John Frederick Kensett

American Painter and Printmaker

1816 - 1872

John Frederick Kensett was an American artist and engraver. He attended school at Cheshire Academy, and studied engraving with his immigrant father, Thomas Kensett, and later with his uncle, Alfred Dagget. He worked as engraver in the New Haven area until about 1838, after which he went to work as a bank note engraver in New York City.

In 1840, along with Asher Durand and John William Casilear, Kensett traveled to Europe in order to study painting. There he met and traveled with Benjamin Champney. The two sketched and painted throughout Europe, refining their talents. During this period, Kensett developed an appreciation and affinity for 17th century Dutch landscape painting. Kensett and Champney returned to the United States in 1847.

After establishing his studio and settling in New York, Kensett traveled extensively throughout the Northeast and the Colorado Rockies as well as making several trips back to Europe.

Kensett is best known for his landscape of upstate New York and New England and seascapes of coastal New Jersey, Long Island and New England. He is most closely associated with the so-called "second generation" of the Hudson River School. Along with Sanford Robinson Gifford, Fitz Hugh Lane, Jasper Francis Cropsey, Martin Johnson Heade and others, the works of the "Luminists", as they came to be known, were characterized by unselfconscious, nearly invisible brushstrokes used to convey the qualities and effects of atmospheric light. It could be considered the spiritual, if not stylistic, cousin to Impressionism. Such spiritualism stemmed from Transcendentalist philosophies of sublime nature and contemplation bringing one closer to a spiritual truth.

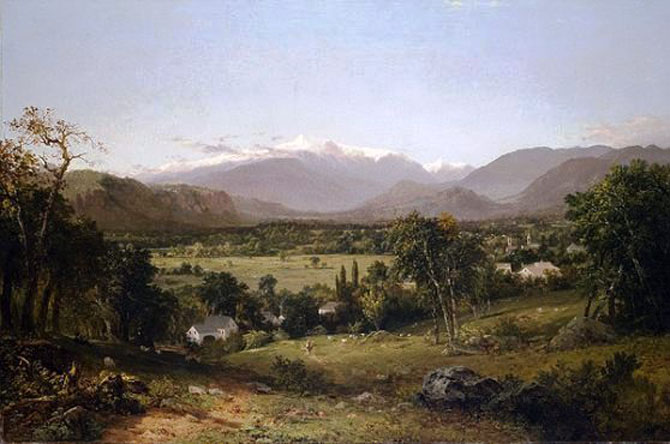

In 1851 Kensett painted a monumental canvas of Mount Washington that has become an icon of White Mountain Art. "Mount Washington from the Valley of Conway" was purchased by the American Art Union, made into an engraving by James Smillie, and distributed to 13,000 Art Union subscribers throughout the country. Other artists painted copies of this scene from the print. Currier and Ives published a similar print in about 1860. This single painting by Kensett helped to popularize the White Mountain region of New Hampshire.

Mount Washington from the Valley of Conway

John Frederick Kensett's "Mount Washington from the Valley of Conway" majestically illustrates 19th-century America's hopes and ambitions with convincing realism and sentiment. A rocky dirt path leads into a nest of houses, a church and a few town buildings whose rooftops and steeples peak out from a sheltering valley of trees and farmlands. Resting below the massive Mount Washington off in the distance, the valley is protectively enclosed by the mountains of the Appalachian Mountain range. This hilltop panoramic view personalizes the painting, giving the viewer a physical and spiritual sense of coming home. A diminutive figure can be seen reclining under a shady tree while tending to wandering sheep that dot the hilltop. Another figure is walking slowly along further down the path, as if taking in the scene around him.

Harmonious interaction between man and nature is depicted within Kensett's panoramic landscape. Rather than presenting an untamed or conquered landscape, Kensett promotes the rewards of virtuous labor and industrious, respectful attention to nature. Mount Washington exemplified the virtues set by the American Art-Union in the mid 19th century. Founded in 1838 to "promote the permanent and progressive advance of American Art," the Art-Union was possibly the most influential art institution of its day. American landscape artists were encouraged to aspire to a large measure of literal truth as well as patriotic sentiment, "something that will awaken our sympathies and strengthen the bond that binds us to our home."

