/>

Francisco de Goya

Disclaimer

Francisco Jose de Goya y Lucientes

Spanish Romatic Painter, Draftsman, and Printmaker

1746 - 1828

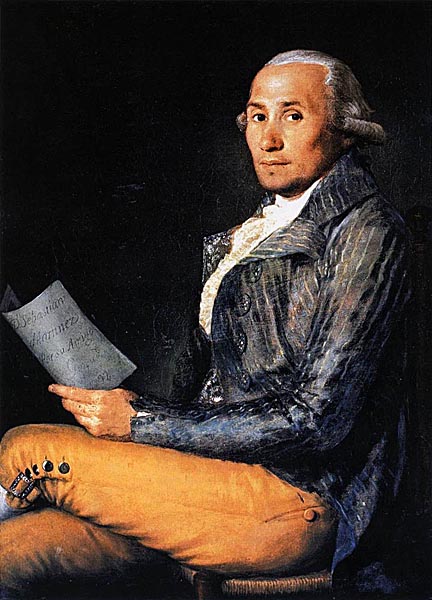

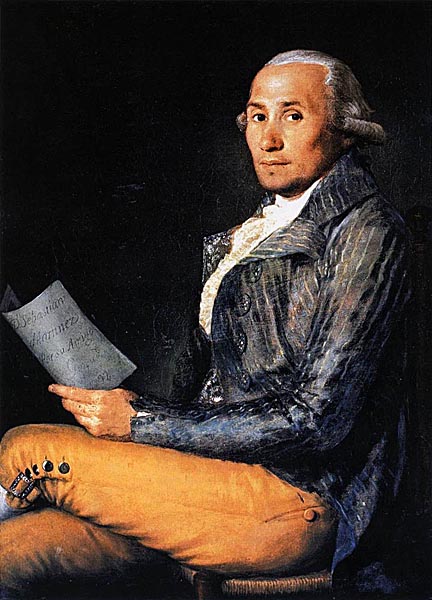

Self Portrait of Francisco de Goya

Francisco Jose de Goya y Lucientes was an Aragonese Spanish painter and printmaker. Goya was a court painter to the Spanish Crown and a chronicler of history. He has been regarded both as the last of the Old Masters and as the first of the moderns. The subversive and subjective element in his art, as well as his bold handling of paint, provided a model for the work of later generations of artists, notably Manet and Picasso.

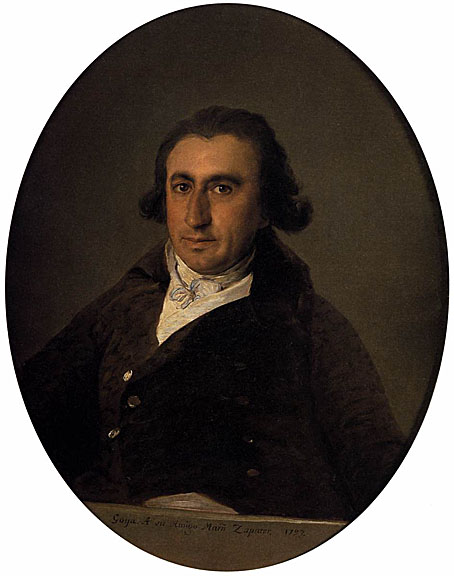

Goya was born in Fuendetodos, Spain, in the kingdom of Aragon in 1746 to José Benito de Goya y Franque and Gracia de Lucientes y Salvador. He spent his childhood in Fuendetodos, where his family lived in a house bearing the family crest of his mother. His father earned his living as a gilder. About 1749, the family bought a house in the city of Saragossa and some years later moved into it. Goya attended school at Escuelas Pias, where he formed a close friendship with Martin Zapater, and their correspondence over the years became valuable material for biographies of Goya. At age 14, he entered apprenticeship with the painter José Luján.

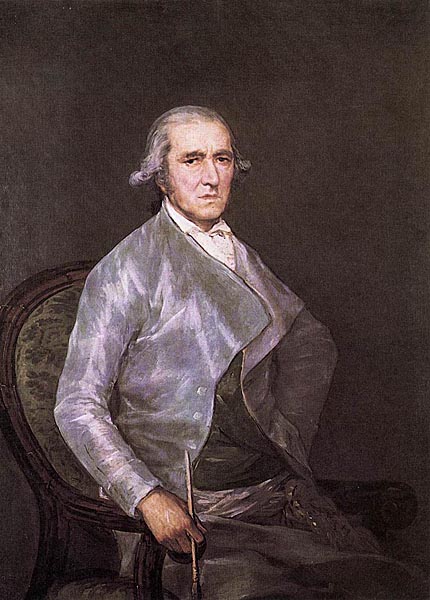

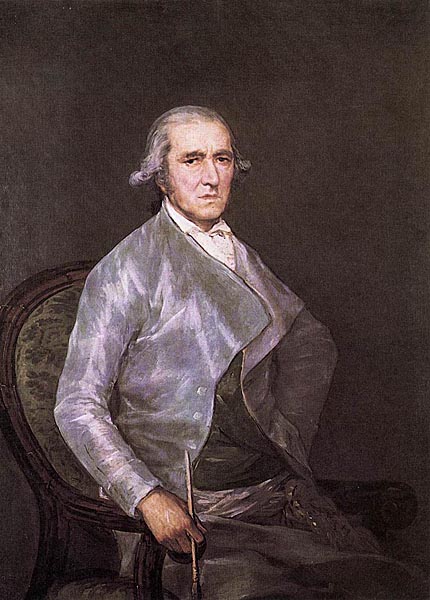

Anton Raphael Mengs

He later moved to Madrid where he studied with Anton Raphael Mengs, a painter who was popular with Spanish royalty. He clashed with his master, and his examinations were unsatisfactory. Goya submitted entries for the Royal Academy of Fine Art in 1763 and 1766, but was denied entrance.

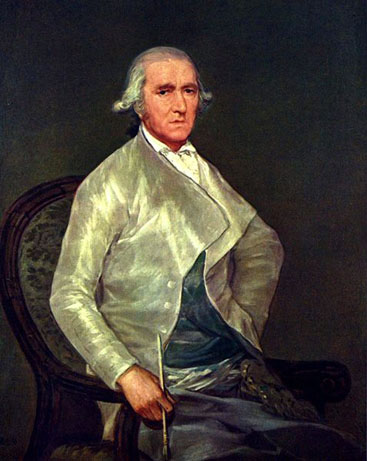

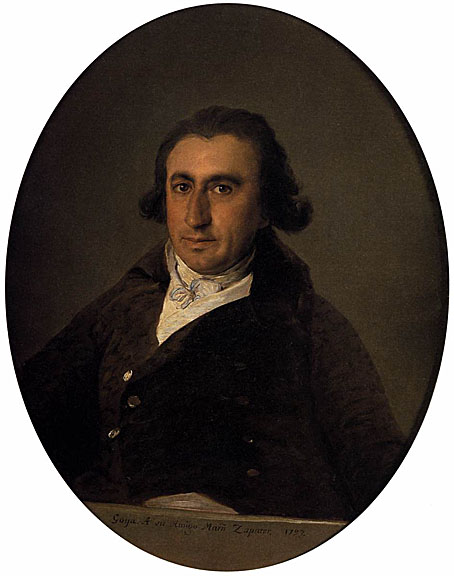

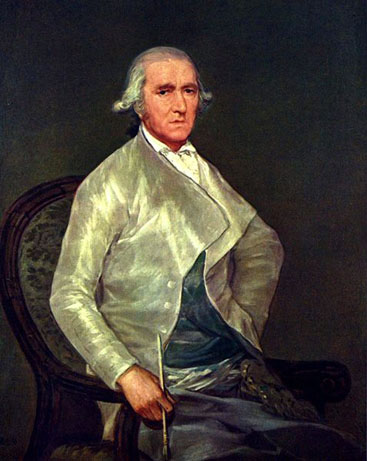

Francisco Bayeu

He then journeyed to Rome, where in 1771 he won second prize in a painting competition organized by the City of Parma. Later that year, he returned to Zaragoza and painted a part of the cupola of the Basilica of the Pillar, frescoes of the oratory of the cloisters of Aula Dei, and the frescoes of the Sobradiel Palace. He studied with Francisco Bayeu y Subías and his painting began to show signs of the delicate tonalities for which he became known.

Josefa Bayeu

Goya married Bayeu's sister Josefa in 1774. His marriage to Josefa (he nicknamed her "Pepa"), and Francisco Bayeu's membership of the Royal Academy of Fine Art (from the year 1765) helped him to procure work with the Royal Tapestry Workshop. There, over the course of five years, he designed some 42 patterns, many of which were used to decorate (and insulate) the bare stone walls of El Escorial and the Palacio Real de El Pardo, the newly built residences of the Spanish monarchs. This brought his artistic talents to the attention of the Spanish monarchs who later would give him access to the royal court. He also painted a canvas for the altar of the Church of San Francisco El Grande, which led to his appointment as a member of the Royal Academy of Fine Art.

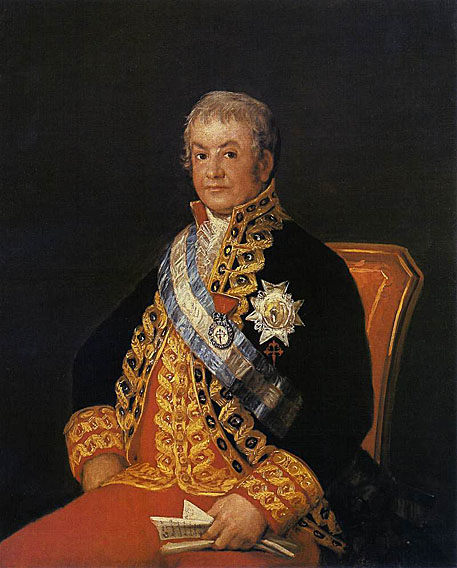

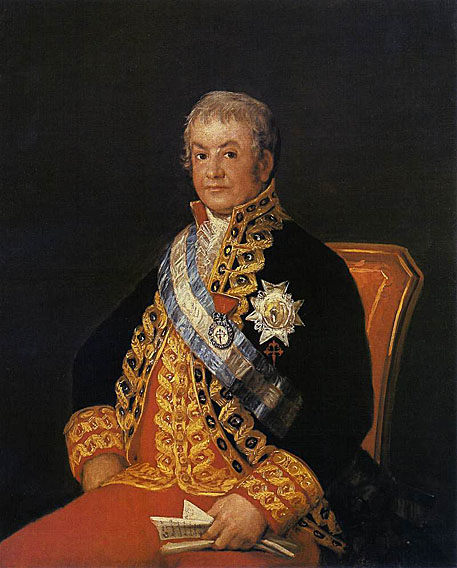

In 1783, the Count of Floridablanca, a favorite of King Carlos III, commissioned him to paint his portrait. He also became friends with Crown Prince Don Luis, and lived in his house. His circle of patrons grew to include the Duke and Duchess of Osuna, whom he painted, the King and other notable people of the kingdom.

Carlos III: 1786 - 88

Family of the Infante Don Luis: 1783

The brother of King Charles III - banished from court for marrying beneath him - commissioned this group portrait of his family and servants. It is evening, the master of the household is playing cards, while his wife is having her hair done.

The Family of the Duke of Osuna: 1788

This 'enlightened' couple, members of the upper aristocracy, were amongst the artist's most influential patrons. Pomp and status symbols are renounced in favor of a discreet idyll in a subdued palette of greys, browns and greens.

After the death of Charles III in 1788 and revolution in France in 1789, during the reign of Charles IV, Goya reached his peak of popularity with royalty.

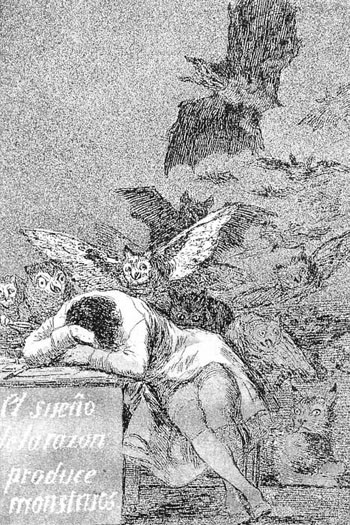

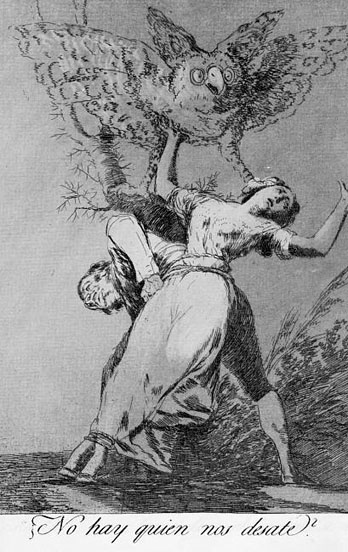

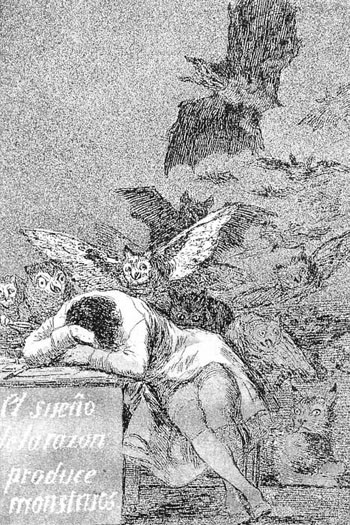

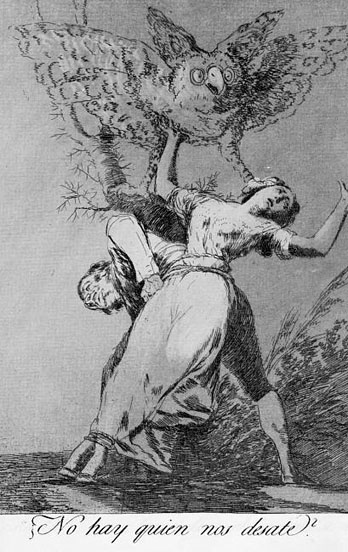

After contracting a high fever in 1792 Goya was left deaf, and he became withdrawn and introspective. During the five years he spent recuperating, he read a great deal about the French Revolution and its philosophy. The bitter series of aquatinted etchings that resulted were published in 1799 under the title Caprichos. The dark visions depicted in these prints are partly explained by his caption, "The sleep of reason produces monsters". Yet these are not solely bleak in nature and demonstrate the artist's sharp satirical wit, particularly evident in etchings such as Hunting for Teeth. Additionally, one can discern a thread of the macabre running through Goya's work, even in his earlier tapestry cartoons.

Francisco Goya y Lucientes Pintor

This is Plate 1 from the series of 80 etchings published in 1799 called Los Caprichos. In these the artist used the popular imagery of caricature in a highly original and inventive form for his first essay in the criticism of political, social and religious abuses, for which he is famous. His mastery of the recently developed technique of aquatint makes these etchings a major achievement in the history of engraving.

Caprichos

In Los Caprichos Goya experimented with the relatively recent technique of aquatint. This involved covering some parts of the metal plate used to produce the print with a porous resin, while ‘stopping out’ other parts (that is, preventing them from absorbing ink) by covering them with varnish. The stopped-out sections would finally appear white while the resin-covered section would absorb ink through tiny ‘holes’ between the grains of resin. In this way and through subsequent ‘bitings’ of the plate in an acid bath, soft, velvety and granular shaded areas would be produced. Thus, Goya was able to enhance the effects of etched lines (or drawing) through the addition of varied and expressive tonal effects. Half-tones could be created through the process of burnishing, in which a special tool is used to make flatter or smoothed-down areas of the plate which carry less ink than they would have done and hence produce lighter areas on the finished print.

