English Victorian Neoclassical Painter

1861 - 1922

English Victorian Neoclassical Painter

1861 - 1922

His already estranged family, who had disapproved of him becoming an artist, was ashamed of his suicide and burned his papers. No photographs of Godward are known to survive.

Godward was born in 1861 and lived in Wilton Grove, Wimbledon.

He exhibited at the Royal Academy from 1887. When he moved to Italy with one of his models in 1912, his family broke off all contact with him and even cut his image from family pictures. Godward returned to England in 1919, died in 1922 and is buried in Brompton Cemetery, west London.

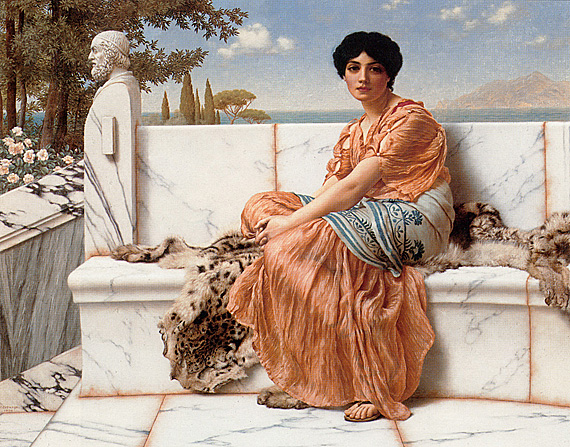

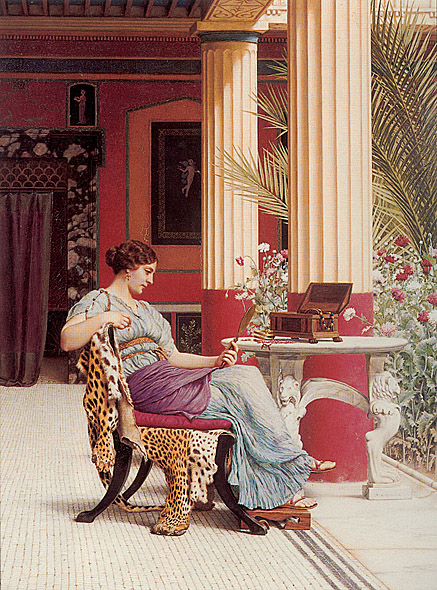

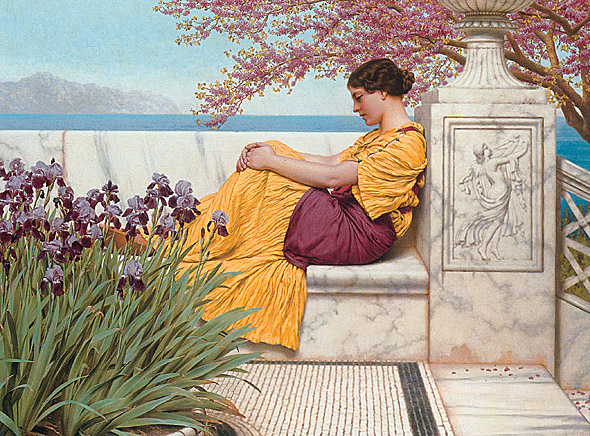

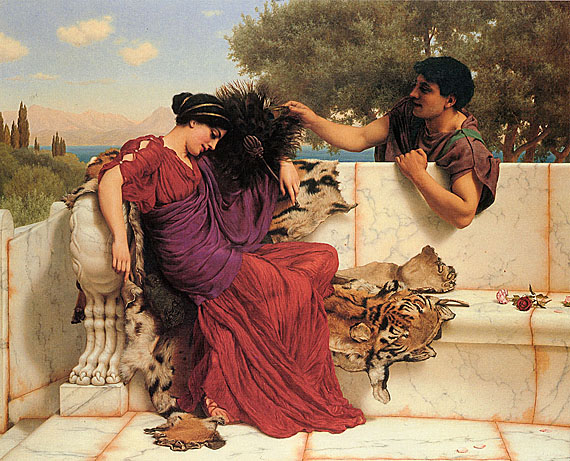

One of his best known paintings is Dolce far Niente (1904), which currently resides in the collection of Andrew Lloyd Webber. As in the case of several other paintings, Godward painted more than one version, in this case an earlier (and less well known) 1897 version.

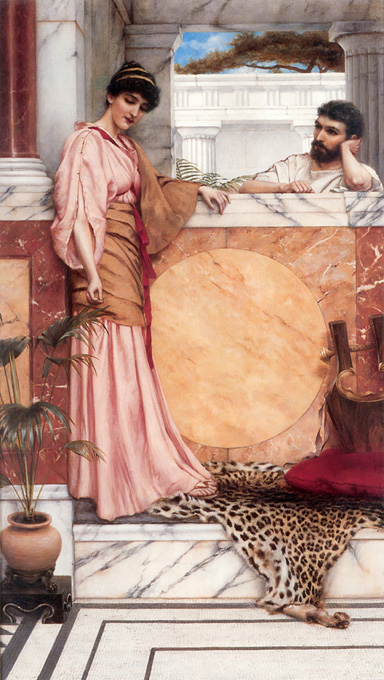

Godward was a Victorian Neo-classicist, and therefore a follower in theory of Frederic Leighton. However, he is more closely allied stylistically to Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, with whom he shared a penchant for the rendering of Classical architecture, in particular, static landscape features constructed from marble.

