1632 - 1675

Johannes Vermeer or Jan Vermeer was a Dutch Baroque painter who specialized in domestic interior scenes of ordinary life. His entire life was spent in the town of Delft. Vermeer was a moderately successful provincial painter in his lifetime. He seems to have never been particularly wealthy, perhaps because he produced relatively few paintings, leaving his wife and children in debt at his death.

Virtually forgotten for nearly two hundred years, in 1866 the art critic Thore Burger published an essay attributing 66 pictures to him (only 35 paintings are firmly attributed to him today). Since that time Vermeer's reputation has grown, and he is now acknowledged as one of the greatest painters of the Dutch Golden Age, and is particularly renowned for his masterly treatment and use of light in his work.

Relatively little is known about Vermeer's life. He seems to have been exclusively devoted to his art. The only sources of information are some registers, a few official documents and comments by other artists; it was for this reason that Thore Burger named him "The Sphinx of Delft". Vermeer became the subject of a biography by John Michael Montias: Vermeer and his milieu: a web of social history (Princeton, 1989), where the social history covers up for the elusiveness of the central character.

Johannes Vermeer was born in 1632, in the city of Delft in the Netherlands. The precise date of his birth is unknown but it is known that he was baptized on October 31, 1632, in the Reformed Church. Reynier Janszoon, his father, was a lower middle-class silk or caffa worker. In 1615 he married Digna Baltens, a woman from Antwerp. In 1620 Gertruy was born. In 1625 his father was involved in a fight with a soldier, who died from his wounds five months later. Around 1631 Reynier Jansz leased an inn, called the Flying Fox; Vermeer also started in that year to deal in paintings; as a sideline, he continued to work as a weaver. In 1641, when the lease ran out, his father bought a larger inn at the market square in Delft, named after the Belgian town, "Mechelen". Gertruy, who helped her parents, serving drinks and making beds, married a sought after framemaker in 1647. When Reynier Jansz died in 1652, Johannes Vermeer replaced his father as a merchant of paintings.

Despite the fact that he came from a Protestant family, he married in April 1653 a Catholic girl, named Catherina Bolnes in Schipluiden. It was an unlikely marriage: his future mother-in-law, Maria Thins was significantly wealthier. For Vermeer it was a good match and he converted to Catholicism shortly before their marriage. One of his paintings, The Allegory of Catholic Faith, (made between 1670 and 1672) reflects the belief in the Eucharist. It treats the concept of his adopted religion and it was probably made expressly for a Catholic patron or for a schuilkerk, or hidden church. Soon after their marriage, the couple left the Mechelen and moved in with Catherina's mother at Oude Langendijk, near the gate. Vermeer would live there with his wife and children for the rest of his life, producing paintings in the front room on the second floor. Vermeer and his wife had fourteen children in total: three sons and seven daughters, four were buried in an early stage, without having a name.

Vermeer was apprenticed as a painter, but it is not certain where he studied, nor with whom. It is generally believed that he studied in Delft and it is suggested that his teacher was either Carel Fabritius or likelier Leonaert Bramer. It is possible he taught himself or he had information from one of his father connections.

On December 29, 1653, Vermeer became a member of the Guild of Saint Luke, a trade association for painters. The guild's records, which indicate that he could not initially pay the admission fee, hint that Vermeer had financial difficulties. In later years he might have got a patron in the local art collector Pieter van Ruijven. In 1662 Vermeer was elected head of the guild and was reelected in 1663, 1670, and 1671, evidence that he was considered an established craftsman among his peers, and a respectable middle-class citizen. When the diplomat Balthasar de Monconys visited him in 1663 to see some of his work, he was sent to the baker, most probably Hendrick van Buyten, who owned one painting at that time.

In 1672 (the "Year of Disaster"), a severe economic downturn struck the Netherlands, when the French army under Louis XIV invaded the Dutch Republic, in what was later known as the Franco-Dutch War. Not only the French, but also the English fleet and two German bishops were attacking the country, trying to destroy the countries hegemony. Many people panicked and shops and schools closed. It took some years before the circumstances would improve. The collapse of the art-market damaged Vermeer's business both as a painter and an art dealer.

With a large family to support, Vermeer was forced to borrow money. In December 1675 Vermeer fell into a frenzy and died within a day and a half. In a written document Catharina Bolnes attributed her husband's death to the stress of financial pressures. She, having to raise eleven children, (underlined in the original) asked the High Court to allow her a break in paying the creditors.

The Dutch microscopist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, who sometimes worked for the city council, was appointed trustee. The house, with eight rooms on the first floor, was filled with paintings, (Vermeer did own three paintings by Fabritius), drawings, clothes, chairs and beds. In his atelier there were among rummage not worthy being itemized, two chairs, two painter's easels, three pallets, ten canvases, a desk, an oak pull table and a small wooden cupboard with drawers. Nineteen of Vermeer's paintings were bequeathed to his wife and her mother; Catherina sold two more paintings to the baker, in order to pay off the debts.

In Delft, Vermeer had been a respected artist, but he was almost unknown outside his home town, and the fact that a local patron, van Ruijven, purchased much of his output reduced the possibility of his fame spreading. Vermeer never had any pupils and his relatively short life, the demands of separate careers, and his extraordinary precision as a painter all help to explain his limited output. Vermeer worked slowly, probably producing three paintings a year.

Vermeer produced transparent colors by applying paint to the canvas in loosely granular layers, a technique called pointille (not to be confused with pointillism). No drawings have been securely attributed to Vermeer, and his paintings offer few clues to preparatory methods. David Hockney, among other historians and advocates of the Hockney-Falco thesis, has speculated that Vermeer used a camera obscura to achieve precise positioning in his compositions, and this view seems to be supported by certain light and perspective effects which would result from the use of such lenses and not the naked eye alone; however, the extent of Vermeer's dependence upon the camera obscura is disputed by historians.

