American Painter and Sculptor

1864 - 1926

Charles Marion Russell, also known as C. M. Russell, was an artist of the American West. Russell created more than 2,000 paintings of cowboys, Indians, and landscapes set in the Western United States, in addition to bronze sculptures. Russell was also a storyteller and author. The C. M. Russell Museum Complex is located in his hometown of Great Falls, Montana houses more than 2,000 Russell artworks, personal objects, and artifacts.

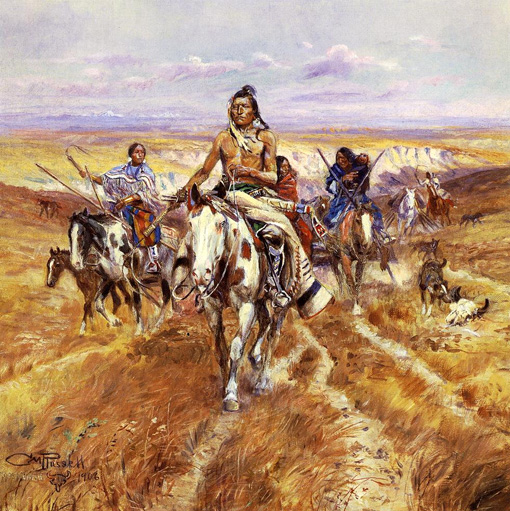

Russell's mural entitled Lewis and Clark Meeting the Flathead Indians hangs in the state capitol building in Helena, Montana. Russell's 1918 painting Piegans sold for $5.6 million dollars at a 2005 auction.

