Henry II of England

1154-1189

King Henry II:

Artist's Impression ca 1620

Henry II, first of the Angevin Kings, was one of the most effective of all England's monarchs. He came to the throne amid the anarchy of Stephen's reign and promptly brought his rebellious barons under royal control. He refined Norman government and created a capable, self-standing bureaucracy. His energy was equaled only by his ambition and intelligence. Henry survived wars, rebellion, and controversy to successfully rule one of the Middle Ages' most powerful kingdoms.

The Angevin Empire

Henry was raised in the French Province of Anjou and first visited England in 1142 to defend his mother's claim to the disputed throne of Stephen. His continental possessions were already vast before his coronation: He acquired Normandy and Anjou upon the death of his father in September 1151, and his French holdings more than doubled with his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine (ex-wife of King Louis VII of France). In accordance with the Treaty of Wallingford, a succession agreement signed by Stephen and Matilda in 1153, Henry was crowned in October 1154. The continental empire ruled by Henry and his sons included the French counties of Brittany, Maine, Poitou, Touraine, Gascony, Anjou, Aquitaine, and Normandy. Henry was technically a feudal vassal of the King of France but, in reality, owned more territory and was more powerful than his French lord. Although King John (Henry's son) lost most of the English holdings in France, English kings laid claim to the French throne until the fifteenth century. Henry also extended his territory in the British Isles in two significant ways. First, he retrieved Cumbria and Northumbria from Malcolm IV of Scotland and settled the Anglo-Scot border in the North. Secondly, although his success with Welsh campaigns was limited, Henry invaded Ireland and secured an English presence on the island.

Stephen of England

English and Norman barons in Stephen's reign manipulated feudal law to undermine royal authority; Henry instituted many reforms to weaken traditional feudal ties and strengthen his position. Unauthorized castles built during the previous reign were razed. Monetary payments replaced military service as the primary duty of vassals. The Exchequer was revitalized to enforce accurate record keeping and tax collection. Incompetent sheriffs were replaced and the authority of royal courts was expanded. Henry empowered a new social class of government clerks that stabilized procedure - the government could operate effectively in the king's absence and would subsequently prove sufficiently tenacious to survive the reign of incompetent kings. Henry's reforms allowed the emergence of a body of common law to replace the disparate customs of feudal and county courts. Jury trials were initiated to end the old Germanic trials by ordeal or battle. Henry's systematic approach to law provided a common basis for development of royal institutions throughout the entire realm.

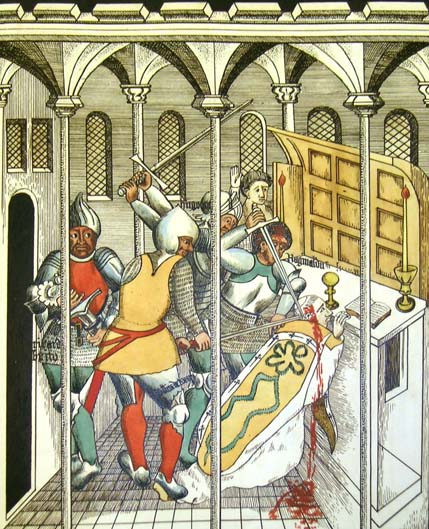

The process of strengthening the royal courts, however, yielded an unexpected controversy. The church courts instituted by William the Conqueror became a safe haven for criminals of varying degree and ability, for one in fifty of the English population qualified as clerics. Henry wished to transfer sentencing in such cases to the royal courts, as church courts merely demoted clerics to laymen. Thomas Beckett, Henry's close friend and Chancellor since 1155, was named Archbishop of Canterbury in June 1162 but distanced himself from Henry and vehemently opposed the weakening of church courts. Beckett fled England in 1164, but through the intervention of Pope Adrian IV (the lone English pope), returned in 1170. He greatly angered Henry by opposing to the coronation of Prince Henry. Exasperated, Henry hastily and publicly conveyed his desire to be rid of the contentious Archbishop - four ambitious knights took the king at his word and murdered Beckett in his own Cathedral on December 29, 1170. Henry endured a rather limited storm of protest over the incident and the controversy passed.

