Disclaimer

Henry Tudor

1491 - 1547

Henry the Eighth, by the Grace of God, King of England and France, Defender of the Faith and Lord of Ireland

Rex: 1509 - 1547

Henry VIII was born at Greenwich on 28 June 1491, the second son of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York. He became heir to the throne on the death of his elder brother, Prince Arthur, in 1502 and succeeded in 1509.

Henry VII

Elizabeth of York

In his youth he was athletic and highly intelligent. A contemporary observer described him thus: 'he speaks good French, Latin and Spanish; is very religious; heard three masses daily when he hunted ... He is extremely fond of hunting, and never takes that diversion without tiring eight or ten horses ... He is also fond of tennis.'

Henry's scholarly interests included writing both books and music, and he was a lavish patron of the arts.

Henry Tudor: 1509

He was an accomplished player of many instruments and a composer. Greensleeves, the popular melody frequently attributed to him is, however, almost certainly not one of his compositions.

As the author of a best-selling book (it went through some 20 editions in England and Europe) attacking Martin Luther and supporting the Roman Catholic Church, in 1521 Henry was given the title 'Defender of the Faith' by the Pope.

Author of 'In Defense of the Seven Sacraments'

From his father, Henry VIII inherited a stable realm with the monarch's finances in healthy surplus - on his accession, Parliament had not been summoned for supplies for five years. Henry's varied interests and lack of application to government business and administration increased the influence of Thomas Wolsey, an Ipswich butcher's son, who became Lord Chancellor in 1515.

Wolsey became one of the most powerful ministers in British history (symbolised by his building of Hampton Court Palace - on a greater scale than anything the king possessed). Wolsey exercised his powers vigorously in his own Court of Chancery and in the increased use of the Council's judicial authority in the Court of the Star Chamber.

Cardinal Wolsey at Christ Church: 1526

Wolsey was also appointed Cardinal in 1515 and given papal legate powers which enabled him to by-pass the Archbishop of Canterbury and 'govern' the Church in England.

Henry's interest in foreign policy was focused on Western Europe, which was a shifting pattern of alliances centred round the kings of Spain and France, and the Holy Roman Emperor. (Henry was related by marriage to all three - his wife Catherine was Ferdinand of Aragon's daughter, his sister Mary married Louis XII of France in 1514, and the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V was Catherine's nephew.)

Field of the Cloth of Gold: 1520

An example of these shifts was Henry's unsuccessful Anglo-Spanish campaigns against France, ending in peace with France in 1520, when he spent huge sums on displays and tournaments at the Field of the Cloth of Gold.

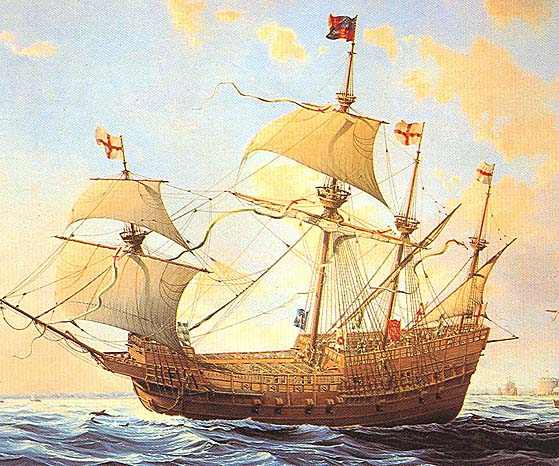

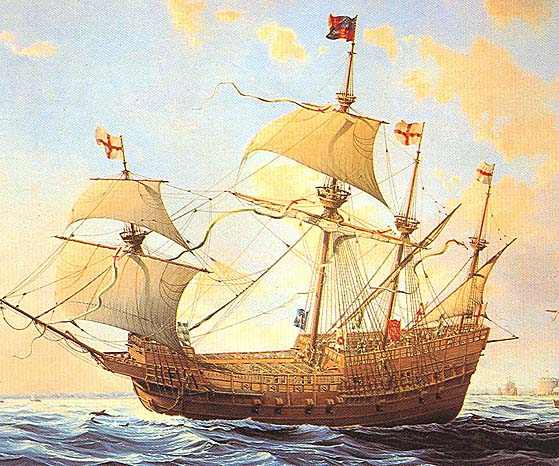

Henry also invested in the navy, and increased its size from 5 to 53 ships (including the Mary Rose, the remains of which lie in the Portsmouth Naval Museum).

