German Romantic Painter, Etcher, Watercolorist & Draftsman

1774 - 1840

Caspar David Friedrich was a landscape painter of the nineteenth-century German Romantic Movement, of which he is now considered the most important painter. A painter and draughtsman, Friedrich is best known for his later allegorical landscapes, which feature contemplative figures silhouetted against night skies, morning mists, barren trees, and Gothic ruins. His primary interest as an artist was the contemplation of nature, and his often symbolic and anti-classical work seeks to convey the spiritual experiences of life.

Friedrich was born in Greifswald in northern Germany in 1774. He studied in Copenhagen until 1798 before settling in Dresden. He came of age during a period when, across Europe, a growing disillusionment with an over-materialistic society led to a new appreciation for spiritualism. This was often expressed through a reevaluation of the natural world, as artists such as Friedrich, J. M. W. Turner and John Constable sought to depict nature as a "divine creation, to be set against the artifice of human civilization".

Although Friedrich was renowned during his lifetime, his work fell from favor during the second half of the nineteenth century. As Germany moved towards modernization, a new urgency was brought to its art, and Friedrich's contemplative depictions of stillness were seen as the products of a bygone age. His rediscovery began in 1906 when an exhibition of 32 of his paintings and sculptures was held in Berlin. During the 1920's his work was appreciated by the Expressionists, and in the 1930's and 1940's, the Surrealists and Existentialists frequently drew on his work. Today he is seen as an icon of the German Romantic Movement, and a painter of international importance.

Caspar David Friedrich was born the sixth of ten children in Greifswald, Swedish Pomerania, on the Baltic Sea. He grew up under the strict Lutheran creed of his father Adolf Gottlieb, a prosperous candle-maker and soap boiler. Friedrich had an early familiarity with death: his mother, Sophie Dorothea Bechly, died in 1781 when Caspar David was just seven. At the age of thirteen, Caspar David witnessed his brother, Johann Christoffer, fall through the ice of a frozen lake and drown. Some accounts suggest that Johann Christoffer succumbed while trying to rescue Caspar David, who was also in danger on the ice. His sister Elisabeth died in 1782, while a second sister, Maria, succumbed to typhus in 1791.

Some of Friedrich's contemporaries attributed the melancholy in his art to these childhood events, yet it is as likely that Friedrich's personality was naturally so inclined. As an adult, the pale and withdrawn Friedrich reinforced the popular notion of the "taciturn man from the North". His letters, however, always contained humor and self-irony. In his autobiography, the natural philosopher Gotthilf Heinrich von Schubert wrote of Friedrich, "He was indeed a strange mixture of temperament, his moods ranging from the gravest seriousness to the gayest humor … But anyone who knew only this side of Friedrich's personality, namely his deep melancholic seriousness, only knew half the man. I have met few people who have such a gift for telling jokes and such a sense of fun as he did, providing that he was in the company of people he liked."

In 1790, Friedrich began to study art with Johann Gottfried Quistorp at the University of Greifswald, and literature and aesthetics with the Swedish professor Thomas Thorild. Thorild was interested in the contemporary English aesthetic, and taught Friedrich to distinguish between the spiritual 'inner eye' and the less favorable physical 'outer eye'. Friedrich entered the prestigious Academy of Copenhagen in 1794 where he studied under teachers such as Christian August Lorentzen and the landscape painter Jens Juel. These artists were inspired by the Sturm und Drang movement, and represented a midpoint between the dramatic intensity and expressive manner of the budding Romantic aesthetic and the by then waning neo-classical form. Mood was paramount, and influence was drawn from such sources as the Icelandic legend of Edda and Ossian, and Nordic Folklore. A talented student, Friedrich began his education at the academy by making copies of casts from antique sculptures, before proceeding to drawing from life. He was keenly interested in seventeenth-century Dutch landscape painting, to which he had access at Copenhagen's Royal Picture Gallery.