Kensett's fidelity to detail, heroism, and patriotism was lauded by the Art-Union and well received by the American public. This vision of orderly paradise, however, reveals nothing of the political and social turmoil ripping the nation at this time in history. The flourishing slave trade in the nation's capitol was increasingly noxious to office-holders in the North; the absence of effective fugitive-slave policies was aggravating to the South and talk of secession was spurring them on toward Civil War. Technological advances such as the railroad and steam power were transforming America from an agrarian society to an industrial economy.

By 1850 the population had exceeded 23 million, with citizens spanning the entire continent and huge numbers of immigrants changing the demographic and political profiles of entire regions. The detailed realism with which Mount Washington is painted makes the view of Eden more persuasive; its appeal was sentimental, evoking images of a more innocent time. Kensett's placement in the Art-Union's annual exhibition was perhaps intended to shore up a Jeffersonian vision of America, chosen to serve as the public voice of its culture as well as to embody stability to a country in turmoil.

Quoted From: Walker Art Center - The Shock of the View - John Frederick Kensett

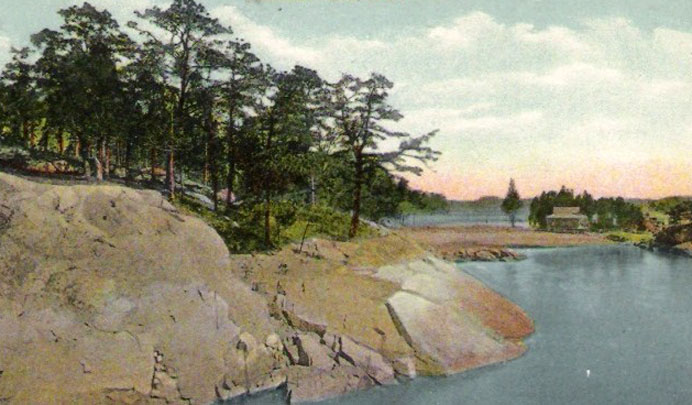

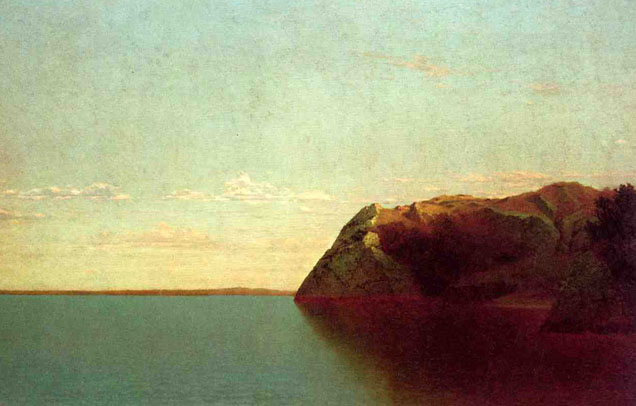

Kensett's style evolved gradually, from the traditional Hudson River School manner in the 1850's into the more refined Luminist style in his later years. By the early 1870's Kensett was spending considerable time at his home on Contentment Island, on Long Island Sound near Darien, Connecticut.

Postcard - Darien, CT - Contentment Island: 1914

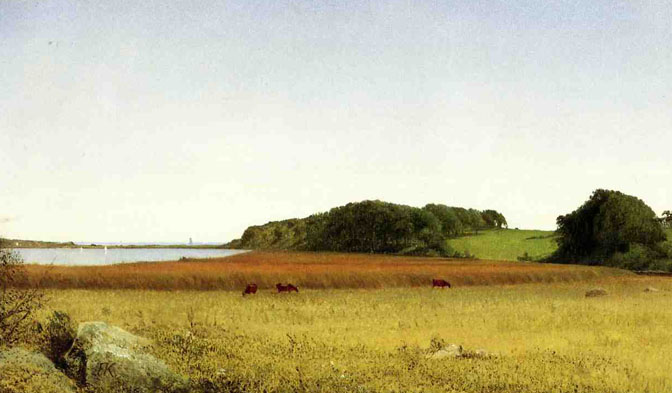

It was during this time that Kensett painted some of his finest works. Many of these were spare and luminist seascapes, the prime example being Eaton's Neck, Long Island (1872) now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Neck, Long Island: 1872

