1533 - 1603

Regina: 1558 - 1603

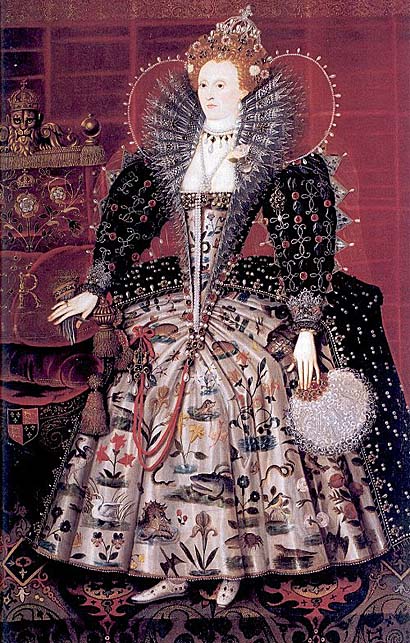

This is the favorite portrait of the queen of many experts and novices including me. It has the most elaborate and inventive style of most any Tudor portrait.

Elizabeth's gown is embroidered with English wildflowers, thus allowing the queen to pose in the guise of Astraea, the virginal heroine of classical literature. Her cloak is decorated with eyes and ears, implying that she sees and hears all. Her headdress is an incredible design decorated lavishly with pearls and rubies and supports her royal crown. The pearls symbolize her virginity; the crown, of course, symbolizes her royalty. Pearls also adorn the transparent veil which hangs over her shoulders. Above her crown is a crescent-shaped jewel which alludes to Cynthia, the goddess of the moon.

A jeweled serpent is entwined along her left arm, and holds from its mouth a heart-shaped ruby. Above its head is a celestial sphere. The serpent symbolizes wisdom; it has captured the ruby, which in turn symbolizes the queen's heart. In other words, the queen's passions are controlled by her wisdom. The celestial sphere echoes this theme; it symbolizes wisdom and the queen's royal command over nature.

Elizabeth's right hand holds a rainbow with the Latin inscription 'Non sine sole iris' ('No rainbow without the sun'). The rainbow symbolizes peace, and the inscription reminds viewers that only the queen's wisdom can ensure peace and prosperity.

Elizabeth was in her late sixties when this portrait was made, but for iconographic purposes she is portrayed as young and beautiful, more than mortal. In this portrait, she is ageless.

Elizabeth I was Queen of England and Queen of Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, The Faerie Queen or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the sixth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty. The daughter of Henry VIII, she was born a princess, but her mother, Anne Boleyn, was executed three years after her birth, and Elizabeth was declared illegitimate. Perhaps for that reason, her brother, Edward VI, cut her out of the succession. His will, however, was set aside, as it contravened the Third Succession Act of 1543, in which Elizabeth was named as successor provided that Mary I of England, Elizabeth's half-sister, should die without issue. In 1558, Elizabeth succeeded her half-sister, during whose reign she had been imprisoned for nearly a year on suspicion of supporting Protestant rebels.

Elizabeth set out to rule by good counsel, and she depended heavily on a group of trusted advisers led by William Cecil, Baron Burghley. One of her first moves was to support the Establishment of an English Protestant Church, of which she became the Supreme Governor. This Elizabethan Religious Settlement held firm throughout her reign and later evolved into today's Church of England. It was expected that Elizabeth would marry, but despite several petitions from parliament, she never did. The reasons for this choice are unknown, and they have been much debated. As she grew older, Elizabeth became famous for her virginity, and a cult grew up around her which was celebrated in the portraits, pageants and literature of the day.

In government, Elizabeth was more conservative than her father and siblings. One of her mottos was Video et Taceo: "I see, and say nothing". This strategy, viewed with impatience by her counselors, often saved her from political and martial alliances that probably would have none more harm than good to her and the nation. Though Elizabeth was cautious in foreign affairs and only half-heartedly supported a number of ineffective, poorly resourced military campaigns in the Netherlands, France and Ireland, the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 associated her name forever with what is popularly viewed as one of the greatest victories in British history. Within twenty years of her death, she was being celebrated as the ruler of a 'Golden Age', an image that retains its hold on the English people. Elizabeth's reign is known as the Elizabethan Era, famous above all for the flourishing of English drama, led by playwrights such as William Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe, and for the seafaring prowess of English adventurers such as Francis Drake and slave-trader John Hawkins.

