Italian Early Renaissance Painter, Sculptor, and Architect

1267 - 1337

Giotto di Bondone , better known simply as Giotto, was an Italian painter and architect from Florence. He is generally considered the first in a line of great artists who contributed to the Italian Renaissance.

Giotto's contemporary Giovanni Villani wrote that Giotto was "the most sovereign master of painting in his time, who drew all his figures and their postures according to nature. And he was given a salary by the commune (of Florence) in virtue of his talent and excellence."

The later 16th century biographer Giorgio Vasari says of him "He made a decisive break with the Byzantine style, and brought to life the great art of painting as we know it today, introducing the technique of drawing accurately from life, which had been neglected for more than two hundred years."

Giotto's masterwork is the decoration of the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, commonly called the Arena Chapel, completed around 1305. This fresco cycle depicts the Life of the Virgin and the Life of Christ. It is regarded as one of the supreme masterpieces of the Early Renaissance. That Giotto painted the Arena Chapel and that he was chosen by the commune of Florence in 1334 to design the new campanile (bell tower) of the Florence Cathedral are among the few certainties of his biography. Almost every other aspect of it is subject to controversy: his birth date, his birthplace, his appearance, his apprenticeship, the order in which he created his works, whether or not he painted the famous frescoes at Assisi, and where he was eventually buried after his death.

Giotto was probably born in a hilltop farmhouse, perhaps at Colle di Romagnano or Romignano; since 1850 a tower house in nearby Colle Vespignano, a hamlet north of Florence, has borne a plaque claiming the honor of his birthplace, an assertion commercially publicized. He was the son of a man named Bondone, described in surviving public records as "a person of good standing". Most authors accept that Giotto was his real name, but it may have been an abbreviation of Ambrogio (Ambrogiotto) or Angelo (Angelotto).

The year of his death is calculated from the fact that Antonio Pucci, the town crier of Florence, wrote a poem in Giotto's honor in which it is stated that he was 70 at the time of his death. However, the word "seventy" fits into the rhyme of the poem better than would have a longer and more complex age, so it is possible that Pucci used artistic license.

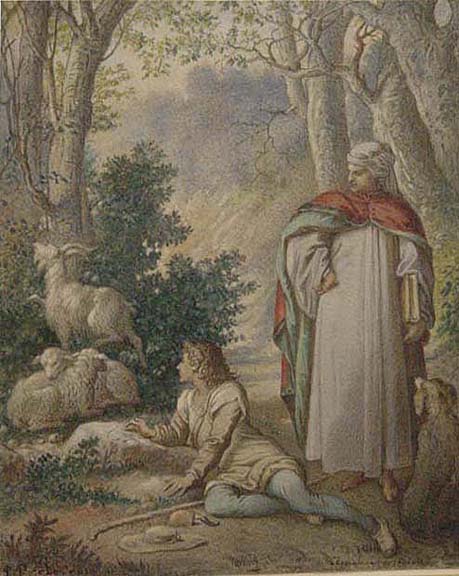

In his Lives of the Artists, Giorgio Vasari relates that Giotto was a shepherd boy, a merry and intelligent child who was loved by all who knew him. He was discovered by the great Florentine painter Cimabue, drawing pictures of his sheep on a rock. They were so lifelike that Cimabue approached Bondone and asked if he could take the boy as an apprentice. Many scholars today consider the story legendary and think it more probable that Giotto's family was well-off, and had moved to Florence where Giotto was sent to Cimabue's workshop as an apprentice.

Vasari recounts a number of such stories about Giotto's skill. He writes that when Cimabue was absent from the workshop, his young apprentice painted such a lifelike fly on the face of the painting that Cimabue was working on, that he tried several times to brush it off. Vasari also relates that when the Pope sent a messenger to Giotto, asking him to send a drawing to demonstrate his skill, Giotto drew, in red paint, a circle so perfect that it seemed as though it was drawn using a compass and instructed the messenger to give that to the Pope.

Giotto's master, Cimabue, was one of the two most highly renowned painters of Tuscany, the other being Duccio, who worked mainly in Siena. Around 1280, Giotto followed Cimabue to Rome, where there was a school of fresco painters, of whom the most famous was Pietro Cavallini. The famous Florentine sculptor and architect, Arnolfo di Cambio, was then also working in Rome.

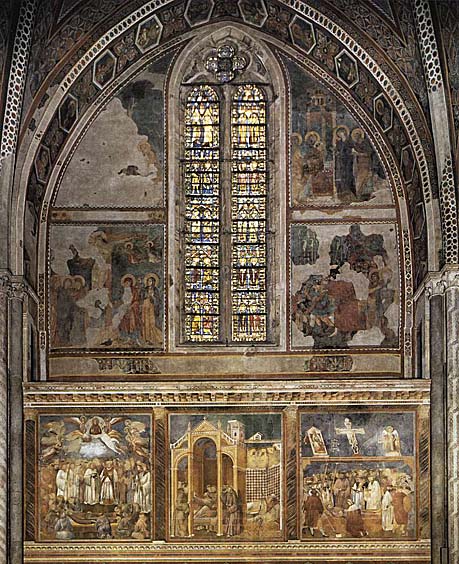

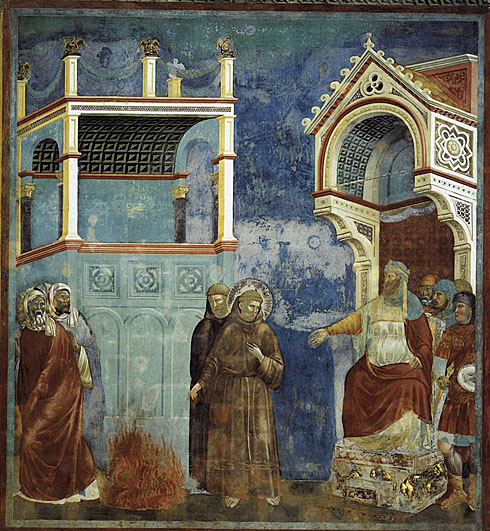

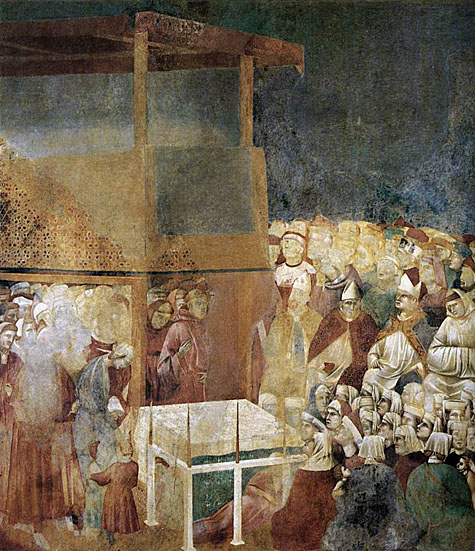

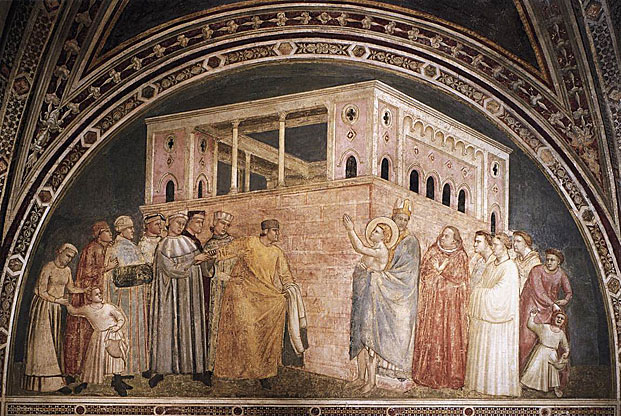

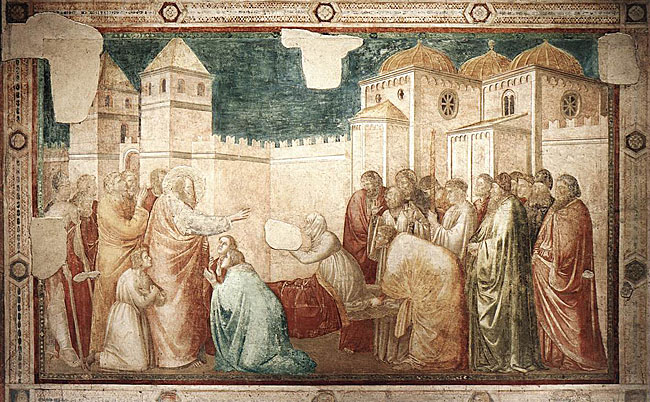

From Rome, Cimabue went to Assisi to paint several large frescoes at the newly-built Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi, and it is probable, but not certain, that Giotto went with him. The fresco cycle of the Life of St. Francis in the Upper Church is commonly considered to be the work of Giotto, but the documents of the Franciscan Friars that relate to artistic commissions during this period were destroyed by Napoleon's troops, who stabled horses in the Upper Church of the Basilica. In the absence of documentary evidence to the contrary, it has been convenient to ascribe every fresco in the Upper Church that was not obviously by Cimabue, to Giotto, whose prestige has overshadowed that of almost every contemporary. Some of the earliest remaining biographical sources, such as Ghiberti and Riccobaldo Ferrarese, cite the fresco cycle of the life of St Francis in the Upper Church as his earliest autonomous works. However, since the idea was convincingly put forward by the German art historian, Friedrich Rintelen in 1912, an increasing number of scholars have expressed doubt that Giotto was in fact the author of the Upper Church frescos. There are many differences between them and the Arena Chapel frescoes which cannot be accounted for by the stylistic development of an individual artist. It seems, rather, that several hands painted the frescoes and that the artists were probably from Rome. If this is the case, then Giotto's frescoes at Padua owe much to the naturalism of these painters.

Not long after the completion of the upper wall surfaces and of the vault in the Upper Church of San Francesco in Assist, work would have begun on the lower walls of the nave. At the request of the order, something was to be realized here which had never before been attempted in such a fashion - the history and progress of the great saint and founder of the order, whom the old people of the area might still be able to remember as a living person, were to be brought to the attention of the faithful in the form of a frieze. The intention was to develop a pictorial version of the life story of the saint, which would then act as the model for all further representations.

The patrons recognized Giotto as the artist best suited to this unique undertaking. This cycle of pictures has occupied generations of art historians. The questions of dating - whether they were painted shortly before or shortly after the first Holy Year of 1300 - and of authorship were judged particularly controversial. In most minds it was a question between a Roman artist, Cavallini, and the Florentine artist, Giotto.

The frescoes illustrate the complex decorative program realized in the nave of the Upper Church.

St. Bonaventure described the life of St. Francis in a great theological work as an example to the faithful. He divided the Saint's journey through life into ninety-seven stations, from which twenty-eight scenes were selected for the pictorial narrative, these being further identified by inscriptions. The life story begins in the fourth bay of the north wall, that is, directly adjoining the crossing, with the Homage of a Simple Man, and ends with the Liberation of the Heretic Peter (not by Giotto), a miracle ascribed to St. Francis after his death.

A simple man spreads out his cloak before the young nobleman. He alone recognizes that Francis deserves such an honor. While Francis receives the tribute with a terse gesture, the other bystanders react with a lack of understanding. The scene of the action is clearly established, for the temple, which marks the distance between the main protagonists, is the Minerva Temple in Assisi, which can still be seen today.

Francis hands his valuable golden cloak to an impoverished citizen. The scene takes place in front of two rocky hills, on whose peaks two very different types of architecture rise up - the world of the city and of the cloister confront one another here. The descending slopes meet behind the figure of the saint, emphasizing his position in the picture, as well as characterizing his situation in life: this is a first indication that the saint will decide to lead a secluded life of poverty.

