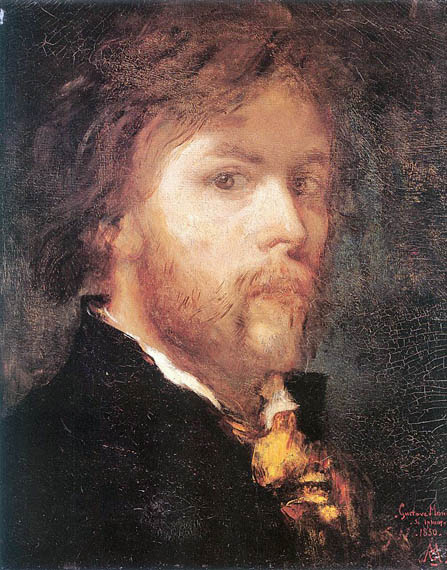

French Symbolist Painter, Sculptor & Watercolorist

1826 - 1898

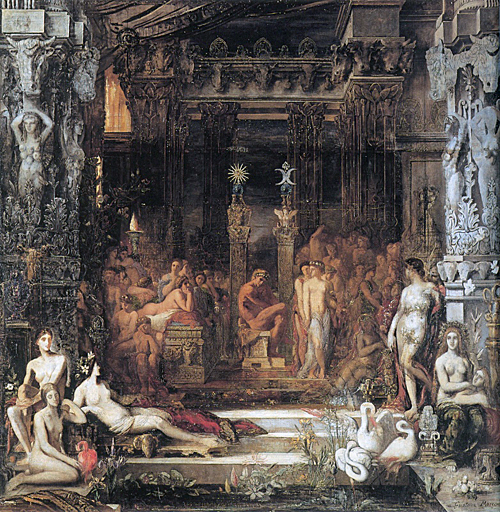

Moreau's main focus was the illustration of biblical and mythological figures. As a painter of literary ideas rather than visual images, he appealed to the imaginations of some Symbolist writers and artists, who saw him as a precursor to their movement.

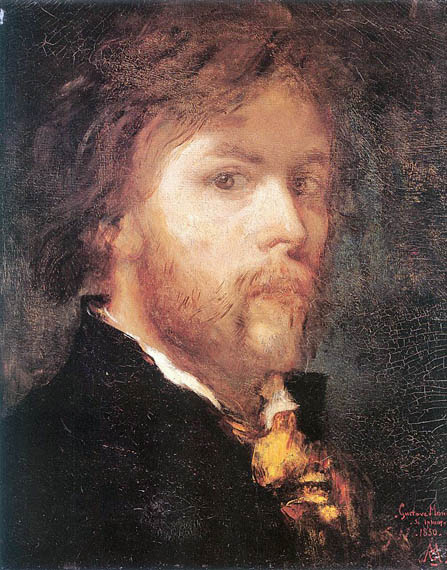

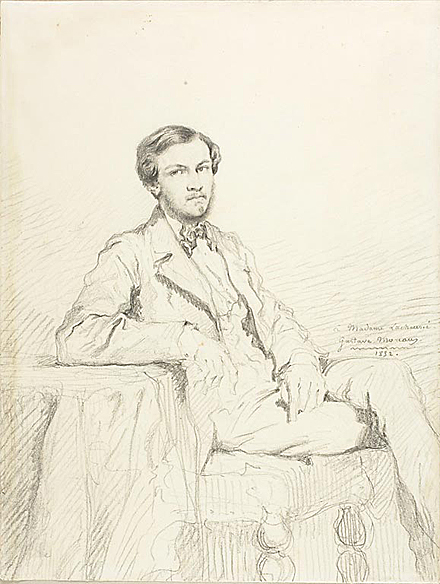

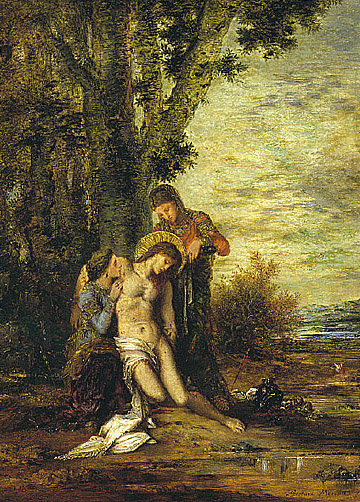

His father, Louis Jean Marie Moreau, was an architect, who recognized his talent. His mother was Adele Pauline des Moutiers. Moreau studied under François-Édouard Picot and became a friend of Théodore Chassériau, whose work strongly influenced his own. Moreau carried on a deeply personal 25-year relationship, possibly romantic, with Adelaide-Alexandrine Dureux, a woman whom he drew several times. His first painting was a Pietà which is now located in the Cathedral at Angoulême. He showed 'A Scene from the Song of Songs' and 'The Death of Darius' in the Salon of 1853. In 1853 he contributed Athenians with the 'Minotaur' and 'Moses Putting Off his Sandals within Sight of the Promised Land' to the Great Exhibition.

'Oedipus and the Sphinx', one of his first symbolist paintings, was exhibited at the Salon of 1864. Over his lifetime, he produced over 8,000 paintings, watercolors and drawings, many of which are on display in Paris' Musée national Gustave Moreau at 14, rue de la Rochefoucauld. The museum is in his former workshop, and was opened to the public in 1903. André Breton famously used to "haunt" the museum and regarded Moreau as a precursor to Surrealism.

He had become a professor at Paris' École des Beaux-Arts in 1891 and counted among his many students the fauvist painters, Henri Matisse and Georges Rouault. Moreau is buried in Paris' Cimetière de Montmartre.