There is no other seventeenth century artist who from very early on in his career employed, in the most lavish way, the exorbitantly expensive pigment lapis lazuli, natural ultramarine. Not only used in elements that are intended to be shown as appearance: the earth colors umber and ochre should be understood as warm light from the strongly-lit interior, reflecting its multiple colors back on to the wall.

This working method most probably was inspired by Vermeer's understanding of Leonardo's observations that the surface of every object partakes of the color of the adjacent object. This means that no object is ever seen entirely in its natural color.

A comparable but even more remarkable yet effectual use of natural ultramarine is in 'The Girl with a Wineglass' (Braunschweig). The shadows of the red satin dress are under painted in natural ultramarine, and due to this underlying blue paint layer, the red lake and vermilion mixture applied over it acquires a slightly purple, cool and crisp appearance that is most powerful.

Even after Vermeer's supposed financial breakdown following the so-called rampjaar (year of disaster) in 1672, he continued to employ natural ultramarine most generously, such as in 'Lady Seated at a Virginal.' This could suggest that Vermeer was supplied with materials by a collector, and would coincide with John Michael Montias' theory of Pieter Claesz van Ruijven being Vermeer's patron.

Vermeer painted mostly domestic interior scenes. His works are largely genre pieces and portraits, with the exception of two cityscapes.

His subjects offer a cross-section of seventeenth century Dutch society, ranging from the portraits of a simple milkmaid at work, to the luxury and splendor of rich notables and merchantmen in their roomy houses. Religious and scientific connotations can be found in his works.

It seems likely that we have here an Italianate copy after a not yet identified original by a minor Italian master. The numerous borrowings from other artists that were easily discovered by art critics point to a pasticcio more than to the youthful work of a potential great. Italian sources, such as the figure of Christ in the picture by Andrea Vaccaro (Naples, Pinacoteca Reggia di Capodimonte), the Christ in another painting by Alessandro Allori (Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum), or the gesture of the Christ's right arm in a work by Bernardo Cavallino (National Museum, Naples), join evident derivations from the Fleming Erasmus Quellinus (Musee des Beaux Arts, Valenciennes). This figure of Christ belongs to the repertory of Italian painters and was used in many studios in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

The painting is probably an Italianizing copy after a minor Florentine artist. Some connoisseurs believe that this copy was executed by an Italian in his customary technique. Others are inclined to admit that the painting could have been done by a northern artist, in close imitation of the Florentine original. The latter exists: it is by Felice Ficherelli (1605-69?) and belongs to a private collector in Ferrara. In any case, it is a mediocre painting. The main difference from the Florentine original is the cross in the hands of the saint, which was probably added at the request of a convent or church that had commissioned the work.

An attribution to Vermeer finds its sole basis in the two signatures; because neither style nor pictorial quality is anywhere close to the artistic level of Vermeer. It is extremely important to remember in this context, that false Vermeer signatures occur often and were probably affixed sometime during the eighteenth or nineteenth century. If such an inscription is two hundred years old, as compared with the age of roughly three hundred years for the painting, the period when it was painted becomes almost impossible to prove either way by so-called scientific methods.

The artist must have been deeply aware of the great tradition of the theme, the most famous painting being by Titian and the version based on Titian's by Rubens. Prints were in circulation at the time, so the artist might have seen them for example.

There is no relationship between this painting and other authentic works by the master, neither in the conception nor the execution. One has attempted to establish a connection between this work and the one by Dirck van Baburen from 1622, now in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. However, aside from the subject matter, the Dresden painting has nothing in common with the one in Boston. The latter seems to have been part of Vermeer van Delft's stock in trade and appears as such in two of his paintings. At one time, it must have been the property of his mother-in-law.

The fact that Vermeer van Delft was a dealer and thus owned a number of works by other masters does not necessarily imply that he took them as models for his own productions; even if he used some of them as background decorations in his paintings.

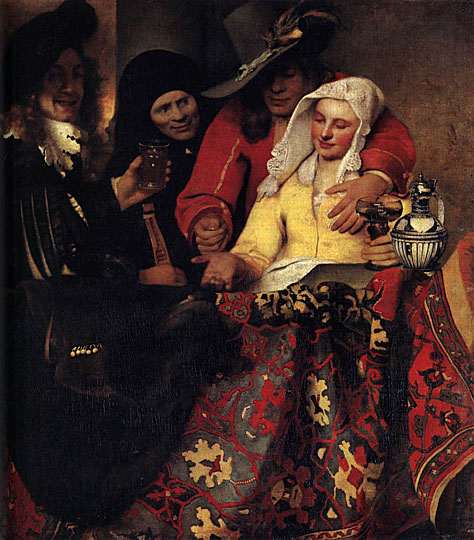

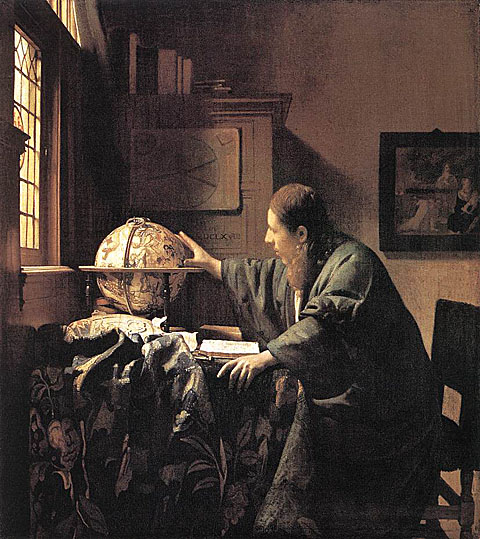

However, this painting is usually considered as a point of departure for an appraisal of Vermeer's achievement. There is very little indication of the interior and more action in it than there will be in the later paintings. The erotic subject, size and decorative splendor are all closely related to the Utrecht Caravaggisti painted a generation earlier. The chiaroscuro effect and the warm color harmony of reds and yellows also indicate a connection with works painted in the early fifties by Rembrandt and his followers; perhaps Maes, who had settled in nearby Dordrecht by 1653, was the conduit.

