Netherlands Northern Renaissance Artist

1395 - 1441

Jan van Eyck or Johannes de Eyck was an Early Netherlands painter active in Bruges and considered one of the best Northern European painters of the 15th century.

There is a common misconception, which dates back to the sixteenth-century Vita of the Tuscan artist and biographer Giorgio Vasari, that Jan van Eyck invented oil painting. It is however true that he achieved, or perfected, new and remarkable effects using this technique.

Jan van Eyck has often been linked as brother to painter and peer Hubert van Eyck, because both have been thought to originate from the same town, Maaseik in Limburg (Belgium). Another brother, Lambert van Eyck is mentioned in Burgundian court documents, and there is a conjecture that he too was a painter, and that he may have overseen the closing of Jan van Eyck's Bruges workshop. Another significant, and rather younger, painter who worked in Southern France, Barthélemy van Eyck, is presumed to be a relation.

The date of van Eyck's birth is not known. The first extant record of van Eyck is from the Court of John of Bavaria at The Hague, where payments were made to Jan van Eyck between 1422 and 1424 as court painter, with the court rank of valet de chambre, and first one and then two assistants. This suggests a date of birth after 1395, and indeed probably earlier. His apparent age in his probable self-portrait (below) suggests to most scholars an earlier date than 1395. Miniatures in the Turin-Milan Hours, if indeed they are by van Eyck, are likely to be the only surviving works from this period, and about half of these were destroyed by fire in 1904.

Van Eyck's ability to depict it in such a realistic manner relies greatly on his control of the oil medium, which unlike tempera enables him to represent dark shadows and paler highlights without losing the glowing overall red hue.

Following the death of John of Bavaria, in 1425 van Eyck entered the service of the powerful and influential Valois prince, Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy. Van Eyck resided in Lille for a year and then moved to Bruges, where he lived until his death in 1441. A number of documents published in the twentieth century record his activities in Philip's service. He was sent on several missions on behalf of the Duke, and worked on several projects which likely entailed more than painting. With the exception of two portraits of Isabella of Portugal, which van Eyck painted on Philip's behest as a member of a 1428-29 delegation to seek her hand, the precise nature of these works is obscure.

As a painter and "valet de chambre" to the Duke, Jan van Eyck was exceptionally well paid. His annual salary was quite high when he was first engaged, but it doubled twice in the first few years, and was often supplemented by special bonuses. His salary alone makes Jan van Eyck an exceptional figure among early Netherlands painters, since most of them depended on individual commissions for their livelihoods. An indication that Van Eyck's art and person were held in extraordinarily high regard is a document from 1435 in which the Duke scolded his treasurers for not paying the painter his salary, arguing that Van Eyck would leave and that he would nowhere be able to find his equal in his "art and science." The Duke also served as godfather to one of Van Eyck's children, supported his widow upon the painter's death, and years later helped one of his daughters with the funds required to enter a convent.

Jan van Eyck produced paintings for private clients in addition to his work at the court. Foremost among these is the Ghent Altarpiece painted for Jodocus Vijdts and his wife Elisabeth Borluut. Started sometime before 1426 and completed, at least partially, by 1432, this polyptych has been seen to represent "the final conquest of reality in the North", differing from the great works of the Early Renaissance in Italy by virtue of its willingness to forgo classical idealization in favor of the faithful observation of nature. It is housed in its original location, the Cathedral of Saint Bavo in Ghent, Belgium. It has had a turbulent history, surviving the 16th-century iconoclastic riots, the French Revolution, changing tastes which led to its dissemination, and most recently Nazi looting. When World War II ended it was recovered in a salt mine, and the story of its restoration drew considerable interest from the general public and greatly advanced the discipline of the scientific study of paintings. No less turbulent was the history of the interpretation of this work. Since an inscription states that Hubert van Eyck maior quo nemo repertus (greater than anyone) started the altarpiece, but that Jan van Eyck - calling himself arte secundus (second best in the art) - finished it identifies it as a collaborative effort of Jan van Eyck and his brother Hubert. The question of who painted what, or "Jan or Hubert?" has become a mythical one among art historians. Some even question the validity of the inscription, and thus Hubert van Eyck's involvement. In the 1930's, Emil Renders even argued that "Hubert van Eyck" was a complete fiction invented by Ghent humanists in the 16th century. More recently, Lotte Brand Philip (1971) has proposed that the Ghent Altarpiece's inscription has been misread, and that Hubert was (in Latin) the "fictor", not the "pictor", of the work. She interprets this as meaning that Jan van Eyck painted the entire altarpiece, while his brother Hubert created its sculptural framework.