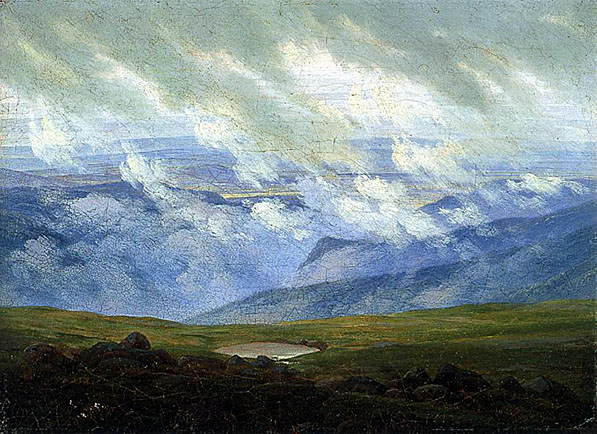

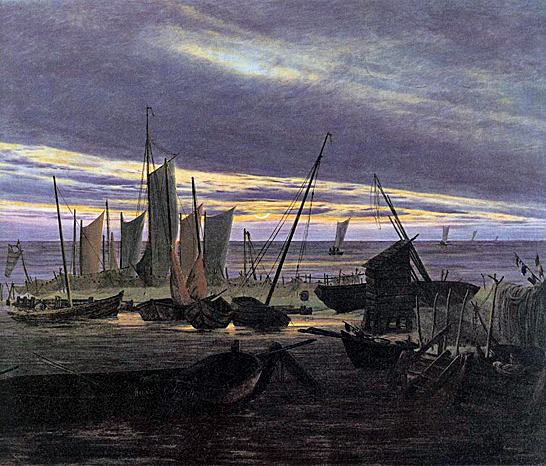

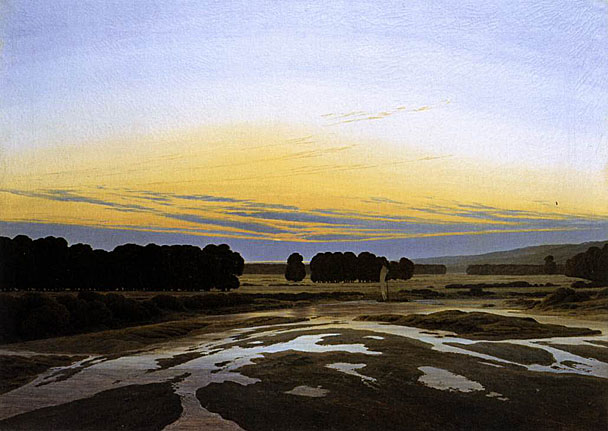

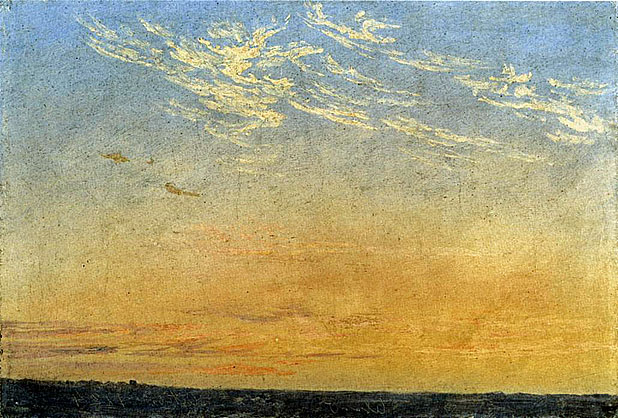

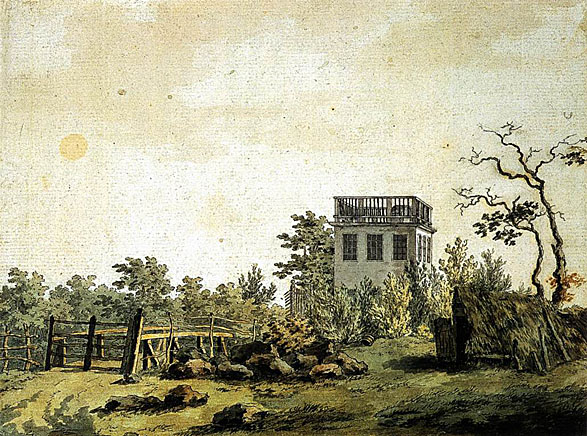

In 1798 he settled permanently in Dresden. He often drew works, mainly naturalistic and topographical, with India ink, watercolor and sepia ink. It is unclear when he finally took up oil painting, but it was probably after the age of thirty. Landscapes were his preferred subject, inspired by frequent trips, beginning in 1801, to the Baltic coast, Bohemia, the Riesen Mountains and the Harz Mountains. Mostly based on the landscapes of northern Germany, his paintings depict woods, hills, harbors, morning mists and other light effects based on a close observation of nature. The paintings of this time were modeled on sketches and studies of scenic spots, like the cliffs on Rügen, and the surroundings of Dresden or Elbe. The studies themselves were made almost exclusively in pencil, and provided topographical information; the subtle atmospheric effects characteristic of Friedrich's maturity were rendered from memory. These effects would eventually be most concerned with the depiction of light, of the illumination of sun and moon on clouds and water, optical phenomena specific to the Baltic coast and that had never before been painted.