Murder of Archbishop Thomas Becket

Henry's plans of dividing his myriad lands and titles evoked treachery from his sons. At the encouragement - and sometimes because of the treatment - of their mother, they rebelled against their father several times, often with Louis VII of France as their accomplice. The deaths of Henry the Young King in 1183 and Geoffrey in 1186 gave no respite from his children's rebellious nature; Richard, with the assistance of Philip II Augustus of France, attacked and defeated Henry on July 4, 1189 and forced him to accept a humiliating peace. Henry II died two days later, on July 6, 1189.

A couple quotes from historic manuscripts shed a unique light on Henry, Eleanor, and their sons.

From Sir Winston Churchill, 1675: "Henry II Plantagenet, the very first of that name and race, and the very greatest King that England ever knew, but withal the most unfortunate . . . his death being imputed to those only to whom himself had given life, his ungracious sons. . ."

From Sir Richard Baker, A Chronicle of the Kings of England: Concerning endowments of mind, he was of a spirit in the highest degree generous . . . His custom was to be always in action; for which cause, if he had no real wars, he would have feigned . . . To his children he was both indulgent and hard; for out of indulgence he caused his son Henry to be crowned King in his own time; and out of hardness he caused his younger sons to rebel against him . . . He married Eleanor, daughter of William Duke of Guienne, late wife of Louis the Seventh of France. Some say King Louis carried her into the Holy Land, where she carried herself not as a holy wife, but led a licentious life; and, which is the worst kind of licentiousness, in carnal familiarity with a Turk."

Quoted From: Britannia: Monarchs of Britain

This next section on Henry II whuch comes from BBC History, though some of the material is redundant, presents a further insight into this English King.

The Character and Legacy of Henry II

Henry II may be best known as the murderer of Thomas Becket, but he was also a complex man at war with his own family. What forces were at play in Henry's relationship with his wife and sons, and what kind of impact did this have on the monarchy?

Henry II of England Illustration from

Cassel's History of England Published ca 1902

Early influences

Look for the key to Henry's character and look no further than his childhood. The son of Geoffrey of Anjou and Matilda (daughter of Henry I) against whom the barons of England and Normandy rebelled in favor of the usurper Stephen, his childhood was dominated by war and intrigue as his mother and father strove to regain their inheritance. From the age of 9 it was the young Henry to whom that inheritance would fall, and on whom the responsibility of holding it together lay. Consequently, Henry II, King at the age of 22, was mature beyond his years and obsessed with the restoration of his ancestral rights.

Geoffrey of Anjou

Flight of Matilda from Oxford, 1142

Stephen, the last Norman King of England, reigned from 1135 to 1154. He supported the claim

to the throne of Matilda, the daughter of Henry I, before usurping her when Henry died in 1135 and

claiming the throne for himself. England descended into a period of civil war. Stephen was captured after he was defeated by Matilda's army at the Battle of Lincoln in 1141 but was freed in an exchange for the captive Robert, Earl of Gloucester, Matilda's most able lieutenant. Matilda's time on the throne was brief, as a rebellion forced her to flee London. Stephen regained the throne and Matilda was besieged in Oxford, but escaped to Wallingford, camouflaged against the snow by wearing a white cloak. The conflict dragged on until 1148 when Matilda returned to France after the Earl of Gloucester died. Eventually, in 1154, her son was crowned king as Henry II after Stephen died.

Though not handsome, Henry was larger than most men, stocky and quite powerful: a power which came across in his personality. His energy was overwhelming, and his anger legendary, as was his love of hunting. He dressed simply in hunting clothes and was rarely seen either out of the saddle or without a hawk on his arm. Yet paradoxically, this archetypal man of action was an intensely private intellectual. Multi-lingual, he liked to retire with a book, was well-polished in letters and enjoyed scholarly debate. He was also very approachable and never forgot a face. He shunned regular hours and his propensity to change his schedule at short notice was infamous. This often translated into an ability to react to unforeseen circumstances with astonishing rapidity and decisiveness.