Eaton's Neck is unusual if not unique in Kensett's oeuvre for its Long Island subject. On the other hand, recording the site, on Long Island's north shore near Huntington in Suffolk County, would have required perhaps an hour's sail or less across the Long Island Sound from Kensett's studio off Darien, Connecticut. Like virtually all the paintings found in the studio at the artist's death in 1872, Eaton's Neck is unsigned and undated, and its state of completion is, at best, ambiguous. Kensett, for instance, worked the shoreline foliage into a state of finish comparable to works that he signed and sold, but the apparent sailboats punctuating the distant horizon are plotted without being fully articulated, as they are in finished works. Still, given the reductive character of almost all Kensett's late paintings, this synthesis of uninflected land, water, and sky engages the spectator equally with, if not more than, any in the same gallery by the artist or his Hudson River School colleagues.

Quoted From: John Frederick Kensett: Eaton's Neck, Long Island - The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The artist was widely acclaimed and financially successful during his lifetime. In turn, he was generous in support of the arts and artists. He was a full member of the National Academy of Design, the founder and president of the Artists' Fund Society, and a founder and trustee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Kensett contracted pneumonia (perhaps during the attempted rescue of Mary Lydia (Hancock) Colyer, the wife of his friend and fellow artist Vincent Colyer in Long Island Sound) and died of heart failure at his New York studio in December 1872.