This painting is the earliest indisputable work by the master. Vermeer's earliest phase was Rembrandtesque. This can easily be ascertained from the rich and heavily impastoed pigments used in this painting. His subjects are always deceptively simple. He shows us in the left part of the composition a table covered with a glowing Oriental rug pulled up in front. On it is a Delftware plate with fruit, a white pitcher, and an overturned glass or wine glass in the foreground. At the far end of the table is a young woman asleep, her head resting on her propped-up right arm and hand; the left one lies negligently flat. To the right is the back of a chair, and in the distance a half-open door that allows the viewer to see into another room.

The theme goes directly back to Rembrandt. One of his drawings, 'A Girl Asleep at a Window', at the Tuffier Collection, Paris, shows a very similar pose. This, and the type of model, were also adopted by Nicolaes Maes in his Idle Servant, dated 1655, at the National Gallery, London, although there the maid sleeps on her left arm and hand. An identical stance can also be found in Maes's Housekeeper from a year later, 1656, at the art museum of Saint Louis. It has been suggested that Nicolaes Maes stayed in Delft after having left Rembrandt's studio, perhaps in 1653 or even later, to move to Dordrecht afterward. In any event, there were ample possibilities for Vermeer to have had access to Rembrandtesque drawings, from a possible stay in the Rembrandt studio to Leonard Bramer and Carel Fabritius. The handling of the light, as well as the deep coloring and heavy paste in the execution, derives from Rembrandtesque techniques of the early 1640s.

Technical examinations revealed that Vermeer made major changes in the course of execution. Thus, he initially put a man in the second room instead of the mirror, and a dog in the doorway. He also enlarged the picture on the wall, which shows part of a Cupid in the style of Caesar van Everdingen, which we shall encounter in toto in other of Vermeer's paintings. There have been various attempts at emblematic interpretation of the scene, but unless we have a clear case of double meaning, such as we shall encounter in a few isolated instances, this type of interpretation has to be taken with a grain of salt.

The above underlines the difficulties inherent to the establishment of Vermeer's catalog. Not a single work can be traced back to the painter's studio, nor are there any letters or contracts extant. The task of attribution rests squarely upon the shoulders of the individual critic, which explains the multiplicity of divergent opinions. In this painting, a young woman stands in the center of the composition, facing in profile an open window to the left. In the foreground is a table covered with the same Oriental rug encountered in the Woman Asleep. On it is the identical Delft plate with fruit. The window reflects the girl's features, while to the right the large green curtain forms a deceptive frame. She is precisely silhouetted against a bare wall that reflects the light and envelops her in its luminosity.

We are here confronted with one of the salient aspects of Vermeer's sensibility and originality. It is the stillness that stands out, the inner absorption, the remoteness from the outer world. She concentrates entirely upon the letter, holding it firmly and tautly, while she absorbs its content with utmost attention.

In the technique, the artist avows again Rembrandtesque derivation. He paints in small fatty dabs to model the forms, and obtains the desired effects by means of impasto highlights opposed to the deeper tonalities - just as the master from Leyden was wont to do. The painting is relatively large, and the smallness of the figure as opposed to its surroundings stresses immateriality and depersonalization. Vermeer considerably changed the composition in the course of execution.

Much has been written about the trompe-l'oeil effect of the curtain. It is a pictorial artifice used by many other Dutch masters and in keeping with an old European tradition. Rembrandt, Gerard Dou, Nicolaes Maes, and many still-life and even landscape painters made use of such curtains as a means of simulating effects that now seem theatrical. The light background can be found in many paintings by Carel Fabritius, the Goldfinch from 1654 at the Mauritshuis in The Hague being the most famous example.

Although the painting represents in truth two houses and was initially described as one house only, there does not seem to be any doubt about the identification. It is a very simple and appealing painting, which conveys to the viewer a typical aspect of Dutch life as one encountered it in the period. The habitation ensconces and protects its dwellers, while the facades show the viewer nothing but the outside of their intimate existence. This essential simplicity is translated by the artist into a representation of a quiet street imbued with dignity.

Contemporaries like de Hooch and Jan Steen also painted bricks and mortar, but their treatment is close only in appearance. Vermeer, as usual, elevated his aim into regions of philosophy that surpassed the pedestrian attempts of others by his calm majesty and feeling for shared intimacy, of which he alone was capable. If superficially, Vermeer resembles his Delft colleagues, he easily surpasses them by the depth of his mastery of light and mood. The painting must be chronologically ranged rather early, because he was the initiator of the genre in this particular fashion.

An X-ray shows that the artist had initially planned to add a standing girl to the right of the open alleyway, but eliminated her subsequently so as not to disturb the stillness and equilibrium of the composition. There are numerous painted and watercolor copies after this composition.

While painting with a brush loaded with pigments and applying them in a granulous fashion by thick dabs, Vermeer ingeniously develops his mastery as a luminist. The young woman is bathed in light, which streams in through the half open window to the left, and reflects itself from the cream-colored background that is enhanced to the left by very thin glazes of slightly pinkish tonalities. Her face, exceptionally conveying expression - joy and laughter - appears framed in a kerchief and the collar of her dress. That part of the figure, especially, reveals itself as a symphony of luminosity, set off by the dark sleeves of the yellow jacket on which glittering highlights dance. In contrast, the soldier in the black hat and red jacket is placed close to the viewer, from whom he turns his back. He is hardly more than a silhouette, but rather overpowering, given the relative importance accorded his bodily appearance.