He praised loyalty above all else, and his fits of rage against those he deemed as traitors are so melodramatic as to be unbelievable. On more than one occasion, he is said to have foamed at the mouth in a screaming rage, and is even known to have chewed the straw on the floor in seizure. This Henry was frightening, and could reduce international magnates to quivering wrecks. Yet he understood honest opposition and could deal with it equably. What he could not abide was betrayal.

Personal Characteristics

Above all, he was ruthless in pursuit of his rights. He would manipulate the courts, exploit any loophole and even break his word to recover and defend his ancient rights as he saw them. His fundamental policy was to re-establish 'all the rightful customs which were had in the time of King Henry my grandfather, revoking all evil customs which have arisen there since this day.' For Henry, all else came second to this, and his interpretation of these customs was often more rigorous than they actually had been in Henry I's day. This governed all his actions: his foreign policy, his religious policy, his economic and legal policy and even his personal life; at times with disastrous consequences.

This is a very strong indictment of Henry II. I agree that he was not democrat but he did want

to limit or destroy 'ecclesiastical authority' thus asserting the royal authority of the monarch. This was an

essential step in developing a true nation state. His attack on church courts and support of common law and the

beginning of a jury system in English Courts was a first step that will be built upon by future monarchs in England.

~ Senex Magister

In his personal life, his intense privacy seems to have alienated those who were closest to him. The perceived betrayals of first Becket and then Eleanor (both of whom were only acting in the interests of their own personal offices) seem to have hurt him deeply; but the most wounding betrayals were those of his sons. Yet these very betrayals were a natural consequence of his obsession with his rights: he failed to make his sons trust him because he never included them fully in his government.

Passionate, grasping, authoritative, Henry started his reign with a youth's determined arrogance, and ended with a wily old miser's cynicism. He held his kingdom together by force of his personality, but that was his greatest weakness as well as his greatest strength.

Family Background

If people know of Henry II at all, beyond his classic role in Thomas Becket's Martyrdom, it is probably through the Lion in Winter image of a powerful man at odds with his family. This is not incorrect. Henry's relationship with his family was a dramatic and turbulent one that not only shaped the nature of his own reign, but was to have far-reaching effects into the reigns of his successors.

Martyrdom of Thomas Becket

The very nature of Henry's rule was in itself defined by his parentage. Henry was the son of Geoffrey of Anjou and the ex-Empress Matilda of Germany. Matilda was the daughter of Henry I, and was married to Geoffrey in an attempt to recover the marriage alliance between the Anglo-Norman king and the Count of Anjou which had been broken when Henry I's son, William Audelin, died with the sinking of the White Ship in 1120. However, the marriage of a daughter into the House of Anjou was a very different thing in the eyes of his Norman barons to the marriage of a son. It meant that instead of Normandy taking over Anjou, Anjou was effectively taking over Normandy.

King Heny I of England

William Adelin

The White Ship Sinking

So when Henry I died in 1135, the majority of his barons transferred their loyalty to his nephew Stephen of Blois, against Matilda. Henry, born in 1133, grew up during the civil war that followed. At the age of 9, Matilda's claim to the throne was transferred to him after her singular failure to capture the loyalty of the barons. At the same time, Geoffrey of Anjou conquered Normandy and very astutely passed its patrimony to his son, effectively taking himself (an Angevin usurper) out of the picture. So by 1142, Henry had become the focus for opposition to Stephen's inept reign. By the age of 22, he was king of England, his attitudes forged in the fires of civil war.

Eleanor of Aquitaine

On 18th May 1152, the young prince Henry married Eleanor of Aquitaine, the cast-off wife of King Louis VII of France. This in itself was to have far-reaching political consequences, and at the time the marriage scandalized the houses of Europe. Eleanor was eleven years Henry's senior. Strong-willed and impetuous, she was rumored to have had lovers in both Prince Raymond of Antioch and Henry's own father, Geoffrey of Anjou. In fact, Geoffrey strongly advised Henry not to get involved. She was also closely linked to Henry by blood, being within the fifth degree of kinship which was prohibited by the church, and this was precisely the excuse by which Louis had got his marriage to her annulled.

