1860 - 1939

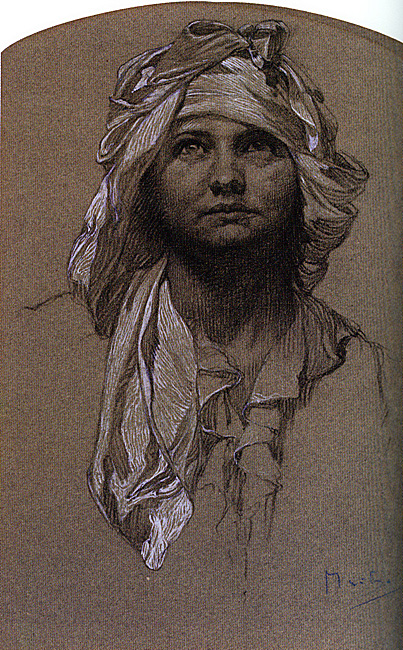

Alfons Maria Mucha was born in the town of Ivancice, Moravia. His singing abilities allowed him to continue his education through high school in the Moravian capital of Brno, even though drawing had been his first love since childhood. He worked at decorative painting jobs in Moravia, mostly painting theatrical scenery, then in 1879 moved to Vienna to work for a leading Viennese theatrical design company, while informally furthering his artistic education. When a fire destroyed his employer's business in 1881 he returned to Moravia, doing freelance decorative and portrait painting. Count Karl Khuen of Mikulov hired Mucha to decorate Hrusovany Emmahof Castle with murals, and was impressed enough that he agreed to sponsor Mucha's formal training at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts.