HMS Mary Rose

The second half of Henry's reign was dominated by two issues very important for the later history of England and the monarchy: the succession and the Protestant Reformation, which led to the formation of the Church of England.

Henry had married his brother's widow, Catherine of Aragon, in 1509. Catherine had produced only one surviving child - a girl, Princess Mary, born in 1516. By the end of the 1520s, Henry's wife was in her forties and he was desperate for a son.

Catherine of Aragon

The youngest surviving child of the 'Catholic Kings' of Spain, Catharine was born on 16 December 1485, the same year that Henry VII established the Tudor dynasty. At the age of three, she was betrothed to his infant son, Prince Arthur. In 1501, shortly before her sixteenth birthday, Catharine sailed to England. But her marriage to Arthur lasted less than six months and was supposedly never consummated. Catharine was then betrothed to Arthur's younger brother, Prince Henry. When he became king in 1509, at the age of eighteen, he promptly married Catharine and they lived together happily for many years. But their marriage produced just one living child, a daughter called Mary, and Henry was desperate for a male heir. He also fell deeply in love with another woman. Cast aside, Catharine fought against great odds to deny Henry an annulment. But the king would not be denied and when the Catholic Church would not grant the annulment, he declared himself head of a new English church. Catharine was banished from court and died on 7 January 1536, broken-hearted but still defiant.

Mary Tudor: 1544

The Tudor dynasty had been established by conquest in 1485 and Henry was only its second monarch. England had not so far had a ruling queen, and the dynasty was not secure enough to run the risk of handing the Crown on to a woman, risking disputed succession or domination of a foreign power through marriage.

Henry had anyway fallen in love with Anne Boleyn, the sister of one of his many mistresses, and tried to persuade the Pope to grant him an annulment of his marriage on the grounds that it had never been legal.

Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn is one of the most famous queens in English history, though she ruled for just three years. The daughter of an ambitious knight and niece of the duke of Norfolk, Anne spent her adolescence in France. When she returned to England, her wit and style were her greatest charms. She had a circle of admirers and became secretly engaged to Henry Percy. She also entered the service of Catharine of Aragon. But she soon caught the eye of Henry VIII. He ordered Percy from court and tried to make Anne his mistress. She refused. Her sister, Mary, had been the king's mistress and gained little from it but scandal. Her hopes with Percy dashed, Anne demanded that the king marry her. She waited nearly seven years for Henry to obtain an annulment. It finally took an irrevocable breach with the Holy See before they wed in 1533. But she was unable to give Henry the son he desperately needed and their marriage ended tragically for Anne. She was executed on patently false charges of witchcraft, incest and adultery on 19 May 1536. Her daughter, Elizabeth, would become England's greatest queen.

Royal divorces had happened before: Louis XII had been granted a divorce in 1499, and in 1527 James IV's widow Margaret (Henry's sister) had also been granted one. However, a previous Pope had specifically granted Henry a licence to marry his brother's widow in 1509.

Nota Bene: We should also make note of the fact that Charles V had sent an army to Rome to make sure the Pope did not grant Henry a divorce.

In May 1529, Wolsey failed to gain the Pope's agreement to resolve Henry's case in England. All the efforts of Henry and his advisers came to nothing; Wolsey was dismissed and arrested, but died before he could be brought to trial.