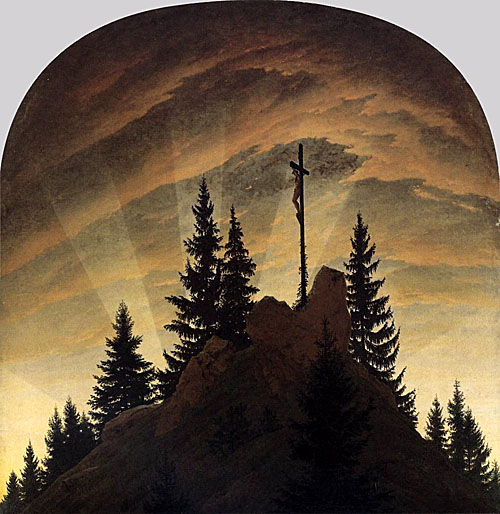

Friedrich's first major painting came at the age of 34. 'The Cross in the Mountains', now known as the 'The Tetschen Altar' (Gemäldegalerie, Dresden), was an altarpiece panel exhibited in 1808. The work met with controversy, but it was his first painting to gain wide appraisal; for the first time in Christian art, a pure landscape was the panel of an altarpiece. It depicts the crucified Christ in profile at the top of a mountain, alone, surrounded by nature. The cross rises highest in the composition, but is viewed obliquely and at a distance. The mountain symbolizes an immovable faith, while the fir trees represent hope. The artist and critic Basilius von Ramdohr published a lengthy article rejecting Friedrich's use of landscape in such a context; he wrote that it would be "a veritable presumption, if landscape painting were to sneak into the church and creep onto the altar". Rahmdohr was fundamentally asking whether a pure landscape painting could convey an explicit meaning.

_1808.jpg)

The 34-year-old painter was inordinately proud of the work. It was the largest he had painted so far, in a medium in which he was still far from proficient, and he had designed the frame himself - a Gothic arch with the eye of God and the wheat and vine of the Eucharist. He had intended the picture as a gift to the Swedish king Adolphus IV, in recognition of his resistance to Napoleon, but was persuaded instead to sell it to Count von Thun-Hohenstein for his castle in Tetschen, Bohemia. With its splendid frame it was transformed from political gesture to religious image, but still it remained a landscape. Nature itself was imbued with religious feeling.

Friedrich's friends publicly defended him, and the artist wrote a programme providing his interpretation of the picture. In his 1809 commentary on the painting, Friedrich compared the rays of the evening sun to the light of the Holy Father. That the sun is sinking suggests that the time when God reveals himself directly to man is past. Friedrich's extended interpretation of his own work was the first and last of its kind.

His recognition as an artist began with an 1805 prize at a Weimar competition. In 1810, Friedrich was elected a member of the Berlin Academy after the purchase of two of his paintings by the Prussian Crown Prince. Six years later he was elected a member of the Dresden Academy, a position which carried an annual stipend of 150 thalers.

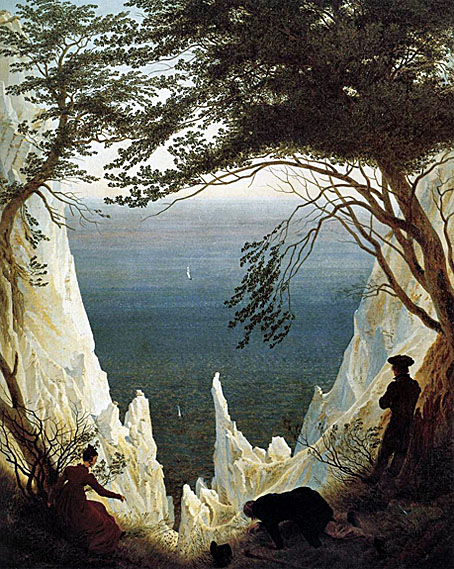

On 21 January 1818, Friedrich, then 44, married Caroline Bommer. Bommer was twenty-five years old, the daughter of a dyer from Dresden, and a gentle, unassuming woman. The couple had three children, with their first, Emma, arriving in 1820. Carus noted that marriage did not change Friedrich's life or personality, yet his canvasses from this period have new levity. Female figures appear in his work, his palette is brighter, and the dominating symmetry and austerity are lessened. 'Chalk Cliffs on Rügen', painted after his honeymoon, is a good example of this development.

With this daring construction Friedrich has succeeded in making a visual combination of two extremes: the plunging ravine with its view of the sea and at the same time the endless horizon.

_1818_20.jpg)

Caroline was probably the model for the female figure in old-German dress. Since she is stepping towards the light like an early Christian in prayer, some have sought to interpret the painting in terms of a communion with nature. On the other hand, the atmosphere evoked in Friedrich's painting might be interpreted as that of dusk, the path which terminates so abruptly as an announcement of death, and the boulders scattered alongside the path as symbols of faith. In the final analysis, few of Friedrich's pictures are as emphatic and almost exaggeratedly symbolic in their effect - factors which render the painting not unproblematic for the viewer.

