Italian Rococo Painter and Etcher

1697 - 1768

Giovanni Antonio Canal better known as Canaletto, was a Venetian painter famous for his landscapes, or vedute, of Venice. He was also an important printmaker in etching.

He was born in Venice as the son of the painter Bernardo Canal, hence his pseudonym Canaletto ("little Canal"), and Artemisia Barbieri. His nephew and pupil Bernardo Bellotto was also an accomplished landscape painter, with a similar painting style, and sometimes used the name "Canaletto" to advance his own career, particularly in countries-Germany and Poland-where his uncle was not active.

Canaletto served his apprenticeship with his father and his brother. He began in his father's occupation, that of a theatrical scene painter. Canaletto was inspired by the Roman vedutista Giovanni Paolo Pannini, and started painting the daily life of the city and its people.

After returning from Rome in 1719, he began painting in his famous topographical style. His first known signed and dated work is 'Architectural Capriccio' 1723. Studying with the older Luca Carlevaris, a moderately-talented painter of urban cityscapes, he rapidly became his master's equal.

In 1725, the painter Alessandro Marchesini, who was also the buyer for the Lucchese art collector Stefano Conti had inquired about buying two more 'Views of Venice', when the agent informed him to consider instead the work of "Antonio Canale... it is like Carlevaris, but you can see the sun shining in it."

Much of Canaletto's early artwork was painted 'from nature', differing from the then customary practice of completing paintings in the studio. Some of his later works do revert to this custom, as suggested by the tendency of distant figures to be painted as blobs of color - an effect produced by using a camera obscura, which blurs farther-away objects.

However, his paintings are always notable for their accuracy: he recorded the seasonal submerging of Venice in water and ice.

Canaletto's early works remain his most coveted and, according to many authorities, his best. One of his finest early pieces is 'The Stonemason's Yard' 1729 which depicts a humble working area of the city.

Although we associate Canaletto for the most part with mass-produced, crystal-clear scenes of celebrated sights, the 'Stonemason's Yard', his masterpiece, is not of this kind. A comparatively early picture, and almost certainly made to order for a Venetian client, it presents an intimate view of the city, as if from a rear window. The site is not in fact a mason's yard, but the Campo San Vidal during re-building operations on the adjoining church of San Vidal or Vitale. Santa Maria della Carita, now the Accademia di Belle Arti, the main art gallery in Venice, is the church seen across the Grand Canal. The Church of Santa Maria della Carita is still flanked by the slender campanile that collapsed in 1741.

Canaletto's later works are painted rather tightly on a reflective white ground, but this picture was freely brushed over reddish brown, the technical reason for the warm tonality of the whole. Thundery clouds are gradually clearing, and the sun casts powerful shadows, whose steep diagonals help define the space and articulate the architecture. Not doges and dignitaries but the working people and children of Venice animate the scene and set the scale. In the left foreground a mother has propped up her broom to rush to the aid of her fallen and incontinent toddler, watched by a woman airing the bedding out of the window above and a serious little girl. Stonemasons kneel to their work. A woman sits spinning at her window. The city, weather-beaten, dilapidated, lives on, and below the high bell-tower of Santa Maria della Carita it is the little shabby house, with a brave red cloth hanging from the window, which catches the brightest of the sunlight.

The Campo San Vidal is in the foreground which is cluttered with pieces of Istrian stone, and blocked by a workman's hut - all evidence of the stonemasons' toil for the nearby, although unseen, church of San Vidal. Potted plants are carefully placed on balconies, washing is strung between buildings, wisps of smoke emerge from a chimney, and the tools of the workmen are all carefully denned.

All of this anecdote and informality is contained within a composition of lucid and almost monumental structure. It is, though, by no means too rigidly imposed; variation is provided by the slanting shadows and rhythm of the skyline, as well as the constantly shifting textures and hues of the buildings - crumbling russet plaster, dark brick and honeyed timber.

Later Canaletto became known for his grand scenes of the canals of Venice and the Doge's Palace. His large-scale landscapes portrayed the city's famed pageantry and waning traditions, making innovative use of atmospheric effects and strong local colors. For these qualities, his works may be said to have anticipated Impressionism.

Many of his pictures were sold to Englishmen on their Grand Tour, often through the agency of the merchant Joseph Smith (who was later appointed British Consul in Venice in 1744).

It was Smith who acted as an agent for Canaletto, first in requesting paintings of Venice from the painter in the early 1720's and helping him to sell his paintings to other Englishmen.

In the 1740's Canaletto's market was disrupted when the War of the Austrian Succession led to a reduction in the number of British visitors to Venice. Smith also arranged for the publication of a series of etchings of caprichios (or architectural fantasies) (capriccio Italian for fancy) in his vedute ideale, but the returns were not high enough, and in 1746 Canaletto moved to London, to be closer to his market.

He remained in England until 1755, producing views of London (including the 'New Westminster Bridge') and of his patrons' castles and houses. His 1754 painting of 'Old Walton Bridge' includes an image of Canaletto himself.

He was often expected to paint England in the fashion with which he had painted his native city. Overall this period was not satisfactory, owing mostly to the declining quality of Canaletto's work. Canaletto's painting began to suffer from repetitiveness, losing its fluidity, and becoming mechanical to the point that the English art critic George Vertue suggested that the man painting under the name 'Canaletto' was an impostor.

The artist was compelled to give public painting demonstrations in order to refute this claim; however, his reputation never fully recovered in his lifetime.

After his return to Venice, Canaletto was elected to the Venetian Academy in 1763. He continued to paint until his death in 1768. In his later years he often worked from old sketches, but he sometimes produced surprising new compositions. He was willing to make subtle alternations to topography for artistic effect.

His pupils included his nephew Bernardo Bellotto, Francesco Guardi, Michele Marieschi, Gabriele Bella, and Giuseppe Moretti (painter). The painter, Giuseppe Bernardino Bison was a follower of his style.

Joseph Smith sold much of his collection to George III, creating the bulk of the large collection of Canaletto's owned by the Royal Collection. There are many examples of his work in other British collections, including several at the Wallace Collection and a set of 24 in the dining room at Woburn Abbey.

Canaletto's views always fetched high prices, and as early as the 18th century Catherine the Great and other European Monarchs vied for his grandest paintings. The record price paid at auction for a Canaletto is 18.6 Pounds million for 'View of the Grand Canal from Palazzo Balbi to the Rialto', set at Sotheby's in London in July 2005.

From: Wikipedia

Giovanni Antonio Canal, Venetian painter, the son of Bernardo Canal, a well-known scenery painter at the time. 'Canaletto' - or small canal - as he was soon called, received his training in the studio of his father and his brother, with whom he continued to collaborate for several years. He became the most famous view-painter of the 18th century.