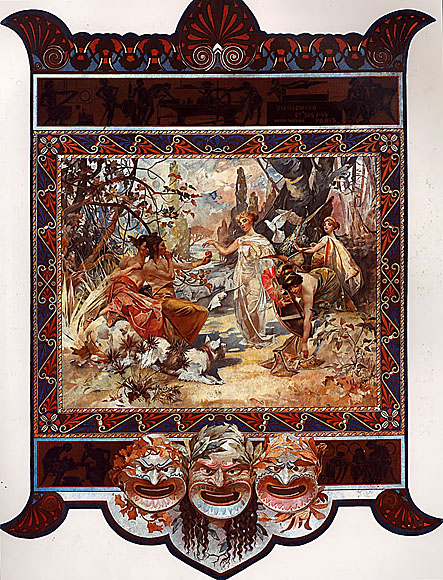

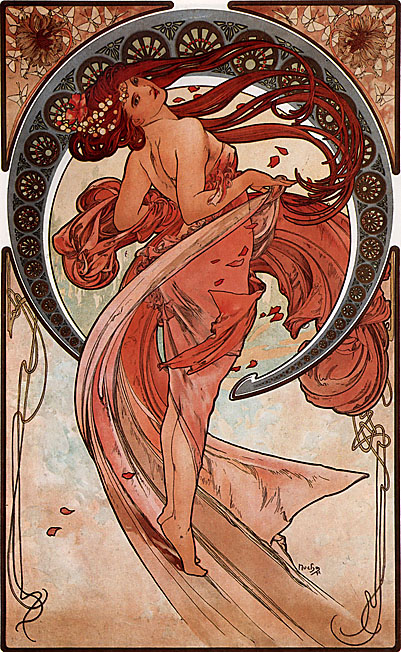

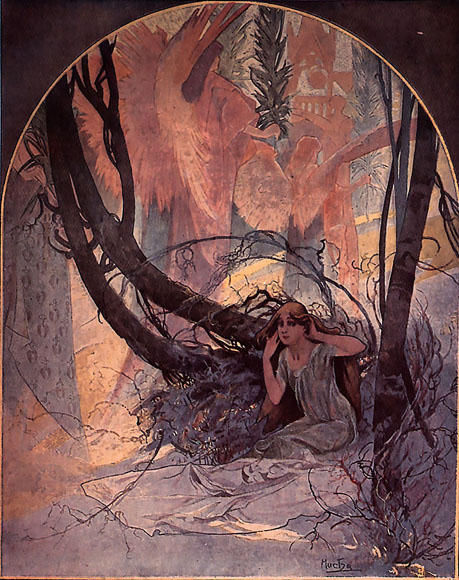

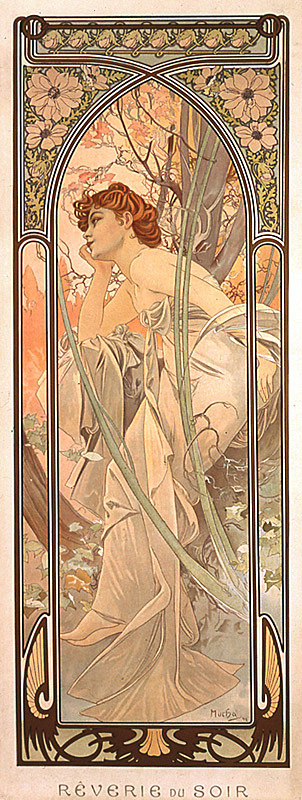

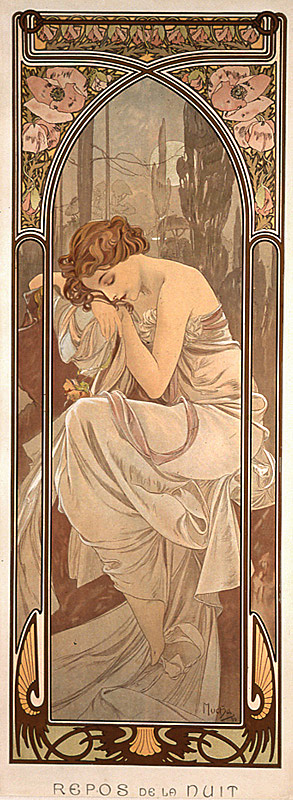

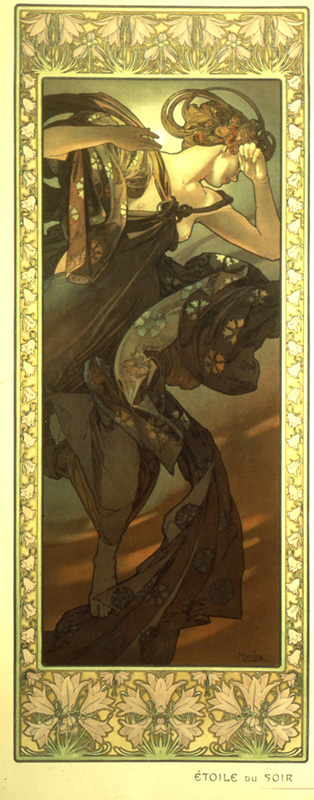

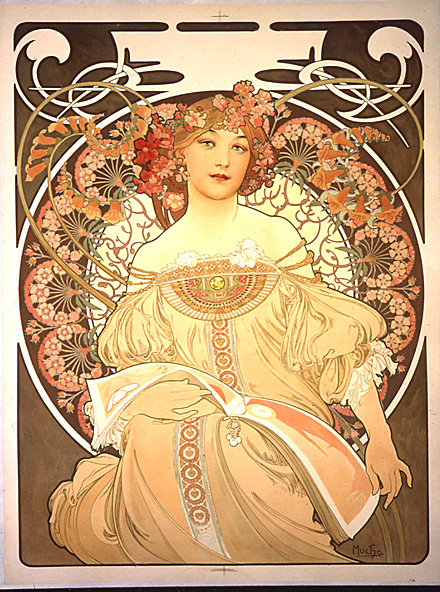

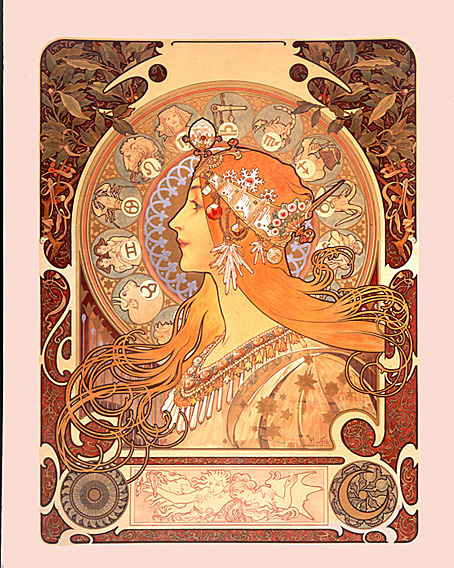

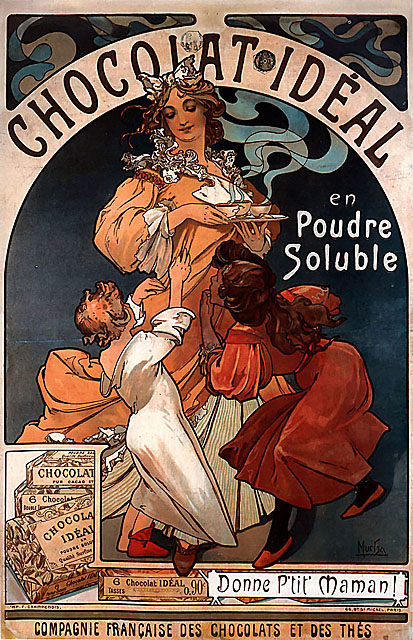

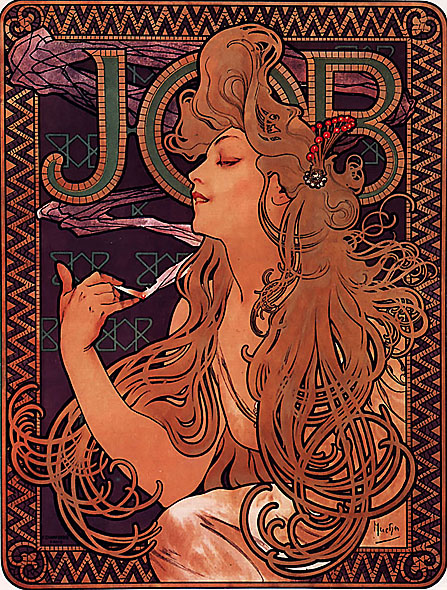

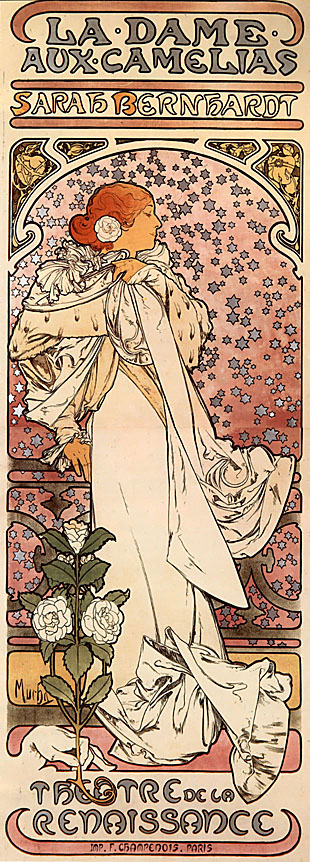

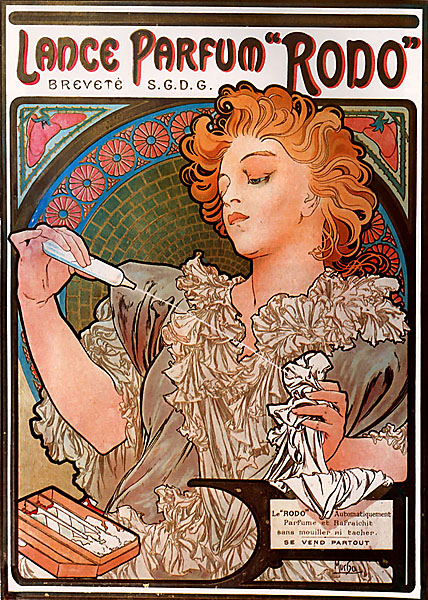

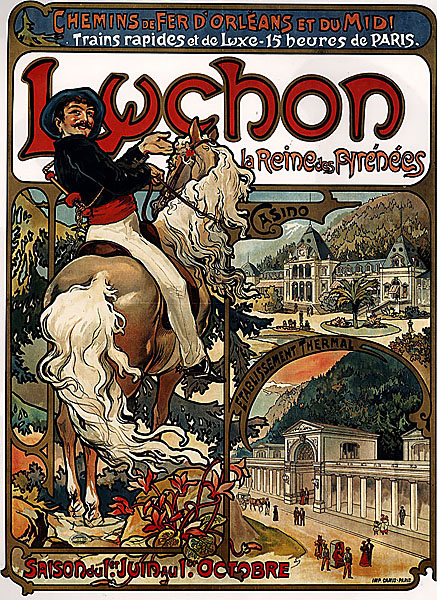

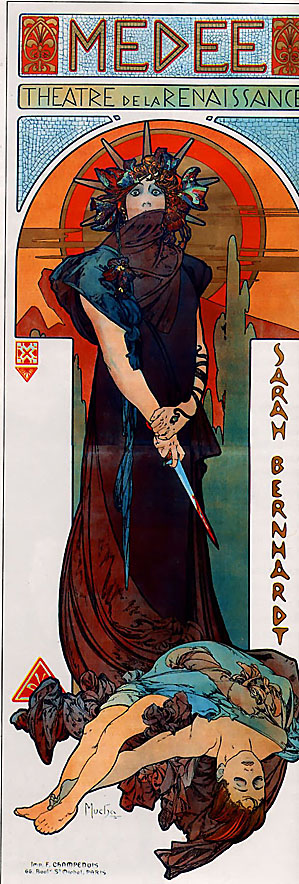

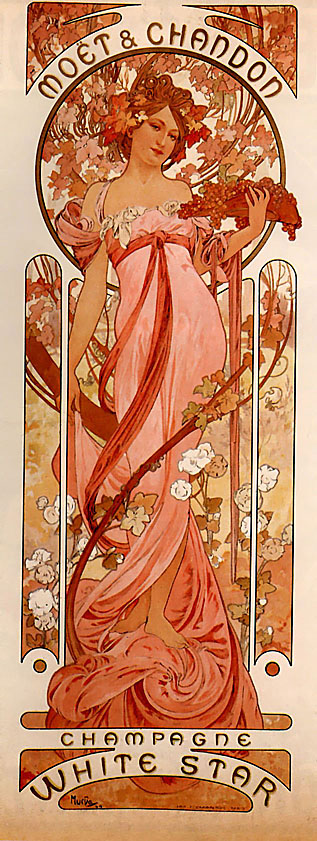

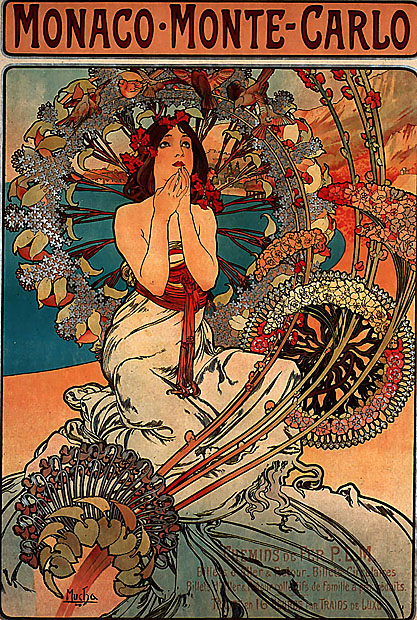

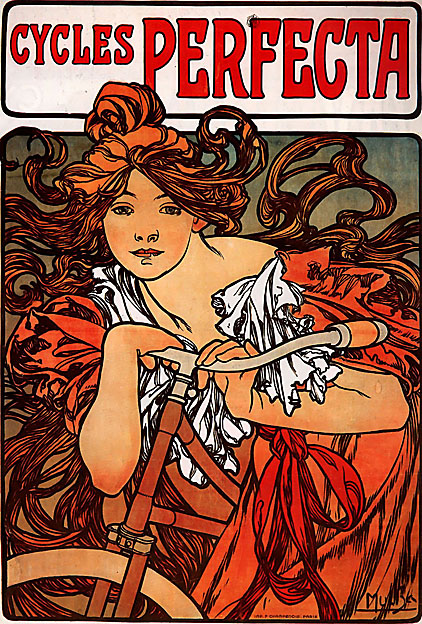

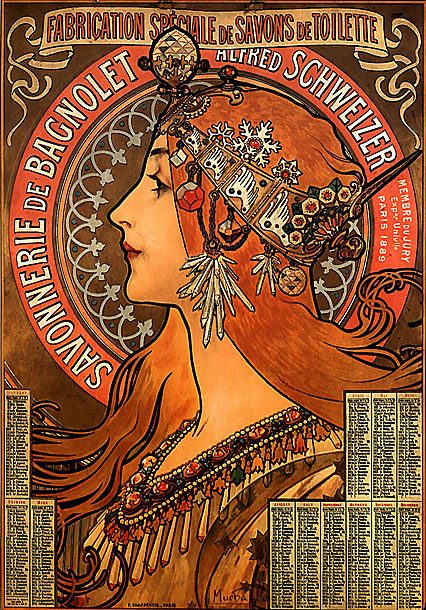

Mucha produced a flurry of paintings, posters, advertisements, and book illustrations, as well as designs for jewelry, carpets, wallpaper, and theatre sets in what came to be known as the Art Nouveau style. Mucha's works frequently