The artist found support from two sources in Russia. The Grand Duke Nikolai Pavlovich visited Friedrich's studio in 1820, returning to Saint Petersburg with paintings for his wife Alexandra Feodorovna. The poet Vasily Zhukovsky, tutor of heir to the throne Alexander II, met Friedrich in 1821 and found in him a kindred spirit. Over many years Zhukovsky helped Friedrich by purchasing his work and recommending his art to the royal family, especially at the end of Friedrich's career, by which time he was poor. Zhukovsky said that his friend's paintings "please us by their precision, each of them awakening a memory in our mind."

Friedrich was acquainted with Philipp Otto Runge, another leading German painter of the Romantic period, and gained the admiration of the poet Goethe. He was also a friend of Georg Friedrich Kersting, who painted him at work in his unadorned studio, and the Norwegian painter Johann Christian Dahl. Dahl was close to Friedrich during the artist's last years, and complained that to the art-buying public, Friedrich's pictures were only "curiosities". While the poet Zhukovsky appreciated Friedrich's psychological themes, Dahl attended to the descriptive quality of Friedrich's landscapes. Dahl said, "Artists and connoisseurs saw in Friedrich's art only a kind of mystic, because they themselves were only looking out for the mystic … They did not see Friedrich's faithful and conscientious study of nature in everything he represented".

In June 1835, Friedrich suffered a stroke that caused some limb paralysis. He took a rest cure at Teplitz, but his ability to paint was greatly diminished. He worked only in watercolor and sepia, and symbols of death appeared heavily in his work, such as a sepia with an outsized owl perched on a grave in front of a full moon. By 1838, he was almost incapable of artistic work, lived in poverty, and was increasingly dependent on the charity of friends. His work was now considered anachronistic, and his death in May 1840 caused little stir in the artistic community.

One of Friedrich's key innovations is his original use of the landscape genre to evoke religious themes. In his time, most of his best-known paintings were viewed as expressions of a religious mysticism. His landscapes seek not just the blissful enjoyment of a beautiful view, as in the Classic conception, but rather an instant of sublimity, a reunion with the spiritual self through the lonely contemplation of an overwhelming Nature. Friedrich said, "The artist should paint not only what he sees before him, but also what he sees within him. If, however, he sees nothing within him, then he should also refrain from painting that which he sees before him. Otherwise, his pictures will be like those folding screens behind which one expects to find only the sick or the dead."

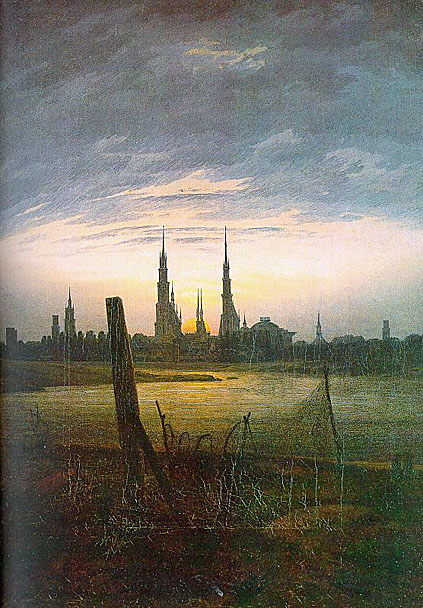

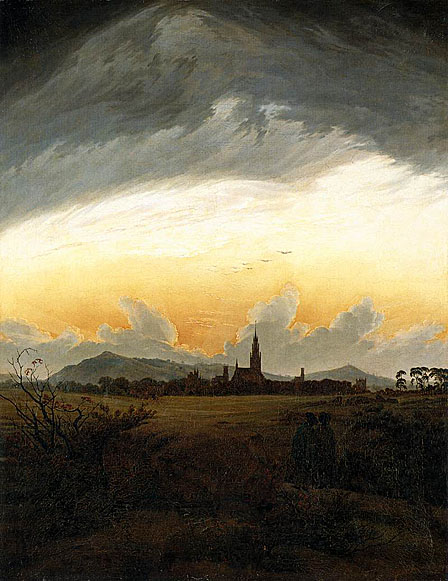

Expansive skies, storms, mist, forests, ruins, and crosses bearing witness to the presence of God are frequent elements in Friedrich's landscapes. Symbols of death occur in boats that move away from shore, a Charon motif, and in the poplar tree. Death is referenced more directly in paintings like 'The Abbey in the Oakwood', in which monks carry a coffin past an open grave, toward a cross, through the portal of a church in ruins.

'The Abbey in the Oakwood' is an expression of grief at the loss of a great past. The artist has chosen to depict an architectural ruin; it may testify to the sublimity of the past, but it is a monument in a graveyard.