Historians, however, tend to be more cautious in their assessment. They often depict Elizabeth as a short-tempered, sometimes indecisive ruler, who enjoyed more than her share of luck. Towards the end of her reign, a series of economic and military problems weakened her popularity to the point where many of her subjects were relieved at her death. Elizabeth is however acknowledged by historians as a charismatic leader and an elusive survivor, in an age when government was not unified and limited and when monarchs in neighboring countries faced internal problems that jeopardized their thrones. Such was the case with Elizabeth's rival, Mary, Queen of Scots, whom she imprisoned in 1568 and eventually executed in 1587. After the short reigns of Elizabeth's brother and sister, her forty-five years on the throne provided valuable stability for the kingdom and helped forge a sense of national identity.

Elizabeth was born in Greenwich Palace on September 7, 1533 and named after her paternal grandmother, Elizabeth of York. She was the second legitimate child of Henry VIII of England to survive infancy; her mother was Henry's second wife, Anne Boleyn. At birth, Elizabeth was the heiress presumptive to the throne of England. Her older half-sister, Mary, had lost her position as legitimate heir when Henry annulled his marriage to Mary's mother, Catherine of Aragon, in order to marry Anne. King Henry had desperately wanted a legitimate son, to ensure the Tudor succession. After Elizabeth's birth, Queen Anne failed to provide a male heir. She suffered at least two miscarriages, one in 1534 and another at the beginning of 1536. On May 2, 1536, she was arrested and imprisoned. Hastily convicted on trumped-up charges, she was beheaded on 19 May 1536.

Elizabeth, who was 2 years, 8 months, old at the time, was declared illegitimate and deprived of the title of princess. Eleven days after Anne Boleyn's death, Henry married Jane Seymour, who died twelve days after the birth of their son, Prince Edward. Elizabeth was placed in Edward's household and carried the chrisom, or baptismal cloth, at his christening.

Elizabeth's first governess, Lady Margaret Bryan, wrote that she was "as toward a child and as gentle of conditions as ever I knew any in my life". At the age of four, Elizabeth passed into the care of Catherine Champernowne, better known by her later, married name of Catherine "Kat" Ashley, who remained Elizabeth's friend for life. Champernowne clearly made a good job of Elizabeth's early education: by the time William Grindal became her tutor in 1544, Elizabeth could write English, Latin, and Italian. Under Grindal, a talented and skillful tutor, she also progressed in French and Greek. After Grindal died in 1548, Elizabeth received her education under Roger Ascham, a sympathetic teacher who believed that learning should be fun. By the time her formal education ended in 1550, she was the best educated woman of her generation.

Henry VIII died in 1547, when Elizabeth was 13 years old, and was succeeded by her half brother, Edward VI. Catherine Parr, Henry's last wife, soon married Thomas Seymour of Sudeley, Edward VI's uncle and the brother of the Lord Protector, Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset. The couple took Elizabeth into their household at Chelsea. There Elizabeth experienced an emotional crisis that historians believe affected her for the rest of her life. Seymour approaching forty but with a natural charm and "a powerful sex appeal" engaged in romps and horseplay with the fifteen-year-old Elizabeth. These included entering her bedroom in his nightgown, tickling her and slapping her on the buttocks. This state of affairs was put to a stop by Catherine Parr, after she discovered the pair in an embrace. In May 1548, Elizabeth was sent away.

That was not the last of the matter, however. Seymour was ambitious and scheming to control the royal family. When Catherine Parr died of puerperal fever after childbirth on September 5, 1548, he renewed his attentions towards Elizabeth, intent on wedding her. For his brother and the council, this was the last straw. In January 1549, Seymour was arrested on suspicion of plotting to marry Elizabeth and overthrow his brother. The details of his former behavior towards Elizabeth emerged during an interrogation of Catherine Ashley and Thomas Parry. Elizabeth, living at Hatfield House, would admit nothing. Her stubbornness exasperated her interrogator, Sir Robert Tyrwhitt, who reported, "I do see it in her face that she is guilty". Seymour was beheaded on March 20, 1549. Elizabeth was aged 15 and a half.

'For the face, I grant, I might well blush to offer, but the mind I shall never be ashamed to present. When you shall look on my picture you will witsafe to think that as you have but the outward shadow of the body before you, so my inward mind wisheth that the body itself were oftener in your presence.'