He began his career as a theatrical scene painter (his father's profession), but he turned to topography during a visit to Rome in 1719-20, when he was influenced by the work of Giovanni Paolo Pannini. In Rome in his own words 'irritated by the immodesty of the playwrights, (he) formally abandoned the theatre,' to devote himself entirely to painting al naturale (from nature). It is not entirely clear what inspired him to this, but it was most likely his acquaintance with the work, and possibly also the person, of Caspar van Wittel.

By 1723 he was painting picturesque views of Venice, marked by strong contrasts of light and shade and free handling, this phase of his work culminating in the splendid Stone Mason's Yard. Meanwhile, partly under the influence of Luca Carlevaris, and largely in rivalry with him, Canaletto began to turn out views which were more topographically accurate, set in a higher key and with smoother, more precise handling - characteristics that mark most of his later work. At the same time he began painting the ceremonial and festival subjects which ultimately formed an important part of his work.

His patrons were chiefly English collectors, for whom he sometimes produced series of views in uniform size. Conspicuous among them was Joseph Smith, a merchant, appointed British Consul in Venice in 1744. It was perhaps at his instance that Canaletto enlarged his repertory in the 1740's to include subjects from the Venetian mainland and from Rome (probably based on drawings made during his visit as a young man), and by producing numerous capricci. He also gave increased attention to the graphic arts, making a remarkable series of etchings, and many drawings in pen, and pen and wash, as independent works of art and not as preparation for paintings. Meanwhile, in his painting there was an increase in an already well-established tendency to become stylized and mechanical in handling. He often used the camera obscura as an aid to composition. In 1746 he went to England, evidently at the suggestion of Jacopo Amigoni (the War of the Austrian Succession drastically curtailed foreign travel, and Canaletto's tourist trade in Venice had dried up).

For a time he was very successful painting views of London and of various country houses. Subsequently, his work became increasingly lifeless and mannered, so much so that rumors were put about, probably by rivals, that he was not in fact the famous Canaletto but an impostor. In 1755 he returned to Venice and continued active for the remainder of his life. Legends of his having amassed a fortune in Venice are disproved by the official inventory of his estate on his death. Before this, Joseph Smith had sold the major part of his paintings to George III, thus bringing into the royal collection an unrivalled group of Canaletto's paintings and drawings. Canaletto was highly influential in Italy and elsewhere. His nephew Bernardo Bellotto took his style to Central Europe and his followers in England included William Marlow and Samuel Scott.

Returning to Venice from Rome, where he was a theatrical scene painter, Canaletto soon received attractive commissions for large, decorative, topographical canvases, although he also continued to paint fantastic landscapes in the then very modern, pre-Romantic style of Marco Ricci. The earliest known 'vedute' by Canaletto's hand is a series of four, probably painted for a local patron to decorate the walls of a central hall of a palazzo. (Now two are in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection, Madrid and two in the Museo del Settecento in Venice).

Unlike other pictures from the same set, it shows a part of the city not found on the itinerary of most visitors. This is an area where Venetians live and work, rather than a well-known site. At the left the footway runs along before the church of San Lazzaro dei Mendicanti and the Scuola di San Marco. A wooden bridge spans the canal, while beyond it can be seen the Ponte del Cavallo. The artist has particularly exploited the colorful laundry hung out from the rooftops and windows at the right. There is a heavy, ponderous atmosphere, achieved through the dappled treatment of the silvery light and feathery brushstrokes. This approach, which in part anticipates the work of the Venetian painter Francesco Guardi (1712-93), is characteristic of Canaletto's earliest pictures.

The exhibited canvas is one of Canaletto's earliest town views, but even in this youthful work his mastery of topography is manifest - all the more so since it involves in this case a most conventional scene, with an uncommonly modest figuration. Like his predecessors, Canaletto chose a central, fairly high point of view, as if the spectator were looking with him through the small hole of a peep-box. However, since the obviously accentuated gutters on the square are parallel to one another whereas the two Procuratie are not, there is a tension to the perspective that breaks the classic peep-box construction. The same can be said of the powerful vertical lines of the Campanile, which fastens, as it were, the entire composition securely on to the upper edge of the canvas. In the best baroque tradition, moreover, Canaletto manipulates the shadows in order to achieve a sense of depth and to arrange the composition, consciously omitting the shadow normally cast by the Campanile at this time of day.

From all this it is clear that Canaletto was trained in stage decoration in the tradition of baroque perspective painting. Nonetheless, the open construction, the loose but powerful handling of the brush and the warm colors make it clear that he was also inspired by the 'natural' stage decoration and paintings of Marco Ricci, which were considered the height of modernity at the time.

The painting is part of a series of four vedute, the earliest known vedute by Canaletto's hand. (Now two are in the Thyssen collection and two in the Museo del Settecento in Venice). Most likely the series was painted for a local patron, to decorate the walls of a portego, or central hall, in a palazzo.

This hypothesis is supported not only by the large size of the four canvases, the broad plan of their compositions and the rather loose brushwork, but also by the combination of the chosen subjects. The identity of the patron is not known.

_1724_25.jpg)

In 1725 Canaletto met two British residents, the art impresario Owen McSwiney and the merchant Joseph Smith. McSwiney invited him to participate in a project to furnish English houses with large, imaginary landscape paintings, and also ordered a number of small topographical paintings on copper, likewise for the English market. McSwiney, however, was soon supplanted as Canaletto's 'manager' by Joseph Smith. Besides small paintings for the market, Smith commissioned a series of six large canvases from the master showing freely conceived, theatrical views of Piazza San Marco and its surroundings intended for his own house, followed by a number of views of the Grand Canal.

In these canvases Canaletto was apparently striving for the greatest verisimilitude, in which he succeeded by virtue of his great ingenuity and artistic sensibility. The curvature of the river is beautifully rendered in an arc flowing from the approaching sloop, under the dark bridge and on to the sunlit area beyond. This movement is effected by the curving roofline on the left and by the gondolas crossing the canal in the foreground, which binds the composition horizontally. As in so many other cases Canaletto was not the first to represent this particular cityscape; there is an early eighteenth-century print of the same subject by Filippo Vasconi which, in turn, is based on an etching by Israel Silvestre from the mid-seventeenth century.

Here, too, Canaletto must have planned his composition with the help of two, now lost, preparatory drawings covering an angle of approximately ninety degrees. The compositional sketch for the painting has survived and in it we can see how the master combined the two views, creating an effect similar to that of a photograph produced by a wide-angle lens.

It can be assumed that Canaletto painted the pendant while sitting on the adjacent terrace. This would mean that the two paintings together span one hundred and eighty degrees, a semi-circle. At the same time, they can stand as entirely independent compositions. In the veduta under discussion, the receding walls on the opposite sides of the canal form, as it were, a narrow pivot, anchored on the white cloud which fans out in all directions; this cloud is the main binding element in the composition. The tower of San Cassiano on the left and the terrace on the right mark the edges on both sides, and both point in turn to San Marcuola in the distance.