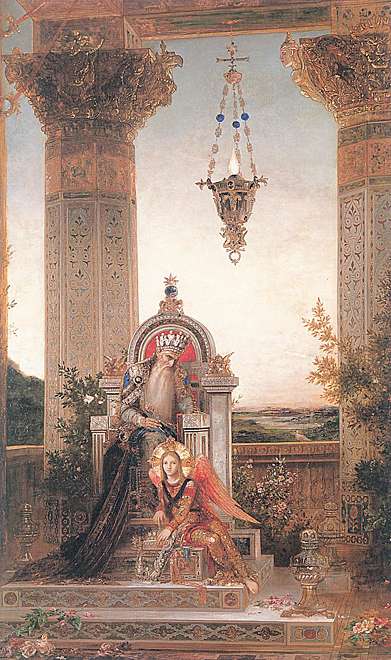

The story of David's seduction of Bathsheba is omitted in Chronicles. The king, while walking on the roof of his house, saw Bathsheba, who was the wife of Uriah the Hittite, taking a bath. He immediately desired her. David then committed adultery with her and she conceived.

In an effort to cover up his sin, David summoned Uriah from the army (with whom he was on campaign) in the hopes that Uriah would sleep with Bathsheba, and thus the child could be passed off as his. However, Uriah was unwilling to violate the ancient kingdom rule applying to warriors in active service. Rather than go home to his own bed, he preferred to remain with the palace troops.

After repeated efforts to get Uriah to lie with Bathsheba, the king gave the order to his general, Joab, that Uriah should be abandoned during a heated battle, and left to the hands of the enemy. Ironically, David had Uriah himself unknowingly carry the message that ordered his death. After Uriah was gone, David made the now widowed Bathsheba his wife.

According to the account in Samuel, David's action was displeasing to the Lord, who accordingly sent Nathan the prophet to reprove the king.

After relating the parable of the rich man who took away the one little ewe lamb of his poor neighbor (II Samuel 12:1-6), and exciting the king's anger against the unrighteous act, the prophet applied the case directly to David's action with regard to Bathsheba.

The king at once confessed his sin and expressed sincere repentance. Bathsheba's child by David was smitten with a severe illness and died at a few days old, which the king accepted as his punishment.

However, Nathan also noted that David's house would be cursed with turmoil because of this murder. This came to pass years later when one of David's much-loved sons, Absalom, led an insurrection that plunged the kingdom into civil war. Moreover, to manifest his claim to be the new King, Absalom had sex in public with ten of his father's concubines - which could be considered a direct, tenfold Divine retribution for David's taking away the woman of another man.

In David's old age Bathsheba secures the succession of her son Solomon instead of David's eldest surviving son, Adonijah.

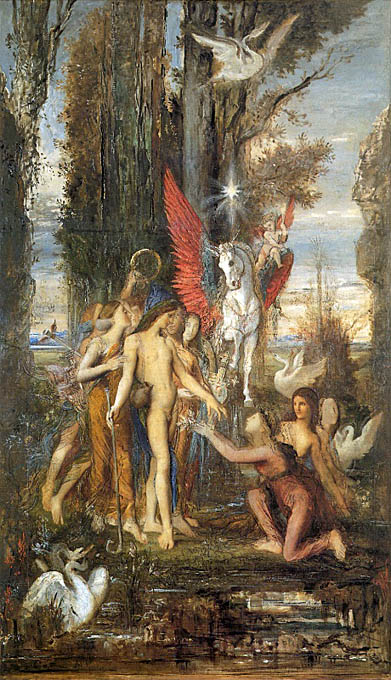

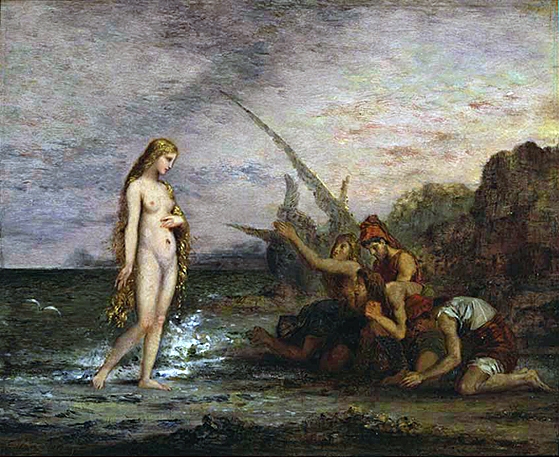

Here, far from illustrating the story, Moreau has gone no further than the first line: "Here is a terrible giant who loves a beautiful nymph". He gives a personal, modern, magical interpretation of the pagan myth, rejecting the anecdotal and concentrating on the opposition between exquisite beauty and hideous ugliness, beauty and the beast, love and disdain. His composition stages a struggle between shadow and light, mineral and liquid, good and evil. Moreau's Polyphemus is nevertheless not an ogre, but a melancholy being, lost in one-eyed contemplation of the inaccessible woman. Galatea, who has taken refuge in a cave too narrow for the giant to enter, is a pearl gleaming in its setting. The change in scale between the two figures is repeated between Galatea and the tiny Nereids almost invisible in the lacework of aquatic plants and coral… This vegetation looks supernatural but was derived from drawings meticulously copied from a book of marine botany in the Museum d'Histoire Naturelle, where Moreau had registered as an unofficial student in 1879. The rubbed, scratched texture of the oil paint gives the work a precious, enameled look. The Salon of 1880 was the last in which Moreau took part. Galatea was a triumph there and marked the height of his career.