The nearest foreground - the soldier on his chair and the dark-green part of the table cover - are so strongly enhanced that the use of an optical instrument by Vermeer for the structuring of the composition seems indisputable. We have here the typical effect of the inverted telescope: the foreground standing out in the manner of stage scenery, while the figure of the girl recedes into space. On the back of the wall, we find for the first time a map. This element of decoration reappears frequently in the artist's subsequent works.

Although the genre of "kitchen pieces" belongs to a long tradition in the Netherlands, with Joachim Beuckelaer and Pieter Aertsen in the sixteenth century being its initiators, it lost favor in the subsequent century, with the exception of Delft, where it endured. Vermeer's realization, however, has nothing in common with his archaic forerunners. His vision is concentrated on a single sturdy figure, which he executes in a robust technique, in keeping with the image that he wants to project. The palette features a subdued color scheme: white, yellow, and blue. But the colors are far from frank or strident, and are rather toned down, in keeping with the worn work clothes of his model.

The still life in the foreground conveys domestic simplicity, and the light falling in from the left illuminates a bare white kitchen wall, against which the silhouette of the maid stands out. One gains from this deceptively simple scene an impression of inner strength, exclusive concentration on the task at hand, and complete absorption in it. The extensive use of pointillé in the still life lets us presume the use of the inverted telescope in an effort to set off this part of the painting against the main figure and alert the viewer to the contrast between the active humanity of the maid and her inanimate environment.

The leaden window to the left was entirely over painted at the time of the purchase by the museum and replaced by a curtain and a view upon a landscape through an open window. When the painting became part of the museum's collections, it was cleaned and the over paints removed, restoring the original composition. This was the time when genre painting flourished, and artists like Pieter de Hooch, Jan Steen, Frans van Mieris, and Gerard Ter Borch, to name only a few, placed their figures into a light-filled room or courtyard, showing them either socializing or preoccupied with domestic chores. Vermeer's works set the tone for representations of the upper bourgeoisie, a social level more refined than that depicted by his contemporaries. This type of setting required finer and smoother pictorial rendition than, for instance, the Milkmaid.

Consequently, Vermeer adapted his brushwork to the new needs, and more than equaled a Frans van Mieris, for instance, in the delicacy and finesse of the execution. It is proposed by some critics that Vermeer was the originator of the genre. It was he who influenced Pieter de Hooch, not the other way around, as was previously assumed. His elegance, sophistication, and majestic stillness assert the primacy of his conceptions over the more pedestrian de Hooch, who attained brief artistic heights only under Vermeer's impetus during his Delft sojourn in the late 1650's.

Like 'A Lady and Two Gentlemen', this seduction scene contains an open window which features the warning figure of Temperance.

A young woman wearing an elegant red dress is seated in the foreground turned toward the left and looking half-smilingly at the viewer. It is one of the rare instances when Vermeer animates one of his figures with a semblance of expression. She seems to be courted by a fine gentleman, bent over and encouraging the young lady to take a sip from the wine glass that she holds in her hand. Farther back, another gentleman sits behind a table featuring an exquisitely painted still life of a silver plate, fruit, and white pitcher. The second male figure sits in a pose reminiscent of the Girl Asleep, apparently befuddled by too much wine. A Man's Portrait in the background may be one of the family portraits mentioned in the inventory of Vermeer's widow in 1676, which was part of his stock as a dealer. As to the coat of arms prominently displayed in the window, it belonged to a former neighbor's family that used to live in a house next to the Vermeer's.

The painting has been over cleaned, the last time in 1900, and the sitting man in the background was over painted during the eighteenth century, as comes out of the descriptions of 1744 and 1776. The room where the artist placed the composition resembles others frequently used by him. Patterns, windows, and walls reappear with minor changes. In this respect, Vermeer did not show much originality. His mastery resides in the delicacy of the execution, the use of light, and the grouping of his figures.

Topographic views of cities had become a tradition by the time Vermeer painted his famous canvas. Hendrik Vroom was the author of two such works depicting Delft, but they are more archaic because they followed the traditional panoramic approach that we remember from the two cityscapes by Hercules Seghers at the Berlin museum. The latter artist was one of the first to make use of the inverted Galilean telescope to transcribe the preliminary prints and their proportions (more than twice as high as wide) into the more conventional format of his paintings.

Vermeer executed his View of Delft on the spot, but the optical instrument pointed toward the city and providing the artist with the aspect translated onto canvas, which we admire for its conciseness and special structure, was not the camera obscura but the inverted telescope. It is only the latter that condenses the panoramic view of a given sector, diminishes the figures of the foreground to a smaller than normal magnification, emphasizes the foreground as we see it in the picture, and by the same token makes the remainder of the composition recede into space. The image thus obtained provides us with optical effects that, without being unique in Dutch seventeenth-century painting, as often claimed, convey a cityscape that is united in the composition and enveloped atmospherically into glowing light.

We admire the town, but it is not a profile view of a township, but a painting, an idealized representation of Delft, with its main characteristics simplified and then cast into the framework of a harbor mirroring selected reflections in the water, and a rich, full sky with magnificent cloud formations looming over it. This is chronologically the last painting by Vermeer that was executed in rich, full pigmentation, with color accents put in with a fully loaded brush. The artist outdid himself in a rendition of his hometown, which stands as a truly great interpretation of nature.