They Say Yes and Give their Hand to the First Comer

They say yes and give their hand to the first one who comes: depicts a beautiful young girl being married off to a breathtakingly ugly older man. Rather than having sympathy for the girl, Goya, by quoting a line from a poem by Jovellanos in his caption, is suggesting that the girl is marrying the old, ugly man for his money alone. They are engaged in a "pantomime" in which both are completely complicit. The lustful older man gets his trophy bride while the young woman achieves financial security.

Even Thus he Cannot Make her Out

Again and again Goya targets assumptions that people make about relationships: between men and woman; elder and younger; clergy and congregation. While he attempts to expose the mercenary nature of marriage, he also addresses the cult of prostitution. In his “Ni así la distingue” (Even like this he can’t make her out), Goya shows what appear to be a well dressed man leaning in and viewing a beautiful young maja through a monocle.

According to Robert Hughes, once again Goya is highlighting the mutual deception being undertaken by the two protagonists. The prostitute must not immediately reveal that she is a prostitute since this would deflate the romantic illusion and possibly scare off her customer; the gentleman is also quite willing to suppress the truth since he is perfectly happy to maintain the pretence that a beautiful young woman is charmed by his company.

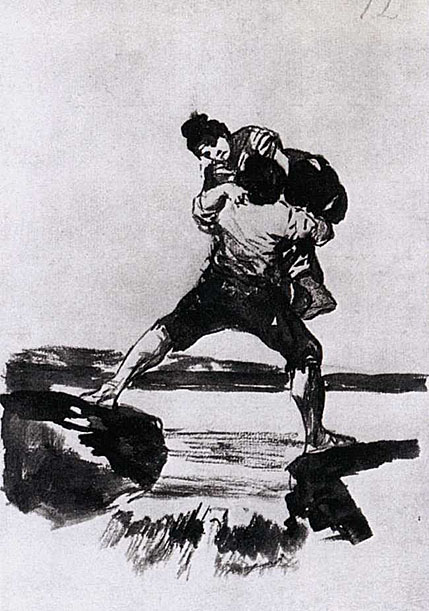

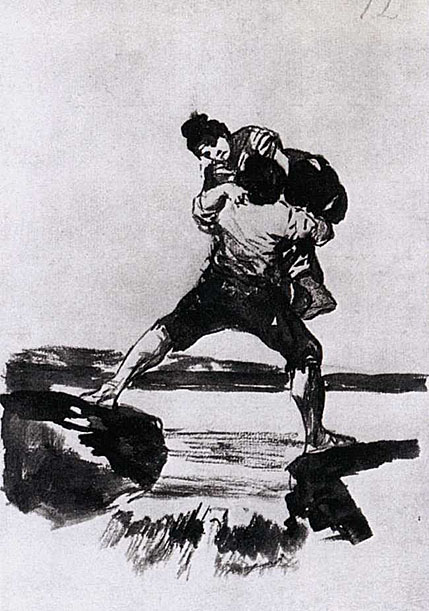

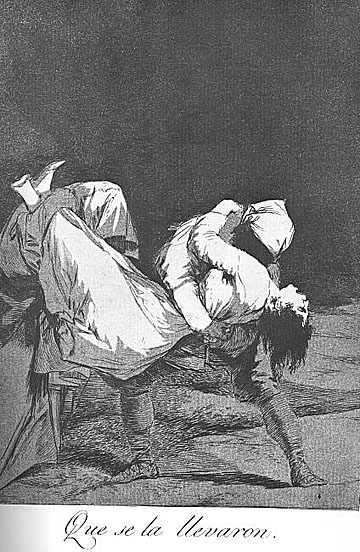

They Carried her Off

The plate is one of Goya's particularly forceful indictments against violence towards women. The perpetrators remain anonymous; the one at the back is wearing a monk's habit. Only the woman's head is rendered in detail.

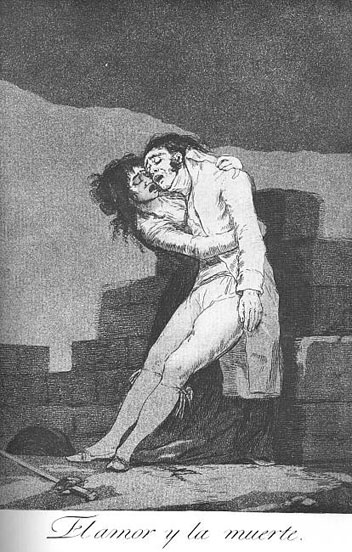

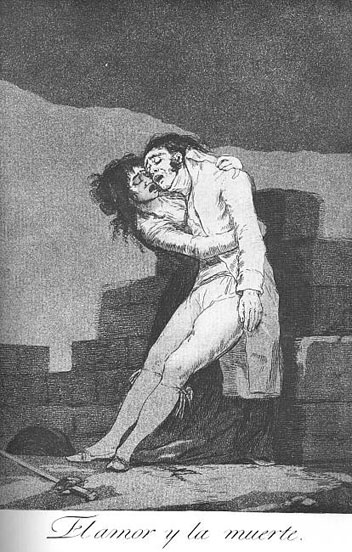

Love and Death

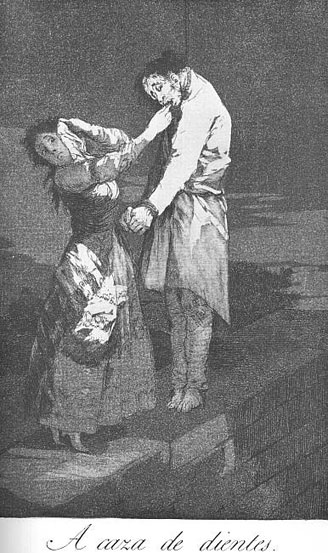

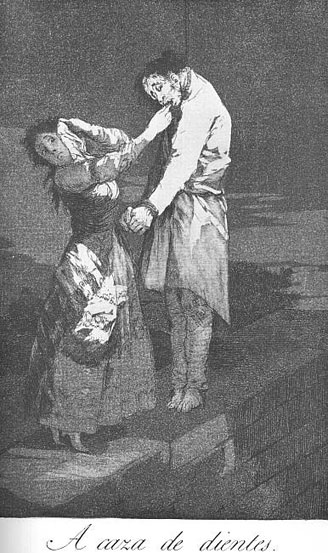

Out Hunting for Teeth

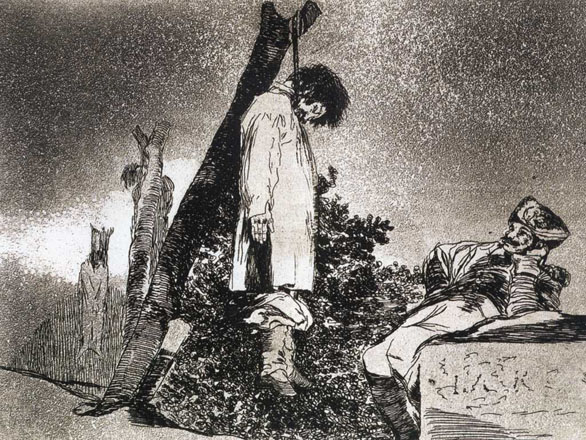

The young woman, recoiling in fear at the sight of the hanged man, is nevertheless reaching greedily into his mouth for his teeth, which are precious ingredients for magic potions.

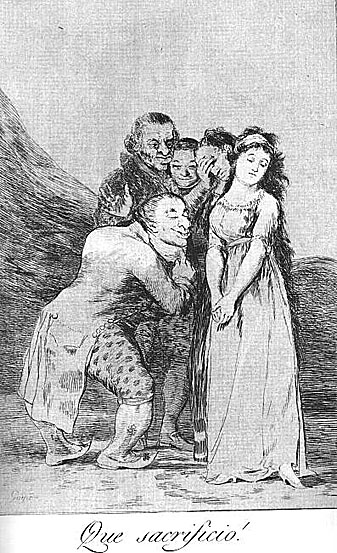

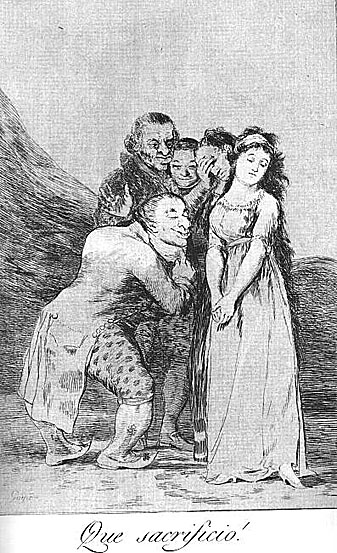

What a Sacrifice

For Heaven's Sake and it was her Mother

The question of whom, or what Goya has targeted in the Caprichos has been a topic of debate ever since they were published. Early commentators often read his etchings as direct allegorical satires of prominent people within the Spanish establishment. A frequent assumption was that various etchings depicted Queen Maria Luisa and her lover Manuel Godoy; a pictorial critique of the cuckolding, manipulative Queen and her power hungry favorite. Another commonly held belief asserted that the various beautiful dark haired majas depicted in the work were depictions of Goya's former companion, the Duchess of Alba.

However, the identification of particular plates with individuals contradicts Goya's claim made in an advertisement of 1799: "In none of the compositions which form part of this collection has the author proposed to ridicule the particular defects of any one individual…". Admittedly these are comments any sensible artist would make to protect themselves regardless of true intention. Indeed, a degree of misdirection and ambiguity would have been essential in Spain in contrast to, for example England, if one intended to target important people; the absence of legislation permitting freedom of expression fostered a climate where artists could be sued for defamation quite freely. Nonetheless, the majority of modern critics now accept that, while one or two plates do seem to lampoon individuals explicitly, the majority of the plates, as Goya states in 1799, criticize, "the innumerable foibles and follies to be found in any civilized society … the common prejudices and deceitful practices which custom, ignorance and self interest have made usual". Orthodox critical opinion now conjectures that apparent similarities between characters portrayed and real people reflect the artist's practice of casting known individuals as templates for certain "types" of humanity and human folly.

It is Nicely Stretched

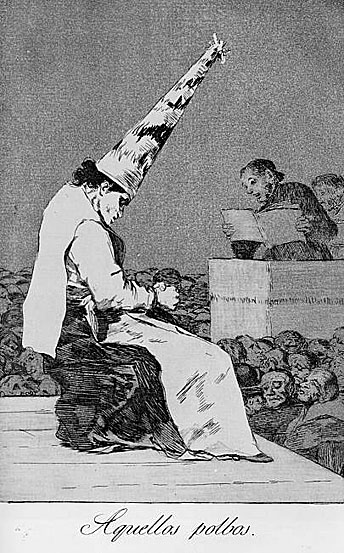

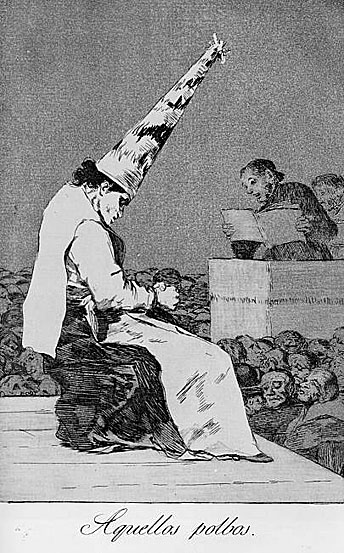

Those Specks of Dust

Nothing Could be Done About it

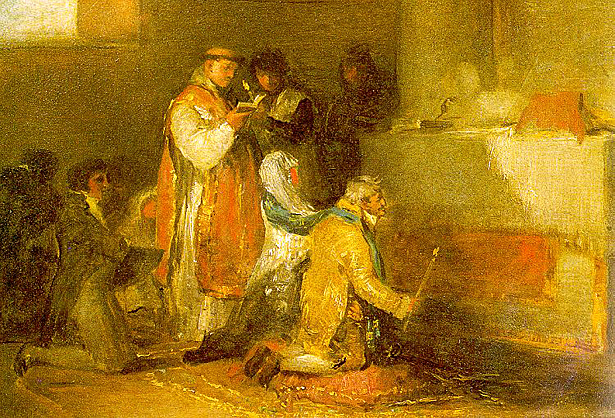

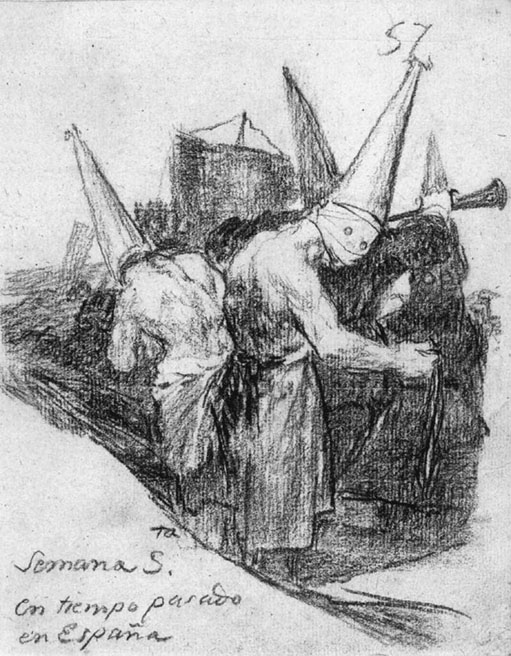

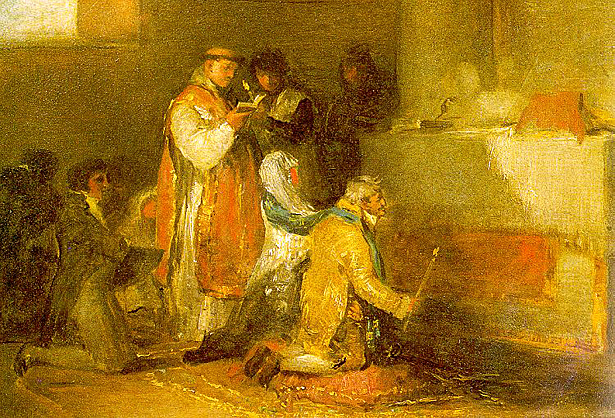

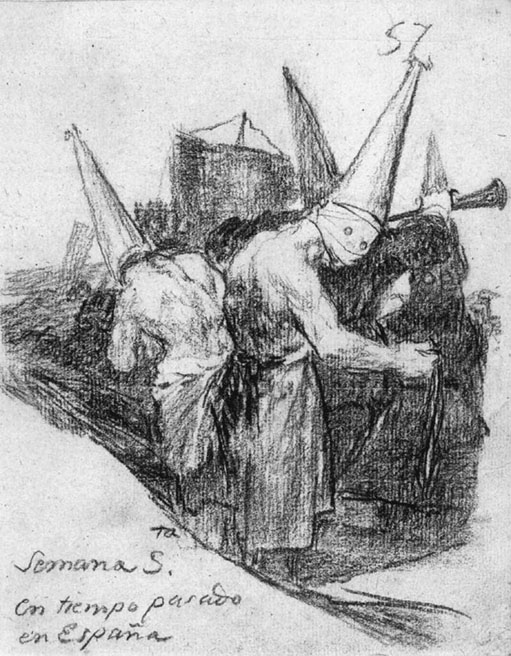

Those condemned by the Inquisition were publicly paraded wearing a distinctive conical hat signaling their disgrace.In 1807 a French traveller in Valencia watched an alleged witch, "her upper body bared to the waist", being lead through every quarter of the town.

Which of them is More Overcome

Because she was Susceptible

"Por que fue sensible" (Because she was susceptible). Goya's depiction of a young girl incarcerated is the only plate in Los Caprichos to have no etched lines and is formed solely through aquatinting. Consequently the depth and intensity of the darkness mirrors the emotions of the subject.

A Bad Night

Of What Ill Will he Die

"¿De qué mal morirá?" (What will he die from?). Here the artist targets doctors who he obviously considers dangerously ignorant. With this caption, Goya suggests that the treatment form the ignorant doctor may be just as dangerous as the illness from which the patient is suffering!

