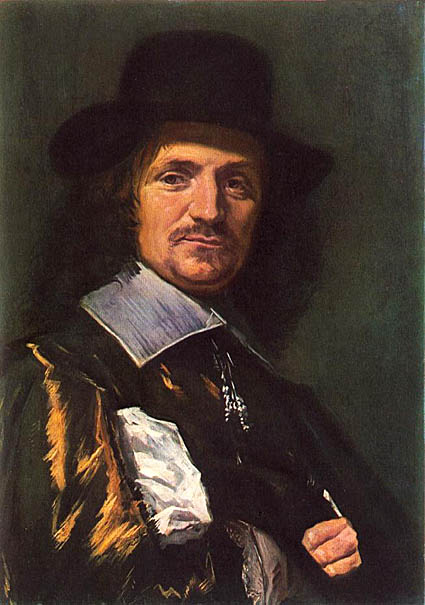

Netherlands Baroque Painter and Draftsman

1581 - 1666

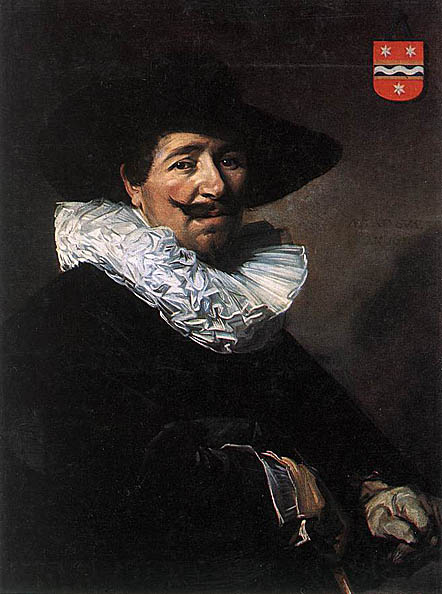

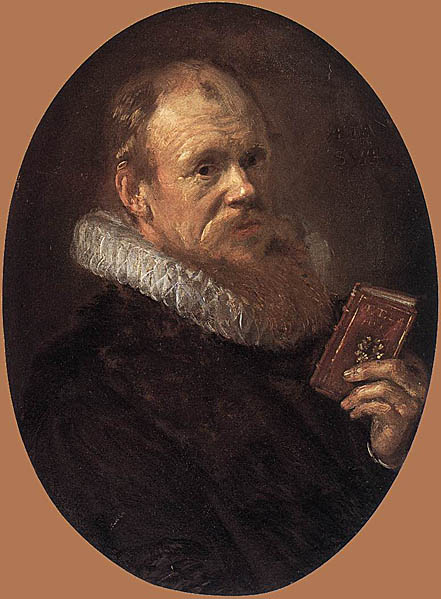

Frans Hals was a Dutch Golden Age painter especially famous for portraiture. He is notable for his loose painterly brushwork, and helped introduce this lively style of painting into Dutch art. Hals was also instrumental in the evolution of 17th century group portraiture.

Hals was born in 1580 or 1581, in Antwerp. Like many, Hals' family emigrated from the Spanish Netherlands to Haarlem In 1585-the year of the Fall of Antwerp-where he lived for the remainder of his life. Hals studied under another Flemish-emigre, Karel van Mander (1548-1606), whose Mannerist influence, however, is not noticeably visible in his work. Afterwards, at the age of 27, he became a member of the city's Guild of Saint Luke. The earliest known example of Hals' art is the 1611, Jacobus Zaffius. His 'breakthrough' came in 1616, with the life-size group portrait, The Banquet of the Officers of the Saint George Militia Company.

These civic guard portraits were an expression of the Baroque will to representation, whose tradition is rooted in the medieval era. There had been civic guards in the Netherlands since the 13th century. They had played an important role in the emancipation of the cities and towns from feudal rule and had gained considerable political and military significance in the Netherlands' struggle for independence.