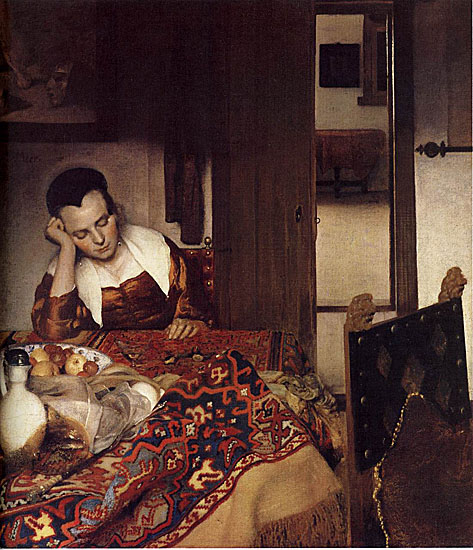

This seemingly trivial analysis as to what is being weighed actually bears importantly on the meaning of the work. For "Woman Holding a Balance" is overtly allegorical. The woman stands between a depiction of the Last Judgment hung in a heavy black frame and a table covered with jewelry representing material possessions. The empty scale stresses that she is balancing spiritual rather than material considerations. Vermeer's portrayal does not impart a sense of tension or conflict, rather the woman exudes serenity. Her self-knowledge is reflected in the mirror on the wall. Vermeer's point is that we should lead lives of moderation with full understanding of the implications of a final judgment.

The composition is designed to focus attention on the small and delicate balance being held. The woman's arms act as a frame, with the small finger of her right hand extended to echo the horizontal lever of the balance. The bottom of the painting frame is even altered to provide a partial niche for the scales. The frame ends higher in front of the woman than it does behind her. The complex interplay between verticals and horizontals objects and negative space and light and shadow results in a strongly balanced, yet still active composition. The scales are balanced, but dynamically asymmetrical. A cleaning in 1994 revealed previously undetectable gold trim on the black frame that provides a tonal link to the yellow of the curtain and the woman's costume.

Vermeer has endowed "Woman Holding a Balance" with more overtly allegorical context than his other domestic scenes. As such, it loses some of the invitingly subjective interpretation of a less direct work such as "Woman in Blue Reading a Letter". Nevertheless, Vermeer's masterful composition and execution produced a powerful and moving work.

The perfect balance of the composition, the cool clarity of the light, and the silvery tones of blue and gray combine to make this closely studied view of an interior a classic work by Vermeer. It is characteristic of his early maturity and dates from the beginning of the 1660's.

The composition is simple: a young woman standing in the corner of a room, turned to the left, opening a window with her right hand and holding in her left hand a brass water jug. The jug is placed on a bowl of the same material, standing with some other paraphernalia on a table covered with a red Oriental rug. The whole appears as a symphony in yellow and blue; standing out against the white headdress and large collar worn by the young woman. The background is light, in imitation of Carel Fabritius. A map animates the right corner of the wall. The very simplicity and Oriental stillness of the model make this work one of the most significant compositions by the master. There is light, grace, and distinction here, a tendency toward abstraction that characterizes the master's maturity, and a delicacy in the execution that accompanies his evolution from: the early works toward a more artful manner of pictorial expression.

The girl is seen against a neutral, dark background, very nearly black, which establishes a powerful three-dimensionality of effect. Seen from the side, the girl is turning to gaze at us, and her lips are slightly parted, as if she were about to speak to us. It is an illusionist approach often adopted in Dutch art. She is inclining her head slightly to one side as if lost in thought, yet her gaze is keen.

The girl is dressed in an unadorned, brownish-yellow jacket, and the shining white collar contrasts clearly against it. The blue turban represents a further contrast, while a lemon-yellow, veil-like cloth falls from its peak to her shoulders. Vermeer used plain, pure colors in this painting, limiting the range of tones. As a result, the number of sections of color are small, and these are given depth and shadow by the use of varnish of the same color.

The girl's headdress has an exotic effect. Turbans were a popular fashionable accessory in Europe as early as the 15th century, as is shown by Jan van Eyck's probable self portrait, now in the National Gallery in London. During the wars against the Turks, the remote way of life and foreign dress of the "enemy of Christendom" proved to be very fascinating. A particularly noticeable feature of Vermeer's painting is the large, tear-shaped pearl hanging from the girl's ear; part of it has a golden sheen, and it stands out from the part of the neck which is in shadow.

In his Introduction to the Devout Life (1608), which was published in a Dutch translation in 1616, the mystic Saint Francis De Sales (1567-1622) wrote, "Both now and in the past it has been customary for women to hang pearls from their ears; as Pliny observed, they gain pleasure from the sensation of the swinging pearls touching them. But I know that God's friend, Isaac, sent earrings to chaste Rebecca as a first token of his love. This leads me to think that this jewel has a spiritual meaning, namely that the first part of the body that a man wants, and which a woman must loyally protect, is the ear; no word or sound should enter it other than the sweet sound of chaste words, which are the oriental pearls of the gospel."

From this it is clear that the pearl in Vermeer's painting is a symbol of chastity. The oriental aspect, which is mentioned in the above extract, is further emphasized by the turban. The reference to Isaac and Rebecca suggests that this picture could have been painted on the occasion of this young woman's marriage. So to that extent it is a portrait.

There is surely a similar explanation for the Head of a Girl dressed in a smart, grey dress (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). One must admire the artist's technique, which features application of the pigments in juxtaposition and melting, avoiding precise lines, and therefore blurring the contours of different colors so as to obtain effects that foreshadow those of the impressionists. The dark backgrounds that Vermeer chose in these two portraits enhance the plasticity of the models.