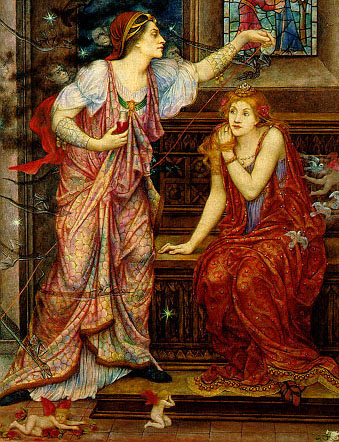

Eleanor of Aquitaine

Louis VII of France

Still, the marriage worked. Their characters complimented each other: Eleanor was a powerful enough personality to hold her own in Henry's company, and was able to act as regent for him when he was away. She bore him 6 children who survived: among them four sons, Henry the Younger, Richard, Geoffrey and John. Yet, like Henry himself, she was fiercely protective of her inheritance, and valued it above loyalty to her husband. This would inevitably result in friction, with Eleanor supporting her sons against their father in defense of Aquitaine.

Contemporary chroniclers failed to understand this driving force within her, and interpreted her 'fickleness' as a variety of women's perceived weaknesses. The most persistent rumor was that Eleanor turned against her husband out of jealousy over his infidelities. Henry undoubtedly had two bastards, Geoffrey 'Plantagenet' and William 'Longsword', and there is also no doubt that the great love of his life was Rosamund Clifford, with whom he took up in 1173 and who died in 1176. Henry is supposed to have contemplated divorcing Eleanor for Rosamund in 1175, and wagging tongues suggested that Eleanor poisoned her the year after. It has also been suspected that Henry had a liaison with Alice, daughter of King Louis, who had been married to Henry the Younger and was then betrothed to Richard for years while she remained in the custody of Henry.

The Rose Of The World

"She hath a waist, a slender waist

as slim as my silver cane

I would not for ten thousand worlds

king Henry knew her name"

- Fair Rosamund, traditional

So little is known about her. Four hundred years after her death she was celebrated in lonely ballads, poetry, plays and romantic legends. But then, it was a time of unrequited sonnets and of faerie queens. It was a time of pretty myths.

So little is really known about her:

We know she was called 'Fair'; 'The Rose Of The World'. We know that she was born in 1150 at Clifford Castle, a solemn complex overlooking the River Wye - the living, surging border between England and Wales. Her father was Walter de Clifford. A relative in the distant future would rebel against his king and when caught would be hung in chains outside the tower of his castle until death finally pitied him.

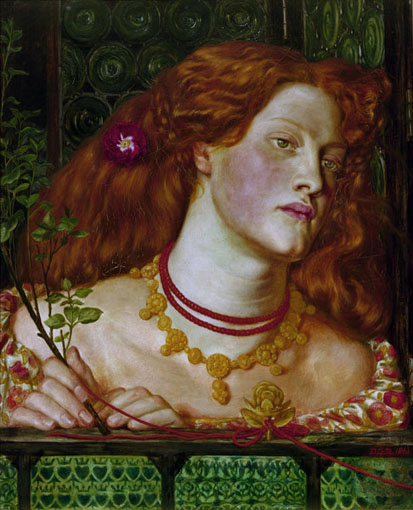

Fair Rosamund

We know that she was the mistress of Henry II, creator of English law, and enemy of the meddlesome priest, Thomas Beckett.

Fair Rosamund Clifford in all probability met the King when her father was poring over maps of Wales with him, devising an itinerary of brutality for that bold country. He loved the daughter, and went to war with the father.

Rosamund was 16. She was soft, gentle and, witnesses agree, exceptionally lovely. She was a calm dream that a warrior king could return to at the end of a violent day. She was everything Henry's wife was not. Eleanor of Aquitaine was wealthy, schooled in the brutal politics of the day, hard and brilliant as a diamond and as courageous as any man: she had sailed to Antioch on crusade with her first husband when she was 25.