Cornelis van Haarlem had already painted the officers of the Saint George Civic Guard in 1599. Hals, however, revolutionizes this type of painting. Instead of merely painting a row of individual portraits, he places them within a specific context by creating a banquet scene. This is not simply a moment captured at a table, but an extremely witty and calculated composition in which a scenic context is created between all the figures involved, and, on the other hand, each of the figures poses and acts independently and individually. Hals has found a new and persuasive solution to the problem of portraying a large group without difference of rank.

Hals seems to have arranged the officers casually around the festive board. But this is not the case. The places they occupy are in strict accord with military protocol. The colonel, the company's highest ranking officer, is seated at the head of the table; at his right is the provost, the second ranking officer. They are flanked by the company's three captains and the three lieutenants are at the lower end of the table. The three ensigns, who were not members of the officer corps, and the servant stand. Hals other group portraits of officers at banquet tables, which look equally informal, follow a similar hierarchical arrangement.

Historians have erroneously reported that he mistreated his first wife, Anneke Hermansz (Annetje Harmensdochter Abeel), based on records that a Frans Hals was charged with spousal abuse in Haarlem in 1616. However, as Seymour Slive has pointed out, the Frans Hals in question was not the artist, but another Haarlem resident of the same name. Indeed, at the time of these charges, the artist had no wife to mistreat as Anneke had died earlier in 1616. Similarly, historical accounts of Hals' propensity for drink have been largely based on embellished anecdotes of his early biographers, namely Arnold Houbraken, with no direct evidence existing documenting such. In 1617, already with two children by Anneke, he married Lysbeth Reyniers, with whom he had eight children.

Although Hals' work was in demand throughout his life, he experienced financial difficulties. In addition to painting, he worked as an art dealer and restorer. His creditors took him to court several times, and to settle his debt with a baker in 1652 he sold his belongings. The inventory of the property seized mentions only three mattresses and bolsters, an armoire, a table and five pictures. Left destitute, the municipality gave him an annuity of 200 forms in 1664.

At a time when the Dutch nation fought for independence, Hals appeared in the ranks of its military guilds. He was also a member of a local chamber of rhetoric, and in 1644 chairman of the Painters Corporation at Haarlem.

Frans Hals died in Haarlem in 1666 and was buried in the city's Saint Bavo Church. His widow later died obscurely in a hospital after seeking outdoor relief from the guardians of the poor.

Hals is best known for his portraits, mainly of wealthy citizens. He also painted large group portraits, many of which showed civil guards. He was a Baroque painter who practiced an intimate realism with a radically free approach. His pictures illustrate the various strata of society; banquets or meetings of officers, sharpshooters, guildsmen, admirals, generals, burgomasters, merchants, lawyers, and clerks, itinerant players and singers, gentlefolk, fishwives and tavern heroes.

Consider the smoked herring held in one hand by Pieter van der Morsch and the herrings he has in his straw basket in Frans Hals's portrait of him. At first blush his herrings appear to identify him as a fisherman or fishmonger hawking his wares. This seemingly convincing interpretation, which had been accepted since the portrait entered the literature in the nineteenth century, appears to be clinched by the conspicuous inscription: 'WIE BEGEERT' (Who Desires One). However, a close study of the seventeenth-century iconology of the smoked herring and of what could be learned about van der Morsch from contemporary sources demonstrated this interpretation is wrong. Van der Morsch was not a fisherman or fishmonger. He was a Leiden municipal court messenger who belonged to one of the city's literary societies where he played the part of a buffoon. A book of his own verse includes an epitaph he composed for himself. In it he characterizes himself as a man who distributes smoked herrings. Ample evidence establishes that in his time 'to give someone a smoked herring' (iemand een bokking geven) meant to shame someone with a sharp rebuke. The inscription on the painting is not a reference to the sale of smoked herrings. It refers to van der Morsch's readiness to ridicule. In Hals's painting the smoked herrings and inscription have been used to portray van der Morsch in his role as the wise fool of his literary society.