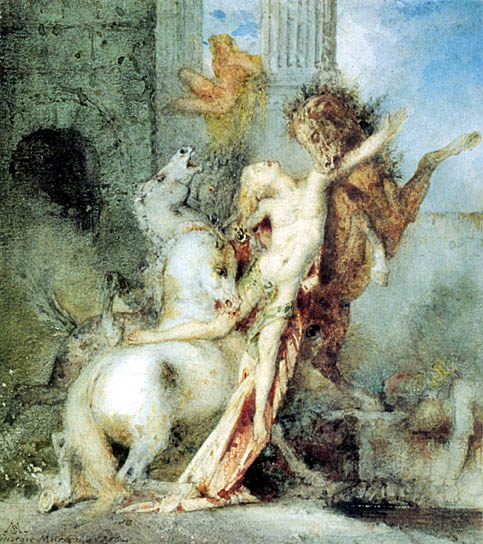

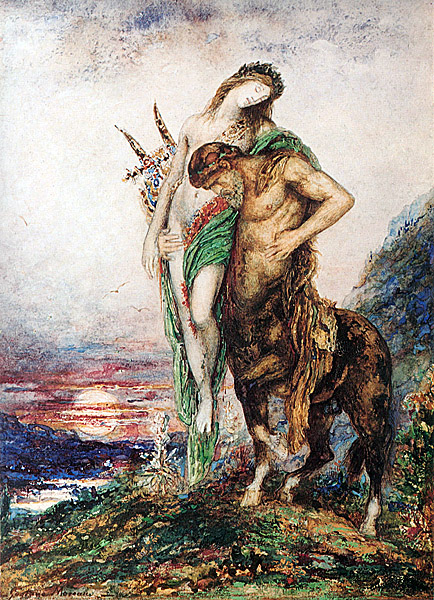

The details of the confrontation are explicit in Apollodorus : realizing that he could not defeat the Hydra in this way, Hercules called on his nephew Iolaus for help. His nephew then came upon the idea (possibly inspired by Athena) of using a burning firebrand to scorch the neck stumps after decapitation, and handed him the blazing brand. Hercules cut off each head and Iolaus burned the open stump leaving the Hydra dead; its one immortal head Hercules placed under a great rock on the sacred way between Lerna and Elaius, and dipped his arrows in the Hydra's poisonous blood, and so his second task was complete. The alternative to this is that after cutting off one head he dipped his sword in it and used its venom to burn each head so it couldn't grow back.

Hercules later used an arrow dipped in the Hydra's poisonous blood to kill the centaur Nessus; and Nessus's tainted blood was applied to the Tunic of Nessus, by which the centaur had his posthumous revenge. Both Strabo and Pausanias report that the stench of the river Anigrus in Elis, making all the fish of the river inedible, was reputed to be due to the Hydra's poison, washed from the arrows Hercules used on the centaur.

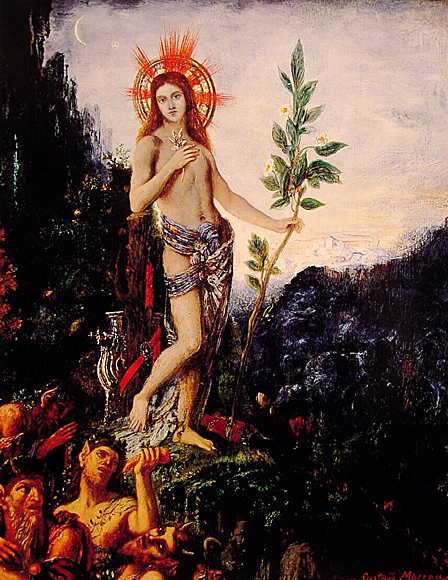

In Works and Days Hesiod divided time into five ages:--the Golden age, ruled by Cronos, when people lived extremely long lives 'without sorrow of heart'; the Silver age, ruled by Zeus; the Bronze age, an epoch of war; the Heroic age, the time of the Trojan war; and lastly the Iron age, the corrupt present. This is similar to Hindu and Buddhist concepts of the Kali Yuga. The idea of a Golden Age has likewise had a profound impact on western thought. Works and Days also discusses pagan ethics, extols hard work, and lists lucky and unlucky days of the month for various activities.

The Theogony presents the descent of the gods, and, along with the works of Homer, is one of the key source documents for Greek mythology; it is the Genesis of Greek mythology. It gives the clearest presentation of the Greek pagan creation myth, starting with the creatrix goddesses Chaos and Earth, from whom descended all the gods and men; it mentions hundreds of individual gods, goddesses, demi-gods, elementals and heroes.

And gradually she lost her fear, and he

Offered his breast for her virgin caresses,

His horns for her to wind with chains of flowers

Until the princess dared to mount his back

Her pet bull's back, unwitting whom she rode.

Then - slowly, slowly down the broad, dry beach

First in the shallow waves the great god set

His spurious hooves, then sauntered further out

'til in the open sea he bore his prize

Fear filled her heart as, gazing back, she saw

The fast receding sands. Her right hand grasped

A horn, the other lent upon his back

Her fluttering tunic floated in the breeze.

His picturesque details belong to anecdote and fable: in all the depictions, whether she straddles the bull, as in archaic vase-paintings or the ruined metope fragment from Sikyon, or sits gracefully sidesaddle as in a mosaic from North Africa, there is no trace of fear. Often Europa steadies herself by touching one of the bull's horns, acquiescing.