The composition sketch for this painting surfaced some years ago. Except for a few details in the arrangement of the ships, the drawing agrees completely with the painting. The shadows, too, are indicated precisely.

Canaletto has included a curious detail: a depiction of a boat on the wall of the building in the right foreground. Whether this was simply sgraffito or some form of trade sign is not entirely clear. Above it a woman looks down from a small balcony; Canaletto placed similar figures at the edge of a number of his pictures, in order to close off the scene. He also perhaps was trying to convince us that there were in fact vantage points from which the panoramas he shows could be viewed.

This work is from a group of early pictures by Canaletto, now in Dresden, which were part of the Elector of Saxony's collection during Canaletto's lifetime.

There are many gondolas on the water, busily crossing the Grand Canal and, in one case, nearly colliding with a rowboat. Directly in front of Palazzo Corner Spinelli lies a cluster of barges of various kinds, tied together for lack of space to dock; the narrow quay on the right is apparently reserved for gondolas. The northwestern light is pale and damp; the sky seems to be clearing after a rainy afternoon.

It would still be possible to enjoy this view, were it not for the fact that there are two views involved. The right half of the composition was taken from the northeastern corner window of Palazzo Garzoni, the left half from that in the northwestern one. Canaletto must have made two preparatory drawings and then combined them in one composition, with the result that the picture encompasses an angle of almost ninety degrees.

Various features of this picture are arranged like the lighting and props in an operatic production, in order to create a compelling rather than simply descriptive image. These features perhaps refer to Canaletto's early experience in the theatre. The ominous sky provides an element of menace and restlessness rare in his work, and the unlikely grouping of boats in the right foreground seem to have been placed for picturesque, rather than a realistic, effect.

_ca_1725.jpg)

Canaletto was to return to paint this view on a number of occasions, and it is instructive to compare this, his first interpretation of it, with a later treatment (in the Royal Collection, Windsor). In this picture the agitated brushwork effectively evokes a stormy sky and blustery breeze. By contrast, in the later painting the scene is one of far greater serenity, with no sails billowing in the wind, and all the architectural details clearly described. The comparison illustrates more than simply a shift in style, however; it suggests Canaletto found a challenge in reworking a familiar subject, so creating a quite different experience for the viewer. The magnificent Baroque Church of Santa Maria della Salute, designed by Baldassare Longhena, dominates the scene at the right. To the left of center, in the middle distance, can be seen the Doge's Palace, and further over the Campanile of San Marco.

Canaletto was to return to paint this view on a number of occasions, and it is instructive to compare this, his first interpretation of it, with a later treatment (in the Royal Collection, Windsor). In this picture the agitated brushwork effectively evokes a stormy sky and blustery breeze. By contrast, in the later painting the scene is one of far greater serenity, with no sails billowing in the wind, and all the architectural details clearly described. The comparison illustrates more than simply a shift in style, however; it suggests Canaletto found a challenge in reworking a familiar subject, so creating a quite different experience for the viewer.

It is probable that this work was acquired by the Ambassador of the Holy Roman Empire to Venice at the annual exhibition of paintings held outside the Scuola di San Rocco, which Canaletto later depicted. Works were displayed at such exhibitions by many leading painters of the time.

To judge from the commercial success of Carlevaris's print series Le Fabriche, e vedute di Venetia of 1703, a lively interest existed in what might be described as portraits of actual buildings and in the more broadly conceived townscapes. However, Canaletto only began producing work in this genre in the 1730's, at the instigation of English patrons. Of his early work this painting comes closest to being an actual portrait of a building, although the church is set in a somewhat more spacious architectural scene. In this and other respects as well the painting is very reminiscent of the 'Santi Giovanni e Paolo and the Scuola di San Marco' and the 'Grand Canal near Santa Maria delta Carita', made for Stefano Conti. For instance, the most important building is not centered. There is a strong contrast between the heavily shaded area on the right and the brightly lit facade of the small church, which is emphasized as a result.

Canaletto made a precise graphite or chalk drawing of the church using a ruler and compass in order to achieve as accurate a likeness as possible. The brushwork is loose but careful, with particular attention given to subtle nuances in the colored surfaces, such as the reddish-ochre stucco on the church façade.

It is remarkable that Canaletto devoted so much attention in his early work to Venetian ecclesiastical architecture of the Middle Ages and Renaissance in particular, and so little to the more modern architecture of his own day. It was only in the 1730's that he turned to contemporary architecture, and this thematic shift runs parallel to and may also be connected with a fundamental change of style.

As is often the case with Canaletto's compositions, the original idea was Carlevaris's, but the older master had lacked the talent to do much with it. Here Canaletto opted for the traditional vanishing point on the central axis, which irresistibly draws the eye into the depth of the composition. In the exhibited work the vanishing point lies just behind the left-hand corner of the 'Scuola di San Marco'; the massive structures that constitute the main subject of the picture are thus situated almost entirely to the right of the central axis. At first sight the facade of the Scuola seems to close off the scene in the distance, but the small bridges along its left flank guide the eye an astonishing distance from the city, as far as the trees on the island of San Michele.

To the left, the composition is balanced by the darkness of the 'Rio dei Mendicanti' and the heavy shadow which hangs over the area behind it; a cloud outside the perimeter of the painting provides a pattern of light and darkness in the sky. Again, the sunlight is sultry rather than radiant.

Thematically, the present canvas and the 'Santi Giovanni e Paolo and the Scuola di San Marco', also representing a medieval church, form a lovely pair next to the two views of the Grand Canal, but it is unclear to what extent this was actually intended.

In this painting as well, the field of vision covers an angle of approximately ninety degrees. We may assume that Canaletto again began by making at least two topographical drawings on the spot, combining them in a single composition back in his studio.

_1726_28.jpg)

The dominant hues and tones are warmer and lighter than in the artist's earlier paintings, and as such mark the direction his work was increasingly to take. The topography is accurate and the site a famous one - a combination particularly favored by English Grand Tourists.

The early views of the Piazza San Marco and the Piazzetta, dating from before 1730, comprise four vertical compositions and two of horizontal format. Conceived as a series, it is almost certain that they were hung in one of the rooms in the Palazzo Mangilli-Valmarana on the Grand Canal where Smith lived. Only two of the paintings look out from the Piazzetta. The present example shows the view across the entrance to the Grand Canal with the Baroque church of Santa Maria della Salute, designed by Baldassare Longhena, and the Dogana in the background.

