1497 - 1553

_1521_22.jpg)

_1521_22.jpg)

However, despite her newly-acquired wealth and power, Katherine found her marital relations unappealing. She was not pregnant upon marriage, and became repulsed by her husband's grotesque body. (He weighed 300 pounds, about 136 kilograms, at the time, and had an ill-smelling festering ulcer on his thigh that had to be drained daily.) Early in 1541, she embarked upon a light-hearted romance with Henry's favorite male courtier, Thomas Culpepper, whom she initially desired when she came to court two years before. Their meetings were arranged by one of Katherine's older ladies-in-waiting, Lady Rochford, the widow of Anne Boleyn's and Mary Boleyn's brother, George Boleyn.

Meanwhile, Henry and Katherine toured England together in the summer of 1541, and preparations for any signs of pregnancy (which would lead to a coronation) were in place, indicating that the married couple were sexually active with each other. As Katherine's extramarital liaison progressed, people who had witnessed her indiscretions at Lambeth Palace began to contact her for favours. In order to buy their silence, she appointed many of them to her household. Most disastrously, she appointed Henry Mannox as one of her musicians and Francis Dereham as her personal secretary. This led to Katherine's charge of treason and adultery two years after the king married her.

Thomas Cranmer's secretary, Ralph Morice, in a letter to his master, 1540

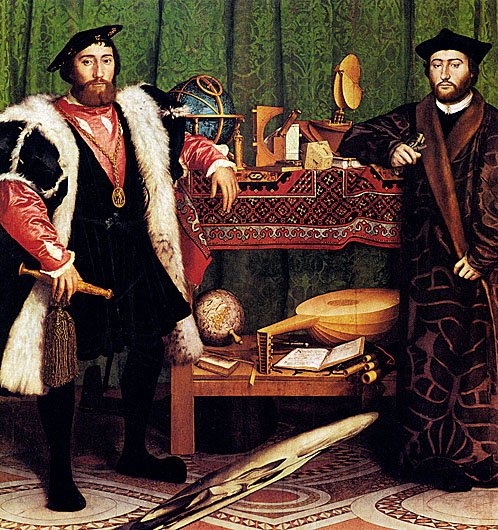

Anne was born at Dusseldorf, the daughter of John III, ruler of the Duchy of Cleves, who died in 1538. After John's death, her brother William became Duke of Julich-Cleves-Berg, bearing the promising epithet "The Rich." In 1526, her elder sister Sybille was married to John Frederick, Elector of Saxony, head of the Protestant Confederation of Germany and considered the "Champion of the Reformation." At the age of 12 (1527), she was betrothed to Francis, son and heir of the Duke of Lorraine while he was only 10, so the betrothal was considered 'unofficial.' While her brother William was a Lutheran, the family's politics made them suitable allies for England's King Henry VIII in the aftermath of the Reformation, and a match with Anne was urged on the king by his chancellor, Thomas Cromwell.

The two were married on 6 January 1540 at the royal Palace of Placentia in Greenwich, London by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, despite Henry's very vocal misgivings. If his bride had objections, she kept them to herself. The phrase "God send me well to keep" was engraved around Anne's wedding ring.

Anne was commanded to leave the Court on June 24 and on July 6 she was informed of her husband's decision to reconsider the marriage. In a short time, Anne was asked for her consent to an annulment, to which she agreed. The marriage was annulled on July 9, 1540, on the grounds both of non-consummation and of her pre-contract to Francis of Lorraine. She received a generous settlement, including Hever Castle, home of Henry's former in-laws, the Boleyn's. Anne of Cleves House, in Lewes, Sussex, is just one of many properties she owned; she never lived there. Made a Princess of England and called "the King's Beloved Sister" by her former husband, Anne remained in England for the rest of her life.