This painting superficially resembles 'A Lady at the Virginals with a Gentleman' (Buckingham Palace, London) in that it features the making of music in a domestic environment. But there the similarity stops. 'The Lady at the Virginals' was very rigidly constructed, pruned to the point of abstraction, and allowing the viewer only a glance from afar upon the principal scene. In the Concert, we are again part of the happening, although separated from it by the table covered with the familiar red Oriental rug and the bass viol on the floor.

However, the music-making trio in a compact group presents itself sufficiently close to our vision so that the viewer shares in the earnest concentration of the figures. This slightly removed part of the painting is particularly rich in details, almost pictures within the picture. On the far wall to the right, we find Baburen's Procuress, which was part of Vermeer's stock as an art dealer. To the left is a landscape in the style of Jacob van Ruisdael. The two are linked by the landscape on the raised cover of the clavecin done in the then-fashionable style of the Italianizing Dutch landscape painters such as Jan Both.

For Vermeer, such a crowding of decorative elements is rather unusual, and has therefore encouraged critics to attempt various interpretations of the meaning of the scene. They range from calling it a brothel (de Mirimonde) to a domestic scene with the lady to the right being the personification of temperance (I. L. Moreno)! In any case, the amateur seeking purely aesthetic pleasure will find delight in the perfection of the composition, the delicate execution of the figures, as well as of the paraphernalia, and the masterly use of diffused light enveloping the actors. In this work, Vermeer stands greatly above his contemporaries de Hooch, Jan Steen, Metsu, and many others, in harmony, grandeur, and artistic skill.

Interestingly, this painting was certainly the prototype that inspired the 'Girl with a Red Hat' in the National Gallery of Art, Washington (According to some critics this painting is not by Vermeer but a later pasticcio.)

This painting of Vermeer does not enjoy as much favor as the "Gioconda of the North," although it is, in many respects, a much better picture.

This painting was long called 'The Artist in His Studio', and we may in effect presume that the artist seen from behind was himself. However, the intention of representing an allegory is stronger here than in all other Vermeer's works. The heavy curtain on the left, which lets the viewer partake of the scene, has decidedly theatrical connotations. So does the young girl whom the artist portrays, and whose crown of laurel easily identifies her as Fame. A connection with Clio, the muse of history, also exists. She holds a trumpet and a book of Thucydides.

The whole composition is a panegyric to the art of painting. Set in an elegant room, with a chandelier, chairs, the lush curtain, and a large map on the back wall, which shows the northern and southern Netherlands and indicates the area over which the reputation of the artist could spread, its overall meaning emphasizes the attainment of fame to the benefit of the man in the pursuit of his artistic endeavors as well as 'qua' citizen of his hometown.

The uncommonly large painting, considered from the pictorial viewpoint only, is rather decorative but lacks depth. Only its meaning makes it of particular interest. Repeated restorations may have contributed to the narrative rather than painterly excellence of the work. Such as it presents itself now, one cannot be astonished that it was formerly attributed to Pieter de Hooch.

The mistress, sitting at a table and turned to the left, wears the same yellow jacket with an ermine border as the 'Lady Writing a Letter'. The maid interrupts her writing and hands her a letter. Both figures are close to the foreground, strongly illuminated, and standing out against the dark background, which lacks further adornment and remains undefined. For Vermeer, this is an unusually large composition, which focuses on a moment of interaction and interruption, rather than on a contemplation of stillness and introvert thoughtfulness. This new approach enhances the monumentality of the scene.

It is assumed by some critics that this painting is not by Vermeer, but one of the French fakes produced at the beginning of the nineteenth century. In this case it originates from the same faker's studio as the 'Girl with a Red Hat' (National Gallery of Art, Washington).

In this painting Vermeer repeated the posture of the arm in The Girl with a Flute, though she is seen from the other side, and is therefore leaning on her right arm, against the backrest of a chair decorated with lions' heads and rings. This picture was quite evidently painted with the aid of a camera obscura. That is indicated by his use of pointillism, bright dots of paint and occasional highlights on the folds. The light is falling at an angle from above onto her soft, feathery hat; on the top it is vermilion, and the lower shadowed part is a dark purple color. The intensity of the light is such that the hat appears, at points, to be transparent. Its broad brim has the effect of casting a shadow over most of her face; only her left cheek, below her eye, is lit. The shading of her eyes, the centre of her face, is quite intentional; the principle of dissimulatio, a mysterious disguise, is being applied here, the intended effect being to heighten our curiosity.

It is assumed by some critics that this painting is not by Vermeer, but a later pasticcio. It and the 'Girl with a Flute' (in the same museum) are painted on wood, whereas all authentic Vermeer paintings are done on canvas. This work has been painted on an upside-down Rembrandtesque portrait of a man, and pigments considered to be older than the nineteenth century found in this painting come from the original and not from the modern pasticcio.

Until 1778, they remained together. The signatures and dates on both paintings are questionable, but they must have been executed toward the end of the 1660's.

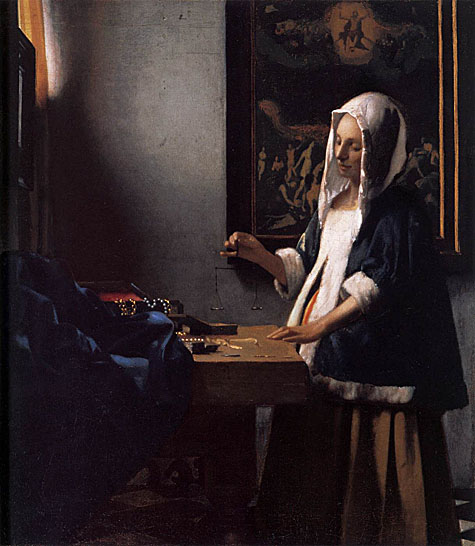

None of these paintings appears in the sale of 1696, and were therefore commissioned by a patron who was especially interested in astronomy or the celestial sciences. In both paintings, the references to books, scientific instruments, and, in the portrait of the Astronomer, the celestial globe by Jodocus Hondius, are accurately depicted.