1537 - 1553

Rex: 1547 - 1553

Edward VI died of tuberculosis on 6 July 1553, aged fifteen. His will swept aside the 1543 Act of Succession, excluded both Mary and Elizabeth from the succession, and instead declared as his heir Lady Jane Grey, granddaughter of Henry VIII's sister Mary, Duchess of Suffolk.

The Nine Day Queen

Lady Jane was proclaimed queen, but her support quickly crumbled away, and she was deposed less than two weeks later. Mary rode triumphantly into London, with Elizabeth at her side.

1516 - 1558

Regina: 1553 - 1558

The show of solidarity between the sisters did not last long. Mary was determined to crush the Protestant faith in which Elizabeth had been educated, and she ordered that everyone attend Mass. This included Elizabeth, who had no choice but outwardly to conform. Mary's initial popularity ebbed away when it became known that she planned to marry Prince Philip of Spain, the son of Emperor Charles V. Discontent spread rapidly through the country, and many looked to Elizabeth as a focus for their opposition to Mary's religious policies. In January and February 1554, uprisings broke out (known as Wyatt's Rebellion) in several parts of England and Wales, led by Thomas Wyatt.

Once the rising had collapsed, Elizabeth was brought to court and interrogated. On March 18th , she was imprisoned in the Tower of London, where Lady Jane Grey had been executed on February 12th to deter the rebels. The terrified Elizabeth fervently protested her innocence. Though it is unlikely that she had plotted with the rebels, some of them were known to have approached her. Mary's closest confidant, Charles V's ambassador Simon Renard, argued that her throne would never be safe while Elizabeth lived; and the Chancellor, Stephen Gardiner, worked to have Elizabeth put on trial. However, Elizabeth's supporters in the government, among them Lord Paget, convinced Mary to spare her sister in there was an absence of hard evidence against her. On May 22nd, therefore, Elizabeth was moved from the Tower to Woodstock, where she was to spend almost a year under house arrest in the charge of Sir Henry Bedingfield. Crowds cheered her all along the way.

Written on a Wall at Woodstock

By Elizabeth Tudor

Oh Fortune, thy wresting wavering state

Hath fraught with cares my troubled wit,

Whose witness this present prison late

Could bear, where once was joy's loan quit.

Thou causedst the guilty to be loosed

From bands where innocents were inclosed,

And caused the guiltless to be reserved,

And freed those that death had well deserved.

But all herein can be nothing wrought,

So God send to my foes all they have thought.

On 17 April 1555, Elizabeth was recalled to court to be closely attended during the final stages of Mary's apparent pregnancy. If Mary and her child died, Elizabeth would become queen. If, on the other hand, Mary gave birth to a healthy child, Elizabeth's chances of becoming queen would recede sharply. When it became clear that Mary was not pregnant, no one believed any longer that she could have a child. Elizabeth's succession seemed assured. Even Philip, who became King of Spain in 1556, acknowledged the new political reality. From this time forward, he cultivated Elizabeth, preferring her to the likely alternative, Mary, Queen of Scots, who was betrothed to the Dauphin of France. When his wife fell ill in 1558, Philip sent the Count of Feria to consult with Elizabeth. By October, Elizabeth was making plans for her government. On 6 November, Mary recognized Elizabeth as her heir.

News of Mary's death on November 17, 1558 reached Elizabeth at Hatfield, where she was said to be out in the park, sitting under an oak tree. Upon hearing that she was Queen, legend has it that Elizabeth quoted the 118th Psalm's twenty-third line, in Latin: "A Dominum factum est illud, et est mirabile in oculis notris" ~ "It is the Lord's doing, and it is marvelous in our eyes."

Elizabeth became queen at the age of twenty-five. As her triumphal progress wound through the city on the eve of the coronation ceremony, she was welcomed wholeheartedly by the citizens and greeted by orations and pageants, most with a strong Protestant flavor. Elizabeth's open and gracious responses endeared her to the spectators, who were "wonderfully ravished". The following day, January 15, 1559, Elizabeth was crowned at Westminster Abbey and anointed by the Catholic Bishop of Carlisle. Then she was presented for the people's acceptance, amidst a deafening noise of organs, fifes, trumpets, drums, and bells.