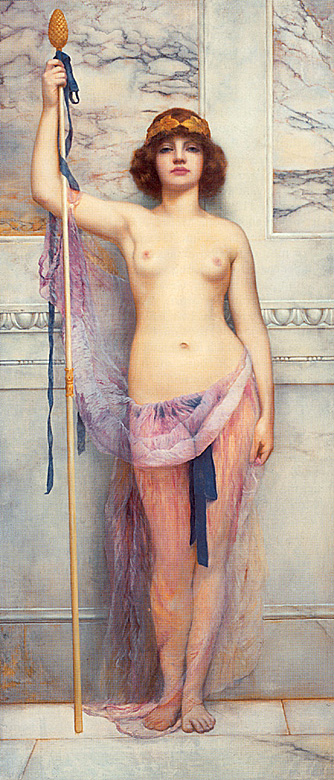

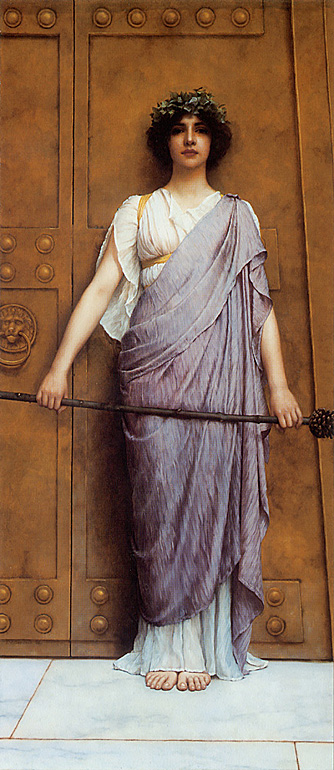

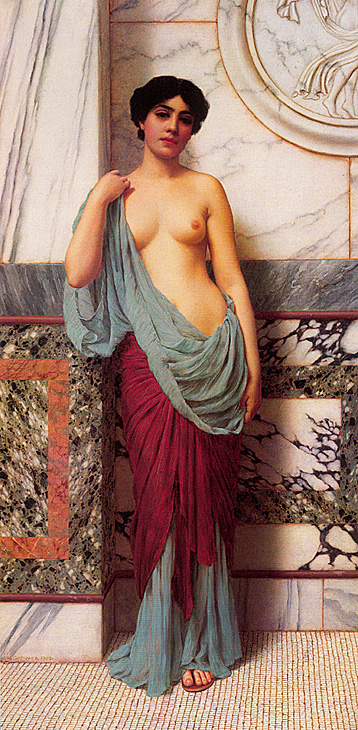

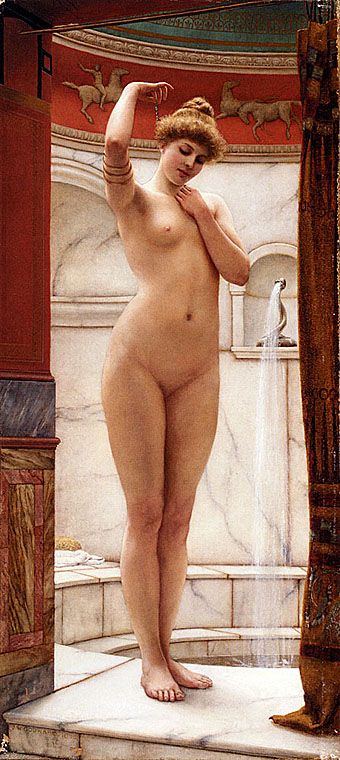

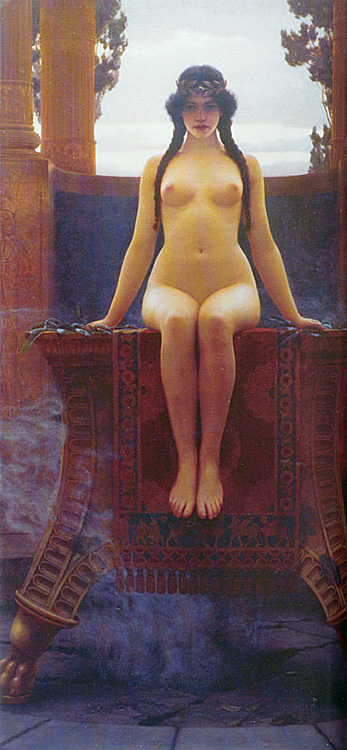

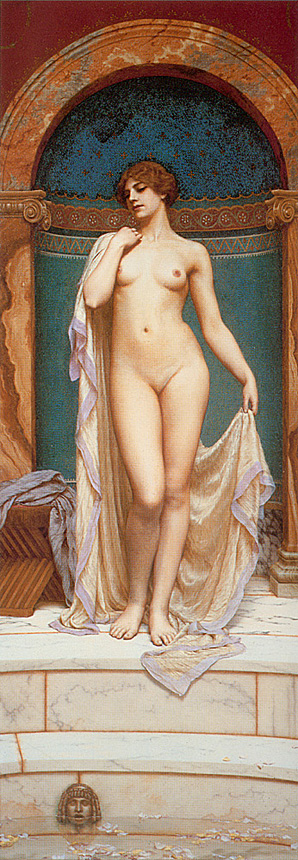

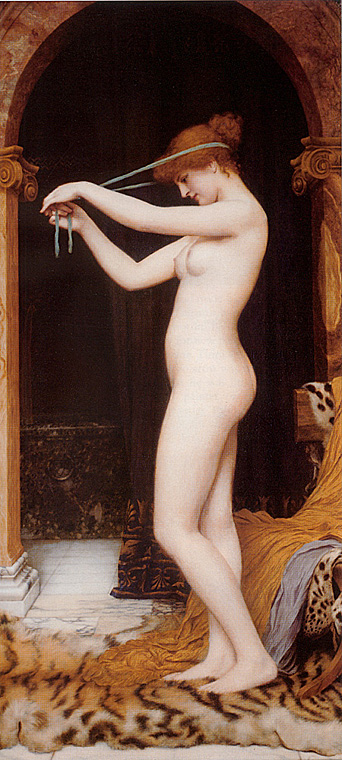

The vast majority of Godward's extant images feature women in Classical dress, posed against these landscape features, though there are some semi-nude and fully nude figures included in his oeuvre (a notable example being In The Tepidarium (1913), a title shared with a controversial Alma-Tadema painting of the same subject that resides in the Lady Lever Art Gallery). The titles reflect Godward's source of inspiration: Classical Civilization, most notably that of Ancient Rome (again a subject binding Godward closely to Alma-Tadema artistically), though Ancient Greece sometimes features, thus providing artistic ties, albeit of a more limited extent, with Leighton.

Given that Classical scholarship was more widespread among the potential audience for his paintings during his lifetime than in the present day, meticulous research of detail was important in order to attain a standing as an artist in this genre. Alma-Tadema was, as well as a painter, an archaeologist who attended historical sites and collected artifacts that were later used in his paintings: Godward, too, studied such details as architecture and dress, in order to ensure that his works bore the stamp of authenticity. In addition, Godward painstakingly and meticulously rendered those other important features in his paintings, animal skins (the paintings Noon Day Rest (1910) and A Cool Retreat (1910) contain superb examples of such rendition) and wild flowers (Nerissa (1906), illustrated above, and Summer Flowers (1903) are again excellent examples of this).

The appearance of beautiful women in studied poses in so many of Godward's canvases causes many newcomers to his works to categorize him mistakenly as being Pre-Raphaelite, particularly as his palette is often a vibrantly colorful one. However, the choice of subject matter (ancient civilization versus, for example, Arthurian legend) is more properly that of the Victorian Neoclassicist: however, it is appropriate to comment that in common with numerous painters contemporary with him, Godward was a 'High Victorian Dreamer', producing beautiful images of a world which, it must be said, was idealized and romanticized, and which in the case of both Godward and Alma-Tadema came to be criticized as a world-view of 'Victorians in togas'.

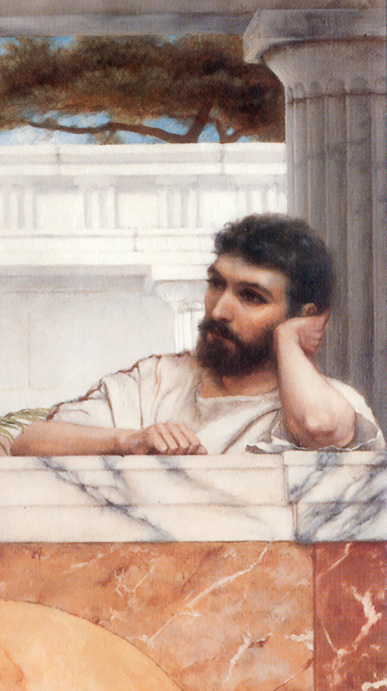

The serene beauty and astonishing technical execution of John William Godward's paintings contradict the fact that this important artist has received virtually no critical acclaim or art historical recognition. We know little about this artist's private life, which is not betrayed by his art. Melancholy, kindly, reclusive, handsome, talented and shy, J. W. Godward's life is still a mystery, a censored book, protected by himself and sealed by his family. Unlike most Olympian Classicists before him, he preferred anonymity and privacy.

Ignored by the quickly changing tastes of the art critics, Godward became the climatic figure of English classical-subject painting as this genre itself shriveled under the blaze of the 20th century avant-garde. He was the best of the last great European painters to straight-forwardly embrace classical Greece and Rome in their art. Herein lies his significance to art history. With him and his colleagues, we see the nightfall of five hundred years of Classical subject painting in Western art.

Desperately idealistic, Godward was one of those artists, who at first glance, we think we fathom completely. Since he is often dismissed with the inadequate catch phrases: an Alma-Tadema clone, a "too late" Classicist, a "pedant of the brush", a "pot-boiler" or merely the painter of an insipid world of languorous women on marble benches, no serious study of his art has been undertaken. And because we are a society that honors "firsts" rather than "lasts" few art historians have examined the demise of Classical subject-painting, of which Godward is a chief exemplar. All of these judgments, in the light of historical distance, can be seen as unjust prejudices.

In Godward's work we see the final summation of half a millennium of Classical antique influence on Western painting. Next to Christianity it was by far the greatest outside influence on European painting. It vanished during Godward's generation -- killed, as it were, by contemporary nihilistic philosophies. While pointed references to Classicism continued, even unto today, the idealistic rhetoric accompanying it has died. During a period of rapidly declining interest in Greco-Roman antiquity courageous artists from the 19th century continued, against all odds, in this field for the first third of the 20th century.

Godward was one of the greatest practitioners of the Classical ideal. His art represents the summation of this incredibly important paradigm. What Godward does represent, is a microcosm for all Classicists during a period aptly called "The Twilight of the Gods" or "The Eclipse of Classicism." In the bigger picture his career offers the clearest example of the death of the classical Greco-Roman subject painting. A slightly younger generation after Godward also saw the demise of modern-style classicism in the hostile environment of the early 20th century.

Christopher Wood, who is greatly responsible for the resurrection of many obscure artists, like Godward, described him in the first edition of his Dictionary of Victorian Painters as an "imitator of Lawrence Alma-Tadema with whom he is sometimes confused." In the second edition this was amended to: "He developed his own very personal variation on the Alma-Tadema theme." This simple correction clearly demonstrates the increased attention being focused on Godward's pictures as his prices rose. For, in reality, very few of us could ever confuse a Godward with an Alma-Tadema.

This neglect has continued unto today, when private collectors have begun to include him in their collections at prices rivaling those of Tadema himself. Art historians are now beginning to evaluate both Godward and his post-Olympian contemporaries, the "Last Classicists." The reason for this upsurge in appreciation is the realization that the quality of his work compares favorably with other late 19th and early 20th century Classicists. Over a remarkably consistent career of almost forty years he created a vital niche for his art.

This reclusive genius has now become too important not to have a monograph written about him. Except for Godward's death notice, nothing more than a paragraph has been written about him. His pictures have 'bullied' their own way to the top of the Victorian price scale on their own merits, not with the help of scholarly promotion. Since Godward never spoke for himself, except while exploring a private world of his own through his art. This publication must speak on his behalf. It will allow us to critically come to grips with this most enigmatic artist we all think we know, but in reality do not know at all.

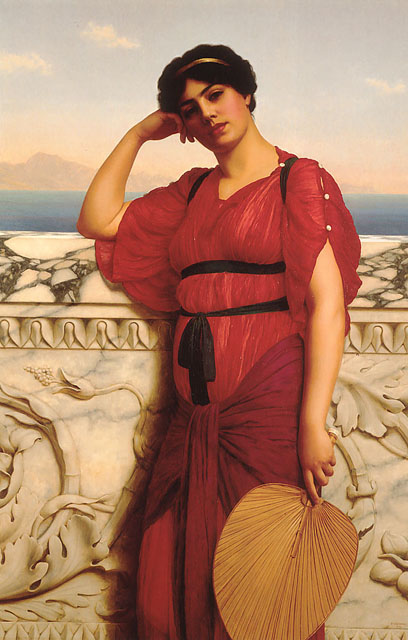

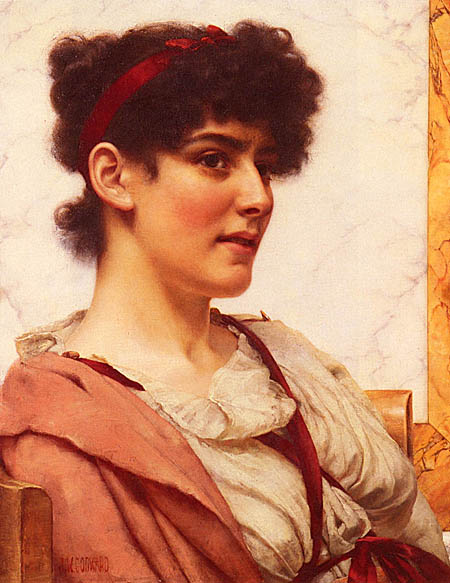

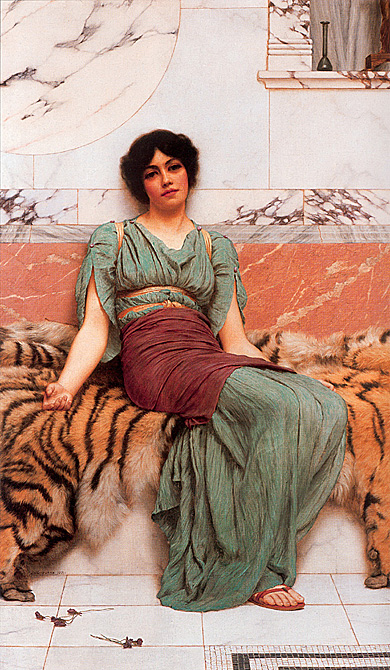

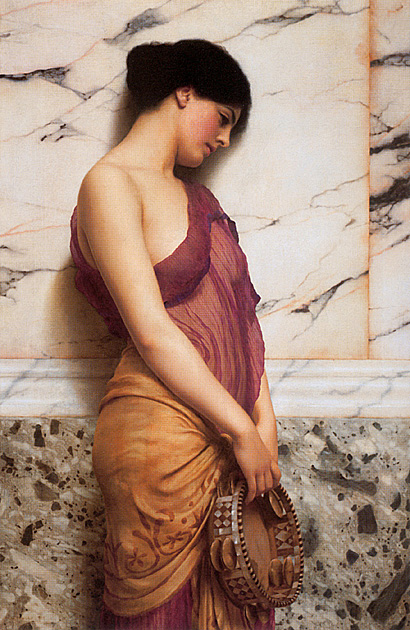

A Classical Beauty is a fine and subtle example of Godward's early work in which the technical quality of his paint is at its best. This was the result of a slow build up of very thin translucent glazes creating a luminosity of colour. Godward's reputation for his ability to create realistic rendering of marble rivalled and outstripped that of his mentor, Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema. His interest in Classical antiquity is reflected not only in the settings that he uses for his paintings but also in the details of the drapery. This revival of interest in classical history in the second half of the nineteenth century by artists such as Godward, Leighton, Poynter and Alma-Tadema proved extremely popular amongst prominent members of society as it mirrored their affluence and sense of justice.