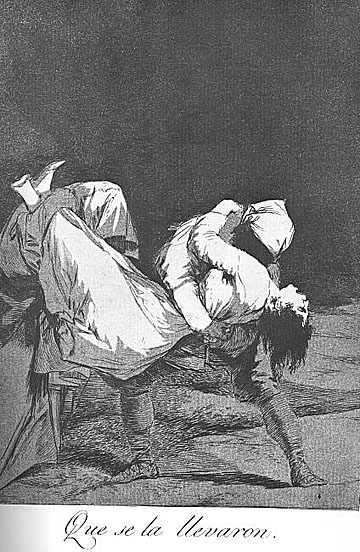

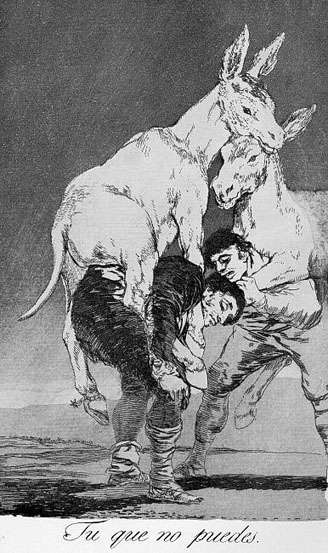

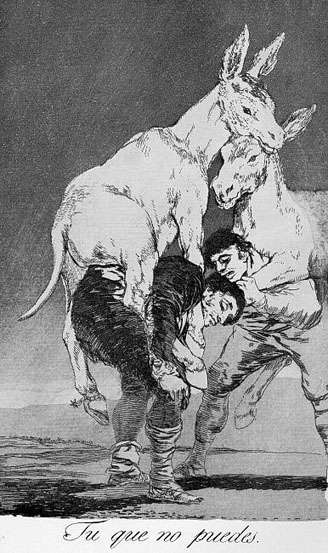

They who Cannot

"Tu que no puedes" (You who cannot). Goya unites the trope of the topsy-turvey world and the practice of symbolizing humans as donkeys to target the nobility metaphorically riding on the backs of the hard working poor.

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters

Sinister creatures of the night torment the artist - presumably Goya himself - who lies slumped over his table, unable to work. Yet the real clue to Goya's print lies in its subtitle: 'Imagination abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters; united with her, she is the mother of the arts.'

The etching of the sleeping artist, threatened by fantastical faces, was originally intended to open the Caprichos series. Goya later decided to replace it with a self-portrait, the picture of a self-assured man dressed in a top and wearing a critical expression.

They Spin Finely

Homage to the Master

Tale Bearers Blasts of Wind

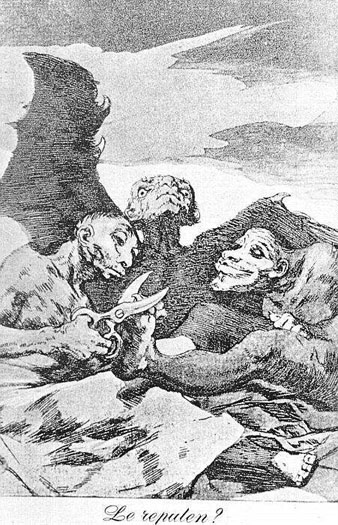

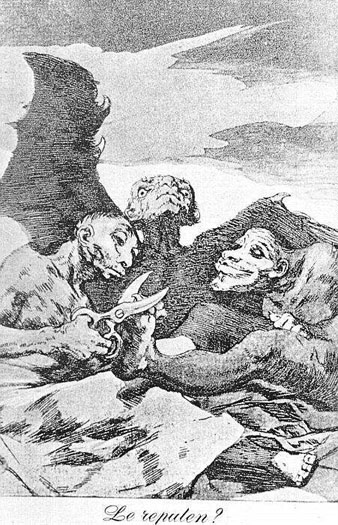

They spruce themselves up

Janis A. Tomlinson suggests that many of the witchcraft series were produced far earlier than the social satires found at the start of the volume. She argues that this might indicate that Goya had no direct satirical intention with many of his witchcraft images and that he merely uses them to play around with and challenge traditional ideas of form. She suggests that some of the last witchcraft images to be produced, for example, plate 51, "Se repulen" (They spruce themselves up) progress from the earlier ones and began to incorporate satirical, allegorical elements. By picturing three goblins preening and posturing, Goya is blurring the line between fantasy and reality. "These goblins are involved in vain activities previously thought endemic to man alone … These shared vices enable us, in looking at Los Caprichos, to suspend our disbelief and equate goblins, monks, prostitutes and nobles as participants in a world that tests the limits of reason: no clear boundaries distinguish reality from fantasy".

What a Tailor can do

Women are sinking to their knees in front of a monk's habit. But clad in the habit is not a monk, but simply a stunted tree.

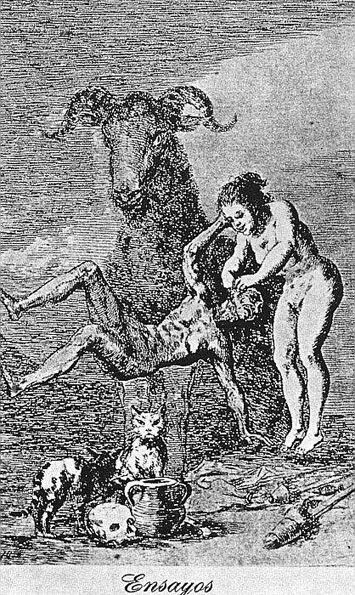

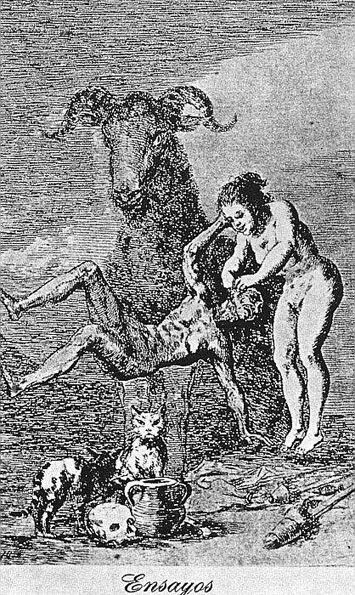

The Filiation

Experiments

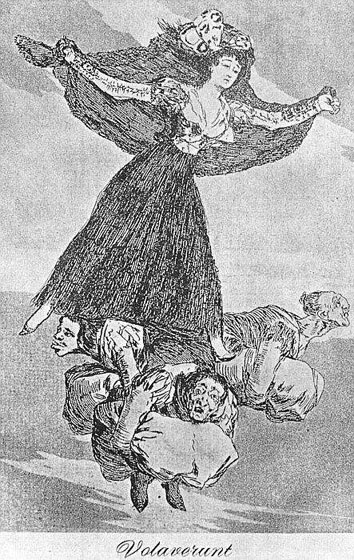

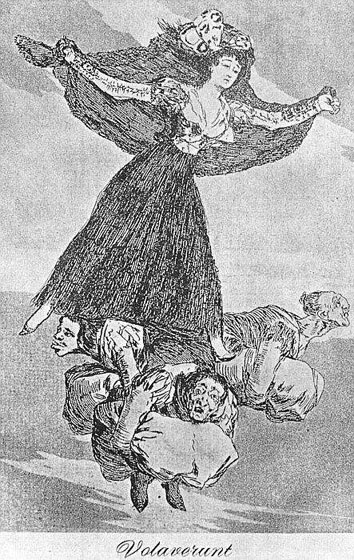

They are Flying

The Duchess of Alba appears also in Goya's Caprichos: standing proudly on the back of three witch-like figures, she flies through the air. The heads of the figures resemble those of famous bullfighters. The white, doll-like face of the Duchess appears haughtily reserved, and in her hair she wears butterfly wings as a symbol of unpredictable flightiness.

Look how Solemn they are

Bon Voyage

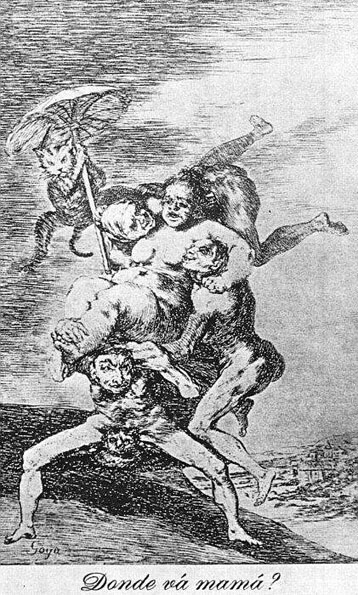

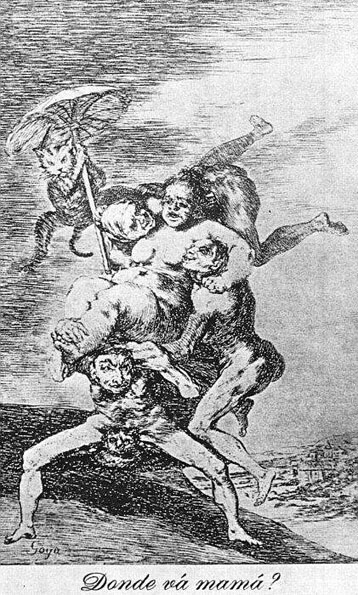

Where is Mama Going

Up They Go

Lovely Teacher

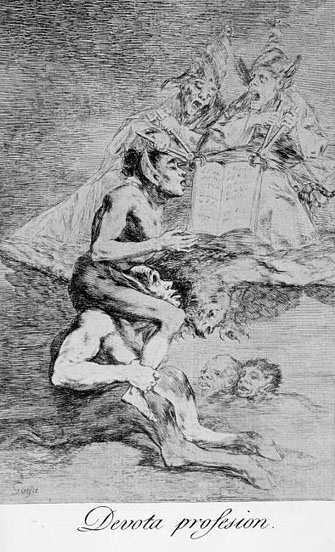

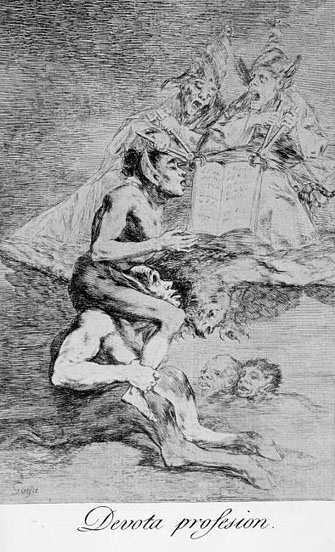

Devout Profession

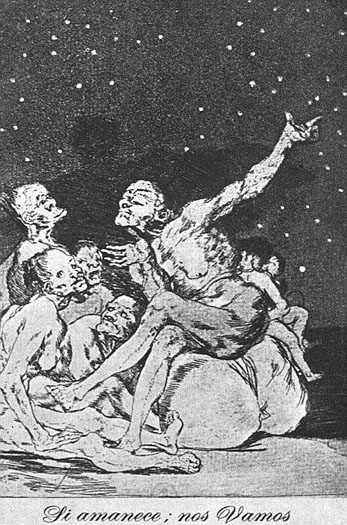

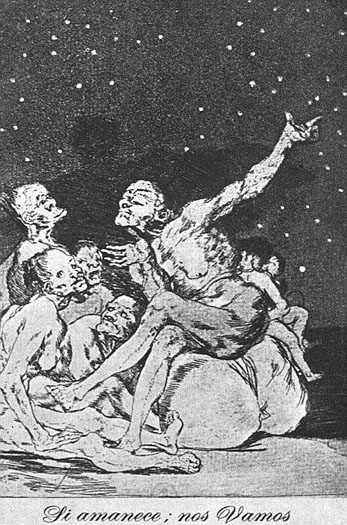

Dawn Comes We Go

You Cannot Escape

Can't Anyone Untie Us

It is Time

This of course was not everything that Goya put in Los Caprichos but I think that it provides a definite insight into his thinking and state of mind at this point in his life.

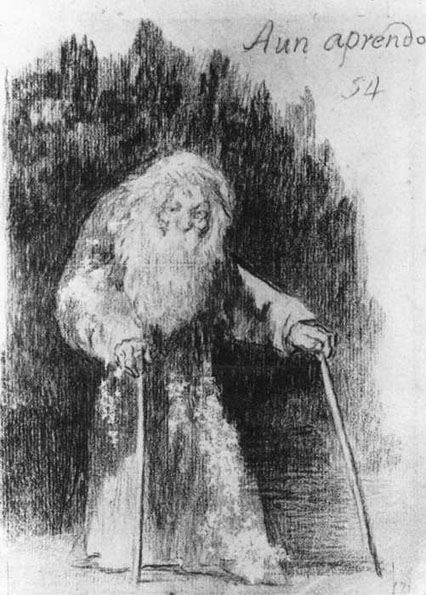

Senex Magister

Goya's art is remarkable in that his whole style and approach to painting changed in his mature years. This change coincided with a mystery illness the artist contracted in 1792. Nobody can be quite certain what the illness was although suggestions include syphilis, polio, menières's disease and lead poisoning; however, the end result was the complete loss of Goya's sense of hearing. It took Goya many years to fully return to painting and etching and during the recuperation period, divested of his commissioned workload, he experimented greatly in style. Upon returning to painting and etching at the end of the 1790s, Goya had thrown off the influence of the rococo; his art gained a significantly darker, original tone. Not only had his style changed but his choice of subject matter too. He became markedly more interested in the grim everyday reality of Spain and the Spanish people. His characters, often twisted, grizzled and contorted depictions of the poor, the ignorant or the insane arguably reflected the mounting social tensions between old, "black" Spain of tradition and superstition and the modernizing influence of an increasingly rationalizing Europe.

In 1786 Goya was appointed painter to Charles III, and in 1789 was made court painter to Charles IV. In 1799 he was appointed First Court Painter with a salary of 50,000 reales and 500 ducats for a coach. He worked on the cupola of the Hermitage of San Antonio de la Florida; he painted the King and the Queen, royal family pictures, portraits of the Prince of the Peace and many other nobles. His portraits are notable for their disinclination to flatter, and in the case of The Family of Charles IV, the lack of visual diplomacy is remarkable.

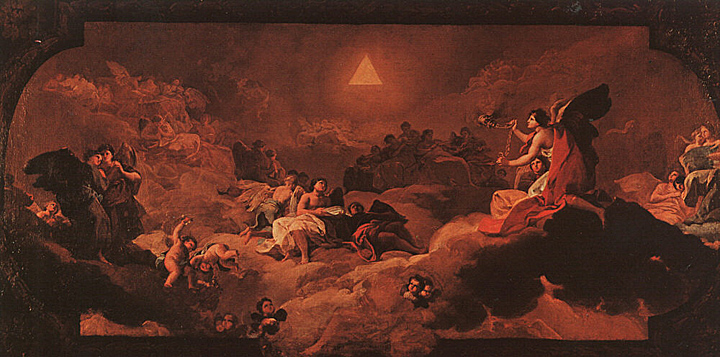

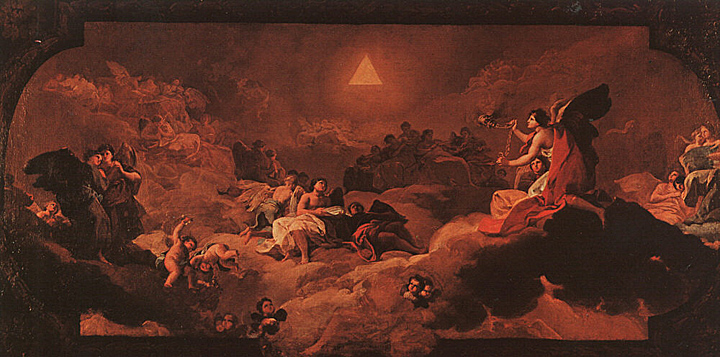

Hermitage of San Antonio de la Florida

The Miracle of Saint Anthony: 1798

Charles IV and Maria Luisa granted Goya a free hand in designing and executing the decorative scheme for the chapel of St Anthony. The artist gave the cupola a heaven entirely devoid of celestial beings. The figures we see instead are pious, happy and boisterous human beings. Not all of them are watching the miracle being performed by St Anthony, who is bringing a dead man back to life so that the latter can reveal who murdered him.