The double portrait is an excellent early example of Hals's subtle invention. The nurse, it seems, was about to present an apple to the young child when both were diverted by the approach of a spectator, to whom they appear to turn spontaneously, one of the many ingenious devices used by Hals to give the impression of a moment of life in his pictures. The color scheme still shows the dark tonality of his early commissioned portraits, and the minute execution of the child's richly embroidered costume is set off by a delightful vivacity in the brushwork on the faces and hands.

In 1635 Catharina became the teen-age bride of extremely wealthy Cornelis de Graeff who later served repeatedly as burgomaster of Amsterdam and became the city's guiding political force as well as adviser and confidant of Johan de Witt, Holland's leading statesman after the middle of the century.

In group portraits, such as the Archers of St. Hadrian, Hals captures each character in a different manner. The faces are not idealized and are clearly distinguishable, with their personalities revealed in a variety of poses and facial expressions.

The picture of 1639, in which Hals's self-portrait is to be seen, is the master's last representation of a civic guard group. The whole category virtually disappears in the Netherlands around the middle of the century. After the Treaty of Münster of 1648, which gave Holland de jure recognition in the councils of Europe, Dutch patricians preferred to be seen as dignified regents rather than military men.

He studied under the painter and historian Karel van Mander (Hals owned some paintings by van Mander that were amongst the items sold to pay his bakery debt in 1652). He soon improved upon the practice of the time, as exemplified by Jan van Scorel and Antonio Moro, and gradually emancipated himself from traditional portrait conventions.

Hals was fond of daylight and silvery sheen, while Rembrandt used golden glow effects based upon artificial contrasts of low light in immeasurable gloom. Both men were painters of touch, but of touch on different keys - Rembrandt was the bass, Hals the treble. Hals seized, with rare intuition, a moment in the life of his subjects. What nature displayed in that moment he reproduced thoroughly in a delicate scale of color, and with mastery over every form of expression. He became so clever that exact tone, light and shade, and modeling were obtained with a few marked and fluid strokes of the brush.

The only record of his work in the first decade of his independent activity is an engraving by Jan van de Velde copied from lost portrait of The Minister Johannes Bogardus. Early works by Hals, such as Two Boys Playing and Singing and a Banquet of the Officers of the Saint Joris Doele or Arquebusiers of St George (1616), show him as a careful draughtsman capable of great finish, yet spirited withal. The flesh he painted is pastose and burnished, less clear than it subsequently became. Later, he became more effective, displayed more freedom of hand, and a greater command of effect.

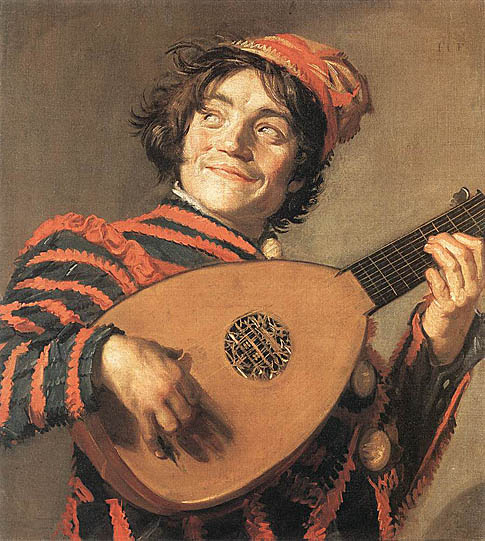

It seems certain that this painting represents Hearing from a series of allegories on the five senses. The other pieces may have been considered independent still-life paintings, and they have been scattered.

One additional detail seems to indicate that this painting is associated with the senses. The decorative feathered beret was not merely a fashionable dress item during the 1620s; its depiction may be interpreted as a symbol. "A feather on one's head indicates that one's sensitivities are as easily moved as the feather by the light breeze."