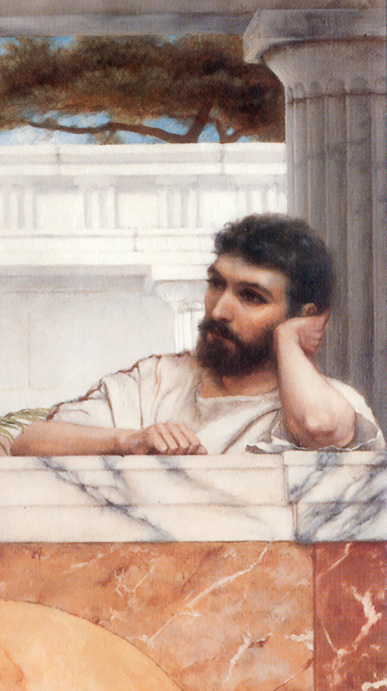

MELIBOEUS / TITYRUS

MELIBOEUS

You, Tityrus, 'neath a broad beech-canopy

Reclining, on the slender oat rehearse

Your silvan ditties: I from my sweet fields,

And home's familiar bounds, even now depart.

Exiled from home am I; while, Tityrus, you

Sit careless in the shade, and, at your call,

"Fair Amaryllis" bid the woods resound.

TITYRUS

O Meliboeus, 'twas a god vouchsafed

This ease to us, for him a god will I

Deem ever, and from my folds a tender lamb

Oft with its life-blood shall his altar stain.

His gift it is that, as your eyes may see,

My kine may roam at large, and I myself

Play on my shepherd's pipe what songs I will.

MELIBOEUS

I grudge you not the boon, but marvel more,

Such wide confusion fills the country-side.

See, sick at heart I drive my she-goats on,

And this one, O my Tityrus, scarce can lead:

For 'mid the hazel-thicket here but now

She dropped her new-yeaned twins on the bare flint,

Hope of the flock- an ill, I mind me well,

Which many a time, but for my blinded sense,

The thunder-stricken oak foretold, oft too

From hollow trunk the raven's ominous cry.

But who this god of yours? Come, Tityrus, tell

TITYRUS

The city, Meliboeus, they call Rome,

I, simpleton, deemed like this town of ours,

Whereto we shepherds oft are wont to drive

The younglings of the flock: so too I knew

Whelps to resemble dogs, and kids their dams,

Comparing small with great; but this as far

Above all other cities rears her head

As cypress above pliant osier towers.

MELIBOEUS

And what so potent cause took you to Rome?

TITYRUS

Freedom, which, though belated, cast at length

Her eyes upon the sluggard, when my beard

'Gan whiter fall beneath the barber's blade

Cast eyes, I say, and, though long tarrying, came,

Now when, from Galatea's yoke released,

I serve but Amaryllis: for I will own,

While Galatea reigned over me, I had

No hope of freedom, and no thought to save.

Though many a victim from my folds went forth,

Or rich cheese pressed for the unthankful town,

Never with laden hands returned I home.

MELIBOEUS

I used to wonder, Amaryllis, why

You cried to heaven so sadly, and for whom

You left the apples hanging on the trees;

'Twas Tityrus was away. Why, Tityrus,

The very pines, the very water-springs,

The very vineyards, cried aloud for you.

TITYRUS

What could I do? how else from bonds be freed,

Or otherwhere find gods so nigh to aid?

There, Meliboeus, I saw that youth to whom

Yearly for twice six days my altars smoke.

There instant answer gave he to my suit,

"Feed, as before, your kine, boys, rear your bulls."

MELIBOEUS

So in old age, you happy man, your fields

Will still be yours, and ample for your need!

Though, with bare stones o'erspread, the pastures all

Be choked with rushy mire, your ewes with young

By no strange fodder will be tried, nor hurt

Through taint contagious of a neighbouring flock.

Happy old man, who 'mid familiar streams

And hallowed springs, will court the cooling shade!

Here, as of old, your neighbour's bordering hedge,

That feasts with willow-flower the Hybla bees,

Shall oft with gentle murmur lull to sleep,

While the leaf-dresser beneath some tall rock

Uplifts his song, nor cease their cooings hoarse

The wood-pigeons that are your heart's delight,

Nor doves their moaning in the elm-tree top.

TITYRUS

Sooner shall light stags, therefore, feed in air,

The seas their fish leave naked on the strand,

Germans and Parthians shift their natural bounds,

And these the Arar, those the Tigris drink,

Than from my heart his face and memory fade.

MELIBOEUS

But we far hence, to burning Libya some,

Some to the Scythian steppes, or thy swift flood,

Cretan Oaxes, now must wend our way,

Or Britain, from the whole world sundered far.

Ah! shall I ever in aftertime behold

My native bounds- see many a harvest hence

With ravished eyes the lowly turf-roofed cot

Where I was king? These fallows, trimmed so fair,

Some brutal soldier will possess these fields

An alien master. Ah! to what a pass

Has civil discord brought our hapless folk!

For such as these, then, were our furrows sown!

Now, Meliboeus, graft your pears, now set

Your vines in order! Go, once happy flock,

My she-goats, go. Never again shall I,

Stretched in green cave, behold you from afar

Hang from the bushy rock; my songs are sung;

Never again will you, with me to tend,

On clover-flower, or bitter willows, browse.

TITYRUS

Yet here, this night, you might repose with me,

On green leaves pillowed: apples ripe have I,

Soft chestnuts, and of curdled milk enow.

And, see, the farm-roof chimneys smoke afar,

And from the hills the shadows lengthening fall!

"The goddess replied to my questions, as she talks, her lips breathe spring roses: 'I was Chloris, whom am now called Flora. Latin speech corrupted a Greek letter of my name. I was Chloris, Nympha of the happy fields (Elysion), the homes of the blessed (you hear) in earlier times. To describe my beauty would mar my modesty: it found my mother a son-in law god. It was spring, I wandered; Zephyrus (the West Wind) saw me, I left. He pursues, I run: he was the stronger; and Boreas gave his brother full rights of rape by robbing Erechtheus' house of its prize (Oreithyia). But he makes good the rape by naming me his bride, and I have no complaints about my marriage. I enjoy perpetual spring: the year always shines, trees are leafing, the soil always fodders. I have a fruitful garden in my dowered fields, fanned by breezes, fed by limpid fountains. My husband filled it with well-bred flowers, saying: 'Have jurisdiction of the flower, goddess.' I often wanted to number the colors displayed, but could not: their abundance defied measure. As soon as the dewy frost is cast from the leaves and sunbeams warm the dappled blossom, the Horae (Seasons) assemble, hitch up their colored dresses and collect these gifts of mine in light tubs. Suddenly the Charites (Graces) burst in, and weave chaplets and crowns to entwine the hair of gods. I first scattered new seed across countless nations; earth was formerly a single color. I first made a flower from Therapnean blood [Hyakinthos the hyacinth], and its petal still inscribes the lament. You, too, narcissus, have a name in tended gardens, unhappy in your undivided self. Why mention Crocus, Attis or Cinyras' son, from whose wounds I made a tribute soar?" - Ovid, Fasti 5.193

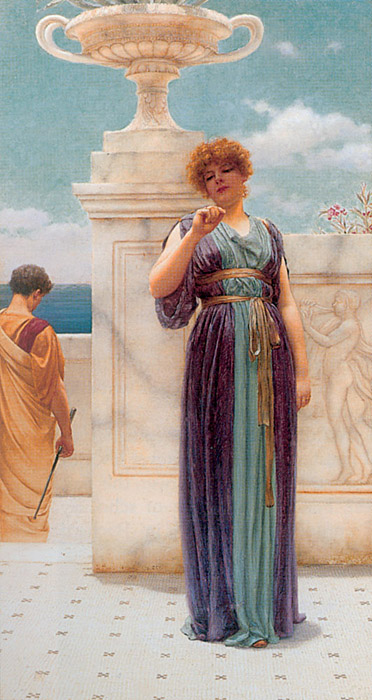

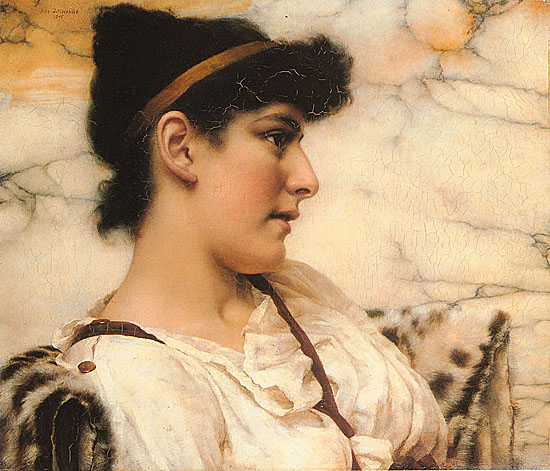

Interestingly, the woman featured in this work is viewed from below, giving her an almost monumental appearance. Her head is framed by an impressive marble wall and gilt pilaster. She was Godward's favorite model; an Italian woman who some scholars suggest may have been the object of the artist's affection.