_1432.jpg)

An additional argument for the existence of Hubert is provided by a stylistic analysis of the painting, in which the work of two different hands can be clearly discerned. The overall conception of the altarpiece is certainly the work of Hubert, along with the execution of certain parts, such as the panels in the lower tier. Here, the manner is archaic, and reflects the continuing dominance of the international style that was practiced by Broederlam. The composition is typically unoriginal: the landscape is still conceived as a distant background, with which the figures at the front have no organic relation, an effect that is reinforced by the bird's eye point of view.

This polyptych is mystical, not to say esoteric, in intention, and is imbued throughout with both spiritual and intellectual signification. When opened, it represents the communion of saints, which is "the new heaven and the new earth", in the words of the Revelation of St John. Thus the central panel of the lower tier portrays the saints symbolizing the eight Beatitudes gathered round the altar where the sacrifice of the Lamb is taking place, at the centre of the heavenly garden which has sprung from His blood.

To left and right in the foreground are two processions facing one another. One of these is made up of the Old Testament patriarchs and prophets, and the other of figures from the New Testament. Some of them are kneeling, barefoot. Behind them is assembled the hierarchy of the Church - popes, deacons and bishops, wearing sumptuous jewelry and clothes in the bright red of martyrdom. In the background are two further groups, facing each other as if they had just emerged from the surrounding shrubbery. These are, on one side, the Confessors of the Faith, tightly packed together and almost all dressed in blue; and on the other side, the Virgin Martyrs, holding out palm fronds and wearing in their hair crowns of flowers of a kind traditionally worn by young girls at certain holy ceremonies. In the middle of the panel, around the altar where the Lamb spills forth his blood, angels kneel, holding the emblems of His Passion. Grace is symbolized by a radiant dove hovering in the sky, and eternal life is represented by a fountain in the foreground. A paradisiacal landscape runs across all five lower panels, uniting them in a single composition. It is strewn with plants from different countries and flowers of different seasons. The central panel is vibrant with green, while those to the sides are more arid and rocky. The horizon sits high in the frame and is closed off by groves of trees, behind which clusters of fairy-tale buildings can be made out, representing the heavenly Jerusalem.