Canaletto has made several major adjustments in the disposition of the proportions of the buildings and other architectural motifs. The placing of the column of San Teodoro has been altered and its height has been increased. The steps of the bridge, the Ponte della Pescheria, by the Biblioteca Marciana have been brought forward. Similarly, on the other side of the Grand Canal, the Dogana is positioned in too close proximity to the Salute. Comparison with the preparatory drawing shows that Canaletto originally included the column of San Marco on the left of the composition, but in the painting he omitted this in favor of a boat and instead inserted the column of San Teodoro by the Biblioteca Marciana. The balance of the composition is, therefore, heavily weighted to the right. These alterations to the spatial intervals and the amalgamation of viewpoints are highly characteristic of Canaletto's working methods. Such shifts of emphasis also confirm the likelihood that the paintings were made for a specific setting and that the compositions were closely discussed with the patron. Several changes are visible to the naked eye. The paint is freely handled throughout, especially with regard to the figures in the lower right comer. The use made of mathematical instruments, mainly for drawing the outlines of buildings, is also apparent. The chiaroscural treatment of the light and the silhouetting of the buildings against the sky are the basis of the drama that characterizes Canaletto's early style, especially in the paintings done for Consul Smith.

The buildings in this view of the Piazzetta can be readily identified. The Biblioteca Marciana designed by Jacopo Sansovino is on the left with the Campanile and Loggetta visible immediately behind. Across the Piazza is the Torre dell'Orologio with the east end of the Procuratie Vecchie extending to the left and the beginning of the Campo San Basso to the right. The façade of the Basilica di San Marco dominates the right side of the picture together with the column of San Teodoro. The figure in red, gesticulating in the foreground just to the left of centre, is a Procurator who appears to be attended by a secretary or notary. Once the buildings are identified, the degree to which Canaletto has conflated two separate viewpoints and altered the proportions in order to achieve a unified composition becomes apparent. Thus, the height of the Campanile is exaggerated and the projected distance between the viewer and the Torre dell'Orologio lengthened. Other changes include the positioning of the flagpoles and the column of San Teodoro. Most of these topographical adjustments (but not the positioning of the flagpoles) are apparent in the preparatory drawing, which may have been made by the artist for discussion with his patron.

Canaletto shows on the far left a section of the Palazzo Balbi, to the right the Palazzo Contarini dalle Figure and the four palazzi of the Mocenigo family. In the distance we can see the Rialto Bridge, and beyond that to the right the roof of the church of SS. Giovanni e Paolo. In none of his other vedute has Canaletto placed such a curiously manned gondola in the foreground: the vessel, decorated with green twigs, contains two figures in Commedia dell'Arte costumes who seem to have escaped from the stage. The gondola, readied for a delightful picnic trip, is the scene of a marital drama, for the ugly old woman is clearly beating the man over his pointed hat with her oar, as he holds a tightly bundled infant out to her imploringly.

Smith commissioned a series of six large canvases from Canaletto showing freely conceived, theatrical views of Piazza San Marco and its surroundings intended for his own house, followed by a number of views of the Grand Canal. This project was extended into a series of twelve views, which Canaletto had published between 1730 and 1735 under the title 'Prospectus Magni Canalis Venetiarum'. A second edition followed in 1742, supplemented with twenty-four additional views.

These subjects became extremely popular and were rethought by Canaletto and his studio with small variations for a number of other clients. Canaletto executed related drawings which both he and his assistants could use as a guide when plotting these views.

The buildings are depicted accurately and in some considerable detail. Such precision contrasts with the liquid freedom of the application of paint used to place the cloud forms above. The figures in the foreground include oriental traders, shoppers, vagrants, servants, children and a youth who reclines nonchalantly in the sunshine.

Canaletto executed some paintings for the Imperial ambassador to Venice, Count Bolagnos, recording the ceremony of the presentation of his credentials to the Doge in 1729. The resulting two paintings, the 'Reception of the Ambassador in the Doge's Palace' and the 'Bucintoro Returning to the Molo on Ascension Day', are now in private collection. The latter is considered to be one of Canaletto's highest achievements.

At the end of the 1720's there was a demand for Canaletto's topographical work on the part of prosperous English tourists. In response to this situation Canaletto's work underwent great changes. The size of his paintings decreased, making them easier to ship. However, the atmosphere also changed. Well-bred tourists wanted to have a reminder of Venice not as a stage decoration with ghost-like shadows and sultry skies, but as the ideal Mediterranean city. They admired attractive, beautiful and above all recognizable buildings, harmoniously arranged and painted in soft colors under a bright blue sky with the merest hint of a white cloud.

Between 1727 and 1730 Canaletto became a master at this new genre, one he was largely responsible for creating. He no longer prepared the canvases with a reddish-brown but with a beige or a light grey ground. The paint was further diluted and more smoothly applied, with only a couple of perfectly measured, thickly applied strokes for clouds and figures. With the help of his assistants, Canaletto produced hundreds of paintings of this type, often in pairs, sometimes in series of twenty or more. Although the quality of the routine production slowly but surely declined in the course of the 1730's, Canaletto nevertheless also painted a number of works of very high quality in these years. The present painting is a good example of this kind of work made for the new tourist market.

This view is taken near San Biagio, looking toward the west along the Riva degli Schiavoni. From right to left we see the corner of the present-day Museo Storico Navale, a building on the corner of the Rio dell'Arsenale that has since been demolished, a warehouse, the campanili of San Giovanni in Bragora and San Giorgio dei Greci, the Molo with the Ducal Palace and the Campanile of San Marco and, behind the masts, Santa Maria della Salute. On the far left a small point of the island San Giorgio Maggiore can just be discerned. The Bacino di San Marco is filled with a variety of boats, including two with a lateen sail and a three-master. The lines directed toward the vanishing point of the footpath on the right invite the spectator to cross the bridge together with the pedestrians and to walk further along the quay. Thus the eye is led toward the horizon and back over the boats to the foreground.

It was McSwiney and above all Smith who stimulated Canaletto to specialize in wieldy topographical views for the tourist market and Canaletto became a much sought-after artist in this genre. He was so successful in fact that in the course of the 1730's, assisted by his pupils, he must have produced hundreds and perhaps even more views, occasionally in series of twenty or more.

This painting is a good illustration of Canaletto's achievement as a subtle colorist; he has effectively contrasted the powder-blue sky with the green water and the tan and orange brickwork and roof-tiles. In addition he has created formal interest by carefully observing how the Scuola to the far right of the picture casts diagonal shadows across the facade of the church. This work was owned by Joseph Smith and while in his collection it was engraved by Visentini as part of the Prospectus Magni Canalis series of prints.

Venice's reputation as a city of festivities was amply justified. This painting, along with its companion picture ('Return of the Bucentoro to the Molo on Ascension Day', also in the Royal Collection), record two of the most spectacular. Here a gondola race which formed part of a Regatta held on the Grand Canal is depicted. Such events had been organized since the fourteenth century as part of the Carnival, and were also occasionally arranged to honor notable visitors to the city.

At the extreme left of the picture is the macchina (an ornate temporary structure) under which the winners of the races were presented with flags. It bears the coat of arms of Carlo Ruzzini who ruled as Doge of Venice from 1732 until 1735. Spectators fill boats along either side of the Grand Canal, and observe the race from the balconies of the palaces, many of which are decorated with hangings. The eight-oared barges have been specially decorated for the occasion, and a number of the figures, notably in the foreground, wear Carnival costumes, such as the tri-corn hat with a white mask and black cape.