During this period he painted the full-length portrait of Madame van Beresteyn (Louvre), and a full-length portrait of Willem van Heythuysen leaning on a sword. Both these pictures are equaled by the other Banquet of the Officers of the Arquebusiers of Saint George (with different portraits) and the Banquet of the Officers of the Cloveniers or Arquebusiers of Saint Hadrian of 1627 and an Assembly of the Officers of the Arquebusiers of Saint Hadrian of 1633. A similar painting, with the date of 1637, suggests some study of Rembrandt masterpieces, and a similar influence is apparent in a picture of 1641 representing the Regents of the Company of Saint Elizabeth, and in the portrait of Maria Voogt at Amsterdam.

Even if nothing were known about van Heythuyzen's life there is no disputing it: Hals's portrait of him standing big as life captures the confidence and vitality of the burghers who made Holland the most powerful and richest nation in Europe during the first half of the seventeenth century. It is one of those rare pictures that seems to sum up an entire epoch. A sense of energy is conveyed by the tautness the artist gave to his model's bolt-upright figure. His extended leg does not dangle, but carries its full share of his weight. One arm just straight out, stiff as the sword he holds; the other makes a sharp angle from shoulder to elbow to hip, and even his knuckles take part in the taut, angular movement.

As in most of Hals's portraits of the 1620s, the light falls with equal intensity on van Heythuyzen's alert head and on his hands. Shiny highlights and sharp shadows heighten the subject's palpable presence and the blended brushstrokes that model flesh are set off by adjacent areas where there are distinct, detached touches of brush. No portraitist before Hals dared use such a variety of brushstrokes in a formal portrait. The Van Dyckian props, a rarity in Hals's oeuvre, are beautifully worked into the design. The vertical accent of the pilaster on the right reinforces the figure's erect carriage, and the burgundy drapery is incorporated into the pattern formed by van Heythuyzen's elephantine pair of bouffant knee-breeches and cloak cut like a cape.

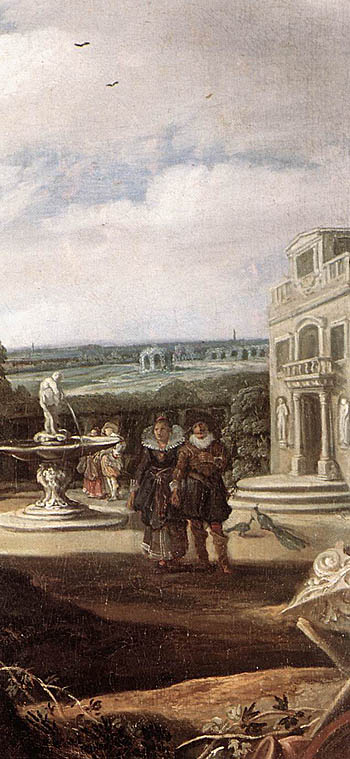

The prominent roses in this portrait of a man who remained a bachelor could allude, as they do so often in paintings of the period, to the pleasures and pain of love, references in van Mander's 'Schilderboek' suggest that they and the lovers in the garden in its background were probably intended as reminders of life's transience.

In both banquet pieces he links up two principal groups by long diagonals, and each single group shows a central seated figure, around which the other men are arranged, some seated and some standing. The crossing of the main diagonals coincides with the head of a seated figure in the second plane, which gains through this scheme and added interest and becomes a kind of occult centre. Ingenious variety of position and movement relates the figures to each other or to the spectator. The final result is an unprecedented illusion of an animated gathering.

The impression that these guardsmen could consume gargantuan quantities of food and liquor is confirmed by an ordinance laid down by the municipal authorities of Haarlem in 1621. Town official took cognizance of the fact that some of the banquets of the militia lasted a whole week. Considering that the municipality had to pay the costs, and that the times were troubled (the ordinance was written after hostilities with Spain had been resumed), it was decreed that the celebrations 'were not to last longer than three, or at the most four days...'