Manuel Godoy, Duke of Alcudia, 'Prince of the Peace'

This portrait was painted between July and October 1801 to commemorate the victory in Portugal, the War of the Oranges, so-called because Godoy, Chief Minister, is said to have sent a gift of oranges to the Queen in celebration. The Portuguese banners prominent in the foreground were awarded to Godoy in July and in October he was made Generalissimo of land and sea, which entitled him to wear a blue sash in place of the red sash of Captain General, which he wears here.

Goya has portrayed Godoy in an elaborate and unusual composition, in a reclining posture reminiscent of some of his paintings of women on couches, seemingly inappropriate for the hero of a military victory. Goya's portrait hints at disrespect for the pomposity of his sitter, though Godoy was an important patron, a collector on a grand scale, for whom Goya painted many works including the famous portrait of his wife, the Countess of Chinchon. Godoy was also owner of the two Majas and may even have commissioned them.

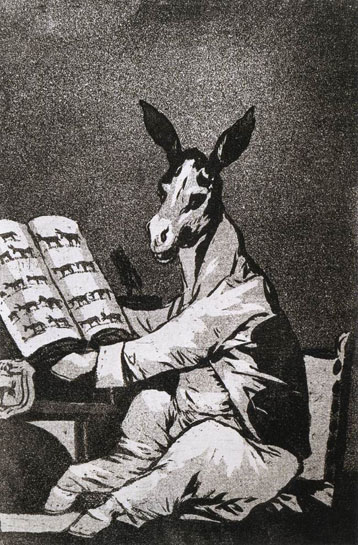

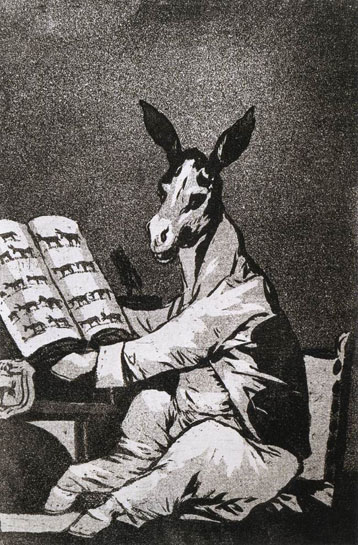

Goya's friendship with liberal ministers, such as Jovellanos and Saavedra, did not affect the relationship between the First Court Painter and the Chief Minister, whose rapid rise to power, attributed to his liaison with the Queen, made him notorious. Godoy must have been aware of the fact that he had been and still was the target of Goya's satirical wit in several plates of Los Caprichos, the ass looking up his genealogy in a book illustrated with row after row of asses, for instance, and in the etching entitled Birds of a Feather (Tal para qual). According to contemporary commentaries this is a reference to Godoy and Queen María Luisa, in particular to an occasion when she was mocked by a group of washerwomen for her unseemly behaviour. Yet despite all this, Godoy in his Memoirs written years later in France referred to Goya's Caprichos with pride as if he had been responsible for their publication.

Charles IV and his Family: ca 1800

Goya clearly had in mind for this royal group the composition of Velázquez's Meninas, which he had copied in an engraving many years before. Like Velázquez, he has placed himself at an easel in the background, to one side of the canvas. But his is a more formal royal portrait than Velázquez's: the figures are grouped almost crowded together in front of the wall and there is no attempt to create an illusion of space. The eyes of Goya are directed towards the spectator as if he were looking at the whole scene in a mirror. The somewhat awkward arrangement of the figures suggests, however, that he composed the group in his studio from sketches made from life. Goya is known to have made four journeys to Aranjuez in 1800 to paint ten portraits of the royal family. Since there are 12 figures in the group it is likely that the woman seen in profile and the woman whose head is turned away — the only two whose identity is uncertain were not present at the time.

Goya's magnificent royal assembly is dominated not by Charles IV but by the central figure of the Queen, María Luisa, whose ugly features are accentuated by her ornate costume and rich jewels. For some unknown reason this was the last occasion that Goya is known to have painted any member of this royal family, except for the future Ferdinand VII, who stands in the foreground on the left. The unusual figure composition on the wall behind the group has been identified as Lot and his Daughters, but no such painting has been identified.

Goya received orders from many friends within the Spanish nobility. Among those from whom he procured portrait commissions were Pedro de Álcantara Téllez-Girón, 9th Duke of Osuna and his wife María Josefa de la Soledad, 9th Duchess of Osuna, María del Pilar Teresa Cayetana de Silva y Álvarez de Toledo, 13th Duchess of Alba (universally known simply as the "Duchess of Alba"), and her husband José Álvarez de Toledo y Gonzaga, 13th Duke of Alba, and María Ana de Pontejos y Sandoval, Marchioness of Pontejos.

Pedro de Álcantara Téllez-Girón, 9th Duke of Osuna

María Josefa de la Soledad, 9th Duchess of Osuna

María del Pilar Teresa Cayetana de Silva y Álvarez de Toledo, 13th Duchess of Alba

Goya had a close and lasting friendship with the Duchess, who was the last of an old noble line, and famous for her beauty, wit, and intelligence. When Goya was stricken with the mysterious illness that paralyzed him for a time, she arranged devotedly for his care. The full figure portrait can be interpreted as fervent thanks for her friendship. The painter has put his affection into the picture in a dedication written in the sand, to which the Duchess pointing: "A la Duquesa de Alba. Fr. de Goya 1795." The band of friendship on her wrist also bears his initials. Goya wanted to show her to posterity with a mild but watchful gaze. Her candid expression is emphasized by the raised brows and the framing curly hair. The palette is reduced to a few colours, the landscape is bare and the simplicity of the handling may stand for the sincerity of their friendship. Goya kept the painting, intending never to part with it.

Goya painted the Duchess two years later, dressed in black lace, and the motto to which she is pointing betrays their relationship: "Solo Goya!"

The Duchess of Alba: 1797

The thirteenth Duchess of Alba was born in 1762, widowed in 1796 and died in 1802 in mysterious circumstances, which gave rise to the rumor that she was poisoned. She was a prominent figure in Madrid society. Goya's relations with the Duchess were such that they have led to the suggestion that she posed for La Maja Desnuda. He stayed with her at her Andalusian estate in Sanlúcar after her husband's death and made several drawings of scenes in the domestic life of the Duchess and her household. She is also recognizable in several plates of Los Caprichos and in one unpublished etching, which seems to record an estrangement from the artist. The present portrait was almost certainly painted during Goya's stay at Sanlúcar and remained in his possession.

The name Alba on the ring on the Duchess's third finger and Goya on that on the downward-pointing index finger are in themselves evidence of Goya's intimacy with his sitter. The inscription on the ground at the Duchess's feet, to which her finger points (only uncovered in modern times), reads Solo Goya, the word solo ('only') strengthening the assumption that they were lovers. The stiff figure with its expressionless face is, however, more like the puppet-like figures of the tapestry cartoons than a portrait of a familiar sitter.

Jose Alvarez Duke Consort of Alba

In 1756, Álvarez de Toledo y Gonzaga was born on 16 July in Madrid.

He was chamberlain to King Charles IV of Spain. He, originally Marquess of Villafranca, married his kinswoman Doña María del Pilar Teresa Cayetana de Silva y Álvarez de Toledo, 13th Duchess of Alba, who was the legendary "Duchess of Alba" in Goya's paintings, thus becoming the Duke consort of Alba in her right. A year after his marriage, he inherited the dukedom of Medina-Sidonia and joined two of the most important Houses of the Spanish nobility.

The failed attempt of his friend Alejandro Malaspina to oust Queen Maria Louisa's favorite Manuel de Godoy in favor of the Duke of Alba put an early end to the political career of the progressive aristocrat.

In 1796, Álvarez de Toledo y Gonzaga died on 9 June in Seville.

In a famous portrait painting by Goya, the duke is clad in elegant riding clothes. With an air of melancholy he looks up from the music book he is holding in his hands, including the "Four songs/with piano accompaniment/by Mr. Haydn". The duke commissioned several works from Joseph Haydn and was a gifted musician himself. In his painting, Goya subtly combines the symbols of his model's passion for music and equestrian skills (viola or violin, riding boots and riding hat) with the neoclassical interior of the ducal residence.

María Ana de Pontejos y Sandoval, Marchioness of Pontejos

Doña María Ana de Pontejos y Sandoval, the Marquesa de Pontejos, is holding a pink carnation, an emblem of love and brides. In 1786, at age twenty-four, she married the brother of the Count of Floridablanca, Charles III's progressive Prime Minister. At that time, her husband served as Spain's ambassador to Portugal.

As French forces invaded Spain during the Peninsular War (1808-1814), the new Spanish court received him as had its predecessors.

When Josefa died in 1812, Goya was painting The Charge of the Mamelukes and The Third of May 1808, and preparing the series of prints known as The Disasters of War (Los desastres de la guerra).

The Charge of the Mamelukes: 1814

After the expulsion of the Napoleonic armies in 1814 Goya applied for, and was granted, official financial aid in order 'to perpetuate with the brush the most notable and heroic actions or scenes of our glorious insurrection against the tyrant of Europe'. The two scenes that he recorded are not victorious battles but acts of anonymous heroism in the face of defeat. Here the people of Madrid armed with knives and rough weapons are seen attacking a group of mounted Egyptian soldiers (Mamelukes) and a cuirassier of the Imperial army. The composition, without a focal point or emphasis on any single action, creates a vivid impression of actuality, as if Goya had not only witnessed the scene (as he is alleged to have done) but had recorded it on the spot.

The Third of May 1808: The Execution of the Defenders of Madrid

Painted at the same time as The Second of May, Goya here represents another of the 'most notable and heroic actions...of our glorious insurrection against the tyrant of Europe' by a dramatic execution scene. The insurrection of the people of Madrid against the Napoleonic army was savagely punished by arrests and executions continuing throughout the night of 2 May and the following morning. There is a legend that Goya witnessed the executions on the hill of Príncipe Pío, on the outskirts of Madrid, from the window of his house and that, enraged by what he had seen, he went to visit the spot immediately afterwards and made sketches of the corpses by the light of a lantern.

Whether Goya saw for himself or knew them by hearsay only, the military executions of civilians is a theme that evidently impressed him deeply. He represented it in several etchings of Los Desastres de la Guerra and in some small paintings as well as in this monumental picture. Here the drama is enacted against a barren hill beneath a night sky. The light of an enormous lantern on the ground between the victims and their executioners picks out the white shirt of the terrified kneeling figure with outstretched arms. The postures, gestures and expressions of the madrilenos and the closed impersonal line of the backs of the soldiers facing them with levelled muskets, emphasize the horror of the scene. The dramatic qualities of this composition, with its pity for the execution of the anonymous victims and its celebration of their heroism, inspired Manet's several versions of the Execution of Maximilian.

King Ferdinand VII came back to Spain but relations with Goya were not cordial. In 1814 Goya was living with his housekeeper Doña Leocadia and her illegitimate daughter, Rosario Weiss; the young woman studied painting with Goya, who may have been her father. He continued to work incessantly on portraits, pictures of Santa Justa and Santa Rufina, lithographs, pictures of tauromachy, and more. With the idea of isolating himself, he bought a house near Manzanares, which was known as the Quinta del Sordo (roughly, "House of the Deaf Man", titled after its previous owner and not Goya himself). There he made the Black Paintings.

King Ferdinand VII with Royal Mantle

With the French finally expelled, in 1814 Ferdinand VII returned from exile. The 30-year-old monarch proceeded to hound Spain's liberals, with whom Goya was closely affiliated. Anxious to keep his post and salary as Court Painter, Goya executed six portraits of the King, none of them commissioned.

FERDINAND VII, King of Spain

1784-1833, king of Spain (1808-33), son of Charles IV and María Luisa. Excluded from a role in the government, he became the center of intrigues against the chief minister Godoy and attempted to win the support of Napoleon I. In 1807 he was arrested by his father, who accused him of plotting his overthrow and the murder of his mother and Godoy. He was soon forgiven, but the prestige of the family was shaken, and this facilitated Napoleon's invasion of Spain (see Peninsular War). A palace revolution at Aranjuez caused the dismissal of Godoy and the abdication of Charles in favor of Ferdinand, who was enthusiastically acclaimed by the people. Ferdinand was soon persuaded to cross the French border and meet Napoleon at Bayonne. There he was forced to renounce his throne in favor of Charles IV, who in turn resigned his rights to Napoleon. The emperor gave the Spanish throne to Joseph Bonaparte. During the Peninsular War (1808-14) Ferdinand was imprisoned in France. In his name the nationalist and liberal elements of Spain resisted the French invaders, and a liberal constitution was proclaimed (1812) by the Cortes at Cádiz. Throughout the Spanish Empire his name was the rallying cry of revolutionary elements. When Ferdinand was restored (1814) to his throne, however, he promptly abolished the liberal constitution and revealed himself a thorough reactionary. After several unsuccessful uprisings, the Spanish liberals (who had organized in secret societies such as the Carbonari) staged a successful revolution in 1820 and forced the king to reinstate the constitution of 1812. The Holy Alliance became alarmed, and the Congress of Troppau was summoned to deal with the Spanish situation. The powers reached no decision, but in 1822 at Verona France was delegated by the Holy Alliance to undertake military intervention in Spain and to restore Ferdinand to absolute power. Ferdinand, backed by French arms, revoked the constitution in 1823, and ruthless repression followed. Ferdinand's death caused no less trouble than his reign. His fourth wife, Maria Christina (1806-78), had persuaded him to set aside the Salic Law so that their only child, Isabella, might succeed to the throne, thus excluding Ferdinand's brother, Don Carlos (1788-1855), from the succession. When Ferdinand died, the liberals supported Isabella II, while the reactionaries rallied around Don Carlos. The Carlist Wars ensued. During Ferdinand's reign, the Spanish colonies on the mainland of North and South America were lost through the very rebellions that had begun as risings in his favor and against Napoleon.

Unsettled and discontented, he left Spain in May 1824 for Bordeaux and Paris. He settled in Bordeaux. He returned to Spain in 1826 after another period of ill health. Despite a warm welcome, he returned to Bordeaux where he died in 1828 at the age of 82.

Goya painted the Spanish royal family, including Charles IV of Spain and Ferdinand VII. His themes range from merry festivals for tapestry, draft cartoons, to scenes of war and corpses. This evolution reflects the darkening of his temper. Modern physicians suspect that the lead in his pigments poisoned him and caused his deafness since 1792. Near the end of his life, he became reclusive and produced frightening and obscure paintings of insanity, madness, and fantasy. The styles of these Black Paintings prefigure the expressionist movement. He often painted himself into the foreground.