The Napoleonic invasion of Germany and the consequent War of Liberation had added a patriotic dimension to Friedrich's subjects of north German ecclesiastical buildings in ruins or, in imagination, raised again. While the essential message of the 'Abbey in the Oak-wood' of 1810 is the passing of the earthly life, its fog-bound ruin and blasted, leafless trees inevitably evoked the contemporary state of Germany.

The painting was exhibited with its companion picture, the 'Monk by the Sea'. This suggests the hope of resurrection in its bright sky, in contrast to the dark clouds that loom above the figure on his Baltic shore.

The official recognition, indicated by the royal purchase, came as a surprise, for the canvas had initially been met with bemusement, even from Marie von Kügelgen who had earlier admired his work. When she saw it in 1809, Marie described it to her friend Friederike Volkmann:

"A vast endless expanse of sky ... still, no wind, no moon, no storm - indeed a storm would have been some consolation for then one would at least see life and movement somewhere. On the unending sea there is no boat, no ship, not even a sea monster, and in the sand not even a blade of grass, only a few gulls float in the air and make the loneliness even more desolate and horrible."

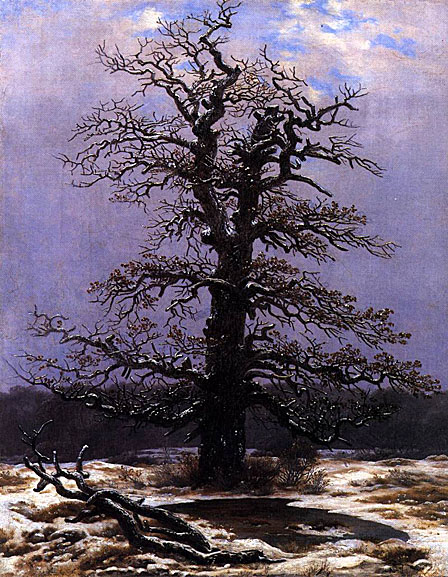

The bare oak trees are a recurring element of Friedrich's paintings, symbolizing the "pagan aspect" of death. Countering the sense of despair are Friedrich's symbols for redemption: the cross and the clearing sky promise eternal life, and the slender moon suggests hope and the growing closeness of Christ. In his paintings of the sea, anchors often appear on the shore, also indicating a spiritual hope. Writing in Studies in Romanticism, Alice Kuzniar finds in Friedrich's painting a temporality-an evocation of the passage of time-that is rarely granted the visual arts. In 'The Abbey in the Oakwood', then, the movement of the monks away from the open grave and toward the cross and the horizon imparts Friedrich's message that the final destination of man's life lies beyond the grave.

With dawns and dusks constituting prominent themes of his landscapes, Friedrich's own later years were characterized by a growing pessimism. This is reflected in his work, which becomes darker, showing a fearsome monumentalism. 'The Wreck of Hope', also known as 'The Polar Sea' or 'Sea of Ice', perhaps summarizes Friedrich's ideas and aims at this point, though in such a radical way that the painting was not well received. Painted in 1824, it depicted a grim subject, a shipwreck in the Arctic Ocean. That same year Friedrich was appointed professor at the Academy in Dresden. Between 1830 and 1835 he became more reclusive, and he dismissed the opinions of critics and the public by only painting for his family and friends-yet his art from this period can be considered among his finest. His well-known and especially Romantic painting 'Wanderer above the Sea of Fog' impressed Karl Friedrich Schinkel (later Prussia's most famous classicist architect) so much that he gave up painting and took up architecture.

In the painting, now often called 'The Wreck of the Hope', the painter imbued the subject with unsurpassable dramatic intensity. The particular feature of this work is that the drama has already happened. The huge towering pinnacles are the slowly moving icebergs that have long become fixed here. The bold attempt by man to burst the bounds of his allotted sphere ends in death.

When the artist was 13, an accident occurred, that, perhaps subconsciously, formed part of the shadow that seemed to darken his temperament throughout his life. While ice skating he was saved from drowning by his younger brother Christoph, but Christoph himself drowned in the icy water before his eyes. It can be hardly denied that Friedrich's various "sea of ice" paintings must be seen in relation to this traumatic experience.

Friedrich's figures that habitually turn their backs to gaze into the horizon or stare from windows with rapt attention are images of the artist. His Wanderer, frock-coated and stick in hand, has climbed to a rocky peak above swirling mountain mists; the viewer looks with his eyes, the angle of vision being exactly aligned to their level in the picture space. The foreground, the conventional plateau to give the viewer a fix on the subject, has been entirely dispensed with.