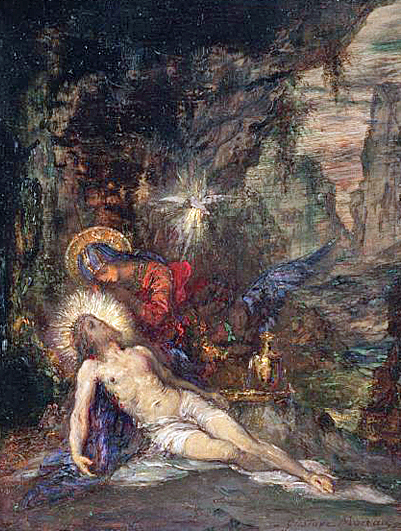

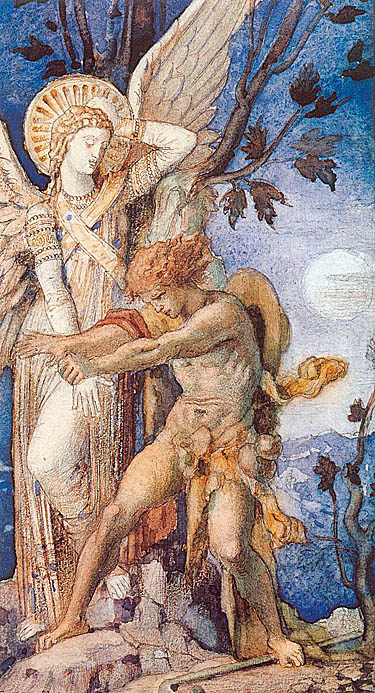

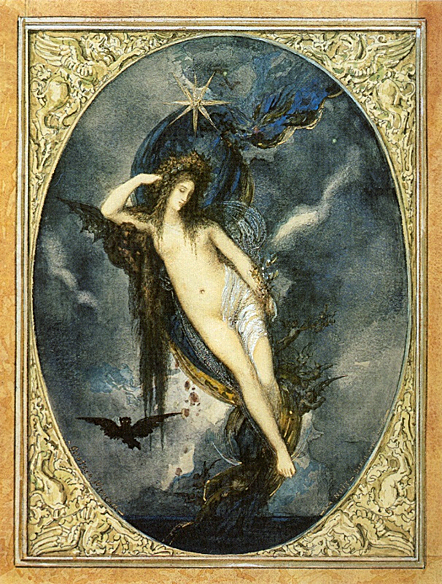

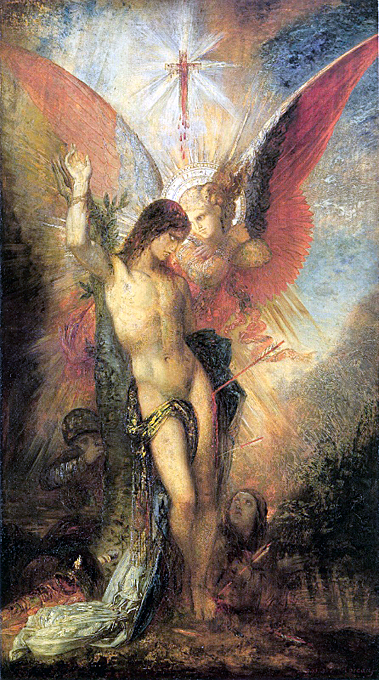

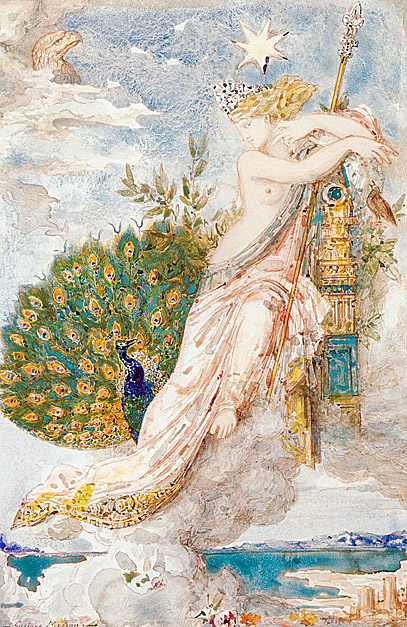

In his last years, Moreau worked on enormous, very detailed compositions in oil, most of which were never finished. Watercolors were prominent in Moreau's lat work, as he was able to create small and jewel-like visions with a detail and brilliance that eluded him in the larger oils. Color, which appears as light shot through crushed gems, is the true subject of this dreamlike composition of a poet receiving inspiration from a winged muse.

_1865.jpg)

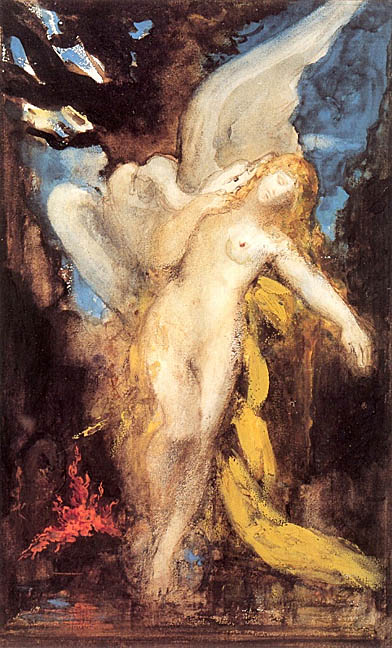

A sudden blow: the great wings beating still

Above the staggering girl, her thighs caressed

By the dark webs, her nape caught in his bill,

He holds her helpless breast upon his breast.

How can those terrified vague fingers push

The feathered glory from her loosening thighs?

And how can body, laid in that white rush,

But feel the strange heart beating where it lies?

A shudder in the loins engenders there

The broken wall, the burning roof and tower

And Agamemnon dead.

Being so caught up,

So mastered by the brute blood of the air,

Did she put on his knowledge with his power

Before the indifferent beak could let her drop?

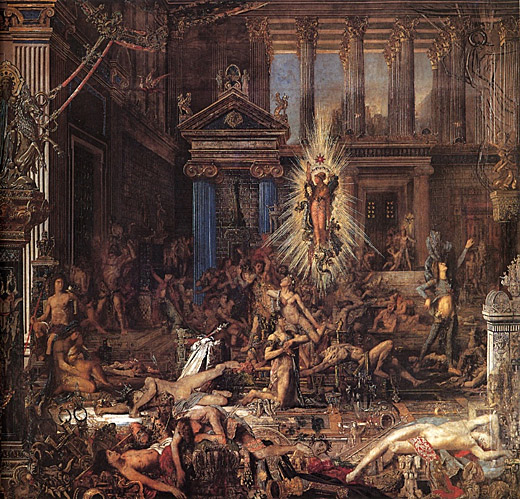

Either in 37 or 38, Messalina married her second cousin Claudius who was about 48 years old. During the reign of another second cousin of hers, the unstable Roman Emperor Caligula (reigned 37-41), Messalina was very wealthy, an influential figure and a regular at Caligula's court. Claudius was Caligula's paternal uncle and was becoming influential and popular. Claudius probably married her to strengthen ties within the imperial family.