On November 20, 1558, Elizabeth declared her intentions to her Council and other peers who had come to Hatfield to swear allegiance. The speech contains the first record of her often-used metaphor of the "two bodies": the body natural and the body politic:

Elizabeth was in no doubt that her most powerful lords wished her to repudiate the Pope and Spanish influence. This chimed with her own conscience and the policies of Sir William Cecil, her Secretary of State, and her chief advisors. She also knew that the Papacy would never recognize her as the legitimate child of Henry VIII and the rightful ruler of England. She therefore determined to establish a Protestant Church suited to the needs of the English people. As a result, the parliament of 1559 legislated for a Church based on the Settlement of Edward VI, with the monarch as its head. The House of Commons backed the proposals strongly, but the bill of supremacy met opposition in the House of Lords, particularly from the Bishops. Elizabeth was fortunate, however, that many bishoprics were vacant at the time, including the Archbishopric of Canterbury. This enabled the Protestant peers to outvote the bishops and conservative peers.

After various negotiations and changes to the wording, the new Act of Supremacy became law on May 8, 1559. Elizabeth's title was agreed to be Supreme Governor of the Church of England rather than the more contentious Supreme Head. All public officials were to swear an oath of loyalty to the monarch as the supreme governor or risk disqualification from office; however, the heresy laws were repealed, to avoid a repeat of the persecution of dissenters practiced by Mary. At the same time, a new Act of Uniformity was passed, which made attendance at church and the use of an adapted version of the 1552 Book of Common Prayer compulsory, though the penalties for disobedience were not extreme.

Many Catholics, particularly on the continent, regarded Elizabeth as nothing more than an illegitimate heretic. In 1570, Pope Pius V excommunicated her, calling her the "pretended queen of England". This sanction, which in theory released English Catholics from allegiance to Elizabeth, served only to identify the English Church more closely with the crown. It also placed English Catholics in great danger. By encouraging them to rebel, it raised doubts about their loyalty to the queen.

From the start of Elizabeth's reign, the question arose of who she would marry. However, she never married, and the reasons for this are not clear. Historians have speculated that Thomas Seymour had put her off sexual relationships, or that she knew herself to be infertile. Until bearing a child became impossible, she considered several suitors, the last courtship ending in 1581 when she was aged 48, François, Duke of Anjou (22 years her junior). However, Elizabeth had no need of a man's help to govern, and marrying risked a loss of control or of foreign interference in her affairs, as had happened to her sister Mary. On the other hand, marriage offered the chance of an heir.

Elizabeth often received offers of marriage, but she only seriously considered three or four suitors for any length of time. Of these, her childhood friend Robert Dudley probably came closest. During 1559, Elizabeth's friendship with the married Dudley seems to have turned to love. Rumor spread through the court that she was sleeping with him; William Cecil, Elizabeth's most trusted advisor, made clear his disapproval. When Dudley's wife, Amy Robsart, was found dead in 1560, uncertainly of natural causes, and under suspicious circumstances, a great scandal arose. For a time, Elizabeth seriously considered marrying Dudley; but after several months, she put duty ahead of her feelings and decided against the marriage. Dudley, whom she made Earl of Leicester and appointed to the Privy Council, retained a special place in her heart, though her infatuation mellowed in time to a special and lasting friendship. After Elizabeth died, a note from Dudley, who had died in 1588, was found among her possessions, marked "his last letter".

After the Dudley affair, Elizabeth kept the marriage question open but often only as a diplomatic ploy. She appears to have considered marriage out of duty rather than personal preference. Parliament repeatedly petitioned her to marry, but she always answered evasively. In 1563, she told an imperial envoy: "If I follow the inclination of my nature, it is this: beggar-woman and single, far rather than queen and married". In the same year, following Elizabeth's illness with smallpox, the succession question became a heated issue. Parliament urged the queen to marry or nominate an heir, to prevent a civil war upon her death. She refused to do either. In April, she prorogued the Parliament, which did not reconvene until she needed its support to raise taxes in 1566. The House of Commons threatened to withhold funds until she agreed to provide for the succession. In 1566, Sir Robert Bell boldly pursued the issue despite Elizabeth's command to desist and became the target of her anger "in her own words: 'Mr. Bell with his complices must needs prefer their speeches to the upper house to have you my lords, consent with them, whereby you were seduced, and of simplicity did assent unto it'."