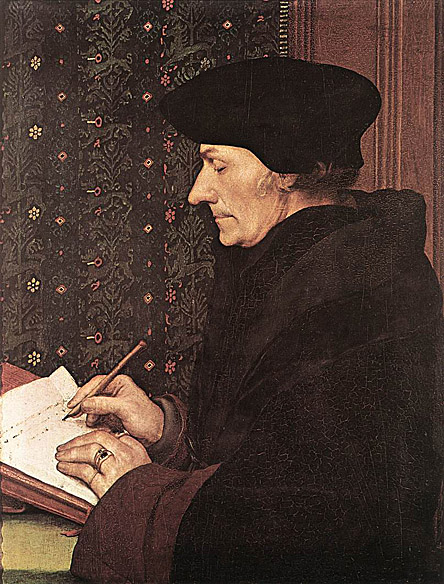

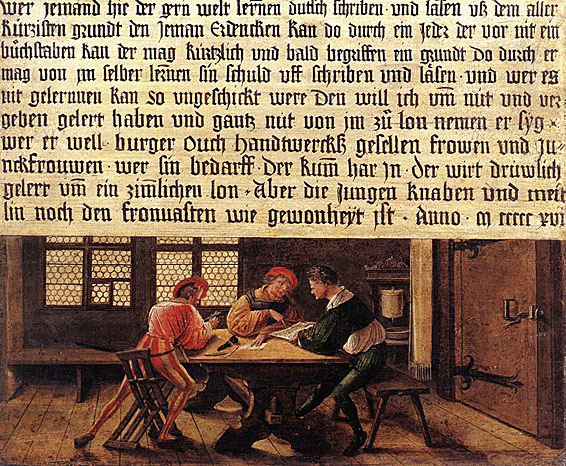

Desiderius Erasmus was a fine man who wrote in a "pure" Latin style and enjoyed the title/name "Prince of the Humanists." He has been called "the crowning glory of the Christian humanists." Renaissance humanists were especially learned and interested in the study of ancient languages. Using humanist techniques he prepared important new Latin and Greek editions of the New Testament which raised questions that would be influential in the Reformation. He also wrote The Praise of Folly, Handbook of a Christian Knight, On Civility in Children, Copia: Foundations of the Abundant Style, and many other works.

Erasmus lived during a time when many learned people were critical of various Christian beliefs and practices. Some such critics ultimately rejected the authority of the pope and developed new theological systems. Erasmus numbered among those Reformers who consistently criticized certain contemporary Christian beliefs and practices but who remained intellectually committed throughout his life to a belief of a Universal Catholic Church and to Papal Authority. He also remained committed to a Catholic doctrine of free will, which many Protestant Reformers rejected in favor of the doctrine of predestination. This middle road disappointed, even angered, leading Protestants, such as Martin Luther, and more fervent papists.

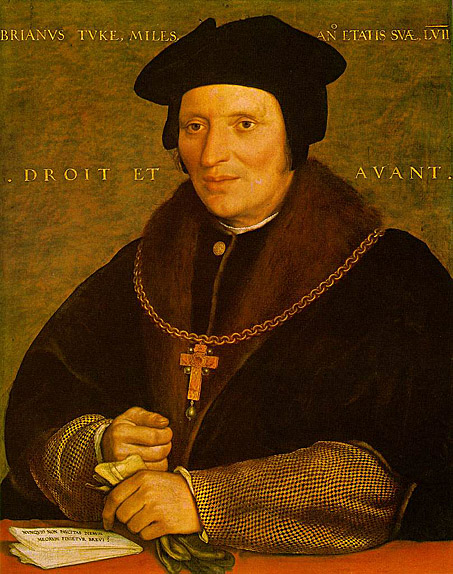

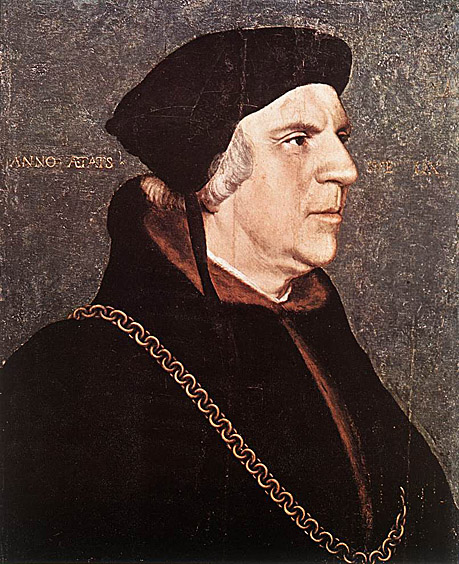

Later he took holy orders, held two livings (Barley and Cottenham), and became Master of the Rolls in 1494, while Henry VII found him a useful and clever diplomatist. He helped to arrange the marriage between Henry's son, Arthur, Prince of Wales, and Catherine of Aragon; he went to Scotland with Richard Foxe, then bishop of Durham, in 1497; and he was partly responsible for several commercial and other treaties with Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor who was also Count of Flanders and Regent Duke of Burgundy on behalf of his son Philip IV of Burgundy.