From 1620 till 1640 he painted many double portraits of married couples, on separate panels, the man on the left panel and his wife at his right. Only once did Hals portray a couple on a single canvas: Double Portrait of a Couple, (ca. 1622, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam).

Frans Hals's work for this bourgeois couple included an Italian landscape background on the right - a sunlit villa, marble statue and spring - whose purpose was to create the impression of elevated rank and dignified elegance. However, the background features are fanciful, bearing no relation whatsoever to the real world of the couple. Rather than the couple's country residence, scrutiny of iconographical details shows the villa to be the temple of Juno, the goddess of marriage, whose attribute was the peacock.

His style changed throughout his life. Paintings of vivid color were gradually replaced by pieces where one color dominated. After 1641 he showed a tendency to restrict the gamut of his palette, and to suggest color rather than express it. Later in his life darker tones, even with much black, took over. His brush strokes became looser in later years, fine detail becoming less important than the overall impression. Where his earlier pieces radiated gaiety and liveliness, his later portraits emphasized the stature and dignity of the people portrayed. This austerity is displayed in Regentesses of the Old Men's Alms House and The Regents and Regentesses of the Oudemannenhuis (ca. 1664), which are masterpieces of color, though in substance all but monochromes. His restricted palette is particularly noticeable in his flesh tints, which from year to year became more grey, until finally the shadows were painted in almost absolute black, as in the Tymane Oosdorp.

There is an old legend that Hals reduced to poverty in his last years and an inmate of the Alms House took his revenge on the Regents by depicting them in unflattering fashion. In fact, although he was certainly poor, he was never in the Alms House and the bold, free and animated style of the group is also evident in his other portraits of this period. It has been convincingly argued that the unusual expression on the face of the Regent who is seated on the right is the consequence of partial facial paralysis rather than - as the legend has it - drunkenness. Such candor is characteristic of Hals who felt no need to disguise the Regent's affliction. The standing figure, without a hat, is the servant of the Regents.

These two group portraits, painted at the very end of Hals's long career, display the remarkable shorthand that he (and other great painters in old age) discovered. No brushstroke is out of place or extraneous: there is no unimportant description of detail but a concentration upon essentials, the evocation of character in a few unerringly placed brushstrokes.

Whereas Hals previously presented individual gestures, attitudes and poses in a ceremonial and more than momentary context, here he isolates the individual parts and the individuals themselves. The faces above the white collars seem to float against the dark ground of a room that is difficult to distinguish. The "breakdown" of the figurative corresponds to the brushwork whose ductus is no longer fluid, but broken so that it seems to crumble into particles of color. Here and there, a shimmer of red flares up through the black like the final glimmer of dying embers in the ashes.

Whereas the iconography of vanitas and the theme of transience were previously expressed through specific symbols in Dutch painting, we now find that the most vigorous genre of the entire group portrait - has also been imbued with the concept of mortality. Old age and death seem to menace, where once there was activity and sociability.

As this tendency coincides with the period of his poverty, some historians have suggested that a reason for his predilection for black and white pigment was the low price of these colors as compared with the costly lakes and carmines.

As a portrait painter Hals had scarcely the psychological insight of a Rembrandt or Velazquez, though in a few works, like the Admiral de Ruyter, the Jacob Olycan, and the Albert van der Meer paintings, he reveals a searching analysis of character which has little in common with the instantaneous expression of his so-called character portraits. In these, he generally sets upon the canvas the fleeting aspect of the various stages of merriment, from the subtle, half ironic smile that quivers round the lips of the curiously misnamed Laughing Cavalier to the imbecile grin of the Malle Babbe. To this group of pictures belong Baron Gustav Rothschilds Jester, the Bohemienne and the Fisher Boy, while the Portrait of the Artist with his Second Wife, and the somewhat confused group of the Beresteyn Family at the Louvre show a similar tendency. Far less scattered in arrangement than this Beresteyn group, and in every respect one of the most masterly of Hals' achievements is the group called The Painter and his Family, which was almost unknown until it appeared at the winter exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1906.