The latter painting features on the rear wall a picture representing the scene of the finding of Moses, which has been interpreted as being associated with the advice of divine providence in reaching, in the case of the astronomer, for spiritual guidance.

Although farfetched, it is likely that the content of the painting is associated in some way with the meaning of the work. The sea chart on the wall of the Geographer does not have any religious association. It must be remembered that the rise of interest in scientific research at the time, fostered by the newly established University of Leyden, and philosophers like Descartes, did not have any specific religious associations. Quite to the contrary, the aim was to explore the universe, and simultaneously to further Dutch navigation in its conquest of faraway lands.

Both paintings, with their interiors of scholarly studios and scientific paraphernalia, award Vermeer the opportunity for lightening effects that envelop the scientists in the mystery of an atmosphere that lifts their occupations into the realm of spirituality.

None of these paintings appears in the sale of 1696, and were therefore commissioned by a patron who was especially interested in astronomy or the celestial sciences. In both paintings, the references to books, scientific instruments, and, in the portrait of the Astronomer, the celestial globe by Jodocus Hondius, are accurately depicted.

The latter painting features on the rear wall a picture representing the scene of the finding of Moses, which has been interpreted as being associated with the advice of divine providence in reaching, in the case of the astronomer, for spiritual guidance.

Although farfetched, it is likely that the content of the painting is associated in some way with the meaning of the work. The sea chart on the wall of the Geographer does not have any religious association. It must be remembered that the rise of interest in scientific research at the time, fostered by the newly established University of Leyden, and philosophers like Descartes, did not have any specific religious associations. Quite to the contrary, the aim was to explore the universe, and simultaneously to further Dutch navigation in its conquest of faraway lands.

Both paintings, with their interiors of scholarly studios and scientific paraphernalia, award Vermeer the opportunity for lightening effects that envelop the scientists in the mystery of an atmosphere that lifts their occupations into the realm of spirituality.

The painting accurately renders the cartographic objects that express the theme: the sea chart, globe, dividers, square and a cross-staff that was used to measure the elevation angle of the sun and stars. It is probable that Vermeer's sophisticated presentation of these instruments was informed by his association with famed scientist Anthony Van Leeuwenhoek. Although no documents exist linking the two, they were both born in Delft in the same year. A contemporary portrait of Leeuwenhoek closely resembles the figure in Vermeer's geographer, and it is very possible that Leewenhoek served as the model.

Another Vermeer work, "The Astronomer", is commonly considered a pendant to "The Geographer". In it, the same model is depicted, this time among the instruments of astronomical study. Both paintings dramatically convey the excitement of scholarly inquiry and discovery. Considering these works as pendants offers an allegorical interpretation: the astronomer, student of the heavens, searches for spiritual guidance; the geographer, student of the earth, charts the proper course for temporal life.

The intimacy is accentuated by the small scale, personal subject matter, and natural composition. The Lacemaker's total preoccupation with her work is indicated through her confined pose. The use of yellow, a dynamic, psychologically strong hue, reinforces the perception of intense effort. Contrasts of form serve to animate the image. For example, her hairstyle expresses her essential nature - both tightly constrained and, in the loose ringlet behind her left shoulder, rhythmically flowing. Another strong contrast exists between the tightly drawn threads she holds and the smoothly flowing red and white threads in the foreground. The precision and clearness of vision demanded by her work is expressed in the light accents that illuminate her forehead and fingers.

The diffused ocular effect of the foreground objects, especially the threads, was definitely derived from a camera obscura image. Vermeer used the informal, close framing of the composition suggested by the camera obscura to accentuate the realistic, immediate impact of the painting. Contemporary Dutch painting portrayed industriousness as an allegory of domestic virtue, while the inclusion of the prayer book pays fealty to this theme, it is a secondary concern to the depiction of the handicraft of lacemaking, and, in the highest sense, the creative act itself. Once again, Vermeer succeeded in transforming a transitory image into one of eternal truth.

The identical map recurs distinctly rendered in the Officer with a 'Laughing Girl' (Frick Collection, New York). The other objects nearest the viewer are also muted and almost blurred. On the other hand, the mistress and her maid, as well as the room in which they are placed, are well defined in spite of their recession into space.

The composition is attractive and treated in a decorative manner, although the two figures are devoid of individualization and resemble puppets rather than persons. Part of this shallowness may be due to damage from the theft and subsequent holding for ransom of the painting, which occurred at an exhibition in Brussels in 1971. The picture suffered much more than was later admitted, and no restorer, however skilful, can equal Vermeer.

The canvas presents a deceptively simple composition. The placid scene with its muted colors suggests no activity or hint of interruption. Powerful verticals and horizontals in the composition, particularly the heavy black frame of the background painting, establish a confining backdrop that contributes to the restrained mood.

The composition is activated by the strong contrast between the two figures. The firm stance of the statuesque maid acts as a counterweight to the lively mistress intent on writing her letter. The maid's gravity is emphasized by her central position in the composition. The left upright of the picture frame anchors her in place while the regular folds of her clothing sustain the effect down to the floor. In contrast, the mistress inclines dynamically on her left forearm. Her compositional placement thrusts her against the compressed space on the right side of the canvas. Strong light outlines the writing arm against the shaded wall, reflecting in angular planes from the blouse that contrast abruptly with the regimented folds of the maid's costume. The mistress is painted in precise, meticulous strokes as opposed to the broad handling of the brush used to depict the maid.