In 1502 Warham was consecrated Bishop of London and became Keeper of the Great Seal, but his tenure of both these offices was short, as in 1504 he became Lord Chancellor and Archbishop of Canterbury. In 1506 he became chancellor of Oxford University, a role he held until his death. In 1509 the Archbishop married and then crowned Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon.

As archbishop he seems to have been somewhat arbitrary - for example, his actions led to a serious quarrel with Foxe (by then Bishop of Winchester) and others in 1512. This led to his gradually withdrawing into the background after the coronation, resigning the office of Lord Chancellor in 1515, and was succeeded by Wolsey, whom he had consecrated as bishop of Lincoln in the previous year. This resignation was possibly due to his dislike of Henry's foreign policy.

He was present at the Field of the Cloth of Gold in 1520, and assisted Wolsey as assessor during the secret inquiry into the validity of Henry's marriage with Catherine in 1527. Throughout the divorce proceedings Warham's position was essentially that of an old and weary man. He was named as one of the counselors to assist the queen, but, fearing to incur the king's displeasure and using his favorite phrase ira principis mors est, he gave her very little help; and he signed the letter to Clement VII which urged the pope to assent to Henry's wish. Afterwards it was proposed that the archbishop himself should try the case, but this suggestion came to nothing.

He presided over the Convocation of 1531 when the clergy of the province of Canterbury voted 100,000 Pounds to the king in order to avoid the penalties of praemunire, and accepted Henry as supreme head of the church with the saving clause "so far as the law of Christ allows."

In his concluding years, however, the archbishop showed rather more independence. In February 1532 he protested against all acts concerning the church passed by the parliament which met in 1529, but this did not prevent the important proceedings which secured the complete submission of the church to the state later in the same year. Against this further compliance with Henry's wishes Warham drew up a protest; he likened the action of Henry VIII to that of Henry II, and urged Magna Carta in defense of the liberties of the church. He attempted in vain to strike a compromise during the Submission of the Clergy. Warham was munificent in his public, and moderate in his private life. He was buried in the Martyrdom or north transept of Canterbury Cathedral.

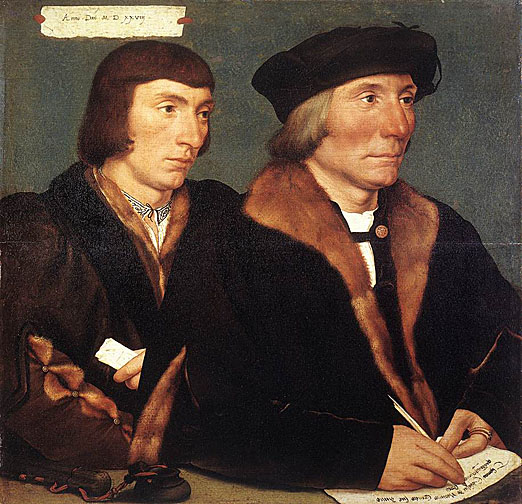

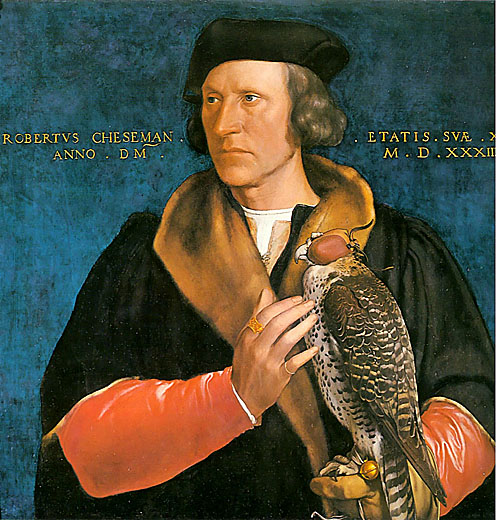

The son of Richard Carew, the Captain of Calais, Nicholas was placed in Henry's household when he was six, and shared the King's education. In the early years of Henry's reign, he came to prominence at court through his skill at jousting, and was renowned for his courage. By 1515, Carew's fame in the lists was such that the King provided him with his own tiltyard at Greenwich. He was knighted some time before 1517.