In 1566, she confided to the Spanish ambassador that if she could find a way to settle the succession without marrying, she would do so. By 1570, senior figures in the government privately accepted that Elizabeth would never marry or name a successor. William Cecil was already seeking solutions to the succession problem. For this stance, as for her failure to marry, she was often accused of irresponsibility. However, Elizabeth's silence strengthened her own political security: she knew that if she named an heir, her throne would be vulnerable to a coup.

Elizabeth's unmarried status inspired a cult of virginity. In poetry and portraiture, she was depicted as a virgin or a goddess or both, not as a normal woman. At first, only Elizabeth made a virtue of her virginity: in 1559, she told the Commons, "And, in the end, this shall be for me sufficient, that a marble stone shall declare that a queen, having reigned such a time, lived and died a virgin". Later on, particularly after 1578, poets and writers took up the theme and turned it into an iconography that exalted Elizabeth. In an age of metaphors and conceits, she was portrayed as married to her kingdom and subjects, under divine protection. In 1599, Elizabeth spoke of "all my husbands, my good people".

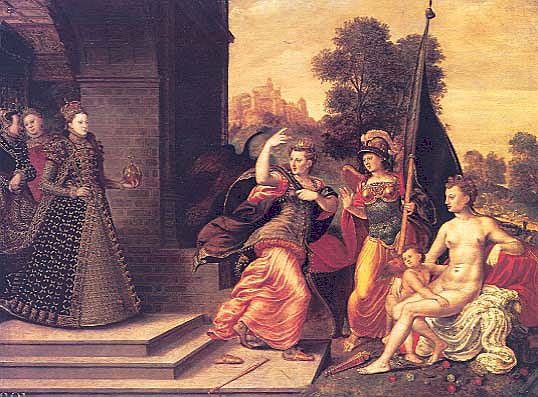

The figure to the right of Elizabeth is possibly her courtier Sir Christopher Hatton. His white hind badge is just barely visible on the figure's cloak. If so, then it is possible that Hatton commissioned this portrait; he may have met Metsys during a trip to Antwerp in 1573.

The roundels behind the queen depict the story of Aeneas and Dido, with the queen compared to Aeneas. Like the classical hero, she has faced temptation (marriage) and now leads a powerful nation. The globe behind the queen continues this theme. Ships are crossing west on the globe, possibly an allusion to England's conquest of the New World. TVTTO VEDO ET MOLTO MANCHA ('I see all and much is lacking') is inscribed on the globe. The portrait itself is inscribed: STANCHO RIPOSO & RIPO SATO AFFA NNO ('Weary I am and, having rested, still am weary.')

ON MONSIEUR'S DEPARTURE

By Elizabeth I, Queen of England

I grieve and dare not show my discontent,

I love and yet am forced to seem to hate,

I do, yet dare not say I ever meant,

I seem stark mute but inwardly do prate.

I am and not, I freeze and yet am burned,

Since from myself another self I turned.

My care is like my shadow in the sun,

Follows me flying, flies when I pursue it,

Stands and lies by me, doth what I have done.

His too familiar care doth make me rue it.

No means I find to rid him from my breast,

Till by the end of things it be supprest.

Some gentler passion slide into my mind,

For I am soft and made of melting snow;

Or be more cruel, love, and so be kind.

Let me or float or sink, be high or low.

Or let me live with some more sweet content,

Or die and so forget what love ere meant.

THE DOUBT OF FUTURE FOES

By Queen Elizabeth I

The doubt of future foes exiles my present joy,

And wit me warns to shun such snares as threaten mine annoy;

For falsehood now doth flow, and subjects' faith doth ebb,

Which should not be if reason ruled or wisdom weaved the web.

But clouds of joy untried do cloak aspiring minds,

Which turn to rain of late repent by changed course of winds.

The top of hope supposed the root upreared shall be,

And fruitless all their grafted guile, as shortly ye shall see.

The dazzled eyes with pride, which great ambition blinds,

Shall be unsealed by worthy wights whose foresight falsehood finds.

The daughter of debate that discord aye doth sow

Shall reap no gain where former rule still peace hath taught to know.

No foreign banished wight shall anchor in this port;

Our realm brooks not seditious sects, let them elsewhere resort.

My rusty sword through rest shall first his edge employ

To poll their tops that seek such change or gape for future joy.