featured beautiful healthy young women in flowing vaguely Neoclassical looking robes, often surrounded by lush flowers which sometimes formed haloes behind the women's heads. His art nouveau style was often imitated.

Mucha married Maruska (Marie/Maria) Chytilova on June 10, 1906, in Prague. The couple visited the U.S. from 1906 to 1910, when their daughter, Jaroslava, was born in New York City. The family then returned to the Czech lands and settled in Prague, where he decorated the Theater of Fine Arts, contributed the murals in the Mayor's Office at the Municipal House, and other landmarks of the city. When Czechoslovakia won its independence after World War I, Mucha designed the new postage stamps, banknotes, and other government documents for the new state.

The rising tide of fascism in the late 1930s led to Mucha's works, as well as his Slavic nationalism, being denounced in the press as 'reactionary'. When German troops marched into Czechoslovakia in the spring of 1939, Mucha was among the first people to be arrested by the Gestapo. During the course of the interrogation the aging artist fell ill with pneumonia. Though eventually released, he never recovered from the strain of this event, or seeing his home invaded and overcome. He died in Prague on July 14 of a lung infection, and was interred there in the Vysehrad cemetery.

The first painting of the series presents a Slavic Adam and Eve in hiding from an invasion force sometime during the third to sixth centuries. The white of their clothing represents purity and innocence and contrasts with the flames of a village set ablaze by the soldiers. Most interesting is the levitating figure on the right; he is a pagan priest praying for mercy for his suffering people. Under his his left arm is a girl wearing a green wreath as a symbol of peace and under his right is a warrior youth representing the just war. The message conveyed is that, in future, the Slavic people must fight for their freedom.