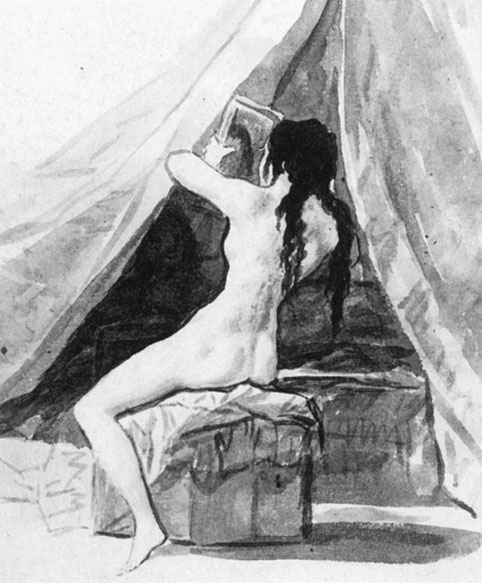

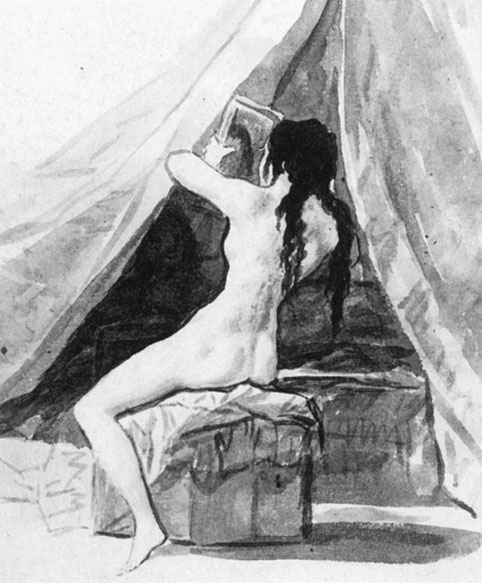

Two of Goya's best known paintings are The Nude Maja (La maja desnuda) and The Clothed Maja (La maja vestida). They depict the same woman in the same pose, naked and clothed, respectively. He painted La maja vestida after outrage in Spanish society over the previous Desnuda. Without a pretense to allegorical or mythological meaning, the painting was "the first totally profane life-size female nude in Western art". He refused to paint clothes on her, and instead created a new painting.

Nude Maja (La Maja Desnuda): ca 1799-1800

Goya's Majas (fashionable young women) are two of his most famous and most discussed masterpieces. Their date, for whom they were painted and the identity of the model are problems that are still not satisfactorily solved. The first mention of The Nude Maja is in the diary of the medallist Pedro Gonzalez de Sepulveda describing a visit in November 1800 to the house of the Minister, Manuel Godoy, Goya's patron and the target of his satire: 'In an apartment or inner cabinet are pictures of various Venuses... [among them] a naked one by Goya, without design or delicacy of colouring' and Velázquez's 'famous Venus'. There is no mention of The Clothed Maja and presumably it was not there, probably not yet painted.

Godoy's position at court and his known taste for paintings of female nudes (there were many others in his collection) makes it likely that both Majas were painted for him. An alternative suggestion is that they were in the Duchess of Alba's collection and acquired by Godoy after her death, together with Velázquez's The Toilet of Venus and other pictures. Goya's relations with the Duchess of Alba have made her the most popular candidate as a model for the Majas, at least as a source of inspiration, supported by the many drawings of herself and members of her household he made during his visit to the Duchess's country estate. The lack of resemblance to the heads of Goya's earlier portraits of her is usually explained by the need to conceal her identity. Whoever the model may have been and for whomever the pictures were made, Goya's nude Maja is unique and unprecedented in his oeuvre and in Spain, even in Europe, in his time. Velázquez's Venus, which Goya must have seen in the Duchess of Alba's collection, is its only comparable predecessor in the life-like portrayal of the female nude. But where the Velázquez is also a mythological painting, Goya's The Nude Maja makes no pretence of being anything but the rendering of a naked woman lying on a couch.

Clothed Maja (La Maja Vestida): ca 1800-03

Though it was no doubt painted earlier, the first record of The Clothed Maja and the first mention of the paintings together is in an inventory of Godoy's collection dated 1 January 1808, where they are called 'gipsies'. In an article on Los Caprichos published in Cadiz in 1811, it is as Goya's Venuses that they are mentioned amongst his most admired works (they are also called Venuses in Goya's biography by his son). The next mention of the Majas is towards the end of 1814, when Goya was denounced to the Inquisition for being the author of two obscene paintings in the sequestrated collection of the Chief Minister Godoy, 'one representing a naked woman on a bed...and the other a woman dressed as a maja on a bed'. On 16 May 1815, the artist was summoned to appear before a Tribunal 'to identify them and to declare if they are his works, for what reason he painted them, by whom they were commissioned and what were his intentions'. Unfortunately Goya's declaration has not yet come to light.

As a pair of paintings of a single figure in an identical pose, the Majas are a highly original invention. The theory that the clothed woman was intended as a cover for the naked one is very credible. It is not surprising that the Majas attracted the attention of the Inquisition in Madrid in 1814. As late as 1865 Manet's Olympia (which bears such a close resemblance to The Naked Maja that it is difficult to believe that the artist had not seen Goya's painting) created a furious scandal when it was exhibited in the Paris Salon.

The identity of the Majas is uncertain. The most popularly cited subjects are the Duchess of Alba, with whom Goya is thought to have had an affair, and the mistress of Manuel de Godoy, who subsequently owned the paintings. Neither theory has been verified, and it remains as likely that the paintings represent an idealized composite. In 1808 all Godoy's property was seized by Ferdinand VI after his fall from power and exile, and in 1813 the Inquisition confiscated both works as 'obscene', returning them in 1836.

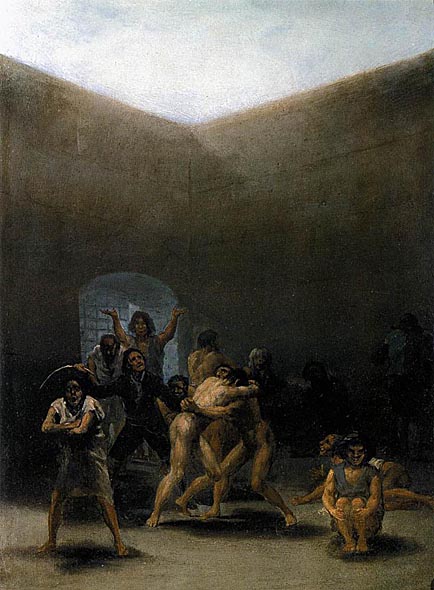

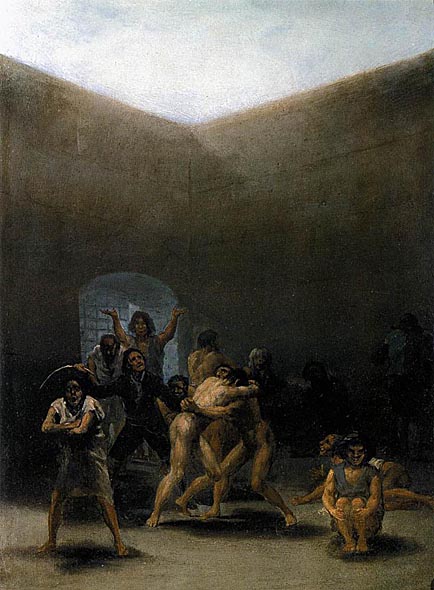

In a period of convalescence during 1793-1794, Goya completed a set of eleven small pictures painted on tin; the pictures known as Fantasy and Invention mark a significant change in his art. These paintings no longer represent the world of popular carnival, but rather a dark, dramatic realm of fantasy and nightmare. Courtyard with Lunatics is a horrifying and imaginary vision of loneliness, fear and social alienation, a departure from the rather more superficial treatment of mental illness in the works of earlier artists such as Hogarth. In this painting, the ground, sealed by masonry blocks and Iron Gate, is occupied by patients and a single warden. The patients are variously staring, sitting, posturing, wrestling, grimacing or disciplining themselves. The top of the picture vanishes with sunlight, emphasizing the nightmarish scene below.

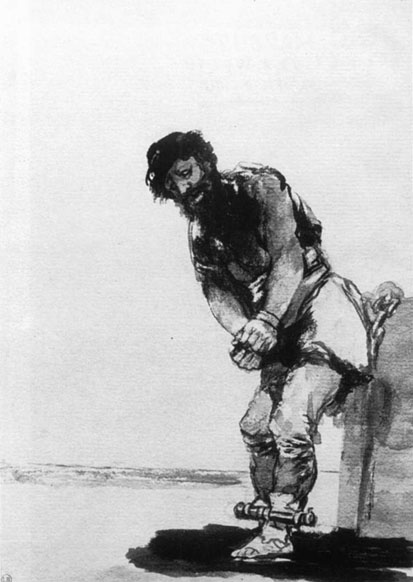

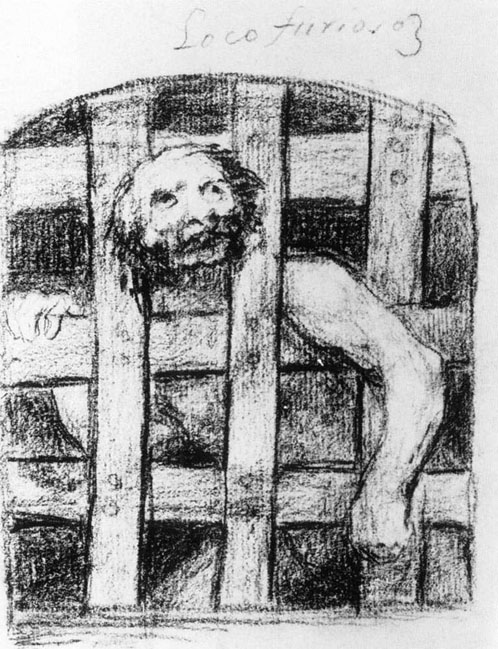

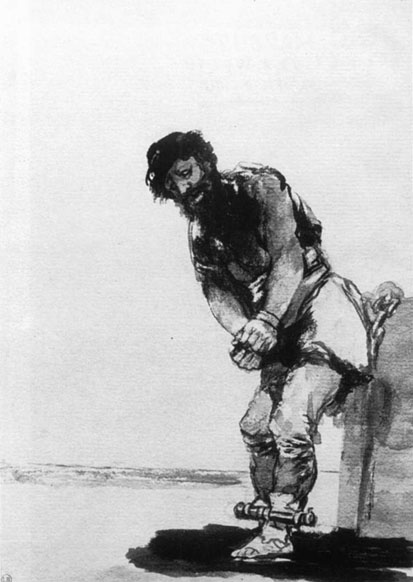

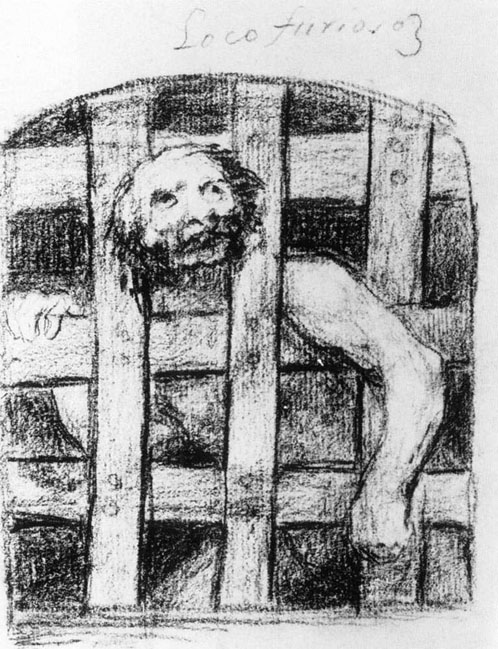

A Lunatic Behind Bars: 1824-28

Many of Goya's etchings and drawings testify to his concern for the plight of lunatics and prisoners throughout his life.

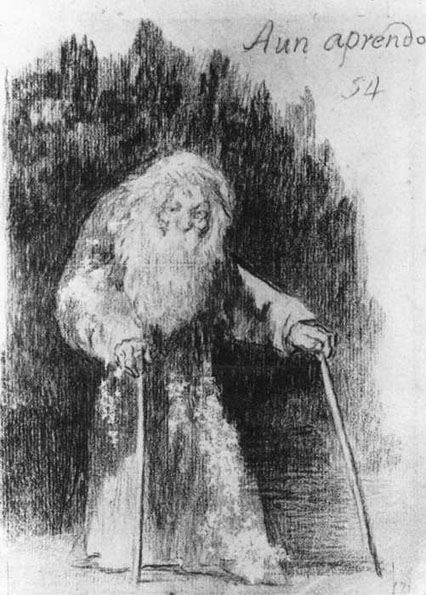

'I am Still Learning' ('Aún aprendo'): 1824-28

Until the end of his life Goya, in spite of old age and infirmity, continued to record the world around him in paintings and drawings and in the new technique of lithography.

This picture can be read as an indictment of the widespread punitive treatment of the insane, who were confined with criminals, put in iron manacles, and subjected to physical punishment. And this intention is to be taken into consideration since one of the essential goals of the enlightenment was to reform the prisons and asylums, a subject common in the writings of Voltaire and others. The condemnation of brutality towards prisoners (whether they were criminals or insane) was the subject of many of Goya's later paintings.

The Yard of a Madhouse:1794

While he was recovering from the serious illness that left him totally deaf, Goya occupied himself with a series of 'cabinet' paintings which he sent to the Academy and which won approval as scenes of 'national pastimes'. A few days later, he followed these with a twelfth painting of a very different character, which he described in detail in a letter to the Director. The rediscovery of this picture in 1967 provided a touchstone for the identification of the rest of the set of cabinet pictures that Goya had sent to the Academy which are now considered to include subjects such as a Shipwreck and a Fire hardly to be described as national pastimes as well as Strolling Players, and possibly a group of Bullfight scenes.

The Madhouse and other small paintings now in the Academy, once thought to have been among the scenes of so-called national pastimes are now generally attributed to a considerably later date, for stylistic reasons. The Yard of a Madhouse is one of many scenes Goya recorded that he had actually witnessed, among them some of the war scenes in the Desastres (with the titles 'I saw this' and 'this too'). Many of his etchings and drawings testify to his concern for the plight of lunatics and prisoners throughout his life. See, for instance, the drawing of a madman behind bars made in Bordeaux.

A Prison Scene: 1810-14

This prison scene is related in style and character to a number of small paintings of war scenes and other subjects inspired by the Napoleonic invasion. Prisoners - not only prisoners of war - are among the victims of injustice and cruelty that figure in many of Goya's drawings and engravings. A garroted man is the subject of one of his earliest etchings and various other forms of punishment and torture are represented in later graphic works. Three etchings of about 1815 show chained and shackled prisoners very similar to those in the painting. This prison scene, executed with a minimum of colour, is remarkable for the atmosphere of gloom and the effect of anonymous suffering created by the lightly painted, indistinct figures in an enormous cavern-like setting.

As he completed this painting, Goya was himself undergoing a physical and mental breakdown. It was a few weeks after the French declaration of war on Spain, and Goya's illness was developing. A contemporary reported, "the noises in his head and deafness aren't improving, yet his vision is much better and he is back in control of his balance." His symptoms may indicate a prolonged viral encephalitis or possibly a series of miniature strokes resulting from high blood pressure and affecting hearing and balance centers in the brain. Other postmortem diagnostic assessment points toward paranoid dementia due to unknown brain trauma (perhaps due to the unknown illness which he reported). If this is the case, from here on - we see an insidious assault of his faculties, manifesting as paranoid features in his paintings, culminating in his black paintings and especially Saturn Devouring His Sons.

Saturn Devouring One of his Children: 1819-23

This painting (Saturno devorando a un hijo) was originally in the ground floor room of the Quinta del Sordo.

Saturn Devouring One of his Children is perhaps the cruellest of the Black Paintings.The nightmare quality is combined with myth to make an epochal statement: this is the madness of truth. Whether this is a reflection of Goya's own mental state, or an allegory on the situation in a country that was consuming its own children in bloody wars and revolutions, or a statement on the human condition generally, may remain open. It could also be a reflection of the situation of the enlightened man who has lost his God and is able to experience only mercilessness on cosmic scale.

Reading: 1820-21

Asmodea: 1820-23

Asmodi was a demon who lifted off the roofs of houses and revealed to his companion the licentious ways of their inhabitants. Probably an allusion to the artist's 'illicit relationship' with Leocadia Weiss.

_1820_23.jpg)

Manola (La Leocadia): 1820 23

The woman dressed in mourning may represent Leocadia Weiss, who became Goya's partner after the death of his wife, Josefa. She is leaning against a mound of earth with a grave rail on top. The artist offers no explanation for the scene. It is possible that Goya himself is supposed to be lying in the grave, and that his Black Paintings are meant to be seen as messages from the hereafter.