Apart from the Dudley affair, Elizabeth treated the marriage issue as an aspect of foreign policy. Though she turned down Philip II's own offer in 1559, she negotiated for several years to marry his cousin Archduke Charles of Austria. However, relations with the Habsburgs deteriorated by 1568. Elizabeth then considered marriage to two French Valois princes in turn, first Henri, Duke of Anjou, and later, from 1572 to 1581, his brother François, Duke of Anjou. This last proposal was tied to a planned alliance against Spanish control of the Southern Netherlands. Elizabeth seems to have taken the courtship seriously for a time. She even wore a frog-shaped earring that Anjou had sent her.

Elizabeth's foreign policy was largely defensive. The exception was the disastrous occupation of Le Havre from October 1562 to June 1563, when Elizabeth's Huguenot allies joined with the Catholics to retake the port. Elizabeth had intended to exchange Le Havre for Calais, retaken by France in January 1558. She sent troops into Scotland in 1560 to prevent the French using it as a base. In 1585, she signed the Treaty of Nonsuch with the Dutch to block the Spanish threat to England. Only through the activities of her fleets did Elizabeth pursue an aggressive policy. This paid off in the war against Spain, 80 per cent of which was fought at sea. She knighted Francis Drake after his circumnavigation of the globe from 1577 to 1580, and he won fame for his raids on Spanish ports and fleets. Her reign also saw the first colonization or "planting" of new land in North America; and the colony of Virginia was named for her. In truth, however, an element of piracy and self-enrichment drove Elizabethan Seafarers, over which the queen had little control.

Elizabeth's first policy toward Scotland was to oppose the French presence there. She feared that the French planned to invade England and put Mary, Queen of Scots, who was in effect the heir to the English crown, on the throne. Elizabeth was persuaded to send a force into Scotland to aid the Protestant rebels, and though the campaign was inept, the resulting Treaty of Edinburgh of July 1560 removed the French threat in the north. When Mary returned to Scotland in 1561 to take up the reins of power, the country had an established Protestant church and was run by a council of Protestant nobles supported by Elizabeth. Mary refused to ratify the treaty.

Elizabeth offended Mary by proposing her own former suitor, Robert Dudley, as a husband. Instead, in 1565 Mary married Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, who carried his own claim to the English throne. The marriage, however, was the first of a series of errors of judgment by Mary that handed the victory to the Scottish Protestants and to Elizabeth. Darnley quickly became unpopular in Scotland and then infamous for presiding over the murder of Mary's Italian secretary David Rizzio. In February 1567, Darnley was murdered by conspirators almost certainly led by James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell. Shortly afterwards, on May 15, 1567, Mary married Bothwell, arousing suspicions that she had been party to the murder of her husband. Elizabeth wrote to her:

"How could a worse choice be made for your honor than in such haste to marry such a subject, who besides other and notorious lacks, public fame has charged with the murder of your late husband, besides the touching of yourself also in some part, though we trust in that behalf falsely."

These events led rapidly to Mary's defeat and imprisonment in Loch Leven Castle. The Scottish lords forced her to abdicate in favor of her son James, who had been born in June 1566. James was taken to Stirling Castle to be raised as a Protestant. Mary escaped from Loch Leven in 1568 but after another defeat fled across the border into England, where she had once been assured of support from Elizabeth. Elizabeth's first instinct was to restore her fellow monarch; but she and her council instead chose to play safe. Rather than risk returning Mary to Scotland with an English army or sending her to France and the Catholic enemies of England, they detained her in England. She was imprisoned there for the next nineteen years.