According to the legend, the image in the church of San Damiano spoke to the young nobleman: "Francis, go and restore my house, which is in danger of collapsing". Giotto pictures Francis in a half ruined church, where the saint kneels before the painted crucifix, his arms raised in fright. This lively reaction and the perspective structure make the events in the picture particularly vivid and intelligible.

When Francis' father accuses his son before the Episcopal Tribune of squandering his fortune, Francis returns to him even the clothes he is wearing, and repudiates him. Giotto illustrates this sensational public separation, which signifies the decisive step towards the saint's future life of poverty, by means of the two groups of people on opposite sides. The buildings further reinforce the gulf between the two worlds.

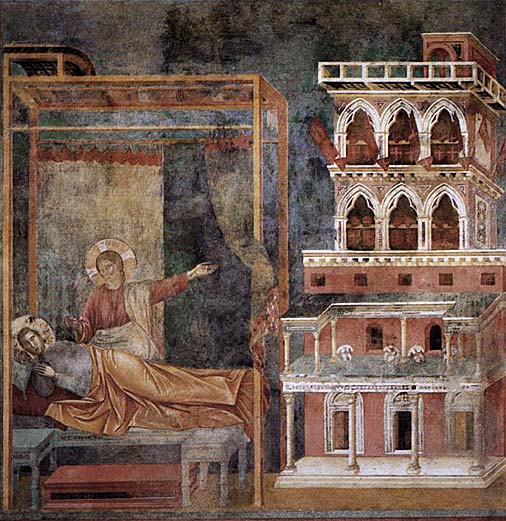

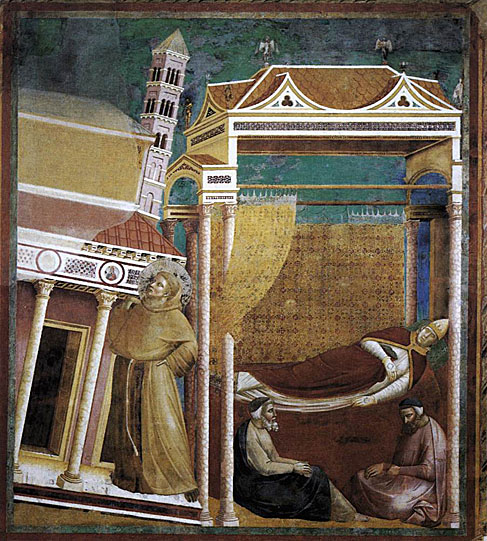

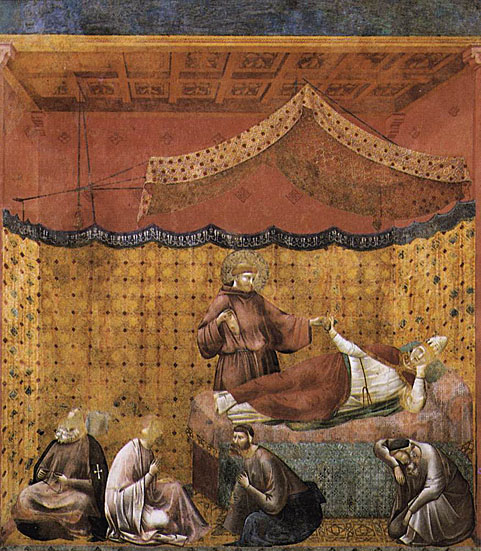

The composition of this scene is very similar to that of the Dream of the Palace.

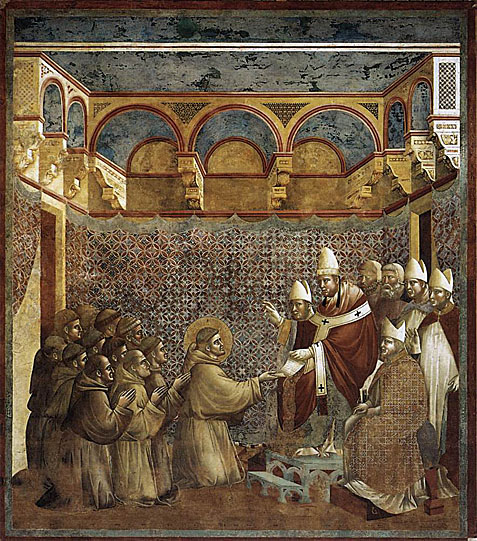

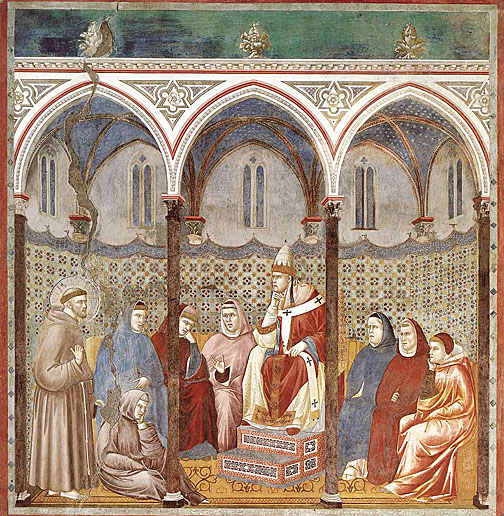

Following his vision, Pope Innocent III confirms the rule of the new Franciscan community. In a magnificent interior, constructed in perspective, the pope blesses the founder of the order and his rule. Francis' companions and the Church dignitaries follow the action with expressions of concentration. It is not least through this device that Giotto makes plain the consequences of what is taking place.

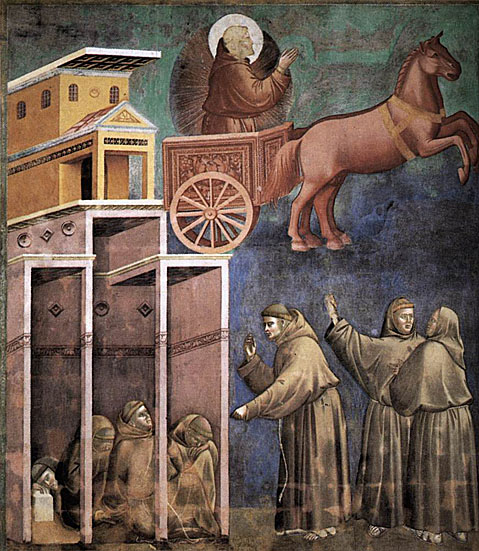

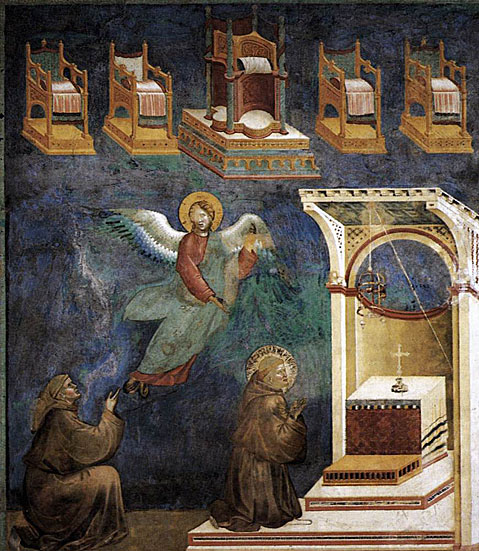

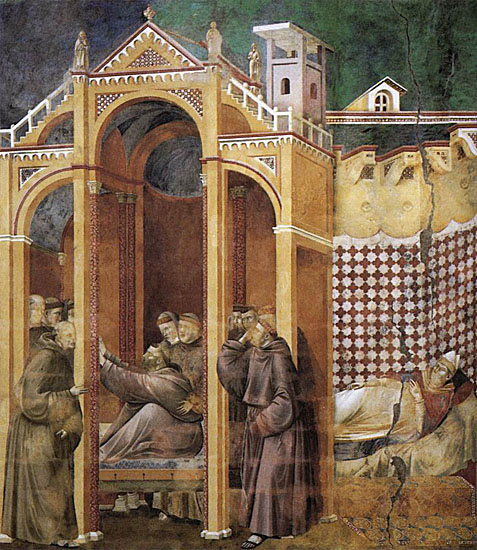

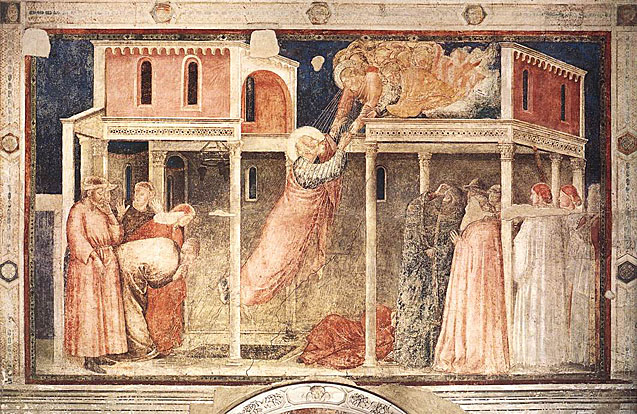

Several brothers of the order sleep in a confined architectural shelter, others stand next to it and gesticulate excitedly at the curious manifestation in the heavens: Francis, surrounded by a mandoria of golden rays, rides in a Roman chariot through the skies. The saint appears to his companions as the guide and new leader of Christianity. Giotto distinguishes the spheres of heaven and earth very clearly through his use of color. In an impressive manner, he makes evident the visionary character of the scene.

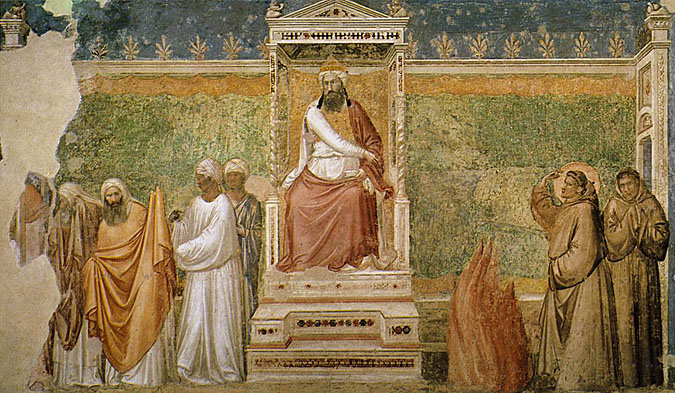

In order to convert the sultan to the Christian faith, Francis is prepared to undergo a trial by fire. The saint stands in the center of the picture, points to the fire and turns towards the sultan. The latter appears surprised and annoyed that his own priests are running away. Giotto pictures the anxious priests and the suddenly powerless sultan most vividly.

This scene was executed partly by assistants.

The five scenes from The Vision of the Flaming Chariot to St Francis in Extasy (No. 8-12) are characterized by inferior workmanship, especially in the figures. This scene was executed partly by assistants.

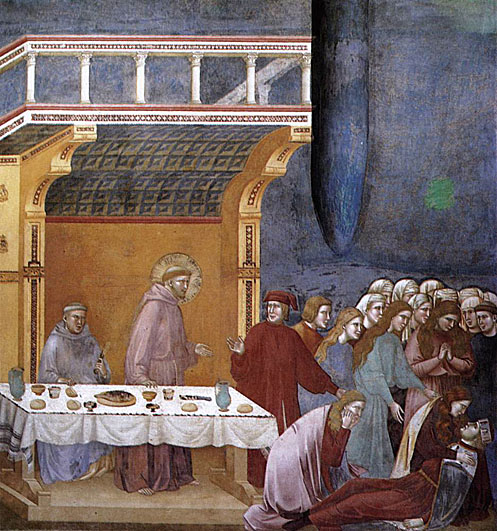

Francis had a crib built for the Christmas celebrations. At High Mass, in which he was participating as deacon, it was observed that he took a sleeping child from the crib and roused it. The representation of space is particularly impressive in this fresco. Giotto depicts the choir area behind the screen, to which the wooden cross, its back to the viewer, is attached.

