected as a ruse de guerre, and that a little time was necessary to convince McClellan of its genuineness, which may account for the difference between the hinted information in his dispatch to General Halleck and the confident statement made at noonday to the President.

Some of the Confederates were a little surprised that a matter of such magnitude was entrusted to pen-and-ink dispatches. The copy sent me was carefully read, then used as some persons use a little cut of tobacco, to be assured that others could not have the benefit of its contents.

It has been in evidence that the copy that was lost had been used as a wrapper for three fragrant Confederate cigars in the interim between its importance when issued by the Confederate Chief and its greater importance when found by the Federals.

General Halleck thought the capital in imminent peril before he heard from McClellan on the 13th, as shown on that day by a dispatch to General McClellan:

"The capture of this place will throw us back six months, if it should not destroy us."

But later, the" lost dispatch" having turned up at head-quarters of General McClellan, that commander apprised the authorities of the true condition of affairs in the following:

TO THE PRESIDENT:

I have the whole rebel force in front of me, but am confident, and no time shall be lost. I have a difficult task to perform, but with God's blessing will accomplish it. I think Lee has made a gross mistake, and that he will be severely punished for it. The army is in motion as rapidly as possible. I hope for a great success if the plans of the rebels remain unchanged. We have possession of Catoctin. I have all the plans of the rebels, and will catch them in their own trap if my men are equal to the emergency. I now feel that I can count on them as of old. All forces of Pennsylvania should be placed to co-operate at Chambersburg. My respects to Mrs. Lincoln. Received most enthusiastically by the ladies. Will send you trophies. All well, and with God's blessing will accomplish it.

GEORGE B. MCCLELLAN

MAJOR-GENERAL H. W. HALLECK,

General-in-Chief:

An order from General R. E. Lee, addressed to General D. H. Hill, which has accidentally come into my hands this evening,--the authenticity of which is unquestionable,--discloses some of the plans of the enemy, and shows most conclusively that the main rebel army is now before us, including Longstreet's, Jackson's, the two Hills's, McLaws's, Walker's, R. H. Anderson's, and Hood's commands. That army was ordered to march on the 10th, and to attack and capture our forces at Harper's Ferry and Martinsburg yesterday, by surrounding them with such a heavy force that they conceived it impossible they could escape. They were also ordered to take possession of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad; afterwards to concentrate again at Boonsborough or Hagerstown. That this was the plan of campaign on the 9th is confirmed by the fact that heavy firing has been heard in the direction of Harper's Ferry this afternoon, and the columns took the roads specified in the order. It may, therefore, in my judgment, be regarded as certain that this rebel army, which I have good reasons for believing amounts to 120,000 men or more, and know to be commanded by Lee in person, intended to attempt penetrating Pennsylvania. The officers told their friends here that they were going to Harrisburg and Philadelphia. My advance has pushed forward to-day and overtaken the enemy on the Middletown and Harper's Ferry roads, and several slight engagements have taken place, in which our troops have driven the enemy from their position. A train of wagons, about three-quarters of a mile long, was destroyed to-day by the rebels in their flight. We took over fifty prisoners. This army marches forward early to-morrow morning, and will make forced marches, to endeavor to relieve Colonel Miles, but I fear, unless he makes a stout resistance, we may be too late.

A report came in just this moment that Miles was attacked to-day, and repulsed the enemy, but I do not know what credit to attach to the statement. I shall do everything in my power to save Miles if he still holds out. Portions of Burnside's and Franklin's corps move forward this evening.

I have received your dispatch of ten A.M. You will perceive, from what I have stated, that there is but little probability of the enemy being in much force south of the Potomac. I do not, by any means, wish to be understood as undervaluing the importance of holding Washington. It is of great consequence, but upon the success of this army the fate of the nation depends. It was for this reason that I said everything else should be made subordinate to placing this army in proper condition to meet the large rebel force in our front. Unless General Lee has changed his plans, I expect a severe general engagement to-morrow. I feel confident that there is now no rebel force immediately threatening Washington or Baltimore, but that I have the mass of their troops to contend with, and they outnumber me when united.

GEORGE B. MCCLELLAN,

Major-General

Quoted From: The Lost Order, S.O. 191

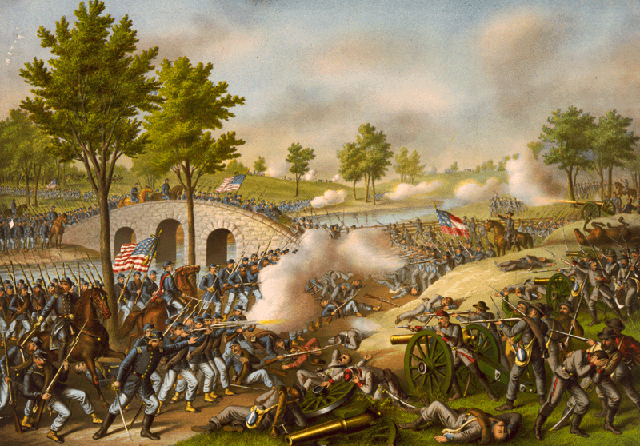

The Battle began at dawn on September 17, 1862, when Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker began the Union artillery bombardment off the Confederate positions of Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson positions in the Miller cornfield. Hooker's troops advanced behind the falling shells and drove the Confederates from their positions. Around 7 a.m. Jackson reinforced his troops and pushed the Union troops back. Union Major General Joseph K. Mansfield sent his men into the fray and regained some of the ground lost to the Confederates.