Friedrich's written commentary on aesthetics was limited to a collection of aphorisms written in 1830, in which he explains the need for the artist to match natural observation with an introspective scrutiny of his own personality. His best-known remark advises the artist to "close your bodily eye so that you may see your picture first with the spiritual eye. Then bring to the light of day that which you have seen in the darkness so that it may react upon others from the outside inwards." Eschewing overreaching portrayals of nature in its "totality", as found in the work of contemporary painters like Ludwig Richter and Joseph Anton Koch, Friedrich observed:

What the newer landscape artists see in a circle of a hundred degrees in Nature they press together unmercifully into an angle of vision of only forty-five degrees. And furthermore, what is in Nature separated by large spaces, is compressed into a cramped space and overfills and overstates the eye, creating an unfavorable and disquieting effect on the viewer."

Underscoring Friedrich's patriotism during the French occupation of Pomerania, references to German folklore became increasingly prominent in his work. An anti-French nationalist, Friedrich also used the German landscape to celebrate the Germanic culture, customs, and mythology. He was impressed by the anti-Napoleonic poetry of Ernst Moritz Arndt and Theodor Körner, and the patriotic literature of Adam Müller and Heinrich von Kleist (Kleist was the first member of the Romantic movement to discuss Friedrich in print). Inspired by the deaths of three friends who had died in battle against France, and by Kleist's 1808 drama Die Hermannsschlacht, Friedrich undertook a number of paintings in which he intended to convey political symbols solely by means of the landscape-a first in the history of art. In Old Heroes' Graves, a dilapidated monument inscribed "Arminius" invokes the Germanic chieftain, a symbol of nationalism, while the four tombs of fallen heroes are slightly ajar, freeing their spirits for eternity. Two French soldiers appear as small figures before a cave, lower and deep in a grotto surrounded by rock, as if further from heaven. A second political painting, 'Fir Forest with the French Dragoon and the Raven' (ca 1813), depicts a lost French soldier dwarfed by a dense forest, while on a tree stump a raven is perched-a prophet of doom, symbolizing the anticipated defeat of France.

Friedrich sketched memorial monuments and sculptures for mausoleums, reflecting his obsession with death and the afterlife. Some of the funereal art in Dresden's cemeteries is his. Some of his paintings were lost in the fire that destroyed Munich's Glass Palace (1931) and in the bombing of Dresden in World War II.

Friedrich was almost forgotten in his homeland after his death in 1840. His artwork was not widely acknowledged during his lifetime, though it complied fully with the Romantic aesthetic of the time. While the close study of landscape and an emphasis on the spiritual elements of nature were commonplace in contemporary art, his work was too original and personal to be well understood. Only at the turn of the century was Friedrich rediscovered by the Norwegian art historian Andreas Aubert, and by the Symbolist painters, who valued his visionary and allegorical landscapes. It was this aspect of his work that caused Max Ernst and other Surrealists to see him as a precursor to their movement. Exhibitions in London in 1972 and Hamburg in 1974 produced international recognition.

French sculptor David D'Angers, who visited Friedrich in 1834, was moved by the devotional issues explored in the artist's canvasses. He exclaimed to Carl Gustav Carus in 1834, "Friedrich! … The only landscape painter so far to succeed in stirring up all the forces of my soul, the painter who has created a new genre: the tragedy of the landscape."

Alongside other Romantic painters Friedrich helped position landscape painting as major genre within Western art. Friedrich's style influenced the painting of Dahl, but whether the successors to his painting style achieved his mastery and depth is debated. Arnold Böcklin was strongly influenced by his work, and perhaps as well the painters of the American Hudson River School, the Rocky Mountain School, the New England Luminists and American painters like Albert Pinkham Ryder and Ralph Blakelock. He has been advocated by artists such as David Hockney, and is represented in many major international collections, although most of his work remains in Germany.

Precisely when Friedrich first experimented in oils remains the subject of dispute. Even if we attribute to him the 'Wreck in the Sea of Ice' this must remain an isolated tentative attempt, since sepia drawings subsequently continue to dominate his output.