In 1166 Eleanor was pregnant with her final child, John - her least inspired effort. She had planned to retreat to Woodstock for her confinement. There she would be shuttered away, still and breathless, the air swaddled in the smells of herbs and dried rushes. But at the last moment she was carried to Beaumont Palace - it has been speculated that this decision is based on her finding that Woodstock already had its lady: Rosamund.

Rosamund Clifford by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Legend says that Woodstock was the site of 'Rosamund's Bower': a garden set at the heart of a maze so subtle and winding that only when she reclined within that living puzzle would she be safe from Eleanor's machinations and jealousies. But she was found with a golden thread; some say it had snagged on Henry's spur, some claim that it had trailed from her box of embroideries.

Eleanor followed that glinting thread, sparking in the sun, amongst the twisted foliage and found her fair nemesis. Spiteful and deadly, she forced the girl to drink a vial of poison - whether she left or chose to watch her die is not revealed.

This terrible myth has been saved comfortably in fiction - like a thorn wrapped in clover. But there was a popular balled, 'Queen Eleanor's Confession' in which Eleanor lies on her deathbed at Whitehall, where:

"The bells they did ring, and the quiristers sing,

And the torches did light them all"

And she decleares her guilt:

"The next vile thing that ere I did

To you I will discover

I poysoned Fair Rosamund,

All in fair Woodstock bower."

Henry's relationship with his rose was made public in 1174. Two years later she retired to a nunnery in Godstow, to fade and dry. She died that same year, lying lonely on her bed - made narrow and hard for her sins. Was it her choice to leave court? Was she thrown out - had Henry found someone else? Was she forced out - was this one of Eleanor's 'good' years, when she held the upper hand over the king? Was she hurried away in secret, sad, in shame, wrapped in a thick woolen cloak against the dank, marshy winds of the Thames, eyes lowered…never, perhaps, daring to look anyone in the face again?

The nuns took care of the final home of Henry's - many say only - love. It became a popular local shrine, laden with flowers and candles, scenting and warming her bones, as the local people came to pray there. If they came to pray at the abbey's high altar, or to The Rose Of The World, no one knows for sure.

Fair Rosamund by John William Waterhouse

In 1191 there was a new king on the throne. Said to have the heart of a lion, he was also a bigot; he preferred war to building, and spent most of his reign on crusade. It was the year that the Bishop of Lincoln stopped to inspect the grounds of Godstow and noticed Rosamund's tomb, its garlands, and worse, its prominent location.

Knowing her story, he immediately demanded that the remains of 'a harlot' be wrenched out of the tomb and buried outside the abbey, 'with the rest, that the Christian religion may not grow into contempt, and that other women, warned by her example, may abstain from illicit and adulterous intercourse'.

England is full of ghosts. Some are in white, some are in clouds of smoke, some are wrapped in chains, some cradle their decapitated heads, some are silent, some weep. Rosamund's ghost has been seen at a local inn that dates to 1472. Originally named 'Ye Sygne of St. John Baptist Head', in 1704 it became 'The Trout Inn'. Perhaps Henry's beautiful fish was finally able to break free of the earth to swim through the currents of the cosmos and the earthly ether.

"Out from the horror of infernall deepes,

My poore afflicted ghost comes here to plaine it:

Attended with my shame that never sleepes,

The spot wherewith my kinde, and youth did staine it:

My body found a grave where to containe it,

A sheete could hide my face, but not my sin,

For Fame finds never tombe t'inclose it in."

- The Complaint of Rosamund, Samuel Daniel, 1592

Quoted From: Rosamund Clifford - Aubrey's Blog

Certainly, it is likely that these rumors contributed to Richard's distrust of his father. But Henry and Eleanor had been to all intents and purposes estranged since the birth of John in 1167, and her actions are always geared towards her sons and Aquitaine. Henry's little peccadilloes were of more interest to the chroniclers than they seem to have been to Eleanor (though the implications of a divorce are likely to have stung her into action).