Thomas More: 1527

More, fully devoted to Henry and to the cause of royal prerogative, initially cooperated with the king's new policy, denouncing Wolsey in Parliament and proclaiming the opinion of the theologians at Oxford and Cambridge that the marriage of Henry to Catherine had been unlawful. But as Henry began to deny the authority of the Pope, More's qualms grew.

Nota Bene: Thomas More replaced Wolsey as Lord Chancelor and also failed to obtain a divorce for Henry. He would eventually lose his life for refusing to recognize the legality of the English Divorce.

Since the attempts to obtain the divorce through pressure on the papacy had failed, Wolsey's eventual successor Thomas Cromwell (Henry's chief adviser from 1532 onwards) turned to Parliament, using its powers and anti-clerical attitude (encouraged by Wolsey's excesses) to decide the issue.

The result was a series of Acts cutting back papal power and influence in England and bringing about the English Reformation.

In 1532, an Act against Annates - although suspended during 'the king's pleasure' - was a clear warning to the Pope that ecclesiastical revenues were under threat.

In 1532, Thomas Cranmer was promoted to Archbishop of Canterbury and, following the Pope's confirmation of his appointment, in May 1533 Cranmer declared Henry's marriage invalid; Anne Boleyn was crowned queen a week later.

The Pope responded with excommunication, and Parliamentary legislation enacting Henry's decision to break with the Roman Catholic Church soon followed. An Act in Restraint of Appeals forbade appeals to Rome, stating that England was an empire, governed by one supreme head and king who possessed 'whole and entire' authority within the realm, and that no judgements or excommunications from Rome were valid.

An Act of Submission of the Clergy and an Act of Succession followed, together with an Act of Supremacy (1534) which recognized that the king was 'the only supreme head of the Church of England called Anglicana Ecclesia'.

The breach between the king and the Pope forced clergy, office-holders and others to choose their allegiance - the most famous being Sir Thomas More, who was executed for treason in 1535.

The other effect of the English Protestant Reformation was the Dissolution of Monasteries, under which monastic lands and possessions were broken up and sold off. In the 1520s, Wolsey had closed down some of the small monastic communities to pay for his new foundations (he had colleges built at Oxford and Ipswich).

In 1535-36, another 200 smaller monasteries were dissolved by statute, followed by the remaining greater houses in 1538-40; as a result, Crown revenues doubled for a few years.

Nota Bene: One needs to be careful when she or he looks at the English Reformation. Henry's actions were not solely based on the king's desire for a divorce but also by a desire to establish national autonomy and sovereignty within England. To not recognize the Reformation especially in England as a political struggle to establish royal authority and national independence does an intellectual disservice to the political and religious realities of the 16th Century.

Senex Magister

Henry's second marriage had raised hopes for a male heir. Anne Boleyn, however, produced another daughter, Princess Elizabeth, and failed to produce a male child. Henry got rid of Anne on charges of treason (presided over by Thomas Cromwell) which were almost certainly false, and she was executed in 1536. In 1537 her replacement, Henry's third wife Jane Seymour, finally bore him a son, who was later to become Edward VI. Jane died in childbed, 12 days after the birth in 1537.

Jane Seymour: 1536

Henry VIII had six wives but only one gave him a son. Jane Seymour fulfilled her most important duty as queen, but she was never crowned and died just twelve days after the long and arduous birth. She was Henry's third wife and seems never to have made much of an impression upon anyone except the king. Her meek and circumspect manner was in distinct contrast to Henry's second wife, the sharp-tongued Anne Boleyn. Jane had served as lady-in-waiting to Anne and she supplanted her in much the same way Anne had replaced Catharine of Aragon in Henry's affections. We will never know if Jane sought the king's favor or was a frightened pawn of her family and the king's desire. But we do know that she bravely sought pardons for those involved in the Pilgrimage of Grace revolt in 1536. Rebuked by the king, and mindful of the fates of his first two wives, she retired into a quiet and decorous role. The triumphant birth of her son Edward allowed her two ambitious brothers into the king's inner circle; however, both would be executed during Edward's reign.