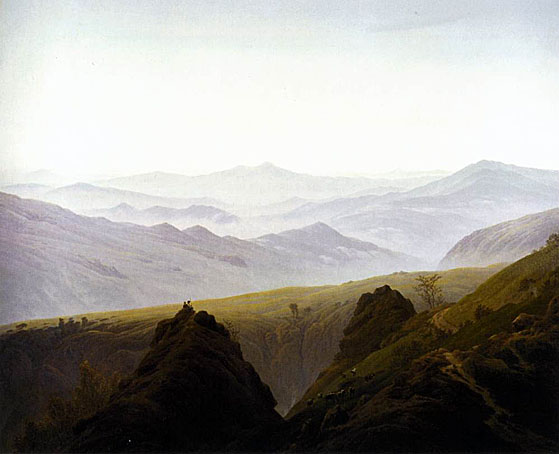

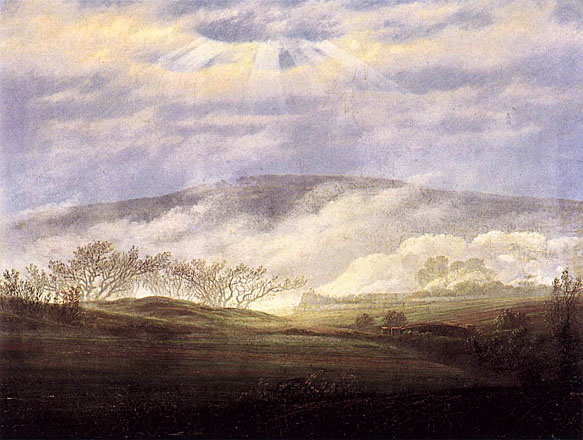

This painting conveys Friedrich's impressions of the countryside in the Bohemian mountains south of Teplitz. Our gaze is taken to the right to Mount Milleschauer, and then, because of the painting's symmetrical structure, to the equally sweeping profile of a second mountain, the Kletschen, to the left. The eye returns from the bluish-green silhouette of these distant mountains to the luscious green sloping pastures at the front. From there it travels down the path to the low-built house in the valley lying, half-concealed, amidst the trees and bushes; the presence of human life is revealed by the column of smoke rising from its chimney. Or we may climb in our minds up the hill to the right of the house, which becomes an increasingly pale yellowish-green with height, perhaps to gain an even better perspective of the landscape. The ease with which the beginning of this path in the foreground takes us on a tour of the scene seems to correspond with the tranquil state of mind brought about by the painting, and accords perfectly with its depiction of nature. With its wonderful delicacy and its relaxed, serene mood, the painting must be one of the most beautiful landscapes in German art.

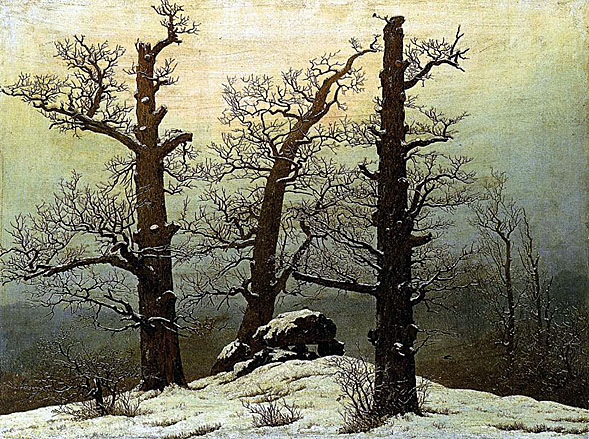

Friedrich was not the only one of his countrymen in this period to draw an analogy between 'native German' Gothic church architecture and the natural growth of forest trees, and the imagery here almost certainly reflects his sympathies with the patriotic and democratic movements of the day as well as his religious faith.

'Winter Landscape' was painted with surprisingly few pigments, suggesting that Friedrich was less interested in color than in smoothly graduated tones. He achieved the striking effect of shimmering, transparent haze by careful stippling with the point of the brush, using a blue pigment - smalt - which is transparent in an oil medium.

In the decades before and around 1848 the world, and especially the artists of the time, looked from the north to musical Vienna, and listened to the music of the classical Viennese period. The crow on a dead branch, or the painting of the lonely wanderer between bare trees in Friedrich's Winter Landscape, was set to music by Schubert in his Winterreise.

The Schwerin painting is characterized by the somberness of an expanse of snow stretching away into the infinite distance, which modern interpreters see as a symbol of death, a nihilistic sign of doom. The pendant in Dortmund introduces, for the first time in Friedrich's oeuvre, a Gothic church, seen as a monumental vision emerging out of the mist like a phantasmagoria and rising against the gloomy background of a winter sky. Nearer the viewer, a man is leaning back against a boulder and gazing up the crucifix in front of a cluster of young fir trees. He has flung his crutches demonstratively far away from him into the snow. This combination of motifs has been interpreted as a reference to the security of the Christian in his faith.