A Pilgrimage to San Isidro: 1820-23

The Pilgrimage to San Isidro filled one long wall of the Quinta, opposite a painting called The Great He-Goat or Witches' Sabbath in the downstairs room of the house. Goya may have been prompted to paint this subject by the fact that the Quinta was built in the neighbourhood of the Hermitage of San Isidro and by the recollection of having painted the Hermitage and the Meadow of San Isidro in happier, earlier days. Without knowledge of the title, however, it would be hard to identify the procession of figures moving forward, their features becoming clearer and more awful as they get near, as a procession of pilgrims. Goya's viewpoint in this painting must have been close to that in the Meadow scene, but there is no view of the city in the background.

Two Monks: 1821-23

Two Women Eating: 1821-23

In 1799 Goya published a series of 80 prints titled Caprichos depicting what he called: (see above)

" ...the innumerable foibles and follies to be found in any civilized society, and from the common prejudices and deceitful practices which custom, ignorance, or self-interest have made usual. "

As far back as his grandfather: 1797-98

Goya caricatures the pride of the hidalgos. Some 500.000 of Spain's population of around 10 million considered themselves to belong to this lesser branch of the nobility. Since work was beneath their station, most of them were impoverished, their only possessions being a long line of ancestors.

The Colossus, 1810. In The Third of May, 1808: The Execution of the Defenders of Madrid, Goya attempted to "perpetuate by the means of his brush the most notable and heroic actions of our glorious insurrection against the Tyrant of Europe" The painting does not show an incident that Goya witnessed; rather it was meant as more abstract commentary.

The Colossus: 1808-12The giant is shown standing, his fists clenched for battle. The landscape is full of streams of people fleeing with their cattle.The painting makes it clear that mankind is dominated by fate, a force between heaven and earth. The demonic element, that has power over the earth, is depicted like a dream. Goya is basically using a Baroque device, allegory. He just makes the painting difficult to interpret, for we do not know whether the figure is intended to be a personification of revolution itself, of mankind exploding in rage, or its opposite, danger taking on visionary form.

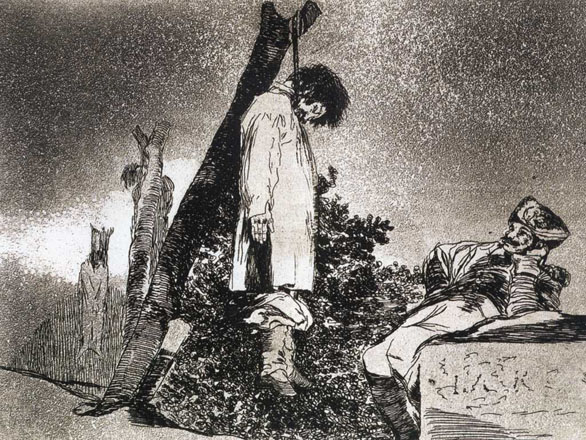

In the 1810s, Goya created a set of aquatint prints titled The Disasters of War (Los desastres de la guerra) which depict scenes from the Peninsular War. The scenes are singularly disturbing, sometimes macabre in their depiction of battlefield horror, and represent an outraged conscience in the face of death and destruction. The prints were not published until 1863, 35 years after Goya's death.

The Disasters of War (Los desastres de la guerra)

Mournful Foreboding of What is to Come: ca 1810

The same: 1810-15

What courage!

Goya reacted to the struggle against the French with The Disasters of War, his second great cycle of etchings after Los Caprichos. It extends to over 80 plates, but includes only few acts of heroism, such as that of the young woman who fires the cannon after all the men are dead.

What more can one do?

French soldiers castrate or kill a defenceless man. This is another scene that the artist, living in Madrid, probably did not see at first hand. Brutality and death fired his imagination.

Here neither

Contemplating the man who has just lost his life - is a uniformed soldier, leaning back in a relaxed fashion. Like him, Goya too questions the sense of killing.

This is worse: 1812-15

A tree trunk pierces the body and emerges at the shoulder - not a realistic scene of war, but Goya's vision of a martyred man.

The Worst is to Beg: 1812-15

This plate is one of the many illustrations of the effects of famine in the series. In the 'ano del hambre', the year of the terrible famine in Madrid in 1811-12 thousands died of hunger.

Cartloads to the cemetery: 1812-15

War is ravaging the country, the fields are left unfilled and in the city the people are starving, the poor first.

Nothing. The event will tell: ca 1812-20

This etching plays on the hope that, after death, we shall finally learn the truth. Goya shows a corpse raising itself back out of the tomb. It points to a piece of paper, on which is written "Nada" - "Nothing".

May the rope break: 1815-20

The Pope balances above the heads of the crowd. The hope that the rope might break was not fulfilled.

_1810_14.jpg)

Truth Has Died (Murio la verdad)

In the concluding plates of the Disasters of War are shown the burial of a beautiful young woman, followed by her exhumation or resurrection . Captioned Murio la verdad (Truth has Died), the first shows her body radiant with light as she lies in her grave and a looming priest administers the last rites. In the companion print, Si reucitaria? (Will She Rise Again?), she is exposed, her radiance and beauty faded, her face aged. Still she emits a glow that seems all the greater for the depth of background shadow - and sufficient to throw the crowd of peering ghouls into a frenzy. Here, the parallel hatching of the first etched plate is replaced by radiant lines, inked more intensely as they spread away from the body.

_1810_14.jpg)

Will She Rise Again? (Si reucitaria?)

This is the second day that I have been working on this page and my attitudes about Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes have wavered from a raving lunatic to the tragedy of one suffering from a severe neurosis. Now I see a man with a heart and a soul who has become the victim of the inhumanity that political leaders can inflict upon those whom they are supposed to protect and serve. After viewing these last pictures from Los desastres de la guerra, I am left with a sense of awe over Goya's insight into the human psyche. Yet, I also see a man tormented by the demons that arise from a depression where joy for whatevever reason can no longer be found. I am no expert on art and much less on a genius of one like Goya. These are only personal reflections of my own making and a pain I can too readily feel for a man who suffered so much as well as celebrating much as well. I have a few more paintings to leave you with that I was not able to fit in some place else.

Senex Magister

Allegory of the City of Madrid: 1810

At the end of 1809, during the French occupation of Madrid, Goya was chosen as 'el pintor madrileno por excelencia' to paint a portrait of Joseph Bonaparte for the City Council. In the absence of the French King, Goya composed this picture, described at the time as 'certainly worthy of the purpose for which it was intended', introducing the portrait of Joseph (after an engraving) in the medallion, to which the figure personifying Madrid points. With the changing fortunes of the war this portrait was replaced (by other hands) by the word 'Constitución', by another portrait of Joseph, again by 'Constitución' and at the end of the war by a portrait of Ferdinand VII. Eventually in 1843 it received the present inscription 'DOS DE MAYO' ('The second of May') in reference to the popular rising against the French in Madrid in 1808. The surprisingly conventional allegorical composition is perhaps dictated by the purpose for which it was originally painted. It contrasts strikingly with the realism and fervour of the scenes from the rising which Goya painted four years later.

Portrait of Antonia Zarate: ca 1805

The sitter was a leading actress, mother of the playwright Gil y Zárate and one of several members of the theatrical world portrayed by Goya. She was born in 1775 and was 30 years old at the time when this portrait was probably painted. She died in 1811. Another bust portrait has been dated earlier by some critics and later by others. But the pose and details of her face and coiffure are so similar only the dress and fancy headdress are different that the two portraits cannot be very different in date.

The liveliness of the close-up view of the bust portrait suggests that this may be Goya's first likeness of his beautiful sitter, later transformed into a grand composition. The problem of dating two versions of the same subject is not uncommon in Goya's oeuvre. The yellow settee appears in other portraits by Goya (for example the portrait of Pérez Estala in the Kunsthalle, Hamburg) and was probably a studio property. Nowhere, however, does it provide a more effective setting than here, as a background to the lovely dark-haired actress.

Antonia Zarate: 1811

Bartolomé Sureda y Miserol: 1804-06

Bartolomé Sureda was the director of the Spanish royal textile, crystal, and ceramic factories.He taught Goya the technique of aquatint. In 1804 Sureda became director of the porcelain works at the Buen Retiro.

Dona Teresa Sureda: 1805

This is the companion-piece of the portrait of Bartolomé Sureda y Miserol, also in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, representing the sitter's husband.

Birth of the Virgin: 1771-73

Charterhouse of the Aula Dei at Saragossa

Blind Man Playing the Guitar: 1778

Cardinal Luis Maria de Borbon y Vallabriga: 1798-1800

Don Luis María de Borbón y Vallabriga, Farnesio y Rozas, son of a morganatic marriage of Luis de Borbón y Farnesio, 13th Count of Chinchón, and wife María Teresa de Vallabriga y Rozas, Español y Drummond, was the 14th Conde de Chinchón (1785 -1803), Grandee of Spain First Class (4 August 1799), with a Coat of Arms of de Bourbon and 1st Marqués de San Martín de la Vega.

Till 1788, when the King Charles III of Spain died, this Bourbon offspring was compelled not to use the family name and since 1785 when his father, the King brother, died, he had to move to the city of Toledo to be educated under the protection of the Archbishop of Toledo Francisco Antonio de Lorenzana y Butrón (León, 22 September 1722 - Rome, 17 April 1804, aged 82), notorious cardinal, historian and "illustrated" Spaniard.

He was Cavaliere dell'insigne Reale ordini di San-Gennaro in 1793, Caballero del orden real de Carlos III in 1793, Archbishop of Seville, (26 May 1799 - 19 May 1814), Archbishop of Toledo, (22 December 1799 - 18 March 1823) and Primate of Spain in 1800 and Roman Cardinal of Santa Maria della Scala (Roma) on October 20, 1800.

He played an important role in Spanish Liberal Politics between 1820 and 1823, abolishing the Inquisition, albeit being restored again after the Invasion of Spain by European troops to restore absolutist policies (England, France, Austria, Russia).

He was made a Knight of the Golden Fleece on the 9th July 1820. He died aged around 46, a few weeks before the Absolutist European consortium of troops invaded Spain again, some 15 years after Napoleon invasion, too.

His two sisters were Maria Teresa de Borbón y Vallabriga, also known as María Teresa Carolina de Borbón y Vallabriga, Farnesio y Rozas, 15th Countess of Chinchón since 1803, painted several times by Francisco de Goya who was married in 1797 to Manuel Godoy, and got a daughter, Carlota Manuela de Godoy y Borbón, and Maria Luisa de Borbón y Vallabriga, later First Consort Duchess of San Fernando, a title dating back from 1815, without issue.

Christ on the Mount of Olives: 1819

Goya presented the 'Pious Schools' with another small panel depicting Christ, alone and wracked with doubt, shortly before his arrest. It is a pendant to the large altarpiece (The Last Communion of St Joseph of Calasanz) in which the artist celebrates trust and security.

Count Fernan Nunez: 1803

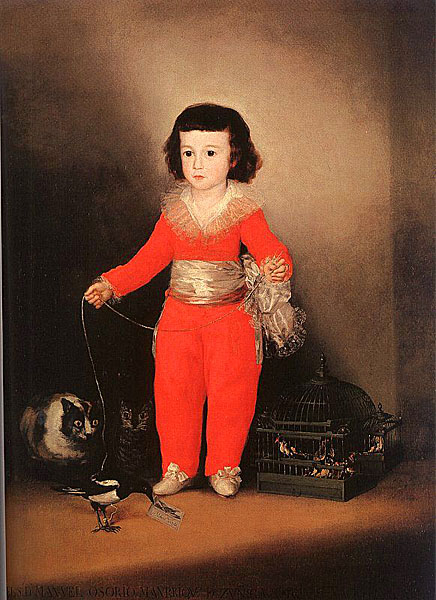

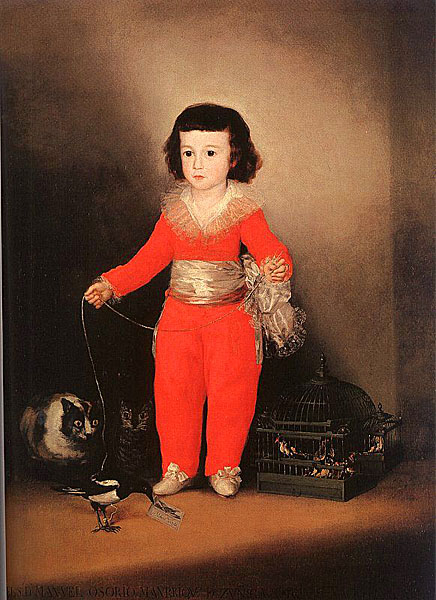

Don Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zuniga

Like Velázquez, Goya was also in demand as a painter of children. After he was appointed Painter to the King of Spain, Charles III, the conde de Altamira commissioned him to paint portraits of his family, including his youngest son, Don Manuel, born in 1784. The fashionably dressed child holds a pet magpie on a string. In the background three cats stare menacingly at the bird, traditionally a symbol of the soul, which gives the painting a sinister and unsettling character. Goya apparently intended this portrait as an illustration of the frail boundaries that separate a child's world from the ever-present forces of evil.

Dona Isabel Cobos de Porcel: 1806

Goya's fame is as ambiguous as his career. A fashionable court painter and society portraitist, once renowned for his designs of light-hearted decorations, he is now celebrated as a passionate denouncer of injustice and the horrors of war. Supreme recorder of his countrymen's diversions, superstitions and travails, he is also the greatest master of private nightmare, expressed above all in the horrific 'Black Paintings' made for his own house. Perhaps the last great artist working in a style associated with 'anciens régimes' throughout Europe, he has been called 'the first of the moderns'.

A painter rivalling Velázquez in the freedom of his brush and his understanding of light and shade, Goya came to be known outside Spain for his engravings, etchings and aquatints, some of the finest ever produced. In a career spanning over sixty years he left some five hundred paintings, most of them still in Spain (where he also executed frescoes), and many more prints and drawings.

Doña Isabel and her husband Don Antonio were close friends of Goya; according to tradition he painted both their portraits during a visit to their home in gratitude for their hospitality. Don Antonio's likeness, formerly in the Jockey Club, Buenos Aires, was subsequently destroyed in a fire.

Doña Isabel wears the dress of a maja - a style originally associated with the demimonde of Madrid, but in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries adopted by ladies of fashion as a token of Spanish patriotism, and also, no doubt, because its black lace mantilla and high waist were madly flattering, as we can see here. The dress justifies the pose, which we know from Flamenco dance: left arm akimbo, torso and head sharply turned in different directions. Perfectly adapted to the half-length format, the protruding right arm and hand providing a stable base for the torso, this pose without the maja connotation would have been unacceptably vulgar in the portrait of a lady. We experience it as wonderfully emancipated.

Goya emphasizes Doña Isabel best features, her eyes and her fresh colouring, without hiding the fleshy nose and slightly underslung jaw; the incipient double chin adds to her youthful charm. Freely painted, the mantilla serves as a dark aureole to her bright face, and tones down the shimmering pink and white bodice in order not to distract from the flesh tones.

Doña Maria Tomasa Palafox Marquesa de Villafranca: 1804

Doña María Tomasa Palafox y Portocarrero, Marchioness of Villafranca was a patron and muse of the painter Francisco de Goya y Lucientes.

In his famous painting, Goya portrays the Marchioness as an artist with brush and maulstick in her hand. She has interrupted her work at the easel and leaning back in her armchair, she is scrutinizing her model, her husband-invisible to the viewer-who is posing for his portrait. He must have been seated facing sideways with his profile to the artist, unable to turn the attention to his wife until the picture was done. Goya honored his aristocratic "colleague" with the inscription of her name on the palette; he himself signed his work with his signature on the arm of the chair. The marchioness, who is fashionably dressed in the Empire style, was certainly more than just a dabbler in art. She was an honorary member of the Madrid Academy, which also honored her with an award.