The farmer, to whom Francis lent his mule as a mount, was tormented by thirst. Water comes bubbling out of the rocks in answer to the Saint s prayer. Giotto shows Francis praying fervently. The farmer, almost dying of thirst, collapses at the spring. As so often in Giotto's representations, figures - here the two Franciscans - comment on the scene with their glances and so anticipate the reaction of the viewer. It is interesting to point out the amazing precision with which the ass's packsaddle has been rendered.

The earthquake of autumn 1997 badly damaged the entrance wall, upon which this fresco is situated.

The two scenes on the entrance wall are the Miracle of the Spring and the Sermon to the Birds, the compositions in which the hand of Giotto is most apparent.

St. Francis came across a flock of birds that did not fly away at his approach. He gave a sermon to the expectantly waiting creatures, who only left the saint after receiving his blessing. As so often, Giotto makes plain the extraordinary nature of events through the reaction of a secondary figure - in this case, through the Franciscan friar, who raises his hand with a surprised expression on his face.

It is worthy to point out the table in the Death of the Knight of Celano, which is covered with a lovely embroidered table-cloth, and laid with food, crockery and cutlery.

Francis wanted to surprise Pope Honorius III with a well-prepared sermon; however, he lost the thread of what he was saying and had to improvise. His address captivated everyone and convinced them that the spirit of God spoke through him. Giotto expresses this through the different reactions of those listening, reflected especially in the lively facial expressions.

As he experienced with depicting space, Giotto's knowledge increased. In this fresco painted a three-dimensional "box" representing the hall. He then emphasized the space by cleverly arranging the architectural elements and human figures within it. This gives the figures volume, defined in space by the depth of the regular geometrical solids. The magnificent Gothic hall emphasizes the dignity of the pope and rhythmically articulates the group of figures.

During a meeting of the order, St. Anthony of Padua was preaching in the cloister at Aries - Giotto shows a generously proportioned Gothic room. Suddenly, Francis appeared. Giotto depicts the saint with outspread arms - the resulting shape of the cross alludes to his Christ-like life. Only St. Anthony, who had just been speaking about Christ and one other member of the Order notice the apparition. Giotto shows all the others listening with full attention. The figures seen from the back are also particularly impressive, the artist making the weight of the bodies plain for all to see.

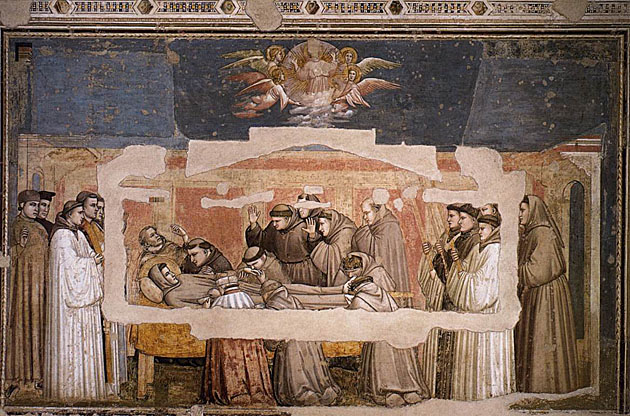

When Francis felt close to death, he had himself brought to a small church. He died there in the presence of his Brothers. The death of the saint and his ascending soul are here linked to the requiem mass to create a solemn representation peopled with many figures. This fresco is followed by a further eight pictures "peopled with many figures", which are often dated several years later than the other scenes.

Giotto's authorship of some parts of the last scenes is often questioned, and in the case of those in the last bay (after No. 25, usually attributed to the Saint Cecilia Master) denied completely.

This rather damaged scene was executed mainly by assistants.

Giotto's authorship of some parts of the last scenes is often questioned, and in the case of those in the last bay (after No. 25, usually attributed to the Saint Cecilia Master) denied completely.

Giotto's authorship of some parts of the last scenes is often questioned, and in the case of those in the last bay (after No. 25, usually attributed to the Saint Cecilia Master) denied completely.

Giotto's authorship of some parts of the last scenes is often questioned, and in the case of those in the last bay (after No. 25, usually attributed to the Saint Cecilia Master) denied completely.

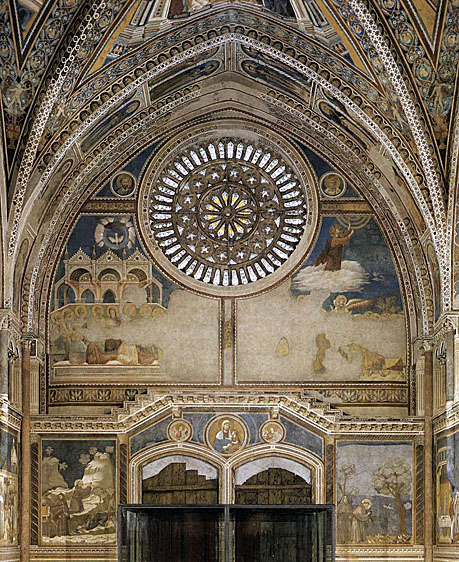

On the south wall of the nave and on the entrance wall episodes from the New Testament are painted above the Legend of Saint Francis occupying the lower part of the wall. Some of these scenes are attributed to Giotto. However, this observation is rejected by many scholars.

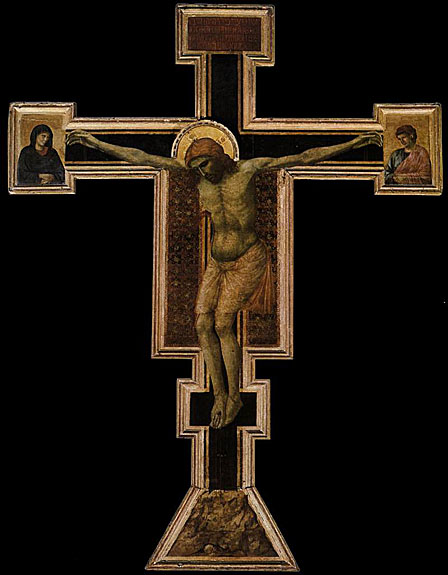

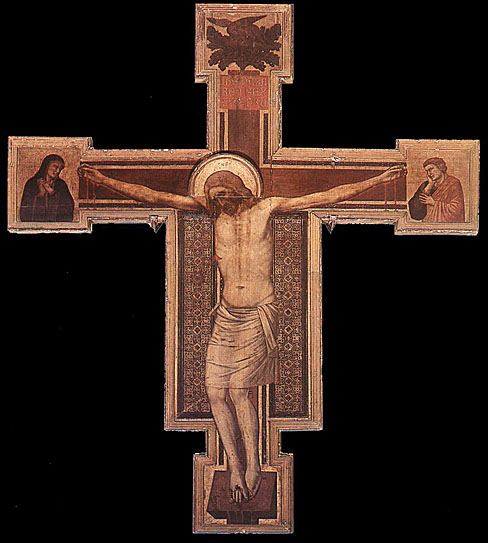

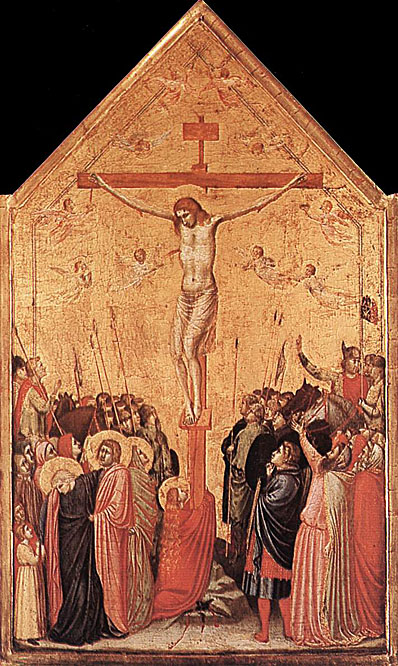

According to Vasari, Giotto's earliest works were for the Dominicans at Santa Maria Novella. These include a fresco of the Annunciation and the enormous suspended Crucifix which is about 5 meters high. It has been dated around 1290 and is therefore contemporary with the Assisi frescoes.

Other early works are the Madonna and Child panel now in the Diocesan Museum of Santo Stefano al Ponte, Florence, and the signed panel of the Stigmata of St. Francis, from Pisa and now in the Louvre.

This, probably Giotto's earliest surviving work, is the largest and most ambitious of the shaped panels of Christ on the cross painted by Giotto. Although his limited anatomical knowledge prevented him attaining the realism of his later crucifixes (In Padua and Rimini), Giotto's break with Byzantine tradition is clear. This can be seen from the natural pose, the sense of real weight in the way Christ's body so painfully hangs, the basic simplicity of the loin-cloth, and the realism of the two feet fixed with a single nail.

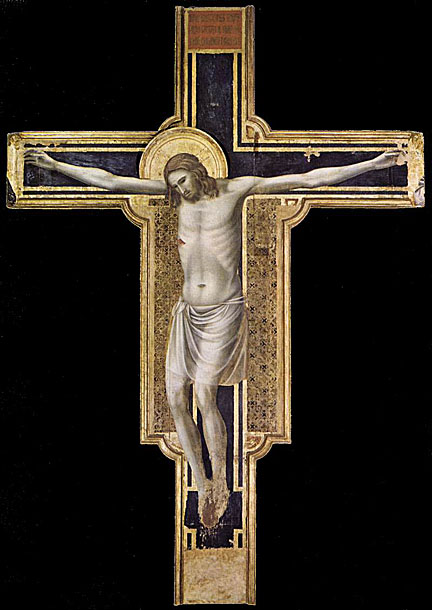

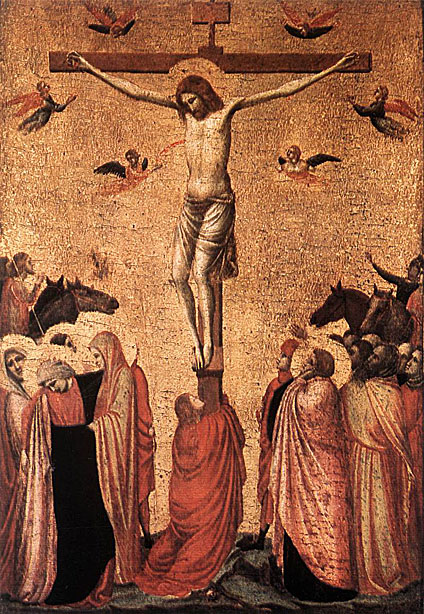

This painting is a nobler version of the Santa Maria Novella Crucifix (also better preserved), already showing tendencies of the artist's mature treatment of the subject.

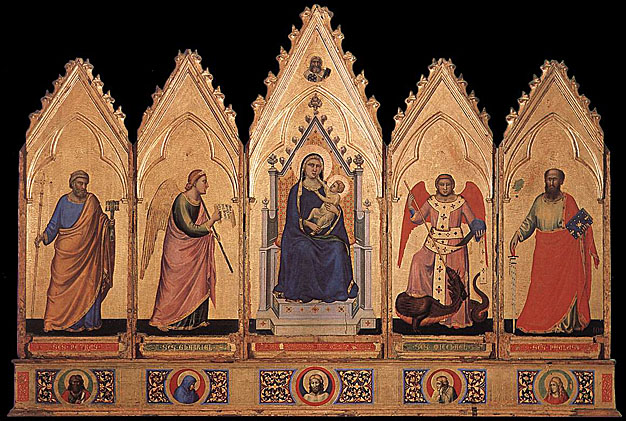

In 1287, at the age of about 20, Giotto married Ricevuta di Lapo del Pela, known as "Ciuta". The couple had numerous children, (perhaps as many as eight) one of whom, Francesco, became a painter. Giotto worked in Rome in 1297-1300, but few traces of his presence there remain today. The Basilica of San Giovanni in Laterano houses a small portion of a fresco cycle, painted for the Jubilee of 1300 called by Boniface VIII. In this period he also painted the Badia Polyptych, now in the Uffizi, Florence.