Although Cromwell had proved an effective minister in bringing about the royal divorce and the English Reformation, his position was insecure. The Pilgrimage of Grace, an insurrection in 1536, called for Cromwell's dismissal (the rebels were put down) but it was Henry's fourth, abortive and short-lived marriage to Anne of Cleves that led to Cromwell's downfall. Despite being made Earl of Essex in 1540, three months later he was arrested and executed.

Anne of Cleves: ca 1539

Anne of Cleves was the fourth wife of King Henry VIII; it was a very brief marriage, to the astonishment of all observers but the relief of both spouses. Henry infamously referred to his bride as a 'Flanders mare' and told courtiers and ambassadors that he could not perform his husbandly duties because of Anne's appearance. Anne's reaction to Henry's physical charms was not recorded, but she agreed to an annulment very quickly and remained in England for the rest of her life. Henry was grateful for her cooperation and granted her a generous income and several homes, including Hever Castle. Anne enjoyed an independent lifestyle denied most women, often visiting Henry's court as an honored guest. Her fondness for English ale and gambling were her only vices. Along with her successor as Henry's wife, Catherine Howard, Anne remains a mysterious figure about whom too little is known. Had she and Henry remained married and had children, the course of English history might have changed dramatically. But the mysteries of physical attraction denied Anne her place on the throne, ended the brilliant career of Thomas Cromwell, and thrust the king into the arms of his ill-fated fifth queen, Catherine Howard.

Henry made two more marriages, to Catherine Howard (executed on grounds of adultery in 1542) and Catherine Parr (who survived Henry to die in 1548).

Catherine Howard: 1540-41

Catherine Howard was a cousin of Henry VIII's ill-fated second queen, Anne Boleyn; and like Anne, Catherine would die on the scaffold at Tower Green. Her birthdate is unknown, but her father was the younger brother of the duke of Norfolk. Though personally impoverished, Catherine had a powerful family name and thus secured an appointment as lady-in-waiting to Henry's fourth queen, Anne of Cleves. While at court, she caught the eye of the middle-aged king and became a political pawn of her family and its Catholic allies. Catherine's greatest crime was her silliness. Raised in the far too permissive household of her grandmother, she was a flirtatious and emotional girl who rarely understood the consequences of her actions. She made the mistake of continuing her girlish indiscretions as queen. Henry was besotted with her, calling her his 'Rose without a Thorn' and showering her with gifts and public affection. Catherine was understandably more attracted to men her own age and, after just seventeen months of marriage to the king, she was arrested for adultery. The distraught king at first refused to believe the evidence but it was persuasive. Unlike Anne Boleyn, Catherine had betrayed the king. She was beheaded on 13 February 1542, only nineteen or twenty years old. The drama of her execution lends gravity to a brief life which would otherwise pass unnoticed.

Katherine Parr

Katharine Parr was the sixth and last wife of King Henry VIII, destined to outlive the mercurial ruler. She was already twice-widowed and childless when they wed in 1543; she was also in love with Thomas Seymour, the brother of Henry's third queen Jane. But the king's will was law and Katharine bowed to his demands with grace. She was an admirable wife to Henry and a loving stepmother to his two youngest children, Elizabeth and Edward. She was also the most intellectual of Henry's wives, caught up in the turbulent religious climate of the times. And it was this passionate interest in theology which nearly ended her life, for the king was old and sickly but still capable of destroying those closest to him. Katharine saved herself and earned Henry's respect enough to be appointed Regent of England during his military campaign in Boulogne. Upon his death in 1547, she married Seymour with indecent haste, the only one of four husbands she had chosen herself. Her greatest achievement was the popularity of her devotional works; they were 16th century bestsellers and capture Catharine's complex and abiding piety.

None produced any children. Henry made sure that his sole male heir, Edward, was educated by people who believed in Protestantism rather than Catholicism because he wanted the anti-papal nature of his reformation and his dynasty to become more firmly established.