Carew was popular with the King, who sought his company, but was known in his youth for being something of a gambler. He was one of a number of Henry's companions whom Cardinal Wolsey believed had too much influence over the King. In 1518, Wolsey managed to have Carew sent away from court, replacing him with his own protege Richard Pace. He soon returned, but was removed again, to Calais, in 1519. In 1521 he was given reversion of constable of Wallingford Castle, together with the stewardship of Wallingford. Wolsey finally engineered Carew's dismissal from the Privy Chamber as part of the Eltham Ordinances of 1526.

In 1522, Carew succeeded Sir Henry Guildford as Master of the Horse, a post he held until his death. In the following years he was frequently sent on embassies to Paris. Francis I developed a high regard for Carew, and urged Henry to advance him; the self-avowed 'reprobate' was now a sober politician. In January 1528, to Wolsey's dismay, Sir Nicholas was restored to the Privy Chamber, possibly through the influence of his cousin, Anne Boleyn.

However, Carew started to resent the way Anne used her position as the King's mistress, revealing his sympathy for Queen Katherine and the Princess Mary to the imperial ambassador, Eustace Chapuys. In 1531, angry at the way she had treated his friends, Guildford and the Duke of Suffolk, he began working against her. These maneuvers culminated in 1536, when the reformist Thomas Cromwell made common cause with religious conservatives, such as Carew, to bring Queen Anne down. At this time, Henry chose Carew to fill a vacancy in the Order of the Garter, thus fulfilling a promise made to Francis I.

In late 1538, Cromwell moved against his former allies. Carew was already out of favor at court, having responded angrily to an insult made by the King. When Cromwell presented apparently treasonous letters written by him, Henry was persuaded that Carew had been involved in the Exeter Conspiracy, a supposed plot to depose him. Sir Nicholas was arrested, and executed on 3 March 1539.

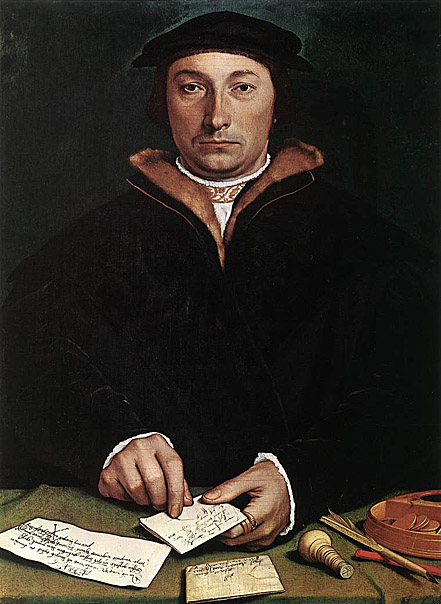

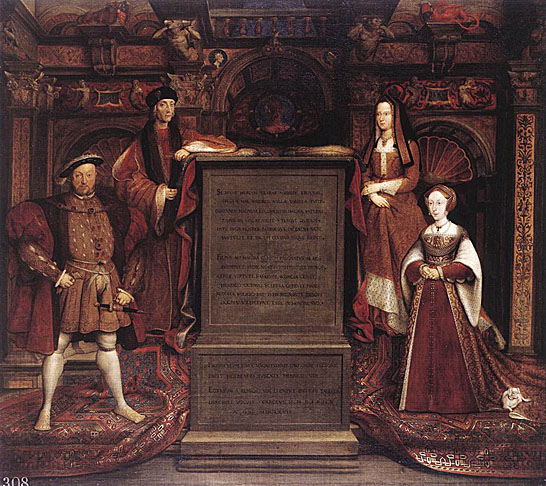

In 1524 he was appointed at Gray's Inn. In the late 1520s he helped Wolsey dissolve thirty monasteries in order to raise funds for Wolsey's grammar school in Ipswich and the Cardinal's College, Oxford. In 1529 Henry VIII summoned a Parliament (later known as the Reformation Parliament) in order to obtain a divorce from Catherine of Aragon. In late 1530 or early 1531 Cromwell was appointed a royal counselor for parliamentary business and by the end of 1531 he was a member of Henry VIII's trusted inner circle. Cromwell became Henry VIII's chief minister in 1532 not through any formal office but by gaining the King's confidence.