From: Wikipedia

From: John Frederick Kensett Online

Various Works of John Frederick Kensett

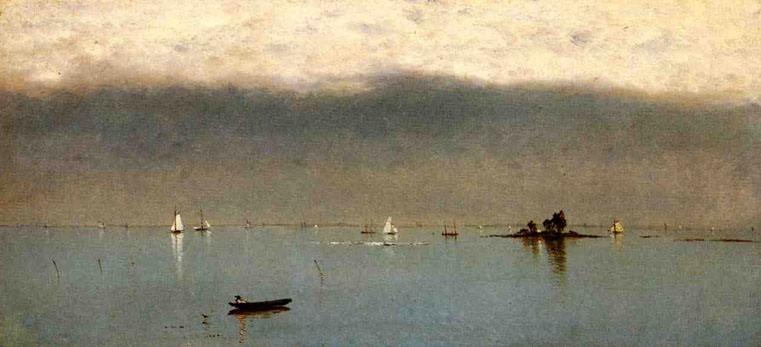

A Foggy Sky: Date Unknown

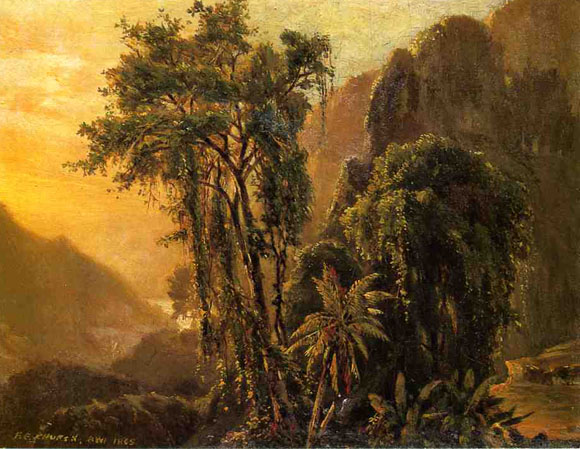

A Glimpse of the Caribbean Sea from the Jamaica Mountains: Date Unknown

A Newport Afternoon: Date Unknown

A Quiet Day on the Beverly Shore: Date Unknown

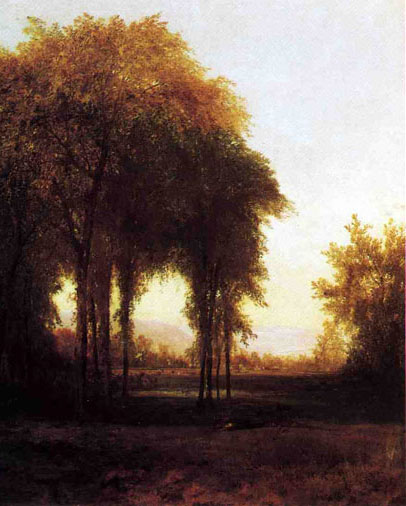

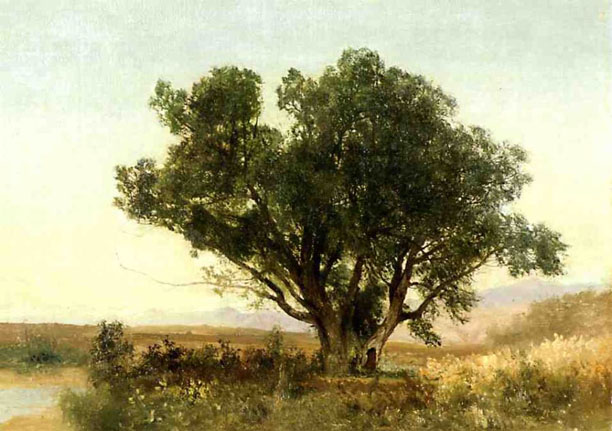

A Study of Trees: Date Unknown

A View of Mansfield Mountain: 1849

Artists of the Hudson River School often made pencil or oil sketches out-of-doors and later used them in the studio as a guide to create finished works. Here, John Kensett depicted an artist painting a view popular with tourists and artists: Mount Mansfield in the Green Mountains of Vermont and its pastoral, sun-filled valley below. With the invention of the steamboat, the expansion of the railway, and improved roads, artists and other nature tourists had easier access to glorious sites like this one.