People often think that Hals 'threw' his works 'in one toss' (aus einem Guss) onto the canvas. Research of a technical and scientific nature has clarified that this impression is not correct. True, the odd work was largely put down without underdrawings or under painting ('alla prima'), but most of the works were created in successive layers, as was customary at that time. Sometimes a drawing was made with chalk or paint on top of a grey or pink undercoat, and was then more or less filled in, in stages. It does seem that Hals usually applied his under painting very loosely: he was a virtuoso from the beginning. This applies, of course, particularly to his somewhat later, mature works. Hals displayed tremendous daring, great courage and virtuosity, and had a great capacity to pull back his hands from the canvas, or panel, at the moment of the most telling statement. He didn't 'paint them to death', as many of his contemporaries did, in their great accuracy and diligence whether requested by their clients or not.

As early as the 17th century, people were struck by the vitality of Frans Hals' portraits. For example, Haarlem resident Theodorus Schrevelius noted that Hals' works reflected 'such power and life' that the painter 'seems to challenge nature with his brush'. Centuries later Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo: 'What a joy it is to see a Frans Hals, how different it is from the paintings - so many of them - where everything is carefully smoothed out in the same manner.' Hals chose not to give a smooth finish to his painting, as most of his contemporaries did, but mimicked the vitality of his subject by using smears, lines, spots, large patches of color and hardly any details.

It was not until the 19th century that his technique had followers, particularly among the Impressionists. Pieces such as The Regentesses of the Old Men's Alms House and the civic guard paintings demonstrate this technique to the fullest.

Hals' reputation waned after his death and for two centuries he was held in such poor esteem that some of his paintings, which are now among the proudest possessions of public galleries, were sold at auction for a few pounds or even shillings. The portrait of Johannes Acronius realized five shillings at the Enschede sale in 1786. The portrait of the man with the sword at the Liechtenstein gallery sold in 1800 for 4, 5s.

Starting at the middle of the 19th century his prestige rose again. With his rehabilitation in public esteem came the enormous rise in values, and, at the Secretan sale in 1889, the portrait of Pieter van de Broecke Danvers was bid up to 4,420, while in 1908 the National Gallery paid 25,000 for the large group from the collection of Lord Talbot de Malahide.

Hals' works have found their way to countless other cities all over the world and into museum collections. From the late 19th century, they were collected everywhere - from Antwerp to Toronto and from London to New York. Many of his paintings were then sold to American collectors, who appreciated his uncritical attitude towards wealth and status.

A primary collection of his work is displayed in the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem.

In spite of the borrowings from the Utrecht school, there are nevertheless distinct differences. The figure does not develop from the darkness towards the light, but is lit from behind. The trompe l'oeil effects, the foreshortened hand and the skull that almost seems to jut beyond the front of the pictorial plane, are all masterly devices in which illusion is less important than painterly wit.

With a mug or tankard in his left hand, the man looks back at the viewer, his head inclined and his expression a little woozy, a humorous evocation of the vice of intemperance. The dark make-up on the face indicates that the painter is depicting an actor in the role of Peeckelhaering, and the red and yellow of the costume had in fact since the 16th century been associated with the jester.