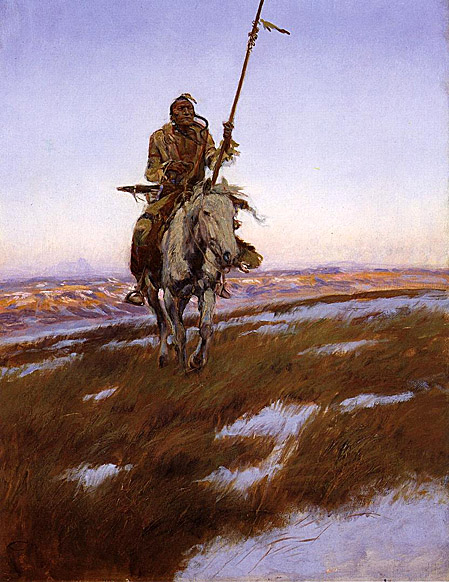

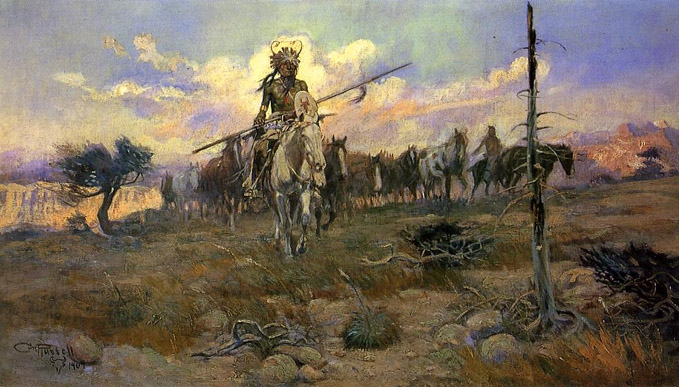

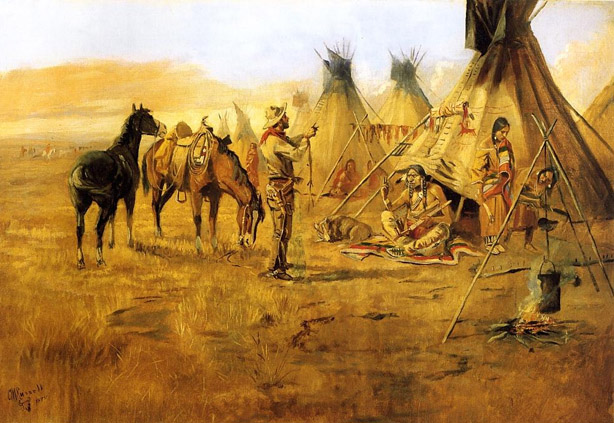

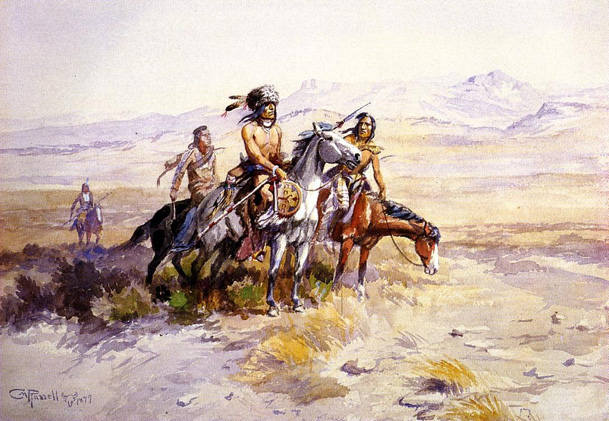

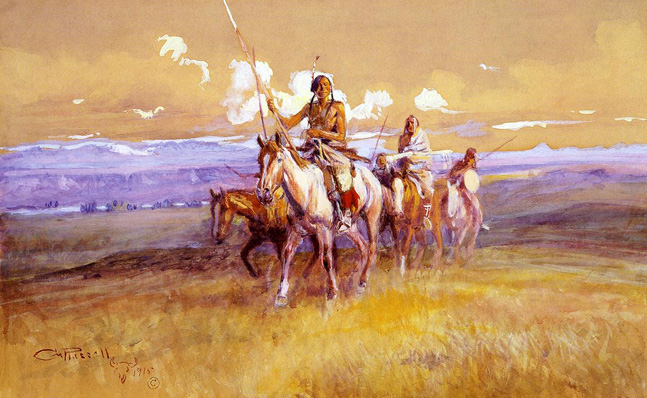

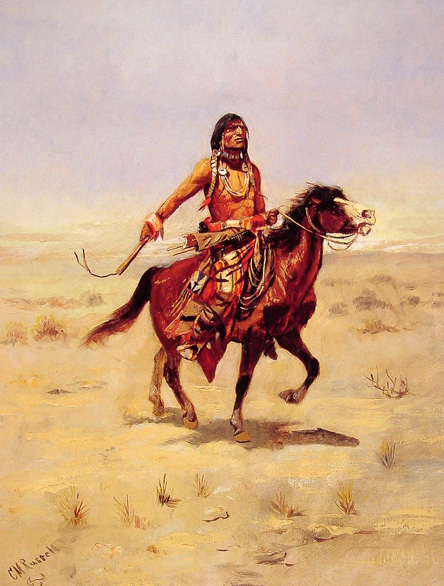

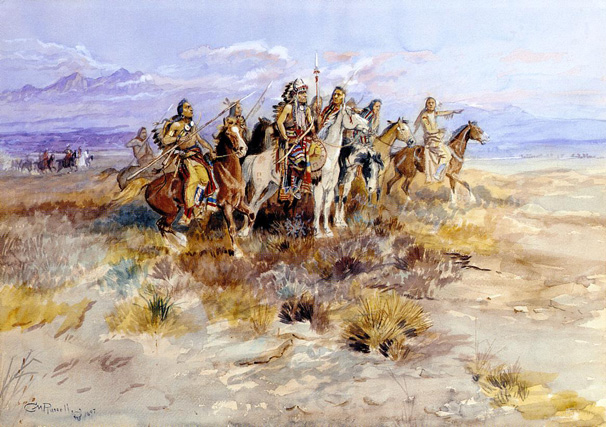

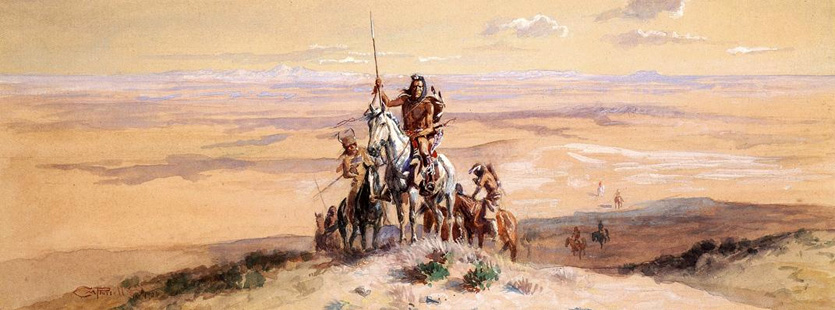

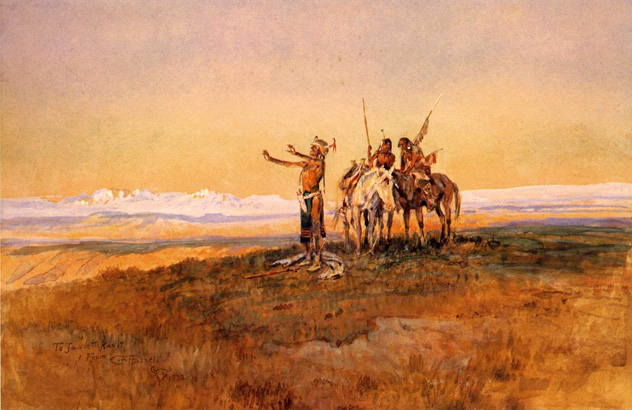

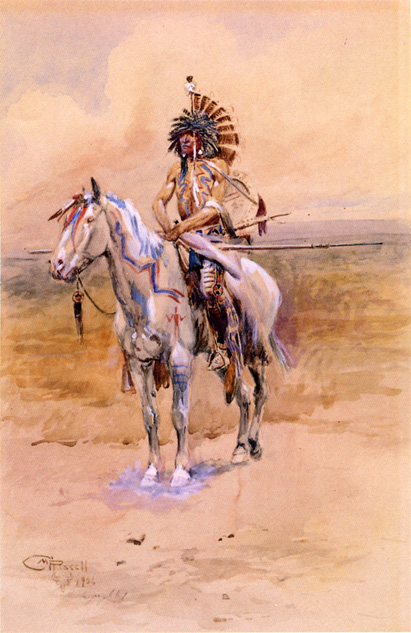

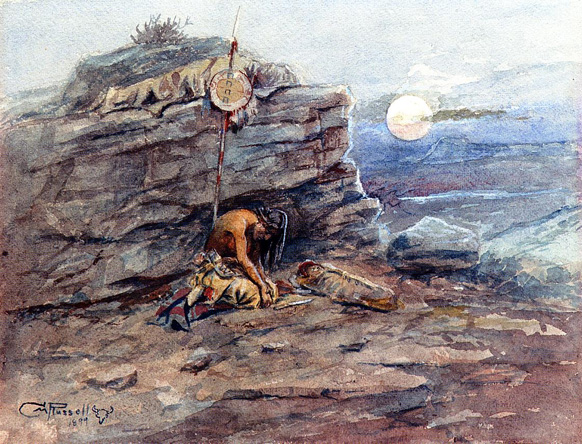

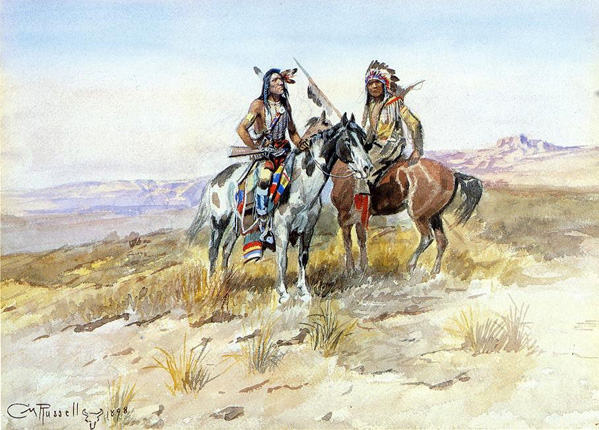

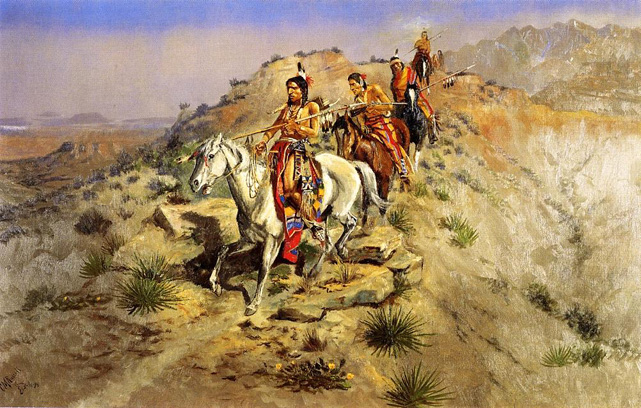

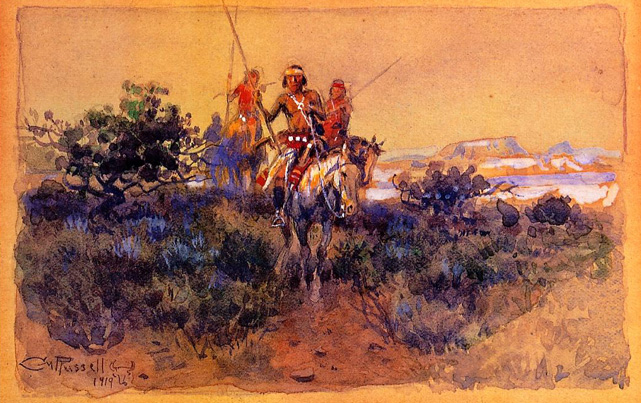

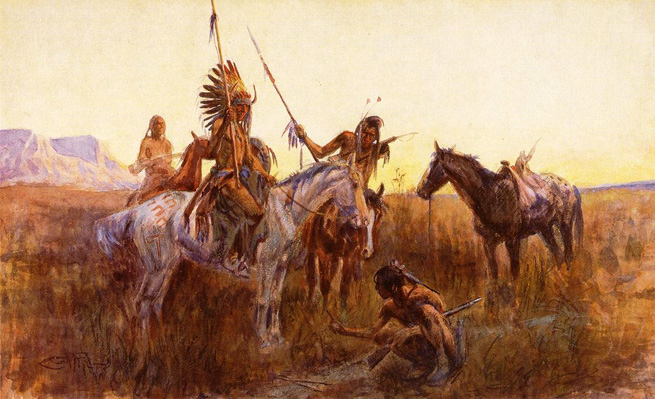

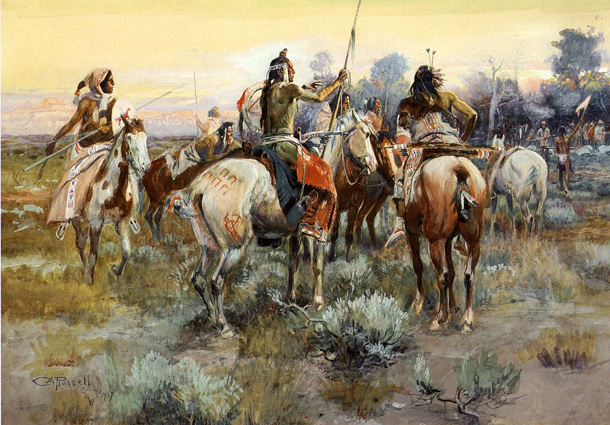

Russell had spent the winter of 1887-1888 with the Blood Indians, another Blackfoot tribe, on the Canadian border, and in 'The Piegans Preparing to Steal Horses' from the Crows he accurately depicts their pipes, coup sticks, feathers and bone ornaments, and the red-earth paint on their faces. Plains Indian culture was highly regimented, with a complex system of honors and sacred symbols obtained in dreams and activated by use and red-earth "seven paint", which gave order to their nomadic life as hunters. The modesty and mobility of their sacred objects reflected, as Ralph T. Coe observed, their "fragile relationship with space, the creator, and with their disciplined world". It was a relationship that captured the imagination of the young artist. His sensitivity to Blackfoot spiritual life is evident here as he shows the warriors' ritual preparation for the raid. As an early observer reported, "Each serious act was preceded by formal smoking."