The academic treatment and highly polished finish of this painting brings to mind the works of Frederic Leighton and Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, whose work Godward admired. The composition also displays many of the hallmarks of the wider aesthetic movement prevalent at the end of the century, which promoted the importance of formal and sensual qualities over visual narrative.

Swanson noticed, however, that other private collectors and dealers were taking an interest, and that the J Paul Getty Museum in Malibu had three Godward oils, though they were seldom put on display, being "considered kitsch by their curators". Nevertheless, he predicted, "This present condition will probably change with the new millennium, bringing with it a new pattern of thinking and appreciation."

That's Aquarian reasoning, but Swanson is a keen defender, even as he gives generous ground to cynics.

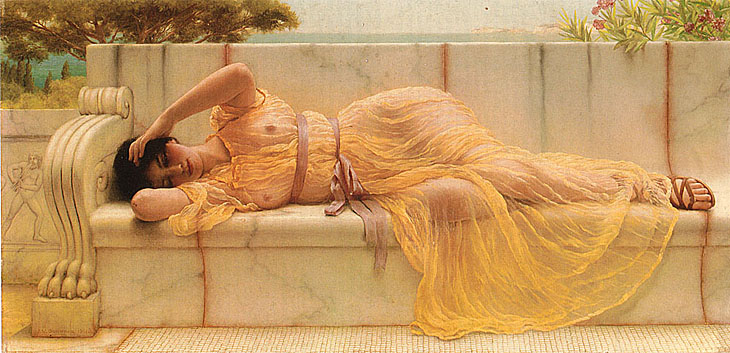

Thomas McLean, London (purchased from the artist on July 15, 1901 and listed as Girl in yellow Drapery). A letter from Thomas McLean with a sketch to the artist (July 15, 1901) notes that Dr Vern Swanson writes, "A sultry Roman maiden, wearing see through yellow drapery, reclines upon a long marble bench. She shields her eyes from the bright sun, hoping to see her lover for a mid-day rendezvous. The painting is one of Godward's most sensuous female figures, the streaming gown covering everything but the girl's modesty.

Muse, sing the deeds of golden Aphrodite,

Who wakens with her smile the lulled delight

Of sweet desire, taming the eternal kings

Of Heaven, and men, and all the living things

That fleet along the air, or whom the sea,

Or earth, with her maternal ministry,

Nourish innumerable, thy delight

All seek ... O crowned Aphrodite!

Three spirits canst thou not deceive or quell:

Minerva, child of Jove, who loves too well

Fierce war and mingling combat, and the fame

Of glorious deeds, to heed thy gentle flame.

Diana ... golden-shafted queen,

Is tamed not by thy smiles; the shadows green

Of the wild woods, the bow, the...

And piercing cries amid the swift pursuit

Of beasts among waste mountains,-such delight

Is hers, and men who know and do the right.

Nor Saturn's first-born daughter, Vesta chaste,

Whom Neptune and Apollo wooed the last,

Such was the will of aegis-bearing Jove;

But sternly she refused the ills of Love,

And by her mighty Father's head she swore

An oath not unperformed, that evermore

A virgin she would live mid deities

Divine: her father, for such gentle ties

Renounced, gave glorious gifts-thus in his hall

She sits and feeds luxuriously. O'er all

In every fane, her honours first arise

From men-the eldest of Divinities.

These spirits she persuades not, nor deceives,

But none beside escape, so well she weaves

Her unseen toils; nor mortal men, nor gods

Who live secure in their unseen abodes.

She won the soul of him whose fierce delight

Is thunder-first in glory and in might.

And, as she willed, his mighty mind deceiving,

With mortal limbs his deathless limbs inweaving,

Concealed him from his spouse and sister fair,

Whom to wise Saturn ancient Rhea bare.

but in return,

In Venus Jove did soft desire awaken,

That by her own enchantments overtaken,

She might, no more from human union free,

Burn for a nursling of mortality.

For once amid the assembled Deities,

The laughter-loving Venus from her eyes

Shot forth the light of a soft starlight smile,

And boasting said, that she, secure the while,

Could bring at Will to the assembled Gods

The mortal tenants of earth's dark abodes,

And mortal offspring from a deathless stem

She could produce in scorn and spite of them.

Therefore he poured desire into her breast

Of young Anchises,

Feeding his herds among the mossy fountains

Of the wide Ida's many-folded mountains,

Whom Venus saw, and loved, and the love clung

Like wasting fire her senses wild among

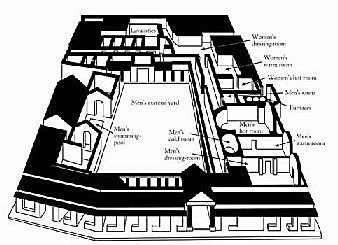

Communal bathing in public facilities was, therefore, an important and essential part of Roman life, and formed part of the daily routine for all classes in Rome. Cicero writes "the gong that announced the opening of the public baths each day was a sweeter sound, than the voices of the philosophers in their school". The thermae were all-encompassing establishments acting as social, recreational, and cultural centres. Much of daily Roman life surrounded the thermae and a good proportion of a citizen's day would be spent there.

The general scheme consisted of a large open garden surrounded by subsidiary rooms and a block of bath chambers either in the centre of the garden, as in the Baths of Caracalla, or at its rear, as in the Baths of Titus. The main block contained three large bath chambers--the frigidarium, calidarium (caldarium), and tepidarium--smaller bathrooms, and courts. In addition to bathing facilities they would include sports centers, swimming pools, parks, libraries, lecture halls, small theatres, large halls for parties, restaurants and sleeping quarters.

Roman engineers devised an ingenious system of heating the baths-the hypocaust by which the floor was raised off the ground by pillars and spaces were left inside the walls so that hot air from the furnace could circulate through these open areas. Rooms requiring the most heat were placed closest to the furnace, whose heat could be increased by adding more wood. Large numbers of people were, therefore, offered an enclosed place that was always warm. At a time when, no matter how cold it became, people had no source of heat at home other than braziers and wore overcoats in the house as well as in the street; the baths were a place to keep warm.

Providing social and recreational activities was a basic responsibility for Roman rulers and the larger baths were owned by the state. They were frequently the pet projects of the Roman emperors, and, to ensure their popularity, and the emperor's notoriety, entrance fees were kept to the very minimum.

The Roman workday began at sunrise, with work being complete around noon, which was the time when the baths were generally visited. Republican bathhouses often had separate bathing facilities for women and men, but by the empire the custom was to open the bathhouses to women during the early part of the day and reserve it for men from 2:00 pm until closing time (usually sundown). As a rule, men and women bathed separately. Mixed bathing is first recorded in the 1st century AD, and was condemned by respectable citizens and prohibited by the emperors Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius. Women who were concerned about their respectability did not frequent the baths when the men were there, and the baths were an excellent place for prostitutes to ply their trade.

The Roman bathing ritual had a standardized pattern and generally regular routine, which the thermae were designed to accommodate. The exception was when bathers were taking the baths as part of a medical treatment; their physician would then prescribe which rooms to visit. The bathers first entered the apodyterium (dressing room) to change from their outdoor clothes, then proceeded to the elaeothesium or unctuarium to be anointed with oil. It was then normal to have a strenuous workout in the large courtyard area (palaestra) at the centre of the thermae, where various sports and activities were available. Exercises would include weight lifting, running, and ball games. After this the visitor proceeded to the series of main bathing rooms that varied dramatically in temperature. The calidarium (hot room), the sudatorium, or laconicum (steam room), where bathers had their bodies scraped of its accumulation of oil and perspiration with a curved metal implement called a strigil, the tepidarium (warm room), the largest and most luxurious in the thermae, and the frigidarium (cold room), where there was frequently a swimming pool. The bathing process was completed after the body was again anointed with oil.

After their baths, patrons could stroll in the promenades and gardens, visit the library or museum, watch performances of jugglers or acrobats, listen to a readings by poets, philosophers and politicians, or buy a snack from the many food vendors. They would meet friends and conduct business. Life at the baths was like life at the beach in summertime; the greatest pleasures were to mix with the crowd, to meet people, to listen to conversations, to tell stories, and to show off.

The buildings were among the most splendid and expensive of the imperial works, and made the splendor of a royal residence accessible to all. Lounges with covered colonnades for relaxation and socializing were provided. Writers frequently comment on the beauty and luxury of the bathhouses, with their, rich furnishings, high vaulted ceilings, brightly coloured mosaics, paintings, marble panels, and silver faucets and fittings. Christians and philosophers denied themselves the array of pleasures available at the thermae, or the "Cathedrals of Flesh," as they were known by Christians.

Blackburn mentions Godward's "Other" oil in Summer Exhibition at Burlington House in 1896 -- Campaspe. While more anemic in everything but size it depicted the beautiful concubine of Alexander the great. Apelles fell in love with her while she modeled for his Venus Anadyomene. According to Pliny, Alexander gave her up to Apelles. The painting attracted in its day much praise from London critics, A. G. Temple for one:

J. W. Godward, too in his straightforward and clear delineation of form so wholesomely academic in its workmanship has instanced his uncommon capacity in many examples, of which few are finer than the Campaspe of 1896.

Yet in the hands of Oman Jean writer for The Studio the same canvas elicits more vituperative comments:

Mr. John Godward brings us back to the school of mere imitation -- futile, un-mysterious and inharmonious in art, as mere imitation is to music. Behind a nude figure is a mosaic, so marvelously reproduced that it seems a pity the form obscures it. The piece of marble which, as it were, forms the plinth of this living statue, is so real that one pities the poor creature with frozen feet. But all this is comparatively simple. The difficult task was the naked figure (Campaspe), and despite the artist's most admirable intentions, one cannot fair to remark that the right hand is defective, as is the drawing of the shoulders. And yet it is in things like these that true beauty resides, and the true difficulty into the bargain; not in vain imitations of un-picturesque objects.

Drusilla was born in Abitarvium, north of the later city of Koblenz, Germany. She was married in 33 to Lucius Cassius Longinus. The couple divorced in 37. By that time Caligula had reputedly become a lover to all three of his sisters, and he may have instructed the couple to divorce. Shortly after however, Drusilla had her second marriage, to Marcus Aemilius Lepidus. He was reputed to have been one of Caligula's lovers by later historians.