Quoted From: MFAH/Art Search/Search the MFAH Art Database

A View of Niagara Falls: Date Unknown

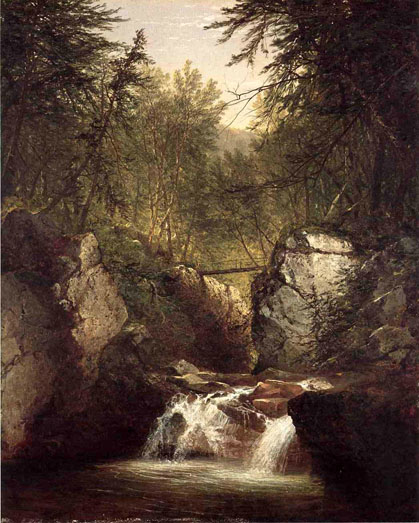

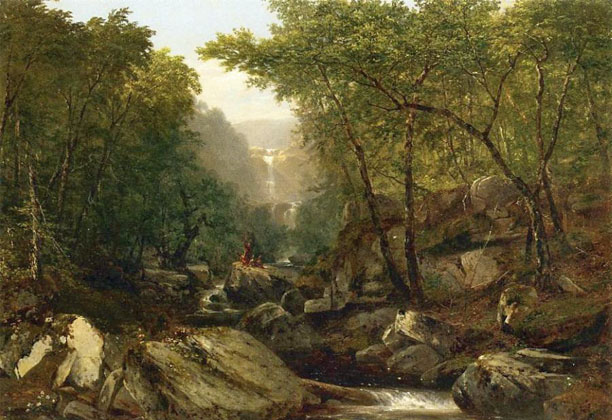

A Woodland Waterfall: ca 1855

Adirondack Scenery: 1854

Along the Hudson: 1852

Along the Hudson: Date Unknown

Along the Shore: Date Unknown

An Inlet of Long Island Sound: ca 1865

At Pasture: ca 1844-45

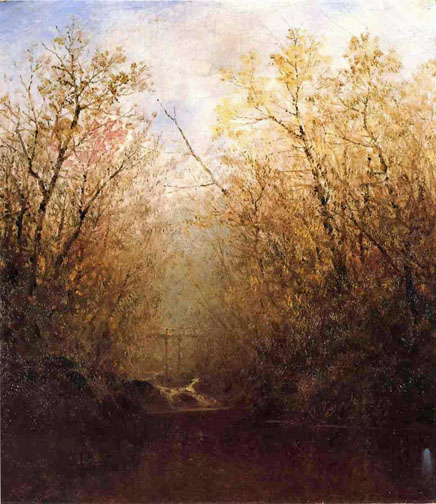

Autumn Landscape: Date Unknown

Autumn River Scene: Date Unknown

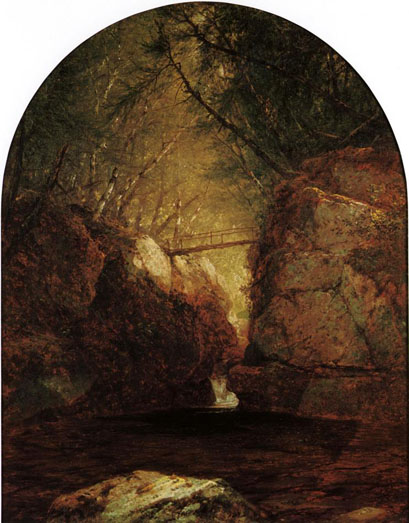

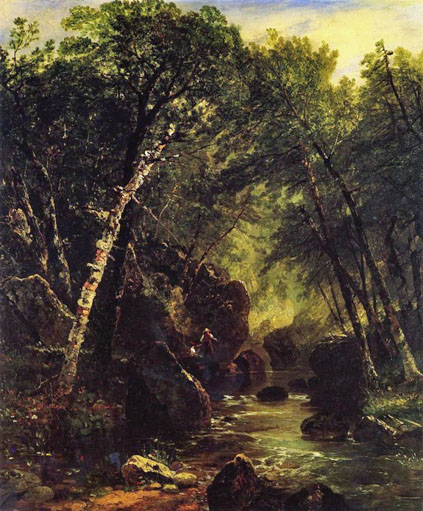

Bash Bish Falls: 1855

Bash Bish Falls: ca 1855-60

Bash Bish Falls: Date Unknown

Bash Bish Falls: Date Unknown

Bash Bish Falls: 1857

Bash Bish Falls

The forest and gorge surrounding Bash Bish Falls in South Egremont, Massachusetts, were considered in the mid-nineteenth century to be one of the most picturesque pleasure-tour destinations in the Berkshire Mountains. The falls themselves were described in The Cray-on as "one of the wildest and most beautiful cascades in the country." They became John Frederick Kensett's favorite among the American waterfalls that he visited and painted during the 1850's.

Kensett painted Bash Bish Falls at least five times. This version is most closely related to a small oval canvas (1851, Lyman Allyn Art Museum, New London, Conn.) and to a larger painting made for his friend, James Suydam (1855, National Academy of Design). The Butler Institute's version is unfinished and therefore the date is uncertain, but it may have been originally intended for Suydam, as both paintings were probably once the same size. The small Bash Bish Falls that Kensett painted in 1851 shows a pair of boulders in the middle ground linked by a foot bridge, a cataract below that, a pool of water in the foreground and, as a backdrop, a thicket of trees. Kensett completed the first composition in the year that he painted a number of views of Niagara Falls, rendering the Berkshire falls as Niagara's compositional opposite. Far from a powerful, horizontal waterfall along an open horizon as in Niagara Falls, the Bash Bish Falls are made delicate, vertical, and closed-in. Later, Kensett returned to Bash Bish Falls to paint another version of them, where he presented the cascade as a grand panorama, which contrasts with this work's concentration on their more sheltered, less spectacular, aspect. It appears that Kensett painted the Butler Institute's canvas to enlarge the view he had painted in 1851. As he did so, he perhaps decided that moving the cataract to the center foreground, in place of the still water, and giving greater variety to the boulders, rather than flattened profiles, would result in a livelier effect. Rather than over paint a composition already well progressed, a practice Kensett consistently avoided, he seems to have set the canvas aside to begin afresh on another of the same size, that is, the work presented to Suydam. In making the new version, he also altered a number of minor details as he saw fit, from the crevices in the boulders to the arrangement of the surrounding trees.