The figures of the Indians and horses are carefully rendered and stand out in sharp focus against the thinly painted background, producing areas of abruptly ambiguous space (not unlike Degas' landscapes) charged with a feeling of impermanence. Russell was self-taught and his work always reflected the conceptual, linear touch of the primitive, but rarely to such expressive effect as here. The handling of light and color is also remarkably subtle, particularly in the delicate tones of the sky and the touches of red against the dark landscape.

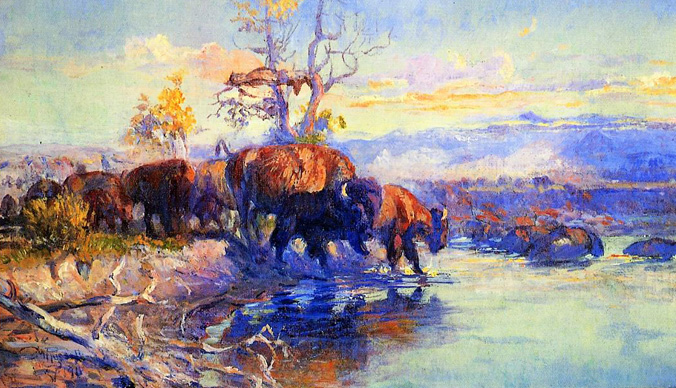

Russell inscribed the painting with the buffalo skull, which appears in many of his early works. It was an ironic symbol, for it suggested not only the destruction of the vast herds that formed the basis of Plains Indian life and freedom but the eventual disappearance of the open range that had drawn him West in 1880.

Art was always a part of Russell's life. Growing up in Missouri, he drew sketches and made clay figures of animals. Russell had an intense interest in the Wild West and would spend hours reading about it. Russell would watch explorers and fur traders who frequently came through Missouri. Russell learned to ride horses at Hazel Dell Farm in Jerseyville, Illinois on a famous Civil War horse called "Great Britain". Russell's instructor was Col. William H. Fulkerson who had married into the Russell family. At the age of sixteen, Russell left school and went to Montana to work on a sheep ranch.

Russell returned to Missouri and Illinois in the winter of 1882 to visit family. Russell's cousin James Fulkerson, nine months younger, was persuaded to join Russell working on a Montana cattle ranch. However as Russell later wrote his cousin "died of mountain fever at Billings two weeks after we arrived" on 27 May 1883.

In 1882, by the age of eighteen, Russell was working as a cattle hand. The harsh winter of 1886 and 1887 provided the inspiration for a painting that would give Russell his first taste of publicity. According to stories, Russell was working on the O-H Ranch in the Judith Basin of Central Montana when the ranch foreman received a letter from the owner, asking how the cattle herd had weathered the winter. Instead of a letter, the ranch foreman sent a postcard-sized watercolor Russell had painted of gaunt steer being watched by wolves under a gray winter sky. The ranch owner showed the postcard to friends and business acquaintances and eventually displayed it in a shop window in Helena, Montana. After this, work began to come steadily to the artist. Russell's caption on the sketch, "Waiting for a Chinook", became the title of the drawing, and Russell later created a more detailed version which is one of his best-known works.

In 1896, Russell married his wife Nancy. In 1897, they moved from the small community of Cascade, Montana to neighboring Great Falls, where Russell spent the majority of his life from that point on. There, Russell continued with his art, becoming a local celebrity and gaining the acclaim of critics worldwide. As Russell kept primarily to himself, Nancy is generally given credit in making Russell an internationally known artist. She set up many shows for Russell throughout the United States and in London creating many followers of Russell's.

Russell the artist arrived on the cultural scene at a time when the "Wild West" was being chronicled and sold back to the public in many forms, ranging from the dime novel to the Wild West show and soon evolving into motion picture shorts and features of the silent era, the westerns that have become a movie staple. Russell was fond of these popular art forms, and made many friends among the well-off collectors of his works, including actors and film makers such as William S. Hart, Harry Carey, Will Rogers and Douglas Fairbanks. Russell also kept up with other artists of his ilk, including painter Edward "Ed" Borein and Will Crawford the illustrator.

On the day of Russell's funeral in 1926, all the children in Great Falls were released from school to watch the funeral procession. Russell's coffin was displayed in a glass sided coach, pulled by four black horses.

A collection of short stories called Trails Plowed Under was published a year after his death. Also, in 1929, Russell's wife, Nancy, published a collection of his letters in which was titled Good Medicine.

From: Charles M. Russell

"Between the pen and the brush there is little difference but I believe the man that makes word pictures is the greater."