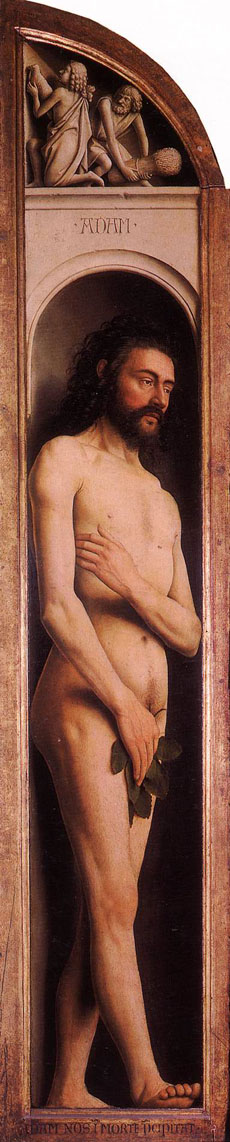

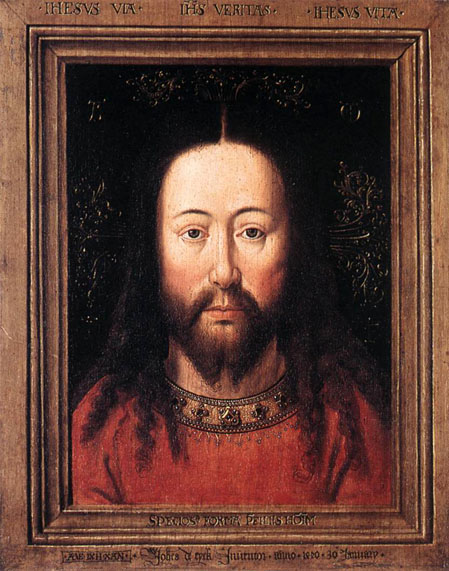

The community of saints also extends onto the side panels. Magnificently arrayed horsemen, representing the Soldiers of Christ, are followed by the Just Judges. Opposite them are the Holy Hermits who have renounced the world, and the Pilgrim Saints, who were favorite figures of identification throughout the Middle Ages. They are led by a giant of a man, Saint Christopher. Many later commentators have suggested that his great height would have reminded the contemporary viewer of Jodocus Vijd's brother, also called Christopher. In the middle of the upper tier is God Almighty, the Word, essence and origin of the universe. He is dressed in red and is crowned with a magnificent tiara. On his left is Mary and on his right, St John the Baptist. These central figures are surrounded by angels who are singing or playing instruments. At the far right and left of the composition respectively are the figures of Adam and Eve. They were painted by Jan Van Eyck, and are set into trompe-l'oeil niches. Light and shadow play delicately over their forms which stand out as though they had been sculpted in the round.

_1425_29.jpg)

_1426_29.jpg)

_1426_27.jpg)

_1425_29.jpg)

Connected with the trio of God the Father, surrounded by the Virgin Mary and Saint John the Baptist, these wingless angels belong to the "heavenly domain", and they not only sing the praises of the Lord but also invoke the music of the spheres. At the same time, their presence is connected to the events depicted in the lower part of the panels: the use of identical sky background proves this.

_1427_29.jpg)

Gaudentia: joy on account of the Lord's greatness (Magnificus)

Spes: hope for the Lord's generosity (Largus)

Pietàs: devout love toward the Lord's graciousness (Pius)

Timor: fear of the Lord's justness (Iustus)

Dolor: grief, sadness, and repentance before the Lord's mercifulness (Miserator)

_Two_1427_29.jpg)

_Three_1427_29.jpg)

To left and right, in the foreground, are two processions facing one another. One of these is made up of the Old Testament patriarchs and prophets, and the other of figures from the New Testament. Some of them are kneeling, barefoot. Behind them is assembled the hierarchy of the Church - popes, deacons and bishops, wearing sumptuous jewelry and clothes in the bright red of martyrdom.

In the background are two further groups, facing each other as if they had just emerged from the surrounding shrubbery. These are, on one side, the Confessors of the Faith, tightly packed together and almost all dressed in blue; and on the other side, the Virgin Martyrs, holding out palm fronds and wearing in their hair crowns of flowers of a kind traditionally worn by young girls at certain holy ceremonies.

In the middle of the panel, around the altar where the Lamb spills forth his blood, angels kneel, holding the emblems of His Passion. Grace is symbolized by a radiant dove hovering in the sky, and eternal life is represented by a fountain in the foreground. A paradisiacal landscape runs across all five lower panels, uniting them in a single composition. It is strewn with plants from different countries and flowers of different seasons. The central panel is vibrant with green, while those to the sides are more arid and rocky. The horizon sits high in the frame and is closed off by groves of trees, behind which clusters of fairy-tale buildings can be made out, representing the heavenly Jerusalem.

_1425_29.jpg)

_Two_1425_29.jpg)

_Three_1425_29.jpg)

_Four_1425_29.jpg)

_Five_1425_29.jpg)

_Six_1425_29.jpg)

_1432.jpg)

A striking feature is the disparity in the scale of the various figures: no less than four changes of scale exist of the outside of the wings. There are also disparities in approach; some parts are almost prosaically factual, others almost visionary in approach. Three orders of reality are present: a narrative representation of a sacred subject (the Annunciation), two highly factual donor portraits and two simulated sculptures. Yet there is a strong attempt to impose a uniform framework on these disparate elements through the governing factor of the light, which falls uniformly in all the panels from the right, and also through the use in the upper panels of a beamed ceiling running through the whole scene, and, in the lower panels, of the same cusped trefoil arches to frame the figures.

Jodocus Vyd, deputy burgomaster of Ghent, warden of the church of Saint John, was one of the richest businessmen of his age in Flanders.