Cromwell played an important part in the English Reformation. The parliamentary sessions of 1529-1531 had brought Henry VIII no nearer to annulment. However the session of 1532-Cromwell's first as chief minister-heralded a change of course: key sources of papal revenue were cut off and ecclesiastical legislation was transferred to the King. In the next year's session came the fundamental law of the English Reformation: the Act in Restraint of Appeals of 1533 which forbade appeals to Rome (thus allowing for a divorce in England without the need for the Pope's permission). This was drafted by Cromwell and its famous preamble declared:

Where by divers sundry old authentic histories and chronicles, it is manifestly declared and expressed that this realm of England is an Empire, and so hath been accepted in the world, governed by one Supreme Head and King having the dignity and royal estate of the imperial Crown of the same, unto whom a body politic compact of all sorts and degrees of people divided in terms and by names of Spirituality and Temporality, be bounden and owe to bear next to God a natural and humble obedience.

When Cromwell used the label "Empire" for England he did so in a special sense. Previous English monarchs had claimed to be Emperors in that they ruled more than one kingdom, but in this Act it meant something different. Here the Kingdom of England is declared an Empire by itself, free from "the authority of any foreign potentates". This meant that England was now an independent sovereign nation-state no longer under the jurisdiction of the Pope.

Cromwell was the most prominent of those who suggested to Henry VIII that the king make himself head of the English Church, and saw the Act of Supremacy of 1534 through Parliament. In 1535 Henry VIII appointed Cromwell as his last "Vicegerent in Spirituals". This gave him the power as supreme judge in ecclesiastical cases and the office provided a single unifying institution over the two provinces of the English Church (Canterbury and York). As Henry VIII's vicar-general, he presided over the Dissolution of the Monasteries, which began with his visitation of the monasteries and abbeys, announced in 1535 and begun in the winter of 1536. As a reward, he was created Earl of Essex on 18 April 1540. He is also the architect of the Laws in Wales Acts 1535-1542, which united England and Wales.

Cromwell also became patron to a group of English intellectual humanists whom Cromwell used to promote the English Reformation through the medium of print. These included Thomas Gibson, William Marshall, Richard Morrison, John Rastell, Thomas Starkey, Richard Taverner and John Uvedale. Cromwell commissioned Marshall to translate and print Marsilius of Padua's Defensor Pacis, for which he paid him 20 Pounds.

When Erasmus was trying to retrieve the arrears of his pension from the living in Aldington, Kent, the incumbent refused on grounds that it was his predecessor who had promised to pay his pension. Cromwell sent Erasmus twenty angels and Thomas Bedyll, a friend of Cromwell's, informed Erasmus that Cromwell "favors you exceptionally and everywhere shows himself to be an ardent friend of your name".

Cromwell had supported Henry VIII in disposing of Anne Boleyn and replacing her with Jane Seymour. During his years as Chancellor, Cromwell had created many powerful enemies for himself; mainly due to the inordinate generosity he showed himself when dividing the spoils from the dissolution of the monasteries. His downfall was the haste with which he encouraged the king to re-marry following Jane's premature death. The marriage to Anne of Cleves, a political alliance which Cromwell had urged on Henry VIII, was a disaster, and this was all the opportunity that Cromwell's opponents, most notably the Duke of Norfolk, needed to press for his arrest. While at a Council meeting on 10 June 1540, Cromwell was arrested and imprisoned in the Tower of London. Cromwell was subject to an Act of Attainder and was kept alive by Henry VIII until he could be divorced from Anne.

He was then privately executed at the Tower on 28 July 1540. It is said that Henry VIII intentionally chose an inexperienced executioner -- the teenager made three attempts at chopping Cromwell's head before he succeeded. After execution his head was boiled and then set upon a spike on London Bridge-facing away from the City of London. Edward Hall, a contemporary chronicler, records that Cromwell made a speech on the scaffold stating, among other things, "I die in the traditional faith." (Roman Catholicism), and then "so patiently suffered the stroke of the axe, by a ragged Butcherly miser which Office he performed very poorly".

In 1533 she married by proxy Francesco II Sforza, Duke of Milan, who died in 1535.