Giotto's fame as a painter spread. He was called to work in Padua, and also in Rimini, where today only a Crucifix remains in the Church of St. Francis, painted before 1309. This work influenced the rise of the Riminese school of Giovanni and Pietro da Rimini. According to documents of 1301 and 1304, Giotto by this time possessed large estates in Florence, and it is probable that he was already leading a large workshop and receiving commissions from throughout Italy.

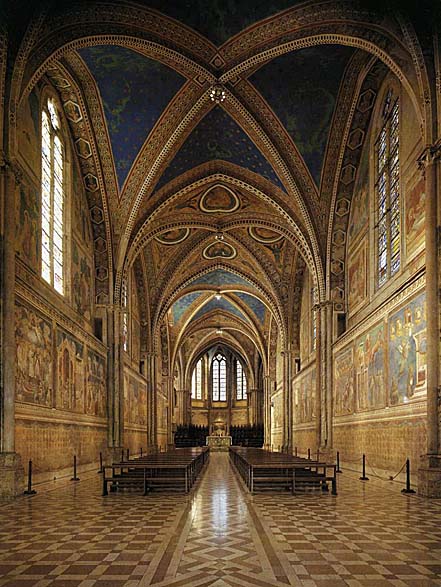

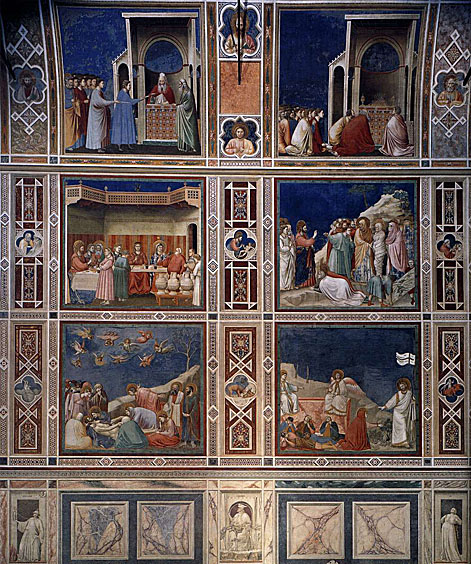

The Scrovegni Chapel Sometime between 1303 and 1310 Giotto executed (and signed) his most influential work, the painted decoration of the interior of the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua. This chapel, the building and decoration of which were commissioned by Enrico degli Scrovegni to atone for the sins of his father, is externally a very plain building of pink brick which was constructed next to an older palace that Scrovegni was restoring for himself. The palace, now gone, and the chapel were on the site of a Roman arena, for which reason it is commonly known as the Arena Chapel.

Enrico Scrovegni of Padua, ambitious son of the rich Reginaldo, whom Dante Alighieri had consigned to hell as a usurer in his "Divine Comedy", was planning to build a palace and a private chapel. To this end, in the year 1300, he purchased a large piece of land in the area around the Roman amphitheatre - known as the Arena. Of these impressive buildings, only the single-nave church remains. Constructed using clear, simple forms, it is referred to mostly as the "Arena Chapel" after its location, or as the "Scrovegni Chapel" after its donor. The redemption of his father and the saving of his own soul were his foremost considerations when making this donation. The church was therefore dedicated on 16 March 1305 to Saint Mary of Charity.

Today, it is Giotto's frescoes in the interior of the chapel which reflect the honor of the donor most of all, and it is the fact that he is portrayed on the side of the Blessed at the Last Judgment that has recorded his face for posterity.

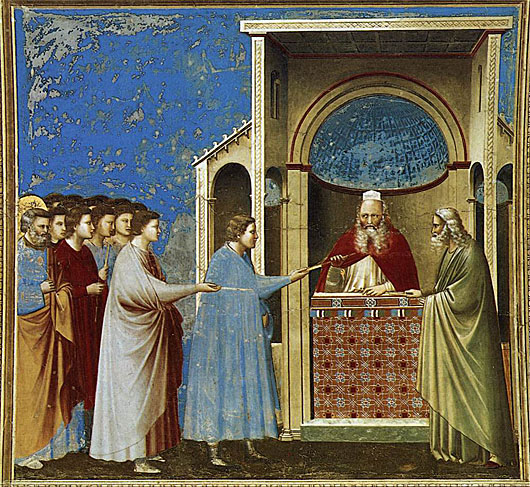

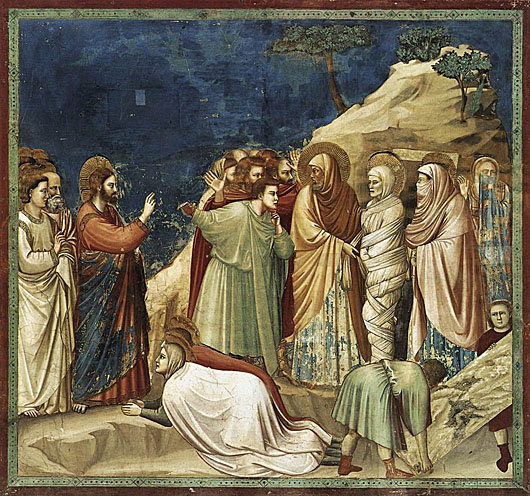

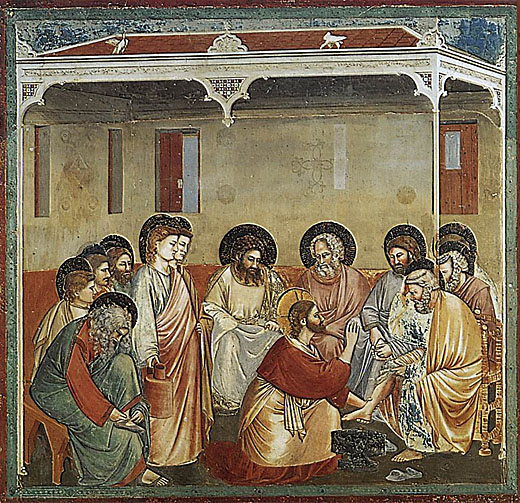

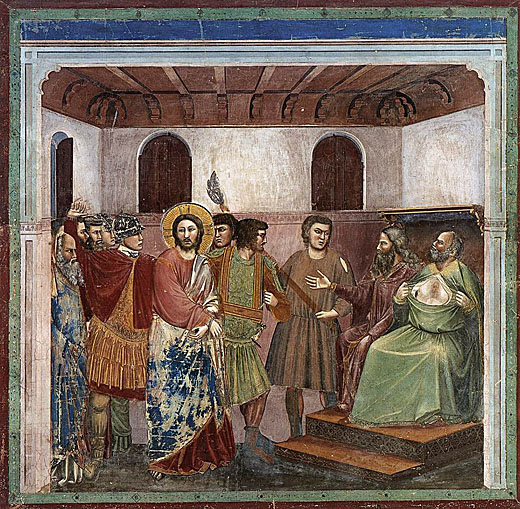

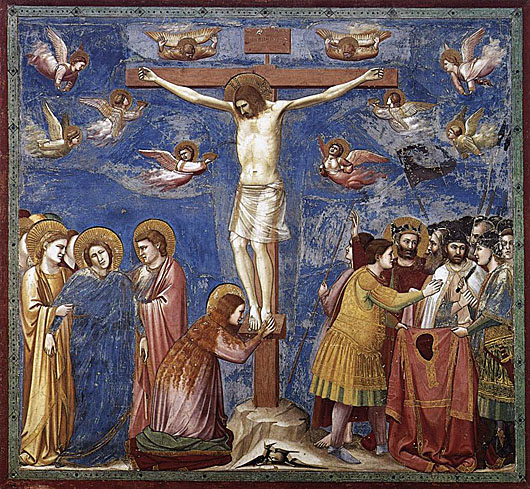

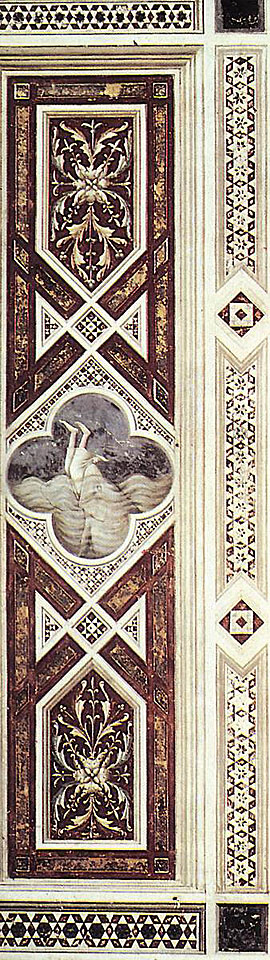

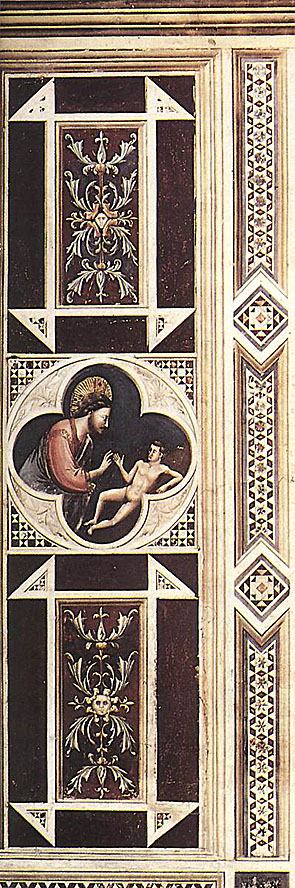

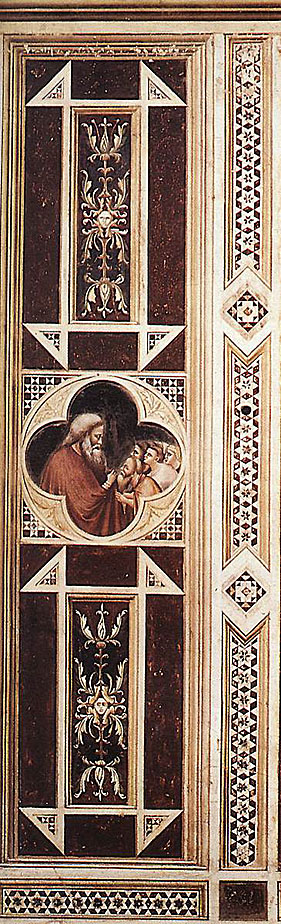

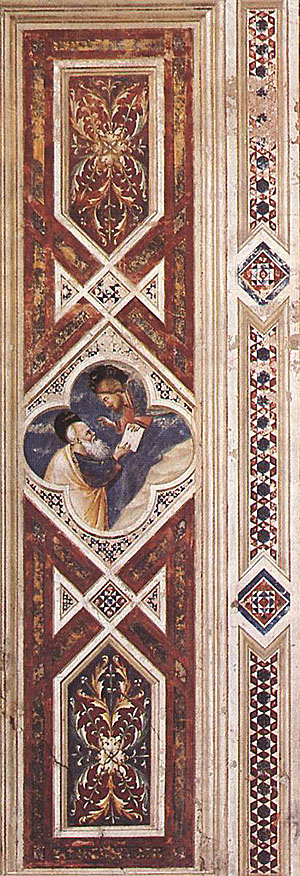

Vaulted by a starry sky with the two centers of Christ and Mary, the Last Judgment in the west and the Annunciation in the east, witnessed by God, frame the nave of the church. In between the two, the story of Mary is narrated on the upper register of the walls - beginning with scenes from the lives of her parents, Joachim and Anne - and the youth of Christ and the story of his Passion are narrated on the two lower registers. To a great extent the representations follow the "Legenda aurea", a collection of legends of the saints, written by Jacobus da Voragine in 1264. The narrative cycles rest on a painted dado. This complements the pictorial program, and proves to be one of the inventions with which Giotto renewed art, even in what is supposed to be only a secondary setting.