Ferdinand Guillemardet: 1798

Wearing a tricolour sash, the French Ambassador to Spain poses in Madrid. He represents a new order; in 1793 he voted for the death of King Louis XVI, a cousin of the Spanish monarch.

Festival at the Meadow of San Isadore: ca 1788

This was one of the sketches for a tapestry cartoon that was never executed, due to the death of Charles III, who had commissioned them. It was among the sketches sold to the Duke of Osuna in 1799. The scene represents the most popular festival in the Madrid calendar, which is still celebrated on 15 May, the feast day of the city's patron saint, Isidore the Labourer. In a letter to his friend Zapater in Saragossa, Goya wrote of the difficulties of such a subject especially as he had to finish this painting by the saint's day 'with all the bustle of the court'. It is in fact a rare example of a landscape by Goya, taken from the far side of the Manzanares River with the city's landmarks on the horizon, and in the foreground the crowds amusing themselves as at a fair, the pilgrims hard to distinguish among the animated crowds.

Goya's viewpoint must have been the Hermitage of San Isidro, the goal of the pilgrimage. The building in Goya's painting (also designed as a sketch for a tapestry cartoon), is still preserved, marking the spot where the saint struck a well of water with healing powers. On a tiny scale, Goya has included the pilgrims lining up to enter the church, a picnic scene and a group at the miraculous well. Many years later Goya was to decorate the walls of his country house, the Quinta del Sordo, built not far from the Hermitage, with a nightmare vision of A Pilgrimage to San Isidro.

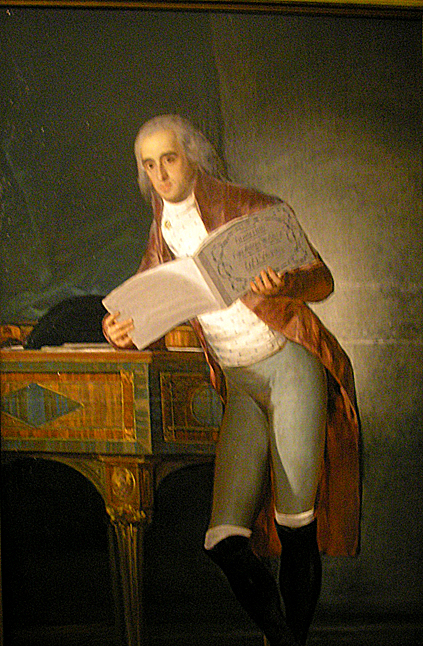

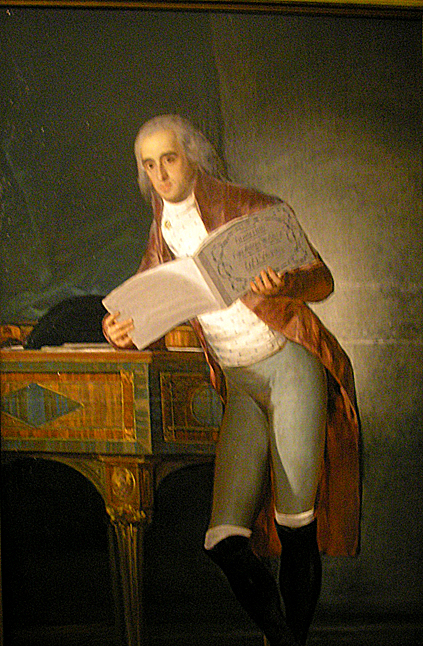

Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos: 1797

Goya painted this grand portrait of his friend and patron Jovellanos (1744-1811), the learned writer and liberal statesman, at the time of his appointment as Minister of Grace and Justice. The liberal patriot and nobleman fought - with increasing success - for reforms and against ignorance, superstition and the Inquisition. The portrait was painted while the court was at Aranjuez.

Not long afterwards Goya painted a portrait of Francisco de Saavedra, Minister of Finance, after he succeeded Godoy as Secretary of State (March 1798), in similar pose. Heroes of a brief liberal interlude, both ministers were soon to be relieved of their posts, victims of Godoy: Jovellanos to become a political prisoner in Mallorca for seven years. Jovellanos, who was 54 years old when he came to power and was painted by Goya, is known to have taken much trouble with his hair, here seen carefully dressed, as he refused to wear a wig. Goya has placed his sitter in a rich setting, with muted lighting, seated in melancholy pose, beside an ornate table covered with papers and with an inkwell. A statue of Minerva in bronze is a tribute to the sitter's great learning and distinguished position at the time of the painting. Jovellanos bequeathed Goya's portrait to his friend and protector, Arias de Saavedra.

Jovellanos as well as Goya used the language of satire to attack social and political abuse. The second of Goya's Caprichos in which a blind-folded young woman is led to the altar by an ugly old man, takes its caption from a verse by his patron: 'They say yes and offer their hand to the first comer.' The Minister's concern for prison reform also found a response in the artist in his many illustrations of the torture of prisoners.

Ramón Satué: 1823

The sitter in this painting has been identified as a nephew of José Duaso y Latre, the clergyman in whose house Goya took shelter in 1823 at the end of the liberal interlude. It has been suggested that the date in the inscription has been altered and that the portrait was painted not later than 1820, the last year in which Satué held office as Alcalde de Corte (a City Councillor of Madrid). From the costume, the informal pose and the style of painting it could have been painted either in 1820 or 1823.

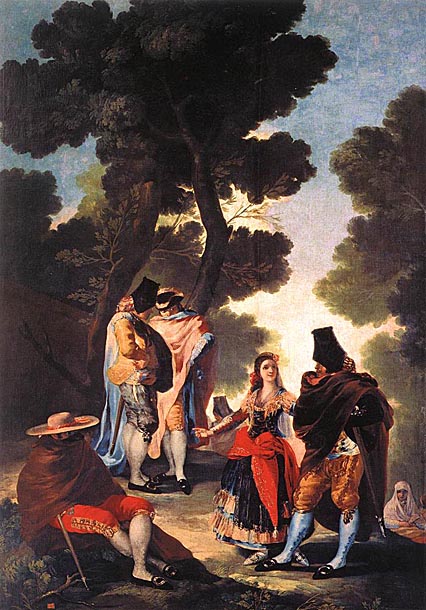

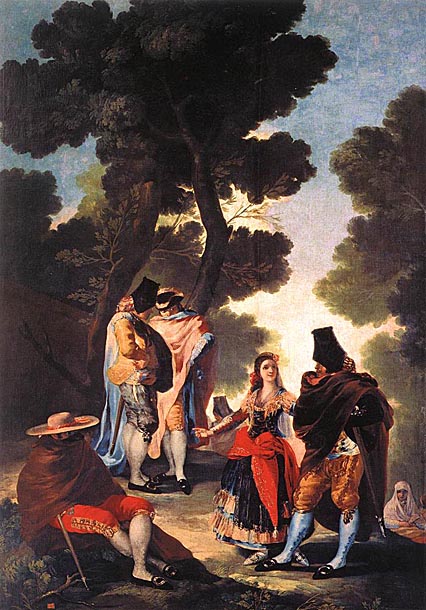

A Walk in Andalusia: 1777

The popular dress worn by 'majos' and 'majas' was thought to have originated amongst the gypsies of southern Spain. Adopted by the people of Madrid at first for May Day festivities, in the 18th century it became a sort of national costume and a form of protest, too, against French influence.

Dance of the Majos at the Banks of Manzanares: 1777

This is one of the tapestry designs commissioned for the royal palaces.

Dona Tadea Arias de Enriquez: 1793

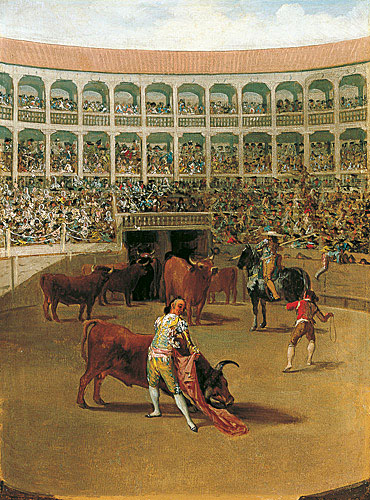

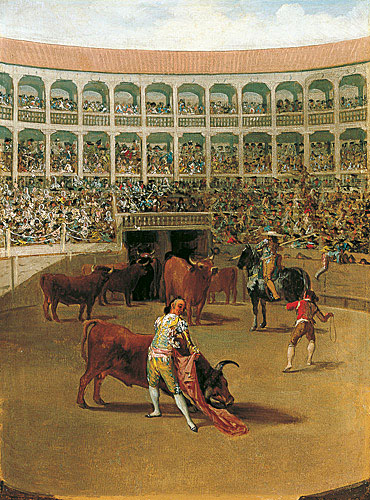

Fight with a Young Bull: 1780

Goya has portrayed himself in this tapestry cartoon. He is said to have spent much time amongst bullfighters in his youth.

Fire at Night: 1793-94

The uncommissioned subjects which Goya painted during his convalescence included not only lunatics in a courtyard, but also fires, shipwrecks and highway robberies. His world was no longer as cheerful and bright as the one he had been required to portray in his tapestry cartoons.

La Tirana: 1799

The painting represents Maria del Rosario Fernández, the famous actress. The title of the painting was originated from the fact that her husband, also an actor, frequently played the role of tyrants.

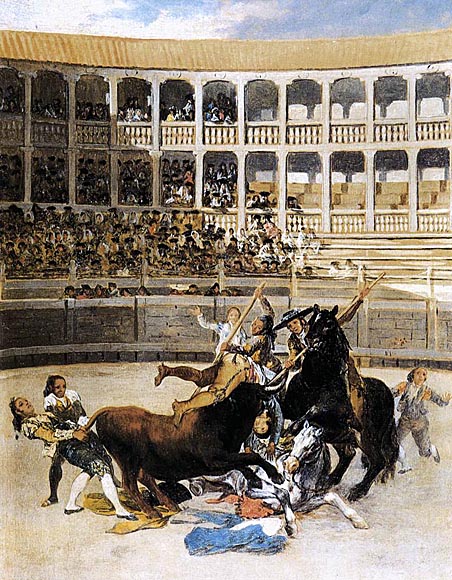

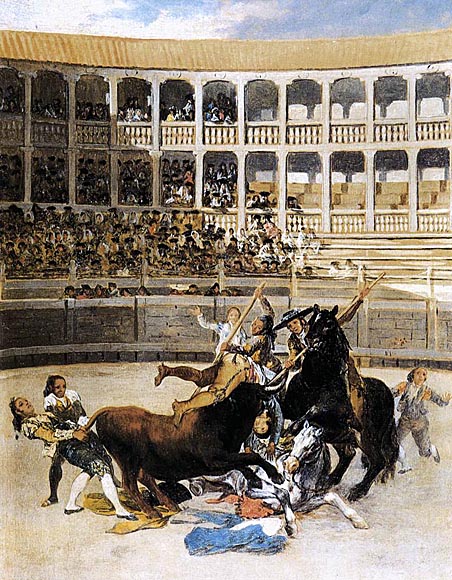

Picador Caught by the Bull: 1793

Goya was fascinated by bullfighting all his life and portrayed himself with a young bull in one of his early tapestry cartoons (Museo del Prado, Madrid). In 1793 he submitted to the Royal Academy eight small paintings of scenes from the life of a bull chosen for the ring.

Picnic: 1788

This is one of the tapestry designs commissioned for the royal palaces. The tapestry was not executed.

Pilgrimage to the Church of San Isidro: 1788

Portrait of Andres del Peral: 1798

According to a modern label on the back of the picture, the sitter was a doctor of law, and financial representative of the Spanish government in Paris at the end of the eighteenth century. He is known to have been a collector and to have owned a number of paintings by Goya.

Goya's friend Carderera commented the painting that Goya 'had such care and love for the grand effect of a picture that he usually put the last touches on by night with artificial light, at times taking little account of whether the drawing was more or less accurate'.

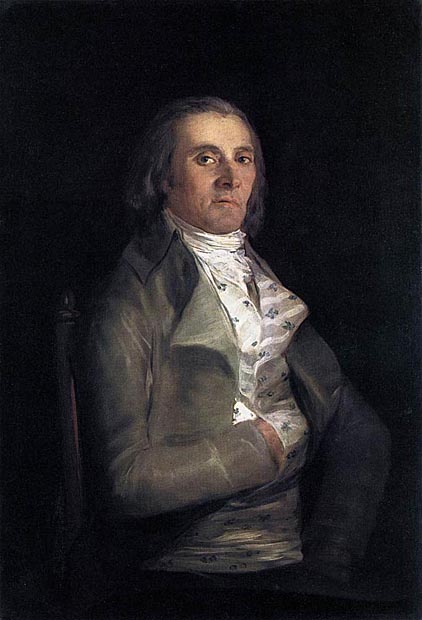

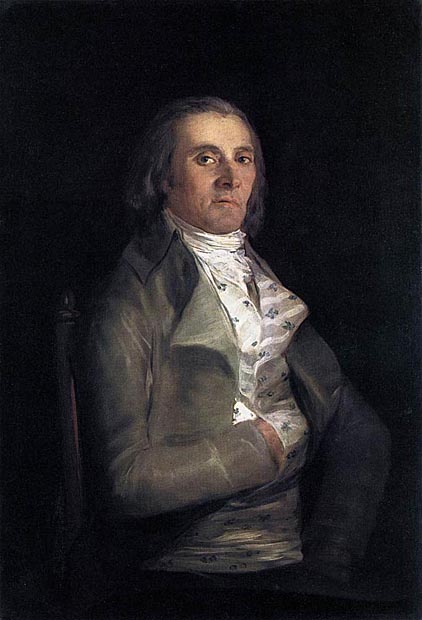

Portrait of Francisco Bayeu: 1795

Goya's portrait of his brother-in-law and former teacher, whom he succeeded as Director of the Academy, was probably painted after Bayeu's death in August 1795. It was unfinished when it was exhibited in the Academy of San Fernando later in the same month. Although this portrait is based on a self-portrait by Bayeu it has all the appearance of a study from life. The predominance of grey and silvery tones is characteristic of a group of Goya's portraits dating from the last years of the eighteenth century. An earlier portrait of Bayeu (1786) by Goya is in the Museo San Pío V, Valencia.

Maria Teresa de Vallabriga on Horseback: 1783

In the summer of 1783 the Infante Don Luis de Borbón, brother of Charles III, invited Goya to stay at his residence of Arena de San Pedro, where the painter executed a series of portraits (possibly sixteen) of Don Luis's family. Goya mentions the equestrian portrait of María Teresa de Vallabriga, the wife of Don Luis, in a letter to his friend Martin Zapater on 2 July 1784.

Although the artist referred to a painting that was unfinished, the reference has been linked to this canvas of the Uffizi.

Evident in this work is Goya's revival and re-adaptation of the 17-century tradition of the equestrian portrait, particularly that of Velázquez.

Portrait of the Countess of Chinchón: 1797-1800

The stunning dress, of a still Tiepolesque lightness, stands out against a timeless, unidentified background; but what really strikes us in this portrait is the totally unidealized face, and the closed, melancholy, uncomprehending expression which verges on idiocy. This is María Teresa de Vallabriga y Borbon, Countess of Chinchón, the daughter of Don Luis de Borbon and María Teresa de Vallabriga, and wife of Manuel Godoy, the favourite of Queen María Luisa.

Portrait of the Wife of Juan Agustin Cean Bermudez: 1785

Juan Agustín Ceán Bermúdez was a Spanish art historian, author of the art encyclopedia published in 1800, which is one of the most important source of the history of Spanish art.

Robbery: 1794

Sebastian Martinez: 1792

This aesthete and art collector, with his cosmopolitan, modern tastes, was a member of the progressive merchant class. Goya stayed in his home in Cadiz during his lengthy illness.