Henry and His Sons

Henry appears to have viewed his kingdom as a kind of family corporation to be divided between his sons; many historians happily use the term 'federal' to describe its structure. This view was explicitly laid out in his will of 1182, but is likely to have been in place at least 10 years before that. In this grand plan, the central patrimony of England, Normandy and Anjou went to his eldest son, Henry the Younger; Aquitaine was put in the charge of Richard; Geoffrey got Brittany and John was allocated Ireland. However, he did not include them fully enough in the running of the kingdom (this is especially true of Henry the Younger) and failed to keep them adequately informed of his intentions. Intensely private and notoriously scheming, Henry's great mistake was in keeping his sons guessing, until like true Plantagenets, they simply lost patience and tried to take what was rightfully theirs.

The first great family squabble occurred in 1173 when Henry the Younger, aggrieved at his lack of power and egged on by Henry's enemies, rebelled against him. He was joined by his brothers Richard and Geoffrey, and supported by several powerful English barons as well as the kings of France and Scotland. Even Queen Eleanor escaped from house arrest and tried to join him, but was intercepted en route. Henry II's position was more precarious at this point than at any previous time in his reign. If he even appeared to be losing, most of the nobles of England were poised to desert him. He fought a masterful defensive campaign, humiliating the French and Bretons, and crushing any opposition in England, whilst his agents defeated and captured William of Scotland in 1174. Henry the Younger surrendered, and his father, shaken by the experience, acknowledged many of his sons' grievances, assigning revenues to each of them.

Henry the Young, Plantagenet

In 1183, Henry the Younger tried again. Henry's oldest son was something of a dilettante, with a puffed-up idea of his own abilities and importance. When Henry II refused to give him control of Normandy, or any other land that would help pay his debts, he made advances to the barons of Aquitaine. Richard complained and started fortifying his castles when Henry misled and lied. During the negotiations which followed, Henry the Younger attempted to ambush his father at Limoges. Battle lines were drawn: Henry brought up forces to besiege the town, while Henry the Younger was joined by troops from his brother Geoffrey and the new king Philip of France. Forced to flee from Limoges, after robbing the local shrine to pay his troops, Henry the Younger went on the run, moving aimlessly through Aquitaine until he caught dysentery and died. With his death, the rebellion petered out.

Final Years

Henry II was devastated and profoundly shaken by the whole affair. He tried to restructure his kingdom, requiring Richard to give up Aquitaine to John, with the implication that Richard would get Henry the Younger's old inheritance. But Richard was in no mood to trust his father. It is one of the family conferences prompted by this tension that is depicted in the Lion in Winter. Richard's paranoia over Aquitaine was astutely manipulated by King Philip of France, the son of Louis VII, whose overwhelming ambition was to destroy Angevin rule within his kingdom. The inevitable break came in 1189, when Richard and Philip ambushed Henry after a Peace Conference at La Ferté. Not well and sick being close to death, Henry fled towards Anjou; but the final blow was struck when he discovered that the rebels had been joined by his favored youngest son, John. He lapsed into a delirium during a Peace Conference at Ballan near Tours and died on 6th July 1189, aged 56.

It seems a fitting and tragic death, given Henry's history with his family. With the end of his reign came the end of the dream of a federal Angevin empire. In this respect, the great winner from Henry II's reign was King Philip of France, for with the death of the federal ideal, the structural weaknesses of the Angevin empire could be exploited to wrench it from the lackluster hand of a weak ruler. Richard I took all the reins of power into his hands, and despite his absence on crusade, proved a capable and effective ruler, able to hold onto the hugely disparate agglomeration of kingdoms he had inherited. This is more than can be said for John. It was John who failed to maintain the proper vassal/liege relationship with the King of France, who antagonized the barons of Aquitaine and who failed to defend Normandy against the incursions of King Philip.

Richard Coeur de Lion

(19th-Century Portrait of Richard)

No-one could have predicted it at the time, but the ultimate failure of Henry and his family was the failure of the Kings of England to establish themselves as anything more than Kings of Britain.