Giotto and his assistants painted from top to bottom. Since the painting was executed alfresco, moist plaster had to be applied only to a surface of sufficient size to be decorated in one day. We can assume that preliminary drawings were made for individual picture fields, so that Giotto could leave the execution of the secondary figures, the backgrounds and the decorative bands to members of his workshop. Without assistants and specialists, it would not have been possible to realize such an extensive decorative program in the short space of two to three years. Even if expert art historians believe they can identify individual assistants on the basis of stylistic characteristics, both in Padua and in the later frescoes for the Lower Church at Assisi and the Florentine church of Santa Croce, each of these paintings nevertheless appears as a unified whole, showing the hand of the master and bearing the stamp of his talent for invention.

The frescoes in the Arena Chapel have always been considered as Giotto's first mature masterpiece, and at the same time as an important milestone in the development of western painting.

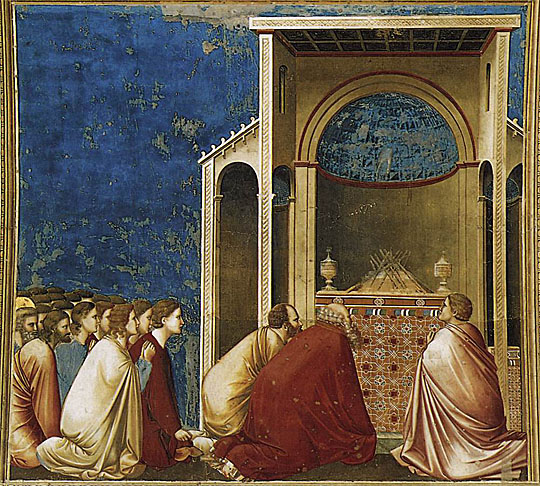

The individual scenes are composed in such a way that each stands as a picture in its own right, and yet each contains an impetus which passes from story to story in succession. Thus the narrative begins at the top left-hand of the south wall with the first scene from the life of Joachim, the Rejection of Joachim's Sacrifice.

The rejection of Joachim's sacrifice and his expulsion from the Temple occurred because of his childlessness. Here we are dealing with a true opening picture: the closed architecture of the temple introduces the first idea of solidity, while Joachim's dual movement brings this scene to a close, on the one hand, and on the other paves the way for the rest of the series, which finds a premature conclusion in the last picture of this register, the Meeting at the Golden Gate.

The action is also driven forward by the repetition of buildings. Thus the temple of the opening picture reappears in the fresco Presentation of Christ at the Temple.

Giotto's tendency to depict human figures almost as geometrical shapes is demonstrated by the way the sleeping figure of Joachim seems contained as if within a cube. The stillness of the scene is broken by the liveliness of the sheep. Here Giotto was perhaps inspired by his legendary youth as a Tuscan shepherd boy.

Even the verticals of the architecture and the golden arch of the city gate respectively illustrate and mirror the way the couple lean towards one another. The two meet on a bridge, on the border between the outside world and the security of the city. They embrace with great tenderness and kiss one another. The way in which the volumes of the figures fuse underlines the tenderness of the moment, in which the faces also melt, as it were, into one another.

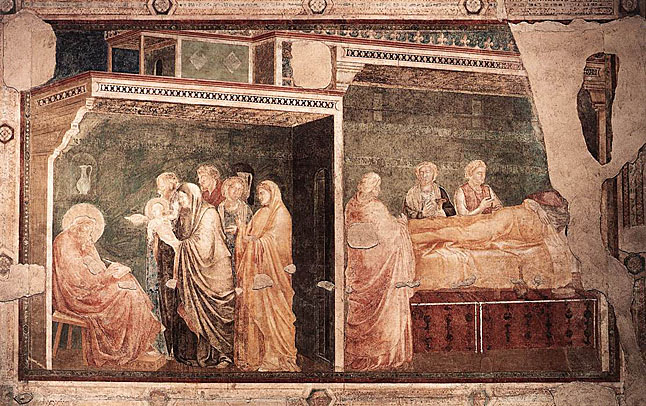

The story of Mary's parents begins with a painful rejection and concludes with this intense encounter. The sensitive portrayal of their meeting already contains the germ for the start of the next narrative, which commences with the Birth of the Virgin Mary and which leads to the youth of Christ by way of the Bridal Procession of the Virgin.

The theme is Salvation, and there is an emphasis on the Virgin Mary, as the chapel is dedicated to the Annunciation.

As is common in the decoration of the medieval period, the west wall is dominated by the Last Judgment. On either side of the chancel are complementary paintings of the Angel Gabriel and the Virgin Mary, depicting the Annunciation. This scene is incorporated into the cycles of The Life of the Blessed Virgin Mary and The Life of Christ. The source for The Life of the Virgin is the "Golden Legend" of Jacopo da Varazze while The Life of Christ draws upon "Meditations on the Life of Jesus" by the Pseudo-Bonaventura.

The cycle is divided into 37 scenes, arranged around the lateral walls in 3 tiers, starting in the upper register with the story of Joachim and Anna, the parents of the Virgin and continuing with the Story of Mary. The Life of Jesus occupies two registers. The Last Judgment fills the entire pictorial space of the counter-facade.

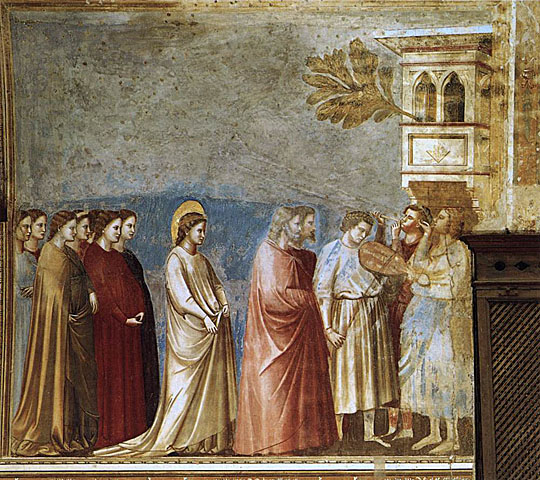

The story of Mary's parents concludes with their intense encounter at the Golden Gate. The sensitive portrayal of their meeting already contains the germ for the start of the next narrative, which commences with the Birth of the Virgin Mary and which leads to the youth of Christ by way of the Bridal Procession of the Virgin.

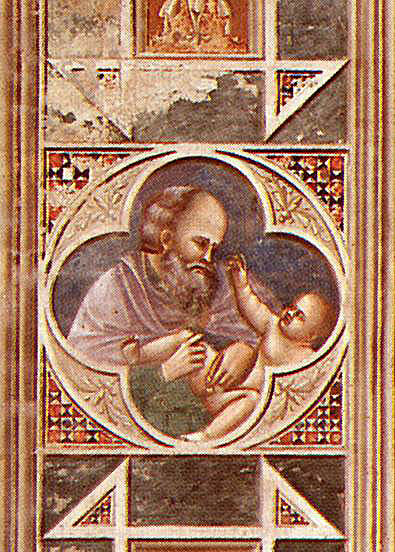

The birth of the Virgin takes place in the same house as the Annunciation to Anne. In the small room, somewhat too narrow for the figures, Anne sits up in bed and is handed the baby in its swaddling clothes by a nursemaid. The child appears for a second time in the idyllic scene in front of the mother's bed. As in the Annunciation scene, Giotto also shows the view of the building from outside. He does not divide interior and exterior, but connects them using the two women.

The three scenes related to the marriage of Mary take place in the same church.

The fresco was damaged by the humidity

The border between painted and real space appears to have been breached in Giotto's frescoes. This characterizes the representation of God the Father at the top of the triumphal arch wall above the entrance to the choir. The heavens have opened and ranks of angels surround God the Father on his throne. Among the angels, who move elegantly, the depiction of God, with his delicately shimmering, bright robes and his hieratic face, gives the impression of his belonging to a different sphere.

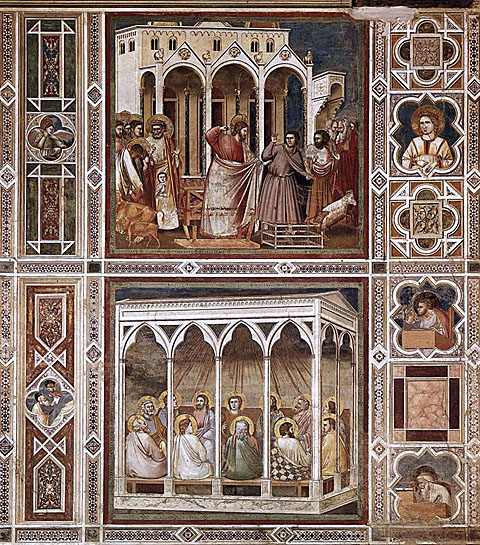

This particular effect is also the result of a different painting technique: God the Father is not painted as a fresco on the wall, but in tempera on a wooden panel. This "door" was presumably opened during the mystery plays performed to celebrate the Feast of the Annunciation, in order that the dove of Annunciation could fly out. The representation of the Annunciation directly below it is an indication of this. In a magnificent way, Giotto here combines the real architecture of the church interior with feigned, painted architectural elements to create a meaningful unity. To the right and left of the arch, the angel and Mary kneel in their respective buildings. It is only through the connecting architecture that tension is maintained within the depiction of the Annunciation, even over this great, daring distance and separation of figures, and that God the Father - at the top of the triumphal arch - is also included in the action. As far as form and content were concerned, Giotto was even here entering new territory.

The figure in the right was strongly damaged by the humidity.

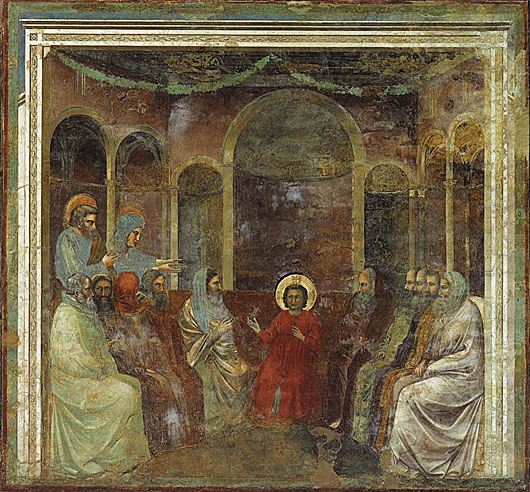

The youth of Christ and the story of his Passion are narrated on the two lower registers of the wall of the Scrovegni Chapel.

The temple in this scene is the same as that which appears in the Expulsion of Joachim from the Temple and the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple, but this time we are shown only the shrine over the altar.

Giotto (or a pupil of Giotto) painted this scene again in the Magdalen Chapel of the Lower Church of San Frencesco at Assisi in a larger version, using the same figures with similar attitudes.

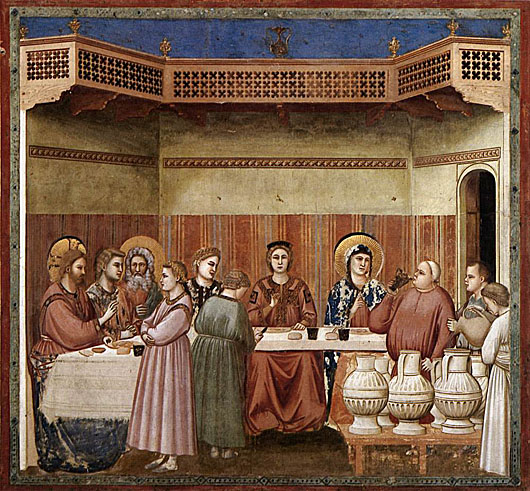

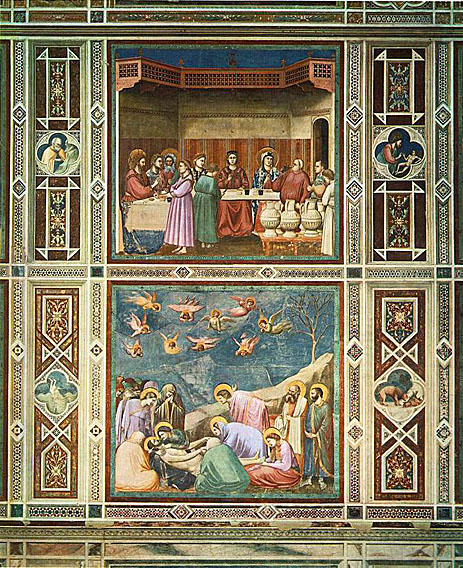

This scene is in the same setting as the Last Supper.