Drusilla was reportedly her brother's favorite. There are also rumors that she was also his lover. If true, that role likely gained her influence over Caligula. Though the activities between the brother and sister might have been seen as incest by their contemporaries, it is not known whether the two actually had any sexual relations. Drusilla herself earned a rather poor reputation because of the close bond she shared with Caligula and was even likened to a prostitute by later scholars, in an attempt to discredit Caligula's private life.

She died on June 10, 38, probably of fever which was rampant in Rome at the time.

Caligula never really recovered from the loss. He buried his sister with the honors of an Augusta, acted as a grieving widower, and had the Roman Senate declare her a Goddess as "Diva Drusilla", deifying her as a representation of the goddess Venus or Aphrodite. Drusilla was consecrated as Panthea, most likely on the anniversary of the birthday of Augustus.

A year later, Caligula named his only known daughter Julia Drusilla after his late favorite sister. Meanwhile, her widowed husband Marcus Aemilius Lepidus reportedly became a lover to her sisters Livilla and Agrippina in an apparent attempt to gain their support in succeeding Caligula. The conspiracy was discovered by Caligula while in Germania Superior during the autumn. Lepidus was swiftly executed.

Some suggest that Caligula was motivated by more than mere lust or love in pursuing relations with his sisters. He might instead have deliberately patterned himself after the Hellenistic Monarchs of the Ptolemaic dynasty where marriages between jointly ruling brothers and sisters had become tradition rather than sex scandals. This has also been used to explain why his despotism was apparently more evident to his contemporaries than those of his predecessors Caesar Augustus and Tiberius.

The source of many of the rumors surrounding Caligula and Drusilla may be derived from formal Roman dining habits. It was customary in Patrician households for the host and hostess of a dinner (or in other words, the husband and wife in charge of the household) to hold the positions of honor at a banquet at their residence. In the case of a young bachelor being the head of the household, the female position of honor was to be held by his sisters, taking turns sitting in the place of honor. Caligula apparently broke with this tradition in that rather than having his sisters take turns at the place of honor, the place was reserved exclusively for Drusilla. Caligula was thus, in a manner of speaking, publicly proclaiming that Drusilla was his wife, the female head of the household. It is possible that rumors of Caligula's incest with his sister stem from this action, and what may seem to us today to be a very minor action had devastating consequences within the context of ancient Roman society.

There a several subtle variations about the life of Endymion. Some sources suggest that he was a king of Elis, while other ancient authorities claim that he was a Carian. However, these different versions of Endymion's ancestry are much less important than the part of the myth that matters most, which is, of course, his relationship with the goddess Selene.

According to the myth, Selene, the eternally beautiful goddess of the Moon, gazed upon Endymion and fell madly in love with him. It is said that in time Selene bore the handsome mortal fifty daughters. Scholars have suggested that the number of daughters is symbolic, with each daughter possibly representing an individual month of an Olympiad.

Certainly, the story of a mortal and an immortal engaging in a legendary affair is interesting enough, but there is even more to this intriguing tale. It is important to remember that, as a mortal, Endymion was subject to the fate that we all share - aging and eventual death. However, the Greek gods and goddesses did not age and die. Instead, the gods of Greece remained young and beautiful for all time. The relationship between Endymion and Selene, therefore, faced some serious problems. Selene came up with a solution to this dilemma. According to one version of the myth, the goddess of the Moon cast a spell on her lover, making him sleep forever. In this state of eternal slumber, Endymion kept both his youth and his good looks.

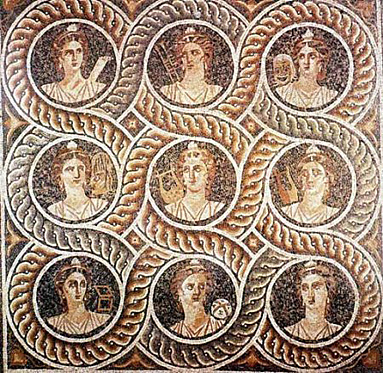

Hesiod, Theogony:

"The Mousai sang who dwell on Olympos, nine daughters begotten by great Zeus, Kleio and Euterpe, Thaleia, Melpomene and Terpsikhore, and Erato and Polyhymnia and Ourania and Kalliope."

Isyllus, Hymn to Asclepius:

"Father Zeus bestowed the hand of the Mousa Erato on Malos (eponymous lord of Malea) in holy matrimony (hosioisi gamois.) The pair had a daughter Kleophema, who married Phlegyas, a native of Epidauros; and Phlegyas had by her a daughter Aigle, otherwise known as Koronis, whom Phoibos of the golden bough saw in the house of her grandfather Malos, and falling in love he got by her a child, Asklepios."

Nota Bene: This hymn was engraved on a limestone tablet unearthed at the shrine of Asklepios at Epidauros. According to the inscription the poet consulted the Delphic Oracle for approval before publishing this genealogy of the god Asklepios.

Plato, Phaedrus:

"When they (the grasshoppers) die they go and inform the Mousai in heaven who honors them on earth. They win the love of Terpsikhore for the dancers by their report of them; of Erato for the lovers."

Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica:

The poet invokes Erato as he begins the tale of the love of Jason and Medea: "Come, Erato, come lovely Mousa, stand by me and take up the tale. How did Medea's passion help Iason to bring back the fleece to Iolkos." Orphic Hymn to the Muses:

"Daughters of Mnemosyne and Zeus . . . Kleio, and Erato who charms the sight, with thee, Euterpe, ministering delight: Thalia flourishing, Polymnia famed, Melpomene from skill in music named: Terpsikhore, Ourania heavenly bright."

Ovid, Fasti:

"I (the poet) have much to ask of Rhea: `Give me, goddess, someone to interview.' Cybele saw her erudite granddaughters (the Mousai) and made them help . . . So Erato--Cytherea's (Aphrodite's) month April fell to her, since she is named from tender love so she tells the tale."

Propertius, Elegies:

"The nine Maidens, each allotted her own realm, busy their tender hands on their separate gifts : . . . another Erato with both hands plaits wreaths of roses (i.e. the flower of love)."

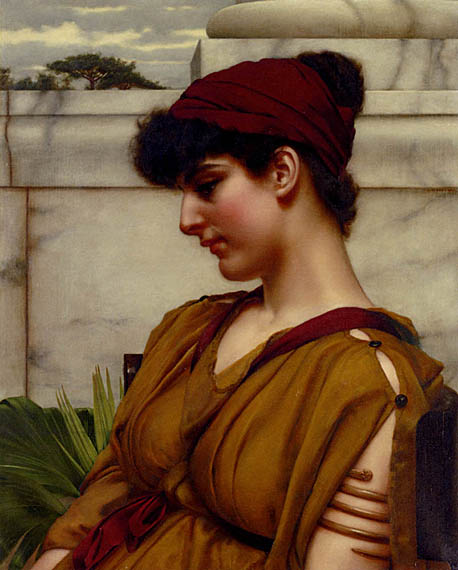

John William Godward devoted his entire career to the depiction of feminine beauty, painting favorite models again and again, in exquisite studies of beauty and color. His greatest talent was his skill at rendering textures and fabrics and his arrangement of beautiful forms to create an aesthetic ensemble. There is never any suggestion of threat or danger, or even any importance of narrative and in many ways Godward's work is similar to that of Albert Moore and James Abbot McNeil Whistler. Godward, Moore and Whistler shared an approach to art which, in the twentieth century became increasingly prevalent. Their work was essentially without narrative or dramatic charge, decorative and consciously devoid of any suggestion of movement or emotion. The women are always content, alluring and absorbed but what or who they dream of is not explained or important.

Godward specialized in portraying women alone in settings suggesting antiquity, usually decorative, dark-haired beauties in diaphanous gowns created with ingenious contrasts of colors and flesh tones.