_ca_1835.jpg)

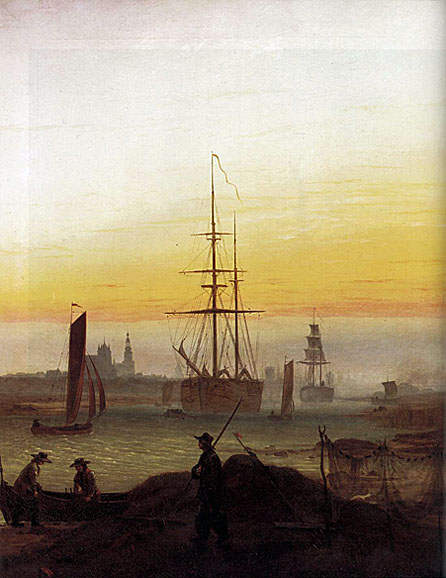

As if we ourselves were on board, our eyes are directed towards the prow of the boat, where a couple is sitting. They are holding hands and gazing at the distant city ahead, its church spires and buildings emerging hazily from the mist. The woman is Caroline, the artist's wife, and the man is probably intended to be Friedrich. The artist is possibly referring here to the motif of the ship of life, to the notion of life as a journey from this world to the next, as familiar from Christian pictorial and literary tradition. The picture is dominated, however, by the emotional span between the narrowness of the boat, the way in which it seems to be gliding soundlessly forwards, strangely without waves, and the longed-for horizon. Dominant, too, is the bold composition with its slightly offset verticals (the mast), its horizontals (the distant shore) and its foreshortened view of the wedge-like front of the ship. It would be several decades before a close-up view of this kind would be encountered again in the work of the Impressionists.

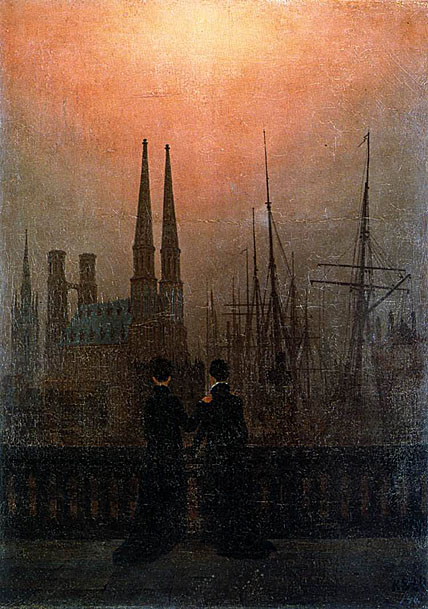

In this ethereal painting, human and natural symbolism is subtly interwoven. The moon, an old Christian sign of hope, gleams from behind a withered tree, watched by two men, perhaps the artist and a pupil, in the 'old German' costume favored by the resistance movement during the years of Napoleonic occupation. Painted after this threat had lifted, the picture links past, present and future through the cycles of time and season and the intercession of their human observers.

In response to demand from his clientele, Friedrich executed several copies of this composition, a number of which remain in private collection. He took up the motif again, in slightly varied form, in the painting 'Man and Woman Contemplating the Moon' (ca 1824, Nationalgalerie, Berlin), in which he has perhaps portrayed himself and his wife in this scene of Romantic wonderment.

_1825_30.jpg)

Despite its apparent fidelity to nature, the painting reveals a somewhat fantastical element in its mixture of different geological formations and its unnatural ratios of scale.

Oak trees run like a leitmotif throughout Friedrich's oeuvre, often in conjunction with a dolmen. They are a reminder of the artist's personal roots and are at the same time charged with nationalist sentiment.

The oak is a symbol of the pre-Christian world. The fallen branches denote the meaningless of heathen existence, while signs of spring in the melting snow and the blue sky herald new life in Christ.

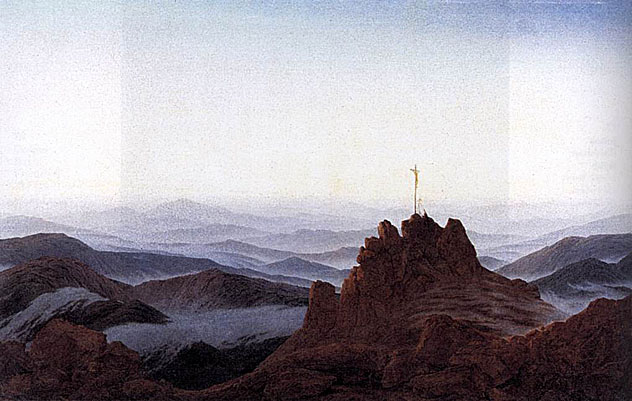

With his friend Kersting he had made a tour of the mountainous area near Dresden known as 'Saxon Switzerland', in the summer of 1810. 'Morning in the Riesengebirge', painted shortly afterwards, is another exposition of his theme of the cross on a peak. In this later picture of the early 1830's, Friedrich recollected his mountain tour in terms of pure landscape, with only a shepherd to inhabit it; the zones of earth and heaven are harmonized by the melding vapor of morning mist.

With the richness of its palette, the beauty of its composition and its sonorous atmosphere, this impressive painting is a true masterpiece in the history of European landscape painting.

_1830-35.jpg)

Source: Art Renewal Center

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.