Charles M. Russell - Letter to Ralph S. Kendall, November 26, 1919

Charles Marion Russell was an accomplished painter, sculptor, illustrator, and a gifted storyteller. Russell was born on March 19, 1864 in St. Louis, Missouri on the edge of the burgeoning Western frontier. As a boy, he crafted his own expectations of the American West by filling his schoolbooks with drawings of cowboys and Indians. Shortly before turning 16, he arrived in Montana where he spent eleven years working various ranching jobs. He sketched in his free time and soon gained a local reputation as an artist. His firsthand experience as a ranch hand and his intimate knowledge of outdoor life contributed to the distinctive realism characteristic of his style.

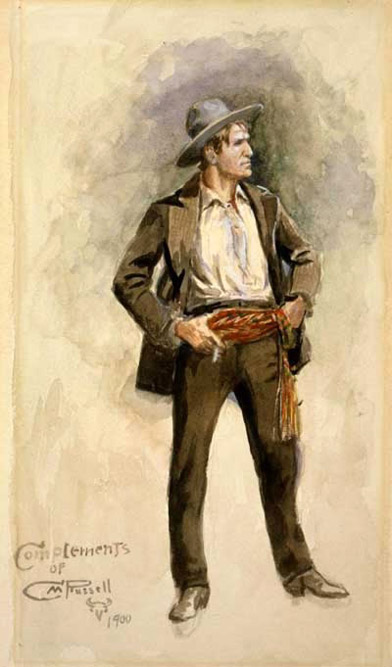

In his Self-Portrait, painted in 1900, Russell stands with his feet planted solidly and his hat tipped back, he portrays himself as a stalwart yet open person. He wears the red Metis sash and custom made high-heeled riding boots that were a mark of his individuality, just as much as his quick wit, laconic speech, and gift as a raconteur - exhibited in his humorous short stories, and illustrated letters. Russell wrote, "I am old-fashioned and peculiar in my dress. I am eccentric (that is a polite way of saying you're crazy). I believe in luck and have lots of it...Any man that can make a living doing what he likes is lucky, and I'm that." Considered a sensitive, modest and unassuming man, Russell simply saw his great talent as merely "luck."

In September 1896, he married Nancy Cooper, who became his business manager. Under her support and guidance, Russell gained national recognition and successfully marketed his art. Russell learned from observation, and his art improved dramatically after 1903 when he and Nancy began making regular visits to New York. It was here that Russell began working with a group of experienced illustrators, where he enjoyed being part of an artistic community - something he lacked back home in Montana.

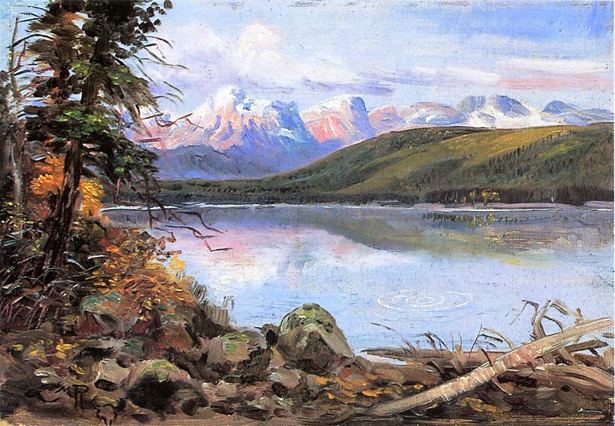

Russell painted and sculpted in his log studio adjacent to their Great Falls home, filling it with his vast collection of Native American and cowboy objects. Russell completed all of his major paintings in the studio after it was constructed in 1903. Having the talent to successfully work in many mediums, Russell created whimsical wax animals and clay and plaster figures, but he also made more formal sculptures, many of which were cast in bronze. Russell enjoyed modeling animal figures on oddly shaped roots or branch fragments. Mountain Mother captures the playful nature of the cubs and the watchful, protective instinct of the sow.

Painting in a time when there was considerable interest in the West, Russell's works were popular because of their narrative subject matter, unique style, and dynamic action. In addition, he had the ability to paint fictional history.

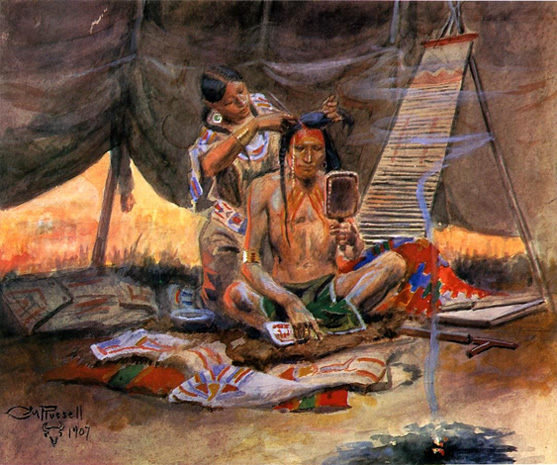

American Indian women played important roles in a number of Russell paintings, such as 'Indian Women Moving Camp', and he produced several versions of the subject. The seasonal rounds of Plains tribes provided the artist with the opportunity of depicting the Indian women proudly riding on horseback. He used a compositional group placed at a slight diagonal to the picture plane that is similar to his subject of Indian warriors. Thus he accords the same dignity to the women's work and reveals his admiration for the resourcefulness, independence, and courage of Plains Indian women.