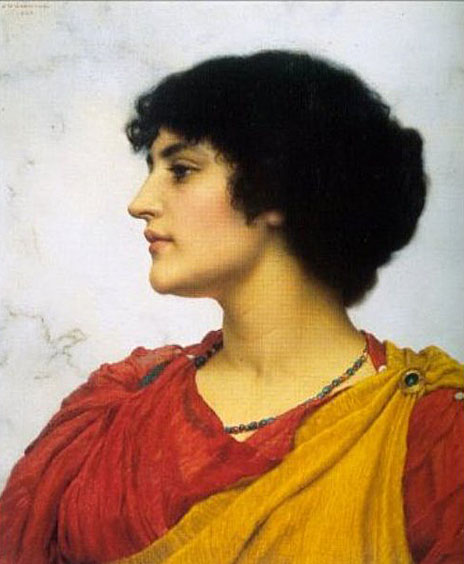

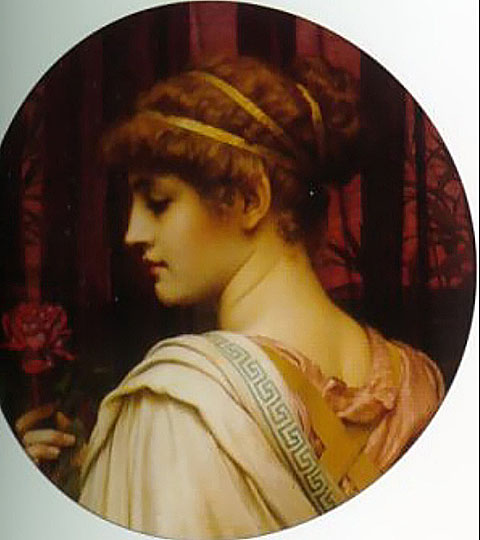

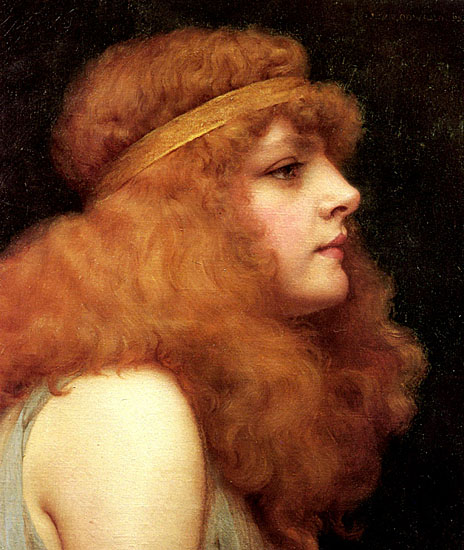

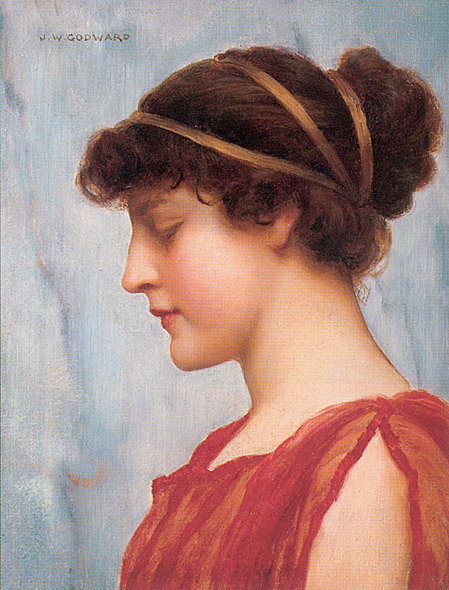

Godward was clearly drawn to the figure of Atalanta and painted another version of the huntress in 1899, looking towards the viewer and veiled for matrimony, (see Vern Swanson, John William Godward, The Eclipse of Classicism, p.198). This later and previously undocumented work, dated 1908, is a more successful composition, featuring a striking new model, Miss Goldsmith. Painted in profile, with bare shoulders and hair swept away from the neck, Godward's Atalanta is closely related to Leighton's painting of the same title painted in 1893. The golden band around Atalanta's arm is present in both works as well as the setting of the palace walls. As Atalanta is represented prepared for the race, her hair bound and her robes fastened loosely for running, Godward heightens the warmth and sensuality of her beautiful features by juxtaposing them with the coldness of marble.

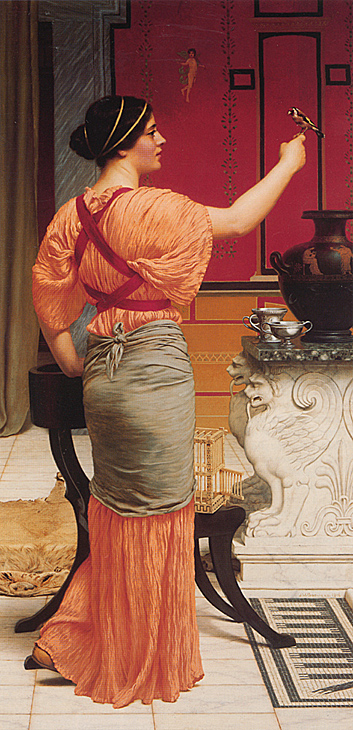

The suggestion of invitation created by the woman's act of drawing aside a curtain to her chamber is typical of the sensuality of Godward's work and bears a similarity to Tadema's The Frigidarium of 1890, in which a servant girl pulls back a curtain to reveal a bevy of naked bathers. The agate window in the present picture may also have been suggested to Godward by a painting by Tadema who painted the Mexican onyx windows of his own studio into Orante of 1907. The receding perspective of the tiny tesserae of the tiled floor of A Pompeian Lady is also reminiscent of Tadema, whose painting A Favourite Custom of 1909 (Tate) shares this element, as well as other details such as the doorway hung with dark-colored curtains and the table supported by a leg in the form of a lion. A Favourite Custom was one of Tadema's last contributions to the annual summer exhibitions at the Royal Academy and it was left to artists like Godward and his contemporaries to continue the fashion for pictures of the classical world.

The same claret hued curtain embroidered with gold thread had appeared in Winding the Skein of 1896 and Idle Thoughts of 1898 and a similar curtain appears in The New Perfume of 1914. The New Perfume also includes a carved table leg in the form of a panther which is similar to the lion-headed table-leg in A Pompeian Lady. This classical motif had also appeared in other works by Godward including Reflections of 1893 and The Toilette of 1900. These elements were carefully chosen by Godward to suggest an ancient classical world for his exotic beauties, rather than as an archaeological reconstruction of the past. There are various elements common to Godward's work; marble walls, exotic fabrics, voluptuous women and perhaps a piece of classical sculpture. The narrative of the pictures is usually minimal and there is rarely an emotional charge to the paintings, as has been remarked by Elizabeth Prettejohn; 'The sense of abstract design predominates; Godward's pictures rarely introduce even a hint of narrative content or psychological interest... The seamless modeling of the flesh and the figure's sultry but unfathomable glance introduce a sensuality that the rational composition keeps under rigorous control. The ancient setting and accessories are an essential component of the picture's mood of distanced sensuality... The tensions between antique remoteness and 'life like' rendering of textures, between cold marble and soft flesh, between abstract design and sensual appeal are essential to the picture's impact.' Godward's paintings depict an uncomplicated world of beauty in an age which is vaguely classical but has never really existed beyond the imagination of the artist and the poet.

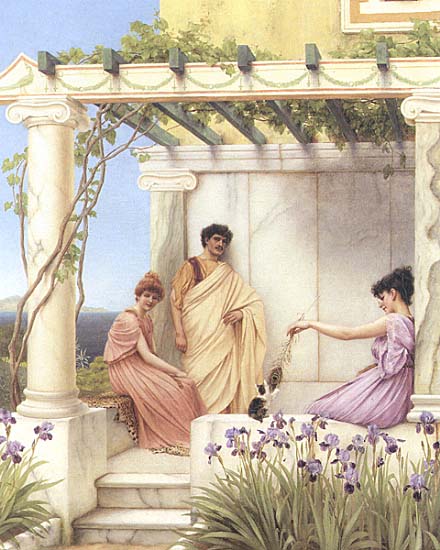

He Loves Me, He Loves Me Not is one of the most successful paintings by Godward from this period. It epitomizes the artist's obsession with the classical ideal, which inevitably led Godward to Rome in 1910, where he kept a studio in the Villa Strohl Fern. Throughout his career, Godward remained a faithful practitioner of classical Greco-Roman subject painting, seducing the viewer with depictions of beautiful, idealized women in reverie painted with an unsurpassed technical mastery.

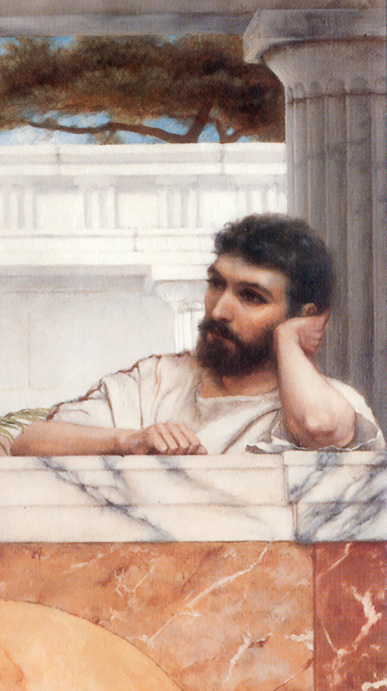

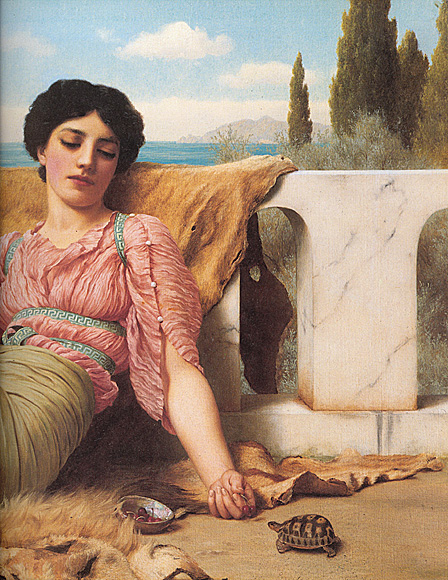

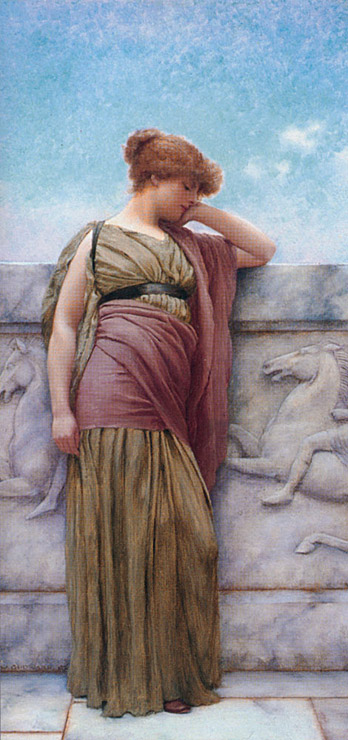

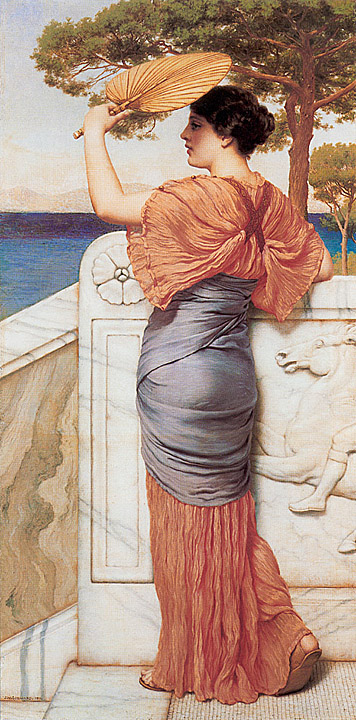

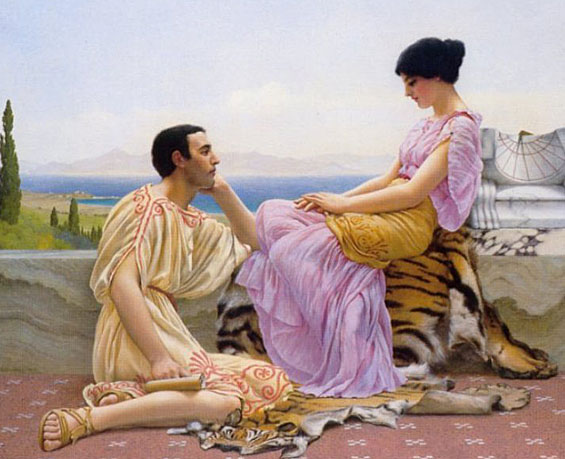

Leisure Hours is a fine example of a familiar theme in Godward's oeuvre. The McLean exhibition catalogue describes the painting as '...a Greek Girl seated by a balustrade looking out to sea.' A dark haired Greek woman wearing a golden tunic with a mauve stola looks out to the horizon of the sea. She awaits a lover or dreams of faraway fantasies. Her fan is carelessly tossed to the ground, as she sits upon a wooden Savonarola chair. The marble balustrade is sculpted with bas-reliefs of sword-fighting soldiers. Perhaps it hints at her own soldier-man returning from foreign conquests.