An engraving of this work was included in Canaletto's Prospectus series of 1735. The composition was clearly popular - other similarly accomplished versions of it are in the collections of Woburn Abbey and the National Gallery, London.

Here, a naval victory over Dalmatia which took place in 998 AD, apparently on Ascension Day, is commemorated. During the event the Doge travelled in the Bucintoro, the golden barge, out into the Lido, where he cast a ring into the sea, as a symbol of the marriage or union between Venice and the Adriatic. Such a ring had been given to a twelfth-century Doge by the Pope in gratitude for his peacemaking.

The massive barge, designed by Stefano Conti and the last to be built before the fall of the Republic, has just returned from the Lido. The spectacle it creates, with its huge, brilliant orange flag fluttering before the sky, was clearly one that appealed to Canaletto. It is perhaps the archetypal Venetian scene, combining as it does elements of beauty, showiness, symbolism, and sheer delight in the physical appearance of the city.

_ca_1732.jpg)

_ca_1732.jpg)

This painting is one of twenty four works by Canaletto bought by the 4th Duke of Bedford which remain together at Woburn Abbey.

The powerful Venetian fleets were built in the city's Arsenal, or naval boatyard, which had been established in the twelfth century. This view shows its water entrance, with dry docks and a ship inside, and to the left the Great Gateway which was built in 1460.

Canaletto followed the preparatory composition he established on paper in the painting in most respects, although in the latter he placed the two towers either side of the entrance further apart. The diagonals of the wooden footbridge in the foreground effectively vary and break up what would otherwise be a very static composition based upon vertical and horizontal emphases.

_ca_1732.jpg)

This is one of the earliest and most beautiful of these paintings. The subject is the mills built in the Brenta River near Dolo. Canaletto represented the view towards the east from a tall house located on the dam in the river. The sun shines from the west, as indicated by the shadow of the house where the artist sat, which falls to the right in the foreground. On the left the quay, lined with the most prominent houses, the inn and the campanile of San Rocco, makes a wide curve. On the other side of the Brenta are some free-standing buildings and a covered wharf. In front of these on the right, outside the image, begins the canal through which the traffic is led round the mill by way of the sluices. Arriving in the background is a 'burchiello' with a striped cover glides along the bend at the right, and a third boat with a red roof disappears just around the corner. Boats and small barges are moored to the banks on either side of the river.

In the foreground we see the mill complex with a couple of unused millstones on the left and the basin which powers the paddles; the gates have been lowered. It is late afternoon and the villagers seem to have finished their work for the day. They take their ease on a sack of flour, do a bit of fishing or chat with neighbors. A lady dressed in red is greeted by a couple whose servant protects them from the sun with a parasol. This group in particular attracts our attention. They are apparently prosperous towns-people out for a leisurely visit in the country.

The serenity of the scene is achieved by means of the composition; in a very restful and astonishingly well-ordered fashion all the anecdotal and topographical elements have been grouped round the Brenta, which occupies only a small portion of the entire painting. Most of the composition is reserved for the blue and white of the sky, which harmonize wonderfully well with the browns and greens of the foreground, enlivened by the contrasting touches of red, white and blue of the elegant burghers.

_1730_35.jpg)

Canaletto's vision of reality is constructed on a perspective system, with a highly dynamical balance marked by a complex "choral" harmony. His art transcends mere documentary; he is the inventor of a seemingly scientific visualization in which the content of the scene reveals its true nature. The best proof that his are works of controlled imagination identified with reality is to observe the townscape of Venice after having scanned Canaletto's paintings. The city appears under a new guise, with striking forms and rhythms. The stage-set perspective that served Canaletto as a point of departure was fundamentally a means of showing through illusions something that was not there. He reversed this process in his painting: instead of applying theoretical perspective to an object in order to simulate another, he rediscovered an object's natural perspective.

Many versions of this composition exist and not all of them can be by Canaletto. The fact that such images were reproduced illustrates that there was a ready market for works of this type. In part they were inspired by the classical landscapes of the seventeenth century, but they also were conceived to appeal to the cult of ruins which developed during the eighteenth century - a trend fed by antiquarianism, archaeology and nostalgia.

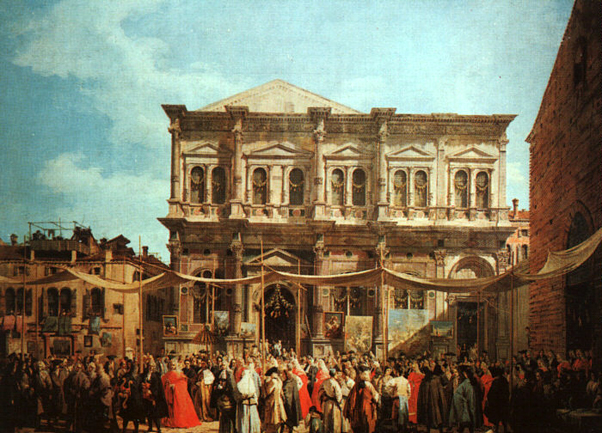

The Church of San Rocco at the right has housed the body of Saint Roch since 1485. In 1576 there was a very severe outbreak of the plague in Venice, and it was thought that his intercession prevented an even greater calamity, so from that year onwards his Feast day, 16 August, was celebrated by the Republic. Canaletto here depicts one aspect of the festivities - a procession of resplendent dignitaries emerging from the church after they have attended Mass.

The Scuola di San Rocco dominates the centre of the composition; its exterior is decorated with garlands and paintings, as was the custom on this occasion. Canaletto and his artist nephew Bellotto are recorded as having sold some of their works at one of these exhibitions. Many of the figures walking before it and beneath the awning can be identified because of their distinctive and colorful clothes. They are, from left to right: Secretaries, who wear mauve; the Doge's chair- and cushion-bearers; the Cancelliere Grande who wears scarlet; the Doge himself in gold and ermine; the Guardiano Grande di San Rocco; the bearer of the sword of state; the Senators; and finally the Ambassadors. A number of them carry nosegays, which were presented as reminders of the plague; they were carried during outbreaks of the disease because it was believed that their scent helped prevent its spread.

Canaletto shows an expansive view of this scene which could not, in fact, be observed, because the church of the Frari impinges too far on the near side of the square.

The Piazza is here shown as a lively center of commerce; stallholders cluster round the flag staffs and are protected from the sun by large colorful parasols. From left to right an impressive view of the San Marco, the Doge's Palace and a view of the Bacino, forms a backdrop to their activity. From this vantage point the artist shows a clear view of horses of San Marco which are set above the main door of the church; they were later to become the subject of one of Canaletto's most inventive capricci ('The Horses of San Marco in the Piazzetta', Royal Collection, Windsor).