Russell was one of the few artists of the American West to actively paint the daily life of Native American women. John C. Ewers, the noted ethnologist who studied the Blackfoot tribe, noted that a normal day's march was about ten to fifteen miles, and the average family of eight (two males, three females, and three children) required at least ten horses to move their camp efficiently. Prior to the arrival of horses on the northern plains in the mid-eighteenth century, dogs were used as the primary mode of transport. The wolf like dogs depicted in this painting were often used as guards once the camp had settled for the night. Unlike other plains tribes, the Blackfeet refused to eat dog meat.

Charlie Russell became not only the favorite son of his home state of Montana, but also the personification of the West itself. He wanted little to do with the present and nothing to do with the future, and chose to celebrate and romanticize only the traditions and virtues of the West as he envisioned it. He wanted it known that he had taken part in the Old West, and was a better man for it. Even as an internationally known western artist, Russell cherished - far more than his skills - his friendships and his place as a peer among common people.

Russell completed approximately 4,000 artworks during his lifetime. Living 46 years in the West, he knew his subject matter intimately, setting the standard for many western artists to follow. Charles M. Russell died in Great Falls, Montana on October 24, 1926.

Charles Russell was William E. Weiss's (1913-1985) favorite artist, and he appreciated Russell's dedication to preserving the Old West. Mr. Weiss' many special gifts of Russell artwork can be enjoyed in the Charles M. Russell Wing of the Whitney Gallery of Western Art.

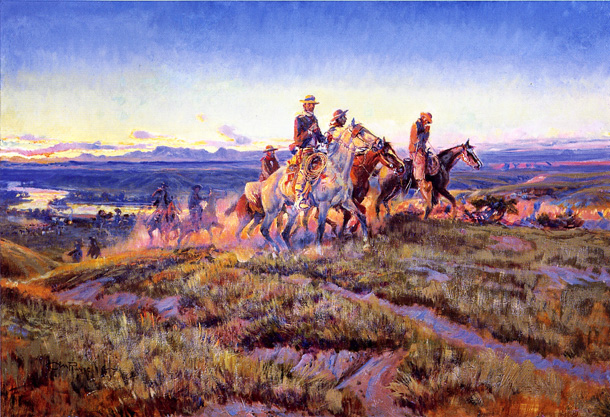

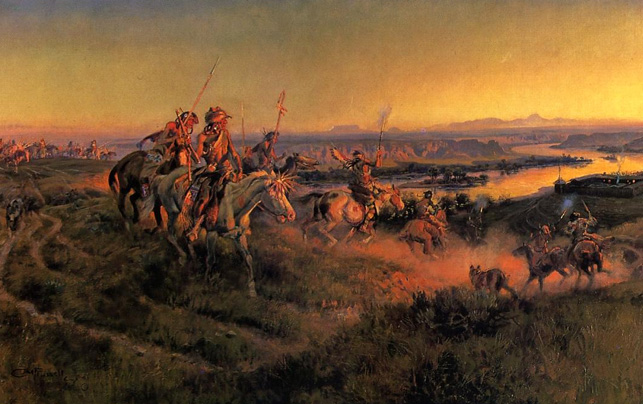

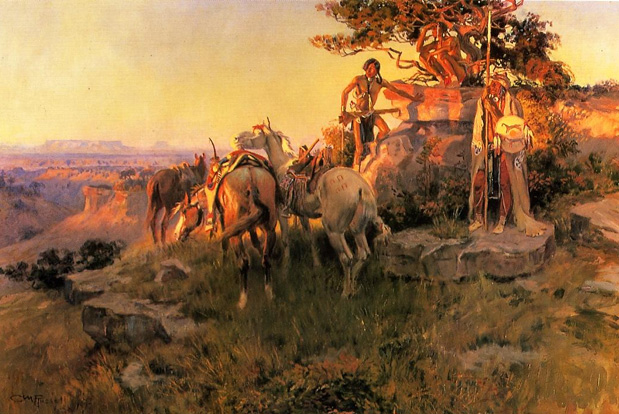

Here Russell depicted one of those battles, between a group of men with pack animals and a band of hostile Blackfeet. The men are surrounded, and some are using the bodies of their fallen horses as defensive breastworks. A Blackfoot lies dead in the left foreground, while the other members of his party circle in the distance. Russell created a tight central composition in the classic "last stand" mode, which owed much to the published visual representations of the defeat of General George A. Custer at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in July 1876. A man in the very center of Russell's painting aims his rifle across the flanks of his horse directly at the viewer-placing the viewer, as Russell often did, on the side of the Indians.