The figures although distinct individuals are joined by perspective. Lines from the upper and lower window frames proceed across the folded arms and lighted forehead of the maid, extending to a vanishing point in the left eye of the mistress. The viewer's eye is lead first to the maid, then on to the mistress as the focal point of the painting.

Vermeer shuns direct narrative content, instead furnishing hints and allusions in order to avoid an anecdotal presentation. The crumpled letter on the floor in the right foreground is a clue to the missive the mistress is composing. The red wax seal, rediscovered only recently during a 1974 cleaning, indicates the crumpled letter was received, rather than being a discarded draft of the letter now being composed. Since letters were prized in the 17th century, it must have been thrown aside in anger. This explains the vehement energy being devoted to the composition of the response. Another hint is provided in the large background painting, "The Finding of Moses".

Contemporary interpretation of this story equated it with God's ability to conciliate opposing factions. These allusions have led critics to construe Vermeer's theme as the need to achieve reconciliation, through individual effort and with faith in God's divine plan. This spiritual reconciliation will lead to the serenity personified in the figure of the maid.

The subject matter for this allegory obviously did not suit Vermeer's taste. In the 'Art of Painting' (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), he produced, in spite of the intrusion of iconographic material, a composition that conveyed a psychological approach joined to artistic execution. Even so, it was not really as successful as other works that imply thoughtfulness or meditation.

'The Allegory of Faith' is fraught with details that evidently were prescribed by the spiritual fathers (probably the Jesuits, although the first known owner of the painting was a Protestant) of the composition, but that did not fit into an artistic image with which Vermeer could cope.

Hence, we have here an exercise in classicism, of abstract concepts, which led to a mediocre result. The artist's creativity had, in any case, declined by then into a brittle style with no more inner warmth or ability to communicate.

Thus, we are in the presence of a rather dry amalgamate, drawn in the main from Cesare Ripa's book Iconologia, to which a large Crucifixion by Jacob Jordaens on the back wall is added as a backdrop. Hence, this allegorical representation of the "New Testament" can have served as a didactic introduction to some aspects of the Catholic faith.

Together with the 'Lacemaker' (Louvre, Paris), this painting constitutes one of the best achievements by Vermeer, and certainly a towering success in his late maturity. By now, the artist had attained the mastery of light and colors, together with complete freedom of expressing himself technically by means of looser brushstrokes that are no longer bound to specifics of texture or materials. The model is not drawn inward but looks to the outside world in full communication and radiance of her pleasure simply to make music. Never was Vermeer more able to liberate himself from all constraints and convey his artistic viewpoint in a more masterly manner. The landscape on the back wall seems to be painted in the style of Hackaert.

The painting represents a musical theme familiar from several of Vermeer's larger paintings, in particular the two in the National Gallery, London. It shows a young woman, three-quarters length, seated on a chair of rich blue velvet, her hands extended towards the keyboard of the virginals, a variant of the same instrument shown in one of the National Gallery's paintings. She is dressed in a yellow woolen shawl above a white satin dress or skirt, with pearls around her neck and an arrangement of red and white ribbons in her hair. As in Vermeer's other small canvases, the figure and instrument are set against a plain wall, without any other compositional elements such as windows, curtains or background paintings; yet despite this, the artist has created a highly convincing and atmospheric impression of space and depth, thanks to the depiction of minute irregularities and holes in the plaster of the wall, and the presence of a delicate, unified light, which comes, as in most of Vermeer's interiors, from the top left of the composition.

Whereas the 'Lady Standing at the Virginal' (National Gallery, London) is bathed in light, this putative companion piece features a subdued atmosphere. The shade is drawn here, and though we can make out every detail in the limpid light, Baburen's 'Procuress' hanging on the back wall furnishes the main contrast. It is curious to observe that while inanimate objects - the clavecin, the bass viol in the foreground to the left, and the decorations of the musical instrument - are extremely detailed, the curtain to the left is stiff, and the lady making music is devoid of expression, depersonalized, and faultily drawn (see, e.g., her arms).

There can be no question that the paintings from these last years are vastly inferior to what we have been accustomed to by Vermeer.

As we might suspect in an artist with his aspirations, Vermeer injected narrative or allegorical significance even into his domestic interiors. The young woman strokes the keys of the virginal - a smaller version of the harpsichord - but looks expectantly out of the picture. Music, we recall, is the 'food of love', and the empty chair calls to mind an absent sitter, perhaps travelling abroad among the mountains depicted in the picture on the wall and on the lid of the virginal. Cupid holding up a playing card or tablet has been related to an emblem of fidelity to one lover, as illustrated in one of the popular contemporary Dutch emblem books, where the image is explained in the accompanying motto and text. It has been suggested, not altogether convincingly, that the painting forms a contrasting pair with its neighbor, Vermeer's 'Young Woman seated at a Virginal', where the viola da gamba in the foreground awaits the partner of a duet but the picture of the Procuress (by the Utrecht artist Baburen) behind the woman points to mercenary love.

Whether or not the paintings are thus related, both surely portray young women dreaming of love. But the theme seems commonplace beside Vermeer's treatment of it. Cool daylight streams in through the window on the left, as it always does in his pictures. The textures of grey-veined marble and white-and-blue Delft tiles, of gilt frame and whitewashed wall, of blue velvet and taffeta and white satin, of scarlet bows, are differentiated through the action of this light in their most minute particularities and specific luster. Volume is revealed, shadows cast and space created. Yet the real magic of the painting is that all this does not, as it were, exhaust the light. Enough of it remains as a palpable presence diffused throughout the room to reach out to us beyond the picture's frame.

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.