Historic Fencing

The battlefield is currently restoring miles of historic fences that existed at the time of

the battle. Using historic maps and photographs, park staff and volunteers have built

two main types of fences - five rail vertical and snake, worm or zig-zag. If you see one

of these two types of fences in the park, they represent where a fence was during

the battle.

Observation Tower

Built by the War Department in 1896 as part of the early development efforts by the

military to create an open-air classroom at the battlefield. The tower is located at

a corner of "Bloody Lane" and is open except during inclement weather.

As the fighting in the cornfield was coming to a close, Maj. Gen. William H. French was moving his Federals forward to support Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick and veered into Confederate Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill's troops posted in the Sunken Road. Fierce fighting continued here for four hours before exhaustion overwhelmed both sides.

Bloody Lane

On the morning of September 17, 1862, three divisions of Gen. Edwin Sumner's Second

Corps crossed Antietam Creek. The first division moved toward the West Woods while

the other two divisions advanced to the Sunken Road. General William Henry French's

division led the attack. Within an hour, General Israel Richardson was in position to

support him. Outnumbered, the Confederates in the road stood their ground for nearly

three hours. Finally, the Federals were successful in driving them from this strong

position. In three hours of combat 5,500 soldiers were killed or wounded and neither

side gained a decisive advantage.

Quoted From: Bloody Lane Trail

Antietam

132 Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry

1 Brigade

2 Division

2 Corps

September 17, 1862

Casualties at Antietam

Killed 30

Wounded 114

Missing 8

Total 152

Battles Participated In: Antietam, Md. Sept. 17, 1862 Fredericksburg, Va. Dec. 13, 1862

Chancellorsville, Va. Apr. 30 -May 3, 1863

Recruited In: Montour, Wyoming, Bradford, Columbia, Carbon and Luzerne Counties.

Virtue, Liberty and Independence

Erected by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania

Quoted From: Antietam National Battlefield - 132nd Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Monument (U.S. National Park Service)

130th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Monument

2 Brigade

3 Division

2 Corps

This memorial marks the Regiment's right of line in Battle, its left extended to Roulette's

Lane below; it went into battle by way of the Roulette farm buildings, about 9:30 A.M.,

and driving back the enemy, maintained its position at and immediately Northeast of this

point on the high ground overlooking Bloody Lane until 1:30 o'clock P.M. when withdrawn

to replenish its exhausted ammunition, and then occupied the reserve line.

Casualties at Antietam

Killed in battle 32

Died from wounds 14

Non-fatal wounds 132

Total 178

Recruited in Cumberland, York, Montgomery, Dauphin and Chester Counties.

Virtue, Liberty and Independence

Erected by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania

Quoted From: Antietam National Battlefield - 130th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Monument (U.S. National Park Service)

On the southeast side of town, Union Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside's troops had been trying to cross Antietam Creek since mid-morning. Around 1 p.m., they finally cross the bridge and took the heights. After a 2 hour lull to reform the Union lines, they advanced up the hill, driving the Confederates back towards Sharpsburg. But for the timely arrival of Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill's division from Harpers Ferry, Burnside would have entered Sharpsburg. Instead, the Union troops were driven back to the heights above the bridge.

The Final Attack Trail

After capturing the Burnside Bridge, approximately 8,000 Union soldiers reorganized on

this side of Antietam Creek. Forming a line of battle a wide mile, they advanced across

the ground that you will walk for the final attack to drive Robert E. Lee's Confederate

army from Maryland. In this part of the battle, which lasts from 3:00 p.m. to 5:30 p.m.,

there were five times as many casualties than there were in the action at the Burnside

Bridge. Two Generals were killed and Colonel Harrison Fairchild's Brigade of Union

soldiers suffered the highest percentage of casualties for any brigade in the Union army

at the Battle of Antietam. These final two and one-half hours of combat conclude the

twelve hour struggle that still ranks as the bloodiest one-day battle in American history.

Quoted From: The Final Attack Trail

William McKinley Monument

Sergeant McKinley Co. E. 23rd Ohio Vol. Infantry, while in charge of the Commissary

Department, on the afternoon of the day of the battle of Antietam, September 17, 1862,

personally and without orders served "hot coffee" and "warm food" to every man in

the Regiment, on this spot and in doing so had to pass under fire.

Quoted From: Antietam National Battlefield - Monument to William McKinley (U.S. National Park Service)

The battle was over with the Union sitting on three sides, waiting for the next day. During the night, General Lee pulled his troops back across the Potomac River, leaving the battle and the town to General McClellan.

The question historians have been debating for years is why McClellan did not pursue Lee and destroy the Army of Northern Virginia probably bringing the war to an end. That did not happen and it simply became another missed opportunity because of McClellan's hesitancy and indecisiveness.

Sources:

Antietam National Battlefield (U.S. National Park Service)

Antietam National Battlefield - Wikipedia

The Last Stop on the O'Leary's 2010 Tour was Back to the District

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.