With the force of his body Judas presses against Christ, who appears to disappear beneath the traitor's cloak. This expresses the inevitable outcome of this overwhelming confrontation. Surrounded and hemmed in by numerous faces, the profiles of Christ and Judas almost collide. The two look at one another - the one with dignity and seriousness, the other full of malice. The whole drama of the event is captured in this infinitely long exchange of glances.

Some of the most dramatic parts in the Crucifixion and the following Lamentation are played by the small angelic spirits, who appear to have the lower part of their bodies hidden by clouds, a much more effective solution than that devised for the angelic spirits at Assisi, whose bodies are merely truncated. These small beings communicate their almost savage desperation through an extraordinary variety of attitudes and facial expressions not given to their human counter parts.

The chapel is entered from the west, the side on which the sun goes down. In accordance with an old tradition, the entrance wall of the chapel is filled by the depiction of the Last Judgment. This scene is as complex and crowded as the frescoes on the side walls are concentrated and reduced to essentials.

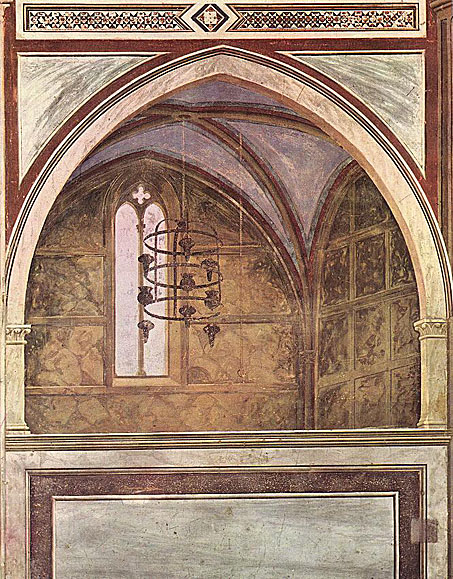

The way this large fresco is divided into registers is traditional. But if we look at Giotto's invention in detail, then his novel attempts at visualizing different spheres, as well as abstract beliefs, become particularly apparent. In the center of the representation, Christ is enthroned as supreme Judge in a rainbow-colored mandorla. The deep, radiant gold background, the style of painting and the delicate substance give the impression that the heavens have opened in order to reveal the powerful, extremely solidly modeled figure of Christ. Different levels are likewise alluded to when the choirs of angels disappear behind the real window, or when the celestial watch in the upper area of the picture rolls back the firmament, behind which the golden-red doors of the heavenly Jerusalem shine forth. The black and red maw of hell, which seems to anticipate Dante's "Inferno", is different again in its impact.

The way in which Giotto establishes a connection between the present-day world of the faithful and the world beyond all time, the world of the Last Judgment, contains another interesting detail. The donor Scrovegni, still alive at the time, kneels next to those being resurrected and offers "his" church to the three Marys, assisted by a priest. The latter is portrayed in a most lively manner: his robes hang - painted quite illusionistic - over the arch of the portal.

While Giotto's master Cimabue painted in a manner that is clearly Medieval, having aspects of both the Byzantine and the Gothic, Giotto's style draws on the solid and classicising sculpture of Arnolfo di Cambio. Unlike Cimabue and Duccio, Giotto's figures are not stylized, not elongated and do not follow set Byzantine models. They are solidly three-dimensional, have anatomy, faces and gestures that are based on close observation and are clothed, not in swirling formalized drapery, but in garments that hang naturally and have form and weight. Although aspects of this trend in painting had already appeared in Rome in the work of Pietro Cavallini, Giotto took it so much further that he set a new standard for representational painting.

The heavily sculptural figures occupy compressed settings with naturalistic elements, often using forced perspective devices so that they resemble stage sets. This similarity is increased by Giotto's careful arrangement of the figures in such a way that the viewer appears to have a particular place and even an involvement in many of the scenes. This dramatic immediacy was a new feature, which is also seen to some extent in the Upper Church at Assisi.

Famous panels in the series include the Adoration of the Magi, in which a comet-like Star of Bethlehem streaks across the sky, and the Flight from Egypt, in which Giotto broke many traditions in the depiction of the scene. The scenes from the Passion were much admired by artists of the Renaissance for their concentrated emotional and dramatic force, especially the Lamentation over the body of Christ, and studies of the sequence by Michelangelo exist.

The feature which more than any other sets Giotto's work apart from that of his contemporaries is his depiction of the human face and of human emotion in both expression and gesture. When the disgraced Joachim returns sadly to the hillside, the two young shepherds look sideways at each other. The soldier who drags a baby from its screaming mother does so with his head hunched into his shoulders and a look of shame on his face. The people on the road to Egypt gossip about Mary and Joseph as they go.

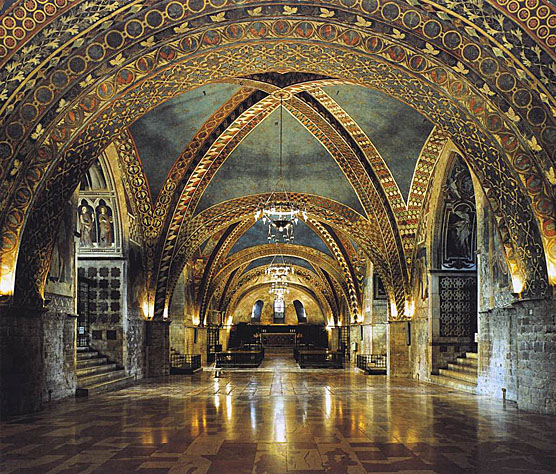

From 1306 to 1311 Giotto was in Assisi, where he painted frescoes in the transept area of the Lower Church, including The Life of Christ, Franciscan Allegories and the Maddalena Chapel, drawing on stories from the Golden Legend and including the portrait of bishop Teobaldo Pontano who commissioned the work. Several assistants are mentioned, including one Palerino di Guido. However, the style demonstrates developments from Giotto's work at Padua.

A new decoration of the lower church in Assisi was undertaken connected to the first centenary of the death of St Francis. Franciscan authors attribute the fresco cycle on the ceiling of the north transept to Giotto. However, this is not accepted by the majority of critics, they are thought to have been executed by collaborators and followers.

The fresco cycle on one side consists of large scenes from the life of the Virgin and the childhood of Christ separated by decorative bands with busts of Prophets, while the other side represents scenes from the Passion of Christ. The west wall is occupied by scenes representing the Miracle of St Francis in Sessa (in two parts) and the Annunciation.

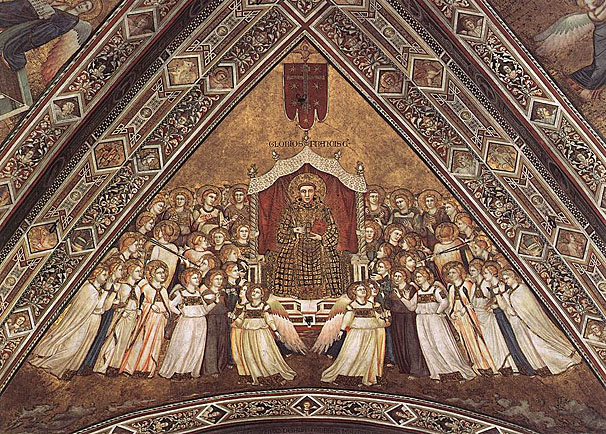

In the crossing vault of the Lower Church of San Francesco at Assisi, Giotto created an impressive culmination, both of the paintings there and of Franciscan iconography. Around the keystone with its representation of the Christ of the Apocalypse, the allegories of the three Franciscan virtues and St. Francis in Glory are painted in a radiant halo in the compartments of the vault.

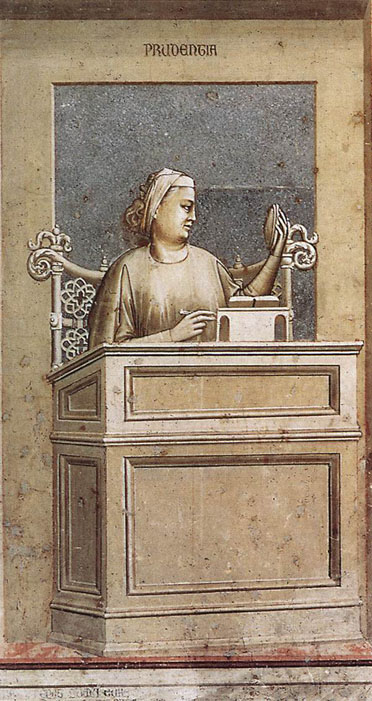

The embodiment of Presumptuousness, the horned centaur, is denied entrance. Two young men, a monk of the order and a layman, will follow in the footsteps of the saint. An angel has already taken one of them by hand. Interestingly, however, it seems to be Prudence who presides over such a decision: with her dual face she sees both past and future. She holds out a mirror, as a symbol of knowledge, towards the kneeling monk, whom the young men are following, and her astrolabe stands for the wider context which she is able to recognize.

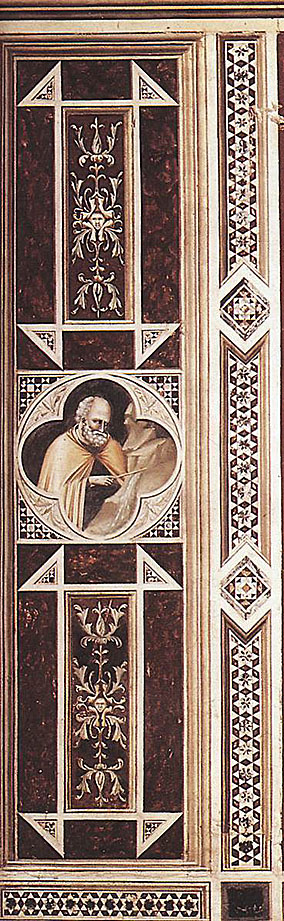

The Magdalene Chapel of the Lower Church is a lateral chapel in the corner between the northern transept and the nave. Its fresco decoration takes different forms: medallions with half-length figures, in the compartments of the vault, standing saints in the inside face of the entrance, narrative scenes on the walls and on the lunettes, and two portraits of donors on the end walls.

The authenticity and the dating of the frescoes in the Magdalen Chapel of the Lower Church of San Francesco is debated. It is generally agreed that they were executed with a contribution of Giotto but his role was probably that of planner rather than painter. There emerges the personality of one, or perhaps two of his assistants - the so-called Parente di Giotto and the Master of the Vele - who translated his ideas in their own style.