_BMJ.jpg)

"Long misunderstood by many as a purveyor of prurient 'soft porn' seduction, his art has been much maligned." Notice, for example, that "the best elements of his paintings were usually the accessories, including drapery, flowers, fur and marble. These echoes of real life are the most convincing … While his faces are usually painted with great consideration, the hands and feet in his pictures are often given short shrift … Broadening the range of subjects would have enlivened and enriched his canvases immeasurably. But he continued to paint the 'same old, same old' instead of introducing more elements beyond peacock fans, flowers, variegated marbles."

In The Answer, a classically clad maiden sits thoughtfully in profile on a marble bench. Godward's technical craftsmanship is unsurpassed in his rendering of stone, especially the mosaic of multicolored granulites and impurities. The same dedication to detail can be observed in the folds of the maiden's dress, the bright pink of her tunic, and the green of her stole, vivifying the entire composition. Her dress gracefully fastens at her shoulder with three pearls, underscoring her femininity.

There is another Athenais of note from the Fifth Century CE. Aelia Eudocia Augusta (ca. 401-460), wife of Theodosius II, East Roman emperor, was born in Athens.

She was the daughter of the Sophist Leontius, from whom she received a thorough training in literature and rhetoric. The traditional story, told by John Malalas and others, is that she had been deprived of her small patrimony by the rapacity of her brothers, and sought redress at court in Constantinople. Her accomplishments attracted the attention of Theodosius' sister Pulcheria, who made her one of her ladies-in-waiting and groomed her to be the emperor's wife.

After receiving baptism and discarding her former name Athenais, for that of Aelia Licinia Eudocia, she was married to Theodosius on June 7, 421; two years later, after the birth of her daughter Licinia Eudoxia, she received the title Augusta. The new empress repaid her brothers by making Valerius a consul and later governor of Thrace and the other, Gesius, prefect of Illyricum.

Other, more contemporary historians like Socrates Scholasticus and John of Panon, confirm many of these details, but omit all mention of Pulcheria's participation in Eudocia's marriage to her brother. This makes other details of Eudocia's activities more understandable, as for example, using her substantial influence at court to protect pagans and Jews.

In the years 438-439 she made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and brought back several precious relics; during her stay at Antioch she addressed the senate of that city in Hellenic style and distributed funds for the repair of its buildings. On her return her position was undermined by the jealousy of Pulcheria and the groundless suspicion of an intrigue with her protégé Paulinus, the master of the offices.

After the latter's execution (440) she retired to Jerusalem, where she was accused of the murder of an officer sent to kill two of her followers, for which act she suffered the loss of some of her imperial staff. Nevertheless she retained great influence; although involved in the revolt of the Syrian Monophysites (453), she was ultimately reconciled to Pulcheria and readmitted into the Orthodox Church. She died at Jerusalem on October 20, 460, having devoting her last years to literature.

The model for Cleonice is depicted in profile, like the medieval portrait prototype. Her pink dress, bound with a green scarf, makes a contemporaneous appearance in Absence makes the heart grow fonder (1912) and Le Billet Doux (1913) - both full-length compositions girl herself, with her light-colored hair, most closely resembles the sitter in The Beldevere, for which Godward won a gold medal in the 1913 Rome Internationale exhibition.

Godward moved to Rome in the summer of 1912. It was rumored that his return was precipitated by the departure of a favored Italian model for her homeland. The artist set up his studio in the Villa Strohl-Fern, situated on Monti Parioli - dubbed the 'English Hill'. It had a large garden filled with antique sculpture and formed the perfect backdrop for some of his greatest artistic achievements.

Clodia was married as a young girl to Lucullus (divorced ca. 66 BC after friction between him and her brother Publius), then to Quintus Caecilius Metellus Celer, her first cousin. The marriage was not a happy one. Clodia engaged in several affairs with married men and slaves, becoming at the same time a notorious gambler and drinker. Arguments with Metellus Celer were constant, often in public situations. When Metellus Celer died in strange circumstances in 59 BC, Clodia was suspected of poisoning her husband.

As a widow, Clodia became known as a merry one, taking several lovers, including possibly the poet Catullus. Clodia maintained several other lovers, including Marcus Caelius Rufus, Catullus' friend. This particular affair would cause an immense scandal. After the relationship with Caelius was over in 56 BC, Clodia publicly accused him of attempted poisoning. The accusation led to a murder charge and trial. Caelius' defence lawyer was Cicero, who took a harsh approach against her, recorded in his speech Pro Caelio. Cicero had a personal interest in the case, as her brother Publius Clodius was Cicero's most bitter political enemy. Among other things, Clodia was accused of being a seducer and a drunkard in Rome and in Baiae, as well as committing incest with her brother Publius. Cicero insinuated that he "would attack Caelius' accusers still more vigorously, if I had not a quarrel with that woman's (Clodia's) husband - brother, I meant to say; I am always making this mistake. At present I will proceed with moderation... for I have never thought it my duty to engage in quarrels with any woman, especially with one whom all men have always considered everybody's friend rather than any one's enemy." He declared her a disgrace to her family and nicknamed Clodia the Medea of the Palatine. (Cicero's marriage to Terentia suffered from Terentia's persistent suspicions that Cicero was conducting an illicit affair with Clodia.)

After the trial of Caelius, in which Caelius was found not guilty, little or possibly nothing is heard of Clodia, and the date of her death is unknown. There is some difficulty in identifying Roman women due to the lack of female personal names. Either this Clodia or a sister was still alive in 44 BC.

The poet Catullus wrote several love poems concerning a frequently unfaithful woman he called Lesbia, identified in the mid-second century AD by the writer Apuleius as a "Clodia." This practice of replacing actual names with ones of identical metrical value was not uncommon in Latin poetry of that era. In modern times, the resulting identification of Lesbia with Clodia Metelli, based largely on her portrayal by Cicero, is usually treated as accepted fact.

The Sparrow is one of the Clodia/Lesbia poems of Catullus.

Sparrow, favorite of my girl,

with whom she is accustomed to play, whom she is accustomed to hold in her lap,

for whom, seeking greedily, she is accustomed to give her index finger

and to provoke sharp bites.

When it is pleasing for my shining desire

to make some kind of joke

and a relief of her grief.

I believe, so that her heavy passion may become quiet.

If only I were able to play with you yourself, and

to lighten the sad cares of your mind.

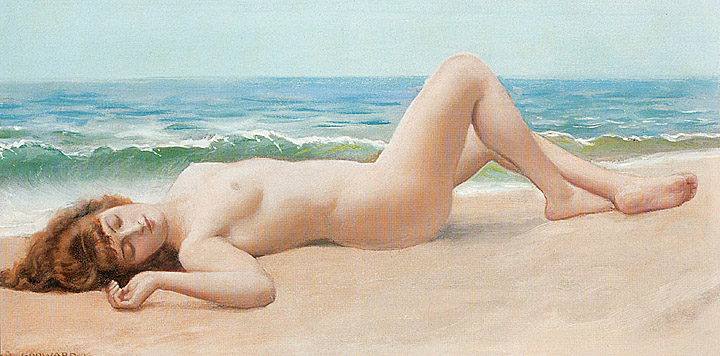

One is a small study of a nude woman on the beach, Nu Sur La Plage. Even at this late date in his life, Godward was willing to paint "private" pictures for himself. Another is a slightly haunting half-length entitled Ismene, notable for its strong cast shadow against a marble wall. The third one was Contemplation.

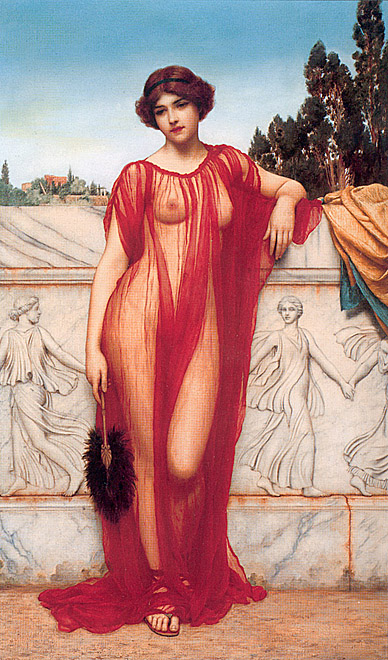

The New Perfume illustrates Godward's strengths and weaknesses. The table with griffin tripods and the folding stool are studio props, positioned to contrast with the variegated marble floor and wall. The figure of the woman, in a deep-red diaphanous robe, exhibits the influence of Leighton in its meticulous folds. The eroticism of the canvas is suggested by the woman's naked breast, where she will be applying the perfume. In its use of color the canvas has merit, but the specious recreation of a domestic interior is neither convincingly detailed nor archaeologically correct in the manner of Tadema. This welding of Tadema and Leighton in Godward is a potentially beautiful but also a hazardous experiment.

Personally I don't think he was doing that - Senex Magister.

The features of the lovely dark-haired model who is the subject of Crytilla appear in many of Godward's paintings of this period when he was settled at his Fulham Road Studio in Kensington. She appears in The Tambourine Girl of 1906, Ismenia of 1908, A Grecian Girl of 1908 and Bellezza Pompeiana of 1909. Her name is not known but it is likely that, like virtually all of Godward's models, she was a professional and may have been introduced to Godward by a fellow artist. Other models such as Ethel Warwick, Florrie Bird and the Pettigrew sisters who posed for Godward in the 1890s were very well known models who made their reputations through artist's recommending their services.