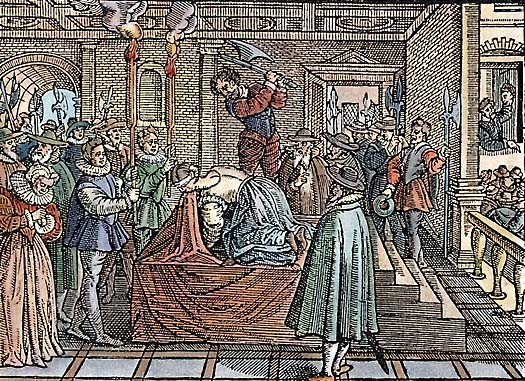

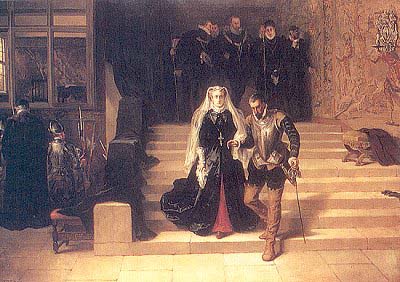

Mary was soon the focus for rebellion. In 1569, plotters in the Rising of the North talked of freeing her, and a scheme arose to marry her to Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk. Elizabeth reacted by sending Howard to the block. Mary may not have been told of every Catholic plot to put her on the English throne, but from the Ridolfi Plot of 1571 to the Babington Plot of 1586, Elizabeth's spymaster Sir Francis Walsingham and the royal council keenly assembled a case against her. At first, Elizabeth resisted calls for Mary's death. By late 1586, however, she had been persuaded to sanction her trial and execution on the evidence of letters written during the Babington Plot. Elizabeth's proclamation of the sentence announced that "...the said Mary, pretending title to the same Crown, had compassed and imagined within the same realm divers things tending to the hurt, death and destruction of our royal person...". On February 8, 1587, Mary was beheaded at Fotheringhay Castle, Northamptonshire.

Mary comforted her weeping servants, her friends and supporters to the last. They helped her undress; beneath her all-black gown, she wore a red petticoat and bodice. Her women helped her attach the long red sleeves. Mary thus died wearing the liturgical color of Catholic martyrdom. She gave them her golden rosary and Agnus Dei, asking them to remember her in their prayers. Her eyes were covered with a white cloth. While her servants wept and called out prayers in a medley of languages, she laid her neck upon the block, commended herself to God and received the death-stroke. But the executioner was unsteady and the first blow cut the back of her head; Mary whispered, 'Sweet Jesus', and the second blow descended.

When the executioner lifted her head and cried out, 'God save the Queen,' a macabre surprise occurred. Mary, queen of Scots had worn an auburn wig to her execution. It was left in the executioner's hand as her head, with its short, grey hair, fell to the floor.

After the disastrous occupation and loss of Le Havre in 1562-1563, Elizabeth avoided military expeditions on the continent until 1585. In that year, she sent an English army to aid the Protestant Dutch rebels against Philip II. This followed the deaths in 1584 of the allies William the Silent, Prince of Orange, and François, Duke of Anjou, and the surrender of a series of Dutch towns to Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma, Philip's governor of the Spanish Netherlands. In December 1584, an alliance between Philip II and the French Catholic League at Joinville undermined the ability of Anjou's brother, Henry III of France, to counter Spanish domination of the Netherlands. It also extended Spanish influence along the channel coast of France, where the Catholic League was strong and exposed England to invasion. The English and the Dutch reacted in August 1585 with the Treaty of Nonsuch, whereby Elizabeth, pressured by her advisors, promised military support to the Dutch. The treaty marked the beginning of the Anglo-Spanish War, which lasted until the Treaty of London in 1604.

Elizabeth did not trust this course of action from the start. The expedition, led by her old flame, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, achieved nothing. Elizabeth's strategy, to use the English army as a defensive bargaining tool, was soon at odds with that of Dudley, who wanted to fight an active campaign but lacked the resources to do so. He enraged Elizabeth by accepting the post of Governor-General from the Dutch States-General. Elizabeth saw this as a Dutch ploy to embroil her further in their defense.

She wrote to him: "We could never have imagined (had we not seen it fall out in experience) that a man raised up by our self and extraordinarily favored by us, above any other subject of this land, would have in so contemptible a sort broken our commandment in a cause that so greatly touches us in honor....And therefore our express pleasure and commandment is that, all delays and excuses laid apart, you do presently upon the duty of your allegiance obey and fulfill whatsoever the bearer hereof shall direct you to do in our name. Whereof fail you not, as you will answer the contrary at your utmost peril."

Elizabeth and her parliament's failure to send Dudley sufficient money and troops, combined with his own incompetence as a military leader, doomed the campaign to impotence. Dudley finally resigned his command in December 1587, his reputation in tatters. By that time, Philip II had decided to take the war to England.