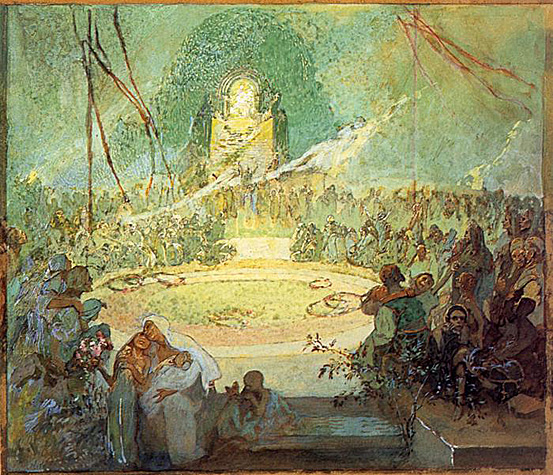

This image depicts the celebration of the harvest festival of honoring the pagan god Svantovit, taking place on the Baltic island of Rujana's capital city of Arkona. The treasure-filled temple which lay at the heart of the celebration was a place of pilgrimage for Slavs during the eighth to tenth centuries. Arkona was later conquered by Danish warriors and, by Mucha's time, had acquired mythic status as a symbol of former Slavic glory.

The temple can be seen in the left background. Brightest amongst the pilgrims in the foreground is a mother and child, with sun setting on the scene behind her. In the top left is the Viking god Thor with a pack of dogs, foretelling the future destruction of Arkona. At the very top, centre, a Slavic warrior is dying in the in front the figure of Svantovit who sprouts the leaves of the linden tree. The vertical shaft of blue/white is the warrior's sword which is being taken by the god to protect the future of the Slavs. The importance of artistic endeavor as a response to war is emphasized by the three musicians in the centre right of the composition and the foreground figure of a wood carver being consoled and inspired by his muse.

In the late ninth century, the Moravian Ruler, Prince Rostislav of Moravia recruited two Greek monks, Cyril and Methodius to translate parts of the Bible and the liturgy in Slavonic, a move opposed by the German bishops but sanctioned by Rome.

The picture shows a Papal Bull being read to Rostislav's successor Svantopluk in front of Velehrad, the fortress and capital of Moravia. Methodius, now archbishop, is the aged, tall figure in the centre bathed in light and supported by acolytes while the guards to the left, covered in shadow, introduce a note of menace.

Upper left is a group of distressed Slav women being comforted by Cyril and at the centre of the upper level are Rostislav and the Patriarch of the Eastern church. The group of four figures upper right are the Bulgarian and Russian rulers, Boris and Igor, who supported Slavic liturgy. The figure at the front is an earnest youth holding a circle, a symbol of Slavic unity. Cyril and Methodius remain popular Moravian Saints and this work celebrates their achievement.

The period of Slavic liturgy came to an end with the death of Methodius and his disciples were forced to take refuge in the court of the Bulgarian Tsar Simeon. A former monk who became an important military figure, Simeon was also a considerable scholar who commissioned the translation of many Byzantine texts into Slavonic.

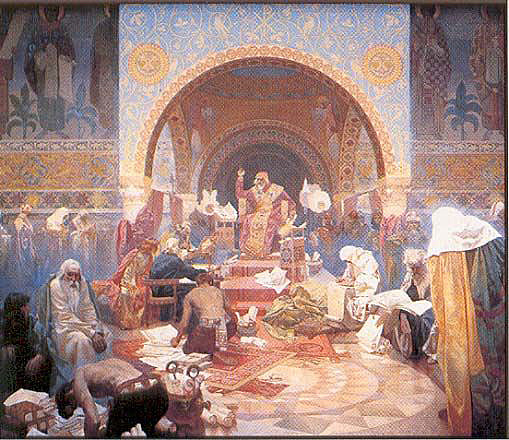

The Tsar is shown in a magnificent Basilica, with the expelled priests being depicted in the upper mosaics. The Tsar is in every sense central to the composition, radiating authority and grandeur; he is attended by philosophers, writers, linguists and scribes all intent on their work. The subject matter of their attention is the books and documents encapsulating the past and future of the Slavic people.

The period of Slavic liturgy came to an end with the death of Methodius and his disciples were forced to take refuge in the court of the Bulgarian Tsar Simeon. A former monk who became an important military figure, Simeon was also a considerable scholar who commissioned the translation of many Byzantine texts into Slavonic.

The Tsar is shown in a magnificent Basilica, with the expelled priests being depicted in the upper mosaics. The Tsar is in every sense central to the composition, radiating authority and grandeur; he is attended by philosophers, writers, linguists and scribes all intent on their work. The subject matter of their attention is the books and documents encapsulating the past and future of the Slavic people.

Premysl Otakar II who ruled from 1253 to 1278, was one of the greatest kings in Czech history, famed for his military successes, wealth generosity and political acumen. The mural depicts the wedding celebration of one of his nieces, to which he invited all Slavic rulers in an attempt to forge an alliance and bring about peace.

The setting is a large tent with a enclosed chapel showing the King's crest, a spread eagle. Otakar himself, is greeting two of his guests while others inanimately observe.

Stepan Dusan was a strong military leader who took advantage of the failing Byzantine empire to expand Slavic territory southwards, being crowned in 1346 as Tsar of the Serbs and Greeks. From this position he instituted a code of law which held force throughout the Roman Empire.