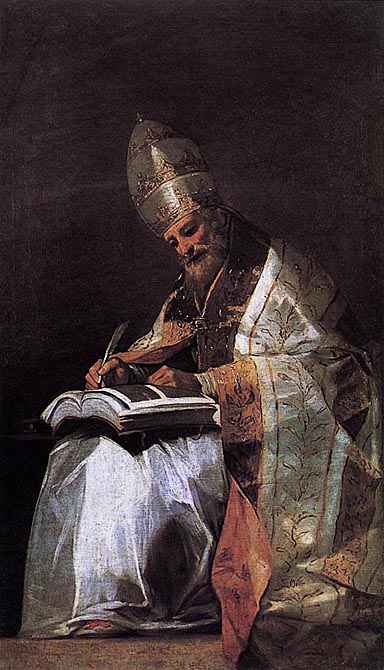

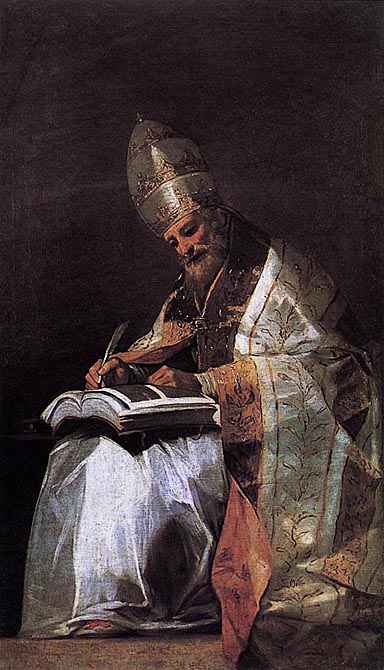

Saint Gregory: 1797

This belongs to a series of representations of the four Doctors of the Church, of which the St Augustine and St Ambrose are also extant. They are not documented but are reasonably assumed to have been painted after Goya's visit to Andalusia in 1796-97 both on stylistic grounds and because of their resemblance to Murillo's seated figures of St Isidore and St Leander in Seville Cathedral. In style and colour they also reflect Goya's earlier studies of Tiepolo.

Goya's St Gregory, seated on a platform like Murillo's saints, is a monumental figure in an undefined space, without decor or attributes other than the large book and papal tiara to identify him as the pope said to have left the greatest number of writings.

The Bewitched Man: 1798

The inscription: LAM/DESCO (Lámpara descomunal, 'extraordinary lamp') identifies the subject as a scene from El hechizado por fuerza ('The man bewitched by force'), a play by Antonio de Zamora. The protagonist, Don Claudio, is led to believe that he is bewitched and that his life depends on keeping a lamp alight. The play was first performed in 1698 and reprinted several times, including 1795, shortly before Goya's painting. Goya has represented the scene as a theatrical performance, on a stage with the dancing donkeys as a backcloth (in the play they are described as paintings on a wall). The goat that appears to hold a lamp is no more than a stage property but the fear that it inspires in Don Claudio is portrayed with dramatic realism.

This was one of six pictures of witches and devils painted by Goya for the Alameda of the Duke and Duchess of Osuna and paid for in 1798. The subjects are similar to scenes of witchcraft in Los Caprichos on which Goya was working at this time.

The Crockery Vendor: 1779

A smart carriage rolls across the marketplace. The men only have eyes for the lady seated inside. Two young women, supervised by an ugly old woman, show off their own charms as they examine the crockery on display.

The Fall (La Caída): 1786-87

La Caída and La Cucana belong to a series of seven paintings of 'country subjects' made to decorate the large gallery in the Duchess of Osuna's apartment in the Alameda Palace, the Osuna country residence outside Madrid known as El Capricho. The paintings were delivered on 22 April 1787. La Caída is described in Goya's account for the paintings submitted on 12 May 1787: 'an excursion in hilly country, with a woman in a faint after a fall from an ass; she is assisted by an abbot and another man who support her in their arms; two other women mounted on asses [and] expressing emotion and another figure of a servant form the main group and others who had fallen behind are seen in the distance, and a landscape to correspond.'

Though on a smaller scale, this series of decorative paintings is similar in style and character to the tapestry cartoons; but unlike the tapestry cartoons it includes some scenes, such as La Caída, which appear to represent actual occurrences. It has been suggested that the fainting woman in La Caída is the Duchess of Osuna, that the figure supporting her is Goya and that the mounted woman weeping is the Duchess of Alba.

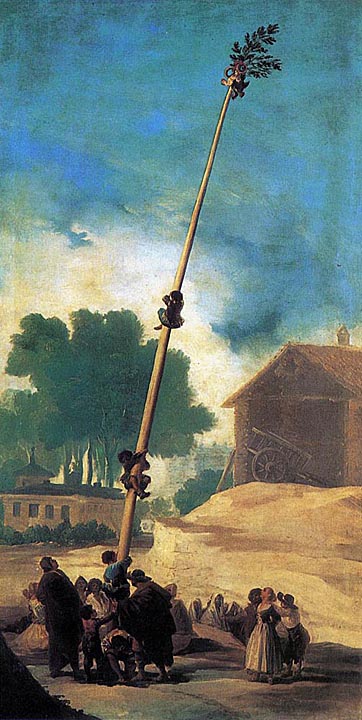

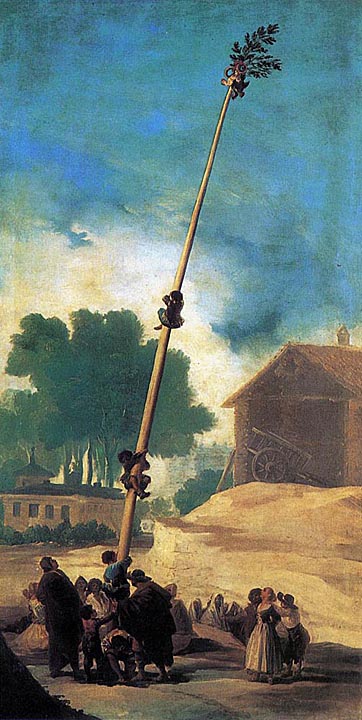

The Greasy Pole (La Cucana): 1786-87

Painted at the same time as La Caída, La Cucana is described in Goya's account: 'a maypole, as in a village square, with boys climbing up it to win a prize of chickens and roscas (ring-shaped biscuits) that are hanging on top, and several people watching, with a background to correspond'. The small scale of the figures in relation to the background is a feature of all the paintings of this series. Later, in 1799, the Duke acquired seven of the sketches for tapestry cartoons that were never executed, to add to the collection of 'country subjects' painted by Goya for his country residence. Goya also painted portraits of the Duke and Duchess and a family group with their children (Museo del Prado, Madrid).

The Countess del Carpio: ca 1793

This picture is considered to be one of Goya's finest female portraits.

Maria Rita Barrenechea y Morante, born in about 1700, married Count del Carpio in November 1775; she died in 1795, and perhaps it is the approach of death which stamps such anxiety on the feverish, languid face, with its great dark eyes. The slender silhouette seems to materialize like a ghost in front of the plain background; in this simple picture, free of all rhetorical devices and exercising a curious fascination by reason of this very simplicity, one finds the strange 'supernatural' quality common to all the masterpieces of Spanish painting. The sylph-like body is only the fleshly covering of a burning spirit. We know that the Countess del Carpio was a cultivated woman; she wrote some poetry which was printed atjaen in 1783.

The pose is a curious one; the position of the feet, one at right angles to the other, suggests that she is about to perform a dance step, but this is belied by the calm and relaxed position of the crossed hands with the fan.

This picture is sometimes called the 'Marquesa de la Solana'; the Count del Carpio only inherited this title a few months before his wife's death. This portrait is usually considered to belong to Goya's 'grey' period, just before the illness (1792) which made him deaf and gave his art a more pathetic quality. This picture is a subtle harmony of greys and black, with a single note of colour — the pink ribbon rosette in the woman's hair.

The Quail Shoot: 1775

The commission to design tapestries for the royal palaces enabled Goya to move to the capital, Madrid. The first series of tapestry cartoons shows hunting scenes, tailored to the interests of the heir to the throne, the later Charles IV.

The Snowstorm: 1786-87

This was one of a series of tapestry cartoons, painted shortly after Goya's appointment as Painter to the King (Pintor del Rey) in 1786. The sketches were submitted to the King at the Escorial in the autumn of that year. The sketch for The Snowstorm was sold to the Duke of Osuna in 1799 as one of the Four Seasons. The cartoon and three others, painted at the same time for tapestries to decorate the dining-room in the Palace of El Pardo, may have been intended as representations of the Seasons. If so, Goya's Winter is unconventional in portraying men enduring the rigours of a snowstorm rather than enjoying the pleasures or comforts of the season.

The Injured Mason: 1786-87

This belongs to the same series of cartoons as The Snowstorm and was also the model for a tapestry to decorate the dining-room in the Palace of El Pardo. The scene of an accident is even more unusual as palace decoration than The Snowstorm or Poor Children at the Fountain, another cartoon in the series. The dramatic subject has been related to an edict of Charles III, first published in 1778, concerning building construction and specifying how scaffolding should be erected 'to avoid accidents and the death of workmen'. In the sketch for the cartoon (also in the Prado), purchased by the Duke of Osuna in 1799, the two men carrying the 'injured' mason have jovial expressions, which have given rise to its modern title The Drunken Mason. Many years later Goya returned to the subject of a building site with elaborate scaffolding, in a drawing now in the Metropolitan Museum.

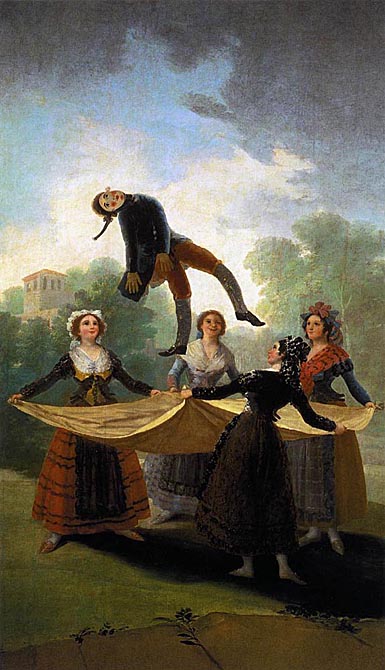

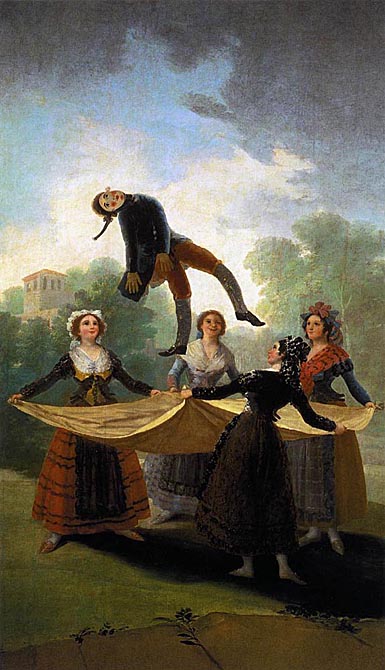

The Straw Manikin: 1791-92

This belongs to Goya's last suite of tapestry cartoons, the only series made for Charles IV after Goya's appointment as Court Painter. The tapestries were to decorate one of the apartments in the Escorial and the subjects, chosen by the King, were to be 'rural and jocose'. Goya had delayed making the sketches as he objected to receiving his instructions from Maella instead of from the Lord Chamberlain. He eventually submitted, since he did not, as he said, want to appear proud. After the naturalism of some of the earlier cartoons, the stiffness of the figures and their artificial expressions come as a surprise. The human figures are as puppet-like as the straw manikin they are tossing in a blanket. A light-hearted carnival tradition here assumes a cruel dimension in a scene that shows what strong women can do with a weak man.

The Wedding: 1791-92

In his later tapestry designs, Goya shows himself unafraid to introduce satire and criticism of the society of the day. With blessing of their families and the Church, an ugly, rich groom is marrying a pretty young bride.

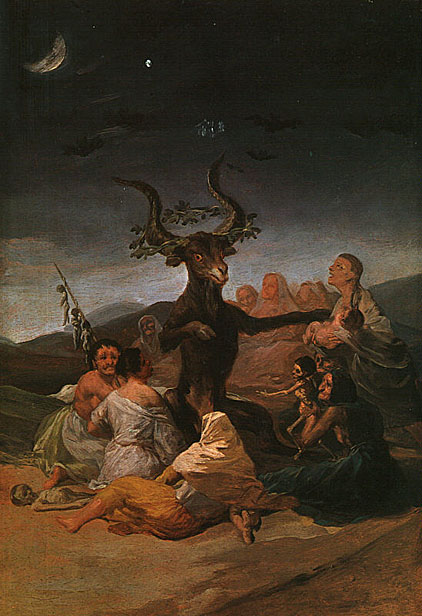

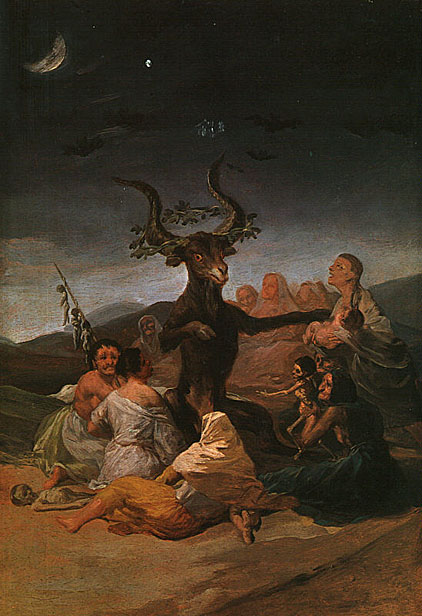

Witches in the Air: 1797-98

Witches are sucking the blood out of the body of someone dead or dying. The man with the cloth over his head is making a sign with his hands to ward off evil spirits.

Quejate al tiempo (Accuse the Time): 1802-11

_1802_11.jpg)

Self Portrait: 1771-75

The painting shows an ambitious young man at the start of his career. He comes from the provinces, from humble circumstances, and is looking for commissions.

Infante Don Sebastian Gabriel de Borbon y Braganza: 1822

The model is the son of Pedro de Borbón and Princess Braganza.

Juan Antonio Llorente: 1810-11

The model, archivist of the Inquisition, wears the Spanish Royal Order, given by Joseph Bonaparte in 1809. He left Madrid in 1812 together with the French.

Knife Grinder: 1808-12

Les Jeunes or the Young Ones: 1812-14

Like many other uncommissioned works, the subject of this painting has been interpreted in various ways and it has borne several descriptive titles. The woman reading the letter has been thought to be a portrait. One critic even suggested that she was the Duchess of Alba (who had died many years before the painting was made), and that she is represented with washerwomen in the background to illustrate a theme of 'Industry and Idleness'. It has also been suggested that Goya intended this painting as a pendant to Time and the Old Women. The two canvases are almost exactly the same size, were acquired for the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lille, at the same time and have the same provenance. But there seems to be no obvious connection between the subjects of the two paintings and Time and the Old Women, which is known to have been in Goya's possession in 1812, is almost certainly a slightly earlier work. There is, in fact, little reason to doubt that the woman reading a letter, standing with her companion and a dog in front of a group of washerwomen, is a genre subject like the earlier tapestry cartoons and other decorative paintings. But the composition is less contrived and, as in many other works, chiefly the uncommissioned ones, it appears to be based on a scene that the artist had witnessed and recorded on the spot or from memory. This was one of four paintings by Goya in the collection of King Louis Philippe which had been obtained in Madrid from Goya's son.

Les Vieilles or Time and the Old Women: 1812-14

The mark 'X23' at the bottom of the canvas identifies this as a painting listed in 1812 in the inventory of paintings in Goya's house allocated to his son Javier. It probably hung next to one or other of two versions of Majas on a Balcony that bears the number X24. The painting of Les Jeunes or the Young Ones (A Woman Reading a Letter), long thought to have been a pendant and later sharing the same history, was possibly intended as such, although painted a year or two later.