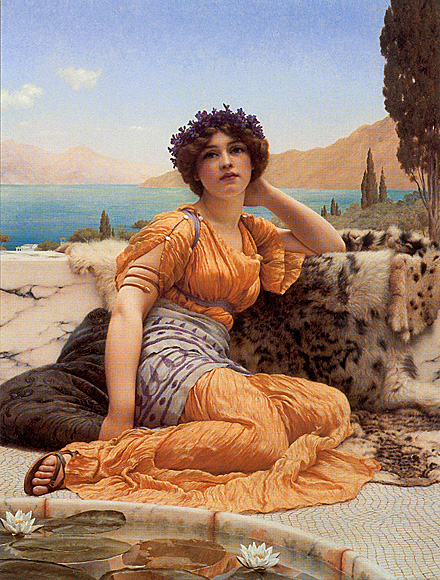

With violets wreathed and robe of saffron hue demonstrates Godward's skill through the naturalistic rendering of a wide variety of textures such as fabric, marble and flesh. Indeed, it is the very tangibility of the floating lily pads, soft fur and smooth cool stone that led Professor Vern Swanson to praise this as a work 'in which all the stops have been pulled. There is no demure sedateness here, only the artist blinding with his virtuosity'. The artist clothes the model in his favorite color combination of purple and yellow, only serving to enhance the comparison to Ionian Dancing Girl, which was exhibited at the New Gallery in 1902 and features on the cover of Professor Swanson's catalogue raisonnée.

The ancient Greeks considered the violet a symbol of fertility and love; they often used it in love potions and Pliny recommended that a garland of violets be worn about the head to ward off headaches and dizzy spells. The present model sits informally in a relaxed pose and gazes dreamily into the distance, perhaps substantiating the emblem of love that adorns her hair.

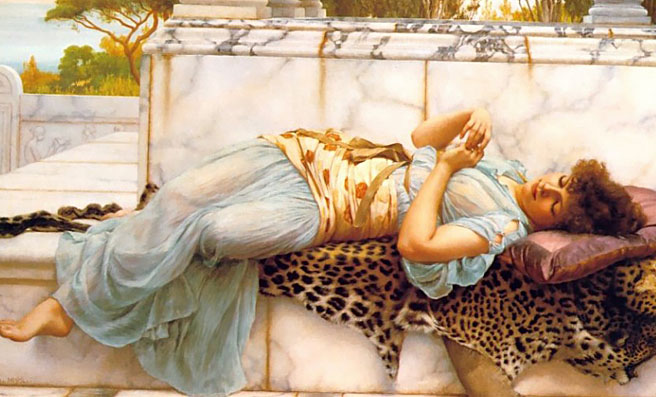

For over half a century after the continued excavations of Pompeii began in 1748, artists were fascinated with Greek and Roman life. John William Godward painted many scenes like this one of idealized beauties in calm, often sterile environments. In this painting, the figure of Repose is arranged seductively, with her breast and nipple showing through the thin material of her dress. But there is something distinctly untouchable about these women; they do not engage the viewer with an inviting gaze nor solicit personal contact. Like their antique setting, they possess a monumental, marmoreal quality, resembling Greek statues frozen in time.

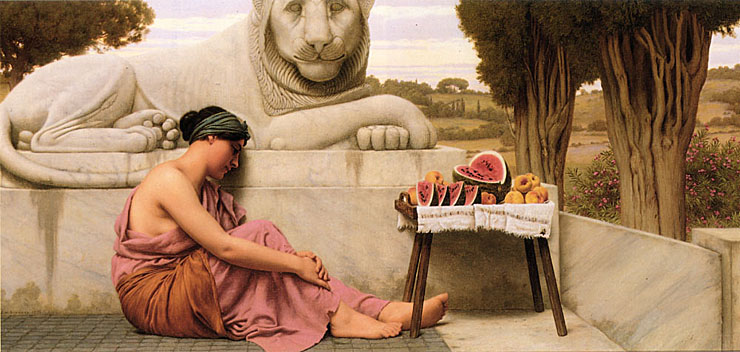

Godward's interest in still life and landscape was kindled by his residence in Italy. Whereas flowers and snippets of trees over marble walls had characterized his earlier work, he now began to more fully employ landscape and fruit elements. The lovely but forlorn fruit vendor contrasts vividly in color and stylization with the impassive figure of the stone lion sculpture. Godward often posed his models beside sculpture, usually bas-relief, almost as a counter point to his monumental figures."

In the present picture, Godward has reproduced one of a pair of fourth century B.C. Egyptian granite lions now in the Museo Gregoriano Egizio in the Vatican. It is likely that Godward saw these incredible sculptures in Italy during the seven years he spent there. The artist made some modifications; the stone has been transmuted from granite to marble, and Godward chose not to reproduce the hieroglyphic inscription.

Rather than continue his misery and see his art suffer through a diminished ability to paint, the artist committed suicide on Wednesday the 13th of December 1922. A hapless victim of his own personality, unable to make his way in a hostile world, Godward simply ended it all. Only the newspaper report of his death signaled the end of his brilliant career:

FULHAM GAZETTE

ARTIST DEAD BEFORE BLANK CANVAS: AMAZING GAS TRAGEDY

With his head lying in a packing case and his mouth touching the turned-on jets of a gas-ring, Mr. John William Godward, an artist in oils, aged 62, was found dead on Wednesday night in his studio at Fulham. The studio is at the rear of a house 410 Fulham Road, Fulham, where his brother and sister-in-law live.

He was an artist of some ability and a letter from a West End firm of art dealers, dated December 1, showed that he had recently sold them a picture entitled, "Contemplation" for the sum of £125. He was last seen alive on Wednesday morning having breakfast in his studio, where he lived alone.

A blank canvas found on his easel after the discovery of his death suggested that he was about to begin work on another picture. At six o'clock on Wednesday evening, when the brother, Mr. C. A. Godward, returned from business, he went into the studio to ascertain why it was in darkness. Pinned on an inner door he found the letter from the West End firm, enclosing the cheque.

This letter was pinned with the face against the door, and on the back of it was [the] word, "GAS" in the deceased handwriting. Entering a small room where the artist kept a wash-hand basin and a gas-ring, the brother found the artist lying dead. A coat was wrapped round the head apparently to confine the fumes.

The family was devastated. Nothing like this had ever happened to any Godward they knew. They felt disgraced before their peers as much as sorrow for their dead son and brother. The young married couple, Cuthbert and Ivy Godward, had lived in No. 412 since 1921. Ivy did not know that it was a suicide. She was told that something went wrong with the gas stove and he suffocated in the fumes. This denial was challenged by several newspaper notices.

Because it was a suicide an inquest was held enquiring after John William's death. The inquest for the sub-district of North East Fulham on December 16th was conducted by H. R. Oswald, Coroner for London. It is from this report that most of what we know about his last months is revealed. Typical of most suicides, there were warning signals from the victim. He had said, that a man shouldn't live beyond the age of sixty. The suicide took place shortly thereafter. The transcript of that inquest was reported in the Fulham Gazette:

60 YEARS OLD ENOUGH FOR A MAN: ASTONISHING THEORY OF A FULHAM ARTIST: FOUND DEAD WITH HEAD IN PACKING CASE:

Should a man live after he attains the age of 60? A Fulham artist who committed suicide and who suffered acutely from insomnia who had just turned 60 years declared before his death that was the limit for a man to live.

The tragedy was extremely dramatic as the deceased had just prior to his demise sold a painting and had the day previous sent birthday greetings to a brother.

The deceased was John William Godward, aged 61, who lived at 410 Fulham Road, Walham Green. An inquest was held by Mr. H. R. Oswald the West London Coroner, at the Fulham Coroner's Court on Saturday.

The brother of deceased, Charles Arthur Godward, a fire insurance official, living at the same address, said that his brother had been a very reserved man and lived entirely alone. On the Wednesday morning Witness [C.A. Godward] had seen him in the Garden when he seemed all right. As far as he knew deceased had not financial worries or troubles of any kind. On the previous Sunday deceased had asked him to send a telegram to his mother stating that he would not be able to go and see her as he was not feeling well.

Witness [C. A. Godward] asked him if he would have some lunch with him but he declined and witness told him if there was anything he wanted he was to let him know. There was a speaking tube between the house and deceased studio at the bottom of the garden about 40 ft away. When witness arrived home about half past five on Wednesday evening he was informed that deceased's studio door had been open all day and that the baker's boy, when he called, had been unable to make anyone hear at deceased's place. Witness thereupon went to the studio to investigate and found both doors open.

The Discovery

He [C. A. Godward] called his brother but could get no answer. It was dark so he returned to the house for some matches. He afterwards found pinned on the lavatory door a piece of paper with the word "GAS" on it in deceased's handwriting. He got a bicycle lamp and entering the lavatory found his brother lying on the floor with a dressing gown over his head. The place was full of gas which was escaping from a gas ring, and witness turned off the tap. He explained that the lavatory was used by deceased as a washing place and a scullery combined. Deceased was lying on his side and his head was in a packing case with the gas ring underneath.

Witness added that his brother had suffered for some time from insomnia and acute dyspepsia and was not a happy man at all. He would often be out in the garden till two or three o'clock in the morning because he could not sleep.

The Coroner: He was [of] a very melancholy nature?

Witness: Yes.

Marietta Avico, an artist's model of Tottenham Street, Tottenham Court Road, said that she had known deceased about eighteen months. He had very bad health and she last saw him alive on Tuesday, when he appeared to be in pain and was suffering from stomach trouble. He used to walk in his studio at nights unto 2 or 3 in the morning as he could not sleep.

The Coroner: Did he ever take stuff to produce sleep?

Witness (M. Avico): Yes, he bought some medicine to help him to sleep at night.

Continuing, witness said that deceased told her on the Tuesday that she need not come again until the following Tuesday, and he had made the remark that 60 was old (enough) for a man to live.

Dr. J. Bradshaw said that when he was called to the house deceased must have been dead several hours. Dr. C. T. Pearsons, Medical Superintendent of the Fulham Infirmary detailed the result of his post-mortem exam and said that death was due to coal gas poisoning.

The Coroner returned a verdict of "Suicide whilst of unsound mind."

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.