Messalina bore Claudius two children, a daughter Claudia Octavia (born 39 or 40), who was a future empress and first wife to future emperor Nero, and a son, Britannicus (born 41). On 24 January 41, Caligula and his family were murdered and later that day the Praetorian Guard proclaimed Claudius the new emperor and Messalina became the new empress.

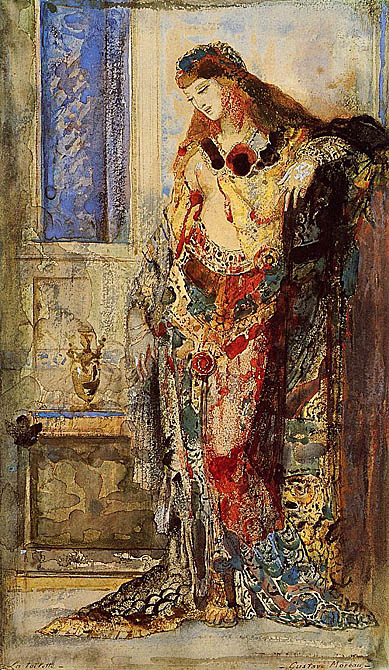

The ancient Roman sources (particularly Tacitus and Suetonius), portray Messalina as insulting, disgraceful, cruel, avaricious, and a foolish nymphomaniac. Many women of her age and status enjoyed festivities and parties, but the two historians contended that Messalina unwisely combined her zest for meeting people with a sexual appetite.

The oft-repeated tale of Messalina's all-night sex competition with a prostitute comes from Book X of Pliny's Naturalis Historia. Pliny does not name the prostitute; the Restoration playwright Nathaniel Richards calls her Scylla in The Tragedy of Messalina, Empress of Rome, published in 1640, and Robert Graves in his novel Claudius the God also identified the prostitute as Scylla. According to Pliny, the competition lasted for 24 hours and Messalina won with a score of 25 partners.

Roman sources claim that Messalina used sex to enforce her power and control politicians, that she had a brothel under an assumed name and organized orgies for upper class women and that she participated much in politics and sold her influence to Roman nobles or foreign notables.

Juvenal is also highly critical of her in his Satire VI :

Then consider the God's rivals, hear what Claudius

had to put up with. The minute she heard him snoring

his wife - that whore-empress - who dared to prefer the mattress

of a stews to her couch in the Palace, called for her hooded

night-cloak and hastened forth, with a single attendant.

Then, her black hair hidden under an ash-blonde wig,

she'd make straight for her brothel, with its stale, warm coverlets,

and her empty reserved cell. Here, naked, with gilded

nipples, she plied her trade, under the name of 'The Wolf-Girl',

parading the belly that once housed a prince of the blood.

She would greet each client sweetly, demand cash payment,

and absorb all their battering - without ever getting up.

Too soon the brothel-keeper dismissed his girls:

she stayed right till the end, always last to go,

then trailed away sadly, still | with burning, rigid vulva,

exhausted by men, yet a long way from satisfied,

cheeks grimed with lamp-smoke, filthy, carrying home

to her Imperial couch the stink of the whorehouse.

During the Secular Games in 47, at the performance of the Troy Pageant, Messalina attended the event with her son Britannicus. Also present was Agrippina the Younger with her son Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus (Nero). Agrippina and Nero received a greater acclamation from the audience than Messalina and Britannicus did. Many people began to show pity and sympathy to Agrippina, due to unfortunate circumstances that occurred in her life. This is probably a first sign of Messalina's declining popularity.

Later that year, Messalina became interested in the attractive Roman Senator Gaius Silius who was happily married to the aristocratic woman Junia Silana (sister of Caligula's first wife). Messalina and Silius became lovers and Messalina forced Silius to divorce his wife.

Silius realized the danger that he put himself in. Messalina and Silius plotted to kill the weak emperor and Messalina would make him the new emperor. Silius was childless and wanted to adopt Britannicus. They had committed bigamy: Messalina and Silius married in a full ceremony, in front of witnesses and had signed marriage contracts while Messalina was still legally married to Claudius.

While Claudius was in Ostia, inspecting construction work done on the harbor, his freedman Narcissus, advised him of Messalina's and Silius' plot to kill him. Messalina travelled to Ostia with her children hoping to speak to Claudius; however the emperor left Ostia before she was able to do so. Narcissus delayed Messalina, preventing her from seeing Claudius.

Claudius ordered the deaths of Messalina and Silius in 48. In Messalina's final hours, she was in the Gardens of Lucullus. Messalina and her mother were preparing a petition for Claudius. At the height of Messalina's influence and prosperity, Lepida and Messalina had argued and became estranged. Apparently overcome by pity, Lepida stayed with her daughter. Lepida's last words to her were 'Your life is finished. All that remains is to make a decent end'. Messalina was reputedly weeping and moaning. She finally realized the situation in which she had put herself.

An officer and a former slave arrived together to witness Messalina's death. The former slave verbally insulted her while the officer stood by in silence. Messalina was offered the choice of killing herself, but was too afraid to do so, so the officer stabbed Messalina with a dagger. Her dead body was left with her mother. At the time of Messalina's death, Claudius was attending a dinner. When Messalina's death was announced to him, Claudius showed no emotion but asked for more wine.

In the days after her death, Claudius gave no sign of hatred, anger, distress, satisfaction or any other human passion. The only ones who mourned for Messalina were her children. The Roman Senate ordered Messalina's name removed from all public or private places and all statues of her were removed.

On New Year's Day in 49, Claudius married as his fourth wife Agrippina the Younger, who went on to remove from the imperial court anyone she considered loyal to the memory of Messalina. Agrippina's son Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus was adopted by Claudius as his son and heir. He became known as Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus Germanicus and succeeded Claudius as emperor instead of Messalina's son Britannicus. Nero married Messalina's daughter. Messalina's name is now often used as a synonym for sexual promiscuity, manipulation, and treachery.