The Molo is the busy area of waterfront on the seaward side of the Piazzetta. From this section of it is possible to get a splendid view of the church of Santa Maria della Salute and the customs house on the far side of the Grand Canal. Further to the left can be seen Palladio's church of the Redentore, which dominates the Giudecca.

The Church of San Simeone Piccolo, at the left, was rebuilt between 1718 and 1738 after a design by the architect Scalfarotto. It is depicted here completed, hence the dating of the painting to about 1738. Canaletto had earlier painted other versions of the same composition, including a picture in the Royal Collection which was engraved by Visentini as part of the Prospectus Magni Canalis series of prints.

This view of the upper reaches of the Grand Canal is now considerably altered by the city's modern railway station which dominates and disrupts its right side. The artist has depicted some craft plying their way across the canal, including a passenger barge at the left, but the scene is a relatively peaceful one. He seems to have been particularly preoccupied with the gently distorted mirror-image of the buildings reflected on the surface of the water.

_1738_40.jpg)

The situation changed around 1740. The lucrative tourist market collapsed as a result of the outbreak of war throughout Europe. Smith continued his efforts to help Canaletto secure commissions for idealized views in a classical style and also published a series of etchings of capriccios, but the returns were not high enough. In 1746 Canaletto left for his clients' homeland, England.

The arch was built by the Emperor Constantine in the fourth century, to commemorate his victory over Maxentius. The view is playfully manipulated; the friezes and inscriptions he chose to depict are those which can be seen on the north side, but it is painted as though looked at from the south. Through it can be seen the church of San Pietro in Vincoli, and to the right the edge of the Coliseum. The main group of figures in the foreground, one of whom points with his stick, are probably Grand Tourists who have come to admire the ancient glories of the city.

The seated figure at the left, who has beside him a portfolio and ruler and is either writing or drawing, may well be intended as a self-portrait. This is particularly suggested by the figure's proximity to Canaletto's rather grand inscription asserting his authorship and the date of the painting, in a manner that replicates the carvings on the arch.

_1742.jpg)

The Forum was the site of the political and religious center of ancient Rome; attempts to excavate it were made throughout the eighteenth century, and the ruins revealed were consistently revered by visitors to the city. The tourists shown here mainly scrutinize the remains of the temple of Castor and Pollux which dominates the foreground. One man, at the right, is so intent upon the ruin that he appears to be ignoring the cleric in black who is attempting to converse with him. Further back, at the left, between the columns can be seen a knife grinder, and over towards the right, the Temple of Saturn. Rising up above it is the Palazzo Senatorio which dominates the Capitoline Hill. These topographical elements have been depicted with considerable care, but elsewhere the artist has taken liberties with his subject - some of the houses at the left are invented, and their chimneys appear characteristically Venetian, rather than Roman.

This austere capriccio is actually one of weakest of the 'overdoors' in terms of quality, but nonetheless of interest. The very fact that it is poorly executed is a useful reminder of Canaletto's practice of employing assistants; he would probably have planned the composition, and then perhaps because of a need to finish the commission quickly allowed a member of his studio to carry out most of the work.

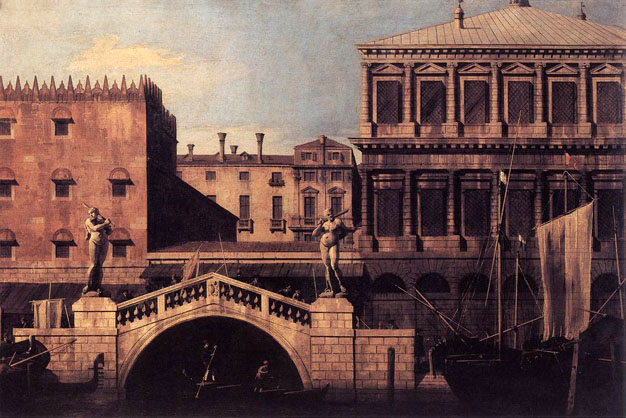

The view is shown as though seen from the Bacino: at the left are the state granaries, and to the right the Zecca, or Mint. Between them is the Ponte della Pescaria, and beyond, the rear of the Procuratie Nuove. The artist has made the little bridge look more theatrical and impressive by depicting on it statues by Aspetti and Campagna which are in reality at the entrance to the Biblioteca Marciana.

In the 1740's the horses were above the loggia at the entrance to San Marco. They were only removed from this position in 1798 when Napoleon's troops overtook the city and were then taken to Paris, but returned to Venice in 1815.

The dramatic arrangement of these horses on pedestals is entirely fictional. It is possible that it is intended to convey the frustration felt by many at not being able to study the horses properly above the loggia. For example, the Neo-classical sculptor, Antonio Canova (1757-1822), suggested that they should be set either side of the entrance to the Doge's palace so that they could be seen to better advantage.

In his earlier interpretation of the subject (ca 1725) the artist included the whole of the great church, but in this work made the bold decision to crop it at the top, as though to imply that the building could not be contained within one picture. Its enormous size is contrasted with the groups of figures by the waterside: ladies and gentlemen enter the church through one doorway, while a senator, dressed in red, emerges from another.

In about 1740, besides vedute ideate, Canaletto began to invent much more fantastic variations on the buildings and landscapes he had long painted 'al reale' in the form of 'capricci'. Nor was he alone in this. Tiepolo and Piranesi also published series of fantasy prints called caprices in the 1740's. A contemporary dictionary of art defined a capriccio as 'an artificial and bizarre composition which opposes the rules and beautiful models of nature and art, but which pleases through a certain lively particularity and a free and bold execution.' Conceived in that sense, the capriccio is the opposite of a veduta ideata, and both the etched and the painted caprices that Canaletto made during the early 1740's meet that description. The present canvas is one of the most beautiful examples.

Across two islands or peninsulas, connected by an impossibly fragile arched bridge, the eye is led toward a third, distant island in the Lagoon, behind which others appear. From the bridge a path leads to the right over a second, small bridge to a gate in Renaissance forms with a curious passageway placed crosswise, with a tiled roof crowned by a stone statue standing guard. To the right are the remains of a wall and a tower, like the gate partly decorated with stone facings. To the left of the bridge a path runs to a chapel with an asymmetrical roof, a tall aisle with a balcony and a loggia on the right side. Behind the campanile rises a façade with a sign indicating that it is an inn. On the third island stands a heavy, square tower. The time is about sunset; on the left, a pale moon rises. A washerwoman, travellers and fishermen populate the scene.

On closer inspection it appears that, with his supposedly randomly selected elements, Canaletto actually ordered his composition entirely in accordance with traditional practice. The placement of the elements in space and the manner in which the eye is led into the distance along the imaginary buildings in leaps is harmonious rather than abrupt. The appealing melancholy evoked by the scene is new; it is the result of the ostensible purposelessness of these friendly structures which are arranged haphazardly in the quiet light of the setting sun and the rising moon.