Bash Bish Falls reveals Kensett's willingness to give himself over to nature's detail and plunge deeply and irretrievably into the woodland interior. The composition is organized upon a series of receding horizontal Planes which makes the viewer lose all sense of deep space. The vertical format reins in the horizontal expanse of sky and, by decreasing the viewer's lateral eye movement, locks all attention into the center of the forest, where the viewer is forced to concentrate on the plethora of tree branches, scrub, rocks, and moss. Such a rendering is indebted to the precedent of the on-site oil sketch, particularly those of Asher B. Durand, exemplified by such works as Interior of a Wood (ca. 1850, Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Mass.) and Study from Nature (c. 1855, The New-York Historical Society).

The Butler institute's version of Bash Bish Falls presents an opportunity to see the underpinnings of Kensett's animated painting technique of the 1850's. Still exposed is much of the thin, reddish priming applied to his canvases before adding the highlights and shadows. Kensett applied the finishing highlights and darkest tones together, working from the top of the canvas down. To paint over his reddish priming he employed an elaborate scumbling technique. With brushes of various degrees of fineness, he scrubbed in layers of very thin paint, which allowed him to create a richly textured image with minimal build up of the canvas surface.

Kensett was the most influential member of the second generation of the Hudson River School of landscape painters. He began his career as a commercial engraver, studying landscape painting in his spare time. He went abroad to study in 1840 and after his return to New York in late 1847, his career as a landscape painter quickly flourished. He is best known for his depictions of the mountains and coastal regions of New York and New England. In contrast to his contemporaries, Albert Bierstadt and Frederic E. Church, Kensett's work was distinguished by an enduring modesty. Avoiding over scaled and overly dramatic scenery, he earned great praise for his sensitivity to modest views of nature and his fidelity to its most minute detail.

DIANA STRAZDES

Quoted From: JOHN FREDERICK KENSETT 1816

Bay of Newport: 1863

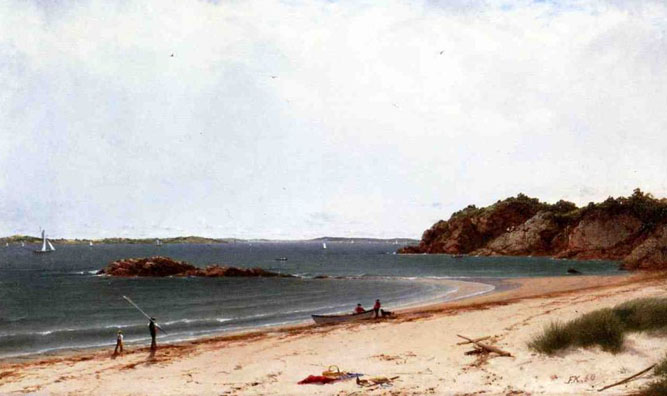

Beach at Newport: ca 1869-72

Beach at Newport: Date Unknown

Beacon Rock, Newport Harbor: 1857

![]()