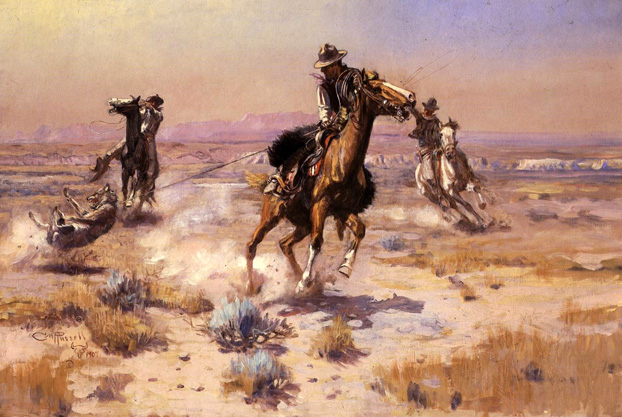

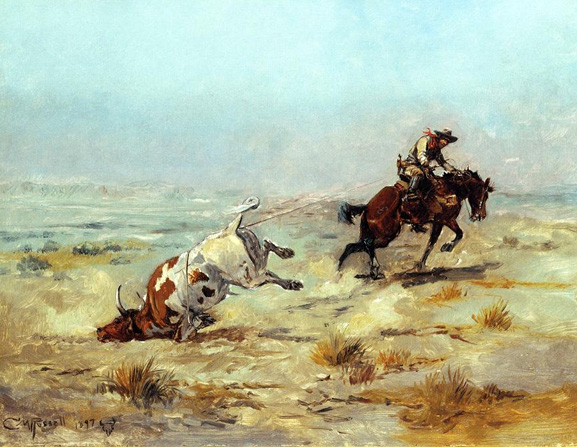

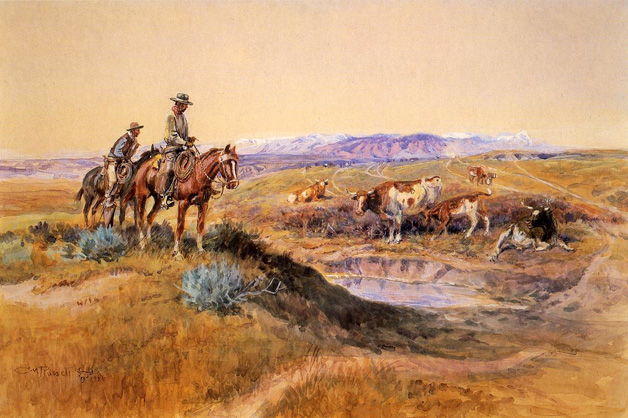

When Russell painted this scene, the great buffalo herds had only recently been eliminated from the northern prairies, and the open-range cattle industry was flourishing on lands that had been ceded by the Indian tribes. This painting depicts the rich grasslands north and west of the Judith River, where Russell first worked as a night herder and horse wrangler. The cowboys and their recalcitrant mounts are a type that Russell would later make famous in his works. It is interesting to note that only American cowboys customarily carried six-shooters, as they are doing in Russell's painting. Canadian riders rarely did so, and the Mexican vaqueros considered the practice unmanly. But research has shown that few American cowboys seem to have carried their weapons during the roundups, as Russell shows here, because they were mostly unnecessary for the work at hand.