In Canaletto's art, a strict distinction between veduta ideata and capriccio seems difficult to maintain. No wonder he referred to his own series of etched landscapes as 'views partly taken from life, partly imagined.'

The bridge and extraordinary circular temple at the left appear to be almost entirely imaginary. Such spectacular flights of fancy may at root be based on reminiscences of details in works by Claude Lorraine (1600-82) and Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-78), but Canaletto has transformed possible sources of this type into a decorative creation all of his own.

While the bridge and the buildings appearing on the companion piece are almost entirely imaginary, in this picture it is possible to locate the origin of a number of the buildings. The bridge is the same in both pictures, and the large structure to the right of it is copied from Andrea Palladio's 'Palazzo della Ragione in Vicenza'. Part of the attraction of these works was clearly spotting such borrowings and in doing so displaying one's knowledge.

In 1746 Canaletto left for his clients' homeland, England, where he remained with one short interruption until 1755. Once in London he initially received several good commissions, but all things considered business proved to be disappointing; too many people already owned his paintings. More serious were the complaints about the declining quality of his work.

In this picture he combines a view of its whole span with a depiction of festivities, which, although tamer than the Venetian spectacles he generally painted, partially recall them. The celebrations accompanied the appointment of the new Lord Mayor of London. The largest City Barge is shown taking him to Westminster Hall, by the Abbey at the right, where he will be sworn in. The prominent building on the horizon to the left of it is Saint John's Church, Smith Square, and over on the other side of the river is Lambeth Palace, the London home of the Archbishop of Canterbury. All the other spectacular barges are those of the different city guilds (Skinners, Goldsmiths, Fishmongers, Cloth workers, Vinters, Merchant Taylors, Mercers and Dyers); a number of them are firing salutes to honor the Mayor. In order to encapsulate all of this activity within such a broad panorama Canaletto has adopted an imaginary vantage point high above the Thames.

The arch has been used carefully so that it does not flatten the image. It is placed just off center, looked through at a slight angle, and the uniformity of its shape is broken by the simple device of a bucket being lowered on a rope. It acts like a giant eye or lens and focuses attention on the cityscape beyond, which includes the Water Tower and York Water Gate at the left, and Saint Paul's Cathedral at the right. In the center can be seen the spire of the church of Saint Clement Danes. The delicate peach coloration of the clouds above, suggests this is a rare instance of Canaletto attempting to depict dusk.

The painting is thought to have been commissioned by Sir Hugh Smithson, who was to become the Duke of Northumberland. He was one of those responsible for overseeing the construction of the new bridge.

Whitehall is shown as an open space surrounded by small buildings, unfamiliar to modern Londoners accustomed to vast government offices covering the area. The Tudor Treasury Gate at the left was demolished in 1759 to ease the flow of traffic, but the Banqueting House, left of centre in the middle-distance, and Church of Saint Martin-in-the-Fields beyond and to the right of it, remain.

A sense of order has been imposed on the urban sprawl; the main buildings lie parallel to the picture plane, and the perspective is conveniently established by the walls and pathways which run towards the centre of the composition. Everything - from the chickens in the foreground to the houses half a mile away - is observed with a crispness of equal insistence, so creating a vivid record of this unexpected view of the capital during the reign of George II.

Canaletto later reinterpreted the scene from a lower viewpoint, and produced an even wider panorama (one of his most spectacular), which includes a view of the Thames at the left.

The terraces in the foreground belong to Richmond House and, at the left, Montagu House. The figures on them parade, converse, and in a leisurely manner watch the spectacle of the river in the sunshine. While a number of smaller boats skull about on it, two larger decorated barges belonging to the City of London, make their way upstream. A related drawing of the scene shows a broader view, with far more traffic on the Thames.

The vertical emphases of the church spires, chimneys at the left, and mooring posts in the foreground, all carefully anchor and balance the composition, which is principally ordered by the horizon and gentle diagonals of the river bank.

The building is viewed from Castle Meadow, with the Castle Mound at the left and at the right a view of the town. On the River Avon in the foreground is a Venetian-style pleasure boat: this apparently incongruous detail may be explained by the fact that Lord Brooke had visited Venice and is known to have owned a decorated boat.

This is, however, far from simply being a work of antiquarian interest. The painter has filled the scene with a variety of figures ranging from the regiment of the King's Life Guard's who drill in the background to the footmen at the right who beat a carpet, near to the entrance to Downing Street.

The painting is related to a working drawing in Canaletto's Accademia sketchbook (Galleria dell'Accademia, Venice).

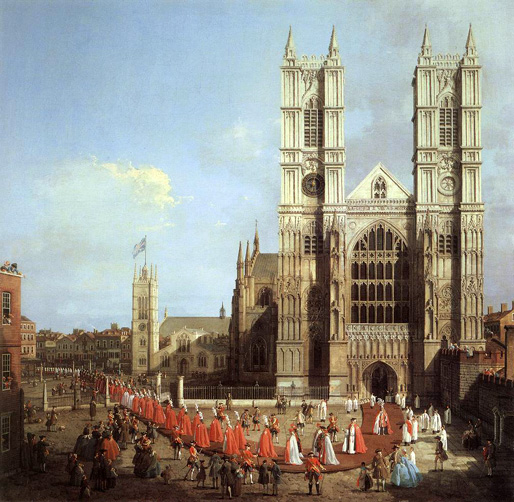

The knights have emerged from the west end of the Abbey and walk round past Saint Margaret's Church, beyond which can be seen the roof of Westminster Hall. The Abbey is shown after its recent restoration and the construction of the two west towers, an undertaking which was carried out by the architects Nicholas Hawksmoor and Sir Christopher Wren, and the picture in many ways acts as much as a commemoration of their achievements, as of the ceremony.

Canaletto may have based his depiction of the event on descriptions, rather than actually having witnessed it: the resplendent knights are impressive, but they are rather stilted in arrangement, and their scale in relation to the architecture is not completely convincing.

Canaletto also made a companion picture for the painting (also in the Birmingham museum), which perfectly complements it, as a depiction of the same side of the castle from the interior lawn. He has filled this canvas, from left to right, with Guy's Tower, the Clock Tower over the entrance gate, and Caesar's Tower.

Canaletto created far more than just a celebration of a particular building, however; he also provides us with an invaluable record of its surroundings, and a vivid impression of the capital coming to life early in the morning. To the right is the statue of Charles I by Hubert Le Sueur (ca 1595 - 1650) that now stands at the entrance of Whitehall from Trafalgar Square, and at the left is the entrance to the Strand and the Golden Cross Inn, which has a sign standing in front of it.

The painting was much copied and engravings were made after it; as a result of the distribution of these copies, it was to have a significant influence on the work of English artists who depicted urban scenes.

Canaletto has created a slightly 'wide angle' effect by combining what can be seen of the hospital from two separate viewpoints which are set a little way apart on the near side of the Thames. He has slightly broken the potential symmetry of the composition by studying the buildings from a little left of centre. In addition, the monotony of the river is relieved by the considerable variety of craft that is travelling up and down it, and also by the unrelenting verticals and horizontals of the design which are countered by the bold diagonal of the mast of the ship grounded at the right.