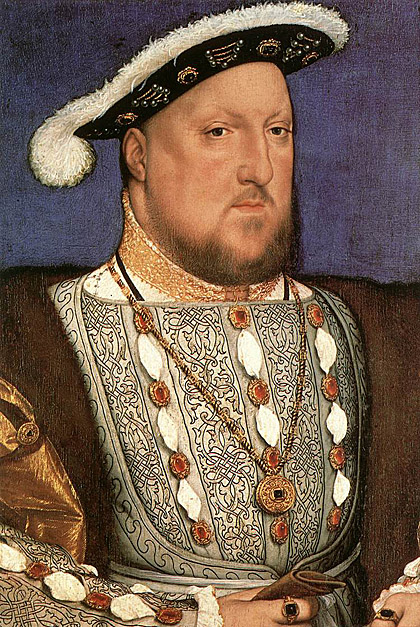

In 1538, German painter Hans Holbein arrived in Brussels to meet Christina. Holbein had been commissioned by Henry VIII of England to paint portraits of noble women who were considered suitable brides. Christina had been mentioned after the death of Jane Seymour in 1537. Upon Holbein's arrival, Christina sat for a portrait, wearing mourning clothes. The English ambassador was arranging for Henry VIII to see the Duchess's likeness in connection with plans to marry her. Christina, then only sixteen years old, made no secret of her opposition to marrying the English king, who by this time had a reputation around Europe for his mistreatment of his wives. She supposedly told the English ambassador that "If I had two heads, one should be at the King of England's disposal."

Christina was also the grand-niece of Henry's first wife Catherine of Aragon through her mother.

Margaret is best remembered for having been a companion of Anne Boleyn, whose family estates lay near the Wyatt's and who later employed Margaret as one of her ladies-in-waiting. A portrait by Hans Holbein the Younger shows a woman presumed to be Margaret at the age of thirty-four, and it is assumed that it was painted around 1540. It is therefore probable that Margaret was very close to Anne in age, being born close to 1506 (while Anne is assumed to have been born around 1507.)

Few question that there was some form of friendship between Lady Margaret and Queen Anne. There is also a strong tradition which states that Margaret's sister, Mary, was also part of the queen's social circle. Certainly Margaret's brother, Thomas Wyatt, fell passionately in love with Anne in the 1520s. Another female favorite of the queen's was Lady Bridget Wingfield, who died in childbed in 1531.

Margaret was one of Anne's chief ladies-in-waiting, and accompanied her to Calais, France in 1532, where it is presumed Anne and Henry VIII made secret plans to marry in the immediate future. It is known that Anne had a lady-in-waiting who "she loves as a sister," and it has been suggested that this lady was Margaret. She was certainly part of the queen's circle of favorites. As Mistress of the Queen's Wardrobe, she would presumably have played a leading part in the decadent social life at court in the mid-1530s, which was fueled by the extravagance of Henry and Anne.

Lady Margaret was sent to attend her royal mistress in the Tower of London in May 1536 when the Queen was arrested on false charges of adultery, treason, and incest. Margaret also attended Anne on the scaffold on May 19, and even received the last gift of a prayer book from her. After Anne was beheaded, Margaret acted as chief mourner at her small funeral. Anne had written a short farewell to Margaret inside the prayer book:

"Remember me when you do pray, that hope doth lead from day to day."

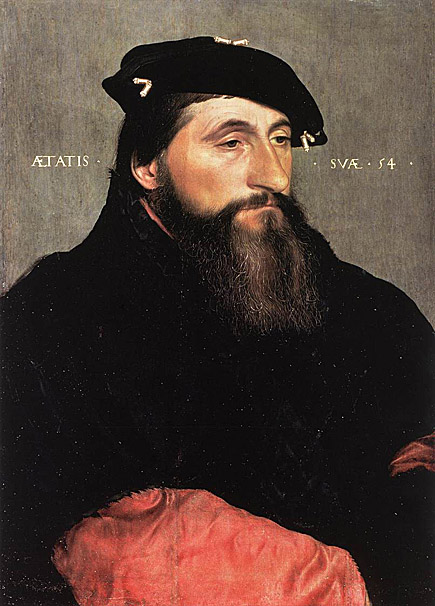

Queen Anne's religious and political vision was more radical than Norfolk's, and their relationship deteriorated throughout 1535 and 1536. Norfolk was perhaps behind the King's affair with Anne's cousin, Margaret Shelton, another of the duke's numerous nieces. Putting his own security before family loyalties, he presided over Queen Anne's trial in 1536, giving a death sentence despite her probable innocence. The next day, he condemned to death his nephew, Anne's brother George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford for the crime of incest with his own sister, the Queen.

Regardless of this tragedy within his family, he used another of his nieces, the teenaged Catherine Howard to strengthen his power at court by orchestrating an affair between her and the 48 year-old king. He used Henry's subsequent marriage to Catherine as an opportunity to dispose of his long-term enemy, Thomas Cromwell who was beheaded in 1540. Queen Catherine's reign was a short one, however, since Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury, discovered that she was already secretly betrothed before her marriage to Henry and had been extremely indiscreet since. Catherine was beheaded in February 1542, and numerous other Howards were imprisoned in the Tower - including the duke's stepmother, brother, two sisters-in-law and numerous servants.