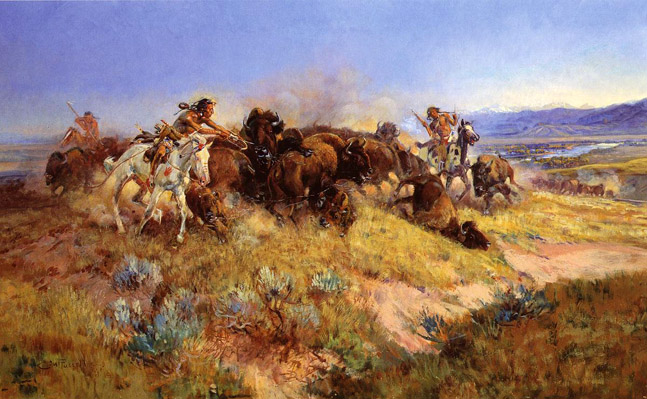

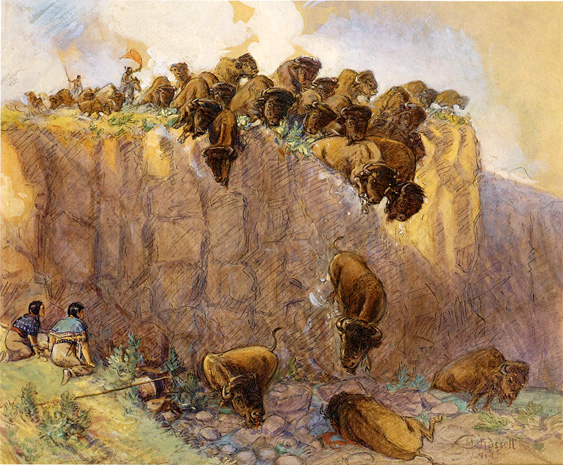

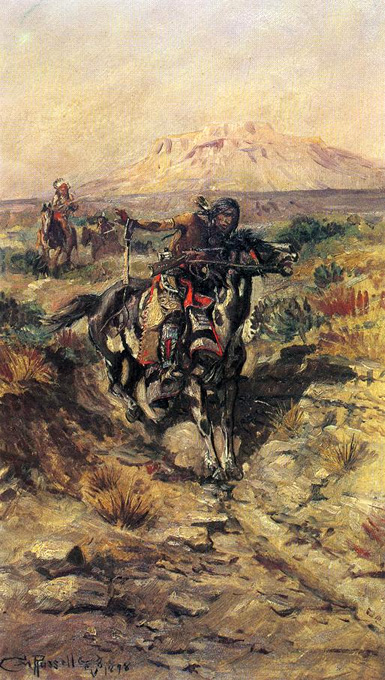

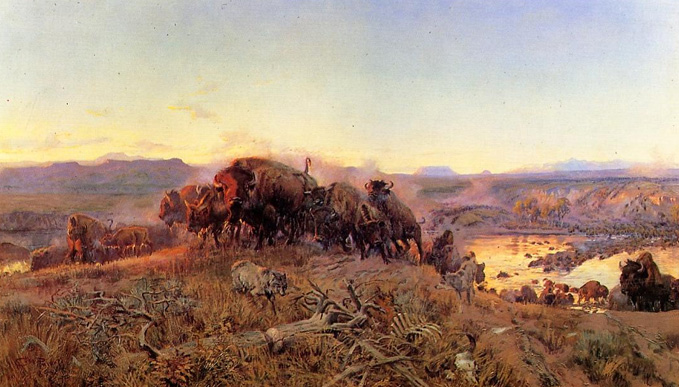

Throughout his life Russell painted more than fifty versions of the subject of the buffalo hunt, and both the artist and his wife, Nancy, regarded this particular example as one of his finest efforts. As in his earlier versions of the subject, Russell concentrated on the moment when the mounted Indian hunters overtake a stampeding band of buffalo from opposite directions, forcing the animals to tumble over each other in panic and allowing the warriors to close in and pick off the cows or calves. Russell arranged the figures in a tight composition that occupies center stage in the broad Sun River landscape, with the blue-shouldered outline of Square Butte in the background. A Blackfoot warrior, his face and arms decorated with red paint, drives his arrows into a cow that has just trampled her calf. The Indian's white horse is brightly decorated; a feather has been tied to its tail as a talisman. According to some Indian sources of the day, the red handprint visible on the horse's neck was an indication that the warrior had "ridden over an enemy" in battle.

In this painting the Blackfoot Hunters, having cut off part of the herd, are attacking from two directions to force the frightened animals to turn into each other-a technique that minimized the danger of any riders or their horses being gored or trampled in the ensuing melee. On the left, a highly-trained "buffalo horse" surges up to the right of one animal and, in Catlin's words, gives the rider the chance "to throw the arrow to the left, which he does at the instant the horse is passing-bringing him opposite the heart, which receives the deadly weapon." On the right, a mounted warrior is set to drive his lance into another beast, which turns in desperation into the seething group. Although Russell's depiction seems to be fairly accurate. Later Blackfoot commentators maintained that the riders always used saddles for greater safety.

_1913.jpg)

_1905.jpg)

_1893.jpg)

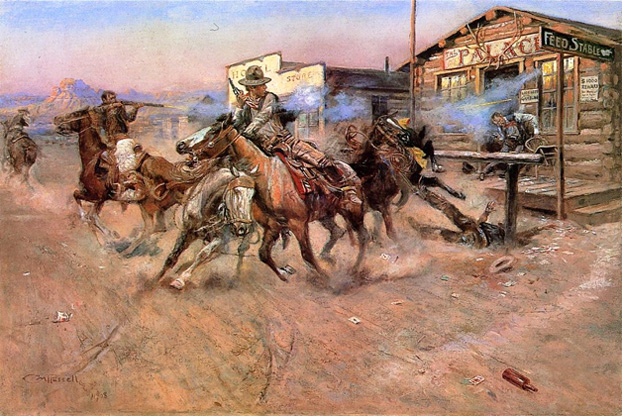

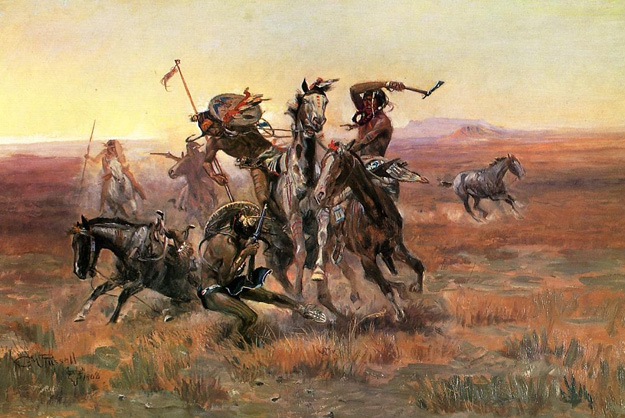

This painting, a spirited depiction of a fracas between a group of cowboys and the inhabitants of a gambling saloon on the Montana frontier, attracted much attention when it was exhibited in Chicago and New York in 1911. The painting was originally created for the Ridgley Calendar Company, who exhibited it in their office window in Great Falls in February 1908 before shipping it out for reproduction. Russell's abilities as a painter and storyteller are readily apparent in this work. The composition of interwoven men and horses sweeps the eye from right to left and back again as the action reaches its crescendo. Blue smoke from the gunfire lingers in the air between the protagonists; the frantic horses lurch in opposite directions, but also in perfect visual counterpoint. Here Russell manages to compress a great amount of detail into a seamless story line. On the right side of the painting, a string of playing cards lies strewn upon the ground, giving mute testimony to the wages of sin.

Source: Art Renewal Center

Source: Charles M. Russell Online

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.