Black Mountain, Lake George: Date Unknown

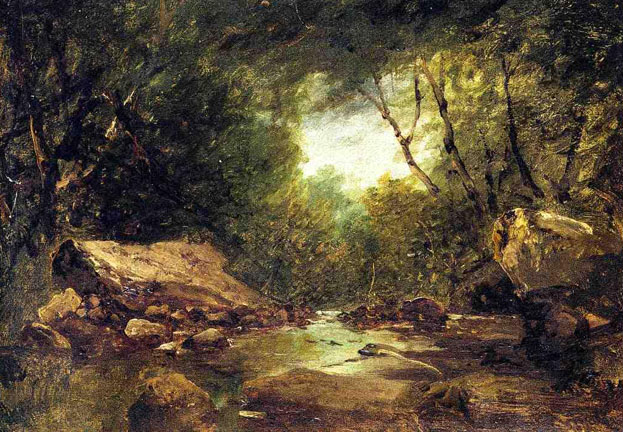

Brook in the Catskills: Date Unknown

Camel's Hump from the Western Shore of Lake Champlain: 1852

Cascade near Lake George: Date Unknown

Catskill Mountain Scenery: 1852

Clearing Off: Date Unknown

Coast Scene with Figures: 1869

Coast Scene: 1854

Conway Valley, New Hampshire: 1854

Eagle Rock - Manchester, Massachusetts: 1859

Eagle Rock, Manchester, Massachusetts: 1859

Eastern Mountain Lake: 1869

Entrance to Newport Harbor: 1855

Farm at the Edge of the Forest: Date Unknown

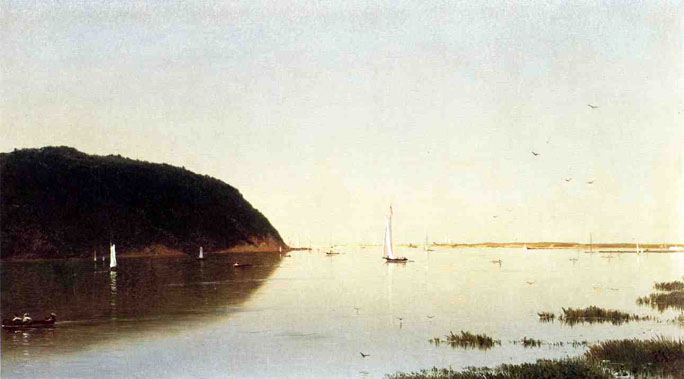

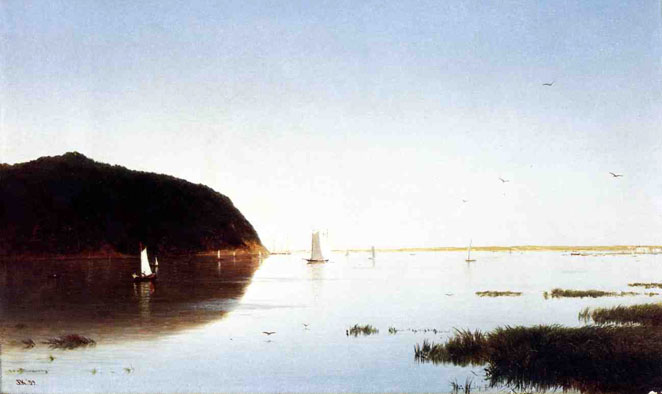

Fish Island from Kensett's Studio on Contentment Island: 1872

Forty Steps, Newport, Rhode Island: 1860

Franconia Notch, New Hampshire: 1871

Hudson River: Date Unknown

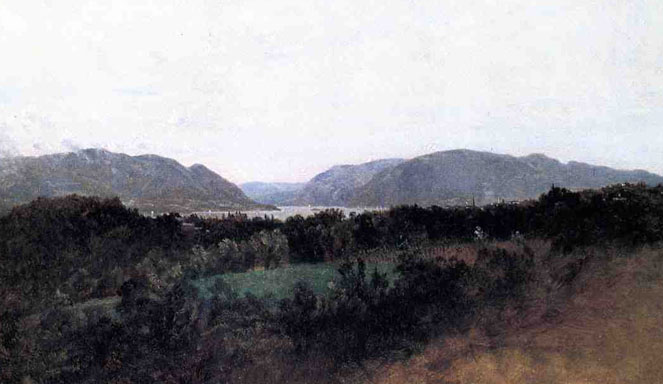

Hudson River Looking towards Haverstraw: ca 1850-59

Hudson River Scene: 1857

Hunters on a Riverbank: 1850

Lake George: 1869

Lake George: 1870

Lake George: ca 1860-69

Lake with Boaters: 1858

Lakes of Killarney: 1857

Landscape

(aka A Reminiscence of the White Mountains): 1852

_1852.jpg)