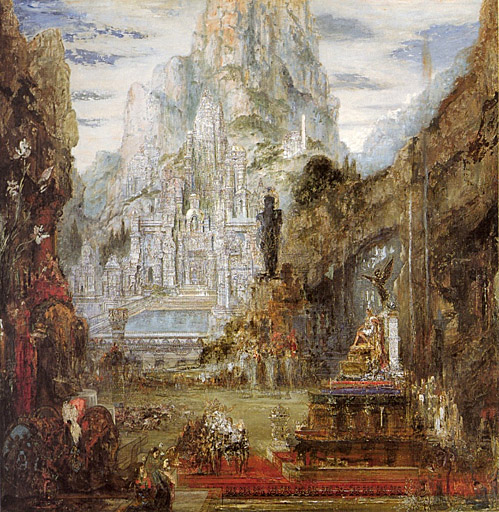

Saint George is one of the most venerated saints in the Anglican Church, Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodox Churches, and the Eastern Catholic Churches. He is immortalized in the tale of George and the Dragon and is one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers. His memorial is celebrated on 23 April.

Saint George is the patron saint of Aragon, Catalonia, England, Ethiopia, Georgia, Greece, Palestine, Portugal, and Russia, as well as the cities of Amersfoort, Beirut, Bteghrine, Cáceres, Ferrara, Freiburg, Genoa, Ljubljana, Lod and Moscow, as well as a wide range of professions, organizations and disease sufferers.

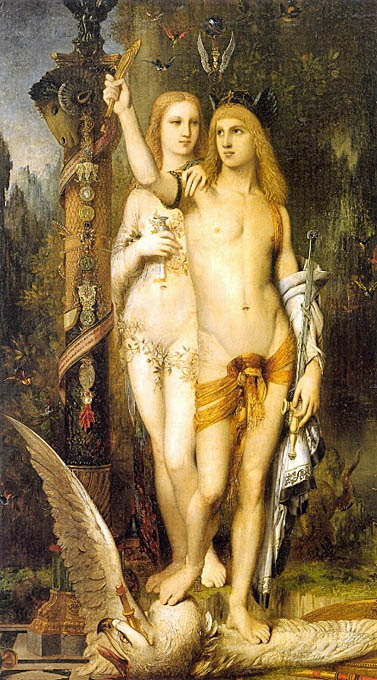

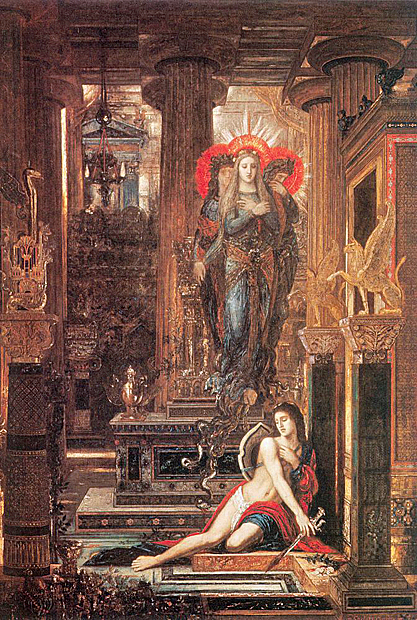

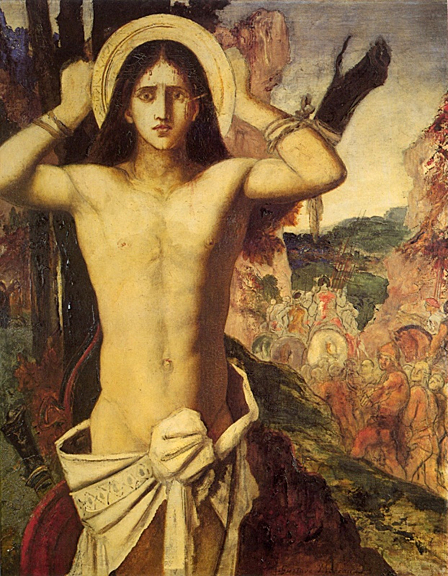

The haloed figure of the saint recalls works of the early Renaissance that Moreau would have seen in Italy, notably those of Carpaccio and Crivelli. The figure of the princess with her hands folded in prayer in the right background, and the visionary Gothic castle in the distance, have been compared to those seen in eastern miniatures.

Much later, Hemera (day), who is now Night's sister rather than daughter, leaves Tartarus (the underworld) just as Nyx entered it; when Hemera returns, Nyx leaves.

Reread the list of characteristics associated with Nyx's offspring and I'm sure you'll understand why, throughout history, we have feared the night. But night-time in the big city can be fun - and bright - and noisy. We're more likely to party. We may still fear a dark alley, but for the most part, Nyx has lost some of her power over us. In fact, she may now be the one bothered by us - unable to sleep - kept awake by endless activity and traffic. Well, at least she can thank Asclepius, the demigod of medicine, for her sleeping pills.

A narrow escape from a creature half monster, half angel - psychosis

THE ERINYES were three netherworld goddesses who avenged crimes against the natural order. They were particularly concerned with homicide, un-filial conduct, crimes against the gods, and perjury. A victim seeking justice could call down the curse of the Erinys upon the criminal. The most powerful of these was the curse of the parent upon the child--for the Erinyes were born of just such a crime, being sprung from the blood of Ouranos, when he was castrated by his son Kronos.

The wrath of the Erinyes manifested itself in a number of ways. The most severe of these was the tormenting madness inflicted upon a patricide or matricide. Murderers might suffer illness or disease; and a nation harboring such a criminal, could suffer death, and with it hunger and disease. The wrath of the Erinyes could only be placated with the rite ritual purification and the completion of some task assigned for atonement.

The goddesses were also servants of Hades and Persephone in the underworld where they oversaw the torture of criminals consigned to the Dungeons of the Damned.

The Erinyes were similar to if not the same as the Poinai (Retaliations), Arai (Curses), Praxidikai (Exacters of Justice) and Maniai (Madnesses).

They were depicted as ugly, winged women with hair, arms and waists entwined with poisonous serpents. They wielded whips and were clothed either in the long black robes of mourners, or the short-length skirts and boots of huntress- maidens.