Queen Catherine Howard's execution was the point at which he fell out of favor with King Henry VIII, despite Norfolk's desperate efforts to heal the rift. In December 1546, he was arrested in company with his son Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, and charged with treason. Henry VIII died the day before the execution was due to take place, and Norfolk's sentence was commuted to imprisonment. His son was less fortunate and had been executed a few days previously.

Norfolk remained in the Tower throughout the reign of Edward VI of England, and his dukedom remained forfeit, but he was released by Mary I in 1553, the Howards being an important Catholic family, and the dukedom was restored. The Duke showed his gratitude by leading the forces sent to put down the rebellion of Sir Thomas Wyatt, who had protested against the Queen's forthcoming marriage to a Spanish prince, Philip II and had planned to put Anne Boleyn's daughter, the future Elizabeth I on the throne in Mary's place. The result of Norfolk's suppression of the Wyatt Rebellion was Princess Elizabeth's imprisonment in the Tower (although there was not enough evidence to convict her on treason, since she clearly had not been party to the rebels' precise intentions) and the execution of the Queen's cousin Lady Jane Grey. Norfolk, himself, died not long after the Wyatt Rebellion. He was succeeded by his grandson, Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk. The 4th Duke, also a Catholic, was executed on Elizabeth's orders for illegally plotting to marry Mary Queen of Scots.

In 1538, he claimed the titles of Duke of Guelders and Count of Zutphen upon the death of Charles of Egmond, but was unable to gain possession of them.

Antoine was a skilled supporter of the Counter reformation. During his rule, he squelched several popular revolts.

He was born in Hunsdon, Hertfordshire, England, the eldest son of Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, and his second wife, Lady Elizabeth Stafford (daughter of Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham), so he was descended from kings on both sides of his family tree. He was reared at Windsor with Henry VIII's illegitimate son Henry Fitzroy Duke of Richmond, and they became close friends and, later, brothers-in-law. He became Earl of Surrey in 1524 when his grandfather died and his father became Duke of Norfolk.

In 1532 he accompanied his first cousin Anne Boleyn, the King, and the Duke of Richmond to France, staying there for more than a year as a member of the entourage of Francis I of France. In 1536 his first son, Thomas (later 4th Duke of Norfolk), was born, Anne Boleyn was executed on charges of treason, and Henry Fitzroy died at the age of 17 and was buried at one of the Howard homes, Thetford Abbey. That was also the year Henry - who took after his father and grandfather in military prowess - served with his father against the Pilgrimage of Grace Rebellion protesting the dissolution of the monasteries.

He was imprisoned with his father by Henry VIII, who, consumed by his own paranoia, was convinced that Henry Howard had planned to usurp the crown from his son Edward. He was executed for treason on 19 January 1547 sentenced on 13 January 1547 (his father was only saved from execution by it being set for the day after Henry happened to die) his son Thomas became heir to the Dukedom of Norfolk instead, inheriting it on the 3rd Duke's death in 1554.

He is buried in a spectacular painted alabaster tomb at St Michael the Archangel, Framlingham.

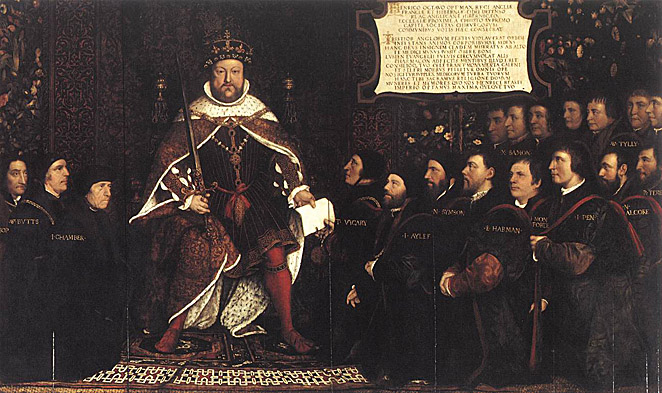

The details of Butts's early life are unclear; he may have been born in either the London borough of Fulham or in Norfolk.

Butts died in 1545, and he is buried at All Saints Church, Fulham, London.

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.