After Cromwell's execution, no leading minister emerged in the last seven years of Henry's reign. Overweight, irascible and in failing health, Henry turned his attention to France once more.

Despite assembling an army of 40,000 men, only the town of Boulogne was captured and the French campaign failed. Although more than half the monastic properties had been sold off, forced loans and currency depreciation also had to be used to pay for the war, which contributed to increased inflation. Henry died in London on 28 January 1547.

To some, Henry VIII was a strong and ruthless ruler, forcing through changes to the Church-State relationship which excluded the papacy and brought the clergy under control, thus strengthening the Crown's position and acquiring the monasteries' wealth.

However, Henry's reformation had produced dangerous Protestant-Roman Catholic differences in the kingdom. The monasteries' wealth had been spent on wars and had also built up the economic strength of the aristocracy and other families in the counties, which in turn was to encourage ambitious Tudor court factions.

Significantly, Parliament's involvement in making religious and dynastic changes had been firmly established. For all his concern over establishing his dynasty and the resulting religious upheaval, Henry's six marriages had produced one sickly son and an insecure succession with two princesses (Mary and Elizabeth) who at one stage had been declared illegitimate - none of whom were to have children.

Henry VIII: ca 1536

Henry VIII, ca 1536, by Hans Holbein the Younger. This is the quintessential portrait of Henry VIII. It is perhaps the earliest image of the king by Holbein. It is so beautifully detailed that close inspection is necessary. The cloth of gold sleeve and the intricate pattern of the cloth of silver doublet are perfectly done. Real gold was used to detail the sleeve and the king's jewelry.

The portrait was done around the time of Anne Boleyn's execution, in the midst of the dissolution of the monasteries and before Henry's long-awaited son was born. The king's figure and magnificent apparel are proof of his authority. But Holbein's portrait is not flattering; Henry appears guarded and suspicious, and quite unapproachable. This portrait is part of the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection.

Henry VIII: ca 1536

Henry VIII, ca 1536, after Hans Holbein the Younger. This portrait is a copy of the Holbein portrait above. It is held by the NPG, London.