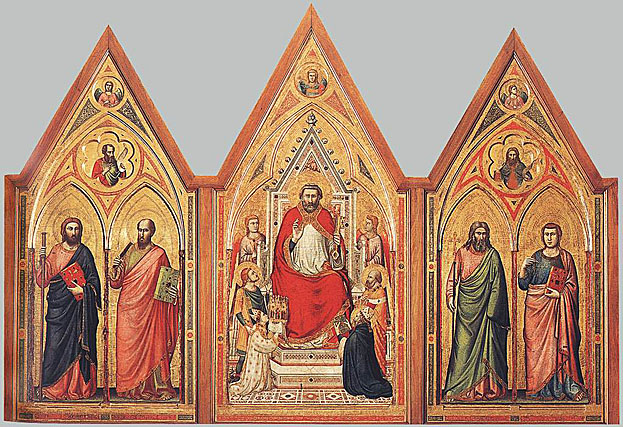

In 1311 Giotto returned to Florence, A document from 1313 shows his presence in Rome, where he executed a mosaic for the facade of the old St. Peter's Basilica, commissioned by Cardinal Jacopo Stefaneschi and now lost except for some fragments. In Florence, where documents from 1314-1327 attest to his financial activities, he painted an altarpiece known as the Ognissanti Madonna and now in the Uffizi where it is famously exhibited beside Cimabue's Santa Trinita Madonna and Duccio's Rucellai Madonna.

From the moment we look at the wooden panel painted in tempera we are fascinated by the gleaming solemnity of the paintwork. A fine web of golden edgings on the robes, of halos, and of decorative elements blends the golden hue of the background with the representation as a whole. Both the delicate shades of violet and pink, the warm green and red, and the flesh colors of the figures thus take on a brilliant luster, which allows the panel to shine with incomparable splendor.

Giotto turns to a type of picture known as the Maesta - the Madonna surrounded by saints and angels - which is especially well-known because of the Maesta by Duccio, begun in 1308, the one-time altarpiece of the cathedral at Siena, and through the great fresco in the Sienese Town Hall, completed by Simone Martini in 1315. These two examples of mature Sienese art have a relatively wide format: the numerous saints kneel and stand in rows to the left and right of the Virgin's throne. There they could be said to lead a "life of their own" - some look into the centre of the picture, others look at one another, and yet others direct their gaze out of the picture. Giotto's panel, on the other hand, is vertical in format and thus approaches the size and proportions of an older type of portrayal of the Madonna. This aspect is made particularly clear in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, where the Ognissanti Madonna is exhibited next to Duccio's Rucellai Madonna and the Madonna Santa Trinità by Cimabue, both of which were executed in the 1280s.

This representation of the Maesta, with its novel conception of the subject and its delicate style of painting, worked through with gold, numbers among the high points in Giotto's panel painting. Here, the natural portrayal and the solemnity of the mother and child are intensified in a special way. The clear perspective composition, in which the clearly directed gaze of the surrounding figures is included, makes the Child's gesture of benediction appear as the focal point, both optically and as regards content.

Restored in 1991

The exceptional vertical format of this panel, in which the towering rock narrows the scope of the action, is striking. The kneeling Saint seems startled and raises his hands. Christ appears to him, enveloped by angels' wings. The intense gaze between the two figures seems to allow the message that Francis has completely taken Christ to himself and then received the stigmata to take physical shape.

~Senex Magister

However, this is only my opinion.

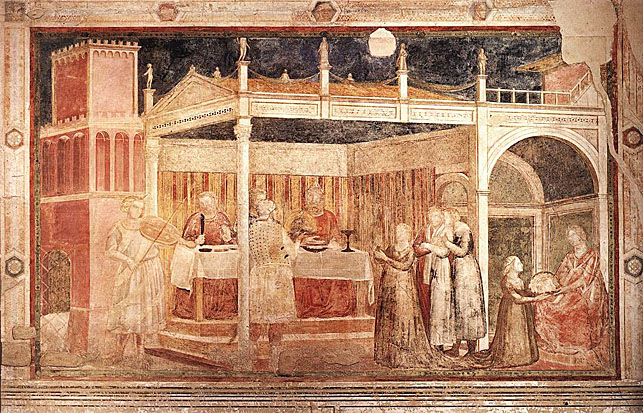

At this time he also painted the Dormition of the Virgin in the Berlin Gemaldegalerie and the Crucifix in the Church of Ognissanti. According to Lorenzo Ghiberti, in 1318 he began to paint chapels for four different Florentine families in the church of Santa Croce: the Bardi Chapel (Life of St. Francis), the Peruzzi Chapel (Life of St. John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist, including a polyptych of Madonna with Saints now in the Museum of Art of Raleigh, North Carolina) and the lost Giugni Chapel(Stories of the Apostles) and the Tosinghi Spinelli Chapel (Stories of the Holy Virgin). The remaining frescoes show that in later years Giotto's style had become more ornate, perhaps as a response to the emerging International Gothic style.

The Peruzzi Chapel was especially renowned during Renaissance times, and Michelangelo is known to have studied it. Though largely restored, the decoration displays clearly Giotto's capabilities in chiaroscuro and his study of perspective in the ancient buildings. Giotto's compositions later influenced Masaccio's Cappella Brancacci.

The Bardi Chapel is of particular interest as it follows the same iconographic plan as the frescoes in the Upper Church at Assisi, dating from about 20 years earlier. A comparison makes apparent the greater attention given by Giotto to expression in the human figures and the simpler, better integrated architectural forms.

As in the Peruzzi chapel, three frescoes framed by ornamental bands decorate each wall. But unlike in the former, these are dedicated to just the one saint, Saint Francis. The Renunciation of Worldly Goods and the Confirmation of the Rule are situated in the lunettes. In the middle register the Apparition at Arles and the Trial by Fire before the Sultan are depicted. The Death of Saint Francis and Inspection of the Stigmata and the Apparition at Aries can be seen at eye level. Above the entrance to the chapel the Stigmatization is portrayed, as it were, as a summation of the life of the saint. The seraphim from whom Francis receives the stigmata here appears - unlike at Assisi or in the panel in the Musee du Louvre - as the crucified Christ.

While the Saint Francis in the paintings in the Upper Church at Assisi wears a beard, Giotto depicts him without one here, as in the vault frescoes in the Lower Church. This manifestation of the Saint, favored by the order since 1316, must have been particularly agreeable to a banker, since it no longer expressed the original significance of personal poverty.

Unlike the Peruzzi Chapel, the construction of the architecture portrayed in the frescoes is here based on a viewpoint within the chapel. The perspective of the architectural structures in the paintings changes with great logical consistency - the higher the register, the greater the foreshortening from below. This only increases the impression of fluidity between real and painted space.

Being marked with the stigmata is the high point in the Saint's life. They mark him out for all to see as one of Christ's successors. The seraphim from whom Francis receives the stigmata here appears - unlike at Assisi or in the panel in the Musee du Louvre - as the crucified Christ. Fine golden rays emanating from Christ's wounds lead to St. Francis. In this representation the saint almost appears startled. He is in this way turned both towards the faithful and towards Christ.

The clearly articulated palace building is set obliquely within the field of the lunette. This creates great tension, appropriate to the confrontation between Saint Francis and his infuriated father. Giotto also uses the reactions of the individual figures to demonstrate the outrageousness of the saints public decision to renounce all his worldly goods.

The construction of the Peruzzi Chapel, the second chapel of the right-hand transept, was made possible by the influential banker, Donato di Arnoldo Peruzzi, who left additional money for this memorial chapel in his will in 1299. It was probably his grandson Giovanni di Rinieri Peruzzi who donated the murals honoring John the Evangelist and John the Baptist, which were the first works created by Giotto in Santa Croce.

The juxtaposition of the two John cycles is unusual, and researchers believe it contains a mixture of religious and secular iconography: John the Evangelist was the donor's name-saint; John the Baptist was patron saint both of the city of Florence and of Saint Francis, to whom Santa Croce is dedicated. In his family's memorial chapel the banker Peruzzi, therefore, has realized a program which connects his own memory and that of his family with the religious background of the Franciscans and the fate of the city, in which the Peruzzis were one of the most influential families.

Giotto has also further developed the depiction of space. Thus the buildings disappear behind the painted frame of the lunette, creating the impression that the view has been truncated.

Although thronged together, the people still display different reactions, which are obviously dependent on the distance they stand from the actual event, and which range from dumb amazement through to arms thrown up in horror.

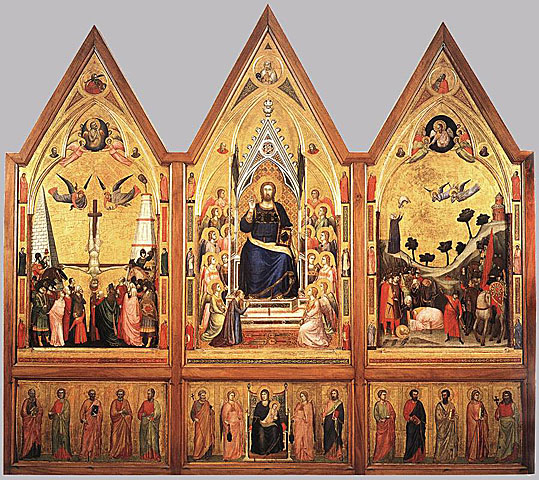

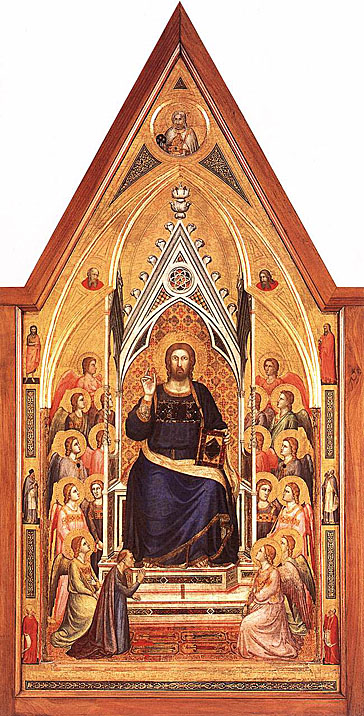

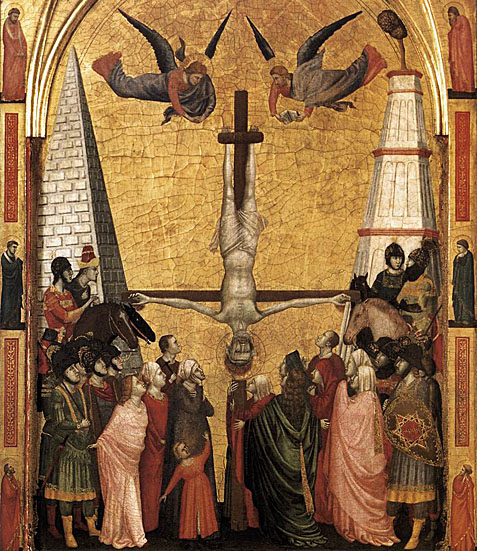

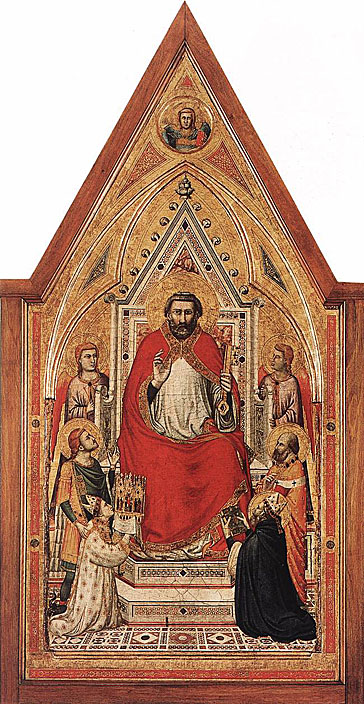

In 1320 Giotto finished the Stefaneschi Polyptych, now in the Vatican Museum, for Cardinal Jacopo, who also commissioned him the decoration of St. Peter's apse, with a cycle of frescoes destroyed during the 16th century renovation. According to Vasari, Giotto remained in Rome for six years, subsequently receiving numerous commissions in Italy and in the Papal seat at Avignon, though some of these works are now recognized to be by other artists.