The subject of the picture is the procession which followed the coronation. It is led by young girls in native dress who steal the scene from the elders bearing the Tsar's sword and crown, their youth expressing Mucha's hope for the future. The newly crowned Tsar's red-lined cloak frames his figure in the center of the composition.

Milic was a Fourteenth Century figure from Moravian who was critical of the excesses of the established church and whose devotion to the poor of Prague earned him a large following. He converted many prostitutes and in 1372 built a convent dedicated to Mary Magdalene on the site of a brothel.

The figures on top of the scaffolding are planning the nunnery which will care for the poor. Underneath, Milic is an unassuming figure on the right preaching to a group of women who are swapping their finery for the white robes of nuns, the purity of which is emphasized by the snow on the ground. The mural is a tribute to the power of faith and compassion.

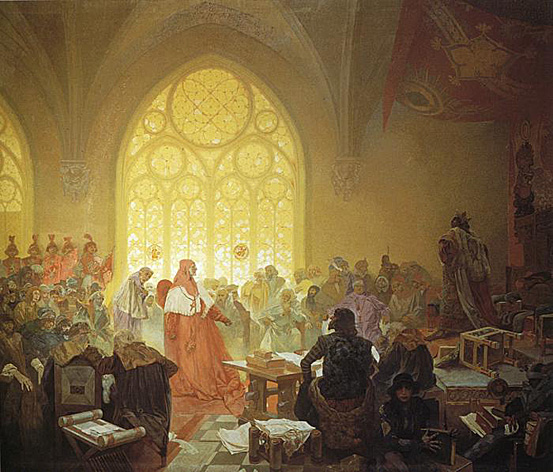

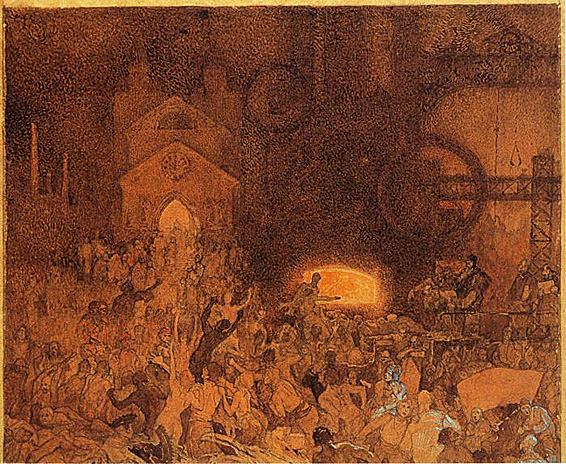

In the Fifteenth Century, Jan Huss emerged as a religious leader in Prague and was to become the major figure of the Reformation in Bohemia. He was burned at the Stake in 1414 following an appearance at the Council of Constance, an incident which triggered a Czech national rebellion which led in turn to the Hussite wars.

Mucha shows Huss preaching in the Bethlehem chapel in Prague in 1412, with attending students taking notes. On the right of Huss is the founder of the chapel, merchant Kriz, while to his left is Jan Zizka, future military leader of the Hussites; Queen Sophia is seated under the baldachin on the right. A priest by the baptismal font, extreme left, is making notes for use in the trial of Huss at the Council of Constance.

Following the death of Jan Huss, the leadership of the Slavic religious reform movement passed to the Utraquist preacher Koranda, who supported the controversial practice of taking communion sub utraque (under both kinds), that is in the form of both bread and wine. Here he is shown preaching to a gathering crown at Krisky on 30 September 1419, when he advised his followers that weapons as well as faith would be needed. This was the start of the Hussite Wars, as foretold by the dark skies. The white and red flags are symbols of life and death.

The early fourteenth century was marked by military incursions by the German Order of Teutonic Knights into the land of the Northern Slavs. In response, The Polish King Wladyslaw Jagiello and the Czech King Vaclav IV signed a defensive treaty which was first acted upon at the battle of Grunwaldu in 1410 when the Slavs won an important victory. Mucha elects to illustrate not the fighting but the aftermath, with the Polish King holding his face in sorrow as he views the cost to both enemy and ally.

In 1420, in the early stages of the Hussite wars, the German King occupied the castle at Prague and was crowned king. A peasant army of Hus's followers arrived from Southern Bohemia to oppose the Germans, led by a brilliant military leader, Jan Zizka of Troenov. Their position at the hill of Vitkov was under siege until relieved by a group of Czech soldiers from Prague arrived, led by a priest bearing a monstrance. The mural shows the priest at a field bearing the monstrance and surrounded by supplicating clergy, with Prague's Hradcany Castle visible to the right. The sun has broken through the dark shy and is shining on the figure of Zizka, a sign of God's grace that had ensured military victory. The woman with children, front left, undercuts the triumphal atmosphere by turning her back on the celebration, knowing perhaps that the war will claim the lives of her sons.