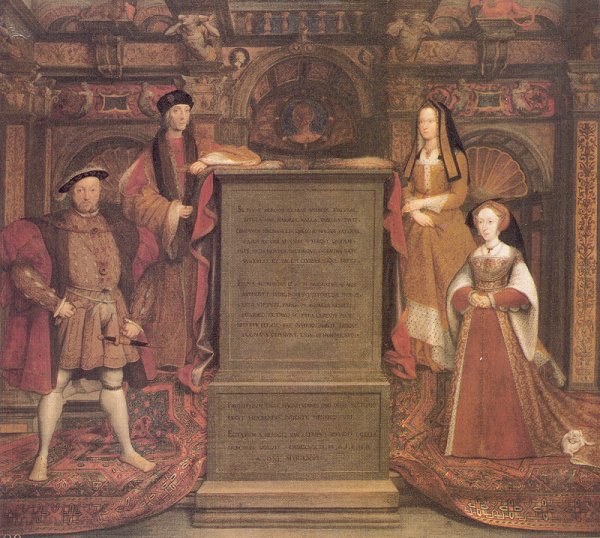

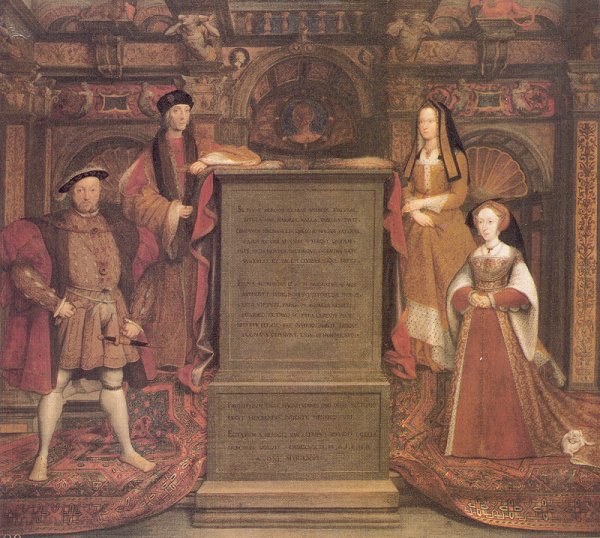

Whitehall Mural

In 1537, Henry commissioned Hans Holbein the Younger to create a mural of the Tudor dynasty to commemorate the birth of his son and heir, Edward. It was the only mural which Holbein made in England. It originally occupied an entire wall in Whitehall Palace, which had been designated the official residence of the monarch just a year earlier. The mural was destroyed during a palace fire in 1698. Luckily, King Charles II had already commissioned a small copy thirty years before by the Flemish artist van Leemput.

The mural features Henry standing before (and dwarfing) the figure of his father, King Henry VII. On the other side, Jane Seymour, Henry's third wife and the mother of his son, stands before Elizabeth of York. If we accept Leemput's copy as a faithful reproduction, the main alteration Holbein made from the sketch to the mural is making Henry VIII face the viewer directly. In the sketch, he is shown three-quarter face, like the other figures. The alteration to full-face gives Henry an even more commanding presence. The influence of the mural upon subsequent portraits of Henry cannot be overestimated.

Henry VIII and the Barber Surgeons

Henry VIII and the Barber-Surgeons, 1540, by Hans Holbein the Younger. This painting was commissioned by the Barber-surgeons.

Henry VIII: ca 1540

Henry VIII, ca 1540, after Hans Holbein the Younger. This portrait is often mistakenly attributed to Holbein. There are actually very few portraits of Henry VIII which can be attributed to Holbein with complete certainty. Those portraits, however, were impressive enough to influence all other artists who painted the king. And so most of Henry VIII's portraits appear Holbein-esque even when they were not actually painted by Holbein. Consider this portrait - the figure of Henry is clearly derivative of the Holbein mural above. The king faces us directly, one hand clutching a glove and the other resting above a jeweled sword. The rings on his fingers are similar as well; the most obvious difference is the color of his sleeves. This portrait can be viewed at the Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica in Rome.

Henry VIII: ca 1540

Henry VIII, ca 1540, after Hans Holbein the Younger. This full-length portrait of the king (once again, we have the familiar Holbein pose of one hand clutching a glove and the other resting above a jeweled sword) is part of the Royal Collection.

Henry VIII: ca 1540

Henry VIII, ca 1540, after Hans Holbein the Younger. This is another anonymous portrait clearly inspired by Holbein's work.

Henry VIII: ca 1542

Henry VIII, ca 1542, unknown artist. This portrait is most remarkable, I think, in its depiction of Henry's apparel. It is quite different from most portraits of the king. The jewelry, lavish embroidery, and fur are proof of Henry's great wealth and authority. It was painted during his brief marriage to his fifth wife, Catherine Howard. It can be viewed at the NPG, London.

Henry VIII: ca 1545

Henry VIII, ca 1545, by Hans Eworth. This full-length portrait borrows much from Holbein's iconic portrayal of Henry; the king stands in the familiar pose (yet again, we have one hand clutching a glove and the other resting above a jeweled sword.) Eworth was the favorite court painter of Henry's daughter, Queen Mary I.

Henry VIII in Old Age

Henry VIII in old age. This anonymous engraving is an unattractive but accurate portrayal of Henry in his mid-50s.

Battle of the Spurs: 1513

The Battle of the Spurs, 1513. This is a cropped detail from the painting which commemorates an English victory against France. It was during this campaign that Henry's close friendship with Cardinal Thomas Wolsey began. Henry's figure is in the center, accepting the surrender of a French Lord.

This page is the work of Senex Magister

Return to Persona Historiae

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.