The golden background and the rich coloring of the very delicate painting allow the side showing Christ to shine with particular splendor. Christ, delivering benediction, is enthroned in the center and surrounded by a host of angels. The representation of Virgin Mary and Child on the predella emphasizes the central axis of the altarpiece. Apostles surround Mary.

Surrounded by a heavenly host, the enormous Christ is enthroned in solemn majesty on a richly decorated Gothic throne. As if given a place among the circle of angels, the donor Cardinal Stefaneschi kneels before the throne on the marble floor, which is laid out in perspective. He is clothed in a simple robe and has reverently laid aside his cardinal's hat. Unlike the angels, the cardinal bends forward as if he wanted to kiss the feet of the Lord.

Peter has been nailed to the upside-down cross between a pyramid and the so-called Meta Romuli, the symbol of Rome and the Vatican. Soldiers and mourners throng towards the cross, while the Saint's soul is already departing. Exact observation - the Saint's hair hangs downward; sensitivity - a woman tenderly embraces the cross; and the most delicate brushwork - the green cloak of the figure with her back to us gleams sumptuously - characterize this composition.

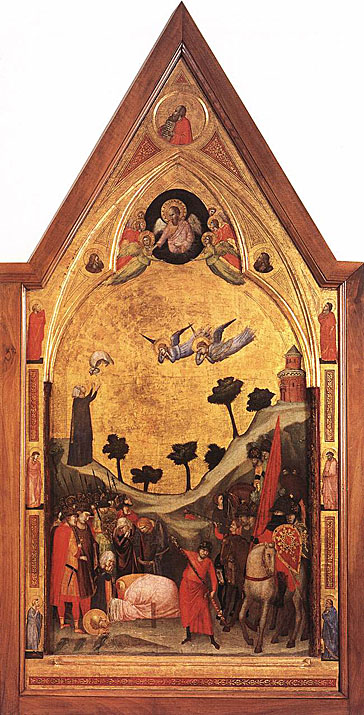

Against the golden background an amazingly deep landscape stretches out, representing the place where the Apostle Paul was beheaded: on the hill on the right we can recognize the lighthouse of Ostia. Opposite this tower, a maiden is thrown the cloth used to catch the saint's blood by his spirit. In the foreground, we see the executioner in the centre of the picture, separating the group of mourners around the beheaded man on one side, and the retreating soldiers on the other.

Peter sits, surrounded by angels and saints, on a simply constructed throne inlaid with Cosmati work. His right hand is raised in blessing, and in the other he holds the keys of his office. Before him, kneeling on the luxurious marble floor, laid out in perspective, are the 'Hermit-Saint Peter of Morrone' to his right, and the donor Cardinal Stefaneschi, offering him the altar, to his left.

In 1328, after completing the Baroncelli Polyptych, he was called by King Robert of Anjou to Naples, where he remained with a group of pupils until 1333. In Naples few of his works have survived: a fragment of a fresco portraying the Lamentation on the Dead Christ in the church of Santa Chiara, and the Illustrious Men painted on the windows of the Santa Barbara Chapel of Castel Nuovo (which are usually attributed to his pupils). In 1332 King Robert named him "first court painter" with a yearly pension.

Both the highly packed hosts of angels praising the Virgin and the huge figures in the central panel indicate that considerable assistance was needed for this work. Giotto no longer worked with a few individual assistants, but now had a well-organized studio. We are beginning to identify a number of Giotto's own relations and well-known artists.

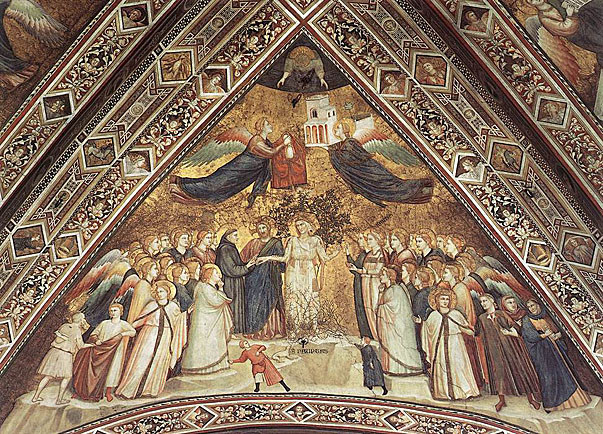

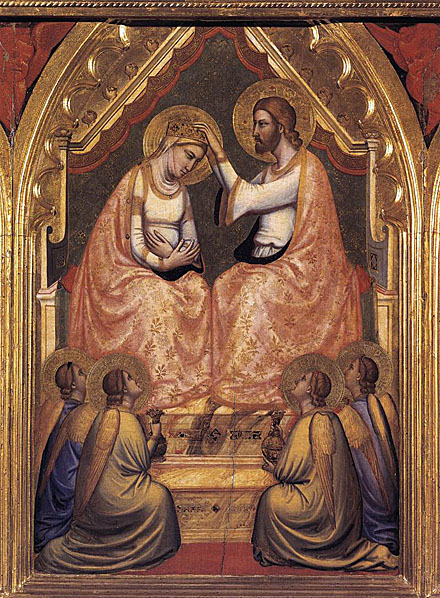

Mary and Christ sit on a broad throne. Mary bows her head reverently in order to receive the celestial crown from the hands of her Son. Mother and Son form a whole through their gestures, but mainly through their garments: both are clothed in radiant bright white and pink worked through with gold. The elegance of their clothing, in particular the trumpet-shaped sleeves on Christ's robe, indicates a great affinity with the style of courtly Gothic, a tendency which can also be observed in the frescoes in the Bardi Chapel.

After Naples Giotto stayed for while in Bologna, where he painted a Polyptych for the church of Santa Maria degli Angeli, and, according to the sources, a lost decoration for the Chapel in the Cardinal Legate's Castle.

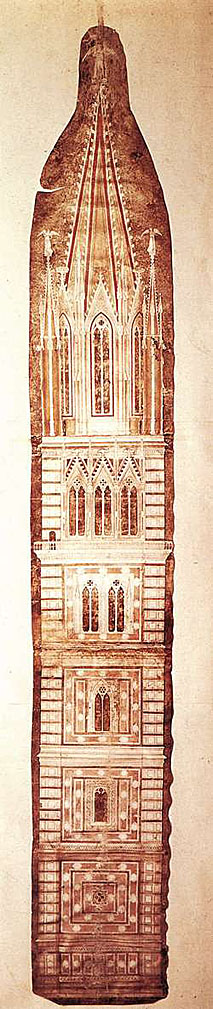

In 1334 Giotto was appointed chief architect to Florence Cathedral, of which the Campanile (founded by him on July 18, 1334) bears his name, but was not completed to his design.

After five years in Naples, Giotto returned to Florence. On 14 April 1334 the city appointed him Master of Municipal Construction Works and of the Cathedral Masons' Guild (capomaestro). Giotto performed this office for three years until his death. His attempts at architectural clarity and his interest in spatial conditions, such as the introduction of a unified viewpoint or the taking into consideration of different types of vaulting, could be found in every piece of painting by Giotto; even the decorative frameworks, which separated and linked the pictures, attest to his great feeling for architecture. So it is not really that remarkable that we find the artist at the end of his life as an architect.

In July 1334 the foundation stone of the campanile of the cathedral was laid - we can assume that the newly appointed capomaestro would have been given overall control of the building work. A sketch attributed to Giotto exists which allows us to see how close the design is to the painted architectural constructions and the frames of the altarpieces.

Only the lower story of the bell tower was realized from this design. There, set in the pink-colored fields of marble, are figural reliefs, whose order and number were changed by later alterations. The design of the original 21 reliefs very probably came from Giotto. They were executed by Andrea Pisano (1290-1348), Giotto's successor as capomaestro. A most original program is realized in these reliefs. They are divided into three groups of seven and dedicated to the theme of the creative.

Before 1337 he was in Milan with Azzone Visconti, though no trace of works by him remains in the city. His last known work (with assistants' help) is the decoration of Podesta Chapel in the Bargello, Florence.

In his final years Giotto had become friends with Boccaccio and Sacchetti, who featured him in their stories. In The Divine Comedy, Dante acknowledged the greatness of his living contemporary through the words of a painter in Purgatorio (XI, 94-96): "Cimabue believed that he held the field/In painting, and now Giotto has the cry,/ So the fame of the former is obscure."

Giotto died in January of 1337. According to Vasari, Giotto was buried in Santa Maria del Fiore, the Cathedral of Florence, on the left of the entrance and with the spot marked by a white marble plaque. According to other sources, he was buried in the Church of Santa Reparata. These apparently contradictory reports are explained by the fact that the remains of Santa Reparata lie directly beneath the Cathedral and the church continued in use while the construction of the cathedral was proceeding in the early 14th century.

During an excavation in the 1970's bones were discovered beneath the paving of Santa Reparata at a spot close to the location given by Vasari, but unmarked on either level. Forensic examination of the bones by anthropologist Francesco Mallegni and a team of experts in 2000 brought to light some facts that seemed to confirm that they were those of a painter, particularly the range of chemicals, including arsenic and lead, both commonly found in paint, that the bones had absorbed.

The bones were those of a very short man, of little over four feet tall, who may have suffered from a form of congenital dwarfism. This supports a tradition at the Church of Santa Croce that a dwarf who appears in one of the frescoes is a self portrait of Giotto. On the other hand, a man wearing a white hat who appears in the Last Judgment at Padua is also said to be a portrait of Giotto. The appearance of this man conflicts with the image in Santa Croce.

Vasari, drawing on a description by Boccaccio, who was a friend of Giotto, says of him that "there was no uglier man in the city of Florence" and indicates that his children were also plain in appearance. There is a story that Dante visited Giotto while he was painting the Arena Chapel and, seeing the artist's children underfoot asked how a man who painted such beautiful pictures could create such plain children, to which Giotto, who according to Vasari was always a wit, replied "I made them in the dark."

I am going to end my journey by returning the Arena Chapel and leave you with a Medieval view of the 'Seven Virtue and Vices' as depicted by Giotto.

Senex Magister

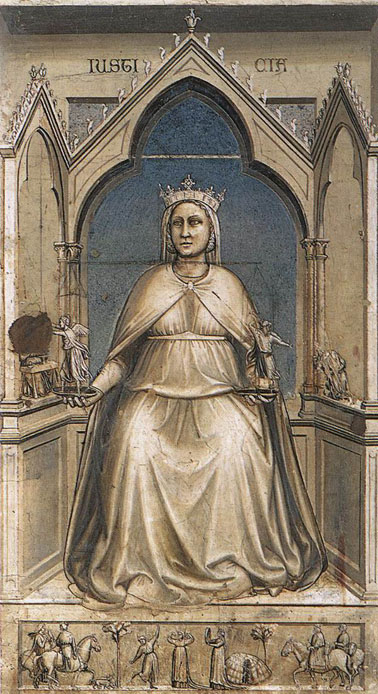

Among the multi-colored, painted marble slabs of the dado level, illusionistically depicted niches open up, in which Giotto has painted, as stone statues, the Virtues on one side of the chapel and the Vices on the other.

The canon of principal Christian virtues in the Middle Ages was made up of the three 'theological virtues' faith, hope and charity, and the four 'cardinal virtues', justice, prudence, fortitude and temperance. The cycle of seven virtues, sometimes paired with appropriate vices (not necessarily the seven Deadly Sins) was widely represented in medieval sculpture and fresco, often associated with the Last Judgment, like in the Scrovegni Chapel.

Justice (lustitia) is enthroned on a wide Gothic seat. She holds punishment and clemency on scales in her hands. Peaceful life develops under her reign - this is displayed in the scene on the pedestal other throne.

The cycle of seven virtues, sometimes paired with appropriate vices (not necessarily the seven Deadly Sins) was widely represented in medieval sculpture and fresco, often associated with the Last Judgment, like in the Scrovegni Chapel.

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.