This composition though stylistically similar to the depiction of the battle of Vitkov, deals with a different aspect of the Hussite Wars. Vodnany was a small town caught in the crossfire between the Hussites and the Germanic forces. They chose to flee to Petr Chelcicky, a religious peasant philosopher. When they arrived, they lay down exhausted and dying, consumed by anger and grief, their homes burning in the background. Chelcicky moves amongst them with a Bible, offering comfort and support, asking that they do not seek vengeance.

This is the most clearly pacifist of Mucha's series of battle paintings and relates closely to the carnage brought about by the First World War which was drawing to a close when the scene was painted.

In the 1430's Rome was forced to accept the Hussite demands and end their Crusades into Slavic territory. When the Czech elected the native born Juri of Podebrandy in 1458, the opportunity to entrench their independence arose. He visited Rome in 1462 to obtain Papal approval to his election but was rebuffed and returned to Prague in the company of Cardinal Fantin who was explain the position to the Czechs. The mural shows the Cardinal in the meeting Hall of the Royal Apartments in the Old Town of Prague, demanding that the King submits to Rome's authority. The King was to reply that 'On this earth I do not accept anyone as a judge of my conscience'. The boy at the front has closed a book which bears the title 'Roma finita', a development which means, to Mucha, the birth of new religious light and freedom symbolized by the sun pouring in through the Gothic window.

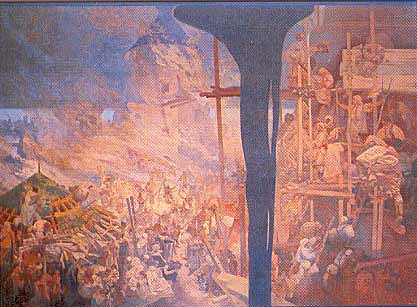

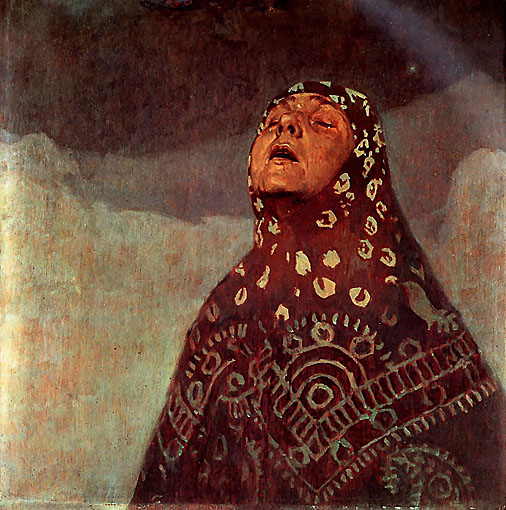

In 1566 The Turks began advancing along the Danube into the Hungarian plains. Their advance was eventually halted at the city of Sziget by a citizens' army let by Croatian nobleman, Nicholas Zrinsky. With the town under siege, he was obliged to fire the Old Town to deter advances. After a further nineteen days and with Zrinsky dead, the women of the city took refuge a watchtower; Zrinsky's widow, realizing the inevitability of defeat, threw a touch into a gunpowder store, destroying the city but inflicting damage on the Turkish army which halted their progress.

Mucha captures the moment of the explosion in his only portrayal of an ongoing battle. In so doing, he divides the scene between the sharply focused sacrifice of the women on the right and the blurred images of destruction to the left. The device used to split the picture, a mushroom-shaped prop, is uncannily prophetic of later wars.

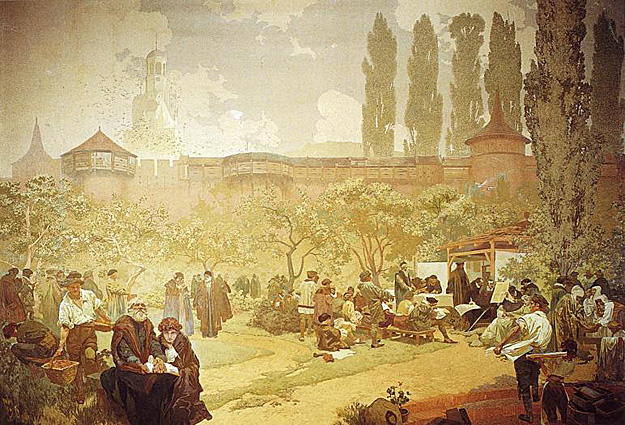

In the Sixteenth Century, the religious movement influenced by Petr Cheleocky known as the Bohemian Brethren, was forced to relocate from Bohemia and settled in Mucha's home town of Ivancise. From their new base they began to print the first complete version of the Bible in Czech, a project which was subsequently completed in Kralice, the town after which it became named. The Kralice Bible is still a major icon of Czech national identity. In this scene the nobleman who was housing the Brethren, Zerotina, inspects the first pages of the printed text as a number of students gather around the printing press on the right while to the left, a student is reading to a blind man.

The future is foretold by swallows circling the church tower before leaving from warmer climes - the Brethren too will soon be forced to move on. By the mid-eighteenth century they had populated many parts of Europe although their most famous settlements are Bethlehem in Pennsylvania and Salem in North Carolina.