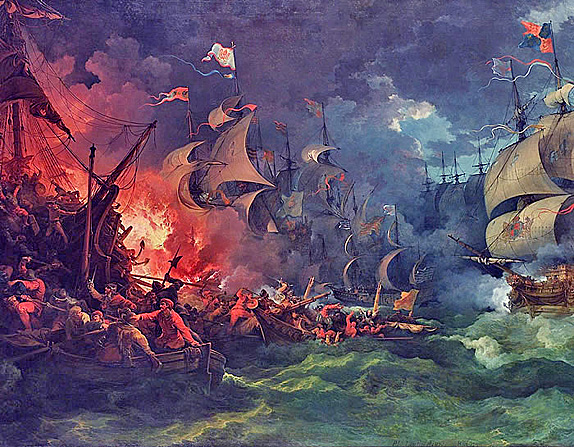

On July 12, 1588, the Spanish Armada, a great fleet of ships, set sail for the channel, planning to ferry a Spanish invasion force under the Duke of Parma to the coast of southeast England from the Netherlands. The Armada, however, was defeated by a combination of miscalculation, misfortune, and an attack of English fire ships on July 29th off Gravelines which dispersed the Spanish ships to the northeast. The Armada straggled home to Spain in shattered remnants, after disastrous losses on the coast of Ireland (after some ships had tried to struggle back to Spain via the North Sea, and then back south past the west coast of Ireland). Unaware of the Armada's fate, English forces mustered to defend the country. Elizabeth inspected her troops at Tilbury in Essex on August 8th. Wearing a silver breastplate over a white velvet dress, she addressed them in one of her most famous speeches:

"My loving people, we have been persuaded by some that are careful of our safety, to take heed how we commit ourselves to armed multitudes for fear of treachery; but I assure you, I do not desire to live to distrust my faithful and loving people....I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a King of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any Prince of Europe should dare to invade the borders of my realm."

When no invasion came, the nation rejoiced. Elizabeth's procession to a thanksgiving service at Saint Paul's Cathedral rivaled that of her coronation as a spectacle. The defeat of the Armada was a potent propaganda victory, both for Elizabeth and for Protestant England. The English took their delivery as a symbol of God's favor and of the nation's inviolability under a virgin queen. However, the victory was not a turning point in the war, which continued and often favored Spain. The Spanish still controlled the Netherlands, and the threat of invasion remained. Sir Walter Raleigh claimed after her death that Elizabeth's caution had impeded the war against Spain:

"If the late queen would have believed her men of war as she did her scribes, we had in her time beaten that great empire in pieces and made their kings of figs and oranges as in old times. But her Majesty did all by halves, and by petty invasions taught the Spaniard how to defend himself, and to see his own weakness."

Though some historians have criticized Elizabeth on similar grounds, Raleigh's verdict has more often been judged unfair. Elizabeth had good reason not to place too much trust in her commanders, who once in action tended, as she put it herself, "to be transported with a Behavior of Vainglory".

In 1587, a year before this portrait was made, the first English child was born at the English settlement in Virginia. The crown and globe tell us that Elizabeth is mistress of land and sea.

In the background of the painting are scenes from the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588. It was the pivotal event of the latter half of Elizabeth's reign and a great triumph for the English.

The queen is wearing a pearl necklace given to her by the earl of Leicester; it was Robert Dudley's last gift to the queen.

In 1592, Elizabeth's former champion, Sir Henry Lee, sought to regain her favor with lavish entertainment at his home in Ditchley, Oxfordshire. He had retired from court two years earlier, having offended the queen by living openly with his mistress. He commissioned this portrait to commemorate Elizabeth's visit and forgiveness. The Queen stands upon a map of England, with one foot resting near Ditchley.

The sonnet on the 'Ditchley Portrait' lacks the final word of each line. It celebrates Elizabeth's divine powers; a jeweled celestial sphere hangs from the queen's left ear, signifying her command over nature itself. The sphere had been Lee's emblem when he fought as Elizabeth's champion in the annual Accession Day tilts. The background of this portrait appears odd - it is split between blue and sunny sky on the left, and black and stormy sky on the right. This continues the theme of royal authority over nature.

Tudor / Renaissance fashion buffs should note that the queen wears her lovely gown over a wheel farthingale. This style briefly continued after Elizabeth's death, largely because James I's wife, Anne of Denmark, wore some of Elizabeth's gowns in portraits painted by, among others, Gheeraerts.

Return to Persona Historiae

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.