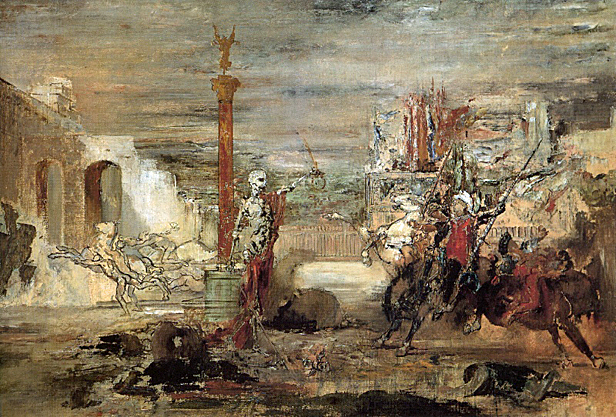

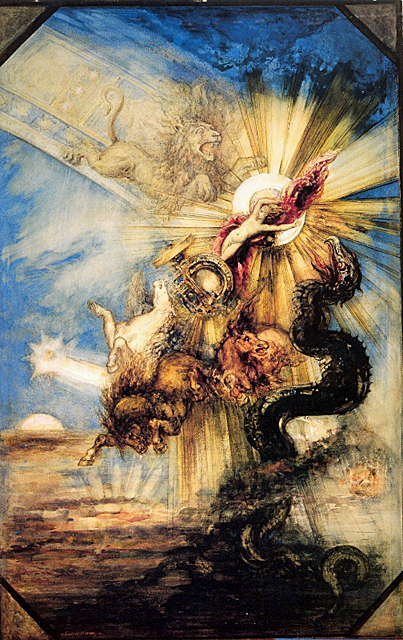

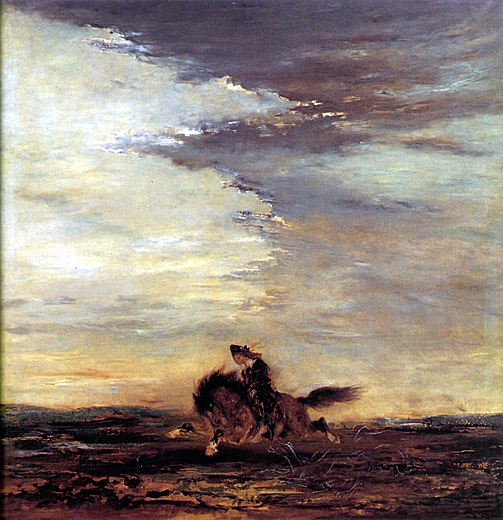

Once in the chariot, Phaeton quickly lost control of the mighty horses, and he was soon flying crazily in the sky. The damage caused by the chariot of the sun was devastating. Zeus, ruler of the Greek gods, took immediate steps to stop the carnage, and cast a thunderbolt at the boy.

This is the moment captured in Moreau's painting. The form of Phaeton is a great diagonal gash in the image, as his body falls from the sky. A nimbus of light surrounds Phaeton, indicating the rays of the sun. The chariot plummets as well, with the horses panicking, their legs pawing at the air. Gustave Moreau's Phaeton is a very effective treatment of this myth. It is dramatic and dynamic, and it is also one of the artist's more active paintings.

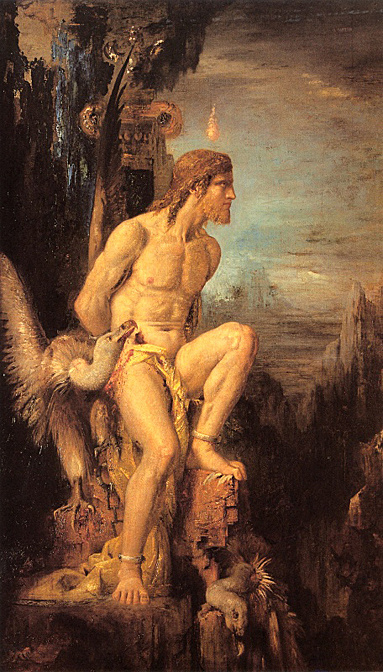

The next stage in Prometheus' career as benefactor of mankind came when Zeus and he were developing the ceremonial forms for animal sacrifice. The astute Prometheus devised a sure-fire way to help man. He divided the slaughtered animal parts into two packets. In one was the ox-meat and innards wrapped up in the stomach lining. In the other packet were the ox-bones wrapped up in its own rich fat. One would go to the gods and the other to the humans making the sacrifice. Prometheus presented Zeus with a choice between the two, and Zeus took the deceptively richer appearing: the fat-encased, but inedible bones.

Next time someone says "don't judge a book by its cover," you may find your mind wandering to this cautionary tale.

As a result of Prometheus' trick, for ever after, whenever man sacrificed to the gods, he would be able to feast on the meat, so long as he burned the bones as an offering for the gods.

Zeus reacted to these tricks by presenting man with a "gift," Pandora, the first woman. While Prometheus may have crafted man, woman was a different sort of creature. She came from the forge of Hephaestus, beautiful as a goddess and beguiling. Zeus presented her as a bride to Prometheus' brother Epimetheus. Prometheus had the gift of thinking ahead, but Epimetheus was only capable of afterthought, so Prometheus, expecting retribution for his audacity, had warned his brother against accepting gifts from Zeus.

Zeus gave the gods-crafted Pandora as bride to Epimetheus, along with a box that they were instructed to keep closed. Epimetheus was dazzled by Pandora and forgot the advice of his prescient brother.

Prometheus was still not awed by the might of Zeus and continued to defy him, refusing to warn him of the dangers of the nymph Thetis (future mother of Achilles). Zeus had tried punishing Prometheus through his loved ones, but this time he decided to punish him more directly. He ordered Hephaestus (or Hermes) to chain Prometheus to Mount Caucasus where an eagle/vulture ate his ever-regenerating liver each day. This is the topic of Aeschylus' tragedy Prometheus Bound and many paintings.