Following military defeat in 1620, the Czechs were forcibly returned to Catholicism, with those who resisted being deported. Notable amongst the exiles was Jan Amos Komensky, a spiritual leader of the Brethren and a passionate advocate of education and learning. The spiritual content of his writings was a source of inspiration to his fellow countrymen who dreamed of a return to independence. Mucha depicts his death- scene, with Komensky inert in a chair on the sea shore of the Dutch town of Naarden where he lived in later life.

In the foreground are his followers mourning the death of their leader whose sense of loneliness and isolation is emphasized by the grays of the sea and the sky. The patch of light, centre left, comes from a small lantern which symbolizes the remote hope of return to the homeland.

This painting marks a break from the examination of key events of Slavic history, and pays tribute to the Greek Church which connected the Slavs to the Byzantine empire, particularly through the missionary activities of Cyril and Methodius. Mount Athos, depicted here, is the most sacred place in the Orthodox Church. On the right are a group of Russian pilgrims, knelling before the high priests whose ethereal appearance is attributable to the sunlight and foreground left is a blind old man being led by a youth.

Angels appear across the centre of the composition holding small models of four Slavic monasteries, while the two angels in the centre represent Charity and Faith. Overlooking the entire scene is an image of the Virgin Mary, reinforcing the link with the symbolic nature of the first three paintings in the series.

In the 1890's a patriotic youth organization called Omladina was formed, with a liberal, anti-clerical agenda. Their ideas met with official disapproval and their leaders were taken out of circulation in 1904. Mucha shows members of the movement taking a patriotic vow under the Linden tree occupied by a goddess and linking the movement with the mythic past of the Slavic people. The two standing figures on the left are painted in egg tempera, never having being finished in oils. Owing to this factor, the painting was never exhibited in Mucha's lifetime, leading some authorities to the harsh judgment that the entire cycle is 'unfinished'.

Also of interest are the figures on the low wall . Mucha used his own children as models for two of these figures; on the right the young boy is his son Jiri while to the left the figure playing a harp is his daughter Jaroslava. This later image is very similar to the one featured in the poster produced for the 1928 exhibition.

In Russia, serfdom was abolished by means of the Emancipation Edict of 1861, much later than elsewhere in Europe, The painting of the occasion shows a subdued crowd, uncertain as to what to make of the event, as perhaps expressed by the mother and child figure looking out from the left, her anxious expression reflecting the hard peasant life.

This sense of division between rulers and ruled is emphasized by the way in which St Basil's cathedral, the only central depiction of an extant building in the series, looms over the crowd with a somewhat threatening presence.

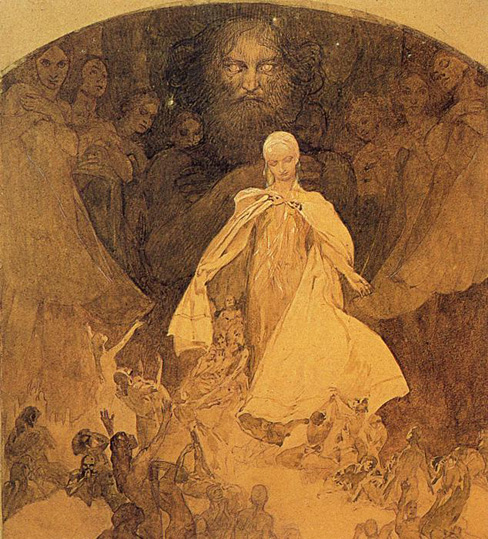

The final painting is designed to unify the entire series by presenting a vision of Slavic triumph as an exemplar for all of mankind. He uses four colors to deal with different aspects of Slavic history:

The blue in the bottom right represents the mythical early days.

The red in the upper left is indicative of the Hussite wars.

The black figures center right are the later enemies of the Slavs.

Bathed in yellow in the center are those who strove to bring about freedom, peace and unity.

The youths holding branches of the Linden tree are paying tribute to the Slavic heroes, included amongst them a small group of World War I soldiers, visible behind the branches. The main figure, the man with arms outstretched in the center stands for both the suffering of the Slavs down the ages and the hopes for the new republic. Other symbols include a circular wreath, standing for unity, the dove and the American flag as a gesture of gratitude for their part in the founding of the Republic of Czechoslovakia. A figure of Christ at the top blesses the entire scene.

In 1936 the Artist published his memoirs "Three Statements on My Life and Work".

Two years later, in 1938, Czechoslovakia was taken over by Nazi Germany, as a result of the Munich Agreement between the governments of Germany, Britain and France (Czechoslovakia was never invited to the negotiations). Since the suppression of nationalism was high on the agenda of the conquerors, Mucha, with his history of patriotism and Pan-Slavism, was arrested and incarcerated by the Gestapo.

Already an old man by this time, the painter caught pneumonia and died in prison on 14th July, 1939. His last work of art was the Slavs' Oath of Unity (1939).

Source: Art Renewal Center

Source: The Mucha Foundation

Source: The Slavic Epic

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.