Frans Hals was commissioned to paint the portrait of Captain Reynier Reael and Lieutenant Cornelis Michielsz Blaeuw of the Amsterdam crossbowmen's guild together with their militiamen. He was to paint the piece in Amsterdam, where the members of the company lived. For Hals, who lived in Haarlem, this involved regular trips to the capital. In fact he was rarely to make the journey at all. In 1636, three years after receiving the commission, he had still only completed part of the painting. Eventually the militiamen took him to the task. In reply he responded, as the preserved documents state, that it had been agreed he would begin the portraits in Amsterdam and complete them in Haarlem. The representatives of the guild, however, claimed that they had even offered six guilders extra per portrait on the condition that Hals travels to Amsterdam to paint the men's bodies as well as their faces. Hals was to receive 66 guilders per person upon completion of the painting, a total of 1,056 guilders for the whole work. Despite the high rate, Hals could no longer be persuaded to make the journey to Amsterdam. He suggested that the unfinished work be brought to Haarlem, where he would complete the sitters' attire. Then he proposed to finish painting the faces, assuming that the militiamen did not object to travelling to Haarlem. By now the dispute had become so heated that the guild decided to ask another artist to complete the painting. The task fell to Pieter Codde, a strange choice since Codde's paintings were usually small and meticulous. Codde lived in Amsterdam, though, and may even have been a member of the militia company.

Frans Hals painted the general outlines of the composition and completed some of the faces and hands, but only the ensign on the left, with the shiny satin jacket, is entirely by his hand. Pieter Codde painted the costumes and the portraits which Hals failed to complete.

In 1634 van den Broecke published an account of his exotic career which presents a purposeful and straightforward man who was typical of the aggressive entrepreneurs who shaped the Dutch commercial empire. This portrait, with its thrusting and confident pose, gives a similar impression and it is not surprising to find that it was used, in the form of an engraving by Adriaen Matham, as the frontispiece of van den Broecke's book. Van den Broecke knew Frans Hals well, acting as a witness at the baptism of Hals's daughter, Susanna, in 1634. The second witness was one Adriaen Jacobsz., almost certainly the Adriaen Matham who engraved the portrait for van den Broecke's autobiography.

It has been assumed that the sitter is Nicolaes Tulp, the famous physician of Amsterdam.

He was, however, more devastating when appraising members of the younger generation who found themselves dissatisfied with their father's tastes, and began to imitate the manners and clothes of the French nobility. Yet the artist was able to satisfy the desire of young patrons for rich effects without losing his extraordinary sensitivity to tonal gradations as seen in his half-length of Jasper Schade, a patrician of Utrecht who later was representative of his province to the States-General.

Hals's characterization of him, and his firm control of pictorial organization, convinces us that as a young man his sitter was a vain, proud peacock, an impression confirmed by a contemporary report that he spent extravagant sums on his wardrobe. In a letter written in 1645 (almost certainly the date of Hals's portrait) his uncle admonished his son, then in Paris, not to run up tremendous bills with his tailors the way his cousin Jasper Schade had done.

A subtle emphasis on verticality in the portrait contributes to Jasper's haughty air - not that an emphasis on vertical forms express arrogance, but here it certainly does. His hat's upward turned brim and the straight arrangement of his long hair accent the length of the face of a man looking down at people below his station. And while thin, frail bodies may contain most noble spirits; this one hardly inspires confidence in its inner strength. As dazzling as Hals's appraisal of his sitter are the zigzag and angular brushstrokes that suggest the nervous dance of bright light on his grey taffeta jacket while creating an electrifying movement on the picture surface.

In Frans Hals' work we can see almost every type of portrait: full-length, half-length, group portraits, studies of heads. Background detail is almost non-existent, the pictures usually being of a summary simplicity with figures in dark clothes and neutral backgrounds. Interpretation of character and expression is the dominant feature, and by means of effective poses and masterly brushwork, made up of black and white and grey strokes, the artist expressed the essence of his sitter's personality. In most cases we do not even know who the sitters were, and it is only recently that the dashing figure in this picture has been identified as the painter Jan Asselyn.

After 1641, Frans Hals never again employ any positive or vivid color whatever in the accessories of his portraits, his flesh tones become much lower, and, above all, the flesh shadows duskier and tending to blackness. At first this last trait is not so strongly pronounced, but as we get farther onwards from the year 1641 the tendency increases, and in one or two extreme instances, such as the portrait of Tyman Oosdorp, flesh shadows are in places absolutely black.

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.