Quoted From: BBC - History: The Character and Legacy of Henry II

The Widowhood of Eleanor of Aquataine

When Henry died on July 6, 1189, her favorite son Richard ascended the throne of England and one of his first acts was to order the release of his revered mother. He was to prove to be an absentee king and soon after his coronation, inspired no doubt by the tales of his mother's crusade, left England to take part in the Third Crusade. Eleanor escorted his intended bride, Berengaria of Navarre, who was to join him on the crusade, from Spain to Sicily, for their marriage. Their union produced no children. On his return journey, Richard was taken captive and held for ransom. Eleanor campaigned tirelessly for his release, addressing the Pope in an outraged letter of complaint as "Eleanor, by the wrath of God, Queen of England". She personally delivered his ransom.

Berengaria of Navarre

When Richard was mortally wounded at the Siege of Chaluz, she rushed to be with him at the end. On 6th April, 1199 "he ended his earthly day" in her arms and she escorted his body to Fontevrault for burial.

She supported her youngest son John as King of England in preference to her grandson, Arthur of Brittany. Now in her late seventies, Eleanor's travels were far from over, a peace treaty was negotiated between England and France, now ruled by Louis VI's astute and wily son, Phillip Augustus, to be cemented by the marriage of the Dauphin Louis and Eleanor's granddaughter, Blanche, daughter of Alfonso VIII, King of Castile and Eleanor of England, she undertook the journey over the Pyrenees to Castile to escort the bride to France.

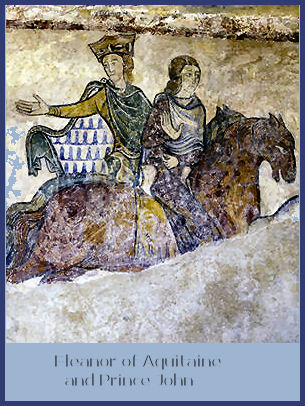

Eleanor of Aquitaine and Prince John

Arthur of Brittany attempted to recover his inheritance from John and in the summer of 1202, besieged his octogenarian grandmother at Mirebeau Castle which she valiantly held for John. Eleanor resorted to delaying tactics, while sending an urgent message to her son for aid. John responded with alacrity, covering the 80 mile distance from Le Mans in 48 hours, he came to the aid of his mother and took Arthur prisoner. Arthur was later murdered at Rouen by his ruthless uncle. Eleanor's reaction to his disappearance has gone unrecorded, although it led Shakespeare to refer to her as a 'a cankered grandam'.

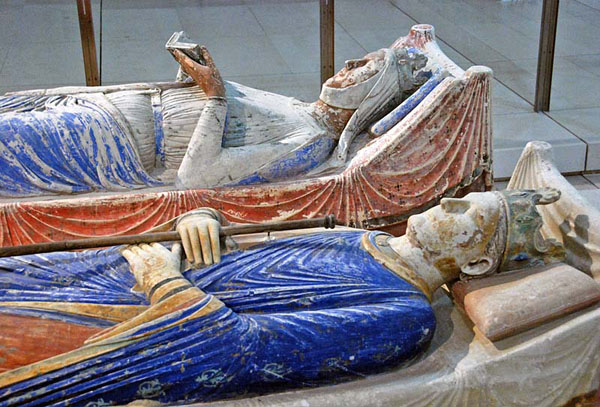

Fontevrault Abbey - Today

Eleanor retired to Fontevrault, where she hoped to find peace and took the veil. Her magnificent constitution was at last exhibiting signs of failing and she was reported to be often unwell, she was visited there by John. Richard's 'saucy castle' Chateau Gaillard, fell to the French and as Phillip began the dismemberment of the crumbling French Angevin Empire, Eleanor sank into a coma, the annals of Fontevrault recorded that she 'existed as one already dead to the world'. Eleanor of Aquitaine died in 1204 and was buried at Fontevrault, the mausoleum of the early Plantagenets, by her husband, Henry II and her best loved son, Richard. Constructed in the thirteenth century, and ravaged by time and revolution, her painted effigy depicts her reading a book, reflecting her love of learning.

Tombs of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine in Fontevraud Abbey

Quoted From: Eleanor of Aquitaine

Return to Persona Historiae

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.