Landscape: Date Unknown

Landscape: Date Unknown

Landscape with Figure: Date Unknown

Landscape with Sea Paradise Rocks, Newport, Rhode Island: ca 1865

Landscape with Waterfall: Date Unknown

Late Summer: Date Unknown

Lily Pond, Newport, Rhode Island: ca 1865

Long Neck Point from Contentment Island, Darien, Connecticut: ca 1870-72

Marine off Big Rock: 1864

Morning: Date Unknown

Mount Chocorua: 1857

Mount Chocorua: 1864-66

Mountain Lake: 1866

Nahant: 1850

Narragansett Coast: ca 1865-70

Narragansett Coast: Date Unknown

Near Newport: Date Unknown

Near Newport, Rhode Island: 1872

New England Coastal View with Figures: 1864

New England Composition Scenery: Date Unknown

New England Sunrise: 1859

New Hampshire and School's Out: 1850

Newport Coast: ca 1865-70

Newport Harbor and the Home of Ida Lewis: ca 1871

Newport Rocks: 1872

Niagara Falls and the Rapids: ca 1851-52

Niagara Falls: ca 1851-52

October Day in the White Mountains: 1854

On the Beverly Coast, Massachusetts: 1863

On the Coast: 1870

On the Coast, Beverly Shore, Massachusetts: 1872

On the Connecticut Shore: 1871

On the Saint Vrain Colorado Territory: 1870

Paradise Rocks, near Newport: 1859

Paradise Rocks, Newport: ca 1865

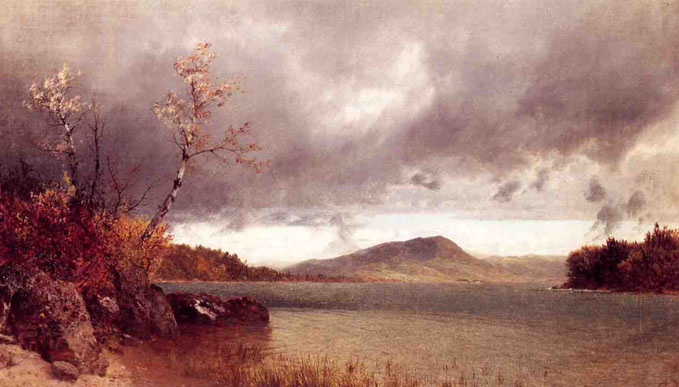

Passing Off of the Storm: 1872

Path over the Field, A Recollection of the Hudson: 1852

Point of Rocks, Newport: Date Unknown

Reminiscences of the Catskill Mountains: 1853

Rocks at Newport: Date Unknown

Shrewsbury River: 1858

Shrewsbury River, New Jersey: 1859

Shrewsbury River: 1860

Storm Western Colorado: 1870

Study on Long Island Sound at Darien, Connectucut: 1872

Summer Day on Conesus Lake: 1870

Sunrise among the Rocks of Paradise, Newport: 1859

Sunset on the Sea: 1872

Sunset over Lake George: 1867

The Catskills: 1859

The Front Range, Colorado: Date Unknown

The Hemlock: 1870

The Langsdale Pike: 1858

The Langsdale Pike: 1860

The Mountain Stream: 1845

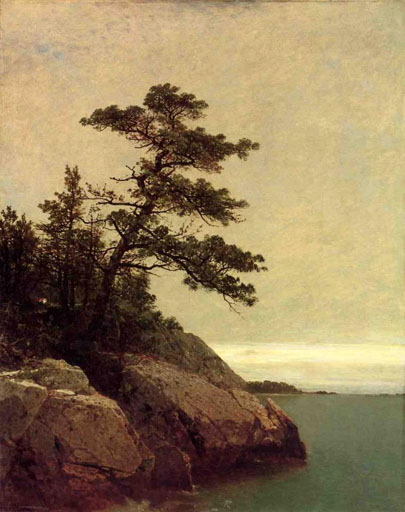

The Old Pine, Darien, Connecticut: 1872

The Shrine - A Scene in Italy: 1847

The Still Pool: Date Unknown

Trotter's Spring, Colorado: 1871

Trout Fisherman: 1852

Twilight After a Storm: Date Unknown

Twilight on the Sound, Darien, Connecticut: 1872

Upper Mississippi: 1855

View from Cozzens Hotel near West Point: 1863

View from Richmond Hill: 1843

View of Lake George: 1872

View of Mount Mansfield: 1872

View of Rhode Island: 1858

View of the Beach at Beverly, Massachusetts: 1860

View of the Shrewsbury River: 1853

View on the Hudson: 1865

Waterfall in the Woods with Indians: 1850

Watering Cattle: 1844

White Mountain Scenery: 1859

Windsow Woods: Date Unknown

Windsow Woods: Date Unknown

From: The Athenaeum

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.