Eventually Hercules rescued Prometheus, and Zeus and the Titan were reconciled.

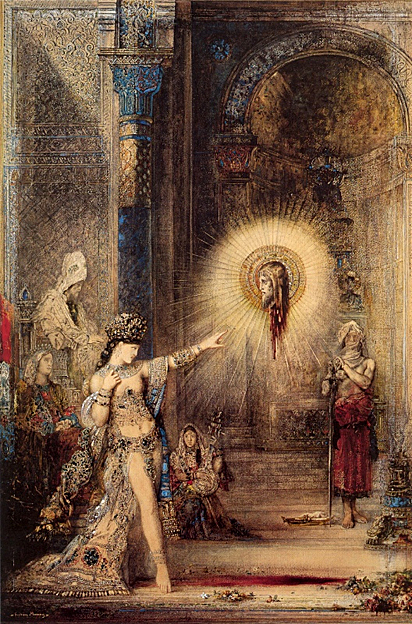

Herod is in love with his own daughter "bizarre I know" but of course, she does not love him in that fashion. Salome in order to force her papa to get John's head she danced in order to "seduce" him, Hence, Salome dances for Herod.

In this watercolor, Gustave Moreau reveals his ability to capture a moment of intense emotion. The artist has depicted Sappho languishing on an isolated cliff, her classically inspired features frozen in an expression of utter despair. The tip of a stylized musical instrument can be glimpsed behind the poet, which reinforces her connection to poetry and music.

Moreau was a master of depicting melancholy in his paintings, as this watercolor demonstrates. In addition, it is worth noting that the artist was haunted by the story of Sappho. He revisited the motif of the melancholy poet many times during his artistic career, in watercolor, pencil drawings, sketches, and oil paintings.

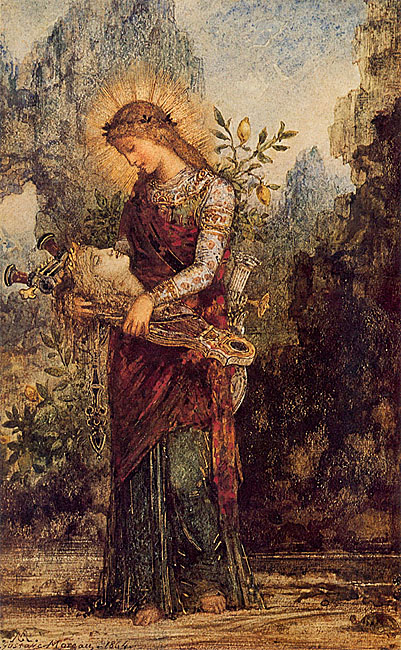

Is Moreau illustrating the end of Salome's dance in this watercolor? The head would then appear to her as the image of her terrifying wish. Or is it a scene after the beheading, an image of remorse? For Huysmans the "murder had been committed". Salome remains a femme fatale, even when filled with horror, in a long description he wrote about the work in chapter five of Against Nature (1884). According to other critics, it was the painter's consumption of opium which produced hallucinations like this. Although unfounded, this accusation has persisted over many years.

As he often did, Moreau has used several motifs for his composition. The head of John the Baptist, with its halo, recalls a Japanese print copied by Moreau at the Palais de l'Industrie in 1869. It is also reminiscent of the famous head of Medusa, brandished by Perseus, in Benvenuto Cellini's bronze in Florence (Loggia dei Lanzi). As for the decoration of Herod's palace, it is directly inspired by the Alhambra in Granada.

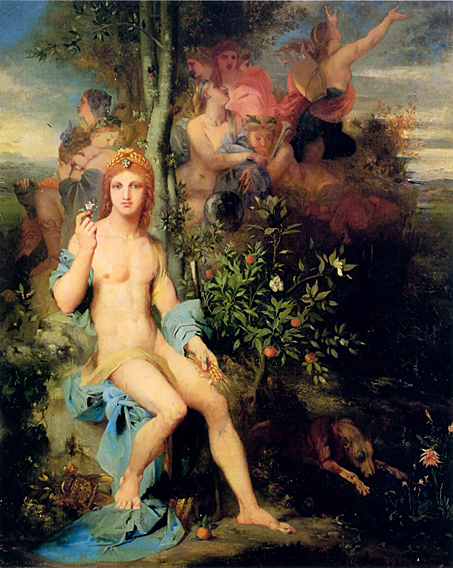

Just as Dubufe forestalled the Salon of 1863 with his Venus, so too must Moreau have been affected by his contemporaries' successes with the subject. The Salon of 1863, contained three Venuses of particular note: Amaury-Duval's standing figure, described by the critic Castagnary as 'traditional…no new accent, no new feeling,' Alexander Cabanel's writhing, horizontal figure who covers her face in a hollow act of modesty, and in a less direct reference, Manet's Olympia, a canvas that ferociously referenced Titian's great Venus of Urbino. It was arguably Manet's painting that became the next chapter in a discussion of the nude as an iconographic representation of Love in its many forms.

In this version for Hayem the format is more elongated. The young man, whose legs had been criticized in 1865 for being too short, is slimmer. Moreau portrays a "calm and peaceful scene". The young artist at the entrance to the underworld wears a crown of laurels from Apollo. He is followed, not by a skeleton or an old man signifying Time, as Gustave Moreau had originally envisaged, but by a delicate figure. However, it is still Death "sleeping in her eternal indifference", carrying the sword and the hourglass". She floats, on a diagonal, her feet not touching the ground, like a ghost.

In a letter to Fécamp on 15 July 1883, the poet Jean Lorrain confided to Moreau: "I am absolutely haunted by the Hayem watercolors and paintings; the last two Thursdays in his gallery have been the two most exquisite hours of my stay in Paris". The same day he sent a handwritten sonnet "The young man and death" which was published in 1897 in the magazine L'Ombre Ardente. In it, he praises "this dazzling Adonis" who "lightly steps down the three mystical steps".

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.