The river and architecture were established first by the artist, and the boats then painted over the top; it is just possible to see the buildings through the sails of the boat to the left of the centre of the picture.

This picture was painted for Thomas Hollis, a significant patron of Canaletto, who owned nine works by him. On the reverse it bears an inscription, which when translated from the Italian reads 'Made in the year 1754 in London for the first and last time with the utmost care at the request of Mr. Hollis, my most esteemed patron - Antonio del Canal, called Canaletto.' It may well be the case that Hollis requested that the canvas be inscribed in this way in order to certify its authenticity.

The view may not be an accurate record, but it is carefully composed, with the tree framing it at the left and a darkened foreground leading the eye of the viewer on into the middle-distance. The figures who fish, punt and stroll by the water effectively animate the scene.

This work is an ingenious combination of Italian and English influences - a fitting project for Canaletto to work on prior to his final return to Venice, after having spent nearly a decade in England. The general disposition of the hilly landscape and the vegetation appear English, and a bridge inspired by Westminster Bridge has been placed in the middle distance. The Corinthian column, however, decorated with an escutcheon and surmounted by a statue of a saint, and the triumphal arch, are clearly Italianate. The juxtaposition of these two sets of references cleverly and subtly encourages you to question what is real, and what is imagined.

Old Walton Bridge was painted for Thomas Hollis; it bears the inscription on the reverse 'Made in the year 1754 in London for the first and last time with the utmost care at the request of Mr. Hollis, my most esteemed patron - Antonio del Canal, called Canaletto.' According to an old catalogue of the Hollis collection the three standing figures to the right of the artist are Hollis himself, his friend Thomas Brand who inherited the painting, and his Italian servant Francesco Giovannini; the little animal between them is Hollis's pet dog, Malta.

From 1756 until his death in 1768 Canaletto continued working with varying degrees of success. Though often relying on old sketches, he occasionally invented surprising new subjects and compositions. With the possible exception of an interruption in the 1730's, Canaletto continued painting free compositions in the form of 'vedute ideate' or capriccios as well as the accurate town views. Canaletto's fame, however, was based on the 'veduta esatta'. Like Van Wittel, Canaletto won official recognition only in old age with his admission to the Venetian Accademia in 1763 for the genre he had made popular in Venice and throughout Europe. Apparently, in keeping with tradition, his colleagues continued to view this specialty as one of modest artistic importance.

It is highly likely that for this composition Canaletto used the "optical camera", an instrument which facilitated the control of perspective in such a wide and "unnatural" field of vision. The stamp of naturalness is produced in any case by the immediacy of the boatmen's movements and by the temporary balance created by the boats crossing.

Canaletto painted a view looking towards the rood screen, decorated with garlands at the east end of the church, from a point near to the entrance. Beneath the arcade to the left of the nave a priest can be seen officiating at a small altar. Canaletto has effectively captured that most elusive of effects - the way the little light which enters the building plays upon the extensive mosaic decoration above. Many people are shown at prayer, and two small dogs cower in the right foreground.

It has been suggested that the artist was consciously displaying his ingenuity in such works, in order to impress the Venetian Academy of Fine Art which he was seeking to join at the time.

The viewpoint complements that of the painting's companion picture ('Piazza San Marco: Looking East from the South West Corner'), which is also in the National Gallery, London. Both pictures are painted in what has been called Canaletto's late 'calligraphic' style, in which he employs a shorthand of dots and curved lines in order to place details such as highlights on figures.

A particularly attractive contemporary drawing, which can be associated with the composition, shows the view extending some way towards the left, so that it is possible to see the Torre dell'Orologio. This worked up sketch probably preceded the painting and a group of other related works by Canaletto.

From the bank between the water and the houses the view is toward the west, where the church of Santa Marta closes off the buildings. To the left of the church the silhouette of the island of San Giorgo in Alga appears on the horizon, in the left corner is a house on another small island. Fishing boats decorated with balloons sail about, while tents and windscreens for the many musicians and cooks are spread over the grounds. A gondolier's assistant and his lady dance the furlana to the accompaniment of violin, guitar and tambourine, while a distinguished- looking foreigner is cajoled into dancing by a woman of the working class.

The multitude of diverse visual elements has been neatly arranged by Canaletto along two crossing diagonals, with the church at the point of intersection. The artist chose a somewhat elevated vantage point, making it possible to survey a wide variety of individual scenes at the same time. It is not clear whether such a point of view was indeed possible on the spot. What is certain is that Canaletto first drew the various parts separately on several sheets; of these, two have survived with fragments of the houses in the background, which the artist must have sketched from different spots. With the help of these he built up the composition, according to a scheme identical to that of the diplomatic receptions painted on various different occasions. The painting is something of a humorous commentary on this: the people's festival supplants the public one, just as the moon does the sun.

Canaletto painted the canvas for the merchant Sigismund Streit, who was originally from Berlin. Streit had made his fortune in Venice after settling there as a young man in 1705. When he retired from business in 1750, he devoted himself to study and to the accumulation of a modest collection of paintings. Part of his painting collection has been preserved, including four canvases by Canaletto among them the 'Vigilia di Santa Marta and the Vigilia di San Pietro', another night view..

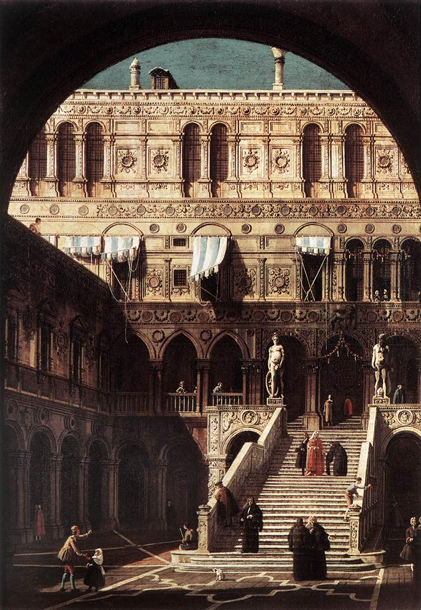

The Perspective - donated by Canaletto to the Accademia in 1765 for his admission in the capacity of a painter of perspective in September, 1763 - is a fine example of his extraordinary recreation of real data in prodigiously stylized form. Even though here the subject is drawn from the imagination, each architectural detail is a fascinating concentration of images.

This painting records the 'Vigilia di San Pietro' on June 28, the feast day of Saints Peter and Paul. San Pietro de Castello, the Church shown was the residence of the Republic's Patriarch and of great local importance prior to his move to San Marco. Backlit by the moon, this romantic vista is among Canaletto's most arresting, painted after his return from England in 1755-56.

Source: Art Renewal Center

Source: Canaletto Online

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.