_1432.jpg)

_1432.jpg)

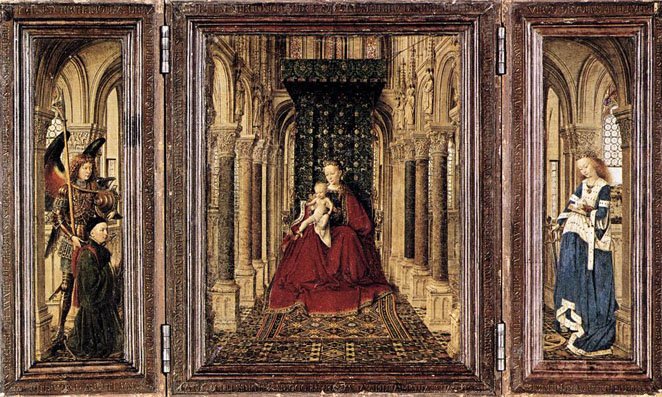

Exceptionally for his time, van Eyck often signed and dated his paintings on their frames, then considered an integral part of the work (the two were often painted together). However, in the celebrated Arnolfini Portrait (London, National Gallery), van Eyck inscribed on the (pictorial) back wall above the convex mirror "Johannes de Eyck fuit hic 1434" (Jan van Eyck was here, 1434). The painting is one of the most frequently analyzed by art historians, but in recent years a number of popular interpretations have been questioned. This is probably not a painted marriage certificate, or the record of a betrothal, as originally suggested by Erwin Panofsky. The woman is probably also not pregnant, as the hand-gesture of lifting the dress recurs in contemporary renditions of virgin saints (including Jan van Eyck's own Dresden Triptych and a workshop piece, the Frick Madonna).

Giovanni Arnolfini, a prosperous Italian banker who had settled in Bruges, and his wife Giovanna Cenami, stand side by side in the bridal chamber, facing towards the viewer. The husband is holding out his wife's hand.

Despite the restricted space, the painter has contrived to surround them with a host of symbols. To the left, the oranges placed on the low table and the windowsill are a reminder of an original innocence, of an age before sin. Unless, that is, they are not in fact oranges but apples (it is difficult to be certain), in which case they would represent the temptation of knowledge and the Fall. Above the couple's heads, the candle that has been left burning in broad daylight on one of the branches of an ornate copper chandelier can be interpreted as the nuptial flame, or as the eye of God. The small dog in the foreground is an emblem of fidelity and love. Meanwhile, the marriage bed with its bright red curtains evokes the physical act of love which, according to Christian doctrine, is an essential part of the perfect union of man and wife.

Although all these different elements are highly charged with meaning, they are of secondary importance compared to the mirror, the focal point of the whole composition. It has often been noted that two tiny figures can be seen reflected in it, their image captured as they cross the threshold of the room. They are the painter himself and a young man, doubtless arriving to act as witnesses to the marriage. The essential point, however, is the fact that the convex mirror is able to absorb and reflect in a single image both the floor and the ceiling of the room, as well as the sky and the garden outside, both of which are otherwise barely visible through the side window. The mirror thus acts as a sort of hole in the texture of space. It sucks the entire visual world into itself, transforming it into a representation.

The cubic space in which the Arnolfinis stand is itself a pre-figuration of the techniques of perspective which were still to come. Van Eyck practiced perspective on a purely heuristic basis, unaware of the laws by which it was governed. In this picture, he uses the mirror precisely in order to explode the limits of the space to which his technique gives him access as soon as it threatens to limit him.

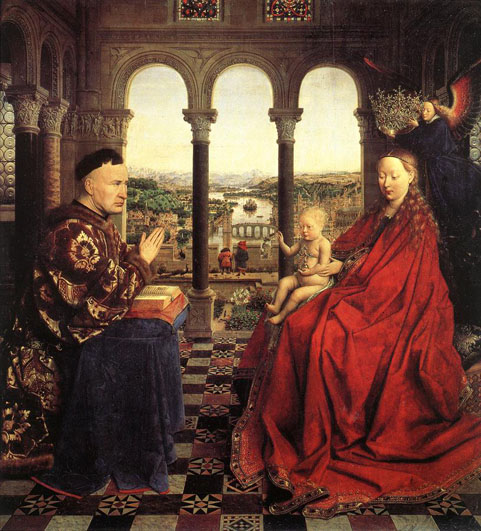

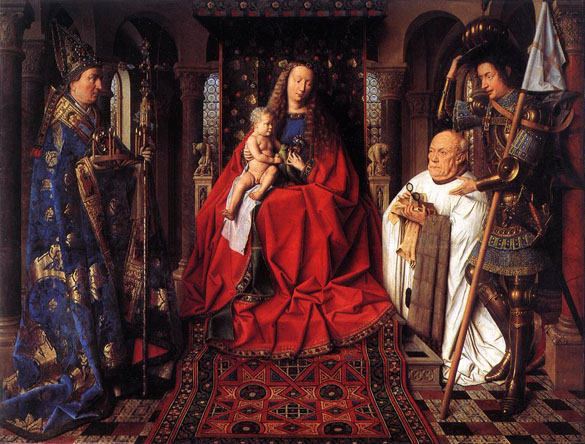

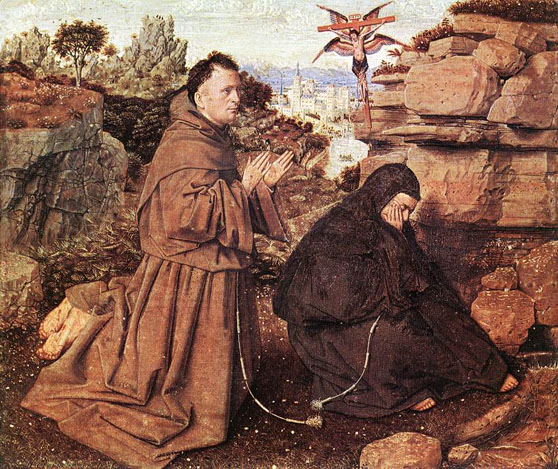

Other works include two remarkable commemorative panels, the Madonna with Chancellor Rolin (Paris, Louvre), and the Madonna of Canon Georg van der Paele (Bruges, Groeninge Museum), some other religious paintings, notably the Annunciation (Washington, National Gallery of Art), and a number of exceptionally haunting portraits, including that of his wife, Margareta (Bruges, Groeningemuseum), and what is believed to be his self-portrait,Portrait of a Man (Self Portrait?), often mis-titled Portrait of a Man in a Red Turban, as in fact he wears a chaperon. Many more works are disputed, or believed to be by his assistants or followers.

Nicolas Rolin, who commissioned this work, was a man with a forceful personality. Despite his humble background, he was highly intelligent and eventually rose to hold the highest offices of State. For over forty years he was Philip the Good's right-hand man, and one of the principal architects of the monarch's success. Van Eyck painted him when he was already in his sixties. His face, though marked by the heavy responsibilities he has had to bear, still fascinates the viewer with the sense of energy and will-power which it projects. Rolin is wearing a gold brocade jacket trimmed with mink. He kneels at prayer on the left of the composition. His gaze is pensive, looking as though he has just raised his eyes from his book of hours.

On the right is the seated figure of the Virgin. Wrapped in a voluminous red robe, she is presenting the Infant Jesus to the chancellor while a hovering angel holds a magnificent crown above her head. The figures have been brought together in the loggia of an Italianate palace. The three arches through which the space opens out behind them seem rather large in relation to their immediate surroundings. They give first onto a small garden with lilies and roses symbolizing Mary's virtues. Slightly farther back are two small figures, one standing at an oblique angle to the viewer and the other with his back to us. Near them are two peacocks, symbols of immortality, but perhaps also of the pride to which such a powerful man as Chancellor Rolin might well succumb.

The most surprising feature in this splendid picture is without doubt the townscape that stretches out beyond the loggia. The crenellated battlements indicate that the palace is in fact a fortress, built on the edge of an escarpment. Below, a broad meandering river with an island in its midst flows through the heart of a city. The humbler areas of the town lie to the left, behind Chancellor Rolin. On the right, behind the Virgin, are the wealthy quarters, with a profusion of buildings, dominated by an imposing Gothic church. Countless tiny figures are flocking towards this part of town, across the bridge and through the roads and squares. Meanwhile on the river, boats are arriving and putting into shore. It is as if all mankind, united by faith, were travelling in pilgrimage towards this city and its cathedral. In the distance, the horizon is closed off by snow-capped mountains under a pinky-yellow sky. In the opinion of Charles de Tolnay, this painting represents a comprehensive vision of the entire universe.

The exquisite brocades, furs, and silks are shown in an extraordinarily lifelike and brilliant way, a way that confirms their reality, their tangibility. On the other hand, the reliefs and sculptures on the capitals in the background and on the Virgin's throne all allude to Christ's salvation of humanity. The depictions on the throne of Adam and Eve, Cain killing Abel, and Samson fighting the lion, together with the depiction on the capitals of Abraham sacrificing Isaac, create an Old Testament framework which allows the observer to reflect on the mercy of God, who sent his son, Christ the Redeemer, into the world. Redemption from sin (Cain killing his brother) is possible only through the power of faith (Samson overpowering the lion). The goodness and grace of God "at the moment of truth" (Abraham sacrificing Isaac) serves as proof of the redeeming power and presence of servants of God both celestial (St. George) and mortal (Canon van der Paele).

This is how van der Paele might have expressed the message of the painting-that paradise was at hand-a message confirmed by its being set in a very real but also sacred context. The Virgin is pictured holding a nosegay and her son a parrot - unmistakable echoes of the Garden of Eden - and both figures have turned to face the meditating canon.

In the most substantial early source on him, a 1454 biography by the Genoese humanist Bartolomeo Facio (De viris illustribus), Jan van Eyck was named "the leading painter" of his day. Facio places him among the best artists of the early 15th century, along with Rogier van der Weyden, Gentile da Fabriano, and Pisanello. It is particularly interesting that Facio shows as much enthusiasm for Netherlandish painters as he does for Italian painters. This text also sheds light on aspects of Jan van Eyck's production now lost, citing a bathing scene as well as a world map which van Eyck painted for Philip the Good. Facio also recorded that van Eyck was a learned man, and that he was versed in the classics, particularly the writings of Pliny the Elder about painting. This is supported by records of an inscription from Ovid's Ars Amatoria, which was on the now-lost original frame of the Arnolfini Double Portrait, and by the many Latin inscriptions on his paintings, using the Roman alphabet, then reserved for educated men. Jan van Eyck likely had some knowledge of Latin for his many missions abroad on behalf of the Duke.

Jan van Eyck died in Bruges in 1441 and was buried there in the Church of Saint Donatian (destroyed during the French Revolution).

These two small pictures conjure up a veritable microcosm. Every detail is observed with equal interest - from the alpine landscape to the slender body of Christ and the emotions of the various figures. The raised lettering on the original frames forms quotations from Isaiah on the Crucifixion and from Revelations and Deuteronomy on the Last Judgment.

_ca_1425.jpg)

_ca_1430.jpg)

_1432.jpg)

The identity of the sitter has been the subject of considerable speculation. It would seem logical to expect the strange name which someone appears to have lettered onto the stone in Greek (Tymotheos) to provide a clue. In fact, the name did not occur in the Netherlands before the Reformation which led experts to see it as a scholarly humanist metonym to link the sitter with an eminent figure in Classical antiquity.

An inscription, not unlike an epitaph, and yet evidently referring to a living person is chiseled on the parapet: LEAL SOUVENIR (loyal remembrance).

_ca_1435.jpg)

_ca_1437.jpg)

_ca_1437.jpg)

The attention which Van Eyck focused upon the tender embrace of mother and child is characteristic of late-medieval devotion. The artist depicts the paradisiacal garden and other symbols of the Virgin such as the fountain, the rose and the iris. Angels hold up a gorgeous brocade cloth behind the mother and child as a symbol of honor. The symbolism of the colors used in the painting serves to heighten its spiritual message.

Saint Barbara is surprising because of its graphical qualities and its unusual technique, and the fact that it is not an ordinary painting. Numerous experts have tried to determine whether it is in fact an unfinished painting, a grisaille, or a finished drawing. The drawing is executed on a smooth, yellow-brown tinted ground with a stylus, and is finished off with a fine paintbrush. The work has a marbled frame bearing an inscription which tells us the name of the artist and the date of execution, namely 1437. Van Eyck depicts Saint Barbara with her prayer-book and palm, seated before a late-